7

FLOWERING SHRUBS

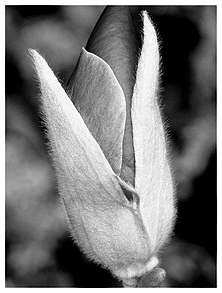

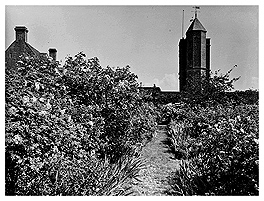

Magnolias framing the view from the White Garden, looking through the Bishop’s Gate.

Vita’s view, certainly as time went on, was that once you have the ‘bones’ of your garden, the walls and hedges, in place, you then need to fill them out in a carefully balanced way, the first layer of flesh almost as planned as the bones themselves. She needed to think about introducing large-scale plants which would give a real sense of architecture, adding another layer to Harold’s design.

In the 1950s Vita wrote about her regrets that she had not got on with more structural planting straight away at Sissinghurst, but as the years went by, more and more large plants were added to the borders, things that would give ‘a sense of substance and solidity’, a topography, some ups and downs, a shape and a rhythm, as well as that all-important feeling of fullness which would carry through even into the winter:

‘It is a truly satisfactory thing to see a garden well schemed and wisely planted. Well schemed are the operative words. Every garden, large or small, ought to be planned from the outset, getting its bones, its skeleton, into the shape that it will preserve all through the year even after the flowers have faded and died away. Then, when all colour has gone, is the moment to revise, to make notes for additions, and even to take the mattock for removals. This is gardening on the large scale, not in details. There can be no rules in so fluid and personal a pursuit, but it is safe to say that a sense of substance and solidity can be achieved only by the presence of an occasional mass breaking the more airy companies of the little flowers.

‘What this mass shall consist of must depend upon many things: upon the soil, the aspect, the colour of neighbouring plants, and above all upon the taste of the owner … The possibilities of variation are manifold, but on the main point one must remain adamant: the alternation between colour and solidity, decoration and architecture, frivolity and seriousness. Every good garden, large or small, must have some architectural quality about it; and, apart from the all-important question of the general lay-out, including hedges, the best way to achieve this imperative effect is by massive lumps of planting.’

Vita wanted her ‘massive lumps’ to come from shrubs, particularly flowering forms. ‘The alternative’ to the herbaceous border, she wrote in October 1951, ‘is a border largely composed of flowering shrubs, including the big bush roses … it is possible to design one which will (more or less) look after itself once it has become established.’ This was increasingly important. With the memories of recent war and the challenges that Vita faced with only one gardener there to help at that time, to have a flower garden that didn’t need intensive maintenance was at the forefront of her mind.

Many of the plants she cherished and planted at Sissinghurst are now well known – shrubs and small trees such as Prunus subhirtella ‘Autumnalis’, Hoheria lyallii, Hydrangea paniculata ‘Grandiflora’, and the pretty early-flowering almond. These were rarer, more obscure and much less readily available in the days when she was championing them – her ‘faithful friends’, as she called them. Many of these still remain the best today, though shrubs such as hoheria are surprisingly rarely planted even now.

It was with plants such as these that you could get a massed effect with minimal maintenance: ‘The main thing, it seems to me, is to have a foundation of large, tough, un-troublesome plants with intervening spaces for the occupation of annuals, bulbs, or anything that takes your fancy.’

She puts their case again and again:

‘Those gardeners who desire the maximum of reward with the minimum of labour would be well advised to concentrate upon the flowering shrubs and flowering trees. How deeply I regret that fifteen years ago, when I was forming my own garden, I did not plant these desirable objects in sufficient quantity. They would by now be large adults instead of the scrubby, spindly infants I contemplate with impatience as the seasons come round.

‘That error is one from which I would wish to save my fellow-gardeners, so, taking this opportunity, I implore them to secure trees and bushes from whatever nurseryman can supply them: they will give far less trouble than the orthodox herbaceous flower. They will demand no annual division, many of them will require no pruning; in fact, all that many of them will ask of you is to watch them grow yearly into a greater splendour, and what more could be exacted of any plant?’

She adds at a later date: ‘The initial outlay would seem extravagant, but at least it would not have to be repeated, and the effect would improve with every year.’

Vita – as in all her gardening – was a great experimenter, always wanting to try out new things and ready to uproot them if they failed to impress. She was advised on potentially interesting shrubs by Norah Lindsay, the renowned between-the-wars garden designer, and Collingwood (often called ‘Cherry’) Ingram, an expert on the prunus family, who lived in Benenden, only a village away. Both had a great influence on what was chosen and planted all through the garden; there would be a process of filtering, with things coming in, some then staying, others being ripped out, or moved from one place to another.

Through this filtering, Vita ended up with some lifelong favourites, many of which she wrote about in her Observer columns. As we have seen, there are other shrubs and climbers she liked for positioning against the many walls, but it’s the flowering shrubs in the following list to which she turned as the main decorative shapes for her flower beds.

VITA’S TOP SHRUBS AND TREES

WINTER

Many of the best winter-flowering shrubs, such as hamamelis, mahonias, wintersweet, are scented (see here) – Vita loved these for picking too, so they have their own section (see here) – but she also included camellias in her early structural planting.

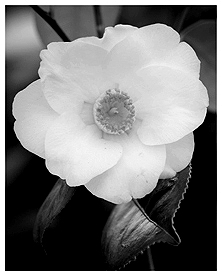

Camellia ‘Alba Simplex’.

She liked the single Camellia ‘Alba Simplex’, which she planted in the White Garden and the southwest corner of the Top Courtyard where it still is today. This is the most elegant variety, with very dark green, shiny foliage. I also grow it and love it for its simplicity compared to so many camellias that have a slightly plastic texture and an artificial-looking pink or red colour. ‘Alba Simplex’ is pure white around a golden centre packed with anthers and pollen.

Vita also grew the pink ‘Donation’, planted in the Tower beds in the Top Courtyard, and had this as a pot plant, grown in her cold greenhouse. She could then bring it in in the early spring to cheer up a dingy corner.

SPRING

Our bedroom window looks east, so that on a good spring morning we look out first thing at a sun rising behind the trees in the garden. There are several magnolias here, and in a year when there are no late frosts they glow in that first sunlight as if laden with lit candles, their branches peering over the garden walls. So often magnolias are full of promise in that first emergence of their buds, but then get nailed – literally browned off in the cold spring weather; but when they don’t, they tower over the garden as its most flamboyant spring climax.

Of course, trees grow, and so if a magnolia does well it becomes more magnificent with every passing year. These particular ones, mostly put in by Vita in Delos and the Lower Courtyard, are now huge, like hot-air balloons of flowers, giving a massive third dimension to the garden.

Magnolias were one of her favourite garden trees – Vita would love to see them now.

‘Many people hesitate to plant that most noble of flowering trees, the magnolia,’ she writes, ‘under the impression that they will never live long enough or remain for long enough in the same place to see it flower. It is true that some kinds of magnolia are not suitable for a short-term tenancy. Magnolia campbellii, for instance, may demand twenty-five years before it pays any dividend on its original cost. [It also grows to about a hundred foot!] But this is not true of some other kinds.

‘The Yulan tree, M. denudata, produces a few of its creamy chalices within a year or two of planting, and increases in size and fertility until it is one hundred years old or more. I planted one twenty years ago, and it has long since achieved a height of 20 ft. and a spread of 15 ft. So you see. Its only serious enemy, very serious indeed, is a March frost which may turn its candid purity to a leathery khaki brown. Sometimes it escapes; one must take the risk; it is worth taking.

‘It is best planted in April or May, and the vital thing to remember is that it must never be allowed to suffer from drought before it has become established. Once firmly settled into its new home, it can be left to look after itself. Avoid planting it in a frost pocket, or in a position where it will be exposed to the rays of a warm sun after a frosty night: under the lee of a north or west wall is probably the ideal situation, or within the shelter of a shrubbery.

‘… people who for reasons of limited space feel unwilling to take the risk, in spite of the immense reward in a favourable season, would be better advised to plant the later-flowering Magnolia Soulangeana, less pure in its whiteness, for the outside of the petals is stained with pink or purple; or Magnolia Lennei, which is frankly rosy, but very beautiful with its huge pink goblets, and seldom suffers from frost unless it has extremely bad luck at the end of April.

‘M. stellata, which also flowers in extreme youth, is perhaps the most familiar of all the magnolias to be seen in the amateur gardener’s garden. To my way of thinking, it is by no means one of the most beautiful, being ragged and tattered-looking, but a well-grown bush is certainly effective, seen at a distance.’

Magnolia soulangeana ‘Lennei’.

Vita’s dismissal of stellata is a bit tough, as it’s the one a lot of people like best. It’s the classic for a small town garden with its widely spaced, spidery-petalled flowers, and makes a compact plant, shrubbier than most. It’s also one of the earliest to bloom and its flowers are more resistant to frost, so they often look good for most of the spring. All magnolias have wonderful buds, like furry mice sitting on the branch. You can really see – and feel – them with any of the stellata forms.

She continues: ‘M. salicifolia is one of the easiest and hardiest, and its flowers are less susceptible to frost than either the Yulan or M. stellata … Or, if you want something really sumptuous, there is the claret-coloured M. liliiflora nigra, which in my experience flowers continuously for nearly two months, May and June; it is a good plant for small gardens, as it grows neither too high nor too wide, and I have never known it fail to flower copiously every year.’ Vita planted the deep, rich M. liliiflora ‘Nigra’ in the southeast corner of the Tower Lawn. The liliiflora has been replanted recently, but it’s now filling out.

‘I have not even mentioned that the magnolia is easygoing as to soil,’ she adds. ‘[It] likes some peat or leaf-mould but does not exact it; appreciates a rich mulch from time to time; is rather brittle and thus prefers a sheltered to a windy position; and should be transplanted in spring (March) rather than in autumn.’

On a smaller scale, Vita favoured for spring other flowering shrubs including corylopsis, deutzias and kolkwitzias. Corylopsis pauciflora is a delicate thing, with pagoda-like primrose-yellow flowers. She describes it as ‘a little shrub, not more than four or five feet high and about the same in width, gracefully hung with pale yellow flowers along the leafless twigs, March to April, a darling of prettiness. Corylopsis spicata is much the same, but grows rather taller, up to six feet, and is, if anything, more frost-resistant. They are not particular as to soil, but they do like a sheltered position, if you can give it them, say with a backing of other wind-breaking shrubs against the prevailing wind.

Deutzia longiflora – a classic late-spring flowering shrub that Vita loved.

‘Sparrows … peck the buds off, so put a bit of old fruit-netting over the plant in October or November when the buds are forming. Sparrows are doing the same to my Winter-Sweet this year [1952], as never before; sheer mischief; an avian form of juvenile delinquency; so take the hint and protect the buds with netting before it is too late.’

She also liked Halesia carolina, the snowdrop tree, and was given one by a friend. As with lots of her larger-scale plant presents, she planted it in the Orchard where it did well for years, but it has now succumbed to honey fungus. (A new one has recently been planted by the South Cottage back door). ‘This is a very pretty flowering tree, seldom seen; it is hung with white, bell-shaped blossoms, among pale green leaves, all along the branches. It can be grown as a bush in the open, or trained against a wall. There is a better version of it called Halesia monticola, but if you cannot obtain this from your nurseryman Halesia Carolina will do as well.’

For later in the spring, as well as deutzias and kolkwitzias Vita grew dipeltas, their branches all packed thickly with blossom. She had a deutzia in the Rose Garden and one in the White Garden in the early days, which she could use for picking. As she says, they need a sheltered spot or their blossom may brown in a late frost overnight, just as it’s emerging. They are ‘graceful and arching, May–June flowerers, four to six feet, ideal for the small garden where space is a consideration. They are easy, not even resenting a little lime in the soil, but beware of pruning them if you do not wish to lose the next year’s bloom. The most you should do is to cut off the faded sprays and, naturally, take out any dead wood. The only thing to be said against them is that a late frost will damage the flower, and that is a risk which can well be taken. Deutzia gracilis rosea, rosy as its name implies; D. pulchra, white; D. scabra Pride of Rochester, pinkish white, rather taller, should make a pretty group. They are not very expensive.’

This flowered at much the same time as Kolkwitzia amabilis and Dipelta floribunda, which Vita kept in a duo together in the Rose Garden: ‘two very pretty May–June flowering shrubs not difficult to grow, but for some reason not very commonly seen. They go well together, both being of the same shade of a delicate shell-pink and both belonging to the same botanical family (Caprifoliaceae), which includes the more familiar Weigelas and the honeysuckles, with small trumpet-shaped flowers dangling from graceful sprays.

‘Kolkwitzia comes into flower a little later than Dipelta, and thus provides a useful succession in the same colouring; in other words, a combination of the two would ensure a cloud of pale pink over a considerable number of weeks. It ought to be planted in front of the Dipelta, as it tends to make a more rounded bush, whereas the Dipelta grows taller and looser, and flops enough to require a few tall stakes. Both come from China, and each deserves the other’s adjective, as well as their own, for they are both amiable and floriferous.’ There are none now at Sissinghurst but Troy, the head gardener, is thinking of reinstating a Kolkwitzia somewhere.

SUMMER

Vita’s favourite summer-flowering shrubs were undoubtedly roses. She was famously passionate about the old-fashioned Gallica, Bourbon and Moss types, as well as a few elegant and larger-growing species and varieties, among them Rosa moyesii (see here) and its descendant ‘Nevada’. Writing about the old-fashioned roses, she says, ‘What incomparable lavishness they give … There is nothing scrimpy or stingy about them. They have a generosity which is as desirable in plants as in people.’ The joy of a rose, she goes on, is in a June or early July evening, ‘when for once in a while we are allowed a deep warm sloping sunlight; how rare and how precious [such evenings] are. They ought to be accompanied by fireflies, wild gold flakes in the air, but in this island we have to make do with tethered flowers instead. Amongst these, the huge lax bushes of the old roses must take an honoured place.’

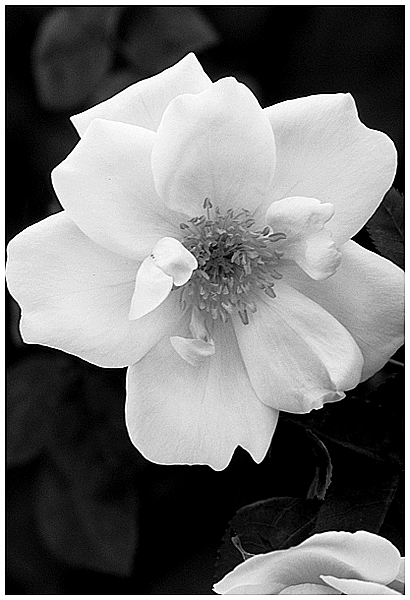

Rosa ‘Nevada’ photographed by Edwin Smith at Sissinghurst.

She loved roses, of course for their scent (see here), and climbing roses for draping the elegant Sissinghurst walls, but it was the shrub roses that Vita added in great numbers to her newly made Purple Border and Cottage Garden, and en masse to her Rose Garden. She had built up such a large collection since arriving at Sissinghurst, getting some from the old-fashioned rose specialist Edward Bunyard – as well as from Constance Spry and the nurserywoman Hilda Murrell, who helped her with the design and plant choice for the White Garden – that she’d outgrown her first rose garden, made outside the Priest’s House. Vita needed more space, and moved everything to a new site in what had been the vegetable garden on the southern edge of the garden.

Vita’s favourite roses were the ones with velvet textures to their petals and a richness and grandeur to their colours, roses that ‘swept me quite unexpectedly back to those dusky mysterious hours in an Oriental storehouse,’ she remembers, ‘where the rugs and carpets of Isfahan and Bokhara and Samarkand were unrolled in their dim but sumptuous colouring and richness of texture for our slow delight. Rich they were, rich as a fig broken open, soft as a ripened peach, flecked as an apricot, coral as a pomegranate, bloomy as a bunch of grapes. It is of these that the old roses remind me.’

Those old-fashioned shrub roses, ‘the Gallicas, the Damasks, the Centifolias or Cabbage, the Musks, the China, the Rose of Provins … all more romantic the one than the other’, had a deep glamour, a fading grandeur, just like all the favourite plants she chose and just like her interiors – her writing room and her bedroom. They were ‘the gipsies of the rose-tribe. They resent restraint; they like to express themselves in all their vigour freely as the fancy takes them, free as the dog-rose in the hedgerows. I know they are not to everybody’s taste, and I know that it isn’t everybody who has room for them in a small garden, but all the same I love them much and would sacrifice much space to them.’

Vita hated Hybrid Teas, and was not keen on most of the Hybrid Perpetuals, except for one or two such as ‘Ulrich Brunner’ (see here). She felt the new varieties lacked ‘the subtlety to be found in some of these traditional roses which might well be picked off a medieval tapestry or a piece of Stuart needlework. Indeed, I think you should approach them as though they were textiles rather than flowers. The velvet vermilion of petals, the stamens of quivering gold, the slaty purple of Cardinal Richelieu, the loose dark red and gold of Alain Blanchard; I could go on for ever, but always I should come back to the idea of embroidery and of velvet and of the damask with which some of them share their name. They have a quality of their own.

‘They usually smell better than their modern successors,’ she went on. ‘People complain that the modern rose has lost in smell what it has gained in other ways, and although their accusation is not always justified there is still a good deal of truth in it. No such charge can be brought against the Musk, the Cabbage, the Damask, or the Moss. They load the air with the true rose scent … Have I pleaded in vain?

Roses underplanted with bearded iris in Vita’s Rose Garden during the war.

‘This charm may be partly sentimental, and certainly there are several things to be said against the old roses: their flowering time is short; they are untidy growers, difficult to stake or to keep in order; they demand hours of snipping if we are to keep them free from dead and dying heads, as we must do if they are to display their full beauty unmarred by a mass of brown, sodden petals. But in spite of these drawbacks a collection of the old roses gives a great and increasing pleasure. As in one’s friends, one learns to overlook their faults and love their virtues.’

Roses gave Vita the all-important masses in the mixed borders, as well as being the glorious high point in her new Rose Garden. Created in 1937, this looked good almost straight away, and Vita managed to maintain it herself, with the help of one gardener and the occasional pruning skills of Harold, right through the war. The garden was so jam-packed that by 1959 – when Pam and Sybille arrived – if one rose bush failed from poor health or old age, they didn’t bother to replace it. They were sure that a bit more air in between the plants would do them good.

At its peak, on a late June evening in the Rose Garden, you still feel like you’ve walked into a bowl of potpourri – or not quite potpourri because it’s something fresher, juicier and more vegetable than that. From the flat severity of the York stone paths roses undulate in every direction, some tall and columnar, others quiet and petite, with the odd massive virtual tents of flowers – three bushes trained into one. They are all in full bloom at much the same time, and particularly at dawn and dusk, when there’s greater moisture in the air, their abundance and scent stop you dead.

That’s just what Vita wanted.

VITA’S TOP SHRUB ROSES

‘Drunk on roses, I look round and wonder which to recommend.’

Rosa alba ‘Great Maiden’s Blush’

Vita writes: ‘[Rosa alba] sounds as though it were invariably a white rose. Make no mistake. The adjective is misleading … the alba roses include many forms which are not white but pink … Great Maiden’s Blush [is] a very pretty and innocent-looking pink and white debutante … she holds her flowers longer than most. This is a very beautiful old rose, many-petalled, of an exquisite shell-pink clustering among the grey-green foliage, extremely sweet-scented, and for every reason perfect for filling a squat bowl indoors. In the garden she is not squat at all, growing 6 to 7 ft high and wide in proportion, thus demanding a good deal of room, perhaps too much in a small border but lovely and reliable to fill a stray corner … The albas … tolerate difficult situations, thriving in soil penetrated by the roots of trees (such as in woodland walks); they are resistant to mildew; and they can either be pruned or left un-pruned, according to the taste of the grower, the space available, and the time that can be devoted to them.’

Rosa gallica ‘Complicata’

This rose, as Vita says in More for Your Garden, has a ‘graceful untidiness’, which is just what Vita’s style is all about. It’s ‘a perfect rose-pink’ with ‘enormous single flowers borne all the length of the very long sprays. I cannot think why it should be called complicata, for it has a simplicity and purity of line which might come straight out of a Chinese drawing. This is a real treasure, if you can give it room to toss itself about as it likes; and whether you lightly stake it upright or allow it to trail must depend upon how you feel about it. Personally I think that its graceful untidiness is part of its charm, but whatever you do with it you can depend upon it to fill any corner with its renewed surprise in June.’ There is still a Rosa complicata in the garden, and more are being added.

Rosa ‘Complicata’.

Rosa ‘Grandmaster’

This one is a ‘hybrid musk … which would associate well as a bush planted in front of either Lawrence Johnstone or Le Rêve [see climbers, p. 000]. This is an exquisite thing, a great improvement on the other hybrid musk, Buff Beauty, though that in all conscience is lovely enough. Grandmaster is nearly single, salmon-coloured on the outside and a very pale gold within, scentless, alas, which one does not expect of a musk, but that fault must be overlooked for the extreme beauty of the bush spattered all over as it were with large golden butterflies. These shrubby roses are invaluable, giving so little trouble and filling so wide an area at so little cost.’

This is a very important rose at Sissinghurst, and one that Vita picked out to write about in Some Flowers. She used it to extend the colour in her Purple Border out from blue and purple and towards some rich pinks and dusky reds, including this one. There are two plants in the Top Courtyard, both put there by Vita and still healthy and vigorous growers. That’s a pretty good testament to this species.

‘This is a Chinese rose, and looks it,’ she writes. ‘If ever a plant reflected all that we had ever felt about the delicacy, lyricism, and design of a Chinese drawing, Rosa Moyesii is that plant. We might well expect to meet her on a Chinese printed paper-lining to a tea-chest of the time of Charles II, when wall-papers first came to England, with a green parrot out of all proportion, perching on her slender branches. There would be no need for the artist to stylise her, for Nature has already stylised her enough. Instead, we meet her more often springing out of our English lawns, or overhanging our English streams, yet Rosa Moyesii remains for ever China. With that strange adaptability of true genius she never looks out of place. She adapts herself as happily to cosy England as to the rocks and highlands of Asia.

‘“Go, lovely rose.” She goes indeed, and quickly. Three weeks at most sees her through her yearly explosion of beauty. But her beauty is such that she must be grown for the sake of those three weeks in June. During that time her branches will tumble with the large, single, rose-red flower of her being. It is of an indescribable colour. I hold a flower of it here in my hand now, and find myself defeated in description. It is like the colour I imagine Petra to be, if one caught it at just the right moment of sunset. It is like some colours in a rug from Isfahan. It is like the dyed leather sheath of an Arab knife – and this I do know for certain, for I am matching one against the other, the dagger-sheath against the flower. [This knife is still in Vita’s desk drawer.] It is like all those dusky rose-red things which abide in the mind as a part of the world of escape and romance.

‘Then even when the flowers are gone the great graceful branches are sufficiently lovely in themselves. Consider that within three or four years a single bush will grow some twelve feet high and will cover an area six to eight feet wide; long waving wands of leaves delicately set and of an exquisite pattern, detaching themselves against the sky or the hedge or the wall, wherever you happen to have set it. Never make the mistake of trying to train it tight against a wall: it likes to grow free, and to throw itself loosely into the fountains of perfect shape it knows so well how to achieve. Do not, by the way, make the mistake either of industriously cutting off the dead heads, in the hope of inducing a second flowering. You will not get your second flowering and you will only deprive yourself of the second crop which it is preparing to give you: the crop of long bottle-shaped, scarlet hips of the autumn. Preserve them at all costs, these sealing-wax fruits which will hang brighter than the berries of the holly … We already have the variety called Geranium, of stockier growth, and the beautiful white Nevada, which is not a chance seedling but a deliberate cross.’

Rosa mundi (correctly, R. gallica ‘Versicolor’)

This is still grown, lightly staked, in the Rose Garden.

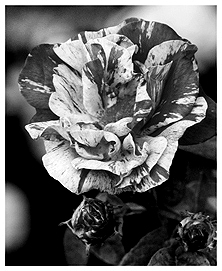

‘Striped and splotched and blotted,’ Vita writes again in Some Flowers, ‘this fine old rose explodes into florescence in June, giving endless variations of her markings. You never know what form these markings are going to take. Sometimes they come in red orderly stripes, sometimes in splashes, sometimes in mere stains and splotches, but always various, decorative, and interesting. They remind one of red cherry juice generously stirred into a bowl of cream. A bush of Rosa Mundi in full flowering is worth looking at. It is not worth cutting for the house unless you have the leisure to renew your flower-vases every day, for in water it will not last. Even out of doors, blooming on its own bush, it does not last for very long. It is a short-lived delight, but during the short period of its blooming it makes up in quantity what it lacks in durability …

Rosa gallica ‘Versicolor’.

‘Perhaps all the foregoing makes it sound rather unsatisfactory and not worthwhile. On the contrary, it is very much worthwhile indeed. For one thing, you can stick it in any odd corner, and indeed you will be wise to do so, unless you have a huge garden where you can afford blank gaps during a large part of the year. You can also grow it as a hedge, and let it ramp away.

‘A word as to pruning … Rosa Mundi needs all weak shoots to be cut out after the flowering time is over, and in the spring the remaining shoots should be shortened to within half a dozen buds.’

Rosa ‘Mutabilis’, or Rosa ‘Turkestanica’

Mutabilis means ‘liable to change’ in Latin, a characteristic of this rose, which opens pink and gradually fades to a sort of apricot. You’ll see both colours on a bush at one time. As with many of the China roses (such as ‘Comtesse du Cayla’, which Vita also loved and picked for the house (see here)), this flowers lightly for almost six months. It’s hugely useful and looks wonderful against red brick. In August 1952 Vita writes: ‘This makes an amusing bush, five to six feet high and correspondingly wide, covered throughout the summer with single flowers in different colours, yellow, dusky red, and coppery, all out at the same time. It is perhaps a trifle tender, and thus a sheltered corner will suit this particular harlequin.’

Rosa ‘Nevada’

This was one of Vita’s favourite roses which she had planted right at the edge of the path in Delos, so she could see it with the Tower standing behind it in the background.

‘This is not a climber,’ she notes in In Your Garden, ‘but a shrubby type, forming an arching bush up to seven or eight feet in height, smothered with great single white flowers with a centre of golden stamens. One of its parents was the Chinese species rose Moyesii, which created a sensation when it first appeared and has now become well known … The grievance against Moyesii is that it flowers only once, in June; but Nevada, unlike Moyesii, has the advantage of flowering at least twice during the summer, in June and again in August, with an extra trickle of odd flowers right into the autumn. One becomes confused among the multitude of roses, I know, but Nevada is really so magnificent that you cannot afford to overlook her. A snowstorm in summer, as her name implies. And so little bother. No pruning; no staking; no tying. And nearly as thornless as dear old Zéphyrine Drouhin. No scent, I am afraid; she is for the eye, not for the nose.’

Rosa ‘Tuscany’

‘Tuscany’ is the epitome of the sort of rose that Vita delighted in. It’s plush velvet in all its parts – it has deep crimson petals with a whorl of golden anthers at their heart, and a sweet, intense, classic rose perfume. It’s quite a healthy rose too – I’ve had it in my organic rose trial in a partially shaded spot now for five years, and it does not get blackspot. There are still several bushes of this in the Rose Garden.

‘Tuscany opens flat (being only semi-double),’ Vita says, ‘thus revealing the quivering and dusty gold of its central perfection … It is more like the heraldic Tudor rose than any other. The petals, of the darkest crimson, curl slightly inwards and the anthers, which are of a rich yellow, shiver and jingle loosely together if one shakes the flower.

‘The velvet rose. What a combination of words! One almost suffocates in their soft depths, as though one sank into a bed of rose-petals, all thorns ideally stripped away. No photograph can give any idea of what it is really like. Photographs make it look merely funereal – too black, almost a study in widow’s crêpe. They make the flower and the leaf appear both of the same dark colour, which is unfair to so exquisite a thing.

‘As like Rosa Mundi, Tuscany is a Gallica, it needs the same kind of pruning; it will never make a very tall bush, and your effort should be to keep it shapely – not a very easy task, for it tends to grow spindly shoots, which must be rigorously cut out. Humus and potash benefit the flowers and the leaves respectively.’

Rosa ‘William Lobb’ – the Moss rose

Another classic Vita rose with extraordinary colouring – properly purple, then fading a little like a tapestry or embroidered cushion. It also has excellent scent:

‘As they reach the stage where some of the flowers are passing while others are still coming out, they look as though some rich ecclesiastical vestment had been flung over them. The dull carnation of the fresh flowers accords so perfectly with the slaty lilac of the old, and the bunches cluster in such profusion, that the whole bush becomes a cloth of colour, sumptuous, as though stained with blood and wine. If they are to be grown in a border, I think they should be given some grey-leaved plant in front of them, such as Stachys lanata (more familiarly, Rabbits’ Ears), for the soft grey accentuates their own musty hues, but ideally speaking, I should like to see a small paved garden with grey stone walls given up to them entirely, with perhaps a dash of the old rose prettily called Veilchenblau (violet-blue) climbing the walls and a few clumps of the crimson clove carnation at their feet.’

Rosa ‘Ulrich Brunner’

In Vita’s view this is one of the best Hybrid Perpetuals, useful for prolonging the season and lasting well in water. It was one of the first roses the gardener Jack Vass experimented on with his new rose-training technique (see here). ‘Ulrich Brunner’ is ‘stiff-stemmed, almost thornless, cherry-red in colour, very prolific indeed, a real cut-and-come-again … Ulrich Brunner, Frau Karl Druschki, and the Dicksons, Hugh and George, are very suitable for this kind of training. The hybrid perpetuals can also be used as wall plants; not nearly so tall as true climbers and ramblers, they are quite tall enough for, say, a space under a ground floor window; or they may be grown on post-and-wire as espaliers outlining a path.’

TRAINING SHRUB ROSES

What looks like unbridled profusion in the Sissinghurst roses relies on meticulous work behind the scenes early in the year, when precision horticulture guarantees that wonderful romantic effect. It’s well worth visiting the garden at the beginning of the growing season, when the bare bones – the beautiful, intricate webs of rose stems without their leaves – are clearly visible, so you can see how the gardeners do it. This rose-training system originated at Cliveden in Buckinghamshire with the Astors’ head gardener Jack Vass, who moved to Sissinghurst in 1939. Other National Trust properties now send their gardeners to Sissinghurst to learn the ingenious technique. We know how devoted Vita was to her roses, but it was Jack Vass who started to grow them in this exceptional way.

Shrub roses trained on to hazel benders, in the characteristic Sissinghurst way.

All roses can be encouraged to produce more flowering side-shoots if their stems are trained as nearly horizontal as possible. If you put every stem of a rose plant under pressure, bending and stressing it, the rose will flower more prolifically. The plant’s biochemistry is telling the bush it’s on its way out and so needs to make as many flowers as possible.

They should be pruned before they come into leaf to prevent leaf buds and shoots from being damaged as their stems are manipulated, so do this in the winter or early spring. Depending on their habit, shrub roses are trained in one of three ways.

First, the tall, rangy bushes with stiffer branches – such as ‘Charles de Mills’, ‘Ispahan’, ‘Gloire de France’, ‘Cardinal de Richelieu’ and ‘Camayeux’ – are twirled up a frame of four chestnut or hazel poles. Every pruned tip is bent and attached to a length below.

Second, the big leggy shrubs, which put out great, pliable, triffid arms that are easy to tie down and train, are bent on to hazel hoops arranged around the skirts of the plant. Roses with this lax habit include ‘Constance Spry’, ‘Fantin-Latour’, ‘Zéphirine Drouhin’, ‘Madame Isaac Pereire’, ‘Coupe d’Hébé’, ‘Henri Martin’ and ‘Souvenir du Docteur Jamain’.

In Even More for Your Garden, Vita comments in September 1957: ‘These strong growers lend themselves to various ways of treatment. They can be left to reach their free height of 7 to 8 ft., but then they wobble about over eye-level and you can’t see them properly, with the sun in your eyes, also they get shaken by summer gales. A better but more laborious system is to tie them down to benders, by which I mean flexible wands of hazel with each end poked firmly into the ground and the rose-shoots tied down at intervals, making a sort of half-hoop. This entails a lot of time and trouble, but is satisfactory if you can do it; also it means that the rose breaks at each joint, so that you get a very generous floraison, a lovely word I should like to see imported from the French into our language. If you decide to grow hybrid perpetuals on this system of pegging them down, you ought to feed them richly, with organic manure if you can get it, or with compost if you make it, but anyhow with something that will compensate for the tremendous effort they will put out from being encouraged to break all along their shoots. You can’t ask everything of a plant, any more than you can exact everything of a human being, without giving some reward in return. Even the performing seal gets an extra herring.’

Under Pam and Sybille the technique was refined. All the old and diseased wood is removed and then, stem by stem, last year’s wood is bent over and tied onto the hazel hoop. You start at the outside of the plant and tie that in first, then move towards the middle, using the plant’s own branches to build up the web and – in the case of ‘Constance Spry’ and ‘Henri Martin’ – create a fantastic height, one layer domed and attached to the one below. Without any sign of a flower, this looks magnificent as soon as it’s complete, and in a couple of months each stem, curved almost to ground level, will flower abundantly.

The third method of training shrub roses applies to the contained, well behaved, less prolific varieties (‘Petite de Hollande’, ‘Madame Knorr’, ‘Chapeau de Napoléon’ (or Rosa × centifolia ‘Cristata’) and those that produce branches too stiff to bend (‘Felicia’ and the newish David Austin rose, ‘William Shakespeare 2000’), and these are tackled slightly differently. They are pruned hard, then each bush is attached with twine to a single stake cut to about the height of the pruned bush. Without the stake, even these would topple under the weight of their summer growth.

OTHER SUMMER-FLOWERING SHRUBS

Roses were the dominant flowering shrubs for Vita’s summer garden, and rightly so, but she had a few other beauties, good recommendations still worth taking seriously today.

In her new White Garden she planted the huge, crinkly white-bloomed romneya, or Californian tree poppy, a flowering but not woody shrub, more like an evergreen perennial – and it’s still there. It takes a while to get established, but after three or four years will flower prolifically and will last for decades. My mother grows lots of it in her garden outside Cambridge and it’s been there now for almost fifty years. Vita describes it in In Your Garden:

‘A beautiful thing in flower in July is the Californian tree-poppy. It is not exactly an herbaceous plant; you can call it a sub-shrub if you like; whatever you call it will make no difference to its beauty.

‘With grey-green glaucous leaves, it produces its wide, loose, white-and-gold flowers on slender stems five or six feet in height. The petals are like crumpled tissue paper; the anthers quiver in a golden swarm at the centre. It is very lovely and delicate.

‘I don’t mean delicate as to its constitution, except perhaps in very bleak districts. Once you get it established it will run about all over the place, being what is known as a root-runner, and may even come up in such unlikely and undesirable positions as the middle of a path. I know one which has wriggled its way under a brick wall and come up manfully on the other side. The initial difficulty is to get it established, because it hates being disturbed and transplanted, and the best way to cheat it of this reluctance is to grow it from root cuttings in pots. This will entail begging a root cutting from a friend or an obliging nurseryman. You can then tip it out of its pot into a complaisant hole in the place where you want it to grow, and hope that it will not notice what has happened to it. Plants, poor innocents, are easily deceived …

Romneya coulteri.

‘It likes a sunny place and not too rich a soil. It will get cut down in winter most likely, but this does not matter, because it will spring up again, and in any case it does not appear to flower on the old wood, so the previous season’s growth is no loss. In fact, you will probably find it advisable to cut it down yourself in the spring, if the winter frosts have not already done it for you.’

She offers another suggestion:

‘A good companion to the tree-poppy is the tall, twelve-foot shrub which keeps on changing its name. When I first knew and grew it, it called itself Plagianthus Lyallii. Now it prefers to call itself Hoheria lanceolata [now correctly called Hoheria lyalli (see following page)]. Let it, for all I care. So far as I am concerned, it is the thing to grow behind the tree-poppy, which it will out-top and will complement with the same colouring of the pale green leaves and the smaller white flowers, in a candid white and green and gold bridal effect more suitable, one would think, to April than to July. Doubts have been cast upon its hardiness, but I have one here (in Kent) which has weathered a particularly draughty corner where, in optimistic ignorance, I planted it years ago. There is no denying, however, that it is happier with some shelter by a wall or a hedge.’

Hoheria lyallii has ivory-coloured flowers, beautiful singles like one of the Japanese cherries, only each flower is almost twice the size. They feel like spring blossom but come in summer, their flowers a fine contrast to their bright apple-green leaves. There’s almost no lovelier jug of flowers to have in a great cloud at the end of summer. As Vita says, ‘I can’t think why people don’t grow Hoheria lyallii often, if they have a sheltered corner and want a tall 10-ft. shrub that flowers in that awkward time between late June and early July, smothered in white-and-gold flowers of the mallow family, to which the hollyhock also belongs, and sows itself in such profusion that you could have a whole forest of it if you had the leisure to prick out the seedlings and the space to replant them.

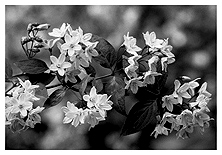

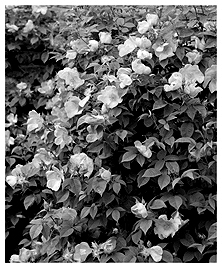

Hoheria lyalii, one of Vita’s favourite summer shrubs with beautiful saucer-like flowers, similar to cherry blossom.

‘It really is a lovely thing, astonishing me every year with its profusion. I forget about it; and then there it is again with its flowers coming in their masses suggesting philadelphus, for which it might easily be mistaken, but even more comely than any philadelphus, I think, thanks to the far prettier and paler leaf.

‘It has other advantages. It doesn’t dislike a limy soil, always an important consideration for people who garden on chalk and can’t grow any of the lime-haters. It doesn’t like rich feeding, which tends to make it produce leaf rather than flower. This means an economy in compost or organic manures or inorganic fertilizers which could be better expended elsewhere. Bees love it. It is busy with bees, making their midsummer noise as you pass by.’

She also loved the ‘false acacia’, Robinia pseudoacacia, another small tree which was – and still is – little grown in England. She would have come across it, as she says, in her travels to the Mediterranean, where it’s still a common tree lining many small squares and side streets. It’s a delicate, fine-looking thing which does not throw too much shade, so it’s ideal for a small country or town garden and its flowers have a delicious orange blossom scent. In France they dip them in batter and serve them – scattered with sugar – as a pudding.

These trees ‘abound in France and Italy,’ she remarks, ‘but are equally at home with us. There are few summer-flowering trees prettier than they, when they hang out their pale, sweet-scented tassels, and few faster of growth for people in a hurry. I have planted them no taller than a walking-stick, and within a contemptible number of years they have taken on the semblance of an established inhabitant, with sizeable trunks and a rugged bark and a spreading head, graceful and fringy. If they have a fault, it is that their boughs are brittle, that they make a good deal of dead wood, and, I suspect, are not very long-lived, especially if the main trunk has forked, splitting the tree into halves. This danger can be forestalled by allowing only one stem to grow up, with no subsidiary lower branches.

‘If, after reading this cautionary tale, you still decide to plant an acacia, let me suggest that you might try not only the ordinary white-flowered one, but also the lovely pink one, Robinia hispida, the rose acacia. It is no more expensive to buy than the white, and is something less often seen, a surprise to people who expect white flowers and suddenly see pink. Robinia kelseyi is another rose-pink form much to be recommended.’

There is now a fully grown fifty-foot tree on the edge of the Cottage Garden as it borders the Nuttery – which, despite what she says above about it being short-lived, has lasted the eighty-odd years since she planted it. This perfumes the entire Cottage Garden in May and June and you can hear the whole tree buzzing with pollinators.

Also discovered on her French travels, she loved the chintz-flower looks of Hibiscus syriacus, also known as Althea frutex, but you need to find it a sheltered sunny spot to ensure it flowers well. I grow this in a pot in my cold greenhouse. It is one of ‘the tree hollyhocks, which you can get with blue flowers, or claret coloured, or white, or mauve,’ she tells her readers. ‘I like especially the white form with purple blotch at the base, reminiscent of a Victorian chintz, and, moreover, it seems to give more generously of its flowers than the blue and the red varieties. They flower in August and have the advantage of living to a great age, for I remember seeing one in south-western France with a trunk the size of a young oak. Its owner assured me that it had been in her garden for over a hundred years. “Mais bien sûr, madame, c’est mon arrière-grand-père qui l’a planté.” It had been trained as a standard, with a great rounded head smothered in flowers.’

Her final must-have for August is Tamarix pentandra, the ‘summer-flowering tamarisk which flowers … during that month when flowering shrubs are few. We do not grow the tamarisks enough; they are so graceful, so light and buoyant, so feathery, so pretty when smothered in their rose-pink flower. The earlier-flowering one is Tamarix tetrandra; comes out in April to May.’

AUTUMN

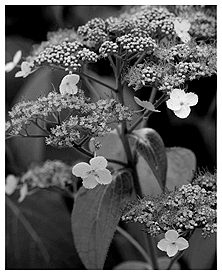

Vita did not at first plant many hydrangeas at Sissinghurst. She had the climber Hydrangea petiolaris on one of the east-facing walls, but at least initially she had reservations about them – the coarser ones reminded her of ‘coloured wigs’. She probably associated them with rather more formal Edwardian borders, a look she was trying to avoid, but seeing them in other people’s gardens looking good, she began to like them more.

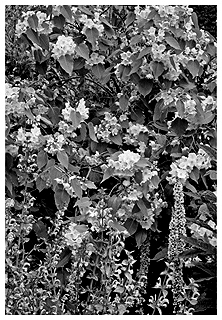

‘I really prefer the looser kinds called paniculata,’ she writes, ‘which have a flat central head fringed by open sterile flowers; a particularly pleasing variety is called Sargentii. Another good one is Hydrangea paniculata grandiflora. It was with a startled pleasure that I observed three bushes growing in a cottage garden as I drove along a secret lane. They looked like pink lilac. Tall, pyramidal in shape, smothered in pointed panicles of flower, they suggested a bush of pink lilac in May. Yet this was September … Puzzled, I stopped by the roadside to investigate.

‘It was Hydrangea paniculata grandiflora, sometimes called the plumed hydrangea. In its native country, Japan, it is said to attain a height of twenty-five feet, but in this country it apparently limits itself to something between six and eight feet; and quite enough, too, for the average garden. Do not confuse it with H. hortensis, the one which sometimes comes sky-blue but more often a dirty pink, and which is the one usually seen banked up in Edwardian opulence against the grandstand of our more fashionable race-courses. H. paniculata grandiflora, in spite of its resounding name, is less offensively sumptuous and has a far subtler personality.

‘It reveals, for instance, a sense of humour, and even of fantasy in the colouring it adopts throughout its various stages. It starts off by flowering white; then turns into the pink I have already described as looking like pink lilac. Then it turns greenish, a sort of sea-green, so you never know where you are with it, as you never know where you are with some human personalities, but that makes them all the more interesting. Candidly white one moment; prettily pink the next; and virulently green in the last resort … As I was leaning over the gate, looking at this last pink-green inflorescence, the tenant of the cottage observed me and came up. Yes, he said, it has been in flower for the last three months. It changes its colour as the months go by, he said.’

There have been lots of new varieties of H. paniculata since Vita’s day and they are much underrated – widely grown in France and Germany, but little known here. They are big (about three feet by three feet if pruned), but not too big, so go well at the back of a herbaceous border, or underplanting and interlinking with taller shrubs. They are also excellent at an entrance or as a marker at the beginning or end of a bed, and are particularly lovely mixed with shrubs with variegated leaves. They look good throughout the summer, reach their flowery peak in the autumn and have good winter interest, only needing to be cut back in March or April.

I particularly like Hydrangea paniculata ‘Limelight’. This opens the cleanest, brightest, acid green, with a brilliant architectural chiselled flower form, unfurling to cups in a green-washed cream. Then the flowers fully flatten and turn pure ivory, before being washed with rich pink, the last stage before they gracefully brown and dry on the stem. It’s an amazing succession which lasts from August until January, or even longer if the flowers are not thrashed around too much by the wind and rain.

‘Hydrangea aspera ‘Kawakamii’ group.

Vita goes on to say: ‘Hydrangea aspera is good too and there are some decorative forms called villosa and Sargentiana. A bush, pouring over a paved path or covering the angle of a flight of steps, is a rich and rewarding sight in August, when everything becomes heavy and dark and lumpish.’ It’s true – any H. aspera is gorgeous, but a newly found form called ‘Kawakamii’, in particular, is an amazing performer. It has no sensitivity to pH, so its flowers keep their lovely colour whatever the profile of your soil. It goes on flowering very long and late, retaining its delicate beauty and wonderful overall shape. With just one plant you get a complex multi-storey effect, perfect for filling a corner in any partly shaded place. The only problem with hydrangeas is that none of them do well in a drought.

Vita planted several indigoferas, still little known and grown but even rarer then, and there are still a couple in the garden. These are all, as Vita puts it, ‘graceful shrubs which should be more freely planted. They throw out long sprays, seven or eight feet in length, dangling with pinkish, vetch-like flowers in August and September all along the tall, curving sprays. Like the fuchsias, they will probably get cut down in frosty weather, but this does not matter, because in any case you should prune them to the ground in April, when, like the fuchsias, they will shoot up again. They thrive at the foot of a south wall. There are several varieties, all desirable: Gerardiana, Potaninii, and Pendula … Indigofera Potaninii is a pale, pretty pink; I. Gerardiana is deeper in colour, with more mauve in it, and is perhaps the more showy of the two. They should both, I think, be planted in conjunction, so that their sprays can mingle in a cloud of the two different colours … I must end by urging you to grow Indigofera pendula. This is a surprisingly lovely thing. It arches in long sprays of pinkish-mauve pea-like flowers, growing ten feet high, dangling very gracefully from its delicate foliage.’

Indigofera pendula.

Nick Macer, the plant collector and discerning nurseryman at Pan-Global in Gloucestershire, names Indigofera pendula as one of his favourite plants. When I saw it in his garden he had self-sown Verbena bonariensis growing up through it, vertical purple spires from below, with a lovely white climbing Cobaea pringlei draped from above. It made a brilliant combination.

As the autumn goes on, flowering shrubs become almost nonexistent, bar the stalwart fuchsia brigade. Anyone who wants at least a bit of colour in their October and November garden would be mad not to include some of these. There are stacks of new hybrids with complicated tiered rah-rah skirts in zingy contrasting colours, but I don’t think these would be Vita’s thing.

She quite rightly tells us there are some fuchsias much hardier than we think: ‘It is quite unnecessary to associate them only with Cornwall, Devon and the west coast of Scotland. Several varieties will flourish in any reasonably favourable county, and although they will probably be cut to the ground by frost in winter, there is no cause for alarm, for they will spring up again from the base in time to flower generously in midsummer and right the way through the autumn. As an extra precaution, the central clump or crown can be covered with dry leaves, bracken, or soil drawn up to a depth of three or four inches; and in case of extremely hard weather an old sack can temporarily be thrown over them. Their arching sprays are graceful; I like the ecclesiastical effect of their red and purple amongst the dark green of their foliage; and, of course, when you have nothing else to do you can go round popping the buds.

‘The most familiar is probably Fuchsia magellanica Riccartonii, which will flower from July to October. F. gracilis I like less; it is a spindly-looking thing, and F. magellanica Thompsonii is a better version of it. F. Mrs. Popple, cherry-red and violet; Mme Cornelissen, red and white; and Margaret, red and violet, are all to be recommended.

‘They … like a sunny place in rather rich soil with good drainage. You can increase them by cuttings inserted under a hand-light [a glass cloche] or a frame in spring.’

Vita’s final recommendation, not for their flowers but for their seedpods and brilliant autumn leaves, are the coluteas, plants that many people are snooty about, feeling they’re common as muck and not worth growing.

Often anti-snob about these things, Vita had a line in such garden plants, and she was keen on these particular ones. My parents – possibly under her influence – also grew one of the coluteas, and as a child I loved popping the swollen banana-shaped seedpods, blown up taut like a balloon. Here’s what Vita says about them:

‘Two shrubs or little trees with an amazingly long flowering period – Colutea arborescens and Colutea media, the Bladder Sennas. They have been flowering profusely for most of the summer, and were still very decorative in the middle of October. Of the two I prefer the latter. C. arborescens has yellow flowers; but although media (with bronze flowers) is perhaps the more showy, they go very prettily together, seeming to complement one another in their different colouring. Graceful of growth with their long sprays of acacia-like foliage, amusingly hung with the bladders of seed-pods looking as though they would pop with a small bang, like a blown-up paper bag, if you burst them between your hands … which give them their English name, the bright small flowers suggest swarms of winged insects. C. arborescens amuses me, because it carries its flowers and its seed-pods at the same time. In one garden where I saw it the pods were turning pink, very pretty amongst the flowers.

‘They are of the easiest possible cultivation, doing best in a sunny place, and having a particular value in that they may be used to clothe a dry bank where few other things would thrive, nor do they object to an impoverished stony soil. They are easy to propagate, either by cuttings or by seed, and they may be kept shapely by pruning in February, within a couple of inches of the old wood.

‘I know that highbrow gardeners do not consider them as very choice. Does that matter? To my mind they are delicately elegant, and anything which will keep on blooming right into mid-October has my gratitude.

‘By the way, they are not the kind of which you can make senna-tea. Children may thus regard them without suspicion and will need little encouragement to pop the seedpods. It is as satisfactory as popping fuchsias.’

PLACING AND PRUNING

The shrubs and roses were often placed right by the path, rather than further back in the border, and then minimally and loosely pruned – all contributing to the ‘cram, cram, cram’ of Vita’s garden look. This is one of the most noticeable things about the photographs of the early garden: within the yew hedges, or the brick-wall edges of the garden ‘rooms’, were living divisions, decorative curtains splitting the space into cosier corners, areas which would work on an intimate, human scale.

Vita wanted her garden to mimic a Dutch flower painting, as she wrote in The Land, like a ‘Dutchman’s canvas crammed to absurdity’.

Vita felt firmly that, once the massed plantings or large individual shrubs were well established, it was important to shape and prune them, but not too much. So as to be safe and not over-prune, she tells us in More for Your Garden, do this when they’re going at full tilt in the summer, not at normal pruning time in autumn or winter. ‘By this time of the year, most of our plants have grown into their full summer masses, and this is the moment when the discerning gardener goes round not only with his notebook but also with his secateurs and with that invaluable instrument on a pole 8 ft. long, terminated by a parrot’s beak, which will hook down and sever any unwanted twig as easily as crooking your finger.’ If you wait till winter, it’s difficult to see or remember the effect you want, and then it’s all too easy to wantonly hack away.

Plants in Vita’s borders, as Anne Scott-James writes, ‘are mixed with joyous informality and allowed freedom to grow naturally, with a minimum of stakes, secateurs and shears’. Some would say this tipped too far into messy chaos and I’m sure that’s true at times, but the art of ‘fine carelessness’ was Vita’s way. She was following a long tradition. Consider this quote describing a wedding masque in 1606: ‘The men were clad in Crimson, and the women in white. They had every one a white plume of the richest herons’ feathers, and were so rich in jewels upon their heads as was most glorious … As citizens of Arcadia, they had their hair “carelessly (but yet with more art than if more affected) bound under the circle of a rare and rich coronet”. Naturalness was virtue.’

It’s not naturalness, of course, but highly contrived art, an understanding that beauty lives on the border between the wild and the controlled. It’s just this sort of look that Vita was cultivating in her garden, a question of taking a risk, experimenting with something that might just be too much, but that also might give a kind of pleasure that the over-controlled can never even approach.

‘Fine carelessness’ is a carefully calibrated phrase. And it takes some doing.