WHAT PATTABHI JOIS described while touching his heart and speaking of “the enemies of the heart” was a description of the basic symptoms of suffering. “Saṁsāra hālāhala,” we often chant before we begin an āsana class. Hālāhala refers to the poisonous herb of saṁsāra (conditioned existence) that keeps the wheel of suffering in motion. It’s said in this chant that we have swallowed the poisonous herb of habitual existence, and the path of yoga is using the poison as a means of finding our way back to complete sanity. But more important than his description of the symptoms of distress was Pattabhi Jois’s later remark about how to work with those symptoms. His reference to the five kleṣas is derived from the Yoga-Sutra attributed to Patañjali. After describing duḥkha as a product of repetitive psychological and physical patterns, Patañjali describes the five factors that contribute to putting into motion the wheel of suffering. The five kleṣas are as follows: avidyā (not seeing things as they are), raga (attachment), dveṣa (aversion), asmitā (the story of I, me, and mine), and abhiniveśa (the thirst for further existence).

One of the interesting aspects of considering the six poisons as symptoms of the five kleṣas lies in understanding what we mean by a “symptom.” A symptom, by definition, is a characteristic or sign of the existence of something else. The term symptom comes from sym, “together,” and tom, “part, piece, or slice.” A symptom, like any one of the six poisons—desire, anger, delusion, greed, envy, and sloth—is only a slice of what is actually occurring for someone; on a deeper level we need to look at the root causes of suffering.

The five kleṣas keep suffering in motion because they create loops in the mind-body that reinforce habitual patterns of perception and reaction. They are a concise summation of the basic psychological principles of yoga. The term kleṣa comes from the verbal root klis, which means “to suffer, torment, or distress.”

Let’s explore the ways in which these five kleṣas create and reinforce patterns of habit. Perception begins in the sense organs. One cannot perceive the world independent of the sense organs and the mind. All experience is filtered through the sense organs and the mind, and as data comes in through the sense organs, it becomes organized into experience. The term psychology, in the context of yoga, can be defined as “the organization of experience,” or, more specifically, the way the sense organs and mind organize sense data into subjective experience.

As data moves through the sense organs, we become aware of experience through sensations. We know that there is sensation because there is always a corresponding feeling. Slowing down our experience allows us to notice the ways in which we organize experience. On close inspection, which is what we call “mindfulness,” we notice how all sensations give rise to feeling. Feelings can be positive, negative, or neutral. They can be pleasurable or unpleasurable. It’s almost as if all sensations in the body fall into one of three buckets: positive, negative, and neutral. For instance, if we are sitting in meditation and feel pain in the knee, we are aware of pain in the knee because we are feeling sensations. In other words, feeling is a mind-body process.

When we feel feelings that are negative, such as pain in the knee, there is usually a corresponding reaction of either attachment (raga) or aversion (dveṣa). Attachment is the desire to repeat pleasurable experience, and aversion is the act of trying to get out of uncomfortable feeling. One can sum up both attachment and aversion under the umbrella term clinging, because when you look deeply into attachment, you find aversion to what is not pleasurable. Attachment is aversion to displeasure, and aversion is attachment to pleasure. Aversion is clinging to what is pleasurable. Attachment is the leaning into experience, and aversion is the leaning away from experience. Most of our psychological and physical energy is spent flip-flopping back and forth, moment to moment, between attachment and aversion.

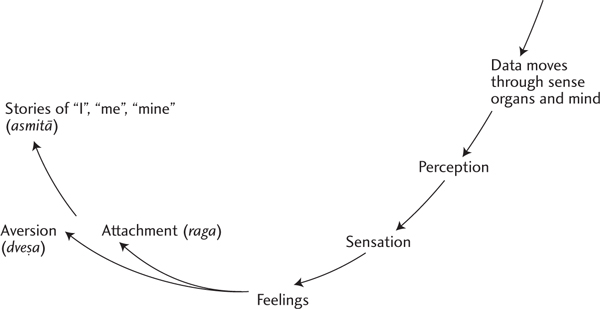

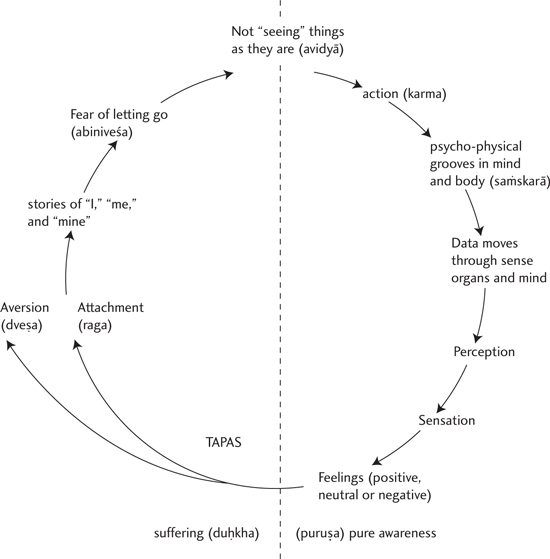

Yoga is the practice of going beyond our habits of creating opposites. When we can remove the deeply ingrained habits of our likes and dislikes by seeing not only how they cause separation but also how we construct and act out these habits, we arrive in a reality prior to separation. Attachment and aversion are always happening to a “me” outside of experience (see diagram 1).

Diagram 1

Whenever there is attachment or aversion, there is always the creation of a story of self. This is called “asmitā.” For example, if there is pain in the knee, it is experienced as a physical phenomenon, namely a negative feeling, until the moment that there is aversion to the pain. When the aversion to feeling sensation begins, there is a mechanism in the mind that creates a sense of “I” and superimposes this “I” on the unfolding physical experience. There is a movement from feeling pain in the knee to articulating to ourselves pain in the knee as something happening to “me.” We say to ourselves, “There is pain in my knee,” “I don’t like this.” In this instinctual moment, an “I” is born that has inserted itself into the phenomenon of pain, but was not initially built into the sensation. In other words, the feeling of pain in “my” knee is an addition to what is unfolding. This is the beginning of duality, because through aversion, a sense of self is created that separates the experience from the one who is experiencing.

Asmitā, the experience of an “I, me, and mine” comes from a mechanism in the mind called the ahaṇkāra. This word comes from the verbal root kr, meaning “action” or “to make,” and aham, which means “I.” It is best translated as the “’I’-maker,” and can be thought of as a mechanism in the mind that creates a story of self that is constructed on top of any phenomenon of feeling occurring moment to moment.

Asmitā, the “I”-maker, as a mechanism that gives rise to the feeling of “I, me, and mine” can, for practical purposes, be conceived of as a storyteller. When you contemplate your own thinking process, you may come to notice that almost all of your thoughts are stories about you! Most of us go through the day telling ourselves endless stories about ourselves. Our perception in daily life seems to pivot around this ongoing narrative of “me.” We talk to others about ourselves, and if there is no one around, we talk to ourselves about ourselves and call it thinking!

Many scholars translate ahaṇkāra as “the ego.” However, Freud’s definition of the ego is that which mediates between conscious and unconscious, internal and external, personal and social, and is considered, in his theory, to be the center of the personality. In yoga psychology, the “I”-maker is a cause of suffering (kleṣa), because it is constantly filtering our experience in a self-centered way. This takes Freud’s idea of narcissism much farther. It’s not so much that we have fallen for our image of ourselves; rather we are constantly overlaying each moment with a story of self, preventing a direct experience of reality, creating a case of mistaken identity! Furthermore, compassion, listening, or the ability to take in others is always superseded by the aggressive mechanism of the “I”-maker.

Down the road from my house at a local photocopy shop there is on a table with staplers and pens an enormous elastic-band ball—green and blue and red and very dense. When you take one band, wrap it around another, over which you wrap another band, and so on, after a while the ball grows larger and tighter. The personality is like an elastic-band ball: the wider the diameter, the more dense the core. Our stories of ourselves wrap one over another, creating conceptions of self that we fail to see as conceptions. Instead, we think of ourselves not as stories wrapped around other stories, but as fixed and somewhat permanent entities. As we age, the stories we tell about ourselves, much like the elastics on the circumference of a ball, have to be stretched wider and longer in order to wrap around our previous conceptions of self. If we imagine the self as an elastic-band ball that is getting larger, we can see how the more we create stories of self, the more the core of the self feels real. The center of an elastic-band ball is under great pressure. It is tightly wound and feels more like structure than elastic process. The stories of the self give us the impression that the self actually exists, but at bottom, it’s simply an unstable cognition. The imagination uses the raw material of life to create narrative structures that serve to further entrench our belief in a solid and stable entity called “me.”

The next kleṣa is abhiniveśa, which is most often understood as the fear of death. However, when you contemplate death, and the corresponding fear that arises whenever you think about death, you begin to see that what you fear most is not that your body is going to decompose or that your hair is going to burn up in flames, it’s that “I” am going to die. This story of “me,” this anthology of “I,” comes to an end. Whether you believe in a future life or not, these chapters of “I” that you’ve been writing from moment to moment and that you’re most thoroughly invested in will come to an end. Since you can’t know for certain what happens at the threshold of death (or even in the next moment, for that matter), the mechanism of the “I”-maker begins to speculate, out of existential fear, since it knows not what will occur beyond that door. Even when you feel lonely and alone, who is actually alone?

Abhiniveśa is not the fear of the death of the body per se, but the fear of letting go of the story of “me.” The purpose of meditation is to watch the process of clinging and thus gain insight into impermanence, which has, as an effect, psychological stillness. The very same phenomena that dominate our lives and actions when we’re unaware of them are seen to be impermanent and insubstantial in the light of awareness. Abhiniveśa cuts to the heart of our attempts at permanence. At the moment of death, we can no longer hold on to our conceptions of self. Palliative-care workers describe, time and time again, the difficult process of dying for someone who clings incessantly to their ideas of themselves, others, or life in general.

Why wait until the moment of death to let go of these constructions of self when we can do so in every moment? Paradoxically, we hold on because we see that these stories of “I, me, and mine” keep us at a safe and conceptual distance from reality, which gives us the illusion of comfort, existential security, and permanence. This illusion is called avidyā. The Sanskrit vidyā, as described before, becomes the Latin word vidéo, which in English becomes the word video, meaning “to see.” The prefix a turns any word in Sanskrit into its opposite. Avidyā, therefore, refers to the inability to see things or be with things as they are. Avidyā describes not being engaged with life as it unfolds and passes away. Why can’t we be present with life? We can’t see things as they are (vidyā) because of our habitual patterns of attachment and aversion. This is an amazing and troubling aspect of our human condition. We already exist as people in the here and now, yet we still try to construct ourselves as “selves” in the present moment, and find ourselves missing the present moment completely.

There is a joke in yoga that asks, “If you had to hide something that was the most valuable thing you had, where would you hide it?” The answer is: “in the present moment.” If you hide something in the present moment, no one will be able to find it. Most of the time we are not present or engaged with things as they are (vidyā), because we are so caught in deep grooves of raga (attachment), dveṣa (aversion), and our stories of self (asmitā).

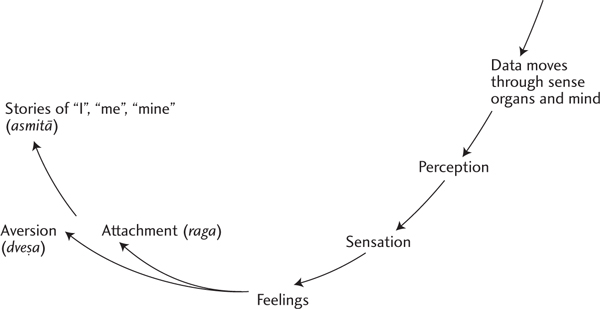

Since we take actions (karma) based on these habituated patterns of attachment and aversion, we reinforce in the mind and body those same patterns. The effects of our actions leave residues in the mind-body. These residues are called saṁskāras. Saṁskāras are the psychological and physical grooves that influence the way we perceive each moment of experience based on previous actions. The saṁskāras groove and condition our organs of perception. Therefore, the actions that we take, and their particular consequences, create in the mind and body predispositions to perceive and act in each moment in habitual and conditioned ways (as illustrated in diagram 2). This completes the cycle of saṁsāra, illustrating the turning wheel of suffering.

What is important to remember is that while this cycle is descriptive of a state of dissatisfaction, it is a cycle open to change. The underlying structure of the brain and the basic substratum of the body itself are both changing all the time. Always in motion, the brain and body are structurally unstable, which accounts for the flexibility and elasticity of our human organism. Not only do our conditions change, our conditioning can change as well.

To illustrate the way the basic patterns of mind and body (saṁskāras) change, imagine the film of a camera. Imagine that the film represents your mind, brain, and body. Now imagine using the camera to take a picture of a tree. When a picture is taken, the film is exposed to new information—that of the image of a tree. In order for the image to be retained, the film must react to the light and “change” to record the image of the tree. Similarly, in order for new patterns of behavior and action to be retained in memory, changes in the mind-body representing the new knowledge must occur.

Diagram 2

Looking back at diagram 2, we see that not only is this a description of suffering, it is also descriptive of the psychology of addiction, because the mind-body circulates the same patterns through repetition, reinforcing repetitive choices and actions. While presenting this model to a group of psychiatrists at a conference on mind and body, one doctor described this as “cognitive behavioral therapy on steroids!” This model describes not only our addiction to that which on the surface causes us distress or discontent—such as habits of smoking, drugs, gambling, or sex—but, on a more subtle and profound level, articulates our addiction to creating stories of self. At the core of any addiction lies the addiction to a story.

Yoga psychology pushes us to see through the addictive tendency to create stories of ourselves by representing ourselves to ourselves in order to make us feel real. But this reality is an illusion. The self is nothing more than a conglomeration of stories stretched out and overlapping one another like the giant elastic-band ball. Let’s use an example.

Suppose we are at home alone and after finishing household chores, making a meal, checking e-mail, and engaging in other distractions, we begin to feel lonely. Perhaps this loneliness is accompanied by a feeling of boredom and then sadness. This is not an uncommon experience. As the feelings of loneliness and sadness fill our awareness, the tendency in the mind is to look for a way out of these negative feelings. Instead of allowing these feelings to arise, we turn to the freezer, take out a pint of ice cream, and finish the pint faster than we realize. (You can substitute in this example whatever your common avoidance strategy is.)

After finishing the ice cream in a state of numbness and dissociation, we begin to feel a threefold feeling. Firstly, we feel physically terrible for having eating an entire pint of ice cream. Second, there is usually a degree of shame or self-judgment for having indulged in this reactive pattern. Third, the feelings of sadness and loneliness that we tried to avoid with the ice cream return again. Freud called this “the return of the repressed.” And as Einstein said, energy is neither created nor destroyed, it just changes form. In other words, our attempts to escape the feelings that we have determined unacceptable only fuels further feelings that in turn reinforce our habits even further. What we push away always returns with the same amount of force we expended to keep it at bay.

What would happen if instead of going to the freezer when experiencing the growing or even acute feelings of sadness or loneliness, we sat down and paid attention to our breath? Yoga asks us to stay with feelings without seeking to avoid them. This does not mean dwelling in or indulging feelings indefinitely—such an approach can turn into another form of storytelling. Rather, it means that we stay patiently and with an attitude of acceptance with whatever is occurring in the present moment as it arises, unfolds, and passes away. Just put your body there. Instead of going to the freezer, allow whatever feelings are arising to unfold, however uncomfortable, in order for them to be felt fully and eventually let go of.

Staying present with feelings—especially negative feelings, such as physical or emotional pain—requires an attitude of patience and intentional acceptance. Breathing with uncomfortable feelings requires both steadiness and ease and the ability to explore our experience without judgment or distraction. Mindful awareness is nonconceptual, nonjudgmental, sometimes nonverbal, and exploratory. Pure awareness is not the extinguishing of the self but rather the stilling of the construction of the story of “me” as it arises. The stilling of these fluctuating stories is not the goal of yoga but rather the final technique by means of which we can wake up to the reality of a present moment not obscured by self. This is where the path of yoga begins. The mystic Kabir describes the way in which habitual conditioning and our preoccupation with ourselves has the tendency to hijack our spiritual practice:

Friend, please tell me what I can do about this world

I hold on to, and keep spinning out!

I gave up sewn clothes, and wore a robe,

But I noticed one day the cloth was well woven.

So I bought some burlap, but I still

Throw it elegantly over my left shoulder.

I pulled back my sexual longings,

And now I discover that I’m angry a lot.

I gave up rage, and now I notice

That I’m greedy all day.

I worked hard at dissolving the greed,

And now I’m proud of myself.

While the mind wants to break its link with the world,

It still holds on to one thing!1

Like a magnetic force, the habit of orienting our experience around the axiom of “I, me, and mine” is extremely difficult to undo, because as an addictive habit, it has great momentum. So the first step is to witness how the mechanism operates from moment to moment, and there are practical ways of doing this.

The first step of extinguishing this cycle of satisfaction-dissatisfaction is to use the power of naming, which is a linguistic tool of the mind. The mechanism of using language to name (nama) something is called buddhi. The term buddhi means “intelligence” and is where the mind can recognize something through language. Language allows us to recognize our experience, and usually when we are caught up in something, it is hard to name it. Therefore, naming acts as a way of finding the right distance from sensory objects (ālambana) as they appear in awareness so that we can notice what is there rather than slipping into reactivity. There is a difference between naming something and telling stories about it. Language helps us orient ourselves to the object of awareness, and once there, we drop into feeling without storytelling. When we give up our stories, we can usually feel experience with much greater sensitivity, compassion, and clarity. Nonattachment does not mean dissociation; it actually connotes connection and engagement with what is. Nonattachment does not prevent compassion; it sets up the conditions for it.

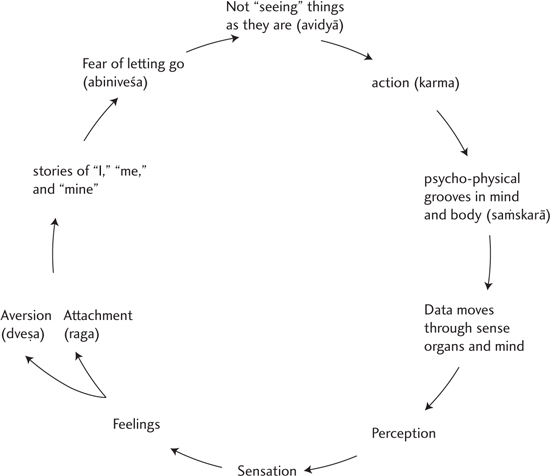

When we are in a difficult yoga pose, as an example, and pain arises in the legs, we stay with the pain by reminding ourselves to stay with leg, hip, breath, and so on, rather than telling ourselves the same habitual stories we usually tell when faced with strong sensations. So naming is a powerful tool that helps us recognize and investigate our experience. But once it has been named, we don’t proliferate the moment with stories; rather we remain present with whatever is (see diagram 3).

Diagram 3

Tapas

When we stay with feelings in mind-body, whether emotional or physical or both, we are in a way staying in the tension of opposites. This is called “tapas.” When we can stay with a feeling without attachment or aversion, we experience the practice of tapas. Traditionally, the term tapas referred in Vedic times to the fire at the center of a sacrificial ritual. In the Vedas, rituals revolved around sacrifices, in which, through the burning of various objects, a symbolic offering to the gods secured one a beneficial place in future existence. Over time, the term tapas took on a more subtle meaning. In the Upaniṣads, tapas refers to austerity, concentrated discipline, penance, or heat. The term was used to refer to a student who is burning with aspiration or a practitioner who is burning with intensity to know the truth. In the Yoga-Sutra, however, it took on a more psychological meaning: the heat of staying in the tension of opposites.

In any given moment, we can meet that moment with the conditioned habits of attachment and aversion, or we can meet that moment with spontaneity and freedom from conditioned responses. Carl Jung defined tapas as the “transcendent function,” which refers to the creative moment that occurs when we stay in the tension of opposites. Tapas, therefore, can be defined as “patience.” The practice of tapas is a practice of patience.

When we perpetuate the realm of binary thinking—likes and dislikes, me and mine, inner and outer—we fail to embody the root meaning of yoga—the ultimate interconnection and nonseparation of existence. This is not a reality without feeling or a life dissociated from the world but rather the ability to be fully engaged in life with the ability to experience fully its impact. Tapas is being grounded in a reality that is not “apart from,” and the skill of “grounding” is the activity of feeling what is without plotting escape routes. It is the ability to stand still in difficulty that makes new ground. Patience and stillness strengthen the very ground we stand on.

The work of tapas, which is the essence of yoga, is the cultivation of the skills that allow us to be present in the here and now with whatever is occurring, whether positive, negative, or neutral. Yoga is the instrument by which we hold ourselves in the fire of habit until we burn away that which averts the heat of change. Staying with habit and the paradoxical discomfort of letting go is what not only contains the process of yoga but fuels it. Pantañjali says it’s a great victory when you can experience a feeling as a feeling. In other words, eventually through this practice we can begin to experience feelings as feelings—impersonal phenomena as opposed to feelings in the form of explosive dramas of “I, me, and mine.” Feeling is the key to the present moment. It anchors us in experience.

Staying present in any moment of experience creates new patterns in the mind-body. To illustrate this in terms of psychophysiology, imagine making an impression of a coin in a lump of clay. In order for the impression of the coin to appear in the clay, changes must occur in the clay—the shape of the clay changes as the coin is pressed into it. Similarly, the neural circuitry of the brain, the pathways of the breath and nervous system, and the anatomy of the body must organize in response to new experience or sensory stimulation. Whenever there is a moment of nonreactivity, this is a moment of action. This is the action of nonaction. Whatever you reflect on frequently becomes, over time, the basic inclination of your mind. Not reacting in habitual ways creates new patterns, which in effect create new and more wholesome patterns of mind, body, and speech. This is the physiology of karma. Every action has an effect, even the action of nondoing.

Tapas is the key to yoga because being able to sit in the midst of opposition creates the heat necessary for change; yoga occurs when we let opposites move right through our pores, only to see that opposition is a conceptual designation that falls away when we are with the energy of the moment rather than with our storytelling. In patient openness, what was habit and immobility becomes receptivity and the capacity to open to experience. Whether this paradox is in the alignment of yoga postures, internal and external rotation in the leg bones, feeling the space between the in-breath and the out-breath, or the cultivation of stillness when habit pulls us into its familiar arms, it is paradox that creates new opportunity. Yoga occurs in paradox when, through tapas, two opposing energies have lost their pull and reveal a completeness. When our attention is on the relationship between opposing energies, they lose their oppositional tension, because we focus on their relations, not their substantiality.

Freedom from Duḥkha

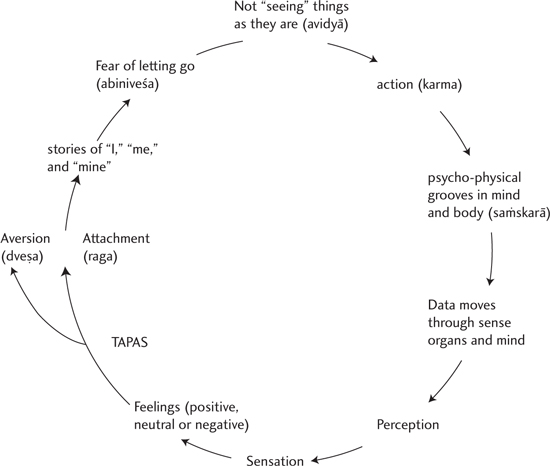

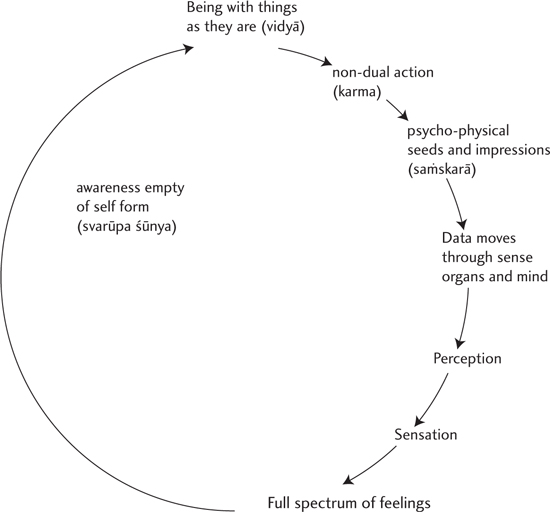

Reviewing the diagram that depicts the wheel of suffering, Patañjali asks the practitioner to consider what can be removed from this cycle and still have a functioning, healthy human engaged in relationship? The answer for Patañjali (as illustrated in diagram 4) is to slice the wheel in half.

Diagram 4

Instead of reacting to feelings, we pay attention to what is occurring in the present moment and, in doing so, take actions that reinforce patterns in the mind-body that create the conditions for being just as present in the next moment. In contemporary neuroscience, this is called “neuroplasticity.” Neuroplasticity sees the brain as an organ not separated from mind or body, and describes the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. By sprouting new nerve endings, the brain constantly changes within the context of its environment. It is not a closed system. Like the theory of the saṁksāras, the mind-body is not a closed loop. Our habits, predispositions, attitudes, and behaviors are open and flexible systems constantly in motion, subject to change, and they grow increasingly complex in order to become more and more efficient.

We expend so much energy running away from reality. Most of us are familiar with mind states that operate like closed circuits, perhaps repetitive cycles of addiction or ways of arguing with loved ones that seem infinite in their repetitive cycles. We know, too, what it is like to be lost in thoughts of past or future over and over again. The key in the model of the five kleṣas is that though the mind-body is contracted in states of addiction and delusion, this self-centered and inflexible posture is not permanent. A moment of suffering can also become a path out of suffering. The very intensity of each one of the kleṣas, when experienced fully, pushes us into seeing where the mind is fixed and to what it is holding on. Unlike the detached state of pulling away from experience, nonattachment creates flexibility by bringing us closer to what is actually occurring, even as we are less encumbered by our viewpoint. Relaxing the heart when we see contracted states arising disentangles us from the web of self-identification.

Yoga practice is about expanding and strengthening circuits in the mind-body that are less frequently used, and repatterning those that are inefficient. This is called “nirodha.” Nirodha is the releasing of habitual patterns or fluctuations in mind-body, but it also describes the energy that comes from that letting go of old patterns.

In yoga, instead of taking a pilgrimage to a particular mountain or temple, we take pilgrimage inside of our own bodies. For most people, this is a more difficult pilgrimage. To walk through the landscape of the body open to feeling whatever feelings arise puts us in touch with the core of the body. However, there are many psychological, emotional, and physical holding patterns in the center of the body that make this pilgrimage difficult. That difficulty is also our potential for liberation.

If we look at diagram 5, on the left-hand side we see a model of duḥkha (from attachment/aversion all the way to avidyā), and on the right-hand side we see a model of a personality free from the constraints of a conditioned existence of stress and discontent. On the left-hand side, we see a constructed and illusory clinging to self; on the right-hand side we see the spontaneous expression of a personality free from the need to create self. When you no longer need to create a sense of self, you are free to be yourself. In this way you can use the mind to create a more solid base from which to see and take action; however, the solid base is not ontologically substantial but rather the psychological sense of being existentially grounded in the midst of change.

Diagram 5