9 Polypores

These tough, shelflike or bracketlike fungi are major decayers of wood. There is a sponge layer underneath the cap as in the boletes, but in some cases the individual pores that compose it are so tiny that the surface looks smooth. Polypores can be distinguished from boletes by their shape; those that grow on the ground are tougher than boletes and usually have an off-center stalk. There is no veil.

Few polypores are tender enough to eat, but many are used medicinally (this page). Only a few species are depicted here. For a more detailed treatment, see MD 549–611.

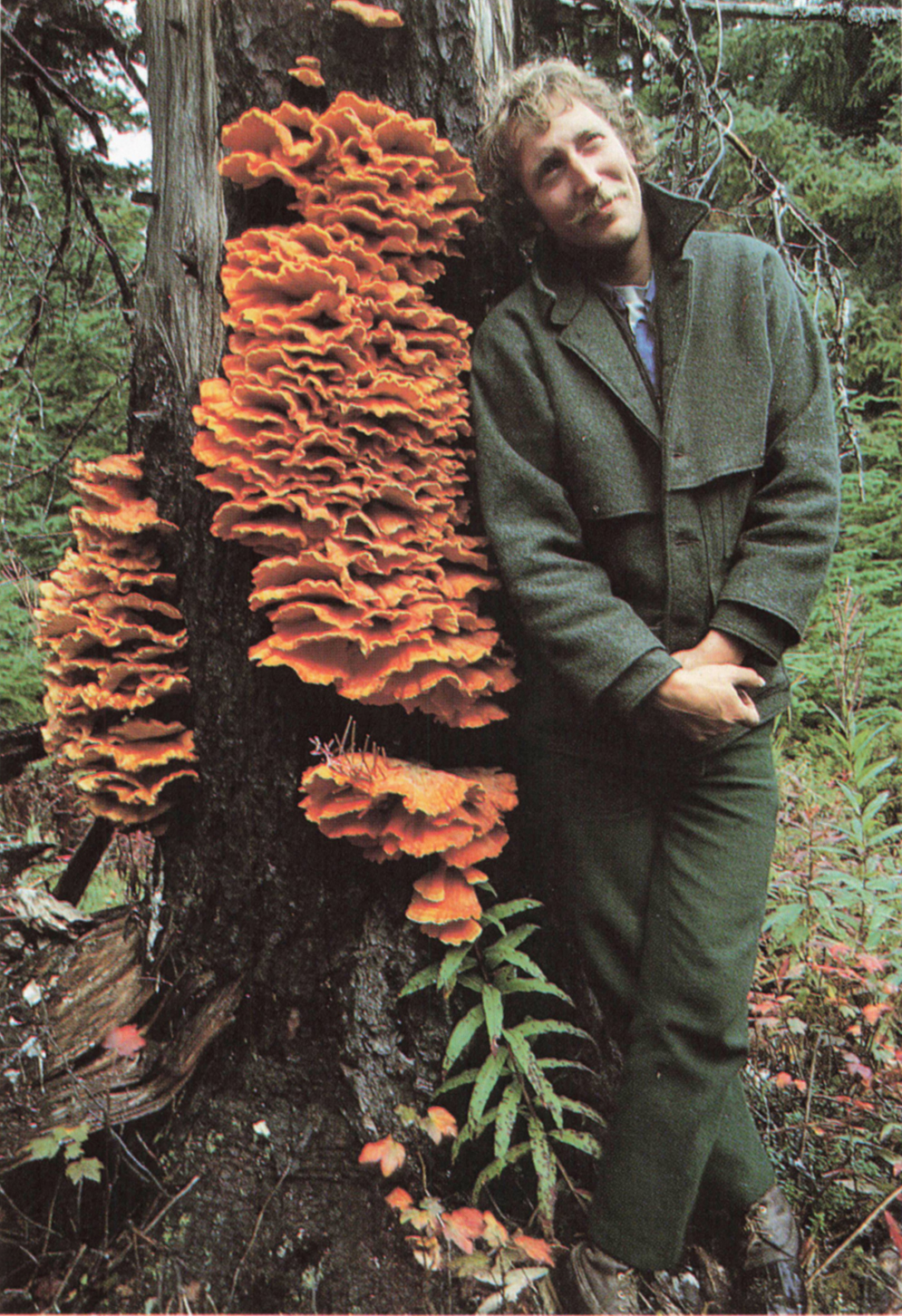

Sulfur Shelf (Laetiporus sulphureus)

Other Names: Chicken of the Woods, Polyporus sulphureus.

Key Features:

1. Mushroom shelflike, growing in overlapping masses or rosettes (or sometimes singly) on logs and stumps.

2. Cap (upper surface of shelf) bright yellow-orange to orange or salmon-colored.

3. Underside of cap bright sulfur-yellow when fresh.

4. Stalk absent or nearly absent.

Other Features: Medium-sized to very large; juicy when young but tough and fibrous at maturity and fading dramatically in old age (eventually becoming brittle and whitish); pores on underside of cap often so tiny they can hardly be seen.

Where: In shelving masses or clusters or sometimes singly on logs, trunks, and stumps of both hardwoods and conifers (eucalyptus, oak, plum, fir, hemlock, spruce, etc.); widespread and common. It requires little moisture to fruit.

Edibility: Widely regarded as edible when tender, but often causing gastrointestinal distress.

Note: Also shown on this page, this colorful mushroom has no poisonous look-alikes but is sometimes poisonous itself. Perhaps because eucalyptus is the favored host in heavily populated central and southern California, the poisonings are often blamed on the eucalyptus. However, sulfur shelves growing on other trees have also caused digestive upsets. Conclusion: if you eat and enjoy this mushroom, always cook it thoroughly and do not serve it to lawyers, landlords, employers, policemen, pit bull owners, or others whose good will you cherish! See MD 572–573 and plates 154–155.

Beefsteak Fungus (Fistulina hepatica)

Other Names: Ox Tongue, Poor Man’s Beefsteak.

Key Features:

1. Mushroom shelflike or tonguelike, exuding a dark red liquid when fresh.

2. Cap (upper surface of shelf) reddish, reddish-orange, pinkish, or liver-colored; at first velvety but becoming gelatinous in old age or wet weather.

3. Underside with a sponge layer (actually a layer of closely packed tubes or pipes).

4. Flesh streaked or marbled (best seen when sliced—see this page).

5. Stalk absent or present only as a tough, stubby base.

6. Growing on hardwoods.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; flesh juicy when young, tougher in age; pore (sponge) surface white to yellowish or pinkish when fresh, but aging or bruising reddish-brown.

Where: At bases of trees and on stumps, usually of chinquapin (a relative of chestnut); limited to the West Coast, most frequent in northern California.

Edibility: Edible. It has an unusual sour taste which rules out normal methods of mushroom preparation. However, it is good raw or marinated in salads and sushi, and also makes excellent jerky.

Note: This mushroom is a good source of vitamin C. When it oozes dark red juice it looks like a slab of raw meat, and when cooked it resembles liver. See MD 553-554 for more information.

Beefsteak fungus sliced to show the distinctively marbled flesh.

Beefsteak Fungus Jerky

I slice them into about ⅜″ strips and put them in salt water and pepper and marinate them overnight, or for 24 hours. Then I just leave them in an electric dehydrator or one of those heat things until they’re real dry, like beef jerky. They taste great!

—Chris Sterling

Sheriff’s Log

2/7 9:30 a.m. — Dorothy Willhite said one of her sons took $3,500 from her purse. The son returned the money to his mother without prompting by deputies.

2/8 11:25 a.m. — Martha Soto complained to Deputy Ingram that someone had maliciously scratched her car, causing $1,059.00 in damages.

2/8 3:35 p.m. — Bill Sanders reported a neighbor’s pigs loose on his property.

2/9 8:48 p.m. — An unwanted drunk left the Boonville Lodge before a deputy could arrive to eject him.

2/12 2:17 p.m. — Bob Sanders complained to Deputy Pendergraft that a neighbor’s pigs were loose on his property. 2/13 9:10 p.m. — Deputy Casella looked in vain for a domestic dispute reported to be raging on Haehl Street, Boonville.

Crime of the Week

Deputy Mason responded to reports of a woman screaming near the Branscomb Road turnoff, six miles north of Westport. The distressed woman turned out to be an exuberant mushroom hunter, screaming with delight at each new find.

—from The Boonville Times

Marinated raw beefsteak fungus makes a tart addition to salads.

Dyer’s Polypore (Phaeolus schweinitzii)

Left: A mature specimen with brown cap, and a view of the small yellowish to greenish-yellow pores. Right: Young specimens like these are juicier and more colorful (at least at the edge) than old ones.

Other Names: Red-brown Butt Rot, Schweinitz’s Polypore, Polyporus schweinitzii.

Key Features:

1. Typically growing in rosettes with one to several caps arising from a narrowed base or short stalk.

2. Cap bright yellow-brown to rusty-brown or dark brown with an orange, yellow, or greenish-yellow edge when fresh; entirely dark brown or red-brown when old.

3. Underside of cap(s) with a shallow sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface yellow to greenish when fresh but staining brown or blackish when bruised.

4. Flesh yellowish, rusty-brown, or brown (never white).

5. Texture at first spongy, soon becoming tough.

6. Growing at or near the bases of conifers.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large, often engulfing needles, twigs, or other debris as it grows; very young cap woolly or hairy and yellowish to orangish; pore surface brown when old.

Where: On ground near or at the bases of conifers, or occasionally shelflike on stumps and exposed roots; widespread and very common.

Edibility: Not recommended.

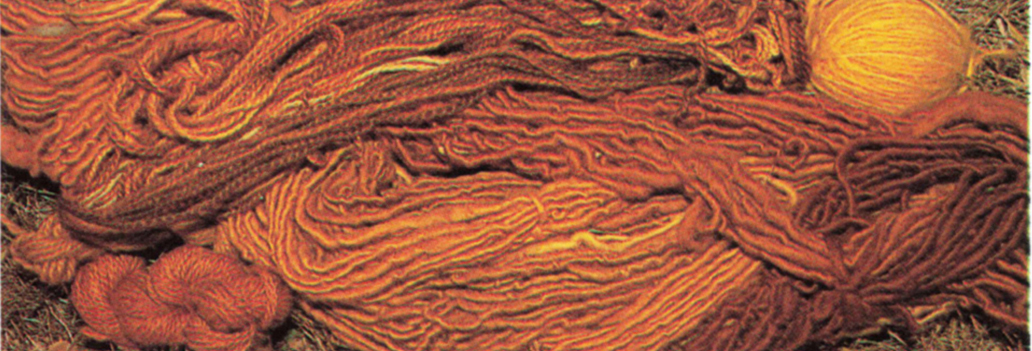

Note: This mushroom attacks the roots and butts (bases) of conifers, causing them to blow over easily. It is responsible for a large amount of timber loss, yet also contributes significantly to soil fertility by breaking down the wood into usable nutrients. It is also an excellent dye mushroom (see photos). See MD 570-571 for more information.

The dog that dyed: Poppy put up with being smeared and wrapped with shroom mush, then showed off her glorious new colors with pride.

My Most Memorable Mushroom Hunt

It was in the Olympic Mountains in late September. We walked up through the rainshadow and down into the rainforest. On the Quinault, the Steinpilz were looking exactly like stones on the hillside. Here would be a stone, and here a Steinpilz, just the cap. As for the Elwha, well, in those fabled days it was said the mushrooms there grew as big as rocking chairs or at least as big as golden footstools.

All day we rambled through the deep forest ways, placing mushrooms in one sack, berries and succulent salad herbs in another, with an occasional silver trout wrapped in moss and placed atop our packs, until at day’s end we halted, and were amazed to see the feast spread out before us, gathered by our very own hands. The fire crackled and the stars sparkled and many smiles grew deep in our bellies and then spread to our hearts.

—David Grimes

The dyer’s polypore imparts rich yellows, oranges, golds, and browns to yarn, depending on its age and the mordant used.

Blue Knight (Albatrellus flettii)

Other Names: Blue-capped Polypore, Polyporus flettii.

Key Features:

1. Cap blue, blue-green, or blue-gray when fresh.

2. Surface of cap bald, not sticky or slimy.

3. Underside of cap with a thin sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface white.

4. Sponge layer decurrent (running down the stalk), not peeling easily from the cap.

5. Stalk present, usually well developed.

6. Flesh firm and white.

7. Growing on ground.

Other Features: Medium-sized to fairly large; edge of cap often tucked under when young; cap often developing salmon or ochre stains as it ages; individual pores tiny (sometimes difficult to see); stalk central or off-center, white or tinged cap color; spores white.

Where: On ground under conifers, usually in groups or clusters; Rocky Mountains and Pacific Northwest to central California; common in some areas, otherwise infrequent.

Edibility: Edible; the firm texture requires thorough cooking.

Note: Species of Albatrellus are sometimes mistaken for boletes because they grow on the ground. However, they differ by their tough texture and thin, tough sponge layer which does not peel easily from the cap. There are several western species of Albatrellus, but only one other has a bluish cap. See MD 554-560 for more information.

Red-belted Conk (Fomitopsis pinicola)

Other Names: Red-belted Polypore, Fomes pinicola.

Key Features:

1. Mushroom shelflike or hooflike, perennial, very tough and hard.

2. Cap (upper surface of shelf) with a hard surface crust, partly or wholly reddish, cinnamon, or reddish black (usually brown or black at base and often yellow-ochre or whitish at edge).

3. Underside white or pale yellow, not staining brown when scratched.

4. Stalk absent.

5. Growing on dead wood.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; surface crust dull to slightly shiny; odor usually fragrant when fresh; pores on underside of cap often so tiny they can hardly be seen; older specimens showing stratified layers (each representing one year’s growth) when chopped open.

Where: Alone or in groups on dead conifers, less frequently on living trees and rarely on hardwoods; widespread and common. It is one of the major decayers of conifers, helping to break down the wood and return nutrients to the soil.

Edibility: Much too woody to eat, but see MD 579 for a novel recipe.

Note: This common shelf fungus is sometimes mistaken for the western varnished conk, but is harder, heavier, and perennial rather than annual. See MD 578-579 for more information.

Western Varnished Conk (Ganoderma oregonense)

Key Features:

1. Mushroom shelflike, with a shiny surface crust.

2. Cap (upper surface of shelf) wholly or partly reddish or mahogany (edge often yellow or ochre when young).

3. Flesh beneath the crust rather soft, punky, or corky when fresh.

4. Underside of cap white when fresh, staining brown when scratched.

5. Stalk absent, or if present then attached to side of cap.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large, annual; pores on underside tiny (sometimes not visible without hand lens), often brown in old age; stalk, when present, usually also with a shiny crust; spores brown.

Where: Occasionally found on dead or dying conifers from Alaska to northern coastal California, and in the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada.

Edibility: Not edible because of its texture, but can be used medicinally as a powder, extract, or tea (see note below).

Note: The shiny surface crust, which looks varnished, is the outstanding feature of this polypore and its close relatives. A similar varnished conk, G. lucidum (see below), grows on hardwoods. The Chinese call it ling chih or “mushroom of immortality,” because they believe it promotes longevity and good health and prevents cancer. G. tsugae (see photo below) is also very similar (perhaps the same) but smaller; it grows on conifers. See MD 577–578 for more information.

Varnished conks: Ganoderma tsugae (left) and ling chih (G. lucidum, right).

Mushrooms and Medicine

I’m interested in the way cultural bias engulfs science, because scientists love to think of themselves as being free from bias. They like to think they’re describing objective reality, yet they wear cultural lenses like the rest of us. In the areas of greatest emotional charge — food, sex, drugs — it’s easy to see how pervasive cultural biases affect their thinking.

I like to use the example of Chinese medicinal mushrooms. In traditional Chinese medicine, drugs that have specific effects are considered the least interesting. The most highly esteemed are those with wide-ranging effects. Many mushrooms belong to this category; the Chinese believe that they strengthen the body’s natural defenses and stimulate its healing mechanisms. Western medicine, on the other hand, is obsessed with finding “magic bullets,” specific molecules that work on specific diseases in specific ways. If someone says a drug is good for many different conditions, Western medicine loses interest. Panaceas and tonics have the sound of snake oil.

Ginseng is a good example. For years it was something that only the “crazy” Chinese (and then hippies) used. We didn’t take it seriously because its reputed wide-ranging effects didn’t fit our preconceptions of medicine. When we finally got around to looking at its chemistry, we discovered that ginseng is loaded with interesting compounds that resemble steroid hormones and can stimulate the body’s pituitary-adrenal axis (which could explain its many effects).

We know that mushrooms are full of unique, biologically active compounds like psilocybin and amanitin. Other fungi have given us some of our most powerful drugs [antibiotics], and we have one half of the world saying that mushrooms are the most desirable medicines available. Yet there is practically zero interest in them on the part of Western medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. This isn’t just silly, it’s completely irrational, and I believe it stems from two prejudices: one against panaceas and the other against mushrooms, a pervasive cultural belief that, beyond adding a little flavor to a dish, mushrooms are essentially worthless.

—Andrew Weil, M.D.

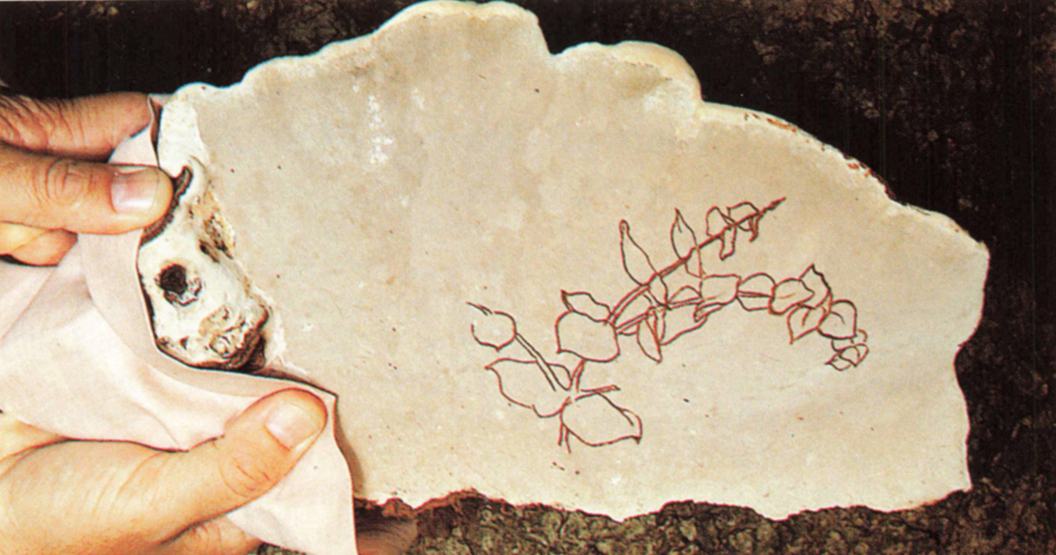

Artist’s Conk (Ganoderma applanatum)

Other Names: Artist’s Palette, Artist’s Fungus.

Key Features:

1. Mushroom shelflike, perennial, very hard.

2. Cap (upper surface of shelf) ridged and furrowed, brown to gray, not shiny.

3. Underside white when fresh but staining brown when scratched or bruised.

4. Stalk absent.

5. Growing on trees and stumps.

Other Features: Medium-sized to very large; pores on underside of cap so tiny they can hardly be seen; underside often brown in old age; spores brown or reddish-brown.

Where: At the bases of living trees, especially hardwoods, and on dead hardwoods or conifers; widespread and common.

Edibility: Much too woody to eat.

Note: There are many woody perennial conks, but this one is easily recognized by its white underside that stains brown immediately when scratched. As the brown staining is permanent, messages or pictures can be etched on it (see photo on this page), hence its popular name. It has been calculated that large specimens like the one in the above photo liberate 30 billion spores a day! Subtle air currents may lift some of the spores onto the cap, where they form a brown or red-brown powder. See MD 576-577 for more information.

The Warm Mists of October: “Of Course”

Roberto’s favorite coccoli patch has been cleaned out by an honorary Italian whose ancestors wore skirts. A woodland tryst with artist Francesca is interrupted by a marauding band of ticks. Fleeing the bloodthirsty creatures, Roberto and Francesca discover the body of Erba Cahoots, socialite and naibobess. Erba’s lover Lloyd suddenly appears and tries to strangle Roberto. Lloyd the campus animal control officer appears in the nick of time to save Roberto from Lloyd the mason’s deadly grip. A chunk of limestone found next to the victim implicates Lloyd the mason, but Lloyd the campus animal control officer has other ideas…

All eyes widened in unison as Lloyd grabbed Francesca’s wrist and clipped the handcuff shut. He twisted her around so that the cuffed wrist was behind her, pulled her other wrist back and, snick, she was in custody.

Roberto was too stunned to speak. Lloyd alertly saw his apoplexy and began his explanation.

“I’m a pro,” he said. “Trained to notice small details. One clue tipped me off. But let me construct a scenario.

“Erba knows Francesca is waiting for Roberto near his favorite mushroom patch. She goes there and tells her something that is enough to make Francesca so mad she hits Erba. Maybe she doesn’t mean to kill her, but that’s for the judge and jury to decide.

“Then she drags the chunk of limestone over to the body to make it look like someone more athletic used it for a weapon. Someone like Erba’s boyfriend Lloyd.”

“You can’t be serious,” said Francesca. “You have no reason to believe I was near here until Roberto called me over.”

Lloyd answered, “Shall I paint you a better picture? You didn’t kill her with the rock because it is too heavy for you to swing easily. What you used was the palette you were drawing on while you waited for Roberto to show up!”

She expostulated, “But that is absurd! I had no palette!”

“Oh, but I believe you did!”

With that he strode to the tree and, using a handkerchief, detached the shelflike fungus that seemed to be growing there. It came away easily, having been loosely fitted back to where it had originally grown.

He turned it over, and the other two gasped to see a picture begun on the other side.

Francesca began sobbing, not very softly. “I was going to tell Roberto I was leaving him for Erba. I couldn’t hide our love any longer. But she came here to say she was leaving me for Lloyd.”

Two lines of tears trailed down her cheeks. “I could only have been happy with her.”

The Black Maria had taken Francesca away, and the afternoon vapors began condensing into a light fog, quietly sinking to the tree tops to mantle them in a gauzy film of evanescent mist.

Roberto turned and began to leave that awful dell where his life had changed like a dark winter river carving a new channel under the pressure of raging floodwaters murky with the debris and sentiment of events back upstream.

But something bothered him. He turned back to Lloyd, still busy collecting his evidence.

“I don’t believe you finished. What was the clue that tipped you off?”

Lloyd smiled. “It was a fluke, really. My train of thought was jogged when I remembered the nickname for Ganoderma applanatum.

“Of course! Artist’s Palette.”

“Actually, that thought came later. You see, another name for that hard blunt object is, of course, Artist’s Conk.”

The evanescent mists lingered a while around the tree tops before finally settling on the dark redwood needles, trickling together, then leaping like silver orbs of light into the void ‘twixt Roberto Mortillero’s shirt and neck as he pushed back to his car through the warm mists of October.

His eye was caught by the flush of motion to his right. There, darting away, was that funny little man in the skirt again! And he was acting very suspiciously. Against his better judgment, he turned to follow…

—Luen Miller

Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor)

Other Names: Coriolus versicolor, Polyporus versicolor.

Key Features:

1. Mushroom shelflike, bracketlike, fan-shaped, or forming rosettes.

2. Texture tough: leathery and pliant when fresh, rigid when dry.

3. Cap (top of shelf or bracket) with narrow concentric zones of various colors, velvety-hairy zones usually alternating with silky-smooth ones.

4. Underside with a thin, tough sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface whitish to buff.

5. Stalk more or less absent.

6. Flesh white or pale, thin.

7. Growing on hardwoods.

Other Features: Small to medium-sized; zones on cap variable in color: usually gray, brown, and buff, but also yellow, bluish, reddish, black, white, and even green from a coating of algae; edge of cap often wavy.

Where: In groups, rows, or shelving masses on dead or occasionally living hardwoods, rarely on conifers; widespread and very common, especially in California.

Edibility: Too tough for food, but some people believe it stimulates the immune system. It can be used raw as a natural chewing gum while hiking, or taken as a tonic.

Note: This bracket fungus is a familiar feature of our oak woodlands. Several similar species occur in temperate and tropical hardwood forests; Trichaptum abietinus, with a hairy whitish cap and violet-tinged underside, is common on dead conifers. See MD 592-595 for more information.