The Institutionalization of Inequality: Pecking Orders

From the battles of cocks we can form no induction that will affect the human species.

—ROUSSEAU, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality

As we have seen, once we allow for the possible nonreciprocation of interactions, inequality is likely to arise, at least in terms of some persons having a greater number of relationships than others. While it is still possible for relationships to crystallize in such a way as to lead to overall equality, the resulting structures tend to be fragile. If inequality cannot be prevented from emerging, it may not simply characterize persons (some more popular than others), it may also characterize relationships themselves. The relationships may become antisymmetric, in that the two parties are inherently unequal; they have different “action profiles.” If this occurs, as Levi-Strauss says, we may see the development of a transitive, linear order, as opposed to some sort of circle.

Levi-Strauss was thinking of the linear orders found among many animal species including our chimpanzee cousins, structures called “dominance orders,” or sometimes “pecking orders.”1 There is admittedly some general similarity between such dominance orders and the linearity induced by a popularity tournament. As a result, it has been easy for casual analysis to maintain that we are more or less chimps in clothes, driven by the same deep-seated instincts, but dressing them up in more complicated guise—and covering them with disingenuous rationalizations. But although the production of an order of antisymmetric relationships is indeed one way of stabilizing the problem of inequality—by making inequality no longer a problem but a solution—not all inequality implies the particular structure of a dominance order.

Dominance as a relationship is special because it is intrinsically antisymmetric and hence can lead to an order (see Coleman 1960: 72). In an algebraic sense, an order exists among a set of elements {a, b, c, . . .} when there is a binary relation between any two elements, which we can denote >, that has the following four properties: (1) it is antisymmetric (for any distinct a and b, if a > b then not b > a); (2) it is reflexive (a > a; this is irrelevant for the substantive purposes at hand); (3) it is complete (for any distinct a and b, either a > b or b > a); and (4) it is transitive (if a > b and b > c, then a > c). Where the set of dominance relationships fits these criteria, we may say that a dominance order exists.

In cases where we find such a dominance order, we may also see other relationships that are “structured around” the dominance order in that they are influenced, though not wholly defined, by dominance relationships. For example, grooming among primates (an asymmetric relationship very close to donation) may be related to dominance, in that A may groom B rather frequently, and not vice versa, in large part because B dominates A. But it is not necessarily the case that B will never groom A (though B may never be dominated by A), nor is it necessarily the case that A will groom every other animal who dominates A (for an actual example, see Kaplan and Zucker 1980).

In other words, among animals, many forms of relationships may actually be structured by a simple linear dominance order, though these secondary relationships do not themselves take the form of an order. The same may be true for humans. Because the dominance order is a simple, and structurally elegant, social structure, and because it is a common feature of social life in some other primates, it is indeed reasonable to expect that we should see such orders spontaneously arising to cope with problems of inequality raised in chapter 2. And indeed, this is often assumed to be the case.

But writers making this claim generally confuse the inequality produced by popularity tournaments and that produced by dominance orders, leading to a tendency to see dominance orders among human beings where they probably are absent.2 Because they assume that human inequalities are basically the same thing as dominance, such researchers have not looked closely at actual interactions to determine whether or not this simple and potentially powerful form of social structure does in fact tend to emerge among humans. In this chapter, I wish to examine the structural properties of dominance orders among animals and demonstrate that the loose understanding of dominance orders often applied to human social life does not even apply to animals. I then turn to humans and demonstrate that proper dominance structures only seem to arise among children and mid-adolescents.

Dominance orders can arise in different ways. In one, a preexisting difference in some attribute or attributes leads to an inequality (e.g. A is “greater” than B in some respect); relations of inequality are then the scaffolding for interaction. So if all animals have some degree of individual characteristic ζ, animals i and j can compare themselves in terms of degree of ζ, with animal i submitting if ζi < ζj and animal j submitting if ζj < ζi. For example, little animals may get out of the way when big animals approach. In this simplest case, the people or animals involved observe one another to determine the direction of inequality but do not need to interact to create their order.

It also may be the case that animals cannot observe the qualities that lead one to become dominant over the other without some sort of dyadic interaction. This dynamic is somewhat like the card game “war”—each animal has some stable individual quality, but this quality is unknown until a bout with another animal in which both turn over their cards at once. According to this conception, there actually is, from the get-go, an implicit ordering of the animals, although they themselves do not have immediate access to it. Instead, they must re-create this via agonistic interactions (or, more generally, some form of “paired comparison”). For example, school children attempting to create a height order seem unable simply to arrange themselves from tallest to shortest. Instead, they pair off (at least among rough equals) to determine which is tallest, and repeat this enough times until the order is re-created.

Until relatively recently, it was assumed by most researchers that this was how pecking orders formed; the underlying individual quality might be somewhat different in different species, but the idea was the same. Every animal has some “toughness,” say; this toughness is a continuously variable quantity that is different in every animal, and so given any pair of animals, one will be tougher than the other. But closer observation of animal groups both in captivity and in the wild, and the experimental work of Ivan Chase that will be discussed below, has demonstrated that in a number of species, including some rather dim ones such as fish and chickens (e.g., Schjelderup-Ebbe 1935: 952), the formation of clear pecking orders seems to require awareness of the social pattern as a whole (see Sade and Dow 1994: 158), if only because the correlation of rank with observable characteristics (including observable “aggressiveness”) is too low to produce the kind of consistency observed (Coleman 1960: 99; Chase 1974; Chase 1980; also see Dugatkin, Alfieri, and Moore 1994). Instead, Chase and others put forward a different understanding of the production of orders.3

In this conception, bouts are necessary not simply because they allow each animal to turn over her card but because the “qualities” that determine dominance are themselves created—or at least altered—in social interaction. This may be because each individual’s latent state is changed by the results of the past bout; such a scenario is reasonable for many mammals based on what is known about the relationship between hormone levels, aggressiveness, and response to defeat. “Winner effects” refer to the increased confidence and aggression an animal experiences after besting an opponent, while “loser effects” refer to the opposite among those bested. Such effects could plausibly lead to an order in a set of animals that had originally been equal along all measures related to dominance (also see the more complex approach of van Doorn, Hengeveld, and Weissing 2003a, b).

But it is also possible that the formation of the structure is dependent on the sequence of interactions because animals observe the results of other interactions, and this affects their estimates of others’ probability of submitting to them in an agonistic situation. That is, the interaction between A and B does not simply change the future interactions of A and B, but also those of some C who happens to observe them.4 The linear order may be largely due to a combination of “winner effects,” “loser effects,” and “bystander effects” (in which those who see one hen beat another become less confident when encountering the victor and more confident when encountering the loser). From close observations of chickens, Chase actually finds that hierarchies tend to develop in the following way: two chickens have a showdown; the winner (call her A) then attacks and dominates the bystander (C). The previous loser (B) then can encounter (C), and no matter which ends up dominating the other, a transitive triad results.

This process is not the same as that witnessed among primates or among some other birds (see Chase and Rohwert 1987). There, a more complex heuristic may be used, but Chase (1982a) still suggests the possibility of the structure arising via the accumulation of local structures (including an increased probability of reversals in intransitive triads, which leads to a tendency toward transitivity).5 While this process could also lead to the production of an order in the absence of preexisting differentiation, it might simply speed up the process whereby the “correct” order (that is, one congruent with preexisting differentiation) was established (also see Beacham 2003).

Figure 4.1. Space of pecking orders

Now it may be that actually existing dominance orders fall somewhere between these scenarios—indeed, we can imagine these three conditions as poles in a space of possibilities formed by the two dimensions of the degree to which dominance is defined by comparison of stable individual qualities and the degree to which interaction is required (see figure 4.1). This space is triangular because if stable individual characteristics contribute nothing to the production of relationships of dominance, surely interaction will be required for the relation to be created. The early discussions of dominance in animals—and many contemporary ones of dominance among humans!—assumed that all cases fall in the corner on the right. Such an assumption is no longer tenable.6

This suggests that pecking orders generally require some degree of visibility—there must be some public sign that indicates to other animals that A is “higher” than B. The importance of visibility does not contradict the importance of individual characteristics.7 Both are generally involved, although the trade-off—and hence the exact position of any species in the triangular space above—depends on the species in question and perhaps the conditions (most important, captivity versus wild). There are no known cases in which dominance position is clearly totally divorced from individual attributes, but also no cases in which dominance position can be perfectly explained by measurable individual attributes.

Further, if we were to select one individual characteristic that is most commonly associated with triumph in an agonistic encounter it would be self-confidence (and not size, age, or strength per se) (see Schjelderup-Ebbe 1935: 955). Self-confidence in turn is associated with individual characteristics that—at least in the artificial situations usually studied involving the introduction of previously unacquainted animals—precede the formation of the dominance order (such as weight, age, strength). But it is also associated with position that comes out of the dominance order (e.g., mother’s rank for the case of ranked matrilines) or out of the experience of interaction that itself constructs the dominance order (e.g., “winner effects” and “loser effects”).

Self-confidence is crucial because the encounters that lead to submission rituals are generally ones that are themselves ritualized, and therefore involve restrained aggression. This does not mean that the encounter will never escalate to unrestrained aggression; on the contrary, this is indeed likely if both animals refuse to submit. This type of game—incidentally called “chicken” in the United States—is one that behooves both parties to make an accurate forecast of their own probability of triumph, since the cost of pursuing a “no-crack” strategy can be very high (on the psychology of choosing to submit, see Kummer [1982]). Animals apparently take their own sense of themselves into account (thus a maturing male will, perhaps through experimentation, sense that he is now strong enough to challenge another who has always dominated him), but also what they see around them.

We might understand the process whereby pecking orders form as follows, taking chickens as an example.8 Each chicken not only has some degree of confidence, but some guess as to each other’s confidence. Of course, they may under- or overestimate each others’ confidence, but they change these estimates as a result of the interaction whereby if one hen estimates that a second is less confident than herself, she will attack. If the attacked is actually more confident than the attacker guessed, there will be a reciprocation. The first hen may repeat the attack, or she may lose some confidence and abandon the attempt. If so, other chickens will consider the unreciprocated attack important information to help refine their estimates of the birds involved.9 Thus according to this simple model, there may be an individual-level quality that determines the outcomes of agonistic encounters, but it is one that is fundamentally tied to the ongoing social interaction.

In support of this interpretation, Ginsburg and Allee (1942) and Allee (1942: 124f) demonstrated that by “fixing” a series of bouts for mice (pairing them with others of a more or less aggressive species), one could—like Shaw’s Professor Higgins who managed to train a Cockney flower girl to assume a place in Britain’s upper class—condition a “bottom” mouse to have the confidence to move up in the hierarchy and eventually become a “top” mouse (or the other way around).

This space of possible processes that may lead to dominance structures is related to the space we saw in the previous chapter involving a trade-off between differentiation, dependence, and involution. The parallel is far from exact, for it is not the dimensions themselves that reoccur but the trade-offs. In this case, we find that the space of possibilities may be redrawn as in figure 4.2. That is, the differentiation characteristic of a pecking order must come from somewhere—either from some valuation outside the set of dominance relationships (and hence position in the dominance order is dependent), or from inside, due to the involution of relationships. This figure adds little to the previous for this particular case, but it illustrates a parallelism that will recur, namely that organization comes from somewhere, and from the perspective of any set of relationships, we may divide this into “from inside” and “from outside.”10 In this case, we are interested in a particularly vertical organization, one that militates against equality; in chapters 2 and 3 such equality or mutuality could itself be a focus of organization and introduce a set of related tradeoffs; from here onward we will see equality of any two persons in terms of what is implied by the set of relationships as a whole.

Figure 4.2. Recasting of figure 4.1

In sum, dominance orders arise when sets of agonistic contests are decided in a consistent way; consistency is rooted both in individual qualities (to some unknown degree) and to social processes of two types: first is the learning or biophysical effects that come from leaving a previous encounter a winner or loser, and second is the ability to witness outcomes of contests between other animals. This only sketches the boundaries of possibility of the dominance order; to learn about their structural characteristics, we must look more closely at well-studied cases.

Dominance orders were first discovered among poultry by Schelderup-Ebbe in the form of pecking orders (though see note 3; it is quite possible that this was known to agriculturalists previously). The pecks directed from one hen to another are clearly damaging—even the city-dweller first notices that certain hens (those at the bottom of the order) generally have a sorry, bedraggled look, due to pecks received at the top of the head. But then one realizes that as hens are generally of the same height, for the dominant hen to get in a good peck, the subordinate will actually have to lower her head slightly, or at least not raise it up. While hens lower their heads to feed, and are thus vulnerable at certain times, it turns out that they seem surprisingly willing to have their heads lowered when confronting dominant hens. This lowering of the body or just the head of the subordinate animal seems to be an extremely widespread symbol of submission in the animal kingdom. Among some of the more decent sorts of animals (e.g., cows [Syme and Syme 1979: 45f]), such a show of submission is sufficient to get one off the hook and escape punishment: among hens and similarly nasty creatures, however, this is not so, hence the bedraggled look of low-ranking chickens.

Similar structures (see Chase 1980 for a literature review) have been found in a number of other social animals, and what is crucial (I shall argue below) is that where such dominance orders are found, some similar symbolic demonstration of submission is also present. The list of animals with known dominance orders grows steadily and includes not only many herd animals (domesticated and wild) but even goes down to wasps and ants, which have a ritualized submission routine that involves lowering the head (Hölldobler and Wilson 1994). While orders can be produced in still other species by forcing competitive bouts (such as by restricting the food supply for caged animals), this does not necessarily imply that the dominance order exists as a naturally occurring form of social organization. Thus one can generate dominance orders in turtles, toads, and frogs (Boice, Boice Quanty, and Williams 1974), but no clear evidence of ritualized submission has been noted as of yet.

Because humans are generally classed as primates, dominance orders among primates have attracted the greatest attention by sociologists hoping to learn some lessons about human social organization (e.g., Tiger 1970). I shall argue against the presumed utility of this strategy below, but even if we accept the premise that examination of primates will give us a key to understand human dominance, it is hard to come up with a simple model of general primate dominance that can be applied to humans. As we shall see, research over the last few decades, while supporting the centrality of dominance hierarchies, has shattered any notion of a general linear form of dominance that is constant across species (see Yerkes and Yerkes 1935: 1019 for the classic statement). I will briefly review important results from primatology before going on to discuss what is known about humans. I will follow ethologists’ convention and call the highest-ranking animal in some dominance order the “alpha” animal, the second ranking “beta,” etc.

It is true that some form of hierarchy is common among the social primates, but it is not the case that the type of hierarchy is the same in all species. Among some, the order is clearer for males than for females, and in others the reverse is true. Among some, orders involve individuals, and in others families. For example, for gorillas and chimpanzees, the female order seems less fixed than the male order—indeed, in some cases for female gorillas there may be no consistent direction to their relationships—and females may be said both to have more quarrels but less serious aggression (cf. Schaller 1963: 260; Schaller 1964: 133; Walters and Seyfarth 1987: 312; Nishida and Hiraiwa-Hasegawa 1987: 168). But all species of macaques have a matrilineal hierarchy at the core of the society (de Waal 2001: 285). At least under some conditions, each mother has a position in the hierarchy, and immediately under her, all her daughters (with the younger generally ranking higher), all above the next matriline (Chepko-Sade, Reitz, and Sade 1989). Among patas monkeys, which (like gorillas) have large groups with one mature male each, the females tend to form a linear dominance order (Kaplan and Zucker 1980). In other species (such as the related Vervets and Sykes’ monkeys), both sexes may form a single ranking, though sex difference is preserved in that the highest ranking male may perform some of the functions frequently attached to this “alpha” position even when he submits to an alpha female (see Rowell 1971: 634, 636 for examples).11 Finally, in at least one species, the wooly spider monkey, close observation has found no evidence of a dominance order at all and an extremely low rate of agonistic interactions (Strier 1986: 244, 275).

The variability of dominance structure is related to differences in the normal social life of different species. Many primates (including most prosimians like bushbabies and tarsiers, but also the orangutan) are more or less solitary; some others form monogamous couples that forage together (examples here include certain new world monkeys and lemurs). Other groups range from large multimale groups (from the loose associations found in chimpanzees to the tighter ones found among most macaques and many baboons) to one-male groups (from the small ones of the famous hamadryas baboon to the large ones of the Drill and Mandrill baboons).12 The hamadryas baboon is structured around “families” in which one adult male has ties to one or more females (ties that are generally respected by third parties), and adult males simply do not have ranks at all. Tension is resolved by both parties submitting, for even the victor risks loss of control over females during a prolonged conflict (Kummer 1995: 167ff).

Further, even within species, particular groups may vary greatly in their organizational principles (see Strayer and Cummins 1980: 94). Among small groups of chimpanzees, the males tend to have a clear hierarchy, while in larger ones this seems to be generalized to a few orders of more-or-less equivalents (e.g. high, middle, low) (Walters and Seyfarth 1987: 311). In other cases, differences between groups cannot be so directly linked to anything so simple and generalizable as group size but may depend on the particular mix of temperaments involved (see Capitanio 2004: 28; de Waal 1977: 243, 253).

Finally, while all dominance hierarchies have some sort of signal of accepted submission, the degree of violence associated with dominance varies dramatically. De Waal (1990: 157–66) points out that our conception of dominance hierarchies in monkeys comes largely from rhesus monkeys, the most studied species, which have strict rankings that are enforced with serious bitings (for an example of the perfect ordering of dominance relations among rhesus monkeys, see Sade 1972: 207). But the closely related stumptail macaque has a more relaxed rank system (e.g., subordinates will initiate contact with superordinates) and “punishments” by the superior animals tend to be painless rituals such as giving a mock bite on the wrist (and subordinates may defuse tense situations by offering a wrist for such a ritual bite). Thus even within closely related species of primates, there are many different forms of dominance orders, and if we attempt to extract implications for humans through simple analogy, the lesson we learn will appear quite different depending on the case we choose. However, there are also commonalities that shed light on those qualities of the relationship of dominance that have structural implications.

For one, it is clear that while size and aggressiveness are frequently useful in allowing one animal to assert dominance over another, dominance in general cannot be equated with a single individual attribute or even with a set of them (see Bauer 1980: 107). Thus de Waal (1998: 77f) discusses how to a naïve observer, it seems obvious that a particular chimpanzee is at the top of the dominance order because he is the biggest and strongest, but things really go the other way—the alpha puffs himself out and walks in an exaggerated way, while others, in submissive greeting rituals, make themselves look low and small.13 While there is a general inverted-U shape curve relating dominance and age in many species (see, e.g., Nishida and Hiraiwa-Hasegawa 1987: 175), even age, size, and physical condition considered jointly do not wholly determine rank.

While individual attributes are important, an animal’s position in this hierarchy generally expresses a balance of power in the group as a whole. In particular, among some species (most importantly chimpanzees), position in the dominance hierarchy is a function of alliances as well as individual qualities; further, position in this order does not unproblematically translate into agonistic triumph in any particular encounter. In particular, alpha males often depend on female support (well-studied examples involve chimpanzees and different types of macaques [Smuts 1987b: 409f]).14 If others can support, they can also undermine: De Waal (1998: 44; 2001: 282; also Goodall 1990: 46, 71) gives instances in which the whole group turns on the alpha male and sends him fleeing, in some cases permanently removing him from the position, indeed sending him from the top to the bottom (also see Kummer 1995: 301f).15

Not only can dominance relations be due to systems of relationships (e.g., alliances) transcending a dyad, but these other relationships may themselves be structured. In other words, there are other forms of social organization that have (until recently) largely been overlooked (at least in the West [de Waal 1998: 137]). The best known is the male-female “friendship” studied among baboons by Smuts (1985), but horizontal relations connecting coreared infants may also cut across the lines established by a dominance order. There are also cases in which, at least among the more dominant members, there seems to be what de Waal (1998: 207; cf. 1987: 426) calls “a network of positions of influence” apart from the dominance hierarchy. Finally, Sade et al. (1988: 410), noting that monkeys have more than one status because they have positions in more than one network, put forward and examined a dimension of centrality that is partially independent of dominance status.

Further, there may be some degree of slippage between alpha position and leadership, which may (in the fashion famously proposed for small groups by Bales) be differentiated. De Waal (1998: 145f) describes a situation in which a young male became alpha with support from an older ex-alpha, but did not adopt the peacekeeping aspects of the alpha role, which seemed too difficult for a neophyte. Instead, the ex-alpha performed this role and was rewarded by being given preference in greeting by other group members, though he himself would defer to the new alpha. Kummer (1995: 53f) not only describes a similar divorce of dominance and leadership among baboons, but also the case in which the alpha position is taken over by a female (also see Stammbach 1987: 119).

Not only can there be a differentiation between dominance position and leadership, but positions in the dominance order are more labile than the term order suggests. The dominance relation between any two animals A and B may depend on the presence or absence of other animals. This is certainly the case for infants of many species—they have two ranks, one that is “their own” and another when their mothers are present that comes from the mother’s rank. But this phenomenon often determines the relationships between adults as well: it is possible for some A to dominate B when C is present but not when C is absent. (Among Bonobos, the mother’s rank influences the rank of males well into their adulthood; see Furuichi [1997].) We will return to this later when we examine how primates take the dominance order as a backdrop for action.

The dominance order, then, is not equivalent to the social structure of primate groups involved. Other relations (such as kinship and friendship, perhaps even coparenthood) also exist in at least some species, and the structure of any specific relationship (such as grooming) may make reference to these other relations and not simply the dominance order.16 The pecking order is indeed a distinct structural form, but it is easy to overstate the conformity of existing groups to such an ideal typical order. With that caution in mind, we go on to explore the properties of dominance orders in animals and how they channel action.

To summarize, we may say that a dominance or pecking order only arises where there are (a) frequent agonistic interactions that are (b) always resolved by an act of submission by one party (see Bernstein 1980: 80), and (c) the pattern of these submissions is mutually reinforcing. As we have seen, (c) entails that the relation in question be antisymmetric, transitive, and complete (cf. Hage and Harary 1983: 79).17 These three conditions imply that the structure is an order in the algebraic sense.

Condition (a) pertains to the content of the relationships (agonistic interaction) and (c) to the nature of the form (an order); this seemingly complete specification makes it easy to ignore (b) as a crucial aspect of pecking orders (that is, the process). Yet it cannot be accidental that in all or almost all cases of known dominance orders, these confrontations involve ritualized submission (see de Waal 1987: 422–24), in which one animal signals defeat by unambiguously refusing to defend or attack, often presenting him- or herself in a physically vulnerable position, at which point the other animal ceases all physically dangerous aggression (for a general statement and analysis of the case of rhesus monkeys, see Bernstein and Gordon 1974: 306). It is easy to understate the importance of this, because we often assume that individual qualities (e.g., size) are all that is needed to produce a pecking order. But as this assumption has been shown to be false, we would do well to look closely at the relation of ritual to structure.

The idea of ritualized animal behavior sounds somewhat strange to modern ears, although it was taken for granted by early sociologists. In volume 2 of the Principles of Sociology, Spencer (1910 [1886]: 3, 34, 116, 220) began by analyzing ceremony and started with animals: for example, the dog crawls on its belly to indicate submission, and “a parallel mode of behavior occurs among human beings.”18

Despite this bold beginning, there has been surprisingly little attention to ritual in animals among sociologists, perhaps because of an illogical belief that purely communicative action could not be reconciled with natural selection, since there is no advantage to evolving a symbolic display if others have not already evolved the ability to interpret it. But there is no contradiction, as Darwin himself understood—many ritual behaviors seem to be prolongations of intention movements, behaviors that precede an action. It is reasonable to expect that other animals will already have understood the “meaning” of such a functional gesture as opening the mouth to bite, for, as Mead (1934: 49) says, in uncharacteristically clear language, the meaning of a gesture is “what you [the observer] are going to do about it.” Mead’s example of a gesture that communicates meaning is the growl of an angry dog which “means” that the dog is aroused for possible attack. All the evolving animal need do to produce purely ritual behavior is to make use of the preexisting “meaning” of preparatory actions or intention movements by prolonging them and separating them from the action itself. The meaning need not be known to the animal making the gesture for it to be reinforced via selection. The dog who growls for some time before attacking may be the dog that does not need to attack; the crab that holds his claw open in front of his eyes for some time before pinching may be the one that never needs to pinch . . . and therefore is less likely to be flung against a rock (also see Wilson 1975: 224).

We are justified in calling the gesture that has been exaggerated, and is performed in the same way in the same circumstances because of its communicative value, a ritualized one. There are a number of different forms of such communicative ritual, but submission rituals are quite common in the animal kingdom. Many of these involve the submitting animal making itself physically lower than the other. These rituals are more likely to exist where animals live together in permanent or near-permanent fashion. Thus male rhinoceri and other ungulates that have a territorially based system of dominance (in which one male is dominant over a fixed area and other males either accept this dominance, stay off, or challenge) may have agonistic encounters, but these can end with the loser simply turning and running when it seems prudent to do so.19 It is not necessary to publicly advertise this fact, since there is no “chorus” of bystanders who need to keep tabs on the relative positions of the two. Ritualized actions serve to make the outcome of a dyadic contest unambiguous and hence help avoid the necessity of its repetition.

Significantly, such ritual is not observed in animals that do not form dominance orders in the wild though they can be induced to by malicious experimenters who force them to compete for food. Thus box turtles will displace and bite each other, and occasionally hide in their shells, but do not necessarily submit (here see Boice 1970: 707). Retreat into the shell on the part of one turtle does not inhibit further aggression by another, and rightly so—that first turtle may reemerge and continue the fight. Further, even among primates with dominance orders, those that seem to lack a vocabulary of appeasement gestures have less rigid orders, and the combination of low general levels of aggression but serious damage when fights do take place that suggests an absence of inhibition on intragroup fighting (see Rowell 1971: 628–30).

It is not our place to speculate on the reason for the existence of such rituals here. But it is important that these rituals allow for a public signaling of the outcome of an agonistic contest, and it is these signals that determine the dominance order. Indeed, while it may go against the realpolitik assumptions of social scientists who pride themselves on their unsentimental perspective, the dominance order is better understood as the order of these ritualistic signals than as a matter of force and its results, since in many species (including chimpanzees), it is these rituals (and not necessarily the more physically important fights, displacements, or food-taking behavior) that take on the form of an order. Other interactions are only probabilistically related to position in the dominance order, and hence there may be “reversals” in terms of the outcome of fights, in that a low-ranking ape will best a high-ranking one (e.g. de Waal 1977: 233, 235).20 But there are no reversals in greeting rituals. As de Waal (1998: 81) says, “Greeting reflects frozen dominance relationships. It is the only form of social behavior that is [perfectly antisymmetric among primates].”

The essence of the pecking order, then, turns on the ritualized submission relations of the animals in question. The dog, as Spencer noted, crawls on its belly; submitting rats roll on their back and allow the dominant to rest its paws and head on the first’s exposed belly (Baenninger 1970). These submissions are mutually reinforcing in that the animals can be more or less ranked in an order of dominance. But the order may be more than either an analysts’ construct or a built-in genetic program that the animals are helpless not to recreate. It can be, and certainly is in the case of the higher primates, perceived as a “social fact” by animals who take the existence of structure into account and adapt their actions accordingly.

Now it is not clear how animals understand the pecking order; almost certainly, it varies by species. The pivotal question is whether each animal in a group of N remembers N-1 bits of information pertaining to each relationship it has with each other animal, or whether it remembers N ranks of individuals, or even statuses (that is, interval level as opposed to ordinal level distinctions). Given a perfect ordering, remembering ranks or statuses is superior in that at the simple cost of remembering one additional piece of information (although far more complicated information than the binary value of submit/dominate), the animal is able to re-create the relationships of all other pairs of animals, which allows for far more subtle interactions. As we shall see, it is impossible to explain the actions of animals of more intelligent and social species unless we posit that they have some sense not only of their own position vis-à-vis other animals, but of the order as a whole.

Such a sense of the social structure is seen, first of all, in the fact that in many primates and some birds the highest status animal is not merely able to dominate all others, but seems to fulfill some qualitatively different role. For example, among some old world monkeys, the alpha male—and not others—will respond to a stranger who presents a group threat (Bernstein 1964, 1966). Furthermore, the alpha may intervene in disputes on the side of the lower-ranking member or simply enforce the peace. Now to some extent, this may be a general feature of high rank (as opposed to a special position for the highest ranking), since in some species, higher-ranking animals are “loser supporters.” Among poultry, the relation between any two birds is well predicted by their rank difference—the highest ranking hen will peck the lowest with the greatest intensity and savagery. But among more social (and intelligent) birds such as jackdaws, animosity is reserved for those who are actually potential rivals; the more dominant intervene in a struggle between two lower ranked birds consistently on the side of the lowest (Lorenz 1952: 148–50).21

But alphas do not merely support losers, they may suppress fighting, especially in multimale primate societies. Among chimpanzees, the alpha may keep order by breaking up fights according to the simple but effective principle, “hit anyone who hits.” This generally means hitting the winning party who is less pleased with the premature end to the contest. (This is all the more notable because adult male chimpanzees tend to be winner supporters [Smuts 1987b: 404]). But even outside of such a melee, the alpha is likely to become a loser-supporter or protector (see de Waal 1977: 260, 263 for the case of Java monkeys [Macaca fascicularis]; de Waal 1987: 427; de Waal 1998: 117, 146). One need not see noblesse oblige in this action, nor any special altruism—while the alpha male may suppress conflict when he intervenes on the side of the loser, he can dramatically escalate it when he intervenes on the side of the winner (de Waal 1977: 265). The point about the alpha’s intervention is not that it indicates that he occupies an altruistic role, but that there is a role at all.

The tendency for alphas in some species to be loser supporters suggests that the animals in question are able to cognize a sense of the ranks of others. We also see evidence of animals understanding each others’ ranks in the fact that in some species, animals tend to fight more with those close in rank to themselves (see Bernstein 1969: 457; Bernstein and Gordon 1974: 308; Kummer 1995: 294), while in others, they seem to have more of their friends from these close rank positions (Rowell 1971: 637).

But this very strength of the pecking order—its ability to seem a socially objective “thing” in which all animals have fixed places—can undermine it. Once animals can in some way treat ranks as social givens, they can then orient their action strategically to this social structure. Instead of the social structure simply being the outcome of unreflective (if socially influenced) sets of interactions, the social structure can be part of the environment taken into account by animals as they act. Returning to the imagery of the dialectic of institutionalization with which we began, the dominance order emerges as a reified institution—“frozen” action, as de Waal interestingly called it above—that can confront spontaneous interaction (just as Simmel would have said) as an objective fact.

The most direct form of such second-order interaction is the alliance. In an alliance, one lower-ranking and one higher-ranking animal form what is in effect a mutual defense treaty. Now of course, this can be folded back into the dominance order in the form of raising the rank of the subordinate member. So if the sixth ranking forms an alliance with the second ranking, this may allow the sixth to move up to fifth rank. Indeed, early analyses tended to assume that all such alliances were folded back into the linear structure. In some cases this does occur: certainly lasting alliances among chimpanzee males can lead to changes in rank position.

But in other cases, alliances can lead to mutations of the dominance order. In what is known as “dependent rank,” one animal may rank sixth when the second-ranked animal is not present and fourth when the second ranked is present. (In contrast, the ranking that arises from paired comparisons may be called the “basic rank” [Kawai 1958].) Far from being a minor complication, this more complex state is the one that determines behavior in most circumstances (at least in naturally occurring communities), may be prior in the life of each individual (because in many species infants originally take rank from their mother [Kawai 1958: 112; Bernstein 1969: 456]), and is often quite different from the basic rank (de Waal 1977: 226). While this dependency is often most clearly seen for the high-ranking females whose rank is tied to that of the high-ranking males (this is seen in a number of monkey species as well as Jackdaws [Lorenz 1961; de Waal 1977: 227]), or children of high ranking females (de Waal 1977: 242, 274; Sade 1967 on rhesus; McHugh 1958 on bison), it is also generally true for adult males, who, as Nishida and Hiraiwa-Hasegawa (1987: 175) point out, rarely interact without others present.22

As the preceding makes clear, formal ranks in a dominance order do not need to correspond to the actual ability to triumph in agonistic situations; this latter ability depends on situational factors including social alliances. While long-term changes in these factors can indeed lead to a change in position in the dominance order, it is not at all unusual for there to be a relatively long period in which the ritualized submission relations do not correspond to the outcomes of nonritualized contests (e.g., fights). This is true even with (perhaps especially with) the alpha position. Indeed, just because the alpha position is one that seems to be a “position”—a role divorceable from the individual who occupies it—there can be a difference between the power that would seem appropriate to the position and the power of the animal occupying it.23

Further, in contrast to the facile assumptions made by some sociobiologists, intrasex dominance does not necessarily translate into reproductive fitness (Smuts 1987a: 389, 395f, 398; Smith 1994: 232; also see Qvarnström and Forsgren 1998; Takahata 1991: 133).24 Where there are a number of mature males present, such as in chimpanzee groups, the alpha male does not “own” all females, who may prefer to mate with other, lower-ranking males (often those who are new or less aggressive to females, or those who are older and have ceded dominance to younger upstarts) (de Waal 1987: 429; de Waal 1998: 169; Streier 2000: 166).25 Indeed, among some Lemurs, no correlation has been found between position in the intermale dominance hierarchy and reproductive success during breeding season; the same goes for female blue monkeys, which tend to have a very linear hierarchy. While individual female hamadryas baboons have transitive preferences when it comes to choosing males, they do not agree with one another in their preferences and these preferences are unrelated to rank orderings among males (Kummer 1995: 190; Cords 2002: 303).

We have seen that any view of dominance orders as rigid sets of rules for robotic animals is unlikely to account for the range of behavior displayed by the higher primates. The very importance of the order in structuring social life means that it can provide the backdrop for strategic manipulation. Those ritual signals that are the heart of the order can be feigned or suppressed.26 Alliances cannot only affect position in the order, they can fracture it; instead of seeing this as a disturbance of an otherwise linear system, we can follow de Waal (1977: 271) and insist that dominance relations must be understood as intrinsically embedded in a more complex social context.

Accordingly, even if we accept the centrality of dominance and ritualized submission behaviors, we cannot conclude that the resulting structure of relationships will be linear under all conditions (Deag 1977: 472). Indeed, there is evidence of horizontal differentiation. For example, among Java monkeys studied by de Waal (1977: 233), one-third of the possible relations of submission in one group, and 44 percent in the other, were simply not observed at all, despite the audio- and video-taping of seventy hours of interaction (both groups combined). Thus one of the most important parts of the definition of the order—namely that a relationship exist between all interactants—may not hold for medium- and large-sized groups (also see Sade et al. 1988: 410). Even in smaller groups, it sometimes appears that three levels of dominance arise, with little to differentiate between members of the top, middle, or bottom levels (see, e.g., for monkeys Rowell 1971: 638; for apes Bygott 1979: 415, 417). Other close examinations of primate social structure have found what appears to be a combination of wholly vertical orders and horizontally differentiated organization (see, e.g., Nishida and Hiraiwa-Hasegawa 1987: 172).

Finally, and perhaps most disturbingly, there is increasing evidence that much of the dominance behavior first understood as inherent to various species may be specific to conditions that were deliberately created by humans in order to simplify the task of observation. Captivity is only the most obvious form of such altered context. The point is not that “naturally” some primate species is “nice” and only becomes “nasty” when jailed. It is that human observers tend to force a reorienting of social priorities. Ethologists make a distinction between the “contest” competition in which two animals face each other over a resource that only one can possess, and the “scramble” competition that results when animals compete only indirectly by attempting to independently gather as much of some resource as they can. The latter is common when some resource (e.g., food) is scattered about widely and commonly—it would be inefficient to waste time in an agonistic interaction with an opponent who possesses some resource as opposed to gathering it on one’s own.27

Different species rely on different foodstuffs, but even members of a single species may at different times or places find their staples to be more or less clumped in space. And the greater the clumping, the more agonistic interactions are observed (see Wilson 1975: 244, 249; van Hoof 2001; Isbell and Young 2002). (There can also be scramble competition for mates, which is associated with lower interspecific conflict [Strier, Dib, and Figueira 2002].) Unfortunately, the breakthrough in observation of primates in the wild occurred when Jane Goodall began leaving piles of bananas outside her tent for the local chimpanzees. But Goodall eventually recognized that this affected the behavior of the apes—the availability of a high quality and tasty food source led the chimps to move in larger groups as opposed to dispersing, and the males became increasingly aggressive. Eventually interspecific conflict developed between chimpanzees and baboons, species which had previously largely ignored one another (Goodall 1988: 66, 140–43, 208). Further exploration has demonstrated that some observed behavioral patterns related to dominance, once thought to be innate to a species, were unique to or exaggerated among provisioned or captive populations (see Chapais 2004; Strier 2000: 22; Strier 2003: 6). Increased agonism is one of these (Rasmussen 1988: 324; Kummer and Kurt 1967).28

In sum, it appears that dominance orders among primates involve three things. The first is a symbolic capacity leading to widespread evolution of ritualized submission behaviors. The second is a set of agonistic conflicts that lead to antisymmetric dominance relationships. The third is a particular kind of caging that leads to the completeness of the relationship. Such orders are special cases of a more general class of partial orders of dominance (cf. Iverson and Sade 1990), the increased linearity and completeness emerging in small multimale groups of patrilocal primate societies, between matrilines in matrilocal primate societies, and when the degree of agonistic interaction is increased by contest competition, especially for concentrated, high-energy foodstuffs.29

Interestingly, this deviation from a pure ordering is what Schjelderup-Ebbe first found among hens, although his article is more often cited than read (though Koffka 1935: 669 notes the horizontality and sees its relevance for human organization). But while the set of relationships may not form a simple order, the dominance structure is of crucial importance in determining the nature of social interaction in these species. It is not surprising that many analysts expect a commensurate importance among humans (see, e.g., Tiger 1970: especially 297). I will go on to question this.

No two people can be half an hour together, but one shall acquire an evident superiority over the other.

—SAMUEL JOHNSON, ca. 1766.

Chase (1980) began his pathbreaking discussion of dominance hierarchy by wondering why the same structure formed in both animals and persons. Given the results of the study of dominance in animals since then, however, the question might be asked another way: not why are there dominance hierarchies in humans, but why are there so few?

Of course, just because some behavior pattern is common to nonhuman primates, it does not logically follow that it must be suspected as innate to humans as well.30 Certainly, the variation that we have seen across primates means that even if some of the requisites for the production of dominance hierarchies are present in humans, there is no one implied social structure. Further, it has become increasingly fashionable to argue that humans have some fundamental behavior patterns that come not from their common primate heritage (which would be very long ago, before the split between old world and new world monkeys) but from presumptions as to the nature of life in the early period of recognizably human existence (e.g., the Pleistocene).

But as Christopher Boehm (1997 and references therein) has recently argued, what is distinctive about those contemporary hunter-gatherers that most evolutionary psychologists assume are closest in social life to our neolithic ancestors is their suppression of dominance, and he postulates that among early humans, “the group as a whole kept its alpha-male types firmly under its thumb, instead of vice versa.” The means of this suppression was moral sanctioning, which, though to some degree present in chimpanzees, is greatly facilitated by speech.

Boehm’s re-creation is of course simply that; what is crucial is that his comparative perspective casts doubt on the crucial premise of facile equations of dominance in modern societies and dominance among apes that provokes researchers to extrapolate from the one to the other by simply drawing a straight line between the two points. Just as Hobbes created a state of nature based on his experience of anarchic seventeenth-century England, and this model was then (by others) imputed to our ancestors, so evolutionary psychologists tend to create a model based on their own society without sufficient comparative checks. If these are done, Boehm (1997: 347, 330) notes, one finds that foragers and most nonstate people are egalitarian: “Relations between males seem to be far more co-operative and cordial than competitive and agonistic.” This is not because, thinks Boehm, humans do not have innate drives to dominate others, but because of the particular group structure that arises with foraging: if a faction develops but fails to take control it will split off, allowing the group to maintain moral consensus. Where people are more caged as Mann (1986) says, such consensus is weaker and hence control over potential dominants by the community weaker as well. Even if humans have an innate drive toward dominance, either as an end in itself or as a means to other desired ends, there is no reason to think that it leads to the particular structure of dominance orders.

Thus the prevalence of dominance structures among other primates need not make us assume their presence among humans—this is an empirical question. But answering this question is perhaps more difficult than it first appears. Consider Johnson’s aphorism above, which expresses a conviction held by a number of social scientists. It is interesting and typical that Johnson did not specify whether the superiority would be evident to both parties, to only one, or to an outside observer (or some other combination). It is not very convincing if it turns out that the superiority is only evident to an observer such as (the committed antiegalitarian) Johnson himself. Nor is it convincing if the superiority is evident only to the superior party (as opposed to the subordinate, crucial to the ritual aspect of dominance orders among animals).

Thus some sort of consensus as to the result of these quality-tournaments is necessary. But I would confidently wager that after a half-hour with Voltaire, Johnson would believe himself superior (or at least convince himself he so believed),31 while Voltaire (who once referred to Johnson as a “superstitious dog”) would be convinced of his own superiority. And—this is most important—neither would ritually signal inferiority to members of the public.

Yet human beings do seem to have ritualized submission behaviors, many of which are probably found across most cultures; further, these ritualized submission behaviors are related to those seen in animals. (Examples are looking down and away from, raising shoulders, etc.) Other actions may also signal status difference (e.g., higher status people initiate touch with lower status people who accept this; higher status people in at least some circumstances interrupt lower status people;32 lower status people may accommodate their vocal frequencies to those of higher status interlocutors [Gregory and Webster 1996]). Humans seem to be as good as fish at guessing the probable status ranks of others given their behavior (e.g., Ridgeway and Erickson 2000), and there is good reason to suspect that humans’ endocrine systems would do well at producing a linear hierarchy, by contributing to “winner effects” (that is, the impulse to win a future agonistic encounter increases with each win) (Kemper 1990).

As a result, it is not completely far-fetched to imagine that an acute observer would be able to determine the presence of a dominance hierarchy among a set of individuals on the basis of behavioral patterns that the individuals themselves do not fully recognize. Unfortunately, sociology is not in a position to make a contribution here. There has been a serious resistance against any kind of observational analysis of human social behavior akin to what is found in studies of animals (though see McGrew 1972).33 As a result, it is simply not known whether most interactions between adults produce a dominance order that could be ascertained by behaviors such as staring as opposed to looking away, touching, or interrupting. Thus the existence of such orders, though in no way demonstrated, cannot yet be unambiguously ruled out.

Of course, even if it were ascertained that there are such shadow dominance orders in social life, these would still probably be quite different from the dominance orders among other primates where the order is explicit and unambiguous. Consequently, I will proceed by assuming that we can safely count most adult groups as not having orders of the form we have examined above.

In opposition to this conclusion that dominance orders are quite rare in human life, some have argued that they are in fact ubiquitous. Such arguments, however, have generally referred to some form of ranking, which is not the same thing as a dominance order. People can frequently be ranked, but this does not necessarily have any clear implications for social interaction. Most important, the antisymmetric relation that is effectively induced via the popularity tournament is not the same as the relationship—the profiles of interaction—that actually structures the group. That is, we may say P(A) > P(B) where P(A) is the popularity of A, etc., but this does not mean that there is an actual relationship of dominance between A and B. A and B may never interact at all; the actual relation in question may be wholly mutual (perhaps either they play basketball together or they do not). It is possible for a relationship “gets along with on terms of absolute equality” to induce a very severe ranking of persons in some group, from those who “get along with” the most others “on the basis of absolute equality” to those who “get along with” the fewest.

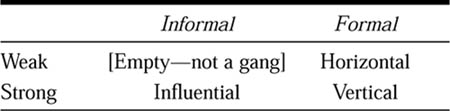

It is also not the case that differences in power or wealth translate to pecking orders: as Collins (2000) has stressed, there can be a great difference between these inequalities and the “microsituational” inequalities that are relevant for dominance orders. For one, the presence of power relations does not imply a dominance order if relationships are not transitive (cf. Spencer 1910 [1896]: 480). Finally, even given transitivity, a dominance order may not arise if there is some sort of horizontal differentiation that allows some pairs of persons not to enter into the agonistic interactions that would lead them to assume a linear order (a case which we explore in the next chapter).

In sum, although one must leave open the possibility that humans give off subtle signals that could allow us to arrange them in a linear order, adult humans do not consistently organize themselves into dominance orders such that there are repeated displays of ritualized submission that form a transitive ranking system. Since people have the cognitive ability to understand transitivity, and the symbolic ability to signal ritualized submission, and (so far as we can tell) they are not entirely peace-loving and egalitarian by nature, one wonders, why not? I will begin by considering common answers, and then make a slightly different proposal.

A common answer has been that human society involves some sort of differentiation (see White 1992). Initially satisfying, this response runs into troubles. The simplest version of this argument is that humans can get away; dominance orders may be seen as requiring the absence of exit. But while too many initial observations were made of animals in captivity, dominance orders or at least partial orders have now been affirmed to be present in primates in the wild; really, as Mann (1986) has said, what is distinctive about civilization in the long-term perspective is that it “cages” humans. Exit is easier for adults in many of the primate societies that have the clearest dominance structures than it is for most adult humans, and indeed the form of social organization of such primates is often called “fission-fusion” bands, because of their tendency to temporarily compose larger aggregates out of smaller segments that can detach themselves and go their separate ways later.

A modified version of the differentiation hypothesis holds that at least with adulthood, persons interact in a number of different settings or fields that have different principles of stratification; to the extent that these are cross-cutting, it is impossible to have the kind of submission responses that require that the subordinate party debase him or herself (since this same submitting person may be dominant over the other in a different setting). This seems quite reasonable, but runs into three comparative problems. The first is that there is no historical or anthropological evidence of true dominance orders in nondifferentiated societies; though some of these societies are highly stratified by rank, the combination of agonistic encounter and ritual submission is apparently not an aspect of their social life. The second is that there is no reason to think that chimpanzees (say) do not have distinct skills. The third is that school-age children (as we shall see below) are somewhat likely to form dominance orders.

This last finding is often believed to be consistent with the differentiation hypothesis, as it is assumed that adult life is more differentiated and complex than that of children. While it may be true that students in the elementary grades in U.S. public schools see the same set of twenty to thirty children every weekday for ten months of the year, this does not seem very different from the normal work experience of an adult. By middle school or junior high school, students may be going to different classes with different teachers and different students, and experiencing a daily degree of social variety far surpassing that of the average adult.

There may indeed be something distinctive about children and adolescents that leads to the production of dominance orders. However, it seems unlikely that the nature of this crucial factor can be determined by simple armchair reflection. A more promising tactic would be an empirical exploration of those dominance orders that do arise among children. Fortunately, there is fair amount of detailed research into such orders, to which we now turn.34 I will concentrate on one particularly rich study by Savin-Williams, which produced raw data that can be reanalyzed, though supplementing the conclusions with the findings from other studies.

Many different interactions can be used to determine the direction of dominance relationships between children (such as who ends up with a disputed toy), but just as with animals, it seems that the key is the public signaling of submission through some sort of ritualized behavior. Thus in an examination of preschool children, Strayer and Strayer (1976: 984f) found around 25 percent of the total number of initiated agonistic interactions (here looking at physical attacks and threat gestures only) were in the “lower diagonal” of the arranged matrix—that is, were initiated by a lower-ranking child against a higher-ranking child. That is, there were too many attacks going “the wrong way” for us to conclude that a true dominance order was present.

But such data can be confusing due to differential aggressiveness which may be to some extent independent of differential dominance (if some children initiate agonistic dyadic interactions but do not triumph) (Strayer and Strayer 1980: 149, 154ff). Frequently a subordinate child would initiate an agonistic action as part of a sequence that would end in his or her submission, giving a misleadingly pessimistic quantitative impression of the degree of fixity of the order. We can better understand the linearity of the structure if we concentrate on dyadic interchanges that end in a submission response (even if it is only flinching). Then we find that for the above mentioned data, only 8 percent of the total agonistic encounters that ended with a submission display went against the grain.

Such data seem to suggest that true dominance orders or near-orders do form among children (also see Sluckin 1980: 164ff). This is probably especially true for smaller groups—in larger groups, linearity may decrease as one moves away from the top positions (see Barner-Barry 1980: 183). Yet other studies have not confirmed the centrality of dominance in similar settings.35 Thus (perhaps as with the primates we reviewed above), we should simply say that dominance orders can arise among children. We want, then, to look closely at the environments where we do find evidence of such orders (understanding, of course, that not all environments have been subjected to the same attention), and also to examine the nature of existing dominance hierarchies. What actions actually characterize dominance relationships, and more simply, what personal attributes are associated with dominance rank? If, for example, dominance behavior generally takes the form of physical pressure, and stronger individuals are dominant over weaker, we will be led to one particular—and particularly simple—explanation of why and where dominance orders are likely to arise.

But just as with animals, it turns out that we must reject any facile equation of position in the dominance hierarchy and specific qualities possessed by children or young adolescents. It is true that dominant boys tend to be more athletic than are the nondominant—and this is also true for girls, at least in the camp studied by Savin-Williams. (Savin-Williams studied four groups of mid-adolescent boys, four groups of mid-adolescent girls, and then some older adolescent boys and girls. My discussion will focus on the more detailed evidence regarding middle adolescents.) But children often dominated others who were taller and heavier, even those who could beat them in a fight. In such cases, the subordinate child, though stronger, could not adequately defend him-or herself against more common means of asserting dominance such as ridicule (Savin-Williams 1987: 53ff, 76, 183f; cf. Adler and Adler 1998: 39; though compare Weisfeld, Omark, and Cronin 1980: 206 who find a strong correlation between dominance and “toughness”).

Not only is there no unique basis for achieving a position of dominance, but (as with animals) there can be a dissociation between dominance position and “popularity” (although less so, it seems, for girls than for boys). Other boys may be more popular than the alpha precisely because they are nondominant and do not antagonize others or prevent them from having influence in group activities. Similarly, popularity may decrease as a boy’s dominance rank increases over time and vice versa (for examples see Savin-Williams 1987: 111, 120, 64, 405; for a similar case among baboons see Kummer 1995: 49f).36

We found evidence above that higher primates understand the relative positions of different animals within a dominance order; the same is true of children and young adolescents. Indeed, when we turn from apes to children, we are able to explicitly ask our subjects about their own and others’ positions (Savin-Williams 1977: 403; Savin-Williams 1987: 193). For the young adolescents introduced above, explicit reports as to the ranks of others were collected, and they agree rather well with observers’ reports (although there is somewhat of a tendency for the boys in the Savin-Williams study to overrank themselves).

More important, the children then take this “objective” circumstance into account when acting; that is, they cognize these positions and act accordingly. This may most easily be seen in the fact that (at least among boys), the highest-ranking child has a qualitatively unique position. For example, he may coordinate action or resolve quarrels between others (Savin-Williams 1987: 67, 180).

There are other indications that action took place within the established dominance order. Savin-Williams (1987: 66, 112) reports for one group he studied that children tended to interact more with others close in dominance, and that best friends were twice as likely to be adjacent in rank as expected by chance. But this is not a simple case of homophily (like liking like), for the children also had more agonistic contests with those closer in rank. Supporting conjectures made by Homans (1950), it seems that children tend to interact more with those close in status, and they tend to have more conflicts with those with whom they are in reasonable competition (also see Missakian 1980: 408). In other words, they approximate the jackdaw pattern, and not the poultry pattern.

To examine this, we can conceive of each child having a position on a single vertical dimension; application of the Bradley-Terry (1952) model for paired comparisons can be used to retrieve a latent status score for each person.37 In this model, we assume that each child has some interval-level position on a single continuum of status, and the odds that A will triumph over B is proportional (in the logarithmic metric) to the difference between A’s status and B’s. Thus not all “adjacent” pairs of children are really the same distance apart—if A only wins 60% of the agonistic confrontations with B, he will be judged “closer” in status to B than if he won 90% of these contests, even if in both cases A and B are third and fourth in rank respectively.

Application of this model to Savin-Williams’s data allows us to examine whether adolescents are more likely to have dominance interactions with those close in status to themselves; the answer appears to be yes. Since ego is then more likely to triumph in an agonistic encounter with alter the greater the status difference between ego and alter, but less likely to have the encounter in the first place, there is a curious relation between the distance in status between ego and alter and the number of “wins” of ego over alter, as can be seen in figure 4.3.

Here the dyads are ordered from those with the most negative status difference (that is, ego faces an alter of much higher status) on the left to those with the most positive status difference (ego faces an alter of much lower status) on the right. The vertical line indicates the midway point where ego and alter are of the same status. Only the relative ranking of the dyads is preserved, and not their interval-level difference, so that we may smooth the resulting data to produce a simpler picture. The shape filled in with squares indicates the total number of dominance conflicts between ego and alter (“bouts”). This shape is symmetric around the line of no status difference since every dyad is counted twice, once from ego’s and once from alter’s perspective. The lower shape filled with diagonal lines is the number of agonistic contests that ego won (the difference between this shape and the former is the number won by alter). As we can see, the proportion of bouts won by ego certainly increases with ego’s status advantage, but the gross number levels out quickly. This is because the number of conflicts peaks when ego and alter are of moderate inequality.38

Figure 4.3. Agonistic interactions by status difference

This can be demonstrated more rigorously as follows: we can attempt to predict the number of bouts given the status difference (here making sure to count each dyad only once). Doing this leads to a relatively large negative coefficient, indicating that as ego’s and alter’s status difference goes up, the number of bouts goes down.39 But this effect turns out to vary over the three measurement periods—it becomes increasingly negative over time. In other words, as the summer progressed, children became less likely to enter into conflictual relations with those far apart in status from themselves.

In sum, most examinations of the development of dominance orders in children have been exclusively concerned with the ordering of the children and the proportion of conflicts won and have ignored where the interaction takes place. The child of very high status may be almost sure to win all agonistic encounters with a child of very low status, but these agonistic encounters may not take place. Our interest in the patterns of repeated interaction leads us to examine the interactions that do take place, and not simply the odds that hypothetical interactions would follow a certain pattern were they to take place. Accordingly, we reach a conclusion that is easily overlooked by the favoring of relations over relationships—status hierarchies need to spread people out so that there are sufficient spaces between each to reduce the sheer number of contests. This generally occurs in our data—over time, agonistic interactions zero in on the unresolved or reversible relations between those close in status and leave the larger differences as settled (compare Gould 2003).

Critiques of the concept of dominance have suggested that concern with dominance is more characteristic of men than women (e.g., Haraway 1991); other evidence does suggest that men are more likely to differentiate vertically (Fennell, Carchas, Cohen, McMahon, and Hildebrand 1978). This might be taken to imply that boys but not girls will show evidence of dominance orders. Indeed, McGrew (1972: 122) could not even test the hypothesis of a dominance order for nursery school girls as he could for boys because he did not observe enough agonistic encounters with a clearly defined outcome.

In support of such an assumption, Savin-Williams (1987: 125) concluded that “although the quantified data indicate that the female adolescent interactions could be construed on a group level as a dominance hierarchy,” there was no evidence of a linear hierarchy in three of the four female groups he studied. But results of fitting the Bradley-Terry model to the data do not confirm this. While we can quantify the degree of vertical hierarchy in any group with some conventional measure of fit such as the Cox pseudo-r-square (using this measure does not change our results), we can also measure the degree of verticality in terms of the spread of statuses. That is, the model retrieves latent (unobserved) statuses for all members—the further apart these are, the more vertical differentiation exists in the group (Martin 1998). I will use the standard deviation of these scores as a measure of this spread. Doing this, we find that of the half of the groups where the status hierarchy model fits best, half the groups are female and half are male.

Thus in contrast to popular impressions, it does not appear to be the case that American boys are more oriented towards chimplike dominance structures than are girls. Savin-Williams (1987: 109) himself found that because boys tended to contest dominance relations, the girls were in some cases more linear. Reanalysis using our parametric methods finds that while girls started out lower than boys in terms of the linearity of their dominance orders, they surpassed boys by the end of the summer (although this difference is not statistically significant).

This does not mean that girls do not differ from boys in their dominance behavior. Savin-Williams (1987: 105) found that boys tended to have more fights and verbal arguments, “but the most striking sex difference was in recognition of status behavior; giving compliments, asking favors, imitating, and soliciting advice occurred in every fourth encounter among female dyads, but only once in every sixteenth interaction among male dyads.” In other words, while boys might participate in more of the dominance activities that would attract the attention of a casual observers (only 48 percent of girls’ dominance related behavior was categorized as “overt,” as opposed to 85 percent of the boys’), girls more than made up for this with ritualized demonstrations of subordination. Boys may engage in more of the activities that are associated with “dominance” in the popular use of the term, but less of the ritualized submission activities that are structurally crucial. The greater aggressiveness of boys actually undermines the clarity of the dominance order.

Even more interestingly, it turns out that boys’ rankings seem to be constructed around the top ranking boy (the alpha boy), while girls’ seem to be constructed around the bottom ranking girl (the omega girl). Just as Savin-Williams (1987: 109, 121) found, among boys, alphas keep their position over time, while among girls, omegas keep their position. It might be that boys are oriented to popularity, and girls to unpopularity.40

Further insight here can be gathered by close examination of the residuals from the Bradley-Terry model. That is, given that we position people on a continuum of status via this model, the residuals point to relationships that stand out. (Here we can use the traditional rule of thumb of examining standardized residuals greater than 2 or less than –2.) The results are quite surprising, and they give clear evidence of two types of departures from a simple status order, which I shall call “sender” and “receiver” effects. In a “sender” effect, one child tends to under- (or over-) dominate others compared with what is expected by the model. In three of the four girl groups, the omega girl was such an underdominator.41 It is important to realize that this underdomina-tion is net of her position at the bottom of the hierarchy. To illustrate, we could imagine that most girls initiated 12 acts of dominance against those one step below them in the hierarchy, and initiated 4 acts against those one step above them. But the omega girl, though receiving 12 acts from the girl above her, might return only one or none at all.42 In other words, either omega girls quickly lose their ability to dominate, or those with a reticence to dominate are quickly assigned the position of omega (Martin 2009).