MAP 5.1 Sites mentioned in the text (Map compiled by the author and produced by the Ancient World Mapping Center)

THE MANY HUNDREDS of monuments discovered across the ancient Near East since exploration began there possess a strong hold on the scholarly and public imagination. Part of the reason for this is monuments’ tendency to communicate to us in the present the nature of society in the past, although our ability to interpret accurately the original function and intent of monuments is by no means guaranteed. This chapter discusses a select number of monuments through the general framework of communications, that is, how scholars have interpreted these objects that communicated particular kinds of information to past audiences.

For reasons of quantity, this chapter does not undertake a comprehensive survey of Near Eastern monuments from a strictly defined region or period. Indeed, as we will see, the period of “use” of a monument continues well beyond the time it was constructed, in many cases even to the present, such that conventional chronological frameworks rapidly lose their relevance. I offer here a selective discussion of monumental art from a restricted number of times and places, chosen primarily by virtue of these contexts’ ability to highlight aspects of my theoretical understanding of how monuments operate in society and how scholars can best approach them intellectually.

The material included in this chapter ranges from western Anatolia through the Levant and Mesopotamia to the Zagros Mountains of western Iran, and from roughly 1500 to 600 (all dates are BCE), or the Near East’s Late Bronze and Iron Ages. Although an array of urban statuary and landscape monuments will appear, the focus will be on landscape monuments of the Hittite Empire of Anatolia (ca. 1400–1200), and the Neo-Assyrian Empire of northern Mesopotamia (934–605; see Map 5.1). As for the focus on sculptures, it is true that monumental statuary and architecture are frequently found side by side in scholarly literature, especially in surveys of Near Eastern artistic remains.1 Nevertheless, the inclusion of monumental buildings in this study would further adulterate a contribution of necessarily restricted scope, so the present analysis is limited to monumental sculpture alone.

MAP 5.1 Sites mentioned in the text (Map compiled by the author and produced by the Ancient World Mapping Center)

It is monuments’ most intriguing and counterintuitive quality that, although often designed and built to endure for long periods of time, their meaning can change rapidly—sometimes even overnight—depending on their physical, social, and political contexts.2 To make matters still more complicated, it is possible, even likely, that at any given time a monument will have not one but many meanings, what Henri Lefebvre referred to as a “horizon” of meanings.3 It is therefore of the utmost importance to appreciate how a monument fits into the network of meanings that constitutes society. Writing about monumental buildings, Henri Lefebvre says that if the meaning of a monument is to be found anywhere, it is not located within the monument itself. Rather, the meaning lies in the interaction between monuments and the individuals experiencing them, the activities that take place there and those that are not permitted, the ongoing interactions between thing and person.4 Elsewhere, I have suggested that a productive framework for understanding monumentality is a relational approach that recognizes the ongoing dialogue between monuments and their social matrix, as well as between monuments and the people engaging with these objects.5

This chapter is thus divided into two parts. The first describes some of the ways that monuments were designed and implemented for communicative ends, frequently to convey messages of political authority, especially as sanctioned or legitimated by divine favor—in short, the production of monuments. This ideological message is perhaps the analytical object most frequently sought by scholars.6 But the principle of relationality instructs us that the way monuments are used, appropriated, and modified, whether intentionally or otherwise, requires us also to consider the reception of monuments. Such an attempt forms the second part of the chapter. As objects in an ongoing social dialogue, monuments are never just messages communicated by their creators, but always messages in a ceaseless game of “broken telephone”—accidentally altered or deliberately subverted at each point along the line.

In a programmatic article in 1903, the art historian Alois Riegl described how certain objects or locales, such as the birthplace or grave of an individual later recognized as historically or culturally significant, became monuments long after their creation. Calling these monuments “unintentional,” Riegl distinguished them from standard monuments: large, permanent objects that are deliberately built for commemorative ends. Although Riegl’s distinction is valid, the ancient Near East was full of monuments that were deliberately designed as such, consciously constructed objects intended to communicate a particular message. To be sure, our vision of Near Eastern monumentality is distorted by a century and a half of scholarly fascination with these objects at the expense of more quotidian items. Nevertheless, it remains the case that monuments were a common component of ancient Near Eastern life. There are countless instances of monuments’ being erected by royalty and other élites able to do so. Here I analyze some of the ways that monuments were deployed to communicate the message of their creators, focusing primarily on the Hittites and the Assyrians.

The Hittite Empire was based out of their capital city Ḫattuša located north of the Kızılırmak River on the Anatolian plateau. Although their language was Indo-European, the Hittites used the Mesopotamian cuneiform writing system for most of their written documents.7 One significant exception, however, is the hieroglyphic inscriptions written in Luwian.8 These appear on urban and landscape monuments during the New Kingdom period, the late fifteenth to early twelfth centuries, especially in the second half of the thirteenth century during the reigns of Hattusili III, Tudhaliya IV, and Šuppiluliuma II, the last king of the Hittite Empire.9 The landscape monuments consist of figures carved in low relief on rock outcrops or low cliff faces across the mountainous plateau of central Anatolia (e.g., Fıraktin, Hatip, İmamkulu, Karabel; Figure 5.1). Occasionally, inscriptions are found in isolation (e.g., Suratkaya), but typically they accompany the reliefs, which depict ruling and divine figures in profile. A second, less common, form of Hittite monument consists of sacred pools constructed on top of productive natural springs (e.g., Yalburt, Eflatun Pınar; Figure 5.2). Yazılıkaya, an open-air rock-cut sanctuary located just over a kilometer northeast of the Hittite capital of Ḫattuša, may also have been the site of a spring in antiquity.10 In that case, this most famous of all Hittite monuments—depicting Hurrian gods and goddesses adopted by the Hittites in well-preserved array—may combine aspects of both major types of Hittite landscape monuments.11

FIGURE 5.1 Hittite rock relief at Fıraktın in the southeastern Anatolian plateau. The scene on the left shows Hattusili III (r. mid–13th century BCE) making a libation offering to the Storm God; the scene on the right shows Puduhepa, wife of Hattusili III, making a libation offering to the goddess Hepat. The individuals are identified by the Hieroglyphic Luwian signs above the figures. The continued inscription to the right of the relief further describes Puduhepa as “daughter of the Land of Kizzuwatna, beloved by the deity.”

(Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

FIGURE 5.2 Hittite sacred pool at the spring of Eflatun Pınar (Plato Spring) in the western Anatolian plateau (14th–13th century BCE). The reliefs of the north façade reach a height of 6 meters and consist of standing mountain gods, two large, seated figures underneath winged sun disks, and other figures. A large, winged sun disk stretches across the entire scene.

(Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The function of these monuments—what, exactly, they were designed to communicate—is the subject of debate. The most straightforward interpretation is that they were installed to portray the extent of Hittite territorial suzerainty as the empire expanded across the plateau from its heartland capital at Hattuša to peripheral areas in the east and west.12 But as the quantity of known monuments increases with additional discoveries, it becomes increasingly clear that many of them were built, not by Hittite rulers, but by local kings (Karabel, Hatip), princes (Suratkaya), or simply high-ranking officials (Taşcı A). As Claudia Glatz has argued, these monuments thus represent a struggle for power between central Hittite rulers and local dynasts. Rather than commemorate the successful stamp of Hittite power over territory, they assert—but do not vindicate—claims to territorial dominance that may not necessarily exist, emphasized particularly by their tendency to appear on important routes of communication.13

This interpretation, a case study of Elizabeth DeMarrais, Luis Jaime Castillo, and Timothy Earle’s argument that monuments materialize ideology, has been more systematically developed through the use of costly signaling theory (CST), a branch of communication theory developed in biology but also applied to evolutionary anthropology.14 According to CST, informative signals are communicated whenever such communication benefits both sender and recipient and the information being conveyed is not otherwise available to the recipient. In the case of politically inspired monuments, for example, rival rulers would benefit from knowing about each other’s wealth and resources. Furthermore, “cost [the investment of valuable resources, including labor, in monument construction] is the guarantor of the honesty of the information, allowing it to be trusted even by an audience that should otherwise be skeptical of the signal’s content.”15 It follows that Hittite monuments are thus to be understood as a medium through which rivals negotiated ongoing territorial disputes. The very existence of a large number of monuments with diverse authors indicates an unsettled political situation in which communications of strength via monument-building was required.16 Glatz has also applied CST to iconographically similar rock reliefs in the western Zagros Mountains that date to the Ur III and Old Babylonian periods (late third and early second millennium), when an unprecedented degree of centralization and territorial expansion occurred in southern Mesopotamian polities.17 CST implies that the raison d’être of landscape monuments was to communicate political strength, yet, as Glatz and Aimée Plourde themselves acknowledge, the communication of political messages is only one of many possible functions of Hittite landscape monuments.18 Noting the frequently attested phrase “Divine Road of the Earth” [(DINGIR) KAšKAL.KUR] in an inscription by Šuppiluliuma II in a stone chamber adjacent to a sacred pool in Ḫattuša,19 Ömür Harmanşah argues that sacred pool complexes built around natural springs, including landscape monuments in nonurban contexts such as Eflatun Pınar, Yalburt, and possibly Yazılıkaya,20 were “considered liminal spaces, entrances to the underworld, places where ritual communication with the dead ancestors could be established.”21 If this is the case, then we have a different order of communication entirely, one in which a political message may have been only one of the builders’ priorities, if at all. The lengthy military inscription of Tudhaliya IV at the Yalburt pool, for example, needs to be understood in the light of the monument’s possible chthonic associations.22 Likewise, the rock reliefs’ ability to communicate political signals of labor and material resources is compromised by the fact that many of them are not prominent, but rather require significant energy even to be located. The primary intended audience for at least some of the reliefs may have been the divine order, not humans. Furthermore, the reliefs’ striking natural settings, especially their association with springs and their high elevations, appear to be religiously charged.23 As most scholars acknowledge, and as suggested above, these monuments possess a cluster of meanings, at once mundane and divine, both statements communicating earthly power and attempts to communicate with powers beyond the earthly sphere.

The tradition of constructing landscape monuments did not end with the collapse of the Hittite Empire. On the contrary, construction continued across the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent during the Iron Age, from the late second millennium well into the first millennium, especially under the rulers of the Neo-Assyrian empire (ca. 934–605), who created the largest and most widespread corpus. Although their capital cities—Ashur, Nimrud, Khorsabad, and Nineveh—were located on or near the Tigris River in northeastern Iraq, the Assyrians built dozens of monuments in the peripheral regions of eastern Anatolia, northern Syria, and the Levant.24 To the Hittite rulers’ rock reliefs and occasional pool complex, the Assyrians added large, freestanding stelae inscribed with lengthy royal annalistic inscriptions. All of these monuments, whether reliefs or stelae, depict an Assyrian ruler accompanied by divine emblems. In total, about fifty Assyrian monuments in the periphery exist today. Historical records refer to another fifty or so.25

Assyrian peripheral monuments defy straightforward interpretation, partially because their production spanned three centuries and varying political contexts. One motive for many of them was to mark the territorial expansion of the Assyrian empire following annual military campaigns to neighboring regions.26 For the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II (883–859), Shalmaneser III (858–824), Tiglath-pileser III (744–727), and Sargon II (721–705), mapping the geographical locations of peripheral monuments through time indicates approximate Assyrian territorial control, and may suggest which outlying areas were viewed as the most important.27 As Ann Shafer has summarized, “over the three centuries of their production … the royal peripheral monuments acted as a consistent and effective tool for creating a powerful Assyrian presence on the periphery.”28

Later in the history of the empire, the function of peripheral monuments expanded from communicating boundaries to negotiating relationships between Assyria and its subjects. Three Assyrian stelae that are not strictly about territories and boundaries illustrate especially well how these monuments promulgated royal ideology. Two are from the city of Til Barsip (modern Tell Ahmar), capital of the conquered city-state of Bit-Adini, and one is from the site of Zincirli, capital of the conquered city-state of Sam’al.29 All three were erected by the Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon (680–669) shortly after he conquered Egypt in 671. They depict him standing above the kneeling figures of the recently captured crown prince of Egypt and the Sidonian king Abdi-Milkutti, who had rebelled against Assyria unsuccessfully in 677. At 3.5 meters in height, plus a meter-high base, these monuments were clearly designed to impress the viewer with the might of the Assyrian king, and with the inevitable futility of resistance.

Nonetheless, the Zincirli and Til Barsip stelae differ from one another in subtle iconographic ways. Among the many small discrepancies, the defeated kneeling rebels are significantly smaller on the Zincirli stele than on the Til Barsip stelae—their heads reach the height of Esarhaddon’s knees and waist, respectively—and thus they strain their heads more as they look up. Furthermore, on the Zincirli example, Esarhaddon holds leashes attached to rings in the captives’ lips. These leashes are absent on the Til Barsip examples (although these stelae are also more weathered). Barbara Porter interprets these differences politically: Zincirli, located in a remote valley at the base of the Amanus Mountains, was conquered late, and had frequently participated in anti-Assyrian coalitions; Til Barsip, on the Euphrates, was conquered early, and was converted into a major Assyrian administrative center, Kar-Shalmaneser, with concomitant blending of local and Assyrian politics and culture. The stelae at these two sites thus represent interactions with two different western audiences, one already conditioned to be receptive to Assyrian dominance, and one more prone to rebellion. In this light, it is clear that, while all peripheral monuments did indeed function to celebrate royal Assyrian authority, they were consciously designed to communicate subtly different messages to specific audiences.30

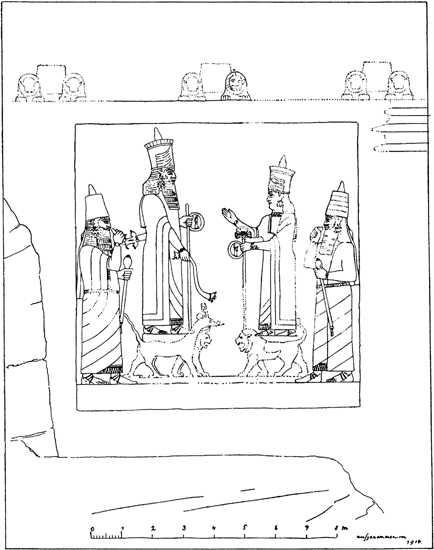

Assyrian landscape monuments, like their Hittite predecessors, were often located in remote locations that could be difficult to access. Some, like the several rock reliefs of divine figures in the small outdoor shrine at Karabur high in hills east of Antakya, have no inscription or distinguishing iconographic feature permitting a date or an unambiguous interpretation beyond ritual in the broadest sense.31 But references to landscape monuments in Assyrian texts and iconographic representations indicate that these monuments were both the subjects and the recipients of rituals involving animal sacrifice that clearly related to divinely sanctioned kingship.32 One example is the huge relief carved by Sennacherib (704–681) at Khinis, showing the king with Ashur and his wife Mulissu, the national gods of Assyria (Figure 5.3).33 This relief and its accompanying text, the so-called Bavian Inscription, stand at the head of the Khinis canal, Sennacherib’s most ambitious hydraulic engineering project.34 A massive aqueduct provided water for agricultural and urban activity in the Assyrian heartland.35 That the monument and its text proclaim the might and accomplishments of the king is self-evident, but the iconography is unusual among Assyrian rock reliefs in that it depicts, not just the king and divine symbols, but the king facing anthropomorphic figures of the deities. Sennacherib represents the gods in the same way as himself, possibly an act of self-deification.36

FIGURE 5.3 Large rock reliefs above the canal head at Khinis, carved by the Neo-Assyrian ruler Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BCE) and showing him with the Assyrian national deities Ashur and Mulissu.

(After Bachmann [1927], Abb. 8)

Perhaps the most striking Assyrian peripheral landscape monument is the series of reliefs and inscriptions carved into the rock at Birkleyn in eastern Turkey, at the source of the Dibni Çay, a tributary of the upper Tigris River. The visually striking gorge at this location harbors a number of caves, under which the Dibni Çay flows through a 900-meter tunnel carved into the limestone formation in the rocky landscape. Today the location is referred to as the “Source of the Tigris” or “Tigris Tunnel” (Figure 5.4a). In the Iron Age, it was visited by the Assyrian rulers Tiglath-pileser I (1114–1076) and Shalmaneser III (858–824), both of whom had their images and inscriptions carved into the rock.37 Although the location is “peripheral” from the perspective of the Assyrians, the Source of the Tigris monuments were by no means installed in a cultural vacuum. On the contrary, this landscape was a highly contested zone during the preceding Late Bronze Age.38

FIGURE 5.4A Neo-Assyrian reliefs at Birkleyn: (a) the cave system of the Dibni Çay, the so-called Source of the Tigris; (b) representations of Shalmaneser III’s (r. 858–824 BCE) actions at Birkleyn on the bronze gates of Balawat, a city in the Assyrian heartland: the tunnel and flowing river are shown, as well as the carving of reliefs, the caves, and preparations for ritual activities outside the caves.

(a: Photo courtesy of Andreas Schachner; b: King [1915], Plate LIX)

Hurrian, Urartian, and Syro-Anatolian kingdoms all had material interests in the resources located in this region of Turkey and had important centers located throughout. Upūmu, capital of the Hurrian kingdom of Šubria, was probably located just twenty kilometers from Birkleyn.39 By situating the monument near a subterranean water course, the Assyrians were playing on the Hittite practice of placing monuments at watery locations with chthonic associations. The Source of the Tigris monuments thus represents the Assyrian adoption and manipulation of local landscape practices to communicate their own rhetoric of kingship, replete with rituals taking place at the monuments themselves.40 Furthermore, the act of creating these monuments at Birkelyn was commemorated in the inscription on the Black Obelisk, a monument erected by Shalmaneser III in the Assyrian capital city of Nimrud, and portrayed on the famous gates at Tell Balawat (ancient Imgur-Enlil), another city in the Assyrian heartland.41 Band 10 of the repoussé door panels at Balawat shows the installation of the Source of the Tigris monuments in some detail, illustrating with great accuracy the caves, the flowing river, the tunnel, the reliefs, and an accompanying sacrificial ritual (Figure 5.4b).42 As Harmanşah writes, “while the acts of inscription at the Birkleyn site distributed the Assyrian king’s symbolic body into this frontier landscape, a liminal place, the representational monuments at the Assyrian urban core reincorporated the commemorative frontier performances of the remote landscapes of the north into the narratives of the state.”43

Despite the many monuments erected by the Assyrians, their art is best remembered for the hundreds of orthostats decorated in low relief that lined the walls of their palaces.44 These immense and complex relief programs have been the subject of analysis since Austen Henry Layard first brought them to light in the mid–nineteenth century. The most complete and familiar reliefs come from Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace at Nimrud, Sargon II’s palace at Khorsabad, Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace at Nineveh, and Ashurbanipal’s North Palace, also at Nineveh;45 the original palatial contexts of other collections of reliefs are less understood.46 Each corpus has its own particular emphases, such as the magical and ritual scenes of Ashurnasirpal, the long rows of courtiers and tribute bearers of Sargon, the large-scale landscapes and technological marvels—such as the quarrying and installation of colossal bull statues—of Sennacherib, and the lion hunt scenes of Ashurbanipal. All of the kings prominently displayed victorious battles and scenes of sieges. Over the course of time, narrative imagery increases, culminating in the elaborate and visually complex scene of the Battle of Til-Tuba, in which Ashurbanipal’s chase, capture, and decapitation of the defeated Elamite king Teumman amidst the chaos of battle are illustrated in great detail.

Nevertheless, the aesthetic style of the reliefs remained largely consistent over the 250 years that the reliefs were carved. The primary communicative goal had not changed: the glorification of the king as the divinely sanctioned embodiment of ideal kingship.47 The throne room of Ashurnasirpal’s palace at Nimrud expresses this message conspicuously. Irene Winter’s famous analysis of this room (1981) has shown that, not just the content of the reliefs, but also their placement on the walls and incorporation of the layout of the room, articulated unmistakably the rhetoric of the king as custodian of the natural order. For example, a scene showing the king and the sacred tree faced the viewer as he or she entered the room, and again as he or she turned to face the throne.

Assyrian palace reliefs also communicated more subtle messages beyond simply the overwhelming power and authority of the king. Because the intended audience of the reliefs was not only Assyrians but also visiting dignitaries and tribute bearers from regions that Assyria had turned into vassal states or conquered outright, the artisans were careful to depict foreigners distinctly, whether through clothing and physical appearance or through gesture and posture. By illustrating foreigners’ body language in a manner that violated Assyrian norms, the artists presented their violent fates as logical and inevitable, thereby encouraging to visitors the wisdom of conformity.48 In addition, the master artists who crafted the reliefs in collaboration with court scholars encoded messages in the non-narrative, emblematic elements of the reliefs. Though only a coterie may have understood these messages, they conveyed some of the philosophical views of Assyrian intellectuals, such as a fundamental kinship between animals and humans, expressed visually in their similar portrayals of anatomy; another is the association of scholars and craftsmen with mythical beings represented by Mischwesen, or figures mixing human and animal features.49 Such messages of foreigners’ alterity or mythological “codes” among the court’s elite scholars may be highly esoteric communications, but they were nevertheless as real a component of Assyrian palace reliefs as their straightforward attempt to legitimize the king.

The above discussion of Hittite and Neo-Assyrian landscape monuments and palace reliefs has concentrated on intent, what the producers of these objects wanted to communicate to a specific audience. As we have seen, identifying intended meaning is never as simplistic a process as the analyst might wish, for in every instance multiple communicative motivations can be isolated. But monuments’ multivocality is compounded exponentially by their varied reception over time and across cultures, a process exacerbated by their tendency to be constructed out of permanent materials. For example, at the time of their discovery Assyrian palace reliefs played a significant role in the culture of Victorian England, from the light they shed on the biblical narrative of Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah and the siege of the Judahite city of Lachish, to the part their acquisition played in the imperial interests of the day.50

One fascinating difference between production and reception lies in the physical treatment of monuments. For a number of reasons, monuments in the ancient Near East were often vandalized or destroyed outright.51 Following the sack of Nineveh in 612 by the Medes and the Babylonians, for example, the faces of the Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal were chiseled out of the reliefs from the city’s Southwest and North Palaces; only four examples of Sennacherib’s figure were left unmolested (Figure 5.5). In some instances, the conquerors shot arrows directly at the reliefs.52 Sennacherib had destroyed Babylon several decades prior to the fall of Nineveh, and the effacement of his image was an act of retribution. The removal of the king’s name from the surrounding text, however, suggests another, deeper motive. Depictions of the king were images, Akkadian ṣalmu, that were taken to be the king himself, more than simply representations of the individual in the Western sense of portraiture.53 The conquerors wished to put the king’s identity to death, and by removing the visual evidence of Assyrian power, the conquerors were removing the Assyrian Empire itself.

FIGURE 5.5 The famous Garden scene from the North Palace of Nineveh, showing the king Ashurbanipal (r. 668–630 BCE) and his wife Aššuršarrat lounging; the head of the defeated Elamite ruler Teumman dangles in a tree nearby. Note the obliteration of Ashurbanipal’s face and right hand, as well as damage to Aššuršarrat’s face, done following the sack of Nineveh in 612.

(British Museum, ME124920, AN32865001. Image courtesy of the British Museum)

The contemporary Syro-Anatolian culture—conquered by the expanding Neo-Assyrian Empire during the ninth and eighth centuries—conducted a related practice.54 Colossal royal statues that once stood in the gateways of their cities must also have had human-like significance, for they are often found buried or entombed in stone constructions above ground as one might treat a deceased person; the entombed statue at the Lion’s Gate at Malatya is a prominent example.55 Unfortunately, we have little information about the historical circumstances that prompted such burials. Other royal statues have been found smashed, as at Tell Tayinat and Carchemish.56 Some may have been decommissioned and buried after a change in dynasty, and others may have been destroyed by the conquering Assyrians. Whatever the circumstances, these Syro-Anatolian royal monuments met with a fate very different from what was intended when they were erected.

Abduction and geographical transfer is another example of how the meaning of monuments depends on time and place. This practice was common in the ancient Near East, and was used particularly as a tool for political power by expanding states over newly conquered territories.57 The palace reliefs of the Assyrians depict divine statues being paraded back into the imperial capitals, as in a scene from the reign of Tiglath-pileser III found in the Southwest Palace at Nimrud,58 and Syro-Anatolian statuary was discovered in Nebuchadnezzar II’s Northern Palace in Babylon.

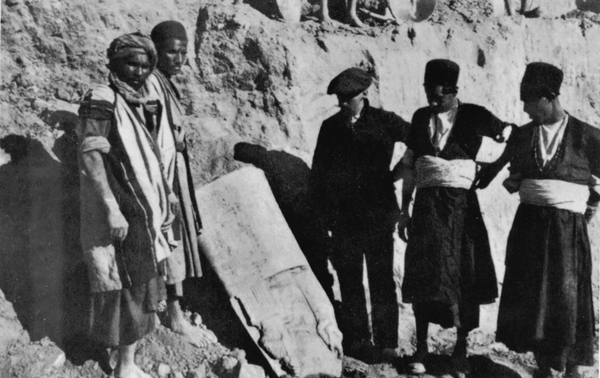

The most dramatic instance of statuary plunder is the large cache of Mesopotamian monuments discovered by French excavators at the Elamite site of Susa in southwestern Iran. The Elamite King Shutruk-Nahhunte I took them to the city in 1158.59 Included were the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin (r. 2254–2218) and the Code of Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750), two of the most important pieces of Mesopotamian statuary from any period (Figure 5.6). That they had been transported to Susa over 300 kilometers from the Mesopotamian site of Sippar is remarkable enough. Consider also that Naram-Sin’s Victory Stele must have been on display at Sippar for over a millennium before Shutruk-Nahhunte found it. (Unfortunately, shortcomings in the early excavations at Sippar and Susa have made it impossible to reconstruct both the monuments’ original locations in Sippar and their precise findspots in Susa.) Scholars debate whether Shutruk-Nahhunte handled the Victory Stele reverently and protectively, with damage being caused by one or more other, unknown agents, or whether he considered it captured booty; but the fact that Naram-Sin’s name was not removed from the stele would suggest the former.60 Either way, this monument, like the Code of Hammurabi and the other pieces absconded to Susa, had a long history of social memory far removed from Naram-Sin’s original intent.

FIGURE 5.6 The 1901 discovery of the Hammurabi stele by French excavators Gustave Jéquier and Jacques de Moran at the Elamite city of Susa, several hundred kilometers from its original home in the Mesopotamian city of Sippar.

(After Harper and Amiet [1992], Figure 45, with permission of Musée du Louvre)

Although many archaeologists have explored the concept of memory, only recently has it been applied as a theoretical tool by archaeologists working on monuments of ancient Anatolia.61 Felipe Rojas and Valeria Sergueenkova note that several monuments created by the Hittites were reused and reinterpreted in the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine periods in a variety of ways. Perhaps the most compelling example is the “throne” at Kızıldağ, a dizzying rocky outcrop atop a hill overlooking the Konya plain, and inscribed in Hieroglyphic Luwian by the “Great King” Hartapus. This striking monument is made all the more remarkable by the presence of five pairs of engraved footprints on the throne’s platform, accompanied by the Greek inscription “The priest Craterus, [son] of Hermocrates, jumped.” Apparently, this royal monument was converted to a site for sacred rituals during the Hellenistic or early Roman period, including rituals that may have endangered the life of the cultic performer.62

Harmanşah has larger disciplinary objectives, seeking to reorient archaeologists’ positivist treatment of landscape monuments to an archaeology of place, by which he means

a locality that is made meaningful for particular local communities. Places are deeply historical sites of cultural significance, memory, and belonging, while they are constituted and maintained by a spectrum of locally specific practices, past events, stratified material assemblages that are residues of those events, as well as bodily interactions with the physical environment.63

The methodological consequence of this stance is no longer to prioritize a monument’s original time of construction, but rather to see monuments as continually made and unmade, characterized by episodic cycles of incorporation by local communities. As Harmanşah’s evocative chapter-title describes it, “Rock reliefs are never finished.” A prime example is the İvriz spring, which was the venue for a monumental relief of Warpalawa, king of Tabal, in the eighth century BCE, but by the seventeenth century CE had become a place of healing and pilgrimage.64 Cases such as these are reminders of monuments’ tendency to be reused, reinscribed, and reinterpreted through time, accruing layers of meaning whose disentangling often can be frustratingly speculative.

This chapter has by no means exhausted the questions of how monuments were intended to communicate messages and how those messages were received and subsequently manipulated. It has not treated Riegl’s “unintentional” monuments, nor has it considered the problem of scale: just how large does something have to be before we can consider it a “monument”? Given the close iconographic association between Neo-Assyrian cylinder seals and the palace reliefs, for example, we might consider the seals every bit as monumental as the reliefs, despite the great difference in size.65 In that case, a discussion of Near Eastern monumental communication must expand considerably.

Whatever borders we set for our inquiry, we should remember the principle of relationality—monuments’ ongoing dialogue with the people viewing and experiencing them, and their place in society’s network of symbols and material culture. In this way we are able to appreciate the multiple and overlapping meanings that the Hittite and Neo-Assyrian sculptors communicated to their audience, whether that message was territorial holdings, royal power, divinely sanctioned authority, or participation in esoteric court intellectual life. Although the monumental statuary of the Near East during the Late Bronze and Iron Age was a rich and complex phenomenon, an appreciation of the reception of these monuments, together with their production—matters of ultimate effect as well as of immediate intent—offers a productive point of entry into this enduring part of the distant past.

1. For example, Frankfort (1996); Moortgat (1969).

2. As argued convincingly for both ancient and modern Chinese contexts by Wu (1995), (2005).

3. Lefebvre (1991), 222.

4. Lefebvre (1991), 224.

6. See, for example, many of the papers collected in Osborne (2014a); Burger and Rosenswig (2012); Thomas and Meyers (2012).

7. Bryce (1998) provides the historical background.

9. See Ehringhaus (2005) and Kohlmeyer (1983) for comprehensive surveys.

10. Harmanşah (2011), 635.

11. Alexander (1986); Bittel (1967); Seeher (2011).

12. Ehringhaus (2005), 119–120; Kohlmeyer (1983), 103; Seeher (2009).

13. Glatz (2009), 136.

14. DeMarrais et al. (1996). CST and biology: Maynard-Smith and Harper (2003). Anthropology: Bliege Bird and Smith (2005). See further Chapter 14 below.

15. Glatz and Plourde (2011), 35.

17. Börker-Klähn (1982); Debevoise (1942). The extent to which the Hittites were aware of the earlier Zagros exemplars is unclear.

18. Glatz (2014a); Glatz and Plourde (2011), 35.

20. Eflatun Pınar: Börker-Klähn (1975); Bachmann and Özenir (2004).

21. Harmanşah (2011), 636.

23. Ullmann (2010); Stokkel (2005), but cf. Glatz (2014b), 129.

25. Shafer (2007), 133.

26. Shafer (2007), 134–136.

27. Left aside here are the complicated issues surrounding Assyrian territory and territoriality, especially the degree to which conquered lands were incorporated, and in what ways: see Postgate (1992); Liverani (1988); Parker (2001), (2013). For an overview of territoriality in early complex societies, see Osborne and VanValkenburgh (2013).

28. Shafer (2007), 136.

29. Til Barsip: Thureau-Dangin and Dunand (1936), 151, 155. Zincirli: Luschan (1893), 10.

30. Porter (2000a), 175–176.

32. Shafer (2007), 141–144.

33. Jacobsen and Lloyd (1935), 44–49; Börker-Klähn (1982), 206–208.

34. Jacobsen and Lloyd (1935), 36–39; Bagg (2000), 347–354.

35. Jacobsen and Lloyd (1935); Ur (2005).

37. Schachner (2006), (2009); Shafer (2007); Russel (1986); Waltham (1976); Harmanşah (2007).

38. Harmanşah (2007), 189.

39. Kessler (1995), 57.

41. Nimrud: Grayson (1996), 65.

42. King (1915), pl. LIX.

43. Harmanşah (2007), 195.

45. Nimrud: Meuszyński (1981); Paley and Sobolewski (1987), (1992); Russell (1998). Khorsabad: Loud (1936); Albenda (1986). Southwest Palace at Nineveh: Barnett et al. (1998). North Palace at Nineveh: Barnett (1976).

46. See, for example, Barnett and Falkner (1962).

47. Collins (2009), 17.

50. Invasion: 2 Kings. chapters 18–19. Imperialism: Larsen (1996).

52. May (2012b), 188–189.

53. Bahrani (2003), 123–127, 151–152.

54. Orthmann (1971); Gilibert (2011); Ussishkin (1989).

55. Osborne (2014c). Malatya: Delaporte (1940).

56. Tell Tayinat: Gelb (1939), 39. Carchemish: Woolley (1952), 192–199.

57. Schaudig (2012); Holloway (2002), 123–144; Cogan (1974), 22–34; Johnson (2011); Bahrani (2003), 174–184.

58. Barnett and Falkner (1962), pl. XCII.

60. Other agents: Harper and Amiet (1992), 161, 166, with Westenholz (2012), 98. Booty: Bahrani (2003), 164. No damnatio memoriae: Feldman (2009), 44.

61. See Alcock (2002) and Bradley (2002); Harmanşah (2014b, 2015a, 2015b).

62. Rojas and Sergueenkova (2014).

63. Harmanşah (2015a), 18.

64. Harmanşah (2015a), 136–141, 152–153.