chapter 20

THE TRIAL OF BONNET’S CREW

As the trial began, the king’s commission to Judge Trott was read, and a grand jury was sworn.

Trott was joined by a slew of assistant judges, including George Logan, esquire, Alexander Parris, esquire; Philip Dawes, esquire; George Chicken, esquire; Benjamin De La Conseillere, esquire; Samuel Dean, esquire; Edward Brailsford, a gentleman; John Croft, a gentleman; Captain Arthur Loan and Captain John Watkinson.

Then the grand jury was called, and twenty-three men were sworn in, including

Michael Brewton, the jury foreman, |

John Breton, |

Robert Tradd, |

John Bee, |

Andrew Allen, |

Daniel Gale, |

Peter Manigault, |

Thomas Loyde, |

John Beauchamp, |

Laurence Dennis, |

John Bullock, |

Elias Foisin, |

Thomas Barton, |

John Shephed, |

Anthony Matthews, |

John Simmons, |

Alexander Kinlock, |

George Peterson, |

Henry Perrineau, |

Solomon Legare, |

Paul Douxsaint, |

Abraham Lesuir, and, John Caywood. |

Once the grand jury was sworn, Judge Trott gave his charge:

Gentlemen, we are here assembled to hold this Court of Admiralty Sessions, and the duty of my office requires me to give in charge to you the things that you are to enquire of and to present.

In a former Admiralty charge, by way of preface or introduction to the particular crime of piracy, which will now be brought before you;

I then shewed you, first, that the sea was given by God for the use of men, and is subject to dominion and property, as well as the Land.

And then I particularly remarked to you, the sovereignty of the kings of England over the British Seas.

I then proceeded, secondly, to shew you that as commerce and navigation could not be managed without laws, so there have been always particular laws for the better ordering and regulating marine affairs. . . .

But I shall now proceed, in the third place, to shew you that there have been particular courts and Judges appointed, to whose jurisdiction maritime cases do belong; and that in matters both civil and criminal.

And then I shall in particular shew you the constitution and jurisdiction of this Court of Admiralty Sessions.

And shall mention the crimes cognizable therein; and shall particularly enlarge upon the crime of piracy, that will now be brought before you.

Time will not permit me to speak of the several sorts of magistrates, to whose jurisdiction maritime Affairs do belong, in the transmarine or foreign parts of the World.

Therefore I shall confine myself, under this head only to speak of the laws of England, by which the general jurisdiction in marine affairs is by the King, as Supreme, as well by sea as land, committed to the Lord High Admiral, who besides his power over the navy, and the government over the seamen, hath jurisdiction civil and criminal matters in marine affairs, which are decided by his maritime judges in the Court of Admiralty, the chief of which is known by the style of Supremæ Curiæ Admiralitatis Angliæ Judex, within whose cognizance in the right of the jurisdiction of the Admiralty by the sea laws and the laws and customs of the Admiralty of England, are comprised all matters properly maritime and pertaining to navigation.

As to the antiquity of the Office of Lord Admiral, and the Court of the Admiralty, it is sufficient to remark, that the thing itself that signified that office, now known to us by the style of Lord High Admiral, and the jurisdiction thereof, hath been in the kingdom of England time out of mind. . . .

The Lord Coke in the first part of his Institutes, in honor of the admiralty of England, saith,

That the Jurisdiction of the Lord Admiral is very ancient, and long before the Reign of Edward III as some have supposed, as may appear by the Laws of Oleron, (so called, for that they were made by King Richard I, when he was there,) that there had been then an Admiral time out of mind, and by many other ancient Records in the Reigns of Henry III, Edward I, and Edward II is most manifest.

But the learned Selden in his Notes upon Fortescue, tells us, That in an ancient Manuscript “De l’Office de l’Admiralty,” translated into Latin by one Tho. Rowghton, calling it De Officio Admiralitatis, there are Constitutions often mentioned touching the Admiralty of Henry I, Richard I, King John, and Edward I, which shews the great antiquity of the Court.

And as to the jurisdiction of the Court of Admiralty, not to enter upon the disputes between the civilians and the common lawyers concerning the same, I shall now only observe to you, that it is allowed even by those statutes that were made purposely to restrain the jurisdiction of the Court of Admiralty, that that Court ought to have cognizance of all things done upon the main seas, or coasts of the sea. And of the death of a man, and of mayhem done in great ships, being and hovering in the main stream of great rivers, only beneath the bridge of the same Rivers nigh the sea.

And by the preamble to the statute of the 28 H. 8 it is declared, that Traitors, Pirates, Thieves, Robbers, Murderers, and Confederates upon the Sea, were tried before the Admiral or his Lieutenant or Commissary, after the Course of the Civil Law.

But, as appears further by the said preamble, that it was found inconvenient to try those offenders before the Admiral:

Therefore by the said Statute this Court of Admiralty Sessions was appointed, whereby such offenders were to be tried according to the course of the common law, as if their offences were committed on land.

And now I shall proceed to speak of the crimes cognizable in this court. And particularly I shall enlarge upon the crime of piracy that will come before you.

The crimes cognizable in this Court, and within the Jurisdiction of the same, by the express Words of the Statute, are all Treasons, Felonies, Robberies, Murders, and Confederacies, committed in or upon the Sea, or in any other Haven, River, Creek, or Place where the Admiral or Admirals have or pretend to have Power, Authority, or Jurisdiction.

There being only one of those crimes, viz. robbery or piracy, that will come before you, I shall omit the rest, and only speak to that: wherein I shall shew you the nature of the offence and the heinousness thereof.

Now, as this is an offence that is destructive of all trade and commerce between nation and nation, so it is the interest of all sovereign princes to punish and suppress the same.

And the King of England hath not only an Empire and Sovereignty over the British sea, but also an undoubted jurisdiction and power, in concurrency with other Princes and States, for the punishment of all piracies and robberies at Sea, in the most remote parts of the world.

Now as to the nature of the offence: Piracy is a robbery committed upon the sea, and a pirate is a sea thief.

Indeed, the word “Pirata,” as it is derived from “πεῖρᾰv, transire, a transeundo mare,” was anciently taken in a good and honorable sense, and signified a Maritime Knight, and an Admiral or Commander at sea, as appears by the several testimonies and records cited to that purpose by that learned antiquary Sir Henry Spleman in his Glossarium.

And out of him the same sense of the word is remarked by Dr. Cowel, in his Interpreter, and by Blount in his Law Dictionary.

But afterwards the word was taken in an ill sense, and signified a sea-rover or robber, either from the Greek word “πεῖga, Deceptio, Dolus, Deceipt,” or from the word “πεῖgar, transire,” of their wandering up and down, and resting in no place, but coasting hither and thither to do mischief. And from this sense . . . sea malefactors were called . . . “pirates.”

Therefore, a pirate is thus defined by Lord Coke, “This Word Pirate,” saith he, “in Latin Pirata, is derived from the Greek Word [meaning] . . . roving upon the sea: and therefore in English a Pirate is called a Rover and Robber upon the sea.”

Thus, the nature of the offence is sufficiently set forth in the definition of it.

As to the heinousness or wickedness of the offence, it needs no aggravation, it being evident to the reason of all men. Therefore a pirate is called Hostis Humani Generis, with whom neither faith nor oath is to be kept. And in our law they are termed brutes and beasts of prey, and that it is lawful for any one that takes them, if they cannot with safety to themselves bring them under some government to be tried, to put them to death.

And by the civil law any one may take from them their ships or vessels: so that excellent civilian Dr. Zouch, in his book De Jure Nautico, saith “In detestation of piracy, besides other punishments, it is enacted that it may be lawful for any one to take their ships.”

And yet by the same civil laws, goods taken by piracy gain not any property against the owners. Thus, in the Roman Digests or Pandects of Justinian, it is said, “Persons taken by Pirates or Thieves, are nevertheless to be esteemed as free.”

And then it follows, “He that is taken by Thieves, is not therefore a Servant of the Thieves, neither is Postliminy necessary for him.”

And the learned Grotius, in his Book De Jure Bell ac Pacis, saith, “Those things which Pirates and Thieves have taken from us, have no need of Postliminy, because the Law of Nations never granted to them a Power to change the Right of Property: therefore things taken by them, wheresoever they are found, may be claimed.

And agreeable to the civil law are the laws of England, which will not allow that a taking goods by Piracy doth divest the Owners of their Property, though sold at Land, unless sold in Market overt.

Before the Statute of the 25 E. 3, piracy was holden to be Petit Treason, and the offence said to be done contra Ligeanciæ suæ debitum, for which the offenders were to be drawn and hanged. But since that statute the offenders received judgment as felons. . . .

But still it remains a Felony by the Civil Law. And, therefore, though the aforesaid statute . . . gives a trial by the course of the Common Law, yet it alters not the nature of the offence. And the indictment must mention the same to be done super altum mare, upon the high sea, and must have both the words “Felonicè” and “Piraticè,” and therefore a pardon of all felonies doth not extend to this offence, but the same ought to be specially named.

Thus having explained to you the nature of the offence, and the wickedness thereof, as being destructive of trade and commerce; I suppose I need not use any arguments to you, to persuade you to a faithful discharge of your duty, in the bringing such offenders to punishment.

And indeed, the inhabitants of this province have of late, to their cost and damages, felt the evil of piracy, and the mischiefs and insults done by pirates. When lately an infamous pirate had so much assurance as to lie at our bar, in sight of our town, and seize and rifle several of our ships bound inward and outward.

And then had the confidence to send in his insolent demands for what he wanted, with threats of murdering our people he had on board him, if they were not complied with. Which was putting the province under contribution.

And the success he had in going from our coast with impunity, encouraged another of those beasts of prey to come upon our coast and take our vessels.

And this very company, which will now be charged before you with the crime of piracy, their ringleader, with many, if not all of the company, were belonging to that Crew which first insulted us. And presuming upon their former success and impunity, had the confidence to lie upon our coast to fit their vessel, and to go on shore at their will and pleasure, designing, as we had just reason to suppose, that when all things were fitted for their mischievous designs, to come again to cruise before our bar, and take our vessels.

And therefore upon the receiving these accounts, it was high time for the government to fit out a force against the pirates; and to endeavor to suppress them, in order to support our trade and commerce, which otherwise must have been inevitably ruined.

And being under such a necessity of having forces raised for that purpose, we cannot sufficiently commend and honor the zeal and bravery of those persons, who so willingly and readily undertook that expedition against the pirates, and so gallantly acted their parts when they engaged them.

But it will not be fit for me to say any more upon that subject, by reason of the near relation I stand in to the Commander-in-Chief of that Expedition, and who is known to you all to have so well acted his part therein, that as it is not proper, so he needs not my commendations.

But then I must not omit mentioning to you, that in this attack made upon those enemies of mankind, many of our People lost their lives in the discharge of their duty to their King and country, and who fell by the hands of those inhuman and murdering criminals which will now be brought before you. And the blood of those murdered persons will cry for vengeance and justice against these offenders.

And therefore I hope the consideration of doing justice to those persons who were killed in the service of their country, will make you to use your diligence in bringing the criminals to punishment, without which the blood of those persons will in a great measure be required at our hands.

I need not expatiate to you upon the heinousness of the sin of murder, a crime which carries its own natural horror and guilt along with it; so that it is altogether needless for me to aggravate it, and the manifest injustice and evil of which is evident to all persons, even by the light of nature: So that there is no nation so barbarous, but by their universal practice do consent to the equity and justice of that ancient Law of God, that “Whoso sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed,” Genesis 9:6.

Indeed, I freely grant, that the greatness of the crimes the persons are charged with, should make you the more careful in your enquiry, and to avoid any error or mistake on both extremes; that as you would not condemn the innocent, so likewise that you do not acquit the guilty, always remembering what the wise man saith, that “He that justifieth the wicked, as well as he that condemneth the just, even both are an abomination to the LORD,” Proverbs 17:15.

I have only this to add, that you being a Grand Jury, your business is not to try the prisoners, but to consider whether or no, by the evidence, there is that probable proof of the persons being guilty of the fact charged upon them, as that they ought to be put upon their trial for the same.

An indictment found by you being virtually but a legal accusation, there being another jury to pass upon them.

But on the other side, though your finding the Bill of Indictment is not conclusive to the prisoners, but that they will have a trial, and be heard in their own defence before another jury, which properly are said to try the Prisoners, and pass between the King and them upon their lives or deaths.; nevertheless, you ought to be cautious and diligent in your enquiry, and not rashly and carelessly find a Bill of Indictment against persons, and put them upon the hazard of a trial for a capital crime.

But as to those indictments that will now be brought before you, I am very will assured the proofs will be so clear and full, that you’ll have no reason to doubt the truth of the facts charged therein: and then I shall not question your faithful discharge of that great duty and trust the law hath reposed in you, in bringing such criminals to justice.

Thus having sufficiently explained to you what is likely to come before you, I shall now dismiss you to your business.

The prosecution, led by Thomas Hepworth and Richard Allein, the attorney general, depended on two indictments (discussed in more detail in the following chapters), and focused on the taking of the Francis, captained by Peter Manwareing, and the Fortune, captained by Thomas Read.

In the early 1700s, Hepworth was one of six practicing attorneys in proprietary South Carolina.186 Before serving as a prosecutor, Hepworth had served as the clerk of court. Hepworth would later serve as chief justice for South Carolina before being deposed in 1724. Hepworth’s home is still standing, and is the oldest home in Beaufort.

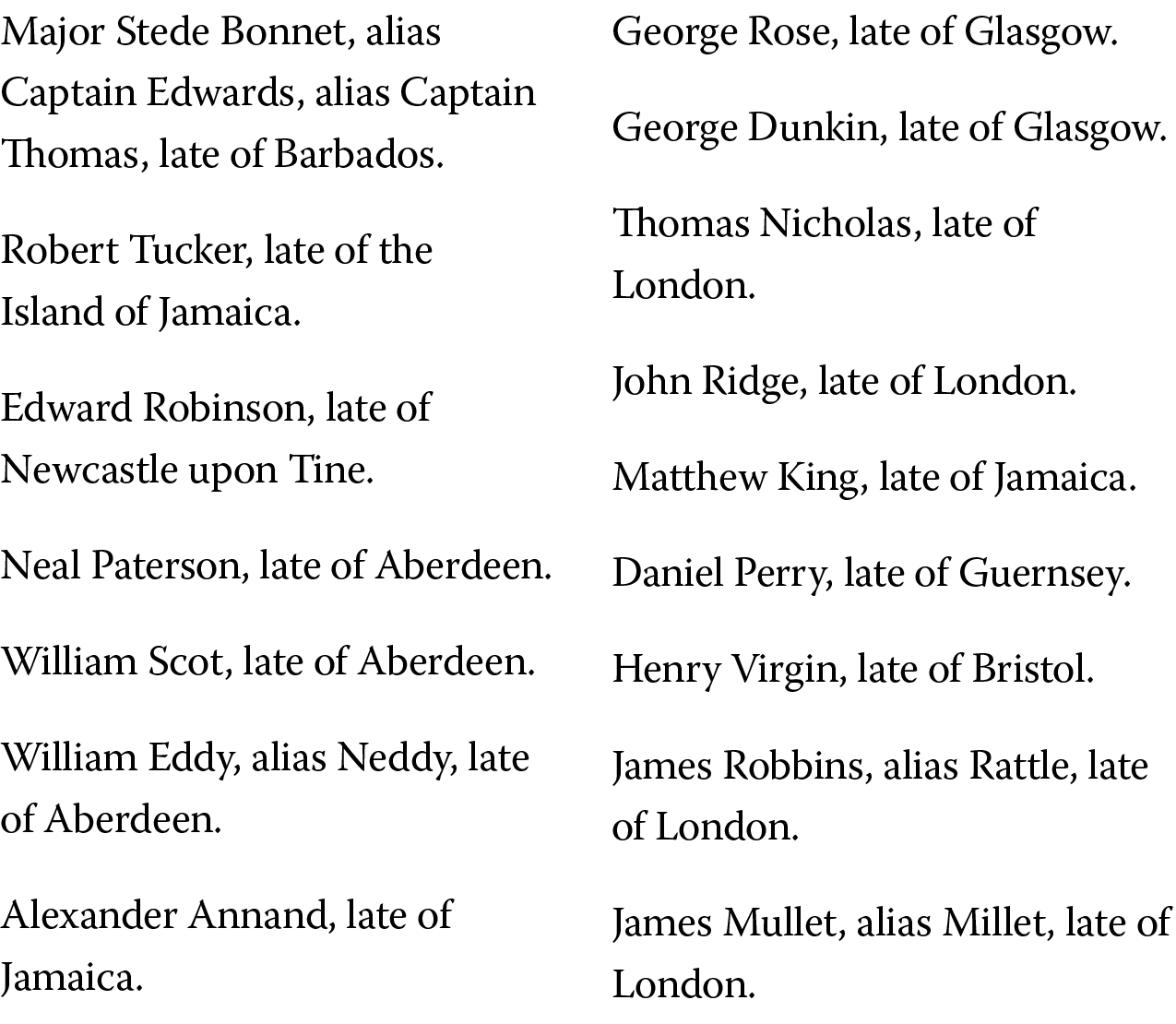

Under these indictments, Major Bonnet and his captured crew were arraigned and scheduled for trial, including

Major Bonnet was scheduled to be tried separate from the rest of his crew.

All of the prisoners pleaded not guilty, except James Wilson and John Levit, who pleaded guilty to both indictments, and Daniel Perry, to one only. None of the pirates were represented by counsel at trial (the law of England at the time did not allow counsel except in trials for treason).187

Clerk. Upon this indictment, they have been arraigned. Upon their arraignment, they have pleaded Not Guilty, and for their trial have put themselves upon God and their Country, which Country you are. Your charge is to enquire whether they, or any of them, are guilty of the felony and piracy of which they stand indicted, in manner and form as they stand indicted, or not guilty.

If you find them, or any of them, guilty, you shall then enquire what goods or chattels, lands or tenements, they, or any of them, had at the time of the felony and piracy committed, or any time since. But if you find them not guilty, etc. And hear your evidence.

Richard Allein, Attorney General. May it please your honors, and you gentlemen of the jury; the nature of the crime, piracy, for which the prisoners at the bar are now to be tried, and the Statute of the 28th of Henry the Eighth, entitled, ‘For Pirates,’ has been fully and learnedly laid open and explained by the Judge in his charge to the Grand Jury, (at which I am sensible most, if not all of you, were present).

Therefore, I shall say but little more on that head, and only remark that it is a crime so odious and horrid in all its circumstances, that those who have treated on that subject have been at a loss for words and terms to stamp a sufficient ignominy upon it, some calling them ‘Sea-Wolfs,’ others ‘Beasts of Prey,’ and ‘Enemies of Mankind,’ with whom neither faith nor treaty is to be kept. And all this is but a faint description of these miscreants:

For beasts of prey, though fierce and cruel in their natures, yet, as has been observed of them, they only do it to satisfy their hunger, and are never found to prey upon creatures of the same species with themselves. Add hereto, that those wild beasts have neither rational souls, understanding, nor reason to guide their actions, or to distinguish between good or evil.

But pirates prey upon all mankind, their own species and fellow creatures, without distinction of nations or religions; English, French, Spaniards, and Portuguese, and Moors and Turks, are all alike to them: For pirates are not content with taking from the merchants what things they stand in need of, but throw their goods overboard, burn their ships, and sometimes bereave them of their lives for pastime and diversion, as we have had frequent instances of late, and prove destructive to all trade and commerce in general. If a stop be not put to those depredations, and our trade no better protected, not only Carolina, but all the English plantations in America, will be totally ruined in a very short time.

The pirates are become very numerous and formidable in these Parts. The trade of America is no small advantage to the crown of Great Britain. Jamaica, by relation, is ruined by those pirates already. And other parts of America have suffered most grievously, and are like to share in the same fate. I know not what is done at home, therefore I cannot say no care at all has been taken of us. But this I do say, no effectual care has been taken to suppress those pirates. And if a true representation of these matters were laid before his Majesty, we could not but hope for some redress.

It is not my business to call in question the conduct of the Spaniards, in breaking up the Bay of Campeche. They could not but think the turning away such a number of profligate wretches, as were got together, must put them on a worse course of life. They have done them more harm since than cutting their log wood: for nine parts in ten of them turned pirates, and have lived upon robbing and plundering them and us ever since that time. That and the great expectations which so many had, from the Bahama Wrecks, were not one in ten proved successful, gave birth and increase to all the pirates in those parts, English, French, and Spaniards.

I just now instanced Jamaica as a place that is almost ruined by the pirates. But what occasion have we to look abroad? What a grievous dilemma were we ourselves reduced to in the month of May last? When Thatch, the pirate, came and lay off this harbor with a ship of forty guns mounted, and one hundred and forty men, and as well fitted with warlike stores of all sorts as any fifth-rate ship in the Navy, with three or four pirate sloops under his Command.

After having taken Mr. Samuel Wragg, one of the Council of this province, bound out from this place to London, as also one Mr. Marks, and several other vessels going out and coming into this harbor, they plundered those Vessels going home to England from hence of about fifteen hundred pounds sterling in gold and pieces of eight. And after that, they had the most unheard of impudence to send up one Richards, and two or three more of the pirates, with the said Mr. Marks, with a message to the government, to demand a chest of medicines of the value of three or four hundred pounds and to send them back with the medicines, without offering any violence to them, or otherwise they would send in the heads of Mr. Wragg and all those prisoners they had on board.

And Richards, and two or three more of the pirates, walked upon the bay, and in our public Streets, to and fro in the face of all the people, waiting for the governor’s answer. And the government, for the preservation of the lives of the gentlemen they had taken, were forced to yield to their demands. And some of those very prisoners now at the bar were part of that Thatch’s and Bonnet’s crew.

Afterwards, one Vaughan, another noted pirate, came and lay off our bar, and sent in another insolent message. This roused our spirits, and though reduced to a very low ebb by reason of the calamities of the Indian War, and long and heavy taxes, we could not bear those insults, but send out a force to suppress them.

However, we must own that that honorable gentleman, Colonel William Rhett, was the chief, if not the first promoter of fitting out two sloops to take some of those pirates. The government readily fell in with the measures proposed. Colonel Rhett went in person, accompanied by many gentlemen of the town, animated with the same principle of zeal and honor for our public safety and the preservation of our trade.

It is probable Vaughan the pirate, before things could be got in readiness, might have some intimation of our design, and made his way off the coasts, though all possible care was taken to prevent it.

However, Colonel William Rhett and the rest of the gentlemen were resolved not to return without doing some service to their Country, and therefore went in quest of a pirate they had heard lay at Cape Fear.

About the latter end of September they came up with and engaged them. The Fight lasted above six hours, and the pirates were forced to surrender, though the Colonel’s Vessel running a ground, lay under all the disadvantages in the world, as you are all sensible.

The piratical crew at the bar, and now to be tried, in the engagement, killed ten or eleven of our men on the spot, and wounded about eighteen, several of which died since they came on shore here.

This pirate sloop was commanded by that noted pirate Major Stede Bonnet, and formerly called the Revenge, now the Royal James, and was one of those very Sloops that lay off the harbor of Charles Town about May last, when they took Mr. Wragg Prisoner, and sent up their insolent demands to the governor, as I have mentioned before.

We must all own, that the undertaking and design of fitting out those sloops after these pirates, was bold and noble, and carried on with prudence and courage, and crowned with victory and success. I hope Colonel Rhett, and the rest of the gentlemen that were with him, will meet with both thanks and rewards suitable to their great merit, and the credit and reputation they have brought to this province by this gallant action.

But see how justice follows those wicked offenders! They are now brought to suffer in that Country which they so lately insulted. It is true, Bonnet had not the sole command of his sloop when he lay off the bar, but was turned out some time before by Thatch, but that was not Bonnet’s fault.

Bonnet’s escape out of prison is no small misfortune to us. First, because some will be reproached with conniving at his escape that had no hand in it, and though they be never so innocent. . . .

I am sensible Bonnet has had some assistance in making his escape, and if we can discover the offenders, we shall not fail to bring them to exemplary punishment.

And now, gentlemen of the jury, I must remind you of your duty on this occasion. You are bound by your oaths, and are obliged to act according to the dictates of your consciences, to go according to the evidence that shall be produced against the prisoners, without favor or affection, pity or partiality to any of them, if they appear to be guilty of those crimes they are charged with. And you are not allowed a latitude of giving in your verdict according to will and humor.

I am sorry to hear some expressions drop from private persons, (I hope there is none of them upon the jury) in favor of the pirates, and particularly of Bonnet: that he is a gentleman, a man of honor, a man of fortune, and one that has had a liberal education. Alas, gentlemen, all these qualifications are but several aggravations of his crimes.

How can a man be said to be a man of honor, that has lost all sense of honor and humanity, that is become an enemy of mankind, and given himself up to plunder and destroy his fellow creatures; a common robber, and a pirate?

Nay, he was the archipirata, as it is now taken in the worst sense, or the chief pirate, and one of the first of those that began to commit those depredations upon the seas since the last peace.

I have an account in my hand of above twenty-eight vessels taken by him, in company with Thatch, in the West Indies, since the 5th Day of April last, and how many before, nobody can tell.

His estate is still a greater aggravation of his offence, because he was under no temptation of taking up that wicked course of life.

His learning and education is still a far greater aggravation; because that generally softens men’s manners, and keeps them from becoming savage and brutish. But when these qualifications are perverted to wicked purposes, and contrary to those ends for which God bestows them upon mankind, they become the worst of men, as we see the present instance, and more dangerous to the Commonwealth. . . .

We shall call the Evidence, and prove the facts fully and clearly upon them. Take notice, gentlemen, that the boarding, breaking, and entry of one, if the rest were present and consenting, is the boarding, breaking, and entry of all the rest.

Thomas Hepworth. May it please your Honors, and you gentlemen of the jury, the crime the prisoners now stand charge with, is piracy, which is the worst form of robbery, both in its nature and its effects, since it disturbs the commerce and friendship betwixt different nations, and if left unpunished, involves them in war and blood. What calamities and ruin they carry along with them, no person can be a stranger to; so that those that bring not such criminals to judgment, when it lies in their power, and is their duty to do so, are answerable in a great measure, before God and man, for all the fatal consequences of such acquittals, which bring a scandal on the public justice, and are often attended with public calamities.

It is not therefore, gentlemen, to be supposed that wise or honest men (and there is none who would willingly be thought otherwise), who love their Country, and wish its peace and prosperity, would be guilty in that kind.

What has been said by the King’s Attorney, or myself, upon this unexpected occasion, I hope will not be looked upon as intended to influence any of the jury. I am sure it is far from being so designed. Religion, conscience, honor, common honesty, humanity, and all laws forbid such methods. There is no doubt but the judges as well as the jurymen best discharge their duty when they proceed without favor or affection, hatred or ill-will, or any partial respect whatsoever. Malice and favor (two great enemies to justice) are to be excluded all courts of judicature as too partial.

Every man ought to be extremely tender of such a person as he has reason to believe is innocent. But it should be considered likewise, on the other side, that he who brings a notorious pirate or common malefactor to justice, contributes to the safety and preservation of the lives of many, both bad and good. Of the good, by means of the assurance of protection, and of the bad too, by the terror of justice. It was upon this consideration that the Roman emperors, in their edicts, made this piece of service for the public good as meritorious as any act of piety or religious worship.

Our own laws demonstrate how much our legislators, and particularly how highly that great Prince King Henry V and his Parliament, thought England concerned in providing for the security of traders, and scouring the seas of rovers and freebooters. Certainly, there never was any age wherein our ancestors were not extraordinary zealous in that affair. Looking upon it, as it is and ever will be, the chief support of navigation trade, wealth, strength, reputation and glory of the English Nation.

Gentlemen, our concern, as our trade is, ought in reason to be rather greater than that of our forefathers. We want no manner of inducements, no motives to stir us up, whether we consider our interest or honor. We have not only the sacred word, but also the glorious acts of the best of kings, which sufficiently manifest to us, that the good and safety of the English Nation is the greatest care of his life.

Let every man, therefore, who pretends to anything of a true English spirit, readily and cheerfully follow so good, so great, so excellent an example, by assisting and contributing to the utmost of his power and capacity at all times towards the carrying on his noble and generous designs for the common good; and particularly at this time, by doing all he can, to the end that by the administration of equal justice, the discipline of the seas, on which the good and safety of the English nation, and these parts of America more especially, entirely depends, may be supported and maintained.

The civil law terms the pirates ‘Beasts of Prey,’ with whom no communication ought to be kept. Neither are oaths or promises made to them binding. And by the Law Marine the captors may execute such beasts of prey immediately, without any solemnity of condemnation, they not deserving any benefit of the law.

I believe, gentlemen, that no greater motives can be urged to spur you on in your duty, than to desire you to reflect and consider how long our Coasts have been infested with pirates (for the name of Men they do not deserve), and how many vessels they have taken and pillaged belonging to this place, as well as multitudes of others belonging to divers parts of his majesty’s dominions, and how many poor men in whose blood they have imbrued their hands with the greatest inhumanity imaginable, and how many poor widows and orphans they have made, and how many families they have ruined and how long they have gone on in their abominable wickedness.

Nay, do but consider how those very pirates lately insulted this Government, when they sent for Medicines, threatening to destroy our vessels and men in case of refusal. Nay, since these have accepted of Certificates from the Government of North Carolina, like a dog to their vomits they have returned to their old detestable way of living, and since taken off these coasts thirteen vessels belonging to British subjects.

I believe you can’t forget how long this town has labored under the fatigue of watching them, and what disturbances were lately made with a design to release them, and what arts and practices have been lately made use of and effected for the escape of Bonnet their Ringleader; the consideration of which shows how necessary it is that the law be speedily executed on them to the terror of others, and for the security of our own lives, which we were apparently in danger of losing in the late disturbance, when under a notion of the honor of Carolina, they threatened to set the town on fire about our ears.

Even with their “not guilty” pleas, the prisoners made little or no defense, and much of the defense followed the same general pattern: that the pirates had been marooned on an island by Blackbeard, were picked up by Major Bonnet with the expectation of going to St. Thomas for the purpose of privateering, but once they were out to sea, they ran out of provisions and were forced to take up pirating.

The facts and testimony showed, however, that the crew was made up of active participants who had all shared ten or eleven pounds per man. It was the desire for money, not physical coercion, that elicited their participation.

In all, twenty-nine of Bonnet’s crew were found guilty, including Robert Tucker, Edward Robinson, Neal Paterson, William Scot, Job Bayley, John-William Smith, John Thomas, William Morrison, Samuel Booth, William Hewet, William Eddy, Alexander Annand, George Ross, George Dunkin, Matthew King, Daniel Perry, Henry Virgin, James Robbins, James Mullet, Thomas Price, John Lopez, James Wilson, John Levit, Daniel Perry, and Zachariah Long, and sentenced to death by hanging. Four were acquitted.

186 St. Philip’s Church of Charleston: An Early History of the Oldest Parish in South Carolina, Dorothy Middleton Anderson & Margaret Middleton Rivers Eastman (2014).

187 History of South Carolina, 179 (Volume I, 1920).