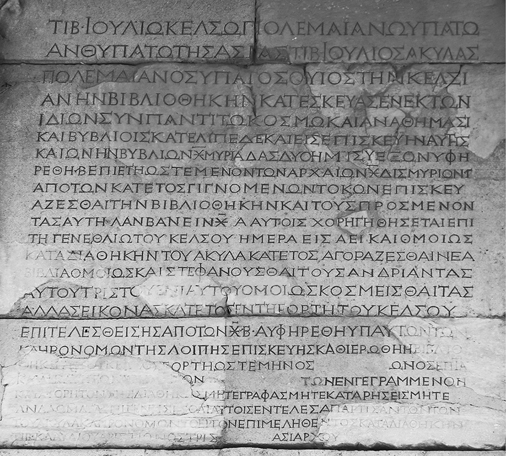

FIGURE 2.1 Celsus Library façade, Ephesus.

(Photo courtesy of author)

ANCIENT LIBRARIES ARE often thought of as destinations for books, final resting points where those texts fortunate enough to be included found a permanent home, safe (or so their authors hoped) from the depredations of fire, neglect, decay, and worms. This picture is partly due to an authorial trope, common by the Roman period, in which inclusion in an imperial library featured as an ambition or boast. The late first century CE epigrammatist Martial, for example, asks for his works to be shelved in the Emperor Domitian’s newly rebuilt Palatine library, in a sycophantic poem addressed to the librarian Sextus (5.5):

Sextus, eloquent votary of Palatine Minerva,

You who enjoy more closely the genius of the god – –

For you are permitted to learn the cares of our lord as they are born, and to know our leader’s secret heart –

Could you find a place somewhere for my little books

Where Pedo, where Marsus, and where Catullus shall be?

By the divine song of the Capitoline War

Place the grand work of buskined Maro.

Authors aspiring to the inclusion of their works or statues in Roman imperial libraries range from Horace under Augustus, to Josephus under the Flavians, through to Claudian around 400 CE,1 while the preface to the supposed Latin version of the Ephemeris of Dictys Cretensis aims at verisimilitude by setting out the text’s complicated journey through time and space, culminating in a permanent home in one of the emperor’s libraries:

… shepherds who had seen [the original text] as they passed stole it from the tomb, thinking it was treasure. But when they opened it and found the linden tablets inscribed with characters unknown to them, they took this find to their master. Their master, whose name was Eupraxides, recognized the characters, and presented the books to Rutilius Rufus, who was at that time governor of the island. Since Rufus, when the books had been presented to him, thought they contained certain mysteries, he, along with Eupraxides himself, carried them to Nero. Nero, having received the tablets and having noticed that they were written in the Phoenician alphabet, ordered his Phoenician philologists to come and decipher whatever was written. When this had been done, since he realized that these were the records of an ancient man who had been at Troy, he had them translated into Greek; thus a more accurate text of the Trojan War was made known to all. Then he bestowed gifts and Roman citizenship upon Eupraxides, and sent him home. The Greek Library, according to Nero’s command, acquired this history that Dictys had written, the contents of which the following text sets forth in order… .2

Both passages present acquisition by a library as a desirable, even glamorous mark of approbation for a book, the culmination of a journey. One important reason for this aspiration was that such acquisition offered the chance of being read. Ancient libraries accumulated literary texts, not, or not only, as an end in itself, but also in order to transmit the works they held to readers, both of the present and of the future. This exposure to readers is part of what Martial wants for his work, and it is as a reader of a library text that “Lucius Septimius,” the Dictys author, presents himself. But both texts also show us that the worth that these ancient libraries had for authors, and indeed for their patrons and builders, was complicated and multivalent. Libraries were more than just a final destination for books or even a place to read them; they also acted as points of communication of several different kinds.

Martial’s poem expresses the hope that his work will be shelved alongside that of famous poets of the past, specifically of Rome’s late republican and early imperial periods (Marsus, Pedo, Catullus, Virgil).3 Just as the “divine song of the Capitoline War”—a civil war epic that was quite possibly a juvenile work of Domitian himself4—should be shelved alongside Virgil, so, too, Martial wants his own epigrams placed alongside Augustan-era poems. He seems to hope that some of their luster would thereby shine on him. Libraries, by selecting and grouping works of literature, had the capacity to endorse or exclude, canonize and compare, as well as act as places for communication between patrons, readers, writers, and public audiences. Moreover, Martial reminds us that libraries, by gathering and preserving a range of texts in one space, not only encouraged comparison between those texts in the present day, but also allowed for their communication through time rather than over distance. Martial hopes to be commended to posterity in the company of authors already granted immortality through their work, and he hints sycophantically that Domitian, as the library’s patron, would similarly gain from his association with literary genius.

The Dictys author shows us other perceived functions of libraries in the ancient world. He implies that he compiled his own Latin version of the text by reading the Greek translation commissioned by Nero for his library, which serves as an authenticating landmark in this extraordinary chain of transmission. We can leave aside here the question of the truthfulness of this well-known pseudepigraphon. Rather, the point—as with dubious references to libraries in the Historia Augusta5—is the author’s aim of creating an impression of verisimilitude and reliability in which the reference to an imperial library plays a part, making use of such libraries’ reputation for housing authentic literary treasures and for serious scholarly writers consulting them there. For both Martial and “Septimius,” the library is not a dead-end repository, but an important link in a chain of transmission, comparison, and authentication between texts of the past, present, and future. As we will see, libraries played an important part in networks of literary communication throughout the ancient world, and in other sorts of communication, too—political, philanthropic, imperial.

This view of the ancient library as a point of communication fits well with current scholarly work on the subject, which is increasingly interested in ideas, not only about the stability of libraries as destinations for books, but also about the more dynamic ways in which they allowed the exchange and transmission of ideas and facilitated the mobility of people, objects, and texts. This interest reflects new ways of thinking about the roles of literacy and literature within the classical world since William Harris’ landmark study (1989), broadening the scope of inquiries about the place of texts in the ancient past. Recent work—as that by Johnson and Parker (2009), for example—considers the plural ways in which different kinds of texts and reading were embedded in different social contexts, and examines the boundaries and interdependence between oral and written, public and private, literary cultures. This work is influencing how we now think about libraries in the ancient world. The old view that they were places with no “large-scale effect on the diffusion of the written word,” open only to a small range of the “learned and respectable,”6 is giving way to studies that approach them from new angles and seek to place them in their social, architectural, cultural, and urban contexts, as well as to compare them to the text collections of other times and places.7

Eleanor Robson’s work on Assyrian and Babylonian libraries, for example, indicates that these were both compendious collections and also active points in a distributed network of readers and texts.8 For the classical world, Yun Too (2010), writing on the “idea of the library,” considers not only the physical fabric and holdings of “book-libraries,” but also their capacity for political and social interactions of various sorts, and thus seeks to broaden our understanding of what a “library” might consist of. Read in conjunction with recent work on the role of literature in social and political identities, particularly in the Greek East under the Roman Empire,9 such work allows us to reconsider the libraries of this Greco-Roman world. Though this chapter will deal mostly with institutional libraries occupying designated physical spaces, the wide range of ways in which the communicative functions of these libraries can be considered owes much to these new approaches to literary reading and writing, circulation, and performance.

IN THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD, the earliest book collections that we know about were the initiative of sixth-century BCE kings or tyrants: Pisistratus of Athens and Polycrates of Samos.10 Although there is little detailed information about the nature or accessibility of Pisistratus’ book collection, we do know that, as well as accumulating a library, he presided over an effort to collect and refine the oral Homeric epic poems into standardized written editions—in which, not coincidentally, the city of Athens and its founder Theseus play a somewhat greater role than one might otherwise have expected.11 If (as seems reasonable) his Homeric project was connected to the book collection, whether conceptually or practically, then we can see here a “library” linked to ideas of royal power and civic prestige in an age when Greek-speaking city-states in general, and Athens in particular, were developing a rich, bibliocentric literary culture.

Such a role for libraries was greatly amplified by the Hellenistic kingdoms, which spread Greek city culture over wider areas than previously, across an arc from Egypt to Afghanistan. These kingdoms had far greater funds at their disposal than the city-states they replaced, and perhaps a greater need to define, assert ownership of, and promote Greek culture. Greek-style cities with rectangular street grids, theaters, and gymnasia spread as far as Afghanistan, and the competing dynasties sought (as had Polycrates and Pisistratus) to establish their cultural credentials as one justification for their royal power, at least when speaking to Greek audiences. In this ambition, book collecting—patterned after the libraries of the Greek philosophical schools and particularly Aristotle’s Lyceum12—was one important tool among many. The foundation and maintenance of libraries in city gymnasia across the Hellenistic world of the second and first centuries BCE suggest that institutional book collections were also important for education and for cities’ cultural life at a local level.13

The library at Alexandria is of course by far the best-known example, though not the best preserved. At Pergamum, by contrast, a room commonly identified as “the library” survives, adjoining a suite of smaller spaces and opening onto a temple colonnade.14 The collection policies of both the Alexandrian library and this Pergamene rival were famously wide-ranging and aggressively competitive, making such libraries increasingly central points in a network of literary-political interactions around the wider Greek world. Most famous of all is the story that Ptolemy III Euergetes “borrowed” the original copies of the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides from Athens15—an interesting testimony that Athens had some sort of official civic collection from which to lend them—and then deliberately forfeited his enormous deposit by keeping the books and sending back only copies. This sounds like a studied gesture, making the library’s power to acquire books a symbol of Alexandria’s eclipsing of Athens as a center of political and intellectual power. Similar is the elder Pliny’s unlikely story that an embargo of papyrus exports from Egypt by the jealous Ptolemies led the rival Attalids of Pergamum to invent parchment as a writing surface.16

The Alexandrian library and “museum” (Mouseion) in particular afforded a meeting place for communication between scholars, texts, and readers, and as such was part of a network of movement and exchange of people, books, and ideas, not (or not only) a static repository. Strabo’s description of the museum’s physical layout includes space for discussions, walking, and reading, not unlike the remains at Pergamum.17 One famous (jealous?) reaction is found in a fragment by a contemporary skeptical philosopher and satirist, Timon of Phlius: “In populous Egypt many cloistered bookworms are fed, arguing endlessly in the chicken-coop of the Muses.”18 But it is clear that the library and museum acted from the outset as places for scholars to meet and interact, both with each other and with each other’s writings. The Alexandrian library quickly became a central point in the wider network of Mediterranean book-use and scholarship, with the Athenian exile Demetrius of Phaleron involved in its establishment and many scholars from around the Greek-speaking world attracted to it: the more important included Aristophanes of Byzantium, Callimachus and Eratosthenes of Cyrene, Aristarchus of Samos, and Zenodotus of Ephesus. The library had the desired effect of pulling in scholars from all across the Greek-speaking world, turning Alexandria within a generation from a new town into the prime center of Greek scholarship for at least two centuries.

Within the library, books in the steadily accumulating collection could be compared to each other—as happened particularly extensively in the case of variant texts of Homer—to produce critical editions, glossaries, and commentaries. In the course of this work, Alexandrian scholars invented, refined, or accelerated the adoption of numerous bibliographical and scholarly tools: glossaries, commentaries, grammars, the development of a standardized form of koine Greek written with accentuation, some punctuation and critical signs, the use of alphabetical order, and the classification of literature by genre, sub-genre, and author (in the extensive Pinakes or catalog compiled by the poet, scholar, and possibly librarian Callimachus).

The library and Mouseion also acted as loci of communication between scholars and the patron Ptolemies, who participated in discussions and lectures and whose children were often tutored by the librarians. The library’s reputation played a part in making the king appear learned and his kingdom prosperous and enlightened, a criterion of Hellenistic-Macedonian kingship.19 It therefore acted as a form of communication between king and subjects, and between rival dynasties: we shall encounter this capacity of the library for public display again in the Roman period.

The library may also have played a part in managing the difficult relationship between the Alexandrian Greeks and their Jewish neighbors, if we can lend any credence to the Letter of Aristeas. This text of around the second century BCE claims that at least a portion of the Jewish scriptures20 were translated from Hebrew into Greek as part of the Alexandrian library’s program of acquiring translations of foreign works. The text quotes a memorandum of the librarian Demetrius in which he tells the king that the Jewish scriptures are “somewhat carelessly committed to writing and are not in their original form; for they have never had the benefit of royal attention”—an implied comparison with the works of Greek literature, particularly Homer, set into order by the scholars of the royal library and Mouseion. Aristeas’ Demetrius goes on to tell the king that “these books, duly corrected, should find a place in your library, because this legislation, inasmuch as it is divine, is of philosophical importance and of innate integrity.”21

Aristeas claims to have been sent by Ptolemy II to Jerusalem to act on this advice, taking gifts and requesting the loan to Alexandria of a team of seventy-two priestly translator-scholars; the result was what we call the Septuagint, named for a rounded total of its translators. The Letter, like the Dictys Cretensis and the Historia Augusta, is improbable in its details and in its overall scope, which aims at praise of Ptolemy’s wisdom and reconciliation with the Jews. But if we can believe that there is at least a kernel of truth in it, it shows us that Ptolemy was famed for a catholic program of collection for his library at Alexandria, and that Demetrius as his agent was empowered to spend freely, and to borrow and accommodate scholars. He could provide a place for study that contributed directly to the holdings of the library, which itself was an agent of mobility and translation and a vector for texts. We might also consider that Manetho, an Egyptian priest at Heliopolis, wrote and dedicated to Ptolemy II Philadelphus a history of Egypt in Greek, drawing on Egyptian documentary sources; equally, that Callimachus’ student Hermippus wrote a commentary on the verses of Zoroaster, implying that they were available in Greek translation from the original Iranian.22

The library at Alexandria was therefore part of a lively and active literary culture. It acted, not just as a royal storehouse, but also (along with the Mouseion) as an organizing point for scholarly activity, comparative reading, and writing. It was a place scholars were attracted to, and where they then encountered each other; also a place where the developing canon of classical literature had at least some interaction with literature of other cultures. At the same time, to be sure, Alexandria was a bottleneck restricting the dissemination of books, and a vulnerable repository, too. The second problem is evident in retrospect, but it did not escape ancient authors: they relished tales (almost certainly false, or exaggerated) of Alexandria’s destruction and similar library fires in Rome,23 and occasionally moralized on the preferability of memory and intellect to reliance on written texts.24 Nonetheless, there is considerable evidence that, over the centuries, these libraries made important contributions to the cultural life of the ancient world.

THIS FUNCTION OF the library as a nodal point in a network of communications across an empire continued into the Roman period. Rome’s emperors sometimes poached Alexandria’s chief librarians to come and direct imperial libraries in Rome; Claudius even had his own Etruscan and Carthaginian histories read out there annually in an imperial display of vanity publishing.25 By this time, Rome had developed a lively literary culture of its own, in which the material and intellectual heritage of the Greek literary world played a part: Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artes intulit agresti Latio.26 Primacy in book collecting and book scholarship gradually passed to Rome throughout the first century BCE and later, as Rome first imported (by plunder and purchase) book collections from its eastern conquests and then, once established as a center of learning, began to attract scholarly readers and writers much as Alexandria had done.

Initially, Rome’s libraries were the private resources of the rich, sequestered in their villas and open only to their private circles of learned friends and dependents. In the first instance, these Roman library-owners were the generals who captured entire libraries from vanquished foes in the Greek world and re-established them on Italian soil as centers of reading, discussion, and the production of new texts. The Aemilii Paulli acquired the library of the Macedonian king Perseus after his defeat at Pydna (168 BCE), and within a generation, they were acting as literary patrons, of the émigré Greek historian Polybius among others.27 A century later, the Pontic booty of L. Licinius Lucullus, Sulla’s literary executor and triumphator (63 BCE), formed the basis of another villa library praised by Plutarch (Luc. 42), not only as a magnet for expatriate Greeks, but also as a center of scholarship, explicitly compared to the Mouseion at Alexandria, and described as an unofficial “embassy”:

What he [Lucullus] did in the provision of books deserves serious esteem. For he collected together many books, and they were well written. His use of them was more honorable than their acquisition, since he opened up to everyone his libraries, and the colonnades around them, and the rooms for study, so that they welcomed in the Greeks without hindrance, as if to some lodging-place of the Muses. They would go to and fro there and spend their days with one another, gladly escaping from their other obligations. Often he himself would spend his leisure time there too, walking about in the colonnades with the scholars, and would help the statesmen with whatever they needed. And, all in all, his house was a home and a Greek prytaneium for those coming to Rome.

Although Cicero in turn amassed his own very substantial collection (through purchase rather than conquest), we know that he, too, read and wrote in Lucullus’ library. His De Finibus mentions its containing volumes of Stoic philosophy as well as many commentaries on Aristotle;28 moreover, fragments of the lost Hortensius (which Cicero set in the library) suggest that it included holdings in tragedy, comedy, and lyric poetry.29

For the physical appearance of a late-republican private library, we can look at the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, an opulent seaside property named after the carbonized book scrolls that were discovered there in the late eighteenth century, preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius. The contents of these books suggest that the villa, or at least the book collection it housed, was used by the first-century BCE Epicurean poet and philosopher Philodemus and his circle, and that it acted as another lively hub of learned interaction.30 The private wealth of its patron (possibly Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus) attracted both prestigious Greek scholars and their books; Philodemus was an influence on both Horace and Virgil. Again, we are in a world of mobility, exchange, movement, and communication, in which large book collections acted as important focuses of international scholarly activity, one of the resources—along with architectural space and comfort, food, money, intellectual company, and prestige—that a patron could deploy.

Within a few years of Philodemus’ and Piso’s time in Herculaneum, the Roman republic collapsed in the civil wars, which ended with the emergence of the first emperor, Augustus. The new regime amassed huge resources from the confiscated or inherited property of defeated enemies and nervous new supporters. The foundation of the Roman world’s first public libraries was among the results, even if the honor of actually founding the first such library at Rome belongs to the independent-minded and literary politician Asinius Pollio. Private libraries continued to flourish into the imperial period: Athenaeus’ account of Larensis’ library and Martial’s dispatch of his book to Stella’s both show the power that private literary patrons continued to wield through their libraries.31 However, they were joined by the public libraries of the imperial capital and, in time, by public libraries built in the empire’s provinces.

Assessing the genuinely “public” element of these buildings is difficult; no reliable testimony exists about entry control or numbers of visitors. Their imperial patrons did not intend them to fulfil the educational and philanthropic goals that we associate with the modern public libraries of Victorian times onwards. Nonetheless, it does seem that the new public libraries of the imperial period were constructed and discussed in new ways. The language used to describe their foundation includes repeated use of the verb publicare and its cognates—also used by authors to indicate the handing-over of their finished work to the public32—thus indicating a perception that these large book collections in their purpose-built homes were now in the public realm.33

This quality applies particularly to the libraries founded in the reign of the first emperor, Augustus. The new regime tried hard to establish its credentials as a friend and benefactor to the public at large, presenting to it for the first time resources and facilities that had previously been the preserve of men like Lucullus or Piso. In this regard, we can place the city’s libraries alongside the parkland, statue collections, paintings, and bath-houses opened up to at least nominal public ownership and use by the first emperors. We may see these resources as part of an idealized representation of the city to itself, a statement of the sorts of cultural and leisure activity that were attractive to Augustan Romans.

There are several other ways to consider these new public libraries and their book collections in the context of communication, from the obvious ways in which any library connects books with readers to more abstract communication functions. In the first place, these libraries existed to make books available to readers, “communicating” to an audience the literature they chose to accumulate. In this respect, they were the successors of the Hellenistic and private Roman republican libraries discussed above, at least some of which were assembled, not merely for royal or élite display, but also with the goal of fostering real literary and scholarly activity. This is not as uncontentious a claim as it might seem: almost as soon as books became familiar material objects in the Greek world, we hear of unlearned collection for mere social display—books bought “by the yard”—and Roman satire abounds in ignorant book collectors, the most famous being Petronius’ boorish millionaire freedman Trimalchio.34 The implication of the satire is that respectable libraries were meant to be useful and used rather than, or as well as, decorative; praise was duly bestowed on a Ptolemy or a Lucullus who achieved that goal.

This ethos seems to have informed the earliest public libraries in Augustan Rome. Horace, a subtle exegete of the Augustan literary program, talks about the books in the Palatine library being widely read and well known.35 Ovid, who fell afoul of Augustus and wrote a series of mournful poems from exile on the Black Sea asking to be let back into Rome, described the holdings of Rome’s new public libraries thus:

Whatever men of old or more recent times conceived in their learned hearts lies open to be inspected by readers.36

Generally speaking, the testimony regarding these libraries presumes, as Ovid does, the active presence of readers and other sorts of visitors. These new imperial public libraries were therefore naturally attractive to authors, who wanted their books to be read both by contemporaries and by future generations; libraries, after all, have the potential to guard books and present them to posterity. The monumentum aere perennius and the κτῆμα ἐς αἰεί are standard classical literary tropes. Conversely, Roman writers knew well the various fates that could befall an unlucky book, whether it be destroyed by flame, damp, or the worm, not to mention used as waste paper in wrappers for mackerel (as Catullus fears) or pepper (as Horace fears), or for other even less-savory uses.37

Accession to one of these imperial libraries offered an apparent guarantee of preservation and status, as we saw in Martial’s plea at the beginning of the chapter. Libraries, with their dedicated staff of copyists and binders, their prestigious high-quality copies, and their solid, secure buildings in important parts of town, apparently offered the best chance of achieving permanent literary survival down the ages, better certainly than the cheap popular copies that Ovid’s exile poetry was doomed to depend upon—though we might note in passing that his poetry has survived, while many rivals given prestigious accommodation in Rome’s libraries have not.

LIBRARIES THEREFORE TRANSMITTED the best of the past to the present, and the corollary is that they could also transmit present works into the future, shelved in the illustrious company of authors who had definitely “made it.” As the elder Pliny says in a discussion about the decoration of libraries with authors’ busts, libraries are places where the immortal spirits (immortales animae) of past authors speak to us—in the present tense, as if they were still alive.38 The newly discovered work by Galen, Avoiding Distress, gives us a real illustration of this claim, showing that the Palatine library apparently managed to keep recognized collections of books intact on its shelves for over two centuries. Learned readers could consult reliable master-copies there as late as 192 CE, says Galen (13):39

… works that were rare and not preserved anywhere else, (and) copies of standard works that were prized because of the precision of their text, those of Callinus, Atticus, Peducaeus and even Aristarchus, including the two Homers, and the Plato of Panaetius and many others of that sort, since preserved inside in each book were the words either written or copied by the individuals after whom the books are named. There were also many autograph copies of ancient grammarians, orators, doctors and philosophers.

This ability of libraries to make connections across time—grouping authors of the present day alongside those of the past, and making implicit or explicit comparisons between them—meant that accession into an imperial library came to be regarded (like acceptance into the Ptolemaic circle at Alexandria) as a mark of both political favor and literary success. At Rome, this favor could be exercised through libraries in various ways. These ranged from direct patronage and active collection to simple interest, as when the Emperor Tiberius placed portrait busts of his own favorite poets (Euphorion, Rhianus, and Parthenius) in the libraries at Rome, an action that instantly stimulated the writing of several commentaries on them.40 Outside Rome we can compare the pleasure expressed by the florid second-century CE Greek orator Dio Chrysostom at being honored with a statue in the public library at Corinth. Its presence, he felt, would spur the youth of the city to make even greater efforts in their studies.41

Conversely, imperial displeasure could also be exercised through libraries. Ovid was excluded under Augustus after his exile;42 Caligula, in a moment of characteristic caprice, tried to ban the classic works of Livy and Homer from Rome’s public libraries.43 In all these stories, libraries are loci of imperial engagement both with literature and with a wider audience, an arena for gesture politics. The point is picked up by the authors who tell us the stories, selecting these episodes as illustrative of an emperor’s attitudes. Libraries could therefore function as places where the circulation, exchange, inclusion, and exclusion of texts communicated political as well as cultural and intellectual values.

Looking at how these Roman libraries were actually used suggests that they functioned, as at Alexandria, as centers of interaction, exchange, and communication between scholarly readers. Aulus Gellius, for whom libraries are one of many agreeable settings for literary discussion, is a good source in this connection. During a lively discussion he records on a question of grammar, for example, the eventual answer is “Go and look it up in the Templum Pacis library,” as if appeal to the authority of the library offered an unimpeachable final answer in such a dispute.44 Elsewhere, we find Gellius browsing in the Library of Trajan,45 or recording a semi-formal learned conversation set in the Domus Tiberiana library between himself, the eminent scholar Sulpicius Apollinaris, and an unnamed youngster (adulescens)—evidence that a rather mixed usership, not all already known to each other, could meet, sit, and talk together in these libraries.46 For Martial, the libraries of Rome, alongside its theaters, were places that afforded opportunities for pleasurable study and inspiration.47 Galen helps confirm this picture when he calls the Templum Pacis library “the place where all those engaged in the learned arts would gather before the fire” [in 192 CE].48 Large book collections authenticate, enable, and provide a backdrop to living interactions in these anecdotes—altogether a fairly common function of libraries in the literary record.

This function was probably enhanced by the confining of books to libraries. There is mixed evidence for borrowing from libraries, but on the whole, it seems that it was usually forbidden, meaning that readers generally came to the books rather than vice versa; library books, after all, were prestigious and expensive objects. The well-known inscription from Athens listing the rules for the late first-century CE library of Pantainos there supports this impression, stating that “the library is open from the first to the sixth hours; no book may be taken out—we have sworn it.”49 Galen’s new testimony suggests that the Palatine library, too, cannot have lent its books out, given their apparent survival as complete collections over two and a half centuries.

Readers were therefore drawn to public libraries, increasing the potential for the sorts of encounter described above. The number of visitors was boosted by the fact that libraries could also function as a venue for public oral displays of literary endeavor, like lectures and debates, as well as for the display of works of art. Roman library rooms themselves—unlike what we know of their Hellenistic and Republican forebears—were large.50 Augustus’ Palatine libraries were used for Senate meetings,51 so they must have been capable of accommodating large numbers of people for literary recitals or lectures. In his Florida, Apuleius, speaking from the stage of the theater in Carthage, says that if his audience hears anything especially learned, they should imagine that they are encountering his work in the town’s library instead, as if the town’s theater audience were familiar with the library as well.52

Roman public libraries also seem often to have been associated with separate, purpose-built spaces for public events such as the lectures, recitations, or disputations that characterized much of the public intellectual culture promoted by the second-century CE literary revival, termed the Second Sophistic. It is probably in the Templum Pacis complex that Galen, for example, sets a formal refutation of his critics in the format of a public lecture and demonstration described by him in On My Own Books. This event took place, Galen tells us, “in one of the large lecture halls.” So the building incorporated more than one hall suitable for lectures; the one used by Galen probably contained (or was attached to) a library with extensive medical holdings, because he began his display by setting out in front of himself a huge range of anatomical books. The Hadrianic library at Athens contained twin auditoria or lecture rooms with raked seating flanking the central book hall. This Roman-style library built by Hadrian at Athens sounds rather like Sidonius’ descriptions of the Athenaeum, which Hadrian built at Rome as a “school for the liberal arts.”53 The excavation required there for a new subway station adjacent to Trajan’s Forum is now bringing what may be this building to light—commodious lecture halls with wide, shallow-stepped seating.

LIBRARIES IN THE Roman world were therefore places of reading, and also of meeting, discussing, debating, and listening: in short, they acted as centers and catalysts for various sorts of literary communication. Is it possible to determine whether they also communicated with a wider public, beyond the confines of the literary men we meet in the sources cited so far? The sheer number of public libraries, not only in Rome (twenty-eight by the time of Constantine in the early fourth century), but also in the provinces of the empire, particularly the east, suggests that they had a public character as a familiar part of the urban landscape. Among other functions, the provincial libraries were used as points of communication in the dissemination of literature between Rome and the wider empire. Galen’s Avoiding Distress, in which he talks about the circulation of his own books, says that one copy of each was intended to satisfy the requests of “friends back home,” who “were asking for copies of my writings to be sent to them so that they could deposit them in a public library, just as others had already done with many of our books in other cities.”54 These public library copies would presumably guarantee as wide an exposure to the text as possible, and, crucially, the preservation of a reliable copy.

We can compare Galen’s earlier approval of the authenticity of the Palatine library’s precious texts, and note that he views his own works as part of this tradition. The process still relied on the agency of trusted friends, whom the recipient library could in turn trust to have received the original work directly from Galen; but it must aim at a wider circulation than whatever could have been achieved by circles of friendship alone. For Galen, the use of a public city library to hold his text overcomes the risk of misattributed or miscopied versions’ circulating—we may recall how keen he was himself to use imperial public libraries in Rome because of the excellent provenance of their holdings—and points us to a role for the provincial public library that mirrors an important function of its Roman counterpart.

What we see is a role for the Roman library as a nodal point in a network of communication, in which geographically dispersed agents (readers and writers) used libraries as mutually acknowledged central points of contact. Provincial libraries made use of contacts with men of letters at Rome, and in turn were trusted to house reputable copies of new works and make them available to provincial readers. In the terms of modern network theory, libraries could thus be seen as elements in a material-semiotic network of “nodes” and “ties,” in which people, material objects, places, and concepts communicated across the Greco-Roman world. In such a network—one constantly renewed through the actions of its members—certain members can act as points of connection, or “hubs,” between individuals, small local groups, and the wider world. Libraries, with their capacity to collect, preserve, and make texts available, were equipped to fulfill such a role. Alongside other agents, they linked local, personal “effective networks” whose members were all known to one another into wider “extended networks,” capable of transmitting texts and ideas over greater distances to new audiences.55

Such an ancient literary network, however active and extensive, could not have included large numbers of people, in either absolute or relative terms. When we want to proceed beyond this privileged level and investigate the degree of genuine public access to library buildings or engagement there, it is hard to be precise. We can at least detect in their architecture a monumental function comparable to that of large public buildings throughout the city, designed to be seen and entered by plenty of people. We have noted that these buildings seemed to house recitals and debates, and we know that they contained high-status art works—all good reasons to attract large numbers of people into the buildings and to raise their public profile.

Moreover, public libraries were almost always located in extremely prominent parts of town, and they addressed passers-by with expensive and elaborate eye-catching façades. In Rome, libraries clustered round the monumental core of the city, occupying space on the Palatine hill, in the imperial fora, and (possibly) in lofty halls in the imperial bathhouses; they were always connected to some other large public complex. In the provinces, to take only a selection of examples, the library of Celsus in Ephesus with its ebullient facade occupies the most prominent and highly trafficked street corner in the city (Figure 2.1). The library at Timgad in Algeria covers an entire city block very near the forum in the center of town, offering passers-by an attractive colonnaded courtyard opening off a busy street. The Pantainos library in Athens sits prominently in the Agora at the junction of the Panathenaic Way and the road to the new Roman Agora, also advertising its presence with lateral colonnades and a statue display. While the number of scholarly users of these libraries was probably never more than a small proportion of the population, the libraries were still designed to be conspicuous public monuments, signifying cultural patronage and prestige to a large urban audience.56

FIGURE 2.1 Celsus Library façade, Ephesus.

(Photo courtesy of author)

LIBRARIES PERFORM COMMUNICATION functions quite distinct from the actual reading of the books: messages of imperial and local patriotism, engagement with metropolitan fashions, and communication between a city’s literary élite and the bulk of its population. Here, then, is another way libraries could act as places of exchange and transfer, and for more than just books: public libraries were used in the important civic business of self-promotion and commemoration. As with virtually all Roman public buildings, libraries carried long inscriptions naming their donors. The gift of a library reflected a certain cultural aptitude and intellectual worth, as well as engagement (as Galen shows) with high-level literary networks, not to mention material generosity and political ambition. Particularly during the period of the Second Sophistic, the cities of the Greek eastern half of the empire were governed by well-born groups of councilors, magistrates, and priests, whose grandest members mingled with Roman governors and even in some cases were admitted to the Roman Senate.57 A fluent command of the spoken and written language was a prerogative of these largely self-perpetuating civic élites, and indeed a criterion for membership in them. A large proportion of local government depended on speech-making and ambassadorial duties,58 so command of the discipline of Greek oratory was particularly valued and could be displayed before large civic audiences. In this sort of society, library buildings, paid for and bearing the names of men of this class, spoke confidently about their place in the empire and the place of a shared literary, cultural identity; they also helped negotiate the tensions in the relationship between local, cultural, civic, Greek, and Roman identities.

Some library buildings went to extraordinary lengths to communicate these ideas to the population of their cities. The façade of the Celsus library at Ephesus at first glance looks entirely typical of Roman-era buildings in the Greek east, with its elaborate projecting and receding screen of columns. But framing the three doors of the library are relief panels showing the consular fasces, the rods and axes that symbolized Celsus’ imperial magistracy in Rome, while twin equestrian statues of his son (the donor) flank the steps on bases inscribed with Celsus’ entire career in both Latin and Greek (Figure 2.2). The niches in the library’s façade house statues personifying Celsus’ intellectual virtues, labelled in Greek—his “Wisdom,” “Virtue,” “Knowledge,” and “Understanding,” all suitable to a library patron, even if strikingly immodest. The upper storey of the façade houses statues of Celsus and various family members with their inscribed careers, allowing the library to serve as a sort of billboard for the family’s virtues and success over several generations. The building’s dedicatory inscription shows that the provisions made for funding the library (with an endowment whose interest provided for staffing and book purchase) included an annual public feast on Celsus’ birthday, when all his statues would also be crowned with garlands (Figure 2.3).

FIGURE 2.2 Celsus Library doorway, Ephesus.

(Photo courtesy of author)

FIGURE 2.3 Celsus Library dedicatory inscription, Ephesus.

(Photo courtesy of author)

Here, therefore, the entire building is an exercise in mass communication, reaching out, not only through the texts it held, but also through exterior inscription in two languages, through the visual media of sculpture in the round and relief carving displayed across the front of the building, as well as even to the illiterate (or indifferent) through garlands and feasts. We could compare one Lucius Flavius Aemilius Tellur(ius) Gaetulicus, a near-contemporary library patron at Dyrrachium (in modern Albania), who tried to broaden the appeal of his gift by providing twelve pairs of gladiators to fight at the dedication.59 Overall, Celsus seems to have envisaged his library as a means of perpetuating his own memory in Ephesus, and that of his family, alongside the preservation of literary texts housed there. Indeed, his own sarcophagus is buried beneath the central apse of the library, looking out into it through two small holes cut into the molding of the library’s podium.

Clearly, such buildings do more than simply provide a secure storeroom for books and a place to read them. These libraries are confident displays of literary prowess, proud symbols of the acumen of both their founder-builders and of the cities where they were situated, and also statements of a shared Roman and local political-cultural identity. To judge by where firmly identified archaeological remains survive, in their architecture these provincial libraries adopted the lofty central halls, wall-niches for books, space for statues, internal colonnades, galleries, podiums, and fine decoration that seem to have characterized imperial examples at Rome. In fact, the striking early-second-century vogue for provincial library-building followed a period when the emperors Trajan and Hadrian built several libraries at Rome and elsewhere.

The frequent association between libraries and funerary monuments also echoes a Roman imperial example. In Rome, on Trajan’s death in 117, his ashes were laid to rest beneath the Column (with its famous helical frieze of the Dacian campaigns) erected between his two libraries. Around the same time, Celsus was buried in his library at Ephesus, a family heroön was set up in the possible library at Sagalassos, and Dio Chrysostom’s wife and son were buried in his library at Prusa.60 The connection between libraries and burial highlights the commemorative power of the library to transmit ideas to posterity, as we saw with the elder Pliny’s immortales animi. Library patrons seem to have hoped, both to emulate the emperor’s famous complex in Rome, and to be conveyed to posterity in the company of the authors they gathered around them, just as Martial wanted to be shelved among the ranks of great poets of the past. Libraries in the ancient world were points of communication between authors and readers, between groups of visitors, between speakers and audiences, and between emperors and subjects, the center and the provinces, local leaders and their cities. Through their collections of texts and author portraits, they could also link the past, present, and future, and even assist the transmission of their patrons’ souls, or at least their reputations, into posterity.

1. Hor. Epist. 2.1.214–218; Joseph. Vit. 363 (Titus’ autograph imprimatur), with Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.9.2, and Jer. De vir. ill. 13.1; Claudian: CIL 6.1710.

2. Trans. Frazer (1966), 20–21; see ní Mheallaigh (2008).

3. Domitius Marsus was an epigrammatist and elegist of the late first century BCE; Albinovanus Pedo wrote epigrams, elegies, and an epic-style Germanica in the early first century CE.

4. Nauta (2002), 327 n. 2.

5. For example, SHA Tac. 8.1; Prob. 2.1; Car. 11.3; Aurel. 1.7, 10; 8.1; 24.7.

6. Harris (1989), 228–229.

7. For example, König et al. (2013).

8. Robson (2013); see also Potts (2000).

9. For example, Whitmarsh (2001); Goldhill (2001).

10. Ath. 1.3b.

11. Cic. De or. 3. 137. See Hom. Il. 2.558; Od. 11.631.

12. Strabo 13.1.54; Ath. 1.3a, 5.214d–e; Plut. Sull. 26.

13. Burzachechi (1963); Nicolai (1987).

14. Though see Coqueugniot (2013) who questions this identification.

15. Gal. Commentary on Hippoc. Epid. III, 17(1).607 K.

16. Plin. HN 13.21.

17. Strabo 17.1.8.

18. Ath. 1.22d.

19. The early Ptolemies in particular all cultivated an image of learned patronage: Ptolemy I favored Euclid and Strato; Ptolemy II Philadelphus was a zoologist, and was reputed to have had the Pentateuch translated into Greek (see below); Ptolemy III Euergetes promoted the career of Eratosthenes; Ptolemy IV wrote a tragic play. See further, more generally, Chapter 13 below.

20. The Pentateuch: that is, the first five books of the Tanakh—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

21. Bartlett (1985), 20–23.

22. Plin. HN 30.4. Cf. Berossus, whose Greek Babylonica, which drew on Babylonian source material, was written for Antiochus I Soter around 290 BCE.

23. Alexandria: Plut. Caes. 49; cf. Sen. Tranq. 9.5; Cass. Dio 42.38; further destruction of the Brucheion district in 272 CE, according to Amm. Marc. 22.16.15. Rome: Gal. De loc. aff. 12–13.

24. Too (2010), 51–98, 173–188.

25. Suet. Claud. 42.

26. Hor. Epist. 2.1.156.

27. Isid. Etym. 6.5.1; Plut. Aem. 28 calls the two sons, Q. Fabius Maximus Aemilianus and P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus, φιλογραμματοῦντες. For the latter as patron: Polyb. 31.23–24.

28. Cic. Fin. 3.7–10.

29. Grilli (1962), fr. 8 (tragedy); 10 (comedy); 11, 13–15 (history); 12 (lyric poetry).

30. Sider (1990), 540, draws attention to “countless marginalia and commentaries in the manuscripts” at Herculaneum. For an overview of the library of the villa, see Sider (2005).

31. Ath. 1.3b; Mart. 12.3.

32. Note Suet. Iul. 56.7; cf. Nauta (2002), 121 with n. 99.

33. Bibliothecas Graecas Latinasque quas maximas posset publicare (Suet. Iul. 44); bibliothecas publicavit Pollio Graecas simul atque Latinas (Isid. Etym. 6.5.2); bibliotheca, quae prima in orbe ab Asinio Pollione ex manubiis publicata Romae est (Plin. HN 7.115); Asini Pollionis hoc Romae inventum, qui primus bibliothecam dicando ingenia hominum rem publicam fecit (ibid. 35.10).

34. Xen. Mem. 4.2.10 for the posturing book collector Euthydemus the handsome; Petronius, Sat. 48.

35. Hor. Epist. 1.3.15–20.

36. Ov. Tr. 3.1.63–64.

37. Catull. 95.8 and 36.1 for the luckless Annals of Volusius; Hor. Epist. 2.1.269–270. See also Farrell (2009).

38. Plin. HN 35.2.9.

39. See further Nicholls (2011).

40. Suet. Tib. 70.

41. Dio Chrys. Or. 37.8 (possibly the work of Favorinus in fact).

42. Ov. Tr. 3.1; Sen. Dial. 6.1.3. Cf. Cass. Dio 57.24.2–4; Tac. Ann. 4.34; Suet. Calig. 16.

43. Suet. Calig. 34.2.

44. Gell. NA 5.21.9.

45. Gell. NA 11.17.

46. Gell. NA 13.20.

47. Mart. 12, preface.

48. Gal. Lib. Propr. 2.21; cf. SHA Τyr. Trig. 31.10.

49. SEG 21.703.

50. Archaeological evidence shows as much, as does the anecdote that Tiberius intended to place a huge statue of Apollo Temenitos in a library at Rome: Suet. Tib. 74.

51. Suet. Aug. 29; Tac. Ann. 2.37.

52. Apul. Flor. 18.

53. Sid. Apoll. Ep. 9.14.2 (cf. 2.9.4, 4.8, 9.9); cf. Aur. Vict. Caes. 14.3; Cass. Dio 73.17; SHA Pert. 11; Alex. Sev. 35; Gord. 3.

54. Galen, Peri Alupias 21.

55. For an amplification of this idea, see Nicholls (2015). Network theory is well established in the fields of mathematics, sociology, and anthropology; the present volume demonstrates its increasing interest to scholars of the ancient world. For a useful “tutorial,” see Ruffini (2008), 8–40; note also Malkin et al. (2009), 1–8. Although in the case of ancient libraries, space and a paucity of data preclude the proper quantitative analysis that is at the core of the method, its terminology has value for considering how they functioned.

58. See Chapter 15 below.

59. CIL 3.607; cf. Plin. Ep. 1.8 on the slight popular appeal of libraries compared to that of gladiatorial shows.

60. Plin. Ep. 10.81.