Chapter 5

Selecting the Best Home Purchase Loan

IN THIS CHAPTER

Choosing the right type of mortgage

Choosing the right type of mortgage

Understanding fixed, adjustable, hybrid, and other loan options

Understanding fixed, adjustable, hybrid, and other loan options

Making the 15-year versus 30-year decision

Making the 15-year versus 30-year decision

Dealing with periods of high mortgage interest rates

Dealing with periods of high mortgage interest rates

As you consider your mortgage options, you may quickly find yourself overwhelmed by the sheer number of choices. Should you choose a 15-year or a 30-year fixed-rate loan? What about mortgages that have variable interest rates — some adjust monthly, others every 6 or 12 months. Still others have a fixed interest rate for, say, the first one, three, five, seven, or ten years and then convert into some sort of adjustable rate. Or you can choose loans that start out as adjustable-interest-rate mortgages but allow you to elect at some future date to convert into a fixed-rate loan.

Most mortgages come with a number of bells and whistles, which means that literally tens of thousands of loan choices are available. Talk about a mortgage migraine! This chapter goes over the many options you can choose among and helps you select which ones work best for you.

Three Questions to Help You Pick the Right Mortgage

Here’s a clutter-busting pain reliever. Each and every possible mortgage you may consider falls into one of two major camps: fixed-rate mortgage or adjustable-rate mortgage (if these terms are foreign to you, be sure to read Chapter 4

). Later in this chapter, we delve into the details of fixed- versus adjustable-rate mortgages.

First, however, we want to help you separate the forest from the trees. Following are three questions you need to ask yourself as you weigh which type of mortgage is best for you.

How long do you plan to keep your mortgage?

From a financial perspective, this is the most important question. Many homebuyers don’t expect to stay in their current homes for a long time. If that’s your expectation, consider an adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM). Why? Because an ARM starts at a lower interest rate than a fixed-rate loan, so you will save interest dollars in the first few years of holding your ARM.

A mortgage lender takes more risk when lending money at a fixed rate of interest for a longer period of time. The longer the loan term, the more time lenders could experience that interest rates increase and their cost of securing funds from deposits and other sources rise. Thus, compared with an ARM, where the lender is committing to the initial interest rate for a relatively short period of time, lenders charge a premium interest rate for a fixed-rate loan.

The interest rates used to determine most ARMs are short-term interest rates, whereas long-term interest rates dictate the terms of fixed-rate mortgages. During most time periods, longer-term interest rates are higher than shorter-term rates, because of the greater risk the lender accepts in committing to a longer-term rate.

The interest rates used to determine most ARMs are short-term interest rates, whereas long-term interest rates dictate the terms of fixed-rate mortgages. During most time periods, longer-term interest rates are higher than shorter-term rates, because of the greater risk the lender accepts in committing to a longer-term rate.

The downside to an ARM, however, is that if interest rates rise, you may find yourself paying more interest in future years than you would be paying had you taken out a fixed-rate loan from the get-go. If you’re reasonably certain that you’ll hold onto your home for five years or less, however, you may come out ahead with an adjustable-rate mortgage.

If you expect to hold onto your home and mortgage for more than five to seven years, a fixed-rate loan may make more sense, especially if you’re not in a

financial position to withstand the fluctuating monthly payments that come with an ARM. If you’re expecting to stay five to ten years, consider the hybrid loans we discuss in the “Fixed-rate periods on ARMs

” sidebar, later in this chapter.

How much financial risk can you accept?

Many homebuyers, particularly first-timers, take an adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) because doing so allows them to stretch and buy a more expensive home. We Americans aren’t well known for our delayed gratification discipline! Also, real estate agents and mortgage brokers (also known as salespeople), who derive commissions either from the cost of the home you buy or the size of the mortgage you take on, may encourage you to stretch. So, if you haven’t already done so, please be sure to read Chapter 1

to understand how much you can really afford to borrow given your other financial needs, commitments, and goals.

If you’re considering an ARM, you absolutely, positively must understand what rising interest rates — and, therefore, a rising monthly mortgage payment — can do to your personal finances. Consider taking an ARM only if you can answer yes to all the following questions:

- Is your monthly budget such that you can afford higher mortgage payments and still accomplish other important personal financial goals, such as saving for retirement, your children’s future educational costs, vacations, and the like?

- Do you have an emergency reserve or “rainy day” fund, equal to at least three to six months of living expenses, which you can tap into to make the potentially higher monthly mortgage payments?

-

Can you afford the highest payment allowed on the adjustable-rate mortgage? The mortgage lender can tell you the highest possible monthly payment, which is the payment you’d owe if the interest rate on your ARM went to the lifetime interest-rate cap allowed on the loan.

Never take an ARM without understanding and being comfortable with your ability to handle the highest payment allowed. Prior to the real estate market downturn just before and after the financial crisis and severe recession of 2008, many lenders qualified borrowers for an ARM if they could pay the artificially low initial loan payments. Now lenders are far more likely to qualify you for an ARM based on your ability to afford the maximum loan payment you may have to make.

Never take an ARM without understanding and being comfortable with your ability to handle the highest payment allowed. Prior to the real estate market downturn just before and after the financial crisis and severe recession of 2008, many lenders qualified borrowers for an ARM if they could pay the artificially low initial loan payments. Now lenders are far more likely to qualify you for an ARM based on your ability to afford the maximum loan payment you may have to make.

- If you’re stretching to borrow near the maximum the lender allows or an amount that will test the limits of your budget, are your job and income stable? If you’re a two-income household, can you keep making loan

payments if one of you loses your job? If you expect to have children in the future, remember that your household expenses will rise and your disposable income may fall with the arrival of those little bundles of joy.

- Can you handle the psychological stresses of dealing with changing interest rates and mortgage payments?

If you’re fiscally positioned to take on the financial risks inherent to an ARM, by all means consider one. As we discuss in the previous section, odds are you can save money in interest charges with an ARM. Relative to a fixed-rate loan, your interest rate should start lower and should stay lower if the overall level of interest rates doesn’t change.

Even if interest rates do rise, as they inevitably and eventually will, they inevitably and eventually will come back down. So if you can stick with your ARM through times of high and low interest rates, you should still come out ahead.

Although ARMs do carry the risk of a fluctuating interest rate, as we discuss in the “Adjustable-Rate Mortgages (ARMs)

” section, later in this chapter, almost all adjustable-rate loans limit, or cap,

the rise in the interest rate allowed on your loan. Typical caps are 2 percent per year (annual cap)

and 6 percent over the life of the loan (life cap).

Consider an adjustable-rate mortgage only if you’re financially and emotionally secure enough to handle the maximum possible payments over an extended period of time. ARMs work best for borrowers who take out smaller loans than they’re qualified for or who consistently save more than 10 percent of their monthly incomes. If you do choose an ARM, make sure you have a significant cash cushion that’s accessible in the event that rates go up.

Consider an adjustable-rate mortgage only if you’re financially and emotionally secure enough to handle the maximum possible payments over an extended period of time. ARMs work best for borrowers who take out smaller loans than they’re qualified for or who consistently save more than 10 percent of their monthly incomes. If you do choose an ARM, make sure you have a significant cash cushion that’s accessible in the event that rates go up.

How much money do you need?

One factor that distinguishes the best mortgage from inferior loans is that the best mortgage is the best deal you can get. Why waste your hard-earned money on a mediocre mortgage? That’s not why you bought this book. The amount of money you borrow can greatly affect your loan’s interest rate. That’s why it behooves you to carefully consider how much money you need.

As we point out in Chapter 4

, conventional mortgages that stay within Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loan limits established each year by Congress are called conforming loans.

Mortgages that exceed the maximum permissible loan amounts are referred to either as jumbo conforming loans

, nonconforming loans,

or jumbo loans.

For example, the conforming loan limit for single-family dwellings in the continental United States was $424,100 when this book went to press. Because mortgage maximums change annually, however, be sure to check with your lender for the current Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loan limits. If the mortgage you need far exceeds the present conforming loan limit, skip the rest of this section. If, however, your loan is within 10 percent or so of the loan limit, keep reading. Our forthcoming advice may save you major money.

Why are we making such a fuss about the loan limit? Because mortgage interest rates for conforming loans typically run anywhere from ¼ to ½ percent lower

than the interest rates for jumbo loans. Keeping the amount of money you borrow under that all-important loan limit saves you big bucks over the life of your loan.

If your mortgage slightly surpasses Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s loan limit, we know three ways to bring it into conformity:

If your mortgage slightly surpasses Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s loan limit, we know three ways to bring it into conformity:

-

Spend less on a home.

This may seem obvious, but what the heck, we’ve never been accused of subtlety! The less you pay for a home, the smaller your mortgage.

-

Increase your down payment to reduce the mortgage.

We include a long list of cash cows you may be able to milk in Chapter 2

.

-

Use 80-10-10 financing.

Chapter 6

has an extremely enlightening section about 80-10-10 financing techniques you may be able to use to cut your first mortgage down to size.

Now, get down to the brass tacks of understanding the major features of fixed-rate versus adjustable-rate mortgages. Keeping the previous three questions in mind (How long do you plan to keep your mortgage? How much risk can you handle? How much money do you need?), read the following sections and ponder which mortgage works best for you.

Fixed-Rate Mortgages: No Surprises

As you may have surmised from the name, fixed-rate mortgages have interest rates that are fixed (that is, the rate doesn’t change) for the entire life of the loan, which is typically 15 or 30 years. With a fixed-rate mortgage, the interest rate stays the same, and the amount of your monthly mortgage payment doesn’t change. Thus, you have no surprises, no uncertainty, and no anxiety over possible changes in your monthly payment as you have with an adjustable-rate mortgage.

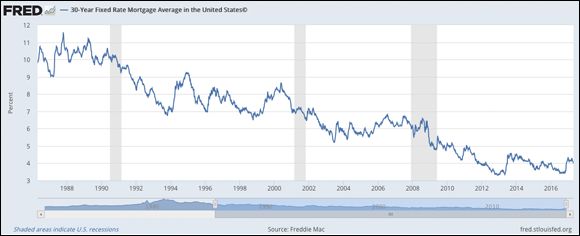

Figure 5-1

illustrates how 30-year fixed-rate mortgage interest rates have fluctuated over the years. You can bet with 100 percent certainty that they’ll continue to bounce up and down due to ever-changing economic conditions. However, we promise that once you have your very own 30-year fixed-rate loan, its interest rate won’t ever change.

Because the interest rate doesn’t vary with a fixed-rate mortgage, the advantage of a fixed-rate mortgage is that you always know what your monthly payment is going to be. Thus, budgeting and planning the rest of your personal finances is easier.

That’s the good news. The bad news, as we allude to earlier in this chapter, is that with a fixed-rate mortgage, you pay a premium, in the form of a higher interest rate, to get a lender to commit to lending you money at a fixed rate over the full term of the mortgage. The longer the term for which a mortgage lender agrees to accept a fixed interest rate, the more risk that lender is taking.

In addition to paying a premium interest rate when you originally get a fixed-rate loan, another potential drawback to fixed-rate loans is that, if interest rates fall significantly after you have your mortgage, you face the risk of being stuck with your costly mortgage. That could happen if, for example, due to problems with your personal financial situation or a decline in the value of your property, you don’t qualify to refinance, a topic we cover in Chapter 11

. Even if you do qualify to refinance, doing so takes time and costs money (appraisal, loan fees, and title insurance).

Here are a couple of other possible drawbacks to be aware of with some fixed-rate mortgages:

- Fixed-rate mortgages aren’t generally assumable, so if you sell during a period of high interest rates, your buyers must obtain their own financing. Finding assumable ARMs, however, is difficult.

- As with some adjustable-rate mortgages, some fixed-rate mortgages have prepayment penalties (see Chapter 4

for an explanation).

Adjustable-Rate Mortgages (ARMs)

Adjustable-rate mortgages

(ARMs) have an interest rate that varies over time. On a typical ARM, the interest rate adjusts every 6 or 12 months, but it may change as frequently as monthly. Popular ARMs include hybrid loans

where the initial interest rate is locked in for the first three, five, seven, or ten years and then adjusts after that (see the sidebar “Fixed-rate periods on hybrid-ARMs

”).

As we discuss later in this chapter, the interest rate on an ARM is primarily determined by what’s happening to interest rates in general. Remember that interest rates are the “price” for the commodity or product known as cash money. If the price of borrowing money is increasing, then most interest rates are on the rise. In this scenario, the odds are that your ARM will also experience increasing rates, thus increasing the size of your mortgage payment. Conversely, when interest rates fall (as the price of money becomes cheaper usually due to less demand and more capital available in the market), ARM interest rates and payments eventually follow suit.

If the interest rate on your mortgage fluctuates, so will your monthly payment sooner or later. And therein lies the risk: Because a mortgage payment is probably one of your biggest monthly expenses (if not the

biggest), an adjustable-rate mortgage that’s adjusting upward can wreak havoc with your budget.

You may be attracted to an ARM or hybrid loan because it starts out at a lower interest rate than a fixed-rate loan and thus may enable you to qualify to borrow more. However, just because you can qualify to borrow more doesn’t mean you can afford to borrow that much, given your other financial goals and needs. See Chapter 1

for all the details.

The right reason to consider an ARM is because you may save money on interest charges and you can afford the risk of higher payments if interest rates rise. Because you accept the risk of an increase in interest rates, mortgage lenders cut you a little slack. The initial interest rate (also known as the teaser rate

) should be significantly less than the interest rate on a comparable fixed-rate loan. In fact, even with subsequent rate adjustments, an ARM’s interest rate for the first year or two of the loan is generally lower than a fixed-rate mortgage.

The right reason to consider an ARM is because you may save money on interest charges and you can afford the risk of higher payments if interest rates rise. Because you accept the risk of an increase in interest rates, mortgage lenders cut you a little slack. The initial interest rate (also known as the teaser rate

) should be significantly less than the interest rate on a comparable fixed-rate loan. In fact, even with subsequent rate adjustments, an ARM’s interest rate for the first year or two of the loan is generally lower than a fixed-rate mortgage.

Another important advantage of an ARM is that, if you purchase your home during a time of high interest rates, you can start paying your mortgage with the artificially depressed initial interest rate. If overall interest rates then decline, you can capture the benefits of lower rates without refinancing as your ARM adjusts lower.

Here’s another situation when adjustable-rate loans have an advantage over their fixed-rate brethren: If, for whatever reason, you don’t qualify to refinance your mortgage when interest rates decline, you can still reap the advantage of lower rates. The good news for homeowners who can’t refinance and who have an ARM is that they’ll receive many of the benefits of the lower rates as their ARM’s interest rate and payments adjust downward with declining rates. With a fixed-rate loan, by contrast, you must refinance to realize the benefits of a decline in interest rates.

The downside to an adjustable-rate loan is that if interest rates in general rise, your loan’s interest and monthly payment will likely rise, too. During most time periods, if rates rise more than 1 to 2 percent and stay elevated, the adjustable-rate loan is likely to cost you more than a fixed-rate loan.

Before you make any decision between a fixed-rate mortgage versus an adjustable-rate mortgage, please read the following sections for a crash course in understanding ARMs.

How an ARM’s interest rate is determined

Most ARMs start at an artificially low interest rate. Don’t select an ARM based on this rate because you’ll probably be paying this low rate for no more than 6 to 12 months, and perhaps for as little as 1 month. Like other salespeople, lenders promote the most attractive features of their product and ignore the negatives. The low starting rate on an ARM is what some lenders are most likely to tell you about because profit-hungry mortgage lenders know that inexperienced, financially constrained borrowers focus on this low advertised initial rate.

The starting rate on an ARM isn’t anywhere near as important as what the future interest rate is going to be on the loan. How the future interest rate on an ARM is determined is the most important issue for you to understand when evaluating an ARM — if you plan on holding onto your loan for more than a few months.

To establish what the interest rate on an ARM will be in the future, you need to know the loan’s index and margin, the two of which are added together.

So ignore, for now, an ARM’s starting rate and begin your evaluation of an ARM by understanding what index

it is tied to and what margin

it has.

What are the index and margin? We’re glad you asked!

Start with the index

The index

on an ARM is a measure of general interest rate trends that the lender uses to determine changes in the mortgage’s interest rate. For example, the one-year Treasury constant maturity index is a common index used for many ARMs (discussed in next section).

Suppose that the going rate on this index is approximately 2 percent. The indexes used on various ARMs theoretically indicates how much it costs the bank to take in money, for example, from people and companies investing in the bank’s various accounts, which the bank can then lend to you, the mortgage borrower.

The following sections explain the most common ARM indexes. Don’t worry about lenders playing games with the indexes to unfairly raise your ARM’s interest rate. Lenders don’t control any of the indexes we discuss. Furthermore, they’re easy to verify. If you want to check the figures, you can usually find these indexes in publications such as The Wall Street Journal

or see our recommended websites in Chapter 8

for online sources for this information.

TREASURY SECURITIES

The U.S. federal government is the largest borrower in the world. So it should come as no surprise that some ARM indexes are based on the interest rate that the government pays on some of its pile of debt. The most commonly used government interest rate indexes for ARMs are for one, three, five, and ten-year Treasuries.

The Treasury security indexes are volatile; they tend to be among the faster-moving ones around. In other words, they respond quickly to market changes in interest rates. Treasury indexes are good when interest rates are falling and lousy when rates head higher.

THE LONDON INTERBANK OFFERED RATE INDEX (LIBOR)

The London Interbank Offered Rate Index

(LIBOR) is an average of the interest rates that major international banks charge each other to borrow U.S. dollars in the London money market. Like the U.S. Treasury indexes, LIBOR tends to move and adjust quite rapidly to changes in interest rates.

This international interest-rate index became increasingly popular as more foreign investors bought American mortgages as investments. Not surprisingly, these investors like ARMs tied to an index that they understand and are familiar with.

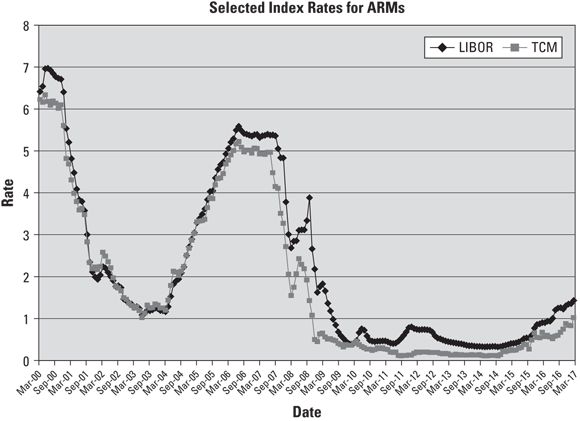

Be sure to ask your lender how the index tied to the ARM you’re considering has changed in the last five to ten years. Figure 5-2

helps you compare the volatility of the most common indexes.

Be sure to ask your lender how the index tied to the ARM you’re considering has changed in the last five to ten years. Figure 5-2

helps you compare the volatility of the most common indexes.

Add the margin

The margin,

or spread

as it’s also known, on an ARM is the lenders’ profit, or markup, on the money that they lend. Most ARM loans have margins of around 2.5 percent, but the exact margin depends on the lender and the index that lender is using. When you compare several loans that are tied to the same index and are otherwise the same, the loan with the lowest margin is better (cheaper) for you.

All good things end sooner or later. After the initial interest rate period expires, an ARM’s future interest rate is determined, subject to the loan’s interest rate cap limitations as explained later in this section, by adding together the loan’s current index value and the margin.

The following formula applies every time the ARM’s interest rate is adjusted:

For example, suppose that your loan is tied to the one-year Treasury security index,

which is currently at 2.5 percent plus a margin of 2.25 percent. Thus, your loan’s interest rate is

This figure is known as the fully indexed rate.

If a loan is advertised with an initial interest rate of, say, 3.5 percent, the fully indexed rate (in this case, 4.75 percent) tells you what interest rate this ARM would rise to if the market level of interest rates, as measured by the one-year Treasury security index, stays at the same level.

Always be sure to understand the fully indexed rate on an ARM you’re considering. To avoid any surprises, you also should know what the payment will be for various potentially higher interest rates during the life of your loan, including the maximum rate, so you fully understand what the maximum possible monthly payment is. Ask the lender and/or your mortgage broker to provide this payment information.

How often does the interest rate adjust?

Although some ARMs have an interest rate adjustment monthly, most adjust every 6 or 12 months, using the mortgage-rate determination formula discussed previously. In advance of each adjustment, the mortgage lender should mail you a notice, explaining how the new rate is calculated according to the agreed-upon terms of your ARM.

The less frequently your loan adjusts, the less financial risk you’re accepting. In exchange for taking less risk, the mortgage lender normally expects you to pay more — such as a higher initial interest rate and/or higher ongoing margin.

What are the limits on rate adjustments?

As discussed earlier in this chapter, despite the fact that an ARM has a formula for determining future interest rates (index + margin = interest rate), a good ARM limits the magnitude of change that can occur in the actual rate you pay. These limits, also known as rate caps,

affect each future adjustment of an ARM’s rate following the expiration of the initial rate period.

Two types of rate caps exist:

-

Periodic adjustment caps:

These caps limit the maximum rate change, up or down, allowed at each adjustment. For ARMs that adjust at six-month intervals, the adjustment cap is generally plus or minus 1 percent. ARMs that adjust more than once annually generally restrict the maximum rate change allowed over the entire year as well. This annual rate cap is typically plus or minus 2 percent.

-

Lifetime caps:

Never, ever, ever take an ARM without a lifetime cap. This cap limits the highest rate allowed over the entire life of the loan. ARMs commonly have lifetime caps of 5 to 6 percent higher than the initial start rate.

Without a lifetime cap, your possible loan payment could grow to the moon if interest rates soar again as they did in the early 1980s when rates peaked at more than 18 percent. Be sure you can handle the maximum possible payment allowed on an ARM if the interest rate rises to the lifetime cap.

Without a lifetime cap, your possible loan payment could grow to the moon if interest rates soar again as they did in the early 1980s when rates peaked at more than 18 percent. Be sure you can handle the maximum possible payment allowed on an ARM if the interest rate rises to the lifetime cap.

You may be wondering why we stress that interest rate adjustments are capped both up and down. Who cares how much rates can go down? You will, if rates drop rapidly and your ARM responds like molasses on a subzero winter morning. As we discuss in Chapter 11

, a good reason to refinance an ARM is to lower the periodic and lifetime adjustment caps accordingly if interest rates decline significantly.

You may be wondering why we stress that interest rate adjustments are capped both up and down. Who cares how much rates can go down? You will, if rates drop rapidly and your ARM responds like molasses on a subzero winter morning. As we discuss in Chapter 11

, a good reason to refinance an ARM is to lower the periodic and lifetime adjustment caps accordingly if interest rates decline significantly.

Does the loan have negative amortization?

On a normal mortgage, as you make mortgage payments over time, the loan balance you owe is gradually reduced through a process called amortization (see Chapter 4

).

Some ARMs, however, cap the increase of your monthly payment but don’t limit how much the interest rate can increase. Thus, the size of your mortgage payment may not reflect all the interest that you actually currently owe. So rather than paying the interest that’s owed and paying off some of your loan principal balance every month, you may end up paying some (but not all) of the current interest that you owe.

Thus, the extra, unpaid interest that you still owe is added

to your outstanding debt. This process of increasing the size of your loan balance is called negative amortization.

Negative amortization is like paying only the minimum payment required on a credit card bill. You continue accumulating additional interest on the balance as long as you make only the minimum monthly payment. However, doing this with a mortgage defeats the purpose of your borrowing an amount that fits your overall financial goals (as we discuss in Chapter 1

).

Some lenders try to hide the fact that an ARM they’re pitching you has negative amortization. How can you avoid negative amortization loans?

-

Ask.

As you discuss specific loan programs with lenders or mortgage brokers, be sure to tell them you don’t want a loan with negative amortization.

Specifically ask them if the ARM they’re suggesting has it or not.

You must be especially wary of being pitched negative amortization loans if you’re having trouble finding lenders willing to offer you a mortgage (in other words, you’re considered a credit risk). Remember Robert’s take on the old adage, “If it’s too good to be true, it’s too good to be true.

”

You must be especially wary of being pitched negative amortization loans if you’re having trouble finding lenders willing to offer you a mortgage (in other words, you’re considered a credit risk). Remember Robert’s take on the old adage, “If it’s too good to be true, it’s too good to be true.

”

-

If the loan has a monthly adjustment, ask again.

Monthly adjusting ARMs are often a warning sign of a negative amortization loan. Another red flag is an ARM with annual payment caps rather than semi-annual or annual interest rate adjustment caps.

Fine-Tuning Your Thought Process

Now that you know darn near everything worth knowing about fixed-rate mortgages and ARMs, you’re probably in a veritable frenzy of excitement about getting yourself preapproved for a loan. Not so fast, grasshopper. We have a few more words of wisdom for you.

Finding funds

Before you rush off, wouldn’t it be wise to find out where the money is? Here are the big sources for home purchase mortgages:

-

Conventional loans:

As noted in Chapter 4

, most U.S. residential mortgages are conventional loans originated by lending institutions such as banks, mortgage banks, credit unions, and mortgage brokers. Chapter 7

covers the merits of shopping for a loan yourself versus using a mortgage broker to assist you.

-

Government loans:

Low-income borrowers or folks with little or no cash for a down payment may be able to qualify for a variety of home loans either insured or guaranteed by an agency of the federal government. See Chapter 4

for additional information about Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and USDA Rural Development (RD) loans.

-

Seller loans:

These mortgages, which are generally referred to as owner-carry financing,

generally represent less than 5 percent of the loan market. They are, however, an extremely important loan source during periods of high mortgage interest rates and properties that may be more challenging to sell where the seller has a lot of equity. Owner-carry financing is usually structured as home purchase first mortgages, which we cover in Chapter 7

, or second mortgages (we’ve thought of everything — see Chapter 6

).

Almost all conventional first mortgages and government loans are fully amortized.

That means they’re designed to be repaid in full by the time you make the last regularly scheduled monthly payment. Darn near all owner-carry first mortgages, conversely, come due with a generally quite large unpaid balance. This type of

financing is called a balloon loan.

As noted in Chapter 6

, balloon loans can be extremely hazardous to your fiscal health if you can’t repay or refinance them when they’re due and payable — borrower beware!

Almost all conventional first mortgages and government loans are fully amortized.

That means they’re designed to be repaid in full by the time you make the last regularly scheduled monthly payment. Darn near all owner-carry first mortgages, conversely, come due with a generally quite large unpaid balance. This type of

financing is called a balloon loan.

As noted in Chapter 6

, balloon loans can be extremely hazardous to your fiscal health if you can’t repay or refinance them when they’re due and payable — borrower beware!

Making the 30-year versus 15-year mortgage decision

After you decide which type of mortgage — fixed or adjustable — you desire, you have one more major choice to make. Do you prefer a 15-year or a 30-year loan term? (You may run across some odd-length mortgages — such as 20- and 40-year mortgages; however, the issues we discuss in this section remain the same as when comparing 15-year to 30-year mortgages.)

If you’re stretching to buy the home of your dreams, you may not have a choice. The only loan you may qualify for is a 30-year mortgage. That isn’t necessarily bad and, in fact, has advantages.

The main advantage that a 30-year mortgage has over a comparable 15-year loan is that it has lower monthly payments that free up more of your monthly income for different purposes, such as saving for other important financial goals like retirement. You may want to have more money each month so you aren’t a financial prisoner in your abode. A 30-year mortgage has lower monthly payments because you have a longer time period to repay it (which translates into more payments). A fixed-rate, 30-year mortgage with an interest rate of 7 percent, for example, has payments that are approximately 25 percent lower than those on a comparable 15-year mortgage.

What if you can afford the higher payments that a 15-year mortgage requires? Should you take it? Not necessarily. What if, instead of making large payments on the 15-year mortgage, you make smaller payments on a 30-year mortgage and put that extra money to productive use?

If you do make productive use of that extra money, then the 30-year mortgage may be for you. A terrific potential use for that extra dough is to contribute it to a tax-deductible retirement account. Contributions that you add to employer-based 401(k) and 403(b) plans (and self-employed SEP-IRAs) not only give you an immediate reduction in taxes but also enable your money to compound, tax-deferred, over the years ahead. Another vehicle for tax-deductible contributions is the Health Savings Account (HSA) for those with higher deductible health plans. Everyone with employment income may also contribute to an Individual Retirement Account (IRA). Your IRA contributions may not be immediately tax deductible if your (or your spouse’s) employer offers a retirement account or pension plan, but they will grow tax-free.

If you’ve exhausted your options for contributing to retirement accounts and an HSA, and if you find it challenging to save money anyway, the 15-year mortgage may offer you a good forced-savings program. If you elect to take a 30-year mortgage, you retain the flexibility to pay it off faster if you so choose. (Just be sure to avoid those mortgages that have a prepayment penalty.) Constraining yourself with the 15-year mortgage’s higher monthly payments does carry a risk. If you stumble during tough financial times, you may not be able to meet the required mortgage payments.

Getting a Loan When Rates Are High

Over the years and decades, we’ve seen interest rates for conforming 30-year fixed-rate loans soar to more than 18 percent in the early 1980s and sink to a low of just over 3 percent in 2012. We can guarantee you with 100 percent certainty that mortgage rates will change. They always do. If we could only figure out a way to forecast how much and when, we’d be rich!

Earlier in this chapter, we point out three places to find a first mortgage with an interest rate significantly

lower than what you’d pay for a new, 30-year fixed-rate loan. Just to refresh your memory, here’s a recap:

-

ARMs:

Lenders charge a premium for fixed-rate loans. If you’ll share the lenders’ risk of possible future interest rate increases by getting an adjustable-rate mortgage, lenders will reward your adventurous spirit with a lower initial interest rate on your loan. The more often your loan adjusts, the lower your ARM’s initial interest rate. ARMs that adjust every six months, for example, generally have a lower start rate than ARMs that adjust annually and so on.

-

Loan assumptions:

It’s extremely unlikely that you’ll find a fixed-rate mortgage you can assume. On the other hand, some ARMs are assumable for creditworthy borrowers. Nuff said.

-

Seller financing:

Some long-term homeowners no longer have mortgages on their property. These fortunate folks may offer attractive financing to qualified buyers either to get a higher purchase price or to structure their transaction as an installment sale for preferable tax treatment by the IRS. (An installment sale provides that the buyer pays the purchase price, usually plus interest, in regular payments or installments over multiple tax years to spread out and reduce the tax consequences from the sale.)

Like it or not, you may have the monetary misfortune of buying your home during a period when mortgage rates are on the high side of the cycle. If that happens, don’t despair. You can refinance your loan when rates drop. Chapter 11

is chock-full of money-saving refinancing ideas.

Choosing the right type of mortgage

Choosing the right type of mortgage

Understanding fixed, adjustable, hybrid, and other loan options

Understanding fixed, adjustable, hybrid, and other loan options

Making the 15-year versus 30-year decision

Making the 15-year versus 30-year decision

Dealing with periods of high mortgage interest rates

Dealing with periods of high mortgage interest rates

The interest rates used to determine most ARMs are short-term interest rates, whereas long-term interest rates dictate the terms of fixed-rate mortgages. During most time periods, longer-term interest rates are higher than shorter-term rates, because of the greater risk the lender accepts in committing to a longer-term rate.

The interest rates used to determine most ARMs are short-term interest rates, whereas long-term interest rates dictate the terms of fixed-rate mortgages. During most time periods, longer-term interest rates are higher than shorter-term rates, because of the greater risk the lender accepts in committing to a longer-term rate. Never take an ARM without understanding and being comfortable with your ability to handle the highest payment allowed. Prior to the real estate market downturn just before and after the financial crisis and severe recession of 2008, many lenders qualified borrowers for an ARM if they could pay the artificially low initial loan payments. Now lenders are far more likely to qualify you for an ARM based on your ability to afford the maximum loan payment you may have to make.

Never take an ARM without understanding and being comfortable with your ability to handle the highest payment allowed. Prior to the real estate market downturn just before and after the financial crisis and severe recession of 2008, many lenders qualified borrowers for an ARM if they could pay the artificially low initial loan payments. Now lenders are far more likely to qualify you for an ARM based on your ability to afford the maximum loan payment you may have to make. Consider an adjustable-rate mortgage only if you’re financially and emotionally secure enough to handle the maximum possible payments over an extended period of time. ARMs work best for borrowers who take out smaller loans than they’re qualified for or who consistently save more than 10 percent of their monthly incomes. If you do choose an ARM, make sure you have a significant cash cushion that’s accessible in the event that rates go up.

Consider an adjustable-rate mortgage only if you’re financially and emotionally secure enough to handle the maximum possible payments over an extended period of time. ARMs work best for borrowers who take out smaller loans than they’re qualified for or who consistently save more than 10 percent of their monthly incomes. If you do choose an ARM, make sure you have a significant cash cushion that’s accessible in the event that rates go up.