1 Introduction: We Are What We Preserve—and Don’t Preserve

A Monument is a thing erected, made, or written, for a memoriall of some remarkable action, fit to bee transferred to future posterities. And thus generally taken, all religious Foundations, all sumptuous and magnificent Structures, Cities, Townes, Towers, Castles, Pillars, Pyramids, Crosses, Obeliskes, Amphitheaters, Statues, and the like, as well as Tombes and Sepulchres, are called Monuments. Now above all remembrances (by which men have endevoured, even in despight of death to give unto their Fames eternitie) for worthinesse and continuance, bookes, or writings, have ever had the preheminence.

—John Weever, Ancient Funerall Monuments within the United Monarchie of Great Britain (1631)1

The preservation of cultural heritage is a monumental task. The aim of this book is to explore the preservation of movable, immovable, human-made, and socially constructed heritage in an expansive way. Studies in preservation have tended to reflect particular disciplinary lines: library and archival studies, museum studies, art history, historic preservation, and other fields that focus on preservation from particular vantage points. The premise of this book is that there are broad preservation issues that can be viewed through a variety of disciplines. Law, political science, business, architecture, computer science, geography, cultural tourism and cultural heritage management, sociology, and environmental science (itself a multidisciplinary academic field) are some of the fields that address preservation-related issues. For example, international laws may be essential to recovering stolen artifacts or protecting heritage in war. Natural disasters affect heritage collections; disaster preparedness and recovery can be approached from many angles including public policy, science, and the sociology of disasters. Anthropology and history offer approaches to understanding and addressing multicultural issues in preservation. This book considers many ways of looking at preservation.

In the heritage fields, preservation, conservation, and restoration are sometimes used interchangeably—and sometimes have distinct meanings. Preservation is used most often to refer to the general care of collections and the built environment. It refers to environmental monitoring, security, conservation, sustainability, and guardianship or stewardship of objects and collections. With respect to the built environment, preservation activities may include stabilization, restoration, rehabilitation, or reconstruction. Conservation usually refers to the treatment and care of objects. The aim of restoration is to return something damaged or flawed to an earlier known—or imagined—condition. For Ellen Pearlstein,

[conservators] are those whose activities are devoted to the preservation of cultural heritage.… Since conservation is also a term applied to the protection of biodiversity, cultural heritage specialists often distinguish their field by applying the limiting phrase “art conservation,” perhaps more accurately termed cultural conservation as the field encompasses a broad range of specialties including natural history specimens, archives, and books.… Restoration has a narrower focus than conservation and one that is tied to presentation value. The complete emphasis on restoration without regard for preservation or accurate interpretation has been emphatically rejected in the modern definition of conservation.2

In the 1970s, William Lipe proposed a preventative conservation model for American archeology in response to the then “growing rate at which sites are being destroyed by man’s activities—construction, vandalism, and looting of antiquities for the market.”3 This approach included public education, the involvement of archeologists in land use planning, the establishment of archeological preserves, and so on. His work paralleled the efforts of conservators such as Paul Banks (in libraries and archives) and Caroline and Sheldon Keck (in museums), as well as others whose conservation work fostered collaboration, education, and outreach. Now, a generation later, there are new opportunities for collaboration and outreach.

While “conservation usually refers to the treatment of objects that is based on scientific principles and professional practices, as well as other activities that assure collections care and mitigate damage,”4 its reach continues to expand. Salvador Muñoz Viñas points out that conservation can also be used in a broad sense to refer to “diffuse boundaries, since it may involve many different fields with a direct impact on the conservation object.… [N]on-conservators’ conservation deals with other technicalities within many varied fields (law, tourism, politics, budget-allocation, social research, plumbing, vigilance systems, masonry, etc.).”5 Muñoz Viñas includes in his book a figure that depicts conservation emerging from a box in which many other fields overlap it.6

In the present text preservation will be used except in specific instances in which other terms are more precise. My aim here is to concentrate on preservation, with some of the nuances of meaning that the other two terms conservation and restoration suggest. Preservation continues to evolve. New forces such as social networking are beginning to have a profound influence on the heritage fields. Crowdsourcing is but one example of how the public already is becoming engaged in preservation projects.

While the focus of this book is on preservation, consideration of destruction is a necessary component of that focus. Natural and manmade destruction threatens the preservation of cultural heritage. Natural disasters, ideology (e.g., “cultural cleansing” and cultural genocide), fanaticism, biblioclasm, and military action may lead to the destruction of objects and sites. Administrative decisionmaking for analog and digital collections is yet another cause of destruction; collections may be weeded, records may not be retained, or collections may deteriorate due to neglect. Benign neglect and inaction fall between preservation and destruction. Such inaction may stem from cultural beliefs, the inability to care for collections, forgetfulness, denial of global warming, or any other cause that leads to deterioration or loss.

Figure 1.1 illustrates traditional motivations for preservation as well as behaviors that may have stemmed from historic practices. At the same time, there are emerging trends. Social networking has influenced how we create, disseminate, and share information. Personal information management and personal digital archiving are relatively new disciplines that study how people organize their information. Understanding such information organization practices could lead to the creation of new digital preservation services and products. Community archiving is another movement that is on the rise. Communities may develop new approaches to preserving their records, which may or may not be similar to practices in heritage institutions.

Aspects of preservation. Image by Vanessa Reyes and Michèle V. Cloonan

There are four components to the schema shown in figure 1.1: (1) “Motivations,” and (2) “Behaviors,” which may be based on (3) “Historic Practices,” and (4) “Emerging Trends.” The areas overlap. Motivations, historical practices, and behaviors may persist at the same time that emerging trends offer new approaches and attitudes toward preservation. For example, while we may continue to preserve our heritage, it may become increasingly difficult to do so as digital art and information are usually diffuse and ephemeral. At the same time, new technologies may offer ways to “preserve” the old. One such technology, IRENE (Image, Reconstruct, Erase Noise, Etc.), was developed by physicist Carl Haber.7 (He so named his machine because the first recording that he preserved was the song “Goodnight Irene” by the Weavers.) An old sound recording that is cracked, or otherwise damaged, can now be produced using a combination of optical imaging and high-resolution scanning. IRENE converts the data into patterns that are readable and playable.

The rapid growth of digital personal information—in part brought about through social networking—suggests that all people will have to manage and preserve their own information, or risk losing it. At the same time the preservation of historical sites, analog information, the physical landscape, and digital media is often dependent on legal and social contracts. Thus the social, legal, and political context in which objects reside will impact preservation.

The schema suggests the complex web—and monumental undertaking—of preservation. Thus the inclusion of monumental in the title of this book refers to monuments as objects, but it also suggests the monumental efforts of preserving the world’s heritage against war, climate change, terrorism, and natural disasters. There are other monumental issues addressed as well, such as community outreach, indigenous heritage rights, sustainability, and what preservation means in an era of increasingly ephemeral heritage. Are all texts that are born digital (emails, social media, blogs, tweets, and much more) worth preserving? If so, who will decide what to preserve? In what medium? For how long? And at whose expense?

This book is about preserving cultural heritage writ large, or monumental preservation—that is, the aspect of preservation that is broader than the day-to-day practices of conservation and preservation. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has several definitions of monument including (2) “a written document, record; a legal instrument; and (4) anything that by its survival commemorates a person, action, period, or event.”8 Of interest here is that the OED definition includes written documents. The idea that the written word can stand as a monument goes back at least two thousand years. Martial observed that “A fig-tree splits Messalla’s marble and a rash mule-driver laughs at Crispus’ defaced horses. But writings no theft can harm and the passing centuries profit them. These monuments alone cannot die.”9

Some fifteen hundred years later, Shakespeare echoed Martial’s sentiment when he wrote in Sonnet 55 that “Not marble nor the gilded monuments of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme.” For both writers, marble was used as the metaphor for so-called permanent monuments.

Similarly, the Latin monumentum refers to written memorials, annals, and memoirs.10 Monumental refers to monuments as well as tombs, and it implies a vastness or extensiveness that is far-reaching. Thus by using monumental, I am presenting a broad and impressively large and enduring scope of subjects that sometimes directly—and often indirectly—impact preservation. One aim of the book is to inspire the reader to see how these broad themes impact our professional practices—and our lives.

This book also explores the premise that we are what we preserve. That statement might seem obvious—a result of the “accidents” of history. In fact, every day we make preservation decisions, individually and collectively. Some decisions may have longer-term ramifications than were originally anticipated. (A collection is discarded, and needed later on. A new road is built near an ancient site, which increases tourism [and traffic], and leads to the deterioration of the site. We choose to delete emails or text messages—or to save them somewhere.)

Finally, a book on preservation must consider why we preserve at all. What are our motivations? What is our motivation discourse—or discourses, as different fields may have distinct reasons for preservation?11 Any consideration of preservation must be simultaneously broad and nuanced.

What Is a Monument?

In his early definition of monuments (quoted earlier), John Weever (1576–1632) expressed the importance of particular types of public buildings, churches, and memorial structures. Nearly four hundred years later, we have broadened his concept. Monuments may refer to structures that commemorate people, groups, or events. Sometimes structures not intended as monuments become them. For example, the Great Wall of China was erected as a fortification structure, but many see it as a monument to Chinese civilization. At the other end of the scale from the Great Wall, there are small monuments; for example, in California, there is one that was erected to honor the Chinese who built the California railroads (figure 1.2). (However, efforts are afoot to create larger monuments to the Chinese and to resurrect this neglected aspect of California history. For many, a monument must be monumental.)

Chinese Railroad Workers Memorial Monument, Gold Run, CA. Photo by Sidney E. Berger and Michèle V. Cloonan, February 12, 2017

Art historian Alois Riegl (1858–1905) wrote:

In its oldest and most original sense a monument is a work of man erected for the specific purpose of keeping particular human deeds or destinies (or a complex accumulation thereof) alive and present in the consciousness of future generations. It may be a monument either of art or of writing, depending on whether the event to be eternalized is conveyed to the viewer solely through the expressive means of the fine arts or with the aid of inscription; most often both genres are combined in equal measure.12

While the aim of Riegl’s essay is to examine “artistic and historical monuments,” his expansive definition of monuments is useful to the aim of this book, which is to show that preservation is a monumental undertaking. He also mentions the importance of inscription, echoing my earlier citation from the OED that says that words—written documents—constitute one form of monument.

Sigmund Freud further developed the idea that monuments may evoke “the consciousness of future generations” in his essay “A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis.”13 For Freud, a trip with his brother to the Acropolis in 1904 became a metaphor for his own life’s journey. He describes his “joyful astonishment at finding myself at that spot,” while simultaneously feeling guilt and disbelief that he had made it to Athens. Freud reflected on what he and his brother had accomplished as compared to their father, who had neither gone to university nor traveled very far. Freud experienced these epiphanies on the site that is a powerful symbol of Western civilization—and Greek culture and mythology. The essay was written in 1936 as a letter to Romain Rolland “on the occasion of Rolland’s seventieth birthday” and toward the end of Freud’s life. In the thirty-two years between Freud’s visit to the Acropolis and his letter to Rolland, this monumental experience still had a hold on his sensibilities.

Freud conveys the power of his visit this way: “When, finally, on the afternoon after our arrival, I stood on the Acropolis and cast my eyes around upon the landscape, a surprising thought suddenly entered my mind: ‘So all this really does exist, just as we learnt at school!’” At the end of the essay he corrects himself—he never “doubted the real existence of Athens. I only doubted whether I should ever see Athens.”14

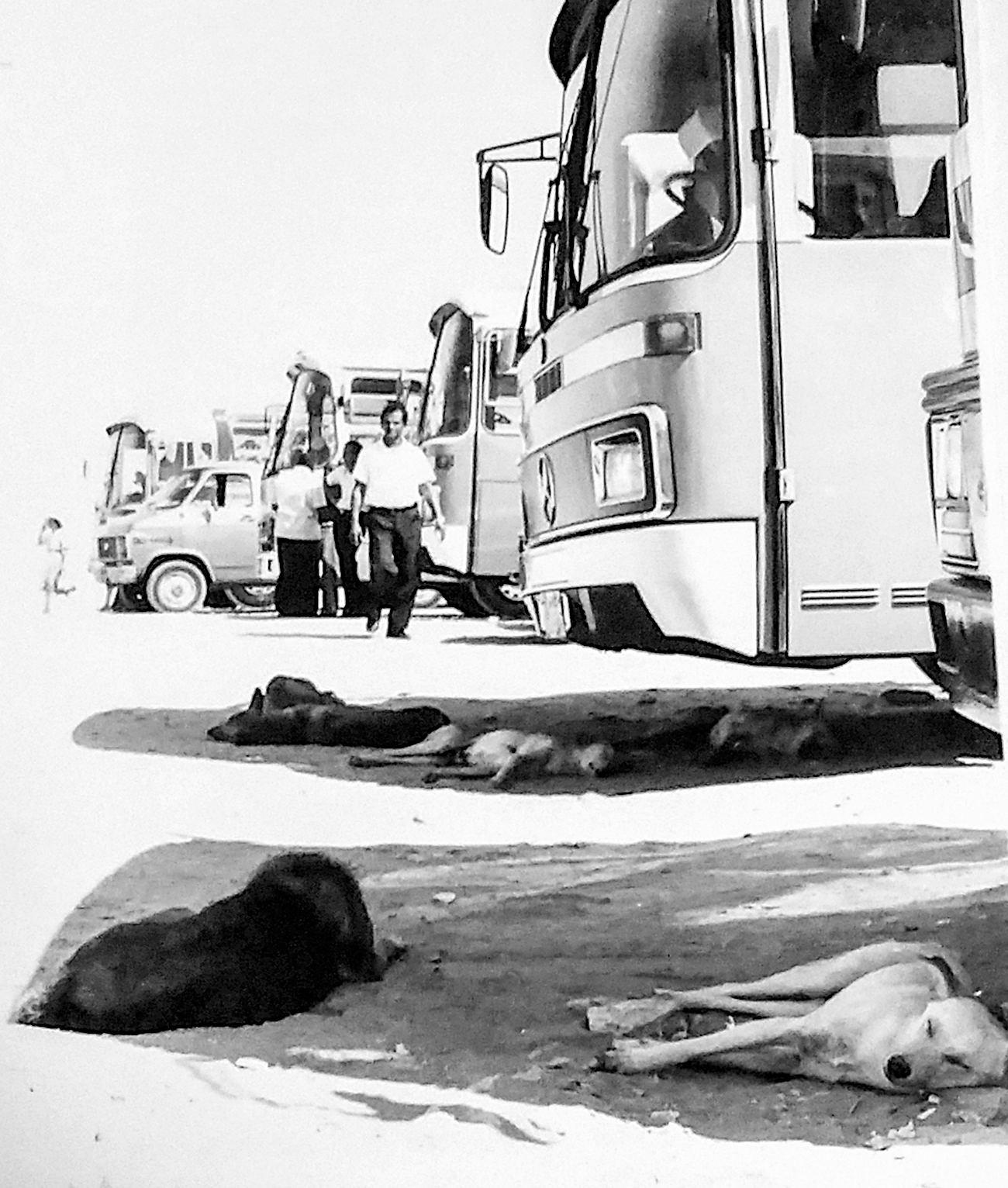

Freud’s multilayered interpretation of his experience at the Acropolis is suggestive of the experiences that many of us have when visiting famous landmarks. I remember the range of emotions I felt when I visited the Great Sphinx of Giza: first, excitement at seeing it, followed by disappointment that it seemed much smaller “in real life” than in the photos that I had seen of it. I felt frustrated that the site was surrounded by vendors aggressively trying to sell their souvenirs, uncomfortable in the extreme heat of that day, and cross that there was nothing to drink—only souvenirs for sale. At the same time I felt lucky to have been able to travel to Egypt, and guilty for feeling cross. Yet I was more taken by the dogs sleeping in the small amount of shade provided by the tourist buses—how they got there, how they would survive—than in the Sphinx that I had traveled so far to see (figures 1.3 and 1.4).

The Great Sphinx of Giza, Egypt. Photo by Michèle V. Cloonan, 1980

Tour buses and dogs near the Great Sphinx of Giza. Photo by Michèle V. Cloonan, 1980

The Sphinx was less monumental than I had anticipated; and all these years later I still remember vividly the responses I had then. So the experience—accompanied by my memory—had its own “monumental” impact on me. This is one of the messages of the present book: that monumental preservation can be an intensely personal phenomenon, at the same time that it is a social or historical phenomenon.

Our complex and evolving relationship with monuments—and how (or whether) to preserve them—is a recurrent theme of this book. For some people, all monuments are worthy of preservation. For others—as we shall see in my discussion of the Bamiyan Buddhas—some monuments must be destroyed. For Weever in particular, a monument implied “eternitie” while Riegl allowed for the more temporal “consciousness of the future.” How might we define eternity or future today? Our time horizons for the preservation of monuments are now much shorter, and the concept of monument continues to evolve. While this book does not focus on individual monuments, they appear throughout the book and different insights about them are presented.

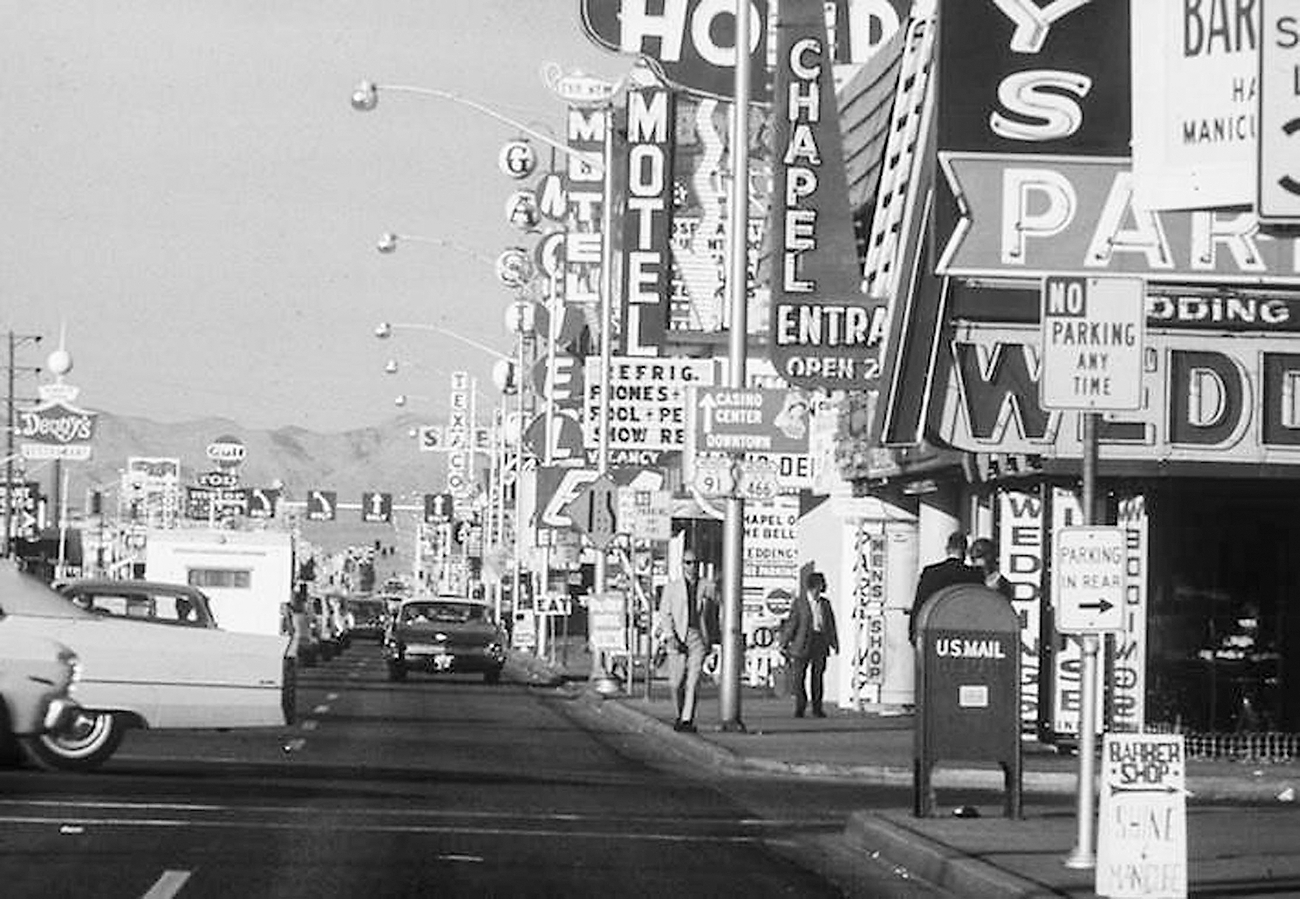

In Learning from Las Vegas, Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Steven Izenour debunk the idea that buildings needed to be “heroic.”15 They contend that “learning from the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary for an architect.”16 The architecture of the desert has a lot to teach us about the role of the natural landscape in the West. But most striking, perhaps, is the synthetic aspect of Las Vegas: commercialism, popular culture, superhighways, and the automobile that came to characterize this mid-twentieth-century type of urban environment, propelled, in part, by President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 that created a 41,000-mile national system of interstate highways. The photographs that Brown took of Las Vegas are stunning, exemplifying the theme of architecture and communication that runs through the book, and demonstrating a new type of monumental beauty—though not everyone would view Las Vegas that way. But perhaps it is not too much of a stretch to contend that there is something monumental about the architecture that is visible from so many miles away. And sometimes—depending on the weather conditions and the time of day—the buildings are almost mirage-like, as one approaches them on Interstate 15.

These photographs illustrate the monumentally garish and the monumentally beautiful aspects of Las Vegas (figures 1.5 and 1.6). The image of the Stardust Hotel against a magnificent sunset is a dreamscape, while the Strip is an assault to the senses. The city can have the same impact on people as more traditional monuments have: awe, wonder, and even, for many, horror. Monuments may engender a visceral or emotional response in those who encounter them, and not all responses will be positive.

Minor commercial buildings and signs on The Strip, 1965, by Denise Scott Brown. Permission of MIT Press

Stardust Hotel and Casino, 1965, by Denise Scott Brown. Permission of MIT Press

Another structure that led to a new way of thinking about monuments, and one exemplifying this emotional response, is Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial (dedicated in 1982)17 (figure 1.7). An open competition was held to select the design. Four criteria were included in the call for submissions: the design must include the names of everyone who was killed or missing, harmonize with the National Mall site, facilitate a healing process, and not make a political statement.18 Lin submitted her bold, modern design while she was an undergraduate student at Yale University. Instead of a monument consisting of idealized warriors, soldiers on horseback, or laurel wreaths, Lin designed a stark, simple wall onto which would be etched the names of the 58,272 Americans who had died or disappeared in Vietnam. This moving work of polished black granite is shaped like an elongated V—evoking Vietnam, veterans, victims.19 Part of the power of Lin’s creation—beyond the names—is the tactility of the monument, which allows people to touch the letters and not be distracted by anything pictorial.

Vietnam Wall with “offerings.” Permission of Kathy Brendel Morse, photographer

Figure 1.7 (continued)

The design was controversial, inspiring a change in the United States in the way that war memorials were conceptualized. Vietnam was not a “heroic” war and thus called for a new approach to memorialization. The monument gives voice to those who died in the war rather than presenting an idealized view of a solitary, abstract figure. Yet the initial reaction to Lin’s design was fierce, referred to as a “black gash of shame” among many other derogatory descriptions by veterans, politicians, and critics alike. Lin’s design unleashed the many complexities of the Vietnam War and Americans’ response to it. The emotional response I just spoke of, then, can be negative as well as positive.

To appease the many critics, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund added a traditional bronze statue in 1984 titled “Three Servicemen” by the sculptor Frederick Hart. This piece was criticized for being sentimental, for detracting from the Maya Lin design, and for ignoring the women who served in the military. This led to the addition of another bronze representational monument, Glenna Goodacre’s “Vietnam Women’s Memorial,” in 1993. Her statue depicts three nurses who are attending to a wounded male soldier. The nurse in the foreground and the soldier in this nouveau Pietà resemble the Virgin Mary and Christ.

The statues are positioned in awkward juxtaposition to “the Wall,” as Lin’s monument is often called. Some feel that the integrity of her design was compromised by the addition of the Hart and Goodacre statues. And yet their inclusion provides an ongoing dialogue about the meaning of monuments. Lin’s work is one of the most visited monuments in Washington, DC; in 2011, it was the second-most visited after the Lincoln Memorial.20

One important aspect of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has preservation implications: people began to leave personal objects in front of the memorial even before it was completed. In this respect, Lin created an early interactive experience with mourners that is similar to the instant memorials that are created alongside highways, at accident scenes, or at any locale where someone has met an untimely death. Tributes that have been left at the Wall are gathered by the National Park Service and stored in a climate-controlled facility in Latham, Maryland. To date, some four hundred thousand items are in the collection. A virtual exhibit, “Items Left at the Wall,” a collection of 500 objects, was released online on August 6, 2015.21 There are plans to add more items to it, which will turn this online resource into another monument.

Judith Dupré believes that

the rise of the spontaneous memorial—the practice of leaving mementos at locations where tragedy has occurred—is directly related to the ubiquity of photography and reaches back still further to the cartomaniacal blurring of the distinction between the individual and the celebrity.… Photography abets the spontaneous memorial itself by reproducing its image, which inspires yet another segment of the population to make a therapeutic deposit at the growing mountain of offerings.22

Today memorializing (a result of monument construction) also takes place online, through a variety of websites that make it possible to commemorate the deceased. These include 1000 Memories, GoneTooSoon, Remembered.com, and Memorial Matters. This is but one example of the role that social networking plays in preservation activities; others will be described in later chapters. It is probable that in time, even more memorializing will take place online. However, the creation of physical monuments will not abate soon. People still seek physical “places of memory.”

A visual debunking of the heroic monument is Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset’s “Powerless Structure, Fig. 101” seen here on the Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square in 2012–2013 (figure 1.8).23 The northwest plinth was originally intended to have on it an equestrian statue of William IV, but the funding never materialized. Since the late 1990s artists have been invited to create works for the plinth, which remain on display from a year to a year and a half. Many of the works playfully challenge the notion of the traditional monumental statue. Elmgreen and Dragset suggest in their statue that there is a heroism to childhood that is worthy of commemoration. But there are many possible readings of the work, including the obvious play on important men on horses. If monuments aim to elicit emotions, then humor and playfulness are not out of place, as the Elmgreen and Dragset statue shows. (Their powerful “Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under the National Socialist Regime” is discussed in this book’s “Epilogue: Berlin as a City of Reconciliation and Preservation.”)

“Powerless Structure,” by Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset. From Flickr Creative Commons

There are also nontraditional monuments such as the AIDS Memorial Quilt that was begun in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1987. It is monumental in ambition and size. By the end of 1987 there were 1,920 panels; today there are 98,000, with new panels being created all the time. (There are some “half a million articles in the Quilt Archives which include letters, cards, photos, books, clippings, artwork, etc. that we receive with the panels.”24) Dupré describes the AIDS Memorial Quilt as “an atypical monument. It is the quintessential anti-monument, not heroically ascendant, but laid low on the ground. It is soft, domestic, intimate yet epic. Made of acres of fabric … [it is] more vulnerable than stone or steel, it is a democratic monument.…”25 Because quilts can be made by anyone, and with salvaged scraps just as easily as with expensive fabrics, they are an egalitarian medium. The quilt (see figure 1.9) is maintained and exhibited by the NAMES Project Foundation.26

Panels from the AIDS Memorial Quilt, n.d. Permission of the NAMES Project Foundation

While the quilt may not have some of the characteristics of “fixed” monuments (e.g., composed of enduring materials like stone or metals), it has its own monumentality in its size and in the number of people who have contributed to it—and also the fact that it is not fixed in time and place, like a traditional monument, but is like a living entity that continues to grow. At the same time, it cannot be preserved in the traditional sense because its composition continues to change. Like performance art, it may only be possible to preserve versions of it with scanned or photographic images as it appeared in particular times and places.

* * *

What role does preservation play when objects are at the point of destruction, or have been destroyed? Architectural historian Richard Nickel’s comprehensive documentation of buildings slated for—or in some cases undergoing—demolition is the subject of chapter 6, “Worth Dying For? Richard Nickel and Historic Preservation in Chicago.” Nickel died in 1972 when architectural gems were being demolished at an astonishing rate in large American cities, often in the name of urban “renewal.” His efforts to preserve the buildings of Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan were seldom successful, though he was able to salvage pieces of some of their buildings. And his careful research on and photo-documentation of Sullivan’s work after the Sullivan/Adler partnership dissolved have provided invaluable resources to scholars. A magnum opus on Adler & Sullivan, which Nickel started but never finished, was completed by Aaron Siskind, John Vinci, and Ward Miller and published in 2010.27

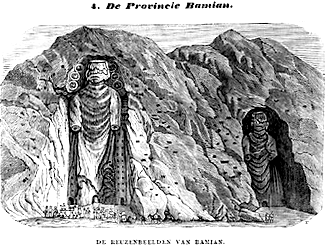

The dynamics between preservation and destruction have been playing out powerfully with the Buddhas of Bamiyan, Afghanistan. The two standing Buddhas were constructed in the sixth century C.E. along the Silk Road, where there were once many Buddhist monasteries. In 2001 the statues were destroyed by the Taliban who had expressed their intention to destroy the “infidel” monuments beginning in the late 1990s. The world community tried to convince Taliban leaders not to destroy them, but those efforts were not successful, and the Buddhas were dynamited over a period of about two weeks in March 2001. The niches in which the Buddhas once stood remain. Behind the niches are wall paintings, and evidence suggests that a third Buddha is still buried (figures 1.10 and 1.11).

“De Provincie Bamian.” Image from De Aardbol: Magazijn van heden daagsche land-en volkenkunde 9 (1839). Permission of Europeana

Bamiyan Buddha after March 11, 2001. Permission of Europeana

UNESCO inscribed the “Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley” a World Heritage Site in 2003. Since then, a UNESCO-funded project is sorting the fragments. Claudio Margottini, an engineering geologist for the conservation of cultural heritage, has edited a book on rehabilitating the site.28 The possibility of reconstructing at least one of the statues with the remaining fragments is under consideration, though some people have expressed doubt as to whether the statues should be rebuilt.29 (For an update, see chapter 10, Preservation: Enduring or Ephemeral?”)

Michael Falser, a research fellow and the chair of Global Art History at Heidelberg University in Germany, has suggested that the Taliban were protesting as much the globalizing concept of “cultural heritage” as they were the Buddhas themselves.30 In other words, an international approach to preservation may threaten regional hegemony or religious beliefs. In this sense, groups such as the Taliban and ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), also referred to as IS and ISIL (the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), are taking back what they see as “theirs” (all kinds of human-made objects and architectural sites); their view is that they own these things, which they believe gives them the right to destroy them. (This idea will be considered in more detail in chapter 4, “Documenting Cultural Heritage in Syria.”)

A Japanese-American artist, Hiro Yamagata, came up with another approach to recreating the site. A decade ago he designed a laser project (“Laser Buddhas”) that could be powered by windmills and solar panels. His aim was to “reproduce” the statues in holograms at the site. Images of his laser creations can be found on the web. While this project never came to fruition in Afghanistan, Yamagata has exhibited his installation.31 More recently, a Chinese couple, Janson Yu and Liyan Hu, have created a 3D Buddha laser projection light show to re-create the two Buddhas; images of their creation are available on the web.32 They received permission from the Afghan government and UNESCO to display the Buddhas in situ for one night: June 7, 2015.33 (New digital technologies are making it possible for tourists to “visit” historic sites that for preservation reasons are not open to the public. Such projects are described in chapter 7, “What Are We Really Trying to Preserve: The Original or the Copy?”) This goes beyond preservation to reimagining.

As the examples in this chapter show, there are as many attitudes and responses to preservation as there are cultures, governments, and political movements. An example of large-scale cultural genocide took place in Bosnia during the Balkan Wars of the 1990s with the destruction of the Bosnian National and University Library in Sarajevo, as well as other archives, libraries, and sites in the country.34 The large-scale destruction of monuments is taking place now in Iraq and Syria, mostly at the hands of ISIS. However, there is a new twist. ISIS doesn’t destroy all the antiquities that it steals: it sells many of them on the black market. The money supports the ISIS army. Therefore, it profits from the sales of small antiquities while destroying monumental structures that are too big to sell. The destruction makes for great PR for their cause, and ISIS seems to carefully record its plundering. Moreover, ISIS will kill anyone who attempts to thwart these objects’ destruction. Since 2014, conservators, lawyers, guards, curators, and arts administrators have been murdered in Iraq and Syria.35 Most recently, in August 2015, Islamic State militants beheaded the archeologist Khaled al-Asaad, an elderly scholar, in Palmyra, Syria. He apparently refused to disclose where valuable artifacts had been moved for safekeeping.36 Some monuments are simply beyond saving.

* * *

Strategies for preserving cultural heritage continue to evolve and are described throughout this book. Many professional organizations, foundations, and government agencies contribute to global preservation efforts. Yet new collaborative alliances are needed as well. Environmental historian Marcus Hall has called for “more conversations between restorationists of nature and of culture.”37 Among the professions that share the broad concerns elucidated in the definitions given at the beginning of this chapter, scholars in these fields do not necessarily communicate across professional domains. This is due in part to the fact that those with an interest in preservation—the term that I privilege in this book—work in different academic disciplines, attend different professional conferences, and publish in different venues. While there are ample examples of interdisciplinary work across these fields, this book seeks to open the door wider than it is now.

Two additional terms that are much used today need to be defined here: cultural heritage and cultural memory. What do they signify? John H. Stubbs, a historic preservationist, defines cultural heritage as

1. The entire corpus of material signs—either artistic or symbolic—handed on by the past to each culture and, therefore, to the whole of humankind.… 2. The present manifestation of the human past.… 3. Cultural Heritage possesses “historical, archaeological, architectural, technological, aesthetic, scientific, spiritual, social, tradition or other special cultural significance, associated with human activity.” 4 “Evidence of Cultural Value” at a site comes from “the comparative quality of a mixture of different factors: construction; aesthetics; usage/associations; context; and present condition.”38

Cultural heritage can also be defined more broadly to include the preservation of the tangible (monuments, buildings, works of art, books, documents) and the intangible (customs, beliefs, lore, unrecorded music, language). It refers to inheritance and legacy as well as to traditions. Cultural heritage emanates from particular societies at particular times, and is passed from one generation to the next. But much gets lost, and what is not lost will always be vulnerable to the vicissitudes of man and nature.39

Cultural memory is another term that is often used in association with preservation. It is the process of recalling what we have learned—individually and collectively. Philosophers have speculated about individual memory for some two thousand years.40 However, in the twentieth century, in the wake of World War I, art historian Aby Warburg and sociologist Maurice Halbwachs independently came up with ideas of a collective memory or social memory. Memory cannot be separated from the conditions in which it is formed—and later recalled. Jan Assmann further developed ideas about how collective knowledge evolved from socialization and customs. Eventually scholars referred to this scholarship as cultural memory. As Robert DeHart puts it, “…cultural memory represents a reconstructed past that serves the present needs of a group.… A group’s cultural memory is reinforced and transmitted to other individuals in forms such as commemorations, rituals, monuments, oral traditions, museum exhibits, books, and films.”41

The social process of memory is studied by scholars in many fields including history, literature, art history, psychology, cognitive sciences, computer science, and library, archives, and information studies. The preservation of heritage facilitates memory.

In Realms of Memory, Pierre Nora describes external sites of memory such as museums and monuments that can preserve historic links between people and historic events.42 However, the representation of past events is necessarily interpretive. Many have questioned the accuracy of particular interpretations. One example is Colonial Williamsburg (in Virginia), which has been subject to reinterpretation since its opening in the 1930s. Criticisms have included its commercialism, its neat-and-tidy facade, and its inaccurate portrayal of the African-American experience. Museum exhibitions have occasionally been subject to protests over “how we remember.” Perhaps the most famous episode in recent decades concerned the Enola Gay exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution, which had been meant to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. (The Enola Gay was the B-29 airplane that dropped the atomic bomb over Japan.) The initial exhibit was canceled as a debate ensued about how the museum should represent the history of the dropping of the bomb.

Such debates force us to consider what and how we preserve for the long term, not just the short term. While Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset play with the notion of “short term” in their “Powerless Structure,” figure 1.8, above, Yang Yueluan shows how the ruins of the Great Wall of China persist in the long term, but in new ways (figure 1.12). This book will consider the short- and long-term aspects of preservation.

Section of the Great Wall of China, Hebei Shanhaiguan, January 28, 2013, by Yang Yueluan. Courtesy of Elmar Seibel, Ars Libri

Notes