6

CRAM, CRAM, CRAM

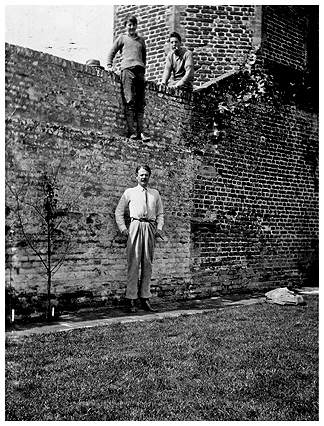

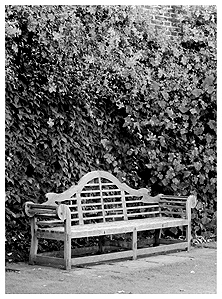

Harold, Nigel (left) and Ben after some of the first planting on the walls, August 1931.

In her planting, the filling and flowering up of her spaces, Vita had a clear and individual style. It is ‘Cram, cram, cram, every chink and cranny,’ she wrote on 15 May 1955. You have plants popping up in the paths: you have plants trained over almost every square inch of wall; and where there’s a gap, Vita encourages plants to grow in the walls. As she says of herself, ‘My liking for gardens to be lavish is an inherent part of my garden philosophy. I like generosity wherever I find it, whether in gardens or elsewhere. I hate to see things scrimp and scrubby. Even the smallest garden can be prodigal within its own limitations … Always exaggerate rather than stint. Masses are more effective than mingies.’

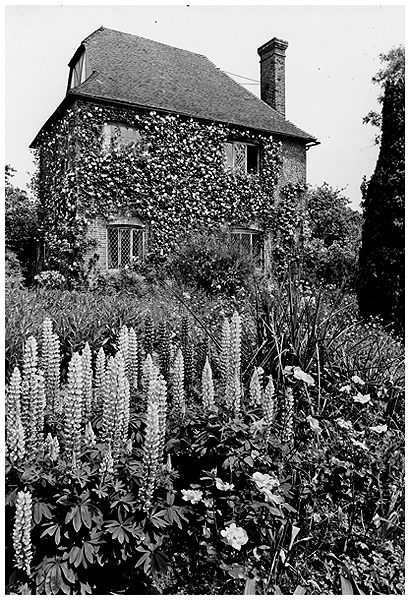

You’ll see this clearly in the photographs of both Long Barn and Sissinghurst from the 1930s until the 1960s, a great profusion, a shagginess, a relaxedness, a softness to almost every hard surface, path, wall or step, as well as all the borders filled to overbrimming. As Anne Scott-James puts it, ‘She planned for rich planting and thick underplanting … the whole garden to be furnished with a lavish hand.’ Lavish is only partly it – it’s also about embroidery and lace and nearly an old-ladyish sort of delicacy.

Go for it, overwhelm with plants, was a keystone of Vita’s Sissinghurst. Don’t plant just one of something – seven or nine, or even six hundred would be better if you can find the money and the room. She liked exaggeration: ‘big groups, big masses; I am sure that it is more effective to plant 12 tulips together than to split them into 2 groups of 6’.

Pam and Sybille, in their continuing development of the garden in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, took this one step further. They would create a strong group of five or seven of one plant on one side of the path and then repeat it in a lesser group on the other. What Vita and then the gardeners were avoiding was the staccato look of dotting singly or in tiny groups, which gave a fussy feel. ‘The more I see of other people’s gardens the more convinced do I become of the value of good grouping and shapely training,’ she declared in In Your Garden Again. ‘These remarks must necessarily apply most forcibly to gardens of a certain size, where sufficient space is available for large clumps or for large specimens of individual plants, but even in a small garden the spotty effect can be avoided by massing instead of dotting plants here and there.’

COVER THE WALLS

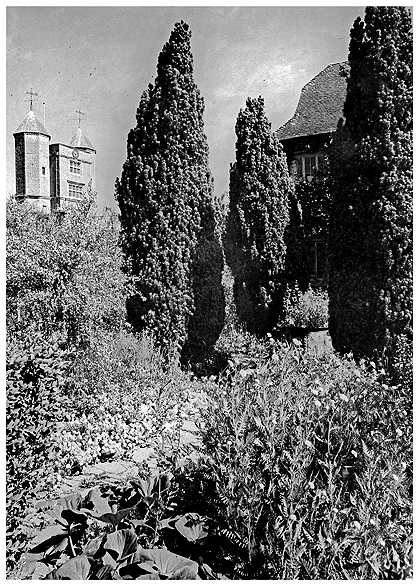

I think Sissinghurst – more than any garden I have seen – uses the vertical as much as the horizontal, every surface brimming over. This is obviously due partly to the number of walls they inherited from the ruined Elizabethan palace. As Vita said very early on, in a letter to Harold in 1930, ‘I see that we are going to have heaps of wall space for climbing things.’ But Vita really went for it, planting the soft-coloured terracotta with hundreds of climbers: roses, clematis, hydrangeas, wisterias. She wanted ‘a tumble of roses and honeysuckle, figs and vines. It was a romantic place, and, within the austerity of Harold Nicolson’s straight lines, must be romantically treated.’

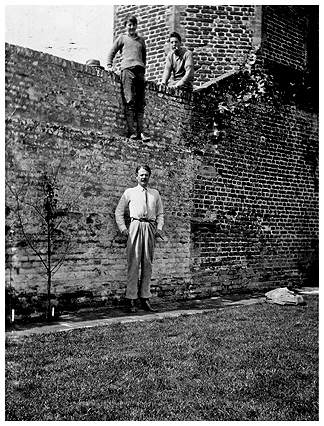

Looking from the Tower to the climber-swagged front range and the table with the bowl for the shilling entrance fee.

As she says, ‘Climbers are among the most useful plants in any garden. They take up little ground space, and they can be employed for many purposes: to clothe a boring fence, to scramble over a dead tree, to frame an archway, to drape a wall, to disguise a shed, or to climb lightly into a pergola. They demand comparatively little attention, once they have taken hold of their support, maybe a yearly pruning or a kindly rescue if they have come adrift in a gale’. This theme has been built on by the gardeners at Sissinghurst ever since.

She’d put lots of climbers and wall shrubs against the house at Long Barn, and wanted even more here. She admitted she had more walls to cover than most of us, but ‘any garden, however small, has a house in it, and that house has walls. This is a very important fact to be remembered. Often I hear people say, “How lucky you are to have these old walls; you can grow anything against them,” and then, when I point out that every house means at least four walls – north, south, east, and west – they say, “I never thought of that.” Against the north and west sides you can grow magnolias or camellias; on the east side, which catches the morning sun, you can grow practically any of the hardy shrubs or climbers, from the beautiful ornamental quinces, commonly, though incorrectly, called Japonicas (the right name is Cydonia, or even more correctly, Chaenomeles), to the more robust varieties of Ceanothus, powdery-blue, or a blue fringing on purple. On the south side the choice is even larger – a vine, for instance, will soon cover a wide, high space, and in a reasonable summer will ripen its bunches of small, sweet grapes (I recommend Royal Muscadine, if you can get it); or, if you want a purely decorative effect, the fast-growing Solanum crispum, which is a potato though you might not think it, will reach to the eaves of the house and will flower in deep mauve for at least two months in early summer.’

The appearance of structural woody climbers – figs, wisterias and osmanthus, pruned flat against the shelter of the red brick and around the windows – is fundamental to the character of Sissinghurst, but Vita did not just leave it at this. She had lots of other things, and a particular passion for climbing and rambler roses, but all these were given only the lightest prune. This was partly because she hated to destroy the bird’s nests, which were almost always in them, but partly because she loved the swathes. Harold complained in a letter: ‘I suppose one must take for granted this birds’-nest passion … I will have to resign myself to my home being an omelet most of the spring and a guano dump the rest of the time.’ She liked the wayward natural growth of yews, not wanting them tightly clipped. She loved shrub roses billowing or even tangling over your head; tall roses – like ‘Nevada’ – tower up right at the edge of the path, columns of shrubs almost obscuring them. Roses were to her a ‘wildly blossoming shrub’ and that’s how they should be grown.

SPRING

For spring Vita planted azara and osmanthus on west-facing walls, their scent in April one of the characteristic smells of the Sissinghurst garden and deliciously strong on a warm day.

Actinidia kolomikta on the west side of the Powys wall.

For its elegant Neapolitan ice-cream, triple-coloured leaves she added actinidia, tucked in a sheltered west-facing corner on the south range, below one of our bedroom windows. It’s a slow grower, but an exotic thing: ‘If you want something which will never exceed 8 to 10 feet let me recommend Actinidia Kolomikta as a plant to set against a wall facing east or west. The small white flowers are insignificant and may be disregarded; the beauty lies in the leaves, which are triple-coloured, green and pink and white, so gay and decorative and unusual as to provoke friends and visitors into asking what it is.’

Akebia is another one, a quick-growing, rampant climber with the delicious and unusual smell of an old-fashioned boiled sweet. I remember seeing this on the main house at Glyndebourne, drawn by its smell that was being thrown twenty yards away. I’d never seen it before, but immediately planted it in my own garden and now – in spring – its scent adds to the medley drifting in through the windows on a warmish day.

As Vita says, ‘[Akebias] are not often seen, but they should be. They are strong growers, semi-evergreen, with shamrock-like leaves and curiously coloured flowers. The flowers of A. trifoliata are brown, and the flowers of A. quinata are of a dusty violet, which might best be described by that neglected adjective, gridelin. Both kinds are hardy, and in a mild climate or after a hot sunny summer will produce fruits the size of a duck’s egg, if you will imagine a duck’s egg in plum-colour, with a plum’s beautiful bloom before it has got rubbed off in the marketing. These fruits have the advantage that their seeds will germinate 100 per cent if you sow them in a pot; at any rate, that has been my experience.’ On Vita’s advice, my mother still has an Akebia quinata with an Actinidia kolomikta growing up a wall next to a Judas tree.

Vita particularly relished the jewel-like flowers of the ornamental quince, and this was one of the first plants she put in as soon as the restoration work was completed on the Big Room walls. I like looking at that plant, the same one that was there seventy years ago and still looking strong and healthy. In In Your Garden Again, Vita notes in October 1951:

‘The ornamental quinces should not be forgotten. They may take a little while to get going, but, once they have made a start, they are there for ever, increasing in size and luxuriance from year to year. They need little attention, and will grow almost anywhere, in sun or shade. Although they are usually seen trained against a wall, notably on old farmhouses and cottages, it is not necessary to give them this protection, for they will do equally well grown as loose bushes in the open or in a border, and, indeed, it seems to me that their beauty is enhanced by this liberty offered to their arching sprays. Their fruits, which in autumn are as handsome as their flowers, make excellent jelly; in fact, there is everything to be said in favour of this well-mannered, easy-going, obliging and pleasantly old-fashioned plant …

‘There are many varieties. There is the old red one, C[ydonia] lagenaria, hard to surpass in richness of colour, beautiful against a grey wall or a whitewashed wall, horrible against modern red brick. There is C. nivalis, pure white, safely lovely against any background. There is C. Moerloosei, or the Apple-blossom quince, whose name is enough to suggest its shell-pink colouring. There is Knaphill Scarlet, not scarlet at all but coral-red; it goes on flowering at odd moments throughout the summer long after its true flowering season is done. There is C. cathayensis, with small flowers succeeded by the biggest green fruits you ever saw – a sight in themselves.’

Beside the japonica Vita planted evergreen myrtle, its leaves so deliciously fragrant when crushed and its black berries so tangy it is not surprising that they are used as flavouring – like juniper’s – with meat. Vita could crumple up a leaf when going in and out of the Big Room and that is why it’s planted there:

‘I have a myrtle growing on a wall. It is only the common myrtle, Myrtus communis, but I think you would have to travel far afield to find a lovelier shrub for July and August flowering. The small, pointed, dark-green leaves are smothered at this time of year by a mass of white flowers with quivering centres of the palest green-yellow, so delicate in their white and gold that it appears as though a cloud of butterflies had alighted on the dark shrub.

‘The myrtle is a plant full of romantic associations in mythology and poetry, the sacred emblem of Venus and of love, though why Milton called it brown I never could understand, unless he was referring to the fact that the leaves, which are by way of being evergreen, do turn brown in frosty weather or under a cold wind. Even if it gets cut down in winter there is nothing to worry about, for it springs up again, at any rate in the South of England. In the north it might be grateful for a covering of ashes or fir branches over the roots. It strikes very easily from cuttings, and a plant in a pot is a pretty thing to possess, especially if it can be stood near the house-door, where the aromatic leaves may be pinched as you go in and out. In very mild counties, such as Cornwall, it should not require the protection of a wall, but may be grown as a bush or small tree in the open, or even, which I think should be most charming of all, into a small grove suggestive of Greece and her nymphs.

‘The flowers are followed by little inky berries, which in their turn are quite decorative, and would probably grow if you sowed a handful of them.’ Like the japonica, this is the same plant put in by Vita in the early 1930s, and I always do as she says, pinching the leaves as I pass.

SUMMER

For summer wall shrubs and climbers, Vita’s favourites were of course the roses. There were so many outstanding ones to choose from and they fitted perfectly – if pruned quite loosely – with her idea of embroidered exuberance, wands arching overhead as well as looping up and over all her walls. ‘How wide is the scope, whether we plant against a wall, or over a bank, or up a pillar, or even an archway, or in that most graceful fashion of sending the long strands up into an old tree, there to soar and dangle, loose and untrammelled,’ she mused.

Roses tumbling off the top of a wall, only lightly pruned.

VITA’S FAVOURITES

‘Albertine’

This is a lovely soft pink rose which Vita mentions as rare among the rambling wichuraianas, in that it’s not prone to mildew even when trained on a wall. ‘Albertine’ is planted to the right of the Tower steps, where it merges with ‘Paul’s Lemon Pillar’, both planted by Vita in the 1930s. There used to be two or three ‘Albertines’ in the Lower Courtyard, but – a slightly tender rose – all but one were lost in the severe winter of 1962/3.

‘Albertine’ roses and ‘Paul’s Lemon Pillar’ with potted plants.

‘Allen Chandler’

This is the rose planted on the entrance arch in the Top Courtyard, planted by Vita in the 30s – ‘A magnificent red, only semi-double, which carries some bloom all through the summer. Not, I think, a rose for a house of new brick, but superb on grey stone, or on white-wash, or indeed any colour-wash.’

‘Lawrence Johnstone’

‘A splendid very deep yellow,’ Vita enthuses, ‘better than the very best butter, and so vigorous as to cover 12 ft. of wall within two seasons. It does not seem to be nearly so well known as it ought to be, even under its old name Hidcote Yellow, although it dates back to 1925 and received an Award of Merit from the R.H.S. in 1948. The bud, of a beautifully pointed shape, opens into a loose, nearly-single flower which does not lose its colour up to the very moment when it drops. Eventually it will attain a height of 50 ft., but if you cannot afford the space for so rampant a grower, you have a sister seedling in Le Rêve, indistinguishable as to flower and leaf, but more restrained as to growth. It must, however, be said that the first explosion of bloom is not usually succeeded by many subsequent flowers.’ This was planted on the South Cottage and is still there.

‘Madame Alfred Carrière’

This was the first rose planted by Vita at Sissinghurst in 1930, before the deeds were even signed, and it quickly covered most of the south face of the South Cottage and in Vita and Harold’s day was left to ‘render invisible’ most of the front of the house and trained around her bedroom window to pour scent into the house for months at a stretch. It is still there, and now has a huge trunk wider than my husband’s thigh.

Rosa ‘Madame Alfred Carrière’ climbing all over South Cottage.

‘If you want a white rose, flushed pink, very vigorous and seldom without flowers,’ she writes, ‘try Mme Alfred Carrière. Smaller than Paul’s rose [see here], and with no pretensions to a marmoreal shape, Madame Alfred has the advantage of a sweet, true-rose scent, and will grow to the eaves of any reasonably proportioned house. It’s best on a sunny wall but tolerant of a west or even a north aspect. I should like to see every Airey house [a prefabricated house built after the Second World War] in this country rendered invisible behind this curtain of white and green.’

‘Mermaid’

‘Perhaps too well known to be mentioned, but should never be forgotten, partly for the sake of the pale-yellow flowers, opening flat and single, and partly because of the late flowering season, which begins after most other climbers are past their best. I must add that Mermaid should be regarded with caution by dwellers in cold districts.’ This turned out to be all too true at Sissinghurst, where Vita planted it on the east-facing wall of the front range. In the severe winter of 1985 it was cut right to the ground and had to be removed. It has been replanted in the Top Courtyard on the east-facing wall to the left of the arch.

Rosa mulliganii on the rose frame in the White Garden, designed by Nigel using paperclips on his desk.

Mulliganii

This is the rose planted at the centre of the White Garden, long thought to be the rose longicuspis. There used to be four, planted to grow up the central path lined with almond trees, but the rose is so rampant, the almonds were starved of light and died. Three of the mulliganii were then removed and the remaining one trained over the central arbour of the White Garden in the 1970s. This is now struggling and recently a new one has been planted to gradually take its place.

‘New Dawn’

This is grown against the wall of the Tower Lawn, where it is only lightly pruned. Its stiffer branches and non-rampant growth mean that its most vigorous stems need only shortening slightly. ‘Among other wichuraianas, of a stiffer character than the ramblers, the New Dawn is to my mind one of the best, very free-flowering throughout the summer, of a delicate but definite rose-pink.’

‘Paul’s Lemon Pillar’

This was planted in two places by Vita at Sissinghurst, against the south-facing wall of the Rose Garden next to the gate into the Top Courtyard, and towards the southwest corner of the Tower Lawn.

‘Another favourite white rose of mine,’ says Vita, ‘is Paul’s Lemon Pillar. It should not be called white. A painter might see it as greenish, suffused with sulphur-yellow, and its great merit lies not only in the vigour of its growth and wealth of flowering, but also in the perfection of its form. The shapeliness of each bud has a sculptural quality which suggests curled shavings of marble, if one may imagine marble made of the softest ivory suede. The full-grown flower is scarcely less beautiful; and when the first explosion of bloom is over, a carpet of thick white petals covers the ground, so dense as to look as though it had been deliberately laid … One of the most perfectly shaped roses I know, and of so subtle a colour that one does not know whether to call it ivory or sulphur or iceberg green.’

‘Paul’s Lemon Pillar’ merging with ‘Albertine’ roses on the Lower Courtyard wall.

PRUNING THE CLIMBING ROSES

Vita liked her climbing roses only lightly pruned, as noted earlier. She loved to see their great tresses climbing up into trees, providing shaggy moustaches and eyebrows to the buildings. They were given only a scant tidy-up in the winter, the dead wood removed, the most rampant growth neatened, but they were never hard shorn. What you got with this pattern of pruning was a great luxuriance of tangled growth each summer, the roses standing out a good two feet from the walls in places, but you got fewer flowers than if they had been pruned more systematically.

Rosa mulliganii pruned hard on its frame in the White Garden.

The gardeners’ policy since Pam and Sybille’s time is to take the roses back to a tight frame. The climbing-rose pruning season at Sissinghurst now starts in November. First, the gardeners cut off most of that year’s growth. This keeps the framework clear and prevents the plant from becoming too woody. Next, large woody stems are taken out – almost to the base – to encourage new shoots. These will flower the following year. The remaining branches are reattached to the wall, stem by stem, starting from the middle of the plant, working outwards, with the pruned tip of each branch bent down and attached to the branch below. That’s the key thing – bending each stem down.

Climbers such as ‘Paul’s Lemon Pillar’ are a bit more reluctant to comply with this treatment than ramblers like ‘Albertine’ and the Rosa mulliganii on the frame in the centre of the White Garden, which are very bendy and easy to train.

MORE OF VITA’S FAVOURITE SUMMER WALL SHRUBS AND CLIMBERS

One of the most significant and large-scale wall plants at Sissinghurst is Magnolia grandiflora with its vast, canoe-shaped leaves all year round, their copper backs just glimpsed as they flicker in the wind. Vita put in two soon after their arrival – one at the entrance and one in the Top Courtyard – and unusually for magnolias, they flower intermittently right through the summer.

‘The flowers … look like great white pigeons settling among dark leaves,’ she noted in 1950. ‘This is an excellent plant for covering an ugly wall-space, being evergreen and fairly rapid of growth. It is not always easy to know what to put against a new red-brick wall; pinks and reds are apt to swear, and to intensify the already-too-hot colour; but the cool green of the magnolia’s glossy leaves and the utter purity of its bloom make it a safe thing to put against any background, however trying. Besides, the flower in itself is of such splendid beauty. I have just been looking into the heart of one. The texture of the petals is of a dense cream; they should not be called white; they are ivory, if you can imagine ivory and cream stirred into a thick paste, with all the softness and smoothness of youthful human flesh; and the scent, reminiscent of lemon, was overpowering.

Magnolia grandiflora.

‘There is a theory that magnolias do best under the protection of a north or west wall, and this is true of the spring-flowering kinds, which are only too liable to damage from morning sunshine after a frosty night, when you may come out after breakfast to find nothing but a lamentable tatter of brown suede; but grandiflora, flowering in July and August, needs no such consideration. In fact, it seems to do better on a sunny exposure, judging by the two plants I have in my garden. I tried an experiment, as usual. One of them is against a shady west wall, and never carries more than half a dozen buds; the other, on a glaring southeast wall, normally carries twenty to thirty. The reason, clearly, is that the summer sun is necessary to ripen the wood on which the flowers will be borne. [Vita’s two original plants are still here at Sissinghurst, one on the west wall of the entrance courtyard, one on a south-facing wall on the top lawn, and the difference in flowering is still apparent.] What they don’t like is drought when they are young, i.e. before their roots have had time to go far in search of moisture; but as they will quickly indicate their disapproval by beginning to drop their yellowing leaves, you can be on your guard with a can of water, or several cans, from the rain-water butt.

‘Goliath is the best variety. Wires should be stretched along the wall on vine-eyes for convenience of future tying. This will save a lot of trouble in the long run, for the magnolia should eventually fill a space at least twenty feet wide by twenty feet high or more, reaching right up to the eaves of the house. The time may come when you reach out of your bedroom window to pick a great ghostly flower in the summer moonlight, and then you will be sorry if you find it has broken away from the wall and is fluttering on a loose branch, a half-captive pigeon trying desperately to escape.’

‘Goliath’ is excellent for a garden on the Sissinghurst scale, as it tends to be very broad-spreading, while there is another cultivar, ‘Harold Poole’, which is smaller in all its parts and so would fit in a smaller garden. ‘Samuel Sommer’ has the largest flowers of all, which can be over a foot across, yet it’s not a massive grower and is said to be particularly hardy. It’s ideal for those with smaller gardens.

There were relatively few clematis at Sissinghurst until Pam and Sybille arrived in 1959. Sybille remembers going with Vita to Christopher Lloyd’s garden and nursery at Great Dixter in East Sussex to help her select a few. They gradually put in more and more, favouring particularly the late-flowering viticellas, which were resistant to the destructive fungus, clematis wilt.

‘However popular, however ubiquitous, the clematis must remain among the best hardy climbers in our gardens,’ Vita writes. ‘Consider first their beauty, which may be either flamboyant or delicate. Consider their long flowering period, from April till November. Consider also that they are easy to grow; do not object to lime in the soil; are readily propagated, especially by layering; are very attractive even when not in flower, with their silky-silvery seed heads, which always remind me of Yorkshire terriers curled into a ball; offer an immense variety both of species and hybrids; and may be used in many different ways, for growing over sheds, fences, pergolas, hedges, old trees, or up the walls of houses. The perfect climber? Almost, but there are two snags which worry most people.

‘There is the problem of pruning. This, I admit, is complicated if you want to go into details, but as a rough working rule it is safe to say that those kinds which flower in the spring and early summer need pruning just after they have flowered, whereas the later flowering kinds (i.e., those that flower on the shoots they have made during the current season) should be pruned in the early spring.

‘The second worry is wilt. You may prefer to call it Ascochyta Clematidina, but the result is the same, that your most promising plant will suddenly, without the slightest warning, be discovered hanging like miserable wet string. The cause is known to be a fungus, but the cure, which would be more useful to know, is unknown. The only comfort is that the plant will probably shoot up again from the root; you should, of course, cut the collapsed strands down to the ground to prevent any spread of the disease. It is important, also, to obtain plants on their own roots, for they are far less liable to attack … Slugs, caterpillars, mice, and rabbits are all fond of young clematis, but that is just one of the normal troubles of gardening. Wilt is the real speciality of the clematis.

‘There is much more to be said about this beautiful plant but space only to say that it likes shade at its roots, and don’t let it get too dry.’

Clematis ‘Perle d’Azur’ on the Powys wall.

The clematis ‘Perle d’Azur’ is one of the iconic plants of Sissinghurst, growing on the semicircular wall in the Rose Garden. This was planted after Vita’s day, by Pam and Sybille. It forms a majestic mauve backcloth to the Rose Garden for many weeks in late summer. This is no mean feat – it is very elaborately trained to achieve such drama. The wall is covered with six-inch netting above the clematis. The plant is cut back hard in late autumn and every ten days in May and June, then carefully spread out over the wall as it grows, with new growth tied in as you might do for your tomatoes or sweet peas. The gardeners use paper-covered wire twists so as to be more gentle to the stems, and attach the new stems to the wire behind with these.

There have also been lots of clematis on the wall along the back of the Purple Border, six or seven merging into a great curtain of crimson and purple, varieties chosen to overlap but flower in succession to give the maximum weeks of interest to this high-summer border. There is an ingenious system of wiring that goes over the top of the wall, bridging one side and the other with sheep netting. When the clematis reaches the top, rather than being blown around like a huge sail and then collapsing back on itself, it clings to the wire, which then carries it from the Top Courtyard side into the garden known as Delos.

SUMMER AND AUTUMN

Vita was also very fond of four other slightly tender wall plants, which added a bit of exoticism to her walls. The first was the shrub Abutilon megapotamicum, which she picked as one of her favourite plants in her short book, Some Flowers, published in 1937. She decribes it at length:

‘This curious Brazilian with the formidable name is usually offered as a half-hardy or greenhouse plant, but experience shows that it will withstand as many degrees of frost as it is likely to meet with in the southern counties. It is well worth trying against a south wall, for apart from the unusual character of its flowers it has several points to recommend it. For one thing it occupies but little space, seldom growing more than four feet high, so that even if you should happen to lose it you will not be left with a big blank gap. For another, it has the convenient habit of layering itself of its own accord, so that by merely separating the rooted layers and putting them into the safety of a cold frame, you need never be without a supply of substitutes. For another, it is apt to flower at times when you least expect it, which always provides an amusing surprise …

Abutilon megapotamicum.

‘It is a thing to train up against a sunny south wall, and if you should happen to have a whitewashed wall or even a wall of grey stone, it will show up to special advantage against it … It is on the tender side, not liking too many degrees of frost, so should be covered over in winter …

‘You should … grow it where you are constantly likely to pass and can glance at it daily to see what it is doing. It is not one of those showy climbers which you can see from the other side of the garden, but requires to be looked at as closely as though you were short-sighted. You can only do so in the open, for if you cut it to bring into the house it will be dead within the hour, which is unsatisfactory both for it and for you. But sitting on the grass at the foot of the wall where it grows, you can stare up into the queer hanging bells and forget what the people round you are saying. It is not an easy flower to describe – no flower is, but the Abutilon is particularly difficult. In despair I turned up its botanically official description: “Ls. lanc, 3, toothed. Fls. 1½, sepals red, petals yellow, stamens long and drooping (like a fuchsia)”.

‘Now in the whole of that laconic though comprehensive specification there were only three words which could help me at all: like a fuchsia. Of course I had thought of that already; anybody would. The flower of the Abutilon is like a fuchsia, both in size and in shape, though not in colour. But it is really a ballet dancer, something out of Prince Igor. “Sepals red, petals yellow” is translated for me into a tight-fitting red bodice with a yellow petticoat springing out below it in flares, a neat little figure, rotating on the point of the stamens as on the point of the toes. One should, in fact, be able to spin it like a top.’ This abutilon has recently been planted in a very prominent position to cover the front of the South Cottage, sharing the south-facing wall there with Rosa ‘Madame Alfred Carrière’.

Her next recommendation is for campsis (known then as bignonia), a very luscious plant with large, deep burnt-orange trumpet flowers which you see much more commonly on the Continent than in gardens here. This may get cut to the ground in a hard winter, but usually re-emerges just as well the following spring and can romp its way up over the top of a barn roof in no time:

‘They are so showy and so decorative … Their big orange-red trumpets make a noise like a brass band in the summer garden. They are things with a rather complicated botanical history, often changing their names. Bignonia grandiflora is now known as Campsis grandiflora (it went through a phase of calling itself Tecoma) and Bignonia radicans is now Campsis radicans. The best variety of it is Mme Galen; and as it has rather smaller flowers than grandiflora, a friend of mine calls it Little-nonia, a poor joke that will not appeal to serious gardeners, but may be helpful to the amateurs who wish to remember the difference.

‘They all want a sunny wall, and should be pruned back like a vine, that is, cut right hard back to a second “eye” or bud, during the dormant season between November and January. Like a vine, again, they will strike from cuttings taken at an eye and pushed firmly into sandy soil.’ Campsis was, and still is, planted on the moat wall where it tumbles from the orchard side, the flowers almost echoing the colour of the brighter bricks.

Cobaea scandens on the Erechtheum.

Vita also enjoyed the exotic-looking cup-and-saucer plant, Cobaea scandens, and planted this on the east-facing wall of the south range in the Top Courtyard and on the Erechtheum, where it is still planted every year today. It reaches not eight to ten foot high, as Vita suggests below, but thirty, right up to our daughter Molly’s bathroom window on the second floor.

Vita tells her readers: ‘An interesting and unusual plant which should find a place is Cobaea scandens, which sounds more attractive under its English name of cups-and-saucers. This is a climber, and an exceedingly rapid one, for it will scramble eight to ten feet high in the course of a single summer. Unfortunately it must be regarded as an annual in most parts of this country, and a half-hardy annual at that, for although it might be possible with some protection to coax it through a mild winter, it is far better to renew it every year from seed sown under glass in February or March. Pricked off into small pots in the same way as you would do for tomatoes, it can then be gradually hardened off and planted out towards the end of May. In the very mild counties it would probably survive as a perennial.

‘It likes a rich, light soil, plenty of water while it is growing, and a sunny aspect. The ideal place for it is a trellis nailed against a wall, or a position at the foot of a hedge, when people will be much puzzled as to what kind of a hedge this can be, bearing such curious short-stemmed flowers, like a Canterbury Bell with tendrils. Unlike the Canterbury Bell, however, the flowers amuse themselves by changing their colour. They start coming out as a creamy white; then they turn apple-green, then they develop a slight mauve blush, and end up a deep purple. A bowl of the mixture, in its three stages, is a pretty sight, and may be picked right up to the end of October.’ I find these last a few more days in water if you sear the stem ends (see here).

Similar in feel to the cup-and-saucer plant and also useful for picking and floating in a shallow bowl for a table, Vita liked the Passion flower, Passiflora caerulea, ‘which is hardier than sometimes supposed, springing up from its roots again yearly, even if it has been cut down to the ground by frost and has apparently given up all attempt to live. Its strangely constructed flowers are not very effective at a distance, but marvellous to look into, with the nails and the crown of thorns from which it derives its name. It should be grown against a warm wall, though even in so favoured a situation I fear it is unlikely to produce its orange fruits in this country.’ Later, she added: ‘I must go back on this remark. Plants on two cottages near where I live, in Kent, produce a truly heavy crop of fruits. I could not think what they were till I stopped to investigate. The curious thing is that both plants are facing due east, and can scarcely receive any sun at all.’

And a last word: ‘There is a white variety called Constance Elliott. I prefer the pale blue one myself; but each to his own taste.’

VITA’S TOP SHRUBS AND CLIMBERS

FOR A SOUTH WALL

Abutilon megapotamicum

Indigoferas

Solanum crispum var. autumnalis, ‘so useful in August – a trifle tender, perhaps, wanting a warm south wall’

Solanum jasminoides, white, ‘another August flowerer, a most graceful climber, also a trifle tender but well worth trying in southern counties’

Vine ‘Royal Muscadine’

FOR A NORTH WALL

Clematis flammula

Garrya elliptica

Kerria japonica

Morello cherry

Winter jasmine

FOR A NORTH OR WEST WALL

Camellias

Magnolias

Osmanthus

Wisteria

FOR AN EAST WALL

Hardier ceanothus

Japonica (ornamental quince)

COVER THE TREES

When I ask my mother how Vita influenced my parents’ garden most of all, she remembers Vita’s passion for growing climbers and particular roses up into trees. She still has several roses grown like that in their garden in the village of Shepreth, just outside Cambridge, a garden mainly planted in the late 1950s, when through her Observer columns Vita’s influence was most felt. There is ‘Madame Alfred Carrière’ up a Bramley apple tree, ‘Albéric Barbier’ up a rhus, ‘Crimson Conquest’ up a white-flowered lilac and ‘Wickwar’ up a euonymus by the house.

Vita liked to decorate the trees, and is well known for using the apple and pear trees in the Sissinghurst Orchard and the almonds in the centre of the new White Garden as climbing frames for clematis and roses, sometimes at the cost of the tree beneath the rampant canopy. The soft pink rose ‘Flora’ is the one remaining, clambering right to the top of a soft prunus outside the door of the Priest’s House. She recommends ivy and vines too – of the right varieties – as well as Clematis montana and the tricolour-leaved actinidia (see also here):

‘We do not make nearly enough use of the upper storeys. The ground floor is just the ground, the good flat earth we cram with all the plants we want to grow. We also grow some climbers, which reach to the first-floor windows, and we may grow some other climbers over a pergola, but our inventiveness usually stops short at that. What we tend to forget is that nature provides some far higher reaches into which we can shoot long festoons whose beauty gains from the transparency of dangling in mid-air. What I mean, briefly, is things in trees …

‘There is no need to stick to ivy. The gadding vine will do as well. The enormous shield-shaped leaves of Vitis coignetiae, turning a deep pink in autumn, amaze us with their rich cornelian in the upper air, exquisitely veined and rosy as the pricked ears of an Alsatian dog. Then, if you prefer June–July colour to October colour, there is that curious vigorous climber, Actinidia kolomikta, which starts off with a wholly green leaf, then develops white streaks and a pink tip, and puzzles people who mistake its colouring habits for some new form of disease. Cats like it: and so do I, although I don’t like cats.’

Vita also suggests a vigorous climber such as Clematis montana for a large tree. ‘[It] should soon clothe it to the top; this small-flowered clematis can be had in its white form, or in the pink variety, rubra. The so-called Russian vine, Polygonum baldschuanicum, most rapid of climbers, will go to a height of 20 ft. or more, and is attractive with its feathery plumes of a creamy white. It should scarcely be necessary to emphasize the value of the wisterias for similar purpose.

‘One advantage of this use of climbers for a small garden is the saving of ground space. The soil, however, should be richly made up in the first instance, as the tree-roots will rob it grossly, and will also absorb most of the moisture, so see to it that a newly planted climber does not lack water during its first season, before it has had time to become established and is sending out its own roots far enough or deep enough to get beyond the worst of the parched area.’

VITA’S TOP TREE-CLIMBING ROSES

All three of these roses were planted by Vita in the Orchard and two are still there, but not on trees.

‘Félicité et Perpétue’

‘Commemorating two young women who suffered martyrdom at Carthage in A.D. 205’, Vita recommends this for growing on a tree. On a wall it can get mildew, but on a tree ‘it will grow at least 20 ft. high into the branches, very appropriately, since St. Perpetua was vouchsafed the vision of a wonderful ladder reaching up to heaven’. Vita planted this in the Orchard to climb into a pear tree. The tree has died and a new rose has been planted, but this one is rather too tidily trained over a chestnut frame.

Rosa filipes ‘Kiftsgate’

‘If you want a very vigorous climber, making an incredible length of growth in one season, do try to obtain Rosa filipes,’ Vita urges. ‘It is ideal for growing into an old tree, which it will quickly drape with pale-green dangling trails and clusters of small white yellow-centred flowers. I can only describe the general effect as lacy, with myriads of little golden eyes looking down at you from amongst the lace. This sounds like a fanciful description, of the kind I abhor in other writers on horticultural subjects, but really there are times when one is reduced to such low depths in the struggle to convey the impression one has oneself derived, on some perfect summer evening when everything is breathless, and one just sits, and gazes, and tries to sum up what one is seeing, mixed in with the sounds of a summer night – the young owls hissing in their nest over the cowshed, the bray of a donkey, the plop of an acorn into the pool.

‘Filipes means thread-like, or with thread-like stems, so perhaps my comparison to lace is not so fanciful, after all. Certainly the reticulation of the long strands overhead, clumped with the white clusters, faintly sweet-scented, always makes me think of some frock of faded green, trimmed with Point d’Alençon – or is it Point de Venise that I mean?’

‘Madame Plantier’

‘I am astonished, and even alarmed, by the growth which certain roses will make in the course of a few years. There is one called Madame Plantier, which we planted at the foot of a worthless old apple tree, vaguely hoping that it might cover a few feet of the trunk. Now it is 15 feet high with a girth of 15 yards, tapering towards the top like the waist of a Victorian beauty and pouring down in a vast crinoline stitched all over with its white sweet-scented clusters of flower.

‘Madame Plantier dates back, in fact, to 1835,’ Vita continues, ‘just two years before Queen Victoria came to the throne, so she and the Queen may be said to have grown up together towards the crinolines of their maturity. Queen Victoria is dead, but Madame Plantier still very much alive. I go out to look at her in the moonlight: she gleams, a pear-shaped ghost, contriving to look both matronly and virginal. She has to be tied up round her tree, in long strands, otherwise she would make only a big straggly bush. We have found that the best method is to fix a sort of tripod of bean-poles against the tree and tie the strands to that.’

This was another rose planted in the Orchard to climb into a tree, but Pam and Sybille felt it to be too rampant. It quickly smothered the old apple tree, and itself grew rapidly so huge that it became difficult and very time-consuming to prune. It has collapsed now into a mound of nothing but rose, the remains of the tree buried underneath.

COVER THE GROUND

To achieve the feeling of maximum fullness, Vita crams things at ground level, as well as overhead:

‘The more I prowl round my garden at this time of year, especially during that stolen hour of half-dusk between tea and supper, the more do I become convinced that a great secret of good gardening lies in covering every patch of the ground with some suitable carpeter. Much as I love the chocolate look of the earth in winter, when spring comes back I always feel that I have not done enough, not nearly enough, to plant up the odd corners with little low things that will crawl about, keeping weeds away, and tuck themselves into chinks that would otherwise be devoid of interest or prettiness.

Every patch of ground is covered in the Cottage Garden, 1962.

‘The violets, for instance – I would not despise even our native Viola odorata of the banks and hedgerows, either in its blue or its white form, so well deserving the adjective odorata. And how it spreads, wherever it is happy, so why not let it roam and range as it listeth? (I defy any foreigner to pronounce that word.) There are other violets, more choice than our wildling; the little pink Coeur d’Alsace, or Viola labradorica [still at Sissinghurst, as a carpeter], for instance, which from a few thin roots planted last year is now making huge clumps and bumps of purplish leaf and wine-coloured flower, and is sowing itself all over the place wherever it is wanted or not wanted. It is never not wanted, for it can be lifted and removed to another place, where it will spread at its good will.

‘There are many other carpeters beside the violets, some for sunny places and some for shade. For sunny places the thymes are perhaps unequalled, but the sunny places are never difficult to fill. Shady corners are more likely to worry the gardener trying to follow my advice of cram, cram, cram every chink and cranny. Arenaria balearica loves a dark, damp home, especially if it can be allowed to crawl adhesively over mossy stones. On a dark green mat it produces masses of what must be one of the tiniest flowers, pure white, starry; an easy-going jewel for the right situation. Cotula squalida is much nicer than its name: it is like a miniature fern, and it will spread widely and will help to keep the weeds away.

‘The Acaenas will likewise spread widely, and should do well in shade; they have bronzy-coloured leaves and crawl neatly over their territory. The list of carpeters is endless, and I wish I had enough space to amplify these few suggestions. The one thing I feel sure of is that every odd corner should be packed with something permanent, something of interest and beauty, something tucking itself into something else in the natural way of plants when they sow themselves and combine as we never could combine them with all our skill and knowledge.’

COVER THE PATHS

Apart from the walls, the paths and steps were the main hard structures in each of the garden rooms. They were designed by Harold and laid in the first two or three years after their arrival. They could not always afford the vast expanses of York stone called for, and so in the less prominent paths, away from the entrance and the formal axes and vistas, they sometimes used a mix of materials.

‘Tramplees’ swathing the steps at the northern end of the White Garden.

In the Cottage Garden, Harold designed a scheme using brick with stone; in the Rose Garden, the main path was grass, and the side paths were left as grass, as they had been when this was the kitchen garden; in the Lime Walk the paths were made not just from concrete, but the surprising thing was that they were coloured, a mix of red, yellow and green. That is one of the few mystifying decisions Harold made, the colours luckily fading quite quickly, and the concrete has now been replaced by York stone.

Harold often designed wide sweeps of paths in the knowledge that Vita would soon be covering them with plants, both in between the stones and creeping in from the sides. Vita sets down her thoughts on the subject:

‘The first essential [for planting in paths] is that it shall be something which does not mind being walked upon. There was once a play called Boots and Doormats, which divided people into two categories: those who liked to trample and those who enjoy being trampled. To-day, in modern jargon, I suppose they would be called tramplers and tramplees; I prefer boots and doormats as an expression of this fundamental truth. Many big boots will walk down a paved path, and there are some meek doormats prepared to put up with such gruff treatment. The creeping thymes really enjoy being walked on, and will crawl and crawl, spreading gradually into rivulets and pools of green, like water slowly trickling, increasing in volume as it goes, until they have filled up all the cracks and crevices. The thymes are the true standby for anybody who wants to carpet a paved path.

‘There are other tramplees also. Pennyroyal does not mind what you do with it, and will give out its minty scent all the better for being bruised underfoot. Cotula squalida … has tiny fern-like leaves, cowering very close down; no flower, but very resistant to hard wear and very easy to grow. All the Acaenas are useful; Acaena Buchananii, a silver-green, or Acaena microphylla, bronze in colour. A pity that such tiny things should have such formidable names, but they are neither difficult to obtain nor to establish.’

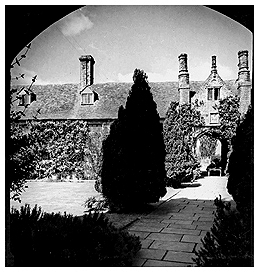

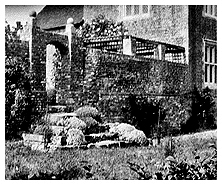

Paths and steps almost invisible under carpets of plants at Long Barn.

You can see this in the garden at Long Barn, where all the hard surfaces were almost covered by curtains of rock roses, smaller species of roses, cistus, azaleas and rosemary, swathing the stone or brick from each side. This was a theme which Vita carried on at Sissinghurst and something that contributed hugely to the overall abundant feel of almost every part of the garden. Edwin Smith captures it brilliantly in his photograph of the Cottage Garden, taken in 1962 (see here).

Vita goes further, suggesting ‘filling up the cracks’ in the path or steps ‘with good soil or compost, and sow[ing] seeds quite recklessly. I should not mind how ordinary my candidates were, Royal Blue forget-me-not, pansies, wallflowers, Indian pinks, alyssum Violet Queen, because I should pull up 95 per cent later on, leaving only single specimens here and there. It is not, after all, a flower-bed that we are trying to create. If, however, you think it is a waste of opportunity to sow such ordinary things, there are plenty of low-growing plants of a choicer kind, especially those which dislike excessive damp at the root throughout the winter: this covering of stone would protect them from that. The old-fashioned pinks would make charming tufts: Dad’s Favourite, or Inchmery, or Little Jock, or Susan, or Thomas. The Allwoodii, with their suggestion of chintz and of patchwork quilts, should also succeed under such conditions.’

SELF-SOWING AND PRETEND SELF-SOWING

Allowing self-sowing of favourite annuals and biennials was another essential thread, and very much part of Vita’s cram-cram-cram design. She liked the random appearance of things, which often cropped up in plant combinations that were much better than one would have thought of oneself, as well as the freedom this gave to the feel of a garden – aubrieta, lupins, dill, poppies and thyme all left in the cracks in the paths and steps, or in the edges of the beds, as they came up.

She also liked the abundance self-sowing gave you, the miraculous appearance suddenly of many hundreds of Californian poppies in the cracks of the Lime Walk paths, which she banned the gardeners from weeding out, and she writes about walking round the garden with canes to mark things that popped up, volunteering themselves, which she wanted left just where they were.

Vita also loved to encourage a few select wild flowers to make their home in the garden. Not of course the brutes such as nettles and docks, but she liked to see daisies ‘enamelling’ the lawn. Columbines were always left to seed themselves and the dark-foliaged Viola labradorica, mentioned earlier, was allowed where it would. Both Vita and Harold hated gardens to be over-tamed or over-trimmed. As Anne Scott-James commented, ‘To Vita, Sissinghurst always remained the Sleeping Beauty’s castle, and though she was willing to clear a tangle of a hundred slumbering years she did not want the garden scrubbed clean. It was to be hospitable to wildlings.’

She took this one step further and actually planted seedlings of rosemary and wallflowers into the cracks in the Tower steps and the Moat Walk wall in a random way to make them look as if they were self-sown. There are lots of wild ivy-leaved toadflax in the Sissinghurst walls and some clumps of the yellow-flowered wild corydalis, but Vita wanted to add greater variety.

At Long Barn, on a sloping site, Vita and Harold had created great lengths of terraced walls so as to level it, and inserted Cheddar pinks, lavender, aubrietas, cistus and even species tulips into them, an idea she’d got from the terraced olive groves in southern Spain, adding these things to the walls as they were being built and then hoping they’d self-sow.

‘How envious one feels of the terraced hillsides of the south,’ she writes, ‘for there are few more delightful or satisfactory forms of gardening than dry-wall gardening. Plants can run their roots right back into the cool soil between stones, finding every drop of moisture even in a dry season, and can open their faces to the sun on the wall-front. I write these words in Spain, wishing that I could bring home even one length of the rough walling, probably many hundreds of years old …

‘English people who live in a stone country such as the Cotswolds or the Lake District are fortunate in that they may be able to assemble sufficient stones at little cost. The important thing to remember is that the wall-front should be on a batten, i.e. sloping slightly backwards from the base to the top, and that each stone should be tilted back as it is laid in place, packed with good soil, for you must remember that the soil can never be renewed short of taking the whole wall to pieces. If you can plant as you go, layer by layer, so much the better, for then the roots can be spread out flat instead of ramming them in later on, cramped, constricted, and uncomfortable. This method also enables you to vary the soil according to the requirements of its occupant: peat, or grit, can be added or withheld at will.

‘The top of the wall is full of possibilities. (I am assuming that your dry-wall is a retaining wall, built against a bank.) Not only can you fill it with things like lithospermum or pinks, or that pretty little rosy gypsophila called fratensis, to hang down in beards, on the wall-face, but a number of small bulbs will also enjoy the good drainage and will blow at eye-level where their delicate beauty can best be appreciated.

‘I can think of many small subjects for such a kingdom. The Lady-tulip, Tulipa clusiana, striped pink-and-white like a boiled sweet from the village shop, might survive for many more seasons than is usual in a flat bed. The little Greek tulip orphanidea would also be happy, in fact all the bulbs which in their native countries are accustomed to stony drought all through the summer. The dwarf irises would give colour in the spring, and their grey-green leaves would look tidy all the year round. Ixias, so graceful, for a later flowering. Lavender stoechas, which is all over these Spanish hills, should not damp off as it is apt to do in an ordinary border. This lavender would form agreeable clumps between the bulbs; fairly dwarf, it makes a change from the usual lavenders, such as the deep purple nana atropurpurea. Clip them close, when the flower-spike is going over, to keep them neat and rounded.’

There could not be this range of plants crammed into the walls as if self-sown at Sissinghurst, because the brick-built – rather than stone – walls would not allow it, but it is still very much a theme in the planting style, particularly noticeable on the Moat Walk wall. When the wall was restored in the 1990s the gardeners felt it had been done too perfectly, without any planting holes left. So they carefully picked out small pockets in the brickwork into which they could then plant things.

Every year the perennial wallflower, Erysimum ‘Bowles Mauve’, is added in small plugs. These are done as cuttings rooted into Jiffy pots, which can then be pressed into the holes, supplementing those that are still there from the year before. For every two, only one takes, and then survives for about four years. I’m sure Vita would very much approve.