9

PAINTERLY PLANTS

Vita planted swathes of bearded iris to line the stone paths, which flower to fill the colour gap between the bulbs in spring and the roses of early summer.

Vita was clear on her overall approach to designing her flower borders, and as to which were her favourites among the larger plants, the shrubs and climbers. Now to the more delicate things, the smaller plants she wanted to cram into her garden rooms so as to fill them to overbrimming.

In the early months of the year, she focused on the miniature flowers which weren’t yet squeezed out by the garden’s overall abundance; and she returns to this smaller scale in her plant choices for late autumn and winter. She sought out things which were, as she put it, ‘shy, unobtrusive, demure; this is the way I like my flowers to be; not puffed up as though by a pair of bellows; not shouting for praise from gaping admirers’. And as she wrote in Passenger to Teheran, published in 1926, about a trip she’d made to Iran to visit Harold who was at the embassy there, ‘I like my flowers small and delicate – the taste of all gardeners, as their discrimination increases, dwindles towards the microscopic.’ You can see that from the plants she wrote about with the most affection.

Vita was especially fond of painterly plants, ones less noticeable outside in the general garden brouhaha, but when they come inside you can revel in their intricate beauty, sitting right in front of you in a pot or vase: ‘The flowers I like best are the flowers requiring a close inspection before they consent to reveal their innermost secret beauty.’ She was on the lookout for plants with a Fabergé delicacy, markings as if by the brush of a Chinese calligrapher. Vita would always have a good selection around her, including one or two things miraculous and exquisite, detailed and refined. She had lots of bearded irises, their texture and scent often as good as their colour; and delicates such as species crocus, Iris reticulata, meadow fritillaries and Ixia viridiflora.

This was why she loved to grow things in containers as well as in the garden itself. Then you could see the intricate flowers more clearly. She made a series of miniature gardens in troughs and old sinks and kept a clutch of pots at the entrance to the garden and at the top of the Tower steps. She also had indoor pots in a cold greenhouse. In there, whatever the weather, she could grow a few precious items: lily-of-the-valley and sweet violets forced into flower early, and elegant show auriculas, salpiglossis and tender nerines, all out of the worst of the weather and so still pristine.

She picked flowers all the time – some sprigs from her great range of flowering shrubs like hamamelis, mahonias, hoheria and Magnolia grandiflora, or a little bunch of spring bulbs, miniature iris, anemones, grape hyacinths, fragrant tazetta narcissus, mixed in with violets and primroses. Her relationship with the plant did not, then, stop at a fleeting whisk past in the garden, but could continue inside as a long hard stare.

Best known as Vita is for her all-enveloping, voluptuous gardening style and for her single-colour garden rooms, when you looked more closely there would always have been a good proportion of plants possessing a precise and exquisite beauty – something for which she had a great eye. It’s these ideas – intricate plants for the garden and for pots both inside and out, plus lots of things for picking – that we can easily copy, whatever the size of our garden. We can fill our lives with the brilliance of Vita’s ideas, on the small scale if we can’t match the grand.

WINTER

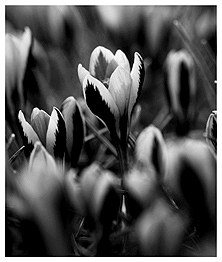

Vita liked to have crocuses to pick – just a few – to arrange in an eggcup, scent bottle or sherry glass inside. They’re one of the first markers that the dreary winter is nearly over and that spring is, thank goodness, on its way. My favourite variety is newly bred, so Vita wouldn’t have known it, but ‘Spring Beauty’ has all the delicacy and fineness of the ones she loved. ‘Advance’ and ‘Snow Bunting’ – which she mentions – are both splendid, forced in a pot or left to flower a little later in the garden, then admired or picked from there.

Crocus ‘Spring Beauty’.

Crocuses are easy to grow and get better and better every year. Each of the chrysanthus varieties will cross-breed and self-sow, gradually studding your grass till it looks like Boticelli’s Primavera. The best place to see this is in the late Christopher Lloyd’s lawns and meadows at Great Dixter, magnificent for early bulbs at the end of winter. It’s like walking into an Alpine meadow, but even better, distilled and heightened with all the best spring bulbs scattered through the grass. The chrysanthus varieties were Christopher’s favourites. As Fergus Garrett, the head gardener at Dixter, says, there isn’t an ugly one amongst them. There are many patches of ‘Snow Bunting’, deliciously scented, which clumps rather than spreads, with its pure white flowers and free-range-egg-yolk-yellow centres. If you follow Vita’s recommendations, you’ll have a succession flowering from January until the end of March. Here are some comments from In Your Garden Again, for February 1953:

‘I now find myself regretting that I did not plant more of the species crocuses which are busy coming out in quick succession. They are so very charming, and so very small. If you can go and see them in a nursery garden or at a flower show, do take the opportunity to make a choice. Grown in bowls or Alpine pans they are enchanting for the house; they recall those miniature works of art created by the great Russian artificer Fabergé in the luxurious days when the very rich could afford such extravagances. Grown in stone troughs out of doors, they look exquisitely in scale with their surroundings, since in open beds or even in pockets of a rockery they are apt to get lost in the vast areas of landscape beyond.

‘One wants to see them close to the eye, fully to appreciate the pencilling on the outside of the petals; it seems to have been drawn with a fine brush, perhaps wielded by some sure-handed Chinese calligrapher, feathering them in bronze or in lilac. Not the least charm of these little crocuses is their habit of throwing up several blooms to a stem (it is claimed for Ancyrensis that a score will grow from a single bulb). Just when you think they are going off, a fresh crop appears.

‘Ancyrensis, from Ankara and Asia Minor, yellow, is usually the first to flower in January or early February, closely followed by chrysanthus and its seedlings E. A. Bowles, yellow and brown; E. P. Bowles, a deeper yellow feathered with purple; Moonlight, sulphur yellow and cream; Snow Bunting, cream and lilac; Warley White, feathered with purple. That fine species, Imperati, from Naples and Calabria, is slightly larger, violet-blue and straw-coloured; it flowers in February. Susianus, February and March, is well known as the Cloth of Gold crocus; Sieberi, a Greek, lilac-blue, is also well known; but Suterianus and its seedling Jamie are less often seen. Jamie must be the tiniest of all: a pale violet with deeper markings on the outside, he is no more than the size of a shilling across when fully expanded, and two inches high. I measured.

‘I have mentioned only a few of this delightful family, which should, by the way, be planted in August.’

For the start of the year, Vita liked to have plenty of Iris reticulata in as many of its different forms as she could find. She planted enough so as to be able to admire their stalwartness out in the brutal February conditions, in the open borders or in one of her precious troughs (see here), as well as some in pots to bring inside. They are marvellous inside, but the flowers are transient in the heat.

Very persistent bulbs, their numbers grew more and more each year and you’ll still find lots at Sissinghurst, in the troughs in the Top Courtyard and popping up in patches in Delos and the Lime Walk. There are many forms, but I particularly love the luscious ruby-purple ‘Pauline’ (similar to ‘Hercules’ in Vita’s list below), the bluer-purple ‘Harmony’, as well as the bright mauve ‘Cantab’, which she also mentions. And add to these the red-purple silk velvet, Iris histrioides, ‘George’.

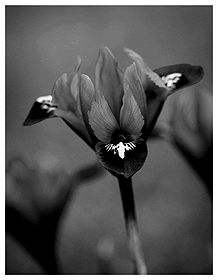

Iris reticulata ‘Rhapsody’.

Vita’s enthusiasm, as ever, is infectious:

‘It seems extraordinary that anything so gay, delicate, and brilliant should really prefer the rigours of winter to the amenities of spring. It is true that we can grow Iris reticulata in pots under glass if we wish to do so, and that the result will be extremely satisfying and pretty, but the far more pleasing virtue of Iris reticulata is that it will come into bloom out of doors as early as February, with no coddling or forcing at all. Purple flecked with gold, it will open its buds even above the snow. The ideal place to grow it is in a pocket of rather rich though well-drained soil amongst stones; a private place which it can have all to itself for the short but grateful days of its consummation.

‘Reticulata – the netted iris. Not the flower is netted, but the bulb. The bulb wears a little fibrous coat, like a miniature fishing-net. It is a native of the Caucasus, and there is a curious fact about it: the Caucasian native is reddish, whereas our European garden form is a true Imperial purple …

‘I do suggest that every flower-lover should grow a patch of the little reticulata somewhere in his garden. The variety Cantab, a pale turquoise blue, flowers about a fortnight earlier as a rule; Hercules, a subfusc ruby-red, comes at the same time as the species.’

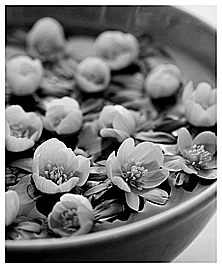

Aconites would add to this delicate mix, putting in an appearance at a bleak and freezing moment early in the year. The great thing about aconites, as Vita says, is that without any pampering they will gradually spread all through any shady spot in the garden. Dig up a clump just after flowering – ‘in the green’ – and scatter it to several other places that would be cheered by a January–February carpet of gold. You’ll forget about it for a couple of years, but then, settled in, it will start to put on a show and will do so for decades. Pick a few to arrange in a tiny vase or float some in a shallow bowl supported on crisp beech leaves.

A bowl of winter aconites – Eranthis hyemalis.

‘The courage of some small and apparently fragile flowers never ceases to amaze me,’ Vita says. ‘Here are we humans, red-nosed and blue-cheeked in the frost and the snow, looking dreadfully plain; but there are the little flowers coming up, as brave and gay as can be, unaffected by snow or frost. The winter aconite is a cheerful resister, coming through the white ground with puffs of snow all over his bright burnished face, none the worse in his January–February beauty, and increasing from self-sown seedlings year after year.

‘We cannot be reminded too often of so dear and early a thing. It started flowering here, in Kent, on January 20th; I made a note in my diary. Then frost came, turning it into tiny crystallized apricots, like the preserved fruits one used once to get given for Christmas. They shone; they sparkled in the frost. Then the frost went, and with the thaw, they emerged from their rimy sugar coating into their full, smooth, buttercup yellow on a February day with its suggestion of spring, when the first faint warmth of the sun falls as a surprise upon our naked hands.

‘I am being strictly correct in comparing the varnished yellow of the Winter Aconite to our common buttercup, for they both belong to the same botanical order of the Ranunculaceae.

‘The proper name of the Winter Aconite is Eranthis. Eranthis hyemalis is the one usually grown, and should be good enough for anybody. These are cheap, but if you want a superior variety you can order E. Tubergenii. I daresay this would be worth trying. Personally I am very well satisfied with the smudge of gold given me by hyemalis (meaning, of winter). It has the great advantage of flourishing almost anywhere, in shade or sun, under trees or in the open, and also of producing a generous mustard-and-cress-like crop of self-sown seedlings which you can lift and transplant. It is better to do this than to lift the older plants, for it is one of those home-lovers that likes to stay put, and, indeed, will give of its best only when it has had a couple of years to become established. So do not get impatient with it at first. Give it time.

‘There are many small early things one could happily associate with it; in fact, I can imagine, and intend to plant, a winter corner, stuffed with little companions all giving their nursery party at the same time: Narcissus minimus [now known as Narcissus asturiensis] and Narcissus nanus; the bright blue thimbles of the earliest grape hyacinth, Muscari azureus; the delicate spring crocus Tomasinianus, who sows himself everywhere, scores of little Thomases all over the place … but I must desist.’

Cyclamen give a similar delicacy and scale at almost any time of year, their leaves often as appealing as the flowers themselves. For January and February, you want Cyclamen coum, one of the first to appear in any garden. These come in a range of colours, but none better than that deep saturated pink. You can plant this right in amongst the roots of deciduous trees such as beech and oak, and they will poke their heads up through the coppery carpet of fallen leaves. They cope perfectly happily in the desert of dry shade, and Vita’s selection (below) will give you a succession of flowers to cover most of the year. Like the species crocuses and aconites, these will gradually self-sow and naturalise.

One of the most beautiful winter containers I’ve ever seen was planted with Cyclamen coum as a carpet below the magnificent snowdrop, ‘Samuel Arnott’. This was created by Julian and Isabel Bannerman at Hanham Court, outside Bristol, and is just the sort of thing Vita might have done in one of her stone troughs, a simple sweep of something small-scale, jewelled and glorious.

Cyclamen coum and Galanthalus ‘Samuel Arnott’.

Vita goes into detail: ‘There are two kinds of cyclamen: the Persian, which is the one your friends give you, and which is not hardy [see more on this in the greenhouse section here], and the small, out-door one, a tiny edition of the big Persian, as hardy as a snowdrop. These little cyclamen are among the longest-lived of garden plants. A cyclamen corm will keep itself going for more years than its owner is likely to live. They have other advantages: (1) they will grow under trees, for they tolerate, and indeed enjoy, shade; (2) they do not object to a limy soil; (3) they will seed themselves and (4) they will take you round the calendar by a judicious planting of different sorts. C. neapolitanum, for instance, will precede its ivy-like leaves by its little pink flower in late autumn, white flowers if you get the variety album; C. coum, pink, white, or lilac, will flower from December to March; C. ibericum from February to the end of March; C. balearicum will then carry on, followed by C. repandum, which takes you into the summer; and, finally, C. europaeum for the late summer and early autumn …

‘Anyone who grows the little cyclamen will have observed that they employ an unusual method of twiddling a kind of corkscrew, or coil, to project the seeds from the capsule when ready. One would imagine that the coil would go off with a ping, rather like the mainspring of a clock when one overwinds it, thus flinging the seeds far and wide, and this indeed was the theory put forward by many botanists.

‘It would appear, however, that nothing of the kind happens, and that the seeds are gently deposited on the parent corm. Why, then, this elaborate apparatus of the coil, if it serves only to drop the seed on to a hard corm and not on to the soft receptive soil? It has been suggested … that this concentration of the seeds may be Nature’s idea of providing a convenient little heap for some distributing agent to carry away, and [a correspondent] points out that ants may be seen, in later summer, hurrying off with the seeds until not one is left. I confess that I have never sat up with a cyclamen long enough to watch this curious phenomenon of the exploding capsule; and I still wonder how and why seedlings so obligingly appear in odd corners of the garden – never, I must add, very far away from the parent patch.

‘So accommodating are they that you can plant them at almost any time, though ideally they should be planted when dormant, i.e. in June or July.’

Winter has always been an important season in Vita’s garden, and she came up with the idea of a special corner, jam-packed with all the plants just described: ‘January to the end of March. I wish we had a name for that intermediate season which includes St. Valentine’s Day, February 14th, and All Fools’ Day, April 1st. It is neither one thing nor the other, neither winter nor spring. Could we call it wint-pring, which has a good Anglo-Saxon sound about it, and accept it, like marriage, for better or worse?

‘My wint-pring corner shall be stuffed with every sort of bulb or corm that will flower during those few scanty weeks. The main point is that it shall be really stuffed; crammed full; packed tight…’

In addition, ‘there will be some early tulips, such as Tulipa biflora and turkestanica and Kaufmaniana, the water-lily tulip, flowering in March. There will be Scilla biflora and Scilla Tubergeniana, both flowering in February; and as a ground work, to follow after the winter aconites, I shall cram the ground with the Greek Anemone blanda, opening her starry blue flower in the rare sun of February, and with the Italian Anemone Apennina, who comes a fortnight later and carries on into March and is at her best in April. Terrible spreaders, these anemones; but so blue a carpet may gladly be allowed to spread.

‘… The winter corner should be cheap to plant; and needs, humbly, only a little patch of ground where you can find one. Let it be in a place which you pass frequently, and can observe from day to day.’

SPRING

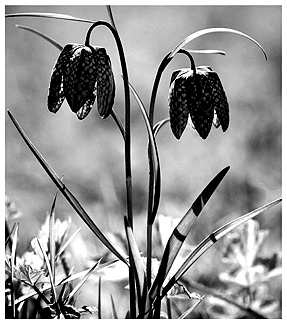

Vita loved the meadow fritillary perhaps more than any spring bulb, partly for its subtlety, for, ‘less showy than the buttercup, less spectacular than the foxglove in the wood, it seems to put a damask shadow over the grass, as though dusk were falling under a thunder-cloud that veiled the setting sun…’ She also loved it for its hidden drama. It is, as she says in Some Flowers, ‘a flower to put in a glass on your table. It is a flower to peer into. In order to appreciate its true beauty, you will have to learn to know it intimately. You must look closely at all its little squares, and also turn its bell up towards you so that you can look right down into its depths, and see the queer semi-transparency of the strangely foreign, wine-coloured chalice. It is a sinister little flower, sinister in its mournful colours of decay.’

Meadow fritillary – Fritillaria meleagris.

Vita planted lots of snakeshead fritillaries in the Orchard underneath the fruit trees: ‘In its native state the bulb grows very deep down,’ she explains, ‘so taking a hint from Nature we ought to plant it in our own gardens at a depth of at least six to eight inches. There is another good reason for doing this: pheasants are fond of it, and are liable to scratch it up if planted too shallow. Apart from its troubles with pheasants, it is an extremely obliging bulb and will flourish almost anywhere in good ordinary soil, either in grass or in beds. It looks best in grass, of course, where it is naturally meant to be, but I do not think it much matters where you put it, since you are unlikely to plant the million bulbs which would be necessary in order to reproduce anything like the natural effect, and are much more likely to plant just the few dozen which will give you enough flowers for picking.’

The heavy soil and poor drainage of the Sissinghurst Orchard make this ideal fritillary ground. They have been successful, and have self-sown for decades into robust patches flowering in April and May. That’s where you see them in the wild – in damp, low-lying meadows, particularly in the Thames Valley, where they have self-sown now for millennia. As we’ve seen with other plants, that’s just the look Vita wanted in her garden – damask shadows across her Orchard grass and enough for her to pick whenever she wanted. They only last three or four days in water, but there’s nothing better.

Show auriculas might be extraordinary, but it is also worth growing the garden forms (see the section on her cold greenhouse for the show varieties, here). As she said, ‘we may have modestly to content ourselves with the outdoor or Alpine Auricula, but we have nothing to complain of, for it is not only the painter’s but also the cottager’s flower. It is indeed one of those flowers which look more like the invention of a miniaturist or of a designer of embroidery, than like a thing which will grow easily and contentedly in one’s own garden. In practical truth it will flourish gratefully given the few conditions it requires: a deep, cool root-run, a light soil with plenty of leaf-mould … a certain amount of shade during the hotter hours of the day, and enough moisture to keep it going. In other words, a west or even a north aspect will suit it well, so long as you do not forget the deep root-run, which has the particular reason that the auricular roots itself deeper and deeper into the earth as it grows older. If you plant it in shallow soil, you will find that the plant hoists itself upwards, away from the ground, eventually raising itself on to a bare, unhappy-looking stem, whereas it really ought to be flattening its leaves against the brown earth, and making rosette after rosette of healthy green. If your auriculas are doing this, you may be sure they are doing well, and you may without hesitation dig them up and divide them as soon as they have ceased flowering, that is to say in May or June, and re-plant the bits you have broken off, to increase your group next year.

‘It is well worth trying to raise seedlings from your own seed, for you never know what variation you may get. The seed germinates easily in about ten days or a fortnight; sow it in a sandy compost, barely covering the seed; keep the seedlings in a shady place, in pots if you like, or pricked out on a suitable border till they are big enough to move to their permanent home.’

Vita was a great one for tulips, the showy ‘parrots’ for picking and the early-flowering, persistent and easy species for the Spring Garden (the Lime Walk) and Cottage Garden, and to include in her wint-pring corner – but it was Tulipa clusiana, the ‘Lady Tulip’, with its painterly quality, that stood out. Look for the white and red ‘Peppermint Stick’ cultivar that Vita writes about, as well as the creamy yellow and red hybrid, T. clusiana ‘Cynthia’. They’re both beautiful.

‘[Tulipa clusiana] is familiarly called the Lady Tulip, but always reminds me more of a regiment of little red and white soldiers. Seen growing wild on Mediterranean or Italian slopes, you can imagine a Lilliputian army deployed at its spring manoeuvres. I suppose her alleged femineity is due to her elegance and neatness, with her little white shirt so simply tucked inside her striped jacket, but she is really more like a slender boy, a slim little officer, dressed in a parti-coloured uniform of the Renaissance.

The Lady tulip – Tulipa clusiana.

‘Clusiana is said to have travelled from the Mediterranean to England in 1656 … Her native home will suggest the conditions under which she likes to be grown: a sunny exposure and a light rich soil. If it is a bit gritty, so much the better.’

On a different scale, but still a plant which rewards close examination, Vita loved the imperial fritillary (Fritillaria imperialis) and grew it in the Cottage Garden, as well as encouraging Harold to have good clumps of it to provide a rhythm down the borders of the Lime Walk. It’s an unusual bulb and, like its relation the lily, is happy with some shade, plus a rich soil with lots of humus and leaf mould. In the right place this fritillary is exceptionally long-lived, its bulbs surviving in the same place for decades. My mother has now had it in the same shady corner of their garden for over fifty years. Recently it has suffered the scourge of the lily beetle, which feeds and breeds on this too.

Crown Imperial – Fritillaria imperialis.

‘It was once my good fortune to come unexpectedly across the Crown Imperial in its native home,’ Vita notes. ‘In a dark, damp ravine in one of the wildest parts of Persia, a river rushed among boulders at the bottom, the overhanging trees turned the greenery almost black, ferns sprouted from every crevice of the mossy rocks, water dripped everywhere, and in the midst of this moist luxuriance I suddenly discerned a group of the noble flower. Its coronet of orange bells glowed like lanterns in the shadows in the mysterious place. The track led me downwards towards the river, so that presently the banks were towering above me, and now the Crown Imperials stood up like torches between the wet rocks, as they had stood April after April in wasteful solitude beside that unfrequented path. The merest chance that I had lost my way had brought me into their retreat; otherwise I should never have surprised them thus. How noble they looked! How well-deserving of their name! Crown Imperial – they did indeed suggest an orange diadem fit to set on the brows of the ruler of an empire. That was a strange experience … Since then, I have grown Crown Imperials at home. They are very handsome, very sturdy, very Gothic …

‘Like the other members of its family, the stateliest of them all has the habit of hanging its head, so that you have to turn it up towards you before you can see into it at all. Then and then only will you be able to observe the delicate veining on the pointed petals. It is worth looking into these yellow depths for the sake of the veining alone, especially if you hold it up against the light, when it is revealed in a complete system of veins and capillaries. You will, however, have to pull the petals right back, turning the secretive bell into something like a starry dahlia, before you can see the six little cups, so neatly filled to the brim, not overflowing, with rather watery honey at the base of each petal, against their background of dull purple and bright green. Luckily it does not seem to resent this treatment at all and allows itself to be closed up again into the bell-like shape which is natural to it, with the creamy pollened clapper of its stamens hanging down the middle.

‘It always reminds me of the stiff, Gothic-looking flowers one sometimes sees growing along the bottom of a mediaeval tapestry, together with irises and lilies in a fine disregard for season. Grown in a long narrow border, especially at the foot of an old wall of brick or stone, they curiously reproduce this effect. It is worth noting also how well the orange of the flower marries with rosy brick, far better than any of the pink shades which one might more naturally incline to put against it. It is worth noting also that you had better handle the bulbs in gloves for they smell stronger than garlic.

‘Note: The disadvantage of this fritillary is that it is apt to come up “blind”, i.e. with leaves and no flower. I noted with interest that this occurred also in its native habitat.’

SUMMER

At the end of spring and through the summer, painterly plants tend to get lost in the abundance and colour of the garden in general, but there are still a few that Vita wrote about as cosier garden, desk and greenhouse companions.

It was the intricate markings of the bearded iris – landing lights for pollinators – as well as their unusual flower shape, petal texture and their intense, spicy exotic scents which for Vita put these in an early-summer class of their own. They are definitely flowers best peered into, nose and all. As she writes, ‘No adjective, however lyrical, can exaggerate the soft magnificence of the moderns [the bearded irises], rivalled only by the texture of Genoese velvet. We have to go back to the Italian Renaissance to produce a flower as soft, as rich, as some of those velvets one used to buy for next to nothing in Venice and Rome, years ago, when one was young and scraps of velvet went cheap. Only the pansy, amongst other flowers, shares this particular quality.

‘Stately in their bearing, the irises look their best on either side of a flagged path. The grey of the flat stone sets off both their colour and their contrasting height … A straight path gives an effect of regimental parade, which suits the irises, whose leaves suggest uplifted swords.’ (see photograph here.)

There were lots planted in the Cottage Garden in red, gold and bronze, as well as drifts encouraged to establish themselves in the Rose Garden. Here Vita grew the highly scented mauve ‘Jane Phillips’ as well as some dark velvet purples. The Purple Border and White Garden accommodated them too, with their huge ghostly flowers, pulsing out their scent most strongly at night, when this garden comes into its own.

The varieties available now are almost all different from the ones Vita could choose from when she was ordering in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, but the colour range available is much the same. The petals were less ruffled then, with a straighter edge, more elegant, more refined. Look out for these if you can find them, less fussy than our modern forms. ‘[Irises] are the easiest plants to grow,’ she says. ‘All they ask is a well-drained, sunny place so that their rhizomes may get the best possible baking; a scatter of lime in autumn or in spring; and division every third year.

‘It may sound tiresome and laborious to divide plants every third year, but in the case of the iris it is a positive pleasure. It means that they increase so rapidly. Relatively expensive to buy in the first instance, by the end of the second or third year you have so large a clump from a single rhizome that you can break them up, spread them out, and even give them away.

‘Dig up the clump, which looks like a cluster of fat brown crayfish, and you will find a number of white roots just beginning to grow. Cut out the centre of the clump, which is the part that has flowered, and retain only the younger side-bits. Replant these, singly, one by one, without burying them under the soil. This sounds easier than it is in practice, for you have to set them firmly in order to prevent them from getting loosened and wobbling about. It is one of those things that expert gardeners cheerfully advise one to do, and then go off leaving one wondering how to do it.

‘An old argument concerns the shortening of the leaves. Some people say you shouldn’t; other people say you should. The people who say you should, contend that the newly-planted rhizome runs less risk of being loosened by wind when it has not got a tall fan of leaves to be blown over. I am on the side of the shorteners. I would not cut the leaf down to the base, of course I would not, but I cannot see that it does any harm to cut the leaves half way down, because the top-tips will die off anyhow and turn brown, so there can be no loss of green vegetable nutriment to the root at the bottom, that secret store whence astonishing flowers astonishingly arise.

‘The best time to do this is immediately after they have finished flowering – in other words, at the end of June or beginning of July.’

An abundance of bearded irises as a theme remains at Sissinghurst seventy years on: the May and June Rose Garden in particular is packed with many different varieties, both tall and dwarf. They thrive in its greensand, freely drained soil, of which most of the garden is made. As Vita said herself about the soils in this former vegetable plot, ‘The soil had been cultivated for at least four hundred years and it was not bad soil to start with, being in the main what is geologically called Tunbridge Wells sand: a somewhat misleading name, since it is not sandy, but consisted of a top spit of decently friable loam with a clay bottom, if you were so unwise as to turn up the sub-soil two spits deep.’ The bearded irises plug a gap, filling the garden with lushness after the spring abundance of bulbs, but before the roses have really got going.

On a different scale, but with their own particular delicacy, you can’t fail to fall for the alliums and eremurus, or foxtail lily. Alliums are much more widely grown now than they were when Vita was gardening; there are so many excellent and non-invasive forms such as ‘Purple Sensation’, christophii and hollandicum now available.

Allium christophii and Rosa ‘Mayflower’ in the Rose Garden at Sissinghurst.

Vita writes: ‘Mr. William Robinson, in his classic work The English Flower Garden, was very scornful of the Alliums or ornamental garlics. He said that they were “not of much value in the garden”; that they produced so many little bulblets as to make themselves too numerous; and that they smelt when crushed.

‘For once, I must disagree with that eminent authority. I think, on the contrary, that some of the Alliums have a high value in the June garden; far from objecting to a desirable plant making a spreading nuisance of itself, I am only too thankful that it should do so; and as for smelling nasty when crushed – well, who in his senses would wish wantonly to crush his own flowers?

‘Allium Rosenbachianum is extremely handsome, four feet tall, with big, rounded lilac heads delicately touched with green. Its leaves, however, are far from handsome, so it should be planted behind something which will conceal them. If you are by nature a hoarder, you can cut down the long stems after the flowers have faded and keep them with their seed-pods for what is known to florists as “interior decoration” throughout the winter [see ideas for Christmas decorations, here].

‘Like most of the garlics, they demand a sunny, well-drained situation. Not expensive … for the effect they produce, they get better and better after the first year of planting.

‘Allium albo-pilosum, a Persian, my favourite, is lilac in colour, two feet high or so. It’s June-flowering, a native of Turkestan, it comes up in a large mop-sized head of numerous perfectly star-shaped flowers of sheeny lilac, each with a little green button at the centre, on long thin stalks, so that the general effect is of a vast mauve-and-green cobweb, quivering with its own lightness and buoyancy. [They are quite expensive,] … but even a group of six makes a fine show. Quite easy to grow, they prefer a light soil and a sunny place, and may be increased to any extent by the little bulbils which form round the parent bulb, a most economical way of multiplying your stock. They would mix very happily with the blue Allium azureum, sometimes called A. caeruleum, in front of them. These [are cheap] … not quite so tall, and overlap in their flowering season, thus prolonging the display.’

Eremuri give you a vertical firework display par excellence, and although they’re expensive, they’re worth every penny. On a heavy soil they’re safest lifted after the leaves have begun to die back, but if your soil is freely drained leave them, as Vita says, just where they are. She was fond of them, and had groups planted in the Rose and Cottage Gardens. They have gone from here now as they don’t seem to do well.

‘Visitors to June and July flower-shows,’ she notes, ‘may have been surprised, pleased, and puzzled by enormous spikes, six to eight feet in height, which looked something like a giant lupin, but which, on closer inspection, proved to be very different. They were to be seen in various colours: pale yellow, buttercup-yellow, greenish-yellow, white and greenish-white, pink, and a curious fawn-pink which is as hard to describe, because as subtle, as the colour of a chaffinch’s breast.

Foxtail lilies – Eremurus.

‘These were Eremuri, sometimes called the fox-tail lily and sometimes the giant asphodel. They belong, in fact, to the botanical family of the lilies, but, unlike most lilies, they do not grow from a bulb. They grow from a starfish-like root, which is brittle and needs very careful handling when you transplant it. I think this is probably the reason why some people fail to establish the eremurus satisfactorily. It should be moved in the last weeks of September or the first weeks of October, and it should be moved with the least possible delay. The roots should never be allowed to wait, shrivelling, out of the ground. Plant them instantly, as soon as they arrive from the nursery. Spread out the roots, flat, in a rather rich loamy soil, and cover them over with some bracken to protect them from frost during their first winter. Plant them under the shelter of a hedge, if you can; they dislike a strong wind, and the magnificence of their spires will show up better for the backing of a dark hedge. They like lime and sunshine.

‘Thus established, the fox-tail lily should give increasing delight as the years go by. They get better and better as they grow older and older, throwing up more and more spires of flower from each crown of their star-fish root. I must admit that [they are expensive], but it is a good investment. There are several sorts obtainable: the giant Eremurus robustus, which flowers in June, and then the smaller ones, the Shelford hybrids and the Warei hybrids in their strange colours. Splendid things; torches of pale colour, towering, dwarfing the ordinary little annuals. Aristocrats of the garden, they are well worth [their price].’

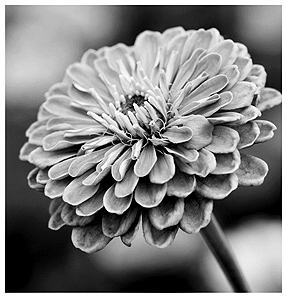

For later in the summer, zinnias have the same sort of quality, with intricate flowers, which one wants to look at close to. Vita adored them, encouraging us to grow a good range of colours, in bold splashes rather than anything too discreet; but interestingly, she always recommended rogueing out the magentas. This was a coarse colour, she felt, which lowered the high zinnia tone.

Zinnias thrive in hot climates – the best ones I’ve ever seen were sown as a hedge in Sri Lanka – but they do fine here, particularly if sown direct (as she says), so they suffer no root disturbance. Don’t sow too early. Wait even in the south of England until late May, early June.

Zinnias are no longer to be seen at Sissinghurst, apart from perhaps as a line left in a patch reserved for flowers for cutting, hidden away in the nursery. They may be planted in drifts, the colours mixed together ‘higgledy-piggledy, when they look like those pats of paints squeezed out upon the palette’. This is how they are grown so spectacularly at Great Dixter – and at Sissinghurst they could help with Vita’s overbrimming theme.

Zinnia ‘Giant Dahlia’.

‘The original zinnia, or Zinnia elegans, was introduced into European countries in 1796, and since then has been “improved” into the garden varieties we now know and grow. Many flowers lose by this so-called improvement; the zinnia has gained. Some people call it artificial-looking, and so in a way it is. It looks as though it had been cut out of bits of cardboard ingeniously glued together into the semblance of a flower. It is prim and stiff and arranged and precise, almost geometrically precise, so that many people who prefer the more romantically disorderly flowers reject it just on account of its stiffness and regularity.

‘“Besides,” they say, “it gives us a lot of trouble to grow.” It is only half-hardy in this country, and thus has to be sown in a seed box under glass in February or March; pricked out; and then planted out in May where we want it to flower. We have to be very careful not to water the seedlings too much, or they will damp off and die. On the other hand, we must never let the grown plant suffer from drought. Then, when we have planted it out, we have to be on the look-out for slugs, which have for zinnias an affection greatly exceeding our own. Why should we take all this trouble about growing a flower which we know is going to be cut down by the first autumn frost?

‘Such arguments crash like truncheons, and it takes an effort to renew our determination by recalling the vivid bed which gave us weeks of pleasure last year. For there are few flowers more brilliant without being crude, and since they are sun-lovers the maximum of light will pour on the formal heads and array of colours. The disadvantage of growing them in seed boxes as a half-hardy annual may be overcome by sowing them where they are to remain, towards the end of May. I do believe that you get sturdier plants in the long run, when the seedlings have suffered no disturbance. Sow the seeds in little parties of three or four, and thin them remorselessly out when they are about two inches high, till only one lonely seedling remains. It will do all the better for being lonely, twelve inches away from its nearest neighbour. It will branch and bulge sideways if you give it plenty of room to develop, and by August or September will have developed a spread more desirable in plants than in human beings.

‘In zinnias, you get a mixture of colours seldom seen in any other flower: straw-colour, greenish-white, a particular saffron-yellow, a dusky rose-pink, a coral-pink. The only nasty colour produced by the zinnia is a magenta, and this, alas, is produced only too often. When magenta threatens, I pull it up and throw it on the compost heap, and allow the better colours to have their way.

‘Whether we grow them in a mixture or separate the pink from the orange, the red from the magenta, is a matter of taste. [And] personally I like them … all by themselves, not associated with anything else.

‘As cut flowers they are invaluable: they never flop, and they last I was going to say for weeks.’

AUTUMN

With abundance and growth curves tailing off by the autumn, the more delicate plants again come into their own. Vita was interested in having some special intimate things for admiring specifically at this time.

She so loved the colour of the gentian that she created a miniature garden, or ‘lawn’, devoted solely to it. She cleared the grass from a small square as you enter the Orchard from the White Garden, and in a similar style to her thyme lawn, made one filled only with gentians.

Gentians, like polyanthus, struggle if they’re left in the same soil for year after year. They prefer to keep on the move, needing to colonise new ground to grow well. By the late 1960s, after twenty-five years, the gentian bed at Sissinghurst was no longer looking good, so Pam and Sybille took it out. It would be a spectacular thing to restore, moving it every few years to keep the colony growing well.

‘The blue trumpets of Gentiana sino-ornata have given great pleasure during September,’ Vita remarked in October 1949. ‘Some people seem to think they are difficult to grow, but, given the proper treatment, this is not true. They like semi-shade (I grow mine round the foot of an apple tree, which apparently suffices them in this respect); they like plenty of moisture, which does mean that you have to water them every other evening in an exceptionally dry summer; and they utterly abhor lime. This means that if you have a chalky soil you had better give up the idea of growing these gentians unless you are prepared to dig out a large, deep hole and fill it entirely with peat and leaf-mould.

‘It is a safe rule that those plants which flourish in a spongy mixture of peat and leaf-mould will not tolerate lime; and the gentians certainly revel in that sort of mixture. As a matter of fact, I planted mine in pure leaf-mould and sand without any peat, and they seem very happy … The boxful of plants I set out last autumn, the gift of a kind friend in Scotland who says she has to pull them up like weeds in her garden (lucky woman), have now grown into so dense a patch that I shall be able to treble it next year [which she did]. For the gentian has the obliging habit of layering itself without any assistance from its owner, and I have now discovered that every strand a couple of inches long has developed a system of sturdy white roots, so that I can detach dozens of little new plants in March without disturbing the parent crown, and, in course of time, can carpet yards of ground with gentian if I wish, and if my supply of leisure, energy, and leaf-mould will run to it.

‘Gentiana sino-ornata is very low-growing, four inches high at most, but although humble in stature it makes up for its dwarfishness by its brilliance of colour, like the very best bit of blue sky landing by parachute on earth. By one of those happy accidents which sometimes occur in gardening, I planted my gentians near a group of the tiny pink autumn cyclamen, Cyclamen europaeum, which flowers at exactly the same time. They look so pretty together, the blue trumpets of the gentian and the frail, frightened, rosy, ears-laid-back petals of the cyclamen: they share something of the same small, delicate quality. It is one of the happiest associations of flowers.

‘So please plant Gentiana sino-ornata in a leaf-mould shady bed in your garden, with an inter-planting of Cyclamen europaeum. The same conditions will suit them both.’

She added a postscript a few weeks later:

‘Some weeks ago I wrote that the blue trumpets of Gentiana sino-ornata had given great pleasure during September. I little knew, then, how I was underestimating their value; so, in fairness to this lovely thing, I would like to state here and now, on this eighteenth day of November when I write this article, that I have to-day picked at least two dozen blooms from my small patch. They had avoided the gales by cowering close to the ground, but they had suffered some degrees of frost; they looked miserable and shut up; I hesitated to pick them, thinking that they were finished for the year; but now that I have brought them into a warm room and put them into a bowl under a lamp they have opened into the sapphire-blue one expects of the Mediterranean.

‘This mid-November bowl has so astonished me, and made me so happy, gazing at it, that I felt I must impart my delight to other people in the hope that they would begin to plant this gentian.’

It’s sad the gentian patch is no longer at Sissinghurst.

I remember coming across Ampelopsis heterophylla (which was called Vitis in Vita’s day) fifteen years ago against a house in Hastings and being stopped in my tracks by the beauty of its blue berries, stippled in navy, reminiscent of a shiny thrush’s egg. Its common name is porcelain berry vine, and you can see why. It fruits best in full sun with its roots restricted, so cram it in somewhere in a narrow bed below a wall or frame – it’s a good idea to keep it away from the guttering of the house. More of us should find a site for this extraordinary fruiting climber. It can become invasive in hot, humid climates, but it won’t get rampant here. Vita writes in 1947:

‘A vine which is giving me great pleasure at the moment is Vitis heterophylla, an East Asian. You can’t eat it, but you can pick it and put it in a little glass on your table, where its curiously coloured berries and deeply cut leaves look oddly artificial, more like a spray designed by a jeweller out of dying turquoises than like a living thing. Yet it will grow as a living thing, very rapidly, on the walls of your house, or over a porch, hanging in lovely swags of its little blue berries, rather subtle, and probably not the thing that your next-door neighbour will bother to grow or perhaps doesn’t know about. There are some obvious plants which we all grow: useful things, and crude. We all know about them. But the real gardener arrives at the point when he wants something rather out of the common run, and that is why I make these suggestions which might turn your garden into something a little different and a little more interesting than the garden of the man next door.’

The berries of ampelopsis will keep us all going with delicate things to bring inside until the blossom of Prunus subhirtella ‘Autumnalis’ begins to appear in November. This is a little tree which, as its name suggests, ought to flower in autumn, and it ranks amongst Vita’s favourite plants. She loved many flowering shrubs but particularly this one, blooming at such a grey and gloomy part of the year, a small bough of it an exquisite and delicate thing:

Autumn-flowering cherry Prunus subhirtella ‘Autumnalis’.

‘In England Prunus subhirtella autumnalis might more properly be called winter-flowering, for it does not open until November, but in its native Japan it begins a month earlier; hence its autumnal name. Here, if you pick it in the bud and put it in a warm room or a greenhouse, you can have the white sprays in flower six weeks before Christmas, and it will go on intermittently, provided you do not allow the buds to be caught by too severe a frost, until March … It was in full flower here in the open during the first fortnight of November; I picked bucketfuls of the long, white sprays; then came two nights of frost on November 15th and 16th; the remaining blossom was very literally browned-off; I despaired of getting any more for weeks to come. But ten days later, when the weather had more or less recovered itself, a whole new batch of buds was ready to come out, and I got another bucketful as fresh and white and virgin as anything in May.

‘There is a variety of this cherry called rosea, slightly tinged with pink; I prefer the pure white myself, but that is a matter of taste … It is perhaps too ordinary to appeal to the real connoisseur – a form of snobbishness I always find hard to understand in gardeners – but its wands of white are of so delicate and graceful a growth, whether on the tree or in a vase, that it surely should not be condemned on that account. It is of the easiest cultivation, content with any reasonable soil, and it may be grown either as a standard or a bush; I think the bush is preferable, because then you get the flowers at eye-level instead of several feet above your head – though it can also look very frail and youthful, high up against the pale blue of a winter sky.

‘There is also another winter-flowering cherry, Prunus serrulata Fudanzakura, which I confess I neither grow nor know, and I don’t like recommending plants of which I have no personal experience, but the advice of Captain Collingwood Ingram, the “Cherry” Ingram of Japanese cherry fame, is good enough for me and should be good enough for anybody. This, again, is a white single-flowered blossom with a pink bud, and may be admired out of doors or picked for indoors any time between November and April. So obliging a visitor from the Far East is surely to be welcomed to our gardens.

‘By the way, I suppose all those who like to have some flowers in their rooms even during the bleakest months are familiar with the hint of putting the cut branches, such as the winter-flowering cherry, into almost boiling hot water? It makes them, in the common phrase, “jump to it” [see here for more flower-conditioning advice].’