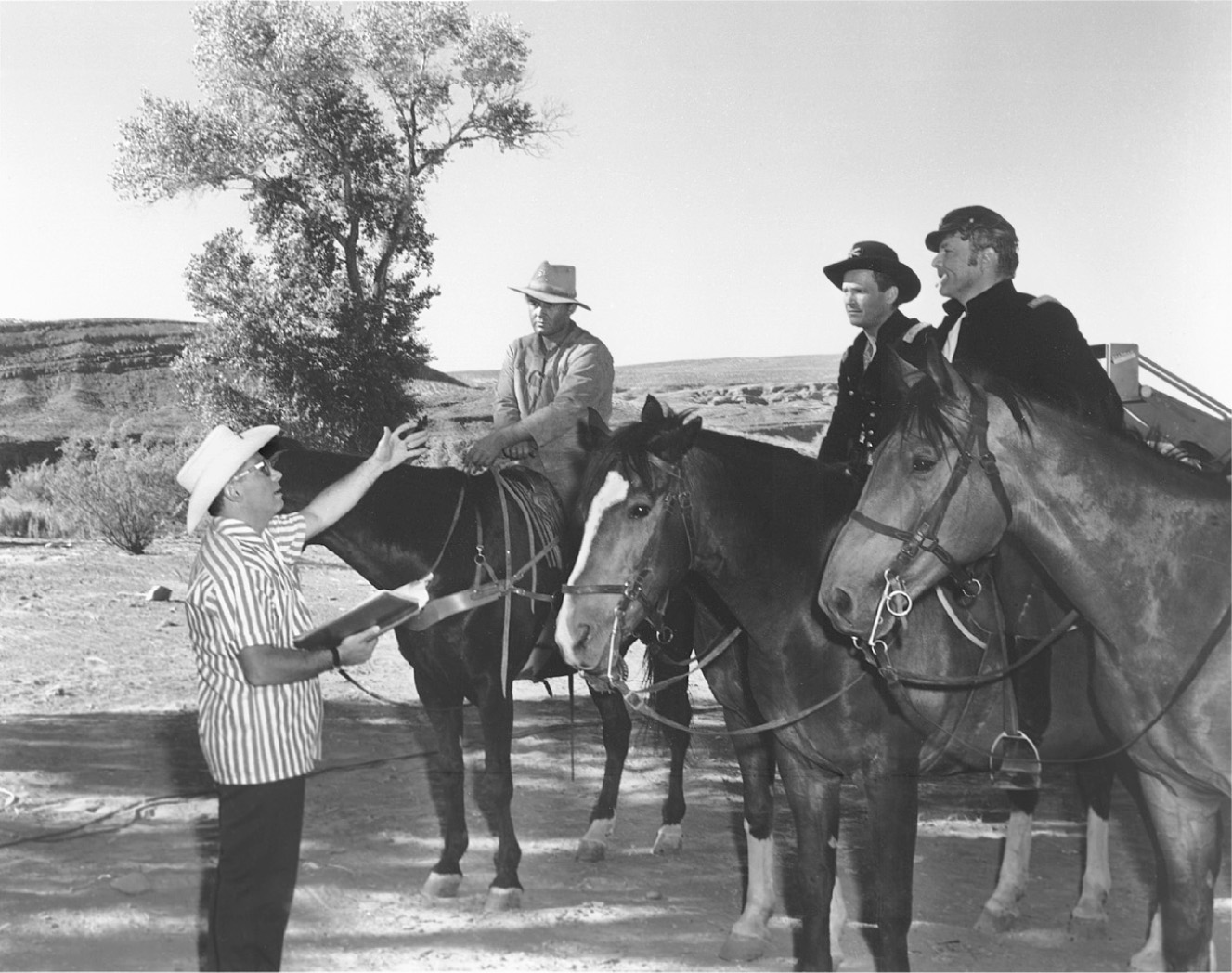

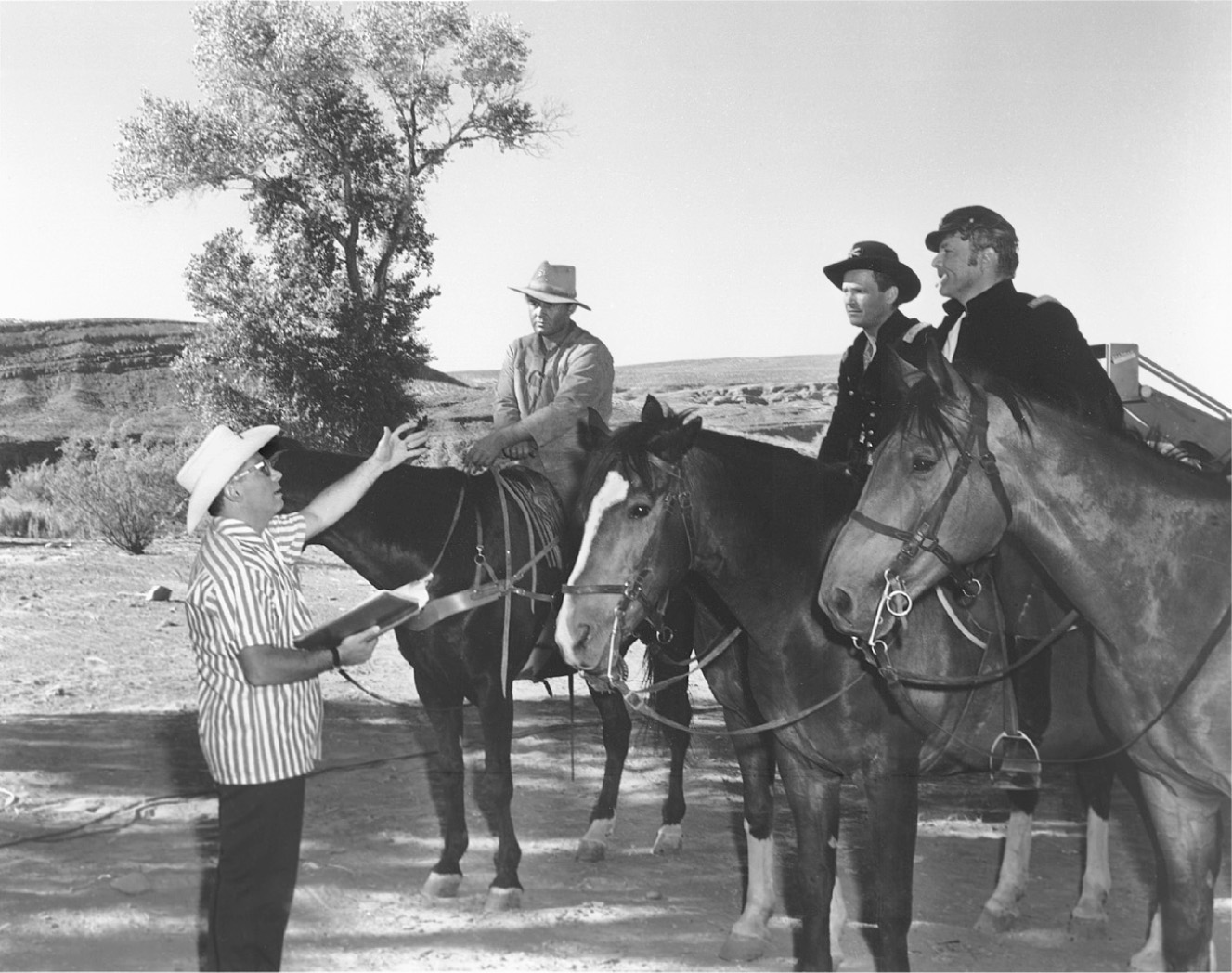

Samuel Fuller directs (left to right) Rod Steiger as O’Meara, Ralph Meeker as Lieutenant Driscoll, and Chuck Roberson as a cavalry sergeant on location in St. George, Utah, for Run of the Arrow. Author’s Collection

The Globe Years, 1956–1961

In the five years following his departure from Fox, Fuller produced films through Globe Enterprises, an independent company in which he had a 50 percent stake and complete control over production.1 Fuller served as producer, director, and writer of his Globe pictures and signed single and multiple picture contracts with RKO, Twentieth Century–Fox, and Columbia for financing and distribution. Fuller had big plans for Globe, hoping the company would eventually branch out into television and produce six films a year by a variety of directors.2 During this period Fuller stretched his aesthetic muscles, completing projects such as Run of the Arrow and Forty Guns, which were terminated while he was under contract at Fox, and freeing himself from the classical “quality controls” that so shaped his studio releases. His narratives were more loosely constructed, often contained politically or socially charged content, and featured jarring tonal shifts and offbeat displays of humor. His visual style was likewise more varied, combining extended long takes during conversation scenes with rapid editing during action. Conflict and kineticism came to the fore, often in sensationalistic ways.

While Globe provided Fuller with much greater control over his own material than he had at Fox and saddled him with less financial risk than he carried making Park Row, he still relied on steady box office returns in order to attract financing and distribution agreements. In the late 1950s, as the market for programmers continued to constrict, steady box office was difficult to find. Producers were primarily making action-oriented films as blockbusters with big budgets, major stars, exotic locations, color, and widescreen, while low-budget filmmaking became increasingly dominated by exploitation pictures designed to appeal to the youth market. Television became the new home for inexpensive genre narratives that could appeal to the whole family. Fuller responded to these industrial trends by largely staying the course, producing offbeat action films from original scripts while ratcheting up the sex and violence. Although both Twentieth Century–Fox and Columbia appear to have contemplated four Fuller releases each, poor box office led to only two films being distributed by each company, while RKO completely dissolved during the production of Verboten! and neither of the television pilots shot by Fuller were picked up. By 1961, Globe Enterprises was effectively finished.

The Challenges of Independence

As it became less expensive and less risky during the 1950s for the major studios to finance and distribute films made by outside producers, the centralized production of the studio system gave way to individually packaged films, increasing the number of “independent” pictures and multiplying the power of talented directors, agents, and stars. Under the new system, a producer brought together a story, financing, cast, crew, production facilities, and materials, relying on the major studios only for financing and/or distribution. A significant amount of time went into developing each project, as producers no longer relied on the studios to provide all the talent and equipment—now the means of production had to be assembled fresh for each film. The difficulty of orchestrating all of the necessary elements of production meant that films frequently collapsed before they were ever shot, forcing producers to develop multiple projects simultaneously in order to maintain consistent output.3

Although independent producers faced common responsibilities and challenges, their administrative power and creative freedom varied widely. Independent producers made a single feature or at most a few films a year; they had no direct corporate relationship to a distributor, although they might have had an ongoing distribution contract.4 While many variations of independent production flourished in the 1950s and 1960s, a 1957 article in Motion Picture Herald identified three main types of indies based on their financing arrangements.5 Total independents financed their own productions with their own money and enjoyed the most complete autonomy. Because few had the long-term careers of men like Samuel Goldwyn or Walt Disney, however, this form of independent production was the most rare. The second group of indie producers invested some of their own money into production, along with the advance granted by the distributor of the film. Members of this group had widely varying degrees of autonomy depending on the level of their investment and contract stipulations. The third arrangement, and also the most common, included independent producers who obtained their entire financing from distributors and who therefore were bound by whatever controls the distributor stipulated. These producers shouldered the least financial risk but also wielded the least power.

Because of financing and contractual arrangements, the actual independence of independent producers could be quite circumscribed.6 When considering loan requests for independent productions, banks considered the track record and fiscal responsibility of the producer, the experience of the director, the reputations of the cast and crew, and the box-office potential of the film. Banks required a distribution contract and completion bond even before negotiations began and often reserved approval of the script, cast, and budget.7 As a result, film packages with untested directors, unknown casts, or highly controversial subjects typically had a difficult time receiving financing. In addition, independent producers had to adhere to distributor contracts that specified preferred running times, PCA requirements, and the right of the distributor to re-edit the film for television or foreign exhibition; some contractual arrangements granted distributors even further creative control and the final cut. The financing and distribution system for independent productions therefore rarely resulted in big-budget films that operated outside of classical norms; more offbeat fare required the producer to assume a greater share of the financial risk and to demonstrate a viable market for the film.

Independent producers thus found long-term survival in the marketplace quite risky and were often forced to spend more time securing financing than actually making movies. While indie producers gained some flexibility and creative control, most nevertheless still relied on the banks and major studios for cofinancing, production resources, and access to distribution and first-run exhibition. In addition, since independent producers usually deferred their salaries in return for up to 50 percent of the profits, they only made money if their films made money—and over half of all films did not. Directors who functioned as their own producers, as Fuller frequently did, therefore found themselves more reliant on box-office success as an independent than most were accustomed to as contract directors for studios or smaller independent outfits. A series of films that failed as A features or proved too expensive to return a profit through distribution as Bs could cost an independent producer financing and distribution for subsequent films.

Despite the reduction of B releases by the major and minor studios, the need to fill double bills maintained the market for very low-budget films into the early 1960s. Programmers, rather than true Bs, faced the greater challenge at the box office, both at home and abroad. The studios’ move toward blockbuster films with high production values made it more difficult for “in-betweeners” to compete as A product—especially within action-adventure genres, now tracking toward the epic—while the flat rental rates awarded to the programmer demoted to the bottom half of the bill virtually guaranteed a profit loss.8 As the market in the mid-1950s increasingly split into high-budget and very low-budget tracks, Columbia, Universal, and United Artists released a handful of highly successful low-budget films, and by 1956 Twentieth Century–Fox, MGM, Republic, and Allied Artists also began producing or distributing a limited number of inexpensive black-and-white pictures.9 Typically featuring CinemaScope for added production value, these films fit neatly into the western, horror, crime, and science fiction genres, as well as the fastest-growing genre of them all, the teenpic.

Rapidly becoming a powerful presence in the consumer marketplace, teenagers formed the target audience for budget filmmakers in the 1950s and 1960s. In response to the astonishing success of producer Sam Katzman’s Rock Around the Clock (1956), low-budget outfits such as American International Pictures (AIP) cranked out topical movies for the youth market in genres indebted to traditional B films. Recognizing the difficulty in turning a profit by distributing B pictures for a flat rental fee, AIP bundled inexpensive action-oriented films into same-genre double bills and sold them to states’ rights franchises as a unit for a percentage of the box office. Arguing that the market for mid-budget films had dried up, the company positioned itself to fill exhibitor needs in between screenings of blockbusters.10 The sensational advertising used by AIP and like-minded producers prompted Variety to categorize their product as teen exploitation: “These are low-budget films based on controversial and timely subjects that make newspaper headlines. In the main, these pictures appeal to ‘uncontrolled’ juveniles and ‘undesireables.’”11

The difficulty of surviving in the low-budget market without appealing to teens is illustrated by the struggles of director Robert Aldrich’s independent production company, Associates and Aldrich, during the late 1950s. The financial success of his first pictures as a director, Apache (1954), Vera Cruz (1954), and Kiss Me Deadly (1955), enabled Aldrich to form Associates and to continue his involvement with United Artists, the distributor of his first three films.12 After its retrenchment in 1951, UA began an aggressive campaign of offering independent producers complete production financing, creative autonomy, and profit sharing in exchange for distribution.13 Aldrich’s proven ability to deliver profitable films on time and under budget convinced UA to finance and distribute the Associates and Aldrich productions The Big Knife (1955), an adaptation of a scathing Clifford Odets’s play about Hollywood, and Attack (1956), a grim World War II combat picture, both budgeted for less than $500,000. Neither film made money, however, and after a disastrous three years spent clashing with Harry Cohn while under contract at Columbia, Aldrich found himself nearing bankruptcy by the end of the decade.14 When UA pulled financing for his dream project, Taras Bulba, a Nikolai Gogol adaptation slated to star Anthony Quinn, Aldrich was forced to direct television dramas and to freelance in Europe. Despite his desire to produce more artistic projects, Aldrich’s slide from box-office success to near bankruptcy in the 1950s convinced him to pursue a production strategy in the 1960s geared toward generating secure returns and guaranteeing his ability to make the next picture. “If I weren’t wearing both hats, I’d like to make a picture that would free Angela Davis,” he said. “But I don’t want the producer part of me to lose so much money that he can’t make the next one.”15 By recognizing his reliance on box-office returns and developing multiple properties at a time, Aldrich kept his independent production company afloat for seventeen years and fourteen films, eventually making multimillion dollar action-adventures such as The Flight of the Phoenix (1965) and The Dirty Dozen (1967). Although his films did not directly appeal to the teen market, Aldrich’s hard-headed realism kept him working when many of his postwar low-budget contemporaries, including Fuller, struggled to complete pictures.

By the early 1960s, the market for low-budget B films was increasingly restricted to the bottom half of the few remaining double bills at first-run theaters and to the secondary-run and drive-in circuit. Programmers and medium-budget films continued to be made but were rapidly becoming “a vanishing breed.”16 The examples of Associates and Aldrich and AIP suggest that in order to find bookings and make a profit, smaller companies and independent producers either had to craft accessible films with guaranteed returns or had to stay one step ahead of the major and minor studios through exploitation of gimmicks and cutting-edge cultural trends. If producers competed directly with the studios in popular genres, then stars, larger budgets, and higher production values were necessary for success. In addition, films that appealed to teens through the use of youth-oriented actors, genres, or humor—as demonstrated in those pictures released by AIP—sported an advantage in the low-budget market, both due to the high percentage of youth in the moviegoing population and to their preference for double bills and drive-ins, now the primary homes of low-budget material.17 As Fuller ventured into independent production in the late 1950s, his best bets for box-office success were thus glossy, star-filled blockbusters or lower-budget, topical teenpics; instead, he largely took the middle path, producing programmers for adults despite the limitations of the market.

No Holds Barred: Run of the Arrow,

China Gate, Forty Guns, and Verboten!

Fuller’s first Globe picture, Run of the Arrow, originated as a script Fox declined to produce; it went into production with RKO in the summer of 1956, even before Fuller’s option contract with Fox was officially terminated. RKO greatly reduced studio output during the 1950s and was relying heavily on independent product to keep itself afloat. In his autobiography, Fuller describes pitching RKO studio head William Dozier, who greenlit Run of the Arrow subject to approval of the principal cast. Although Dozier lobbied for Gary Cooper to play the lead, a Yankee-hating Southerner who heads west after the Civil War, Fuller fought hard for up-and-comer Rod Steiger, as his “sour face” more accurately suggested the character’s status as a “sore loser.”18 Fuller shot Run of the Arrow in Technicolor and masked widescreen for five weeks on location near St. George, Utah, with a budget of $1 million, his highest for any Globe production.19 The film teamed Fuller with cinematographer Joseph Biroc, a veteran of Robert Aldrich and John Ford films, and editor Gene Fowler, Jr., who previously cut for Fritz Lang; both men continued to work with Fuller on his Globe pictures for Twentieth Century–Fox, China Gate and Forty Guns. As was his tendency, Fuller grounded his ideas for Run of the Arrow in substantive research, seeking to portray the Sioux in a more respectful and realistic fashion than was the norm in Hollywood. The official press release differentiates the film from others in the genre by describing it as “an epic Western which has nothing to do with cowboys, rustlers, dishonest sheriffs or pretty schoolteachers.… [I]t is one of the few motion pictures to bring to the screen American Indian life with complete authenticity.”20

With its unified plot structure, focus on the legacy of the Civil War and Sioux culture, and mediating female character who is a romantic helpmate, Run of the Arrow does in fact engage genre conventions—particularly those circulating in post–Civil War cavalry and American Indian pictures like John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948)—and it does so more fully than Fuller’s other westerns. The film begins with O’Meara (Steiger), a Confederate soldier, firing the last shot of the Civil War before he hears of Lee’s surrender. O’Meara merely wounds the Union soldier, Driscoll (Ralph Meeker), and bitterly holds onto the warped bullet, an ugly reminder of what he views as the South’s capitulation. Refusing to live under Yankee dominion, O’Meara heads west to the frontier, where he meets an aging Sioux army scout (Jay C. Flippen) who teaches him the ways of his tribe. The two are set upon by a young Sioux warrior, Crazy Wolf (H. M. Wynant), who challenges them to the run of the arrow, a footrace in which a barefoot runner is given a head start equal to the length of an arrow in flight. The Sioux scout collapses during the run, but O’Meara outpaces Crazy Wolf and is ultimately hidden by Yellow Moccasin (Sarita Montiel), a Sioux maiden. O’Meara and Yellow Moccasin marry, and O’Meara is welcomed into the Sioux community by its chief, Blue Buffalo (Charles Bronson). When the United States and the Sioux sign a peace treaty, O’Meara is hired as a scout attached to an army fort. He finds Blue Buffalo’s wisdom and tolerance mirrored in Captain Clark (Brian Keith), the soldier in command of the army detachment, but Clark is killed by Crazy Wolf, leaving O’Meara’s Civil War nemesis, Lieutenant Driscoll, in charge. O’Meara forces Crazy Wolf to answer for Clark’s death through the run of the arrow, but hotheaded Driscoll interferes with the run and shoots Crazy Wolf, prompting the Sioux to attack the army fort. The Sioux burn the fort and proceed to skin Driscoll alive, until O’Meara responds by putting a bullet in the lieutenant’s head—the same bullet he tried to kill Driscoll with at the beginning of the film. Rethinking where his loyalties lie, O’Meara heads east with Yellow Moccasin at the close of the picture, accompanied by the final title: “The end of this story can only be written by you.”

Run of the Arrow is one of Fuller’s most overt explorations of identity and allegiance and makes strong use of motifs and parallels to structure narrative meaning. O’Meara attempts to enact the myth of the frontier as an opportunity for renewal and reinvention, but his past proves difficult to shake. Though he finds love and purpose among the Sioux, he hesitates with the question they repeatedly ask him: “Would you kill an American in battle?” As is typical of Fuller’s female helpmates, Yellow Moccasin figures it out first, telling O’Meara: “You will always be unhappy as a Sioux. You were born an American.” O’Meara is left unable to deny the values that have shaped him; he embraces the ritual nobility of the run of the arrow, but draws the line at flaying a man alive. Fuller carefully charts O’Meara’s struggle through the motifs of the run and the bullet, each of which appear twice in the narrative. During the runs of the arrow, O’Meara is first victim of the Sioux and then defender of Sioux honor; as the assailant of Driscoll, O’Meara shoots initially in anger and finally in pity—he is not Sioux, after all, but American. The pairings of Blue Buffalo–Captain Clark and Crazy Wolf–Driscoll underline O’Meara’s ultimate choice as one based not on an assumption of cultural superiority, but rather on the recognition of innate identity: both the Sioux and the Americans are capable of producing men of reason and men of hatred. With his open-ended epilogue, Fuller reminds viewers that it is up to us to champion reason over hatred, to heal ourselves as a step toward healing our own nations.

Run of the Arrow marks a return to a less classical visual style for Fuller, and he adopts a variety of stylistic strategies to provoke viewers both intellectually and emotionally. Gone is the tendency, most evident in Hell and High Water, to construct scenes with full coverage, cutting from establishing shots to medium shots and in to close-ups for emphasis. Instead, Fuller intercuts shots of varying distance from the camera in more unusual scene dissection. Six scenes contain extreme long takes of over a minute and a half, a length far exceeding Hollywood’s widescreen average shot length of nine to twelve seconds. As with the exceptional four-minute, forty-two-second shot of Captain Clark telling O’Meara why it is important to fight for the United States, these lengthy takes tend to be largely static and reserved for weighty discussions that explore the film’s central themes. By stripping the frame of movement and competing points of interest, Fuller forces the viewer to focus on the conversations at hand; his confidence in his message seems to outweigh any fear of viewer boredom. Long takes are balanced throughout the film by visceral sequences more reliant on editing, a dynamic last seen in Park Row. The constructive editing Fuller used in the openings of I Shot Jesse James, The Steel Helmet, and Pickup on South Street becomes central to his presentation of the run of the arrow, while the most brutal sequence in the film, the skinning of Driscoll, relies heavily on montage to represent indirectly that which cannot be explicitly shown.

The presentation of Crazy Wolf’s pursuit of O’Meara and the old Sioux scout during the first run of the arrow is a prime example of Fuller’s ongoing tendency to use constructive editing, match cuts, and graphic contrasts in order to create dynamic sequences of expressive motion. Fuller intercuts tracking medium shots of each man, framed from the waist down running from right to left. Each pair of legs is centered in the frame, producing a series of matching shots and making the identity of each man ambiguous. Rather than clarifying who is who and how far away the men are from each other—a logical choice during a chase scene—the editing and framing primarily function to create pairs of legs that are mirror images and to emphasize motion itself. Fuller was especially fond of depicting disembodied legs running or walking, and similar sequences appear in The Steel Helmet, Fixed Bayonets, Forty Guns, The Crimson Kimono, Underworld, U.S.A., and Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street.

In addition to the two runs of the arrow, the most heavily edited scene in the film is the attack on the army fort and the skinning of Driscoll. Here Fuller utilizes visual ellipses, constructive editing, quick cuts, and offscreen sound in order to address PCA objections to the scene’s brutality while still exploiting its sensational impact. PCA administrator Geoffrey Shurlock objected to the torture and death of Lieutenant Driscoll in the script of Run of the Arrow as “a justification of mercy killing” and claimed it was too much “dramatized”: “It is one thing to establish this inhuman torture and another thing to revert constantly to close-ups of Driscoll’s face showing the excruciating agony of the man.”21 The sequence as it appears in the film obligingly avoids constant close-ups of Driscoll, while nevertheless featuring editing and sound that actually intensify the suspense and thrills of the sequence. The scene immediately highlights Driscoll’s torture and impending execution by opening with a high-angle shot that cranes down as the Sioux tie Driscoll to a stake and rip his shirt open. A cut to a medium-close shot focuses attention on Driscoll’s face as Crazy Wolf slices the lieutenant’s throat, producing a stream of Technicolor blood. Driscoll screams, cueing a series of cutaways to O’Meara and the Sioux. O’Meara repeatedly turns away in close-up, with Driscoll’s agonized cries echoing across each shot. O’Meara finally takes out his bullet, silently loads his gun, and shoots; in an extreme close-up, Driscoll’s sweaty, bloodied face recoils as a whiff of smoke marks the entry of the bullet into his head. The entire sequence lasts nearly a minute and a half, with Driscoll’s wailing covering two-thirds of the sequence.

Samuel Fuller directs (left to right) Rod Steiger as O’Meara, Ralph Meeker as Lieutenant Driscoll, and Chuck Roberson as a cavalry sergeant on location in St. George, Utah, for Run of the Arrow. Author’s Collection

By cutting away to O’Meara’s reaction shots as well as those of Blue Buffalo watching O’Meara watching Driscoll, the sequence actually prolongs Driscoll’s agony, encouraging the viewer to speculate how he is being tortured. While close-ups of Driscoll’s face would have underlined his pain, emphasizing O’Meara’s reaction more effectively suggests a torture of unspeakable dimensions, one so heinous that it prompts O’Meara to break his pledge of loyalty to the Sioux and take pity on a man he despises. The final close-up of Driscoll, quite graphic in its specificity, further underlines the horror of the torture—if putting a bullet in a man’s forehead is an act of pity, then the alternative must truly be foul. As enacted in the film, Shurlock’s suggestion neither softened the brutality of the sequence nor toned down the mercy killing; if anything, both points were intensified by the alternatives Fuller chose. Because of its use of stylistic techniques that heighten the impression of extreme suffering, this sequence is an excellent example of how Fuller’s films often bypassed PCA restrictions through indirect representation in order to retain their visceral impact. Critics duly noted the shocking power of the violence, with Variety describing the film as “pretty rough at times, especially for the squeamish.”22

Run of the Arrow was the best positioned of all of Fuller’s Globe pictures to achieve box-office success. The cast, use of Technicolor, and location photography lent the film top-flight production values, while its promotional campaign stressed its originality. In addition, the film enjoyed an extended release accompanied by a national advertising campaign indicative of its intended status as an A picture. With steady first-run distribution by Universal-International on behalf of RKO, the film played a range of downtown houses, drive-ins, and neighborhood theaters from July to November 1957. During its initial month of release, full-page ads ran in Look and Life, and a national billboard campaign targeted sixty-nine major markets in support of a saturation booking strategy.23 The film modestly premiered first-run in two small seaters and two drive-ins in Kansas City, booked with a pair of second-run RKO releases. Exhibitors reported that the box office “looks good,” and critics gave Run of the Arrow acceptable and even enthusiastic reviews, particularly noting the Technicolor bloodletting and the film’s appeal to the outdoor market.24 The film opened the following week at the 1,700-seat Palace in New York City and subsequently played across the country, consistently screening solo or at the top of first-run double bills but meeting with mixed response.25 During the week of August 21, Run of the Arrow reached its highest position in national box office, ranking thirteenth despite only fair reports from major exhibitors. Absent from Variety’s list of films grossing more than $1 million in 1957, Run of the Arrow in all likelihood did not break even.26 While the film received steady distribution, its expensive price tag set the box-office bar too high for a western lacking star power, thereby effectively ending Fuller’s access to million-dollar budgets as an independent producer.

After Fuller completed postproduction on Run of the Arrow, he made a financing and distribution deal that reteamed him with Twentieth Century–Fox and Robert Lippert. In the mid-1950s, Fox began increasingly to rely on independent producers for its product and to reconsider the value of low-budget filmmaking. With double bills continuing and location shooting leaving studio sound stages bare, Fox contracted with Lippert in August 1956 to supervise the production of seven black-and-white ’Scope pictures budgeted between $100,000 and $110,000 under the banner of Regal Films, Inc.27 Lippert’s first Regal title, Stagecoach to Fury (1956), made a healthy profit and demonstrated the potential of the low-budget film during an era dominated by multimillion-dollar extravaganzas. In January 1957, Fox extended Lippert’s contract for an additional sixteen pictures “with exploitation angles” budgeted between $125,000 and $250,000, including two by Fuller at the high end of the scale.28 Under the terms of the contract that applied to Fuller, the entire negative costs of the Regal films would be covered by loans from the Bank of America; the net receipts for each film would go half to Regal and half to Fox in perpetuity. The agreement also stipulated that Fox “may make such modifications, additions, or deletions in the picture[s] as it may deem necessary or desirable,” and required all films to adhere to the Production Code and receive an A or B rating by the Legion of Decency, a Catholic ratings organization.29 Finally, Fox reserved the right to approve story and cast and requested the films be shot on Fox studio property, using some studio equipment.30 The Regal agreement thus provided Fox with B pictures that filled the bottom half of double bills and made efficient use of studio resources, much like Bs during the studio era.

In 1957, Fuller produced two Globe films for Regal that were distributed through Fox: China Gate and Forty Guns; they were the most expensive films covered by the Regal-Fox agreement, falling into the programmer category. Under Globe’s production and distribution deal with Regal, Globe received a share of Regal’s percentage of a film’s net profits, less a $25,000 advance and any costs associated with profit participation or screenplay purchase.31 According to the agreement covering Forty Guns, for example, of the 50 percent share of the net profits owed to Regal, Globe received 80 percent of the first $100,000, 75 percent of the next $50,000, 70 percent of the next $50,000, etc.; for anything in excess of a million dollars in profits, Globe would receive a flat 50 percent of Regal’s net receipts. Out of Globe’s percentage of the profits also came repayment of the $25,000 advance, the $46,500 cost of purchasing the screenplay from Fox, and Barbara Stanwyck’s 2.5 percent profit participation.32 Fuller’s agreement with Regal and Fox provided him with complete financing, distribution, and a share of the profits, as well as access to Fox’s backlots and soundstages, equipment, and technical personnel. In exchange, Fuller agreed to lower budgets, major cast approval, and the potential for distributor meddling.

After directing A pictures with substantial production resources, Fuller returned to comparatively low-budget filmmaking with China Gate. A war adventure set in Vietnam but shot in black-and-white CinemaScope on Fox sound stages, China Gate went into production in January 1957 with a budget of $285,000, less than a third of the cost of Run of the Arrow.33 The cast included singing sensation Nat “King” Cole and two relative newcomers, Gene Barry and pre–Rio Bravo (1959) Angie Dickinson. China Gate finds Fuller revisiting the war genre with the story of a biracial woman who leads a group of French Foreign Legion soldiers to destroy a Communist ammunition dump in Vietnam. Drawing on narrative elements reminiscent of The Steel Helmet, Fuller continues his exploration of race and the promise of America while incorporating more tonal discontinuity than seen in Run of the Arrow. With stunning widescreen cinematography second only to House of Bamboo, China Gate illustrates the primary visual strategies adopted by Fuller as he transitioned back into low-budget filmmaking.

As in Hell and High Water and House of Bamboo, China Gate opens with expository narration designed to situate the film’s fictional action within historical fact. Stock footage sketches the rise of Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam and the threat produced by the Communist underground arsenal located in the northern region known as the China Gate. A hundred miles south lies a bombed-out village that “fights as it starves,” the home of our protagonist, Lea (Dickinson), and her young son. Half Caucasian and half Chinese, Lea runs a saloon and is friendly with both sides of the conflict; her son’s father, Brock (Barry), is out of the picture, an American soldier in the French Foreign Legion who married Lea but repudiated their child when he was born with Chinese features. Legion officers approach Lea to lead an expedition to the China Gate and blow up the ammunition dump that is fueling the Viet Minh’s efforts; her friendship with the Communist fighters and their leader, Major Cham (Lee Van Cleef), will help smooth the way. Lea accepts their offer in exchange for getting her son to America; the only catch is that her son-of-a-bitch husband is coming along, his disdain for her and their son balanced by the loving attention of Goldie (Cole), an African-American veteran of the Big Red One. The expedition group makes its way north, hiding under the cover of Lea’s cognac smuggling and dodging Viet Minh patrols and booby traps. At night, the men reveal their backstories, while Lea and Brock fight their continuing attraction and Brock his lingering racism. At the China Gate, Lea visits Cham, a former schoolteacher who was once her lover and now has his eye on the Viet Minh Politburo. Cham proposes to Lea and offers to take her child to Moscow for schooling; he takes her on a tour of the ammo dump to show her “why it is logical you should marry me.” Lea responds by shoving Cham off a balcony and revealing the location of the dump to the French expedition. Brock has a change of heart and tells Lea he wants them to be a family again, but when the expedition’s munitions fail, Lea sacrifices herself to set off the explosion. Brock, Goldie, and the dying French captain barely manage to escape, and the picture closes with Cole crooning the film’s melancholy theme song as Brock walks into the distance, holding hands with his young son.

Brock (Gene Barry, center) and Lea (Angie Dickinson, glancing over Brock’s shoulder) lead French Foreign Legionnaires through the Vietnamese jungle in a publicity still from China Gate. The love affair that rekindles between Lea and Brock is haunted by Brock’s racism. Author’s Collection

In its narrative structure and thematic development, China Gate is best viewed as an extension of The Steel Helmet and Run of the Arrow. As with The Steel Helmet, China Gate is the story of a military patrol on a mission, newly differentiated by its female protagonist, her personal motivation, and the relative newness of the Vietnam conflict to American fiction film. Both films are structured with alternating sequences of action and reflection, but in China Gate, rather than emphasizing what his characters learn through warfare—the harsh lessons of The Steel Helmet—Fuller focuses more on what characters learn through conversation—the paradox of America that carries over most directly from Run of the Arrow but was present even in The Steel Helmet. Fuller offers several images of America: the innate bigotry of Brock that is redeemed by love, the tough-yet-caring wisdom of Goldie, and Lea’s dream of a place where her child has a chance. As in his earlier pictures, Fuller suggests that America does not always live up to its ideals, but the fight for those ideals is what is most important. His pro-American stance becomes that much more explicit in China Gate through the contrast provided by Major Cham and the alternative life he offers Lea and her boy. As is true of the North Korean major in The Steel Helmet, Cham’s arguments are dictated by logic, but it is a logic that kills. Moscow’s gifts to the Vietnamese are bombs and death; by sacrificing herself to send her boy to America, Lea opts for the promise of life.

While Fuller’s attraction to irony runs continuously through his works, his use of unexpected contradictions to create dark humor reemerges in several lively instances in China Gate after being put on temporary hold during Run of the Arrow. These moments of dark humor occur at the dialogue level—as when, recalling lines from both Pickup on South Street and The Steel Helmet, a dying soldier tells his comrades, “Let there be a heaven, for it would kill me to have to come back here again”—and also on the level of plot and style. A vivid example occurs when a soldier entertains his fellow Foreign Legionnaires one night with stories from his life in France, acting out his old job as a traffic policeman. Nondiegetic sound effects of him stopping and starting the traffic add to the lighthearted tone of the scene. Just as the soldier happily explains that he stays in the Legion because “this is the way to live,” he is riddled with bullets by an unseen sniper. Upbeat comedy and joy quickly turn to surprise and horror. The soldier’s last words, already ironic due to his job—killing for survival—attain an additional layer of irony as they mark the moment of his death. By juxtaposing elements that sharply contrast in meaning or tone, Fuller’s scripts shock viewers in thrilling and often disturbing ways, prompting us to do a mental double take. Similar scenes that use contradictory dialogue and tonal contrasts for dark humor multiply in Fuller’s subsequent Globe releases.

The visual style of China Gate likewise expands upon Fuller’s previous work while anticipating the strategies that become dominant during his subsequent low-budget phase. After House of Bamboo, China Gate features Fuller’s most stunning use of CinemaScope. In scenes such as the introduction of Lea’s village, Brock’s visit to Lea at home, and Chan’s unveiling of the ammunition dump, Fuller and cinematographer Joseph Biroc skillfully arrange multiple points of interest across the frame in the foreground, midground, and background, using blocking, lighting, frontality, and movement to direct the viewer’s gaze and emphasize the emotional beats within the narrative. In their ability to visually summarize the conflict inherent in a scene, these shots recall the work of James Wong Howe on The Baron of Arizona and Joe MacDonald on Pickup on South Street and House of Bamboo. Also contributing to the emotional expressivity of scenes is editor Gene Fowler, Jr.’s insistence on squaring Fuller’s economical shooting practices with classical editing conventions. Fowler aggressively incorporates optical zooms and close-ups into Fuller’s long-take master shots throughout the film during moments of emotional significance, while constructing sequences featuring a limited number of camera setups in a manner that emphasizes the development and resolution of narrative action. These strategies explain the absence of the one-minute-plus long takes that slowed the narrative pace of Run of the Arrow, and they remain a part of Fuller’s aesthetic even after Fowler leaves his team.

Although China Gate was top-heavy with neither stars nor production values, its ninety-six-minute running time and the promotional push and strong first-run distribution orchestrated by Fox suggest that its producers and distributor intended it to be a breakout “in-betweener.” Fox provided the film with a $125,000 budget for a national publicity campaign—more than twice the ad budget for other Regal films—including a San Francisco premiere at the 4,700-seat Fox Theater, personal appearances by Gene Barry and Nat “King” Cole, and print, radio, and television ads.34 While the film opened “strong” in its premiere frame and played solo or at the top of the bill in prime houses in eighteen key cities throughout its month-long first run, box office was underwhelming and holdovers rare.35 An exhibitor report from China Gate’s opening-week booking in Minneapolis summarizes the consensus: “Nothing in cast names or too much otherwise to bring ’em in. Poor.” Reviews appear to have helped little, with favorable notices for the action scenes and central performances but widespread criticism of the contrived plotline and didactic, dialogue-heavy passages.36 By September, China Gate was screening in Buffalo at the bottom of the bill. While China Gate’s impressive cinematography, Vietnam setting, female protagonist, and blatant anti-Communism distinguished it from other action offerings, content alone was not enough to sell the film. Once again, China Gate demonstrated the difficulties of producing a successful programmer in the late 1950s.

Fuller’s follow-up, Forty Guns, was his most audacious assault on classical and generic conventions up to this point in his career, and its originality of conceit, freewheeling narrative, and sensational visual style anticipate the direction of his subsequent pictures. The film concerns a Wyatt Earp–like federal marshal who becomes personally and professionally entangled with a land baroness; both have younger siblings whose hijinks further complicate the relationship. The plot juggles several romances, grudges, behind-the-scenes corruption, and enough action to result in four murders, a suicide, and a serious maiming. At the core of the narrative is another of Fuller’s impossible conflicts: the marshal and the land baroness love each other, but the marshal has cracked down on the baroness’s empire and threatened the younger brother she has vowed to protect. Forty Guns was originally written during Fuller’s tenure at Fox, and Darryl Zanuck’s notes on the rejected script pinpoint some of the difficulties Fuller encountered when attempting to adapt his character and narrative interests to a studio western. The script’s larger-than-life female protagonist, criminal elements, multiple plotlines, and romantic rivalry threaten classical and genre conventions at every turn. Although in his autobiography Fuller describes his honest intention to dramatize America’s fascination with guns and violence,37 Forty Guns contains none of the didacticism of Run of the Arrow or China Gate. Instead, the film is loopy and visceral entertainment—astonishing, funny, and triumphantly Fuller.

Fuller first wrote Forty Guns as Woman with a Whip in 1953, his third original screenplay delivered to Twentieth Century–Fox as part of his option contract. Fox’s production head, Darryl Zanuck, wrote detailed notes on Fuller’s first-draft continuity but set aside the decision of whether or not to develop the script until Fuller completed his writing and directing assignment on Hell and High Water. Immediately after Hell and High Water wrapped production, Fox declined to purchase Woman with a Whip.38 Fuller began resurrecting the screenplay almost immediately after finishing shooting China Gate. Regal purchased the script rights from Fox for Globe, and Fuller convinced Barbara Stanwyck to star alongside Barry Sullivan. While Forty Guns was originally budgeted at $353,000, its production costs rose to $429,000 due to an increase in cast size and unforeseen expenses, making it by far the most expensive of the Regal-Fox pictures.39

Zanuck’s original notes suggest several reasons why Fox may have decided not to produce Woman with a Whip. The studio was in the middle of unrolling its first slate of CinemaScope pictures, and all of the films to be shot in 1953 had already been selected and their budgets assigned.40 In addition, Zanuck had problems swallowing the overall plot of Woman with a Whip, the multiple villains, and the characterization of Alamo, the land baroness. The original treatment Fuller provided Zanuck outlined a story about conflict between the legendary Earp brothers. Zanuck found this basic theme greatly diffused in the first-draft continuity, overshadowed by subplots involving Tombstone’s sheriff, Alamo’s crooked dealings and political power, and gratuitous violence. In particular, Zanuck considered the character of a “strong woman” who runs not only a big ranch but also a corrupt empire to be “phony,” an artificial construction that detracted from the realism of the Earp brothers and their “simple human problem[s].”41 He suggested eliminating the subplots involving Alamo’s financial and political empire and focusing instead on the problems Alamo and Earp have with their younger siblings and on the love stories between Wyatt Earp and Alamo and Morgan Earp and Louvenia:

This is real, honest-to-goodness stuff, and you can’t mix it with hidden dynasties and fabulous castles where thirty people dine at long, lace-covered tables.… I think you will be surprised to see the change that comes almost as a result of drastic elimination and supplying realism to replace contrivance.42

Rather than investing in substantial rewrites on a western property that did not fit well into Fox’s proposed slate of CinemaScope blockbusters, Zanuck reassigned Fuller to work on the script for Saber Tooth, a science fiction adventure story that originated with Philip Dunne. Zanuck’s notes on Woman with a Whip and his eventual rejection of the script highlight the importance of maintaining clarity and plausibility in scripts written for the major studios, as well as adhering to social norms and generic expectations. Multiple and diffused story lines, overly powerful women, and castles and caviar simply had no place in a Fox western; in a Globe Enterprises western, however, these unruly elements found a home.

A comparison of the March 1953 first-draft continuity script rejected by Twentieth Century–Fox and the February 1957 revised script produced by Globe reveals very few fundamental changes. The Globe script opens with federal marshal Griff Bonnell (Barry Sullivan) and his younger brothers Wes (Gene Barry) and Chico (Robert Dix) arriving in Tombstone to deliver a warrant for mail theft against Howard Swain (Chuck Roberson), a deputy sheriff under the employ of Jessica Drummond (Stanwyck), leather-wearing land baroness and “boss” of Cochise County. In town, Griff chats with his old friend John Chisum (Hank Worden), the local marshal who is going blind. While the Bonnell boys enjoy a scrub at Barney Cashman’s bathhouse, Brockie Drummond (John Ericson), Jessica’s unruly younger brother, challenges Chisum and kills him. Griff subsequently faces down Brockie with an imposing walk down Main Street, disarms him, and puts him in jail, though Jessica quickly rides into town with her forty guns and releases her brother. Jessica then takes away Brockie’s guns and scolds him for killing Chisum and getting a girl pregnant. Back in town, Wes, who acts as Griff’s second gun, gets friendly with Louvenia (Eve Brent), the daughter of the local gunsmith, and decides he’d “like to stay around long enough to clean her rifle.” Chico, the youngest Bonnell, resists his brothers’ decision to put him on a stagecoach for California, as he’d rather be a gunman than a farmer. Griff visits Jessica at her mansion to deliver the warrant for Howard Swain, and the two initiate a loaded flirtation; impressed by what she sees, Jessica offers Griff the job of local sheriff, currently held by Ned Logan (Dean Jagger). Logan, carrying an unrequited torch for Jessica, has Charlie Savage shoot Swain in jail to keep him from implicating Jessica in his crimes. When Jessica and Griff tour her property she reveals her past to him, again asking him to team up with her. After a suspiciously allegorical tornado nearly blows them away, Jessica and Griff enjoy a roll in the hay. Logan and Savage set up Griff to be killed in town, but Chico surprisingly saves his brother from the ambush. Logan just won’t give up, though, and sets upon Griff in Jessica’s house; Jessica pays off Logan and pledges her love to Griff, prompting Logan to hang himself. Wild man Brockie reenters the picture at Wes’s wedding to Louvenia, killing Wes minutes after the ceremony and driving a wedge between Jessica and Griff. Jessica pledges to stand beside her brother, though it means losing her empire; in the end, the judge and jury can’t be bought, and Brockie is sentenced to hang. Hearing the news from Jessica, Brockie grabs his sister and uses her as a shield to escape jail. Griff confronts them in the street and shoots through Jessica to Brockie, who falls with an incredulous “I’m killed!” Griff walks past the injured Jessica and intones, “Get a doctor. She’ll live.” Though Griff fears Jessica will never forgive him, the wounded woman runs after him on his way out of town, and the two drive off together.

When revising his Fox script for Globe, Fuller changed the names of the principal characters so they sounded less mythical and more naturalistic, making the Earp brothers the Bonnell brothers and renaming Alamo as Jessica Drummond. Fuller also apparently heeded Zanuck’s advice regarding the outsized characterization of the land baroness: rather than living in a castle guarded by Apache Indians, she now lives in a mansion protected by hired guns. One character is eliminated—Nellie, a hotel owner, whose lines are adopted by Barney the washtub operator—and two sequences are dropped: a scene in which Griff and Jessica walk off in search of water after the tornado has died down and are seen kissing in a stream by Griff’s brothers and a sequence in which Virgil/Chico wounds both Brockie and Griff in an attempt to avenge the murder of Morgan/Wes, his older brother. The first cut sequence would have added little new information to the narrative, while the second simply created another diversion from the final showdown between Griff and Brockie. Dialogue is also tightened in the revision, and additional double entendres increase the sexual humor. All in all, however, the revised script maintains the bulk of the plot structure and details Zanuck objected to four years prior. Fuller’s newfound independence provided him with the creative freedom to produce offbeat projects like Forty Guns that challenged the storytelling conventions embraced by the major studios.

Interestingly, the end of the plot, in which Brockie uses Jessica as a human shield, Griff shoots through Jessica to injure Brockie, and a healed Jessica runs after Griff, is exactly the same in the script rejected by Fox, the script produced by Globe, and in the completed film. In many interviews and in his autobiography, Fuller alleges that his original script ended with Griff walking away after killing Brockie and mortally wounding Jessica, but Fox insisted that the star of the picture survive to ride off with the hero into the sunset.43 If Fox executives did demand this change, they must have done so between Fuller’s submission of the treatment and the completion of the first-draft continuity, as the latter contains Griff’s same dismissive “She’ll live” as the film. It is curious, however, that Fuller did not revise the ending to fit his original vision when he rewrote the script for the Globe production. While it is possible that representatives of Fox, the Globe film’s distributor, again insisted on keeping Stanwyck’s character alive, the “happy” ending remains inexplicable and discordant with a story that builds toward a very unhappy—but typically Fullerian—resolution. Only the lyrics to the theme song that is playing at the end—“A woman with a whip is only a woman after all”—and a few stray lines of dialogue concerning the power of love and forgiveness provide glimmers of motivation for Jessica’s survival and reunion with Griff. On the other hand, Jessica’s death would have efficiently captured the impossibility of her love affair with Griff, as Griff’s decision to place his job and his loyalty to his brothers above his love for her would have resulted in her complete elimination. In its denial of an unequivocally positive resolution to the double plotline, such an ending would be more consistent with the majority of Fuller’s work. As it is, Jessica’s survival and sudden change of heart graft a classically tidy and triumphant ending onto a very untidy and problematic plot.

Indeed, the plot’s disregard for coherence and clarity in favor of maximum emotional punch is one of the most vivid examples of Fuller’s aesthetic at work, and well illustrates his melodramatic sensibility. Some plot developments, such as the pregnancy of Brockie’s girlfriend, arise and vanish immediately, never to be mentioned again, while others, such as Jessica losing her empire, are referenced but not fully explained. At least two plotlines—the Bonnell sibling conflict and the romance between Wes and Louvenia—come to a premature and abrupt end, while two others—the Drummond sibling conflict and the romance between Griff and Jessica—involve dramatic character reversals in the third act. The lack of tight causal construction in Forty Guns prompted critics to complain that the film was “unnecessarily confusing,” with a “cluttered” plot that “explodes rather than develops.”44 While it might seem haphazard on the surface, much of the narrative development in Forty Guns functions to intensify steadily the pressure on Jessica and Griff’s relationship. The causal factors leading to the seemingly impossible conflict between the two are quite clear: Jessica and Griff love each other but are also protective of their siblings. When Jessica’s brother kills Griff’s brother, Griff must bring him in to be hanged, but Jessica swears, “I’ll do everything I can to see him live.” The sibling and corruption plotlines both enable Griff and Jessica’s romance to blossom and create a series of obstacles to their successful union. Genre conventions aid in providing narrative motivation for random plot developments, while each additional obstacle builds toward a showdown between Griff and Jessica that cannot be resolved in a mutually beneficial way. The sudden, often audacious twists and turns in the narrative repeatedly raise the stakes for the protagonists, producing the plot “explosions” denigrated by the critics but embraced by Fuller.

Just as Fuller abandons the coherence of classical narrative conventions in an effort to heighten the impact of the central conflict, he also plays fast and loose with the western genre to produce humorous and shocking thrills. The most overt example of his generic play is the script’s uproarious use of analogies linking sex and western iconography. Jessica berates Brockie for beating his pregnant girlfriend with, “If you can’t handle a horse without spurs you’ve no business riding,” while she later tells Griff about a cabin, “I was bit by a rattler in there when I was fifteen.” He replies dryly, “Bet that rattler died.” Louvenia’s job as a gunsmith is an easy source for sexual humor, as when Wes tells his brothers about her: “She’s built like a 40/40,” and she asks him after they kiss, “Any recoil?” An even more explicit exchange occurs after Jessica asks Griff to be sheriff: “I’m not interested in you, Mr. Bonnell. It’s your trademark. Can I feel it?” When she reaches out her hand for his gun, Griff replies, “Uh-uh. It might go off in your face.” These verbal conflations of animals, guns, and sex take some of the underlying metaphors found in westerns and exaggerate them for comic effect, involving the viewer in a knowing wink at a convention of the genre. This use of dialogue is distinctly different from references to Chico as a “wetnose” or Brockie as a “calf” who needs to be “broken.” The latter usage functions as a sort of western patois, the equivalent of a pickpocket being called a “cannon” in Pickup on South Street. Fuller’s dialogue increasingly contains colorful analogies and absurd references as his Globe career progresses, imbuing his films with additional self-consciousness. The outrageousness of the dialogue provides campy comic relief from narrative situations designed for maximum tension.

Fuller’s play with generic elements in Forty Guns extends beyond the narrative and into the realm of the visual, transforming three western conventions—the showdown, the wedding, and the funeral—into highly stylized sequences. The initial confrontation between Griff and Brockie after the killing of Chisum primes the viewer to anticipate a classic shootout: Brockie is standing in the middle of the town’s Main Street, wildly waving his gun and yelling, while Griff approaches from the opposite end of the street, covered by Wes and his shotgun. The typical western script would have Griff stop fifty yards or so away from Brockie, say a few words, and pull out his gun. Instead, Griff simply keeps striding toward Brockie, each step punctuated by increasingly loud musical chords. Dun, dun! Dun, dun! As the music continues, the long shot of Griff’s walk is broken down into repeating tight shots of his face, his legs, and his shifting point of view of Brockie. Here Fuller reduces the showdown to its most basic elements: Griff’s calm determination, his destination, and the feet that will take him there. As Griff and Brockie are not shown in the same shot until the end of the sequence, the actual space between the two is abstracted, and the viewer is not quite sure when Griff will reach his target. Suddenly, Fuller varies the initial pattern he established: an extreme close-up appears of Griff’s eyes, shifting up and down to reflect his movement, intercut with gradually tighter point-of-view shots of Brockie. This cut never fails to elicit gasps when Forty Guns is projected in a theater—imagine, eyes bigger than your body bobbing up and down on the gigantic CinemaScope screen! This is the boldness of Fuller. The repetition of images in this sequence builds tension and suspense, while the unnatural size of Griff’s eyes in the CinemaScope frame, the extreme changes in shot scale, and the musical score contribute an element of hysteria.

Typically, strength and skill are illustrated in a showdown by who draws first and shoots most accurately; it is the bullets that close the distance between the two opponents and mark one as triumphant and the other as unworthy. In the showdown at the beginning of Forty Guns, however, Griff himself traverses the street and attacks Brockie, his mastery over all others demonstrated by his eyes, his walk, and his ability to transfix and dominate his opponent even when unarmed. The walk reimagines the standard western shootout, providing significant characterization of Griff in an unusually intensified and startling fashion. When Griff again faces Brockie on Main Street at the end of the film and decides to shoot through the woman he loves in order to kill the man he hates (another deromanticized break from genre tradition), his actions thereby appear entirely in character; the walk has already presented Griff as a man of great confidence and control who is capable of anything.

Frame enlargements of Griff Bonnell’s (Barry Sullivan’s) walk down Main Street to subdue Brockie Drummond (John Ericson) in Forty Guns. Rhythmic editing between the images, punctuated by the percussive score and the sudden changes in shot scale, injects tension into Fuller’s reimagination of the classic western showdown.

Fuller’s presentation of Wes and Louvenia’s wedding is equally daring, as he turns the communal celebration of the couple’s nuptials into the prologue of a funeral. The wedding itself is never seen; instead, the scene begins with an extreme high angle of the crowd outside the church, waiting for the couple and their family and friends to emerge for photos. The moment is joyous, with the playful, upbeat score from the previous washtub scene (Fuller loves those washtubs!) carrying over into “Here Comes the Bride.” As Louvenia, Wes, and their families, beaming, pose in a medium close-up for a picture, Wes asks his brother, “Aren’t you going to kiss the bride, Griff?” The music lulls to a stop, Griff leans past his brother to kiss Louvenia, and a gunshot is heard. Whoa! The viewer is as startled as the characters. After an insert of Brockie on his horse, gun in hand, two over-the-shoulder close-ups favoring first Wes and then Louvenia are intercut at an increasing rate, following the groom as he collapses into his bride’s arms and onto the ground. The rapid, repeating close-ups extend the duration of Wes’s fall, heightening the impact of the murder. The scene’s euphoria has turned to shock and despair. In a wide shot the crowd converges around the prone couple, and Louvenia’s gasping wails are heard like the cry of a wounded animal: “Wes! Wes!” A high-angle close-up looks down on the bride, struggling on the ground under the weight of her dead husband’s body. It is all too unnerving. Wes and Louvenia, the high-spirited, double-entendre-trading couple, were married for all of thirty-two seconds—one of the most extreme tonal shifts in all of Fuller’s work.

A slow dissolve then segues into Wes’s funeral, as visually stylized and abstracted as the showdown and the wedding. Typically, western funerals emphasize communal mourning and the vulnerability of settlers on the untamed frontier. In Forty Guns, Fuller leeches all sentimentality from the ritual until only its iconography remains. In the first shot, Louvenia stands on a hilltop in widow’s weeds, and the camera tracks left past a hearse and in on Barney, singing “God Has His Arms Around Me.” Following a brief cut in to a close-up of Barney, the third shot of the sequence reverses the first, tracking back out and to the right, past the hearse and settling again on Louvenia. The three-shot scene reduces the funeral to its barest elements: the widow, the dead man, and the act of mourning. The slow pace of the sequence, its camera movement, and lack of cutting contrast with the end of the previous scene, in which rapidly cut, static close-ups of Wes falling on top of his new bride heighten the horror of his murder. Together, the wedding and funeral compress the married life of Wes and Louvenia into only a little over three minutes of screen time, serving as one of the most expressive examples of how Fuller’s films exploit stark contrasts in tone and action in a jarring, ironic, and often unsentimental fashion. While Run of the Arrow respectfully acknowledged the tropes of the cavalry-and-Indian western while attempting to expand their application through a unified, coherent narrative, Forty Guns picks key generic situations, stands them in a row, and gleefully blows them up.

Despite its narrative pleasures and formal inventiveness, Forty Guns received less promotional fanfare and a more tentative first-run release than its predecessor and struggled at the box office. The picture opened in September 1957 at the Fox Theater in Detroit on the bottom half of a double bill with Twentieth Century–Fox’s Sea Wife (1957), though in subsequent weeks it headlined in other venues, often paired with another Regal picture.45 Reviews for the film were generally positive, finding the fast-paced action and pairing of Barbara Stanwyck and Barry Sullivan particularly ideal for the drive-in market.46 Fox’s decision to book Forty Guns on the bottom half of the bill in the largest major-market first-run houses, as well as only in secondary runs in New York City, reveals the distributor’s lack of faith in the film as an A-grade contender. As critics suggested, the film was well suited for drive-ins, yet cost too much to make a profit without a successful first run as a headliner. Reaching as high as number twelve only once on the weekly box-office list, Forty Guns proved to be another in-betweener that could only make it as a B.47 While an August 1957 memo from Fox suggests that the studio was considering an agreement for Fuller and Regal to produce two additional action pictures at a cost of $300,000 each, after the lackluster showings of China Gate and Forty Guns this proposal never came to fruition.48 Following Forty Guns, Fuller ended his associations with Lippert and Twentieth Century–Fox and further lowered his budgets for subsequent Globe pictures.

Fuller retrenched in 1958 by producing a true B movie, Verboten!, with financing from RKO.49 By this time, RKO had turned over its handling of prints, billing, and other administrative work to the J. Arthur Rank Association and unveiled a plan to make the studio a key source of financing for independent producers. According to the plan, RKO would provide financial support on either a short-term or long-term basis, with no restrictions on cast or distributor and no unloading of studio charges or other overhead.50 Verboten!, the story of a GI in Germany who falls in love with a local woman and subsequently works for the American military government after WWII, features no stars and little production value. Fuller shot the film entirely in Los Angeles during approximately two weeks, and intercut his footage with stock images of artillery and aerial warfare, Nazi atrocities, and postwar Germany to increase the realism.51 Efficiently staged and sensationally presented, Verboten! is, like Park Row, a product of Fuller’s passions. What it lacks in polish it makes up for in strength of purpose.

The film begins in Germany during the last days of World War II. Sergeant David Brent (James Best), part of a U.S. Army patrol weeding out snipers in the remains of a bombed-out town, is wounded and taken in by Helga Schiller (Susan Cummings), a German who protects him from retreating soldiers. Helga nurses Brent back to health, arguing that she will show him “the difference between a German and a Nazi,” and he in turn protects her and her family when U.S. forces occupy the town. Brent falls in love with Helga, and when the war is over he arranges to stay behind in Germany as a civilian, work for the American military government, and marry Helga. Meanwhile, Helga’s neighbor, Bruno (Tom Pittman), arrives back in town, disillusioned by the German surrender but still faithful to the Nazi party line. Helga tells Bruno she views her new husband as a “meal ticket,” a good source of otherwise scarce food, clothes, and nylons. Bruno becomes a leader of the Werewolves, underground remnants of the Hitler Youth intent on disrupting the American occupation, and induces Helga’s younger brother, Franz (Harold Daye), to join. Bruno uses his job at the U.S. Army headquarters to provide intelligence to the Werewolves and manages to get Brent fired as the result of a Werewolves-organized food riot. Brent confronts Helga after Bruno reveals to him her motives for marriage, and though Helga swears she now loves him, Brent fails to believe her. Helga discovers Franz is a member of the Werewolves, and in an effort to redeem them both, takes him to the Nuremberg trials to confront the Nazi legacy. Shocked by what he sees, Franz helps bring a fiery end to the Werewolves, while Brent recognizes Helga’s true love and the two reunite.

Though at times the integration of its disparate elements threatens to come apart at the seams, the emotional effect of Verboten! builds as it goes along. The film contains both a subjective tale of moral transformation and an objective rendering of Germany after WWII, a love story and historical intrigue, a fictional film and documentary footage—all interwoven with a single goal: to inform and arouse the viewer. Working again with cinematographer Joseph Biroc, Fuller constructs his scenes with the utmost economy, consistently relying on camera movement to redirect attention and create new compositions within long-take master shots; shots lasting two to five minutes are not uncommon amongst the original footage. The end result can be a bit stagy, and as these sequences primarily depict the romance, viewers are more likely to feel they are witnessing the love affair than becoming emotionally invested in it. With the arrival of Bruno and the shift in the narrative toward the Werewolves subplot, however, the use of stock footage increases and the pace quickens. Brent, previously the site of viewer alignment, recedes into the shadows while Franz emerges at the center of the story, his close-up reaction shots hinting at his significance. The consistent use of stock footage throughout the film primes the viewer for the impact of the Nuremberg trail scene. Lacking the resources to fully depict the world of the story, Fuller cunningly integrates stock footage and his own fictional footage within the same scenes, using eyeline matches and other devices to suggest the images are all from a unified space and time. The result can be disorienting, as differences in the content, quality, and texture of the footage call attention to themselves. Rather than highlighting the narrative’s lack of verisimilitude, however, the documentary nature of the stock footage influences our understanding of the rest of the film, consistently suggesting parallels between the real world and the fictional world that lend credibility to the narrative. In the Nuremberg trial scene, stock footage not only fills in the blanks of the story world (images of the courtroom, the judges, the defendants, etc.), but also presents a film within the film: footage from the actual trial seen within the story by Franz, footage that becomes the source of his character transformation.

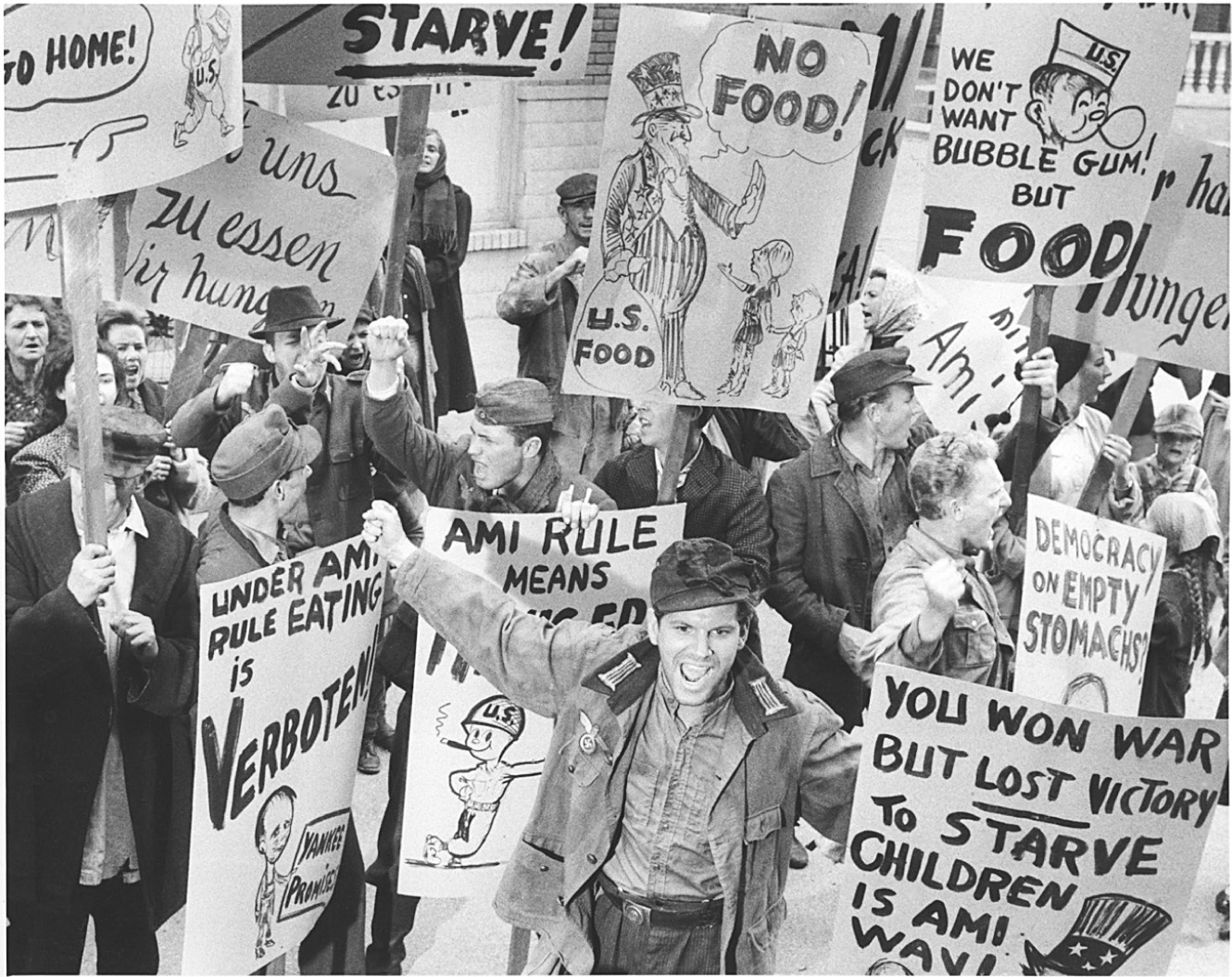

Eric (Sasha Harden, lower center), a young neo-Nazi “Werewolf” in post–World War II Germany, leads a food riot to disrupt the American occupation in a publicity still from Verboten! Fuller, who occasionally worked as a cartoonist in his youth, did the drawings and lettering on the English-language posters. Author’s Collection

Verboten!, like Fuller’s other cinematic explorations of identity, nationalism, and the struggle for survival, testifies to his optimistic belief that “with film, we can make progress and history and civilization.”52 During the Nuremberg sequence, we see the transformative power of film in action. Fuller opens the scene with original footage of Helga, Franz, and others filing into courtroom pews intercut with documentary footage of the arrival of the actual trial’s judges, prosecutors, and defendants, suggesting that both are inhabiting the same space. Initially, voice-over narration read by Fuller assumes the role of a court commentator, setting the stage for the events of the trial. The camera tracks in to frame Helga and Franz in the last row, and cuts back and forth between the siblings and a frontal close-up of Franz, still skeptical of the proceedings. Now assuming the voice of the American lead prosecutor, Fuller’s voice-over narration announces, “We will show you the defendants’ own film. You will see their own conduct” over a stock shot from the rear of the Nuremberg courtroom—as if from the point of view of Franz and Helga—of a man at a lectern in front of a blank projection screen.

The voice-over then narrates what the siblings are presumably seeing onscreen, the film within the film: a history of Nazi atrocities, beginning with those against fellow Germans and ending with the Final Solution. As the narration repeats the Nazi party propaganda that led to the incidents onscreen, the scene cuts back three times to a close-up of Franz superimposed over flashbacks to Bruno’s Werewolf rhetoric, suggesting that Franz is connecting the past to the present and cueing us, the viewers, to do the same. As the documentary footage becomes increasingly graphic, the pace quickens and the inserts of Franz’s close-up are more frequent. The close-ups and point-of-view editing structure align us with Franz’s viewing experience: we see what he sees as he sees it, and we see the effect it has on him. After horrific images of gas chambers and piles of skeletal bodies, the narration culminates with the declaration “This was genocide” over a final shot of a corpse being unceremoniously tossed into a pit; Franz breaks down next to his sister, sobbing, but she turns his face toward the screen: “You’ve got to look. We’ll look together. Everyone should see.” This is Fuller, prodding us: we have to face the past in order to affect the future. In encouraging Franz to watch the Nuremberg footage, Helga opens his eyes to activities he had indirectly fostered but had long denied. After watching the film, the boy recognizes his own complicity and guilt. He runs to Brent, crying, “I saw film. I didn’t know! I didn’t know,” and promptly confesses his association with the Werewolves. The process of viewing the footage implicates Franz, the viewer made manifest in the film, and forces him—and by extension us—to fully confront the horror of the Nazi crimes. This is what Verboten! has been working up to: an honest depiction of the past, of a moral transformation, and of the need to take responsibility and enact change. The sequence is gut-wrenching and powerful. For Fuller, learning the truth is essential, and cinema has a role to play.

Although critics reacted well to the film’s sense of conviction, Verboten! received only spotty promotion and distribution, the most uneven of any Fuller picture from this era. Verboten! was the last film made before RKO’s collapse, and the studio had ceased operating by the time it was completed. Rank initially took over distribution for RKO, and in March 1959 booked Verboten! into the Palace in Milwaukee and the Fox in Detroit, where it held on for two weeks. Rank dropped out of U.S. distribution later that month, and Columbia picked up Verboten! as part of its four-picture deal with Fuller.53 When the film finally returned to theaters in the second half of 1959, it appeared largely in secondary run and on the bottom half of first-run double bills. Playing in only eight major cities in first run, Verboten! did not open in New York until July the following year.54 Most reviews found Verboten!’s theme and use of documentary footage both authentically gripping and exploitable. In the New York Times, Eugene Archer gave the film an uncharacteristically strong notice for a low-budget picture, describing it as “intriguing evidence that the offbeat and interesting American “B” picture, often considered a thing of the past, has not quite disappeared from the screen.”55 But, with its spotty distribution, positive reviews could do little to help Verboten! generate box office. Nevertheless, Fuller continued to formulate ambitious plans in 1958.

After finishing Verboten!, Fuller moved into preproduction on The Big Red One, a story about his old infantry outfit that he had been developing since World War II. He announced in Variety that he had secured a contract with Bantam for a novelization of the film, had the cooperation of the Defense Department, and was seeking permission to shoot in Czechoslovakia.56 Warner Bros. was backing the project, an unsurprising move given that Fuller had written a scenario and a screenplay for the studio earlier in the decade.57 At the same time, Fuller also revealed in Variety that he was looking for a financing-distribution deal to enlarge Globe into a six-films-a-year production unit, plus television work, though he did not intend to produce and direct every film.58 Although none of these plans materialized, Fuller did shoot Dogface, a pilot for CBS, under the Globe TV Enterprises banner in March 1959. Fuller produced, wrote, and directed the half-hour pilot about American GIs in World War II and shot it on Columbia’s ranch in the San Fernando Valley. A month later, Variety reported that Globe would develop a second series for CBS, a western entitled Trigger-happy, although it is unclear whether or not Fuller actually advanced these plans. As with over 80 percent of pilots shot for television during the period, neither Fuller project was picked up, likely resulting in the loss of hundreds of thousands of production dollars for Globe.59

Fuller’s attempt to enter television was a logical outgrowth of his low-budget film production, given the similarities in budgeting, casting, scheduling, and content between very low-budget films and television shows. Television was commonly viewed in the industry as the last refuge of the B films that were being squeezed out of movie theaters and, if picked up by CBS, Fuller’s pilots would have provided him with a hedge against the shrinking market for his brand of low-budget action film. Yet Fuller’s long-take visual style and nontraditional narrative interests left him ill-suited for the intimacy and family orientation of broadcast television. While he would find work directing for TV during the 1960s, Fuller’s chances to produce his own series ended in 1959.

Sensational Style: The Crimson Kimono and Underworld, U.S.A.

After The Big Red One was put on hold by Warner Bros. in late 1958, Fuller signed a four-picture distribution deal with Columbia Pictures.60 Earlier that March, Columbia had moved to a new, indie-friendly format after failing to find a production chief following the death of Harry Cohn. Variety reported Columbia’s interest in financing and distributing packages brought in by outside producers, acquiring properties to attract top talent for profit-participation deals, and offering staff producers the chance to set up independent companies on the lot. By the end of the year, Columbia had more contracts with independent producers than any other major studio, including deals with producer-directors such as Otto Preminger, Stanley Donen, and William Castle.61 Contractual arrangements with independent producers varied; the producer could utilize Columbia facilities and personnel or receive a minimum of direct help during production.62 At the same time as it sought new, independent blood, the studio switched from an emphasis on programmers to a reliance on blockbusters, citing a trend against smaller pictures, especially overseas. The low-budget action picture had been a staple of Columbia’s production slate, but now the studio suggested it would only carry low-budget films that could be exploited for top, stand-alone dates both domestically and abroad.63

Although little definitive information exists regarding the budgets and shooting schedules of Fuller’s two Columbia pictures, The Crimson Kimono and Underworld, U.S.A., it seems probable that they were completed for $1 million or less after shooting for a month or under based on reports in Variety, cast lists, number of sets, and use of locations. Compared to other contemporary Columbia releases such as the $3.5 million Song Without End (1960), Suddenly, Last Summer (1959), Anatomy of a Murder (1959), and A Raisin in the Sun (1961), Fuller’s pictures do not appear to be the blockbusters the studio was trumpeting in the trades.64 Instead, Fuller’s two releases seem again to fall into the “in-betweener” category, designed to headline on a budget. Written to revitalize their given genres through the incorporation of sensational subject matter, The Crimson Kimono and Underworld, U.S.A. find Fuller more consistently utilizing constructive editing and indirect representation to vividly present hard-hitting action and violence.