Kenneth W. Harl

THIS CHAPTER DISCUSSES coins as a medium of communication as well as an economic instrument that facilitated—and, in my opinion, assured—the exchange and movement of goods and services across the Roman Empire. It is important to realize that coins function in several ways: through iconography (or symbolism), through circulation, and as a store of value. Historians have focused on the first aspect, debating the content of the messages on coins. However, discussion of the other two aspects, circulation and value, has been left to numismatists, who have diligently researched the second and largely ignored the third. This chapter reviews all three aspects, but concentrates on the third, concluding with a discussion of fiduciary coins of the Roman Empire during the third and early fourth centuries CE.

Some other ancient monetary instruments are ignored here. Bullion could both circulate and serve as a store of value, but it did not bear images as opposed to markings. Even as a store of value, it differed from coinage because its value was intrinsic and measured by weight, whereas the value given to coins was conventional, and measured according to number and amount. As a consequence, coins were more convenient as a means of payment or exchange. A fortiori, coinage differed from natural currencies such as cattle and cowrie shells. These could not bear images, let alone be valued by weight or amount as opposed to number; hence they were not only inconvenient, but also unreliable because of their lack of uniformity. Finally, coinage differed from ancient monies of account; that is, records of amounts of bullion (mainly silver) that were pledged in standard amounts such as the talents, mnae, and shekels of the Fertile Crescent, and the talents, minas, and drachmae of the Greeks. This kind of money did not bear images either, and, although it commonly functioned as a medium of exchange, it served less often as a means of paying taxes and tribute. Despite its convenience and uniformity, it was not universally acceptable. It met the needs of merchant houses more than those of smaller enterprises or most individuals. Coins, in short, were the most serviceable kind of money.

Among the aspects of coinage, communication of messages is the one most often studied. Coins with their legends (inscriptions) and types (images) communicated many different types of messages, be they political, religious, cultural, or social. Scholarly debate has centered on this role of coins ever since Hugo Jones raised doubts over coins as a source of information, ironically in an essay in honor of the noted numismatist Harold Mattingly. Jones despaired of interpreting coin types and legends because, in his opinion: “In the absence of any allusion to the matter in ancient literature, one can judge only on grounds of general probability.”1

In response, numismatists and historians have debated how various classes of people in the Greek or Roman world comprehended coin types. They have combed the literary and epigraphic sources for references to the intelligibility or comprehension of coin types.2 Too often, they have advocated one of two positions, either extolling or dismissing coins as a significant medium. Today the debate lies between these two extremes. Among those upholding coins as a medium communicating messages, none would advocate that even the most overt types celebrating imperial victories were propaganda in a modern sense. Roman coin types and legends were far removed from, say, Leni Riefenstahl’s movie Triumph of the Will (1934).

Instead, coin types and legends conformed to other artistic conventions and presented traditional values with a spin to the emperor’s benefit. In his book The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, Paul Zanker has masterfully placed coins within the context of other media communicating such messages.3 Anyone who has walked down the marble street of Perge through the Hellenistic Gate remodeled by the patroness Plancia Magna (Figure 16.1), 4or past the Sebasteion at Aphrodisias,5 is aware of how many public images and inscriptions assaulted a Roman’s senses every day. Coins were miniature versions of these media of communication. Pergamum, for example, issued a series of medallion-sized bronze coins depicting the visit of the Emperor Caracalla to its Asclepieion in 214 CE (Figures 16.2–3).6 Each reverse type has been taken from a panel of a relief sculpture narrating his visit. The impact of this Pergamene relief on the viewer would have been comparable to that of the frescoes depicting the cycle of Rama on the surrounding temenos walls of Buddhist sanctuaries in Thailand. The coins reminded the beholder of the grander relief.

The perception of messages by the viewers is still subject to debate. Recent efforts to quantify the types of messages disseminated on imperial coins, or to organize messages according to the specific audiences targeted, are far from conclusive.7 Nonetheless, there is hardly cause to doubt the intention of the imperial government in disseminating messages on coins, even if the public misunderstood or ignored them. Coins, along with other media, did convey news and cultural values, if not propaganda in the modern sense.

More important for the topic of communication, I suggest, is the wide circulation of coins, especially during Rome’s imperial peace.8 Circulation involves two factors, space and time. Distance is easily documented. Currently, numismatists each year publish reports of coin hoards, as well as formidable volumes cataloguing coins found in excavations. Coins were often carried far from their place of origin, so that they are an essential source for regional or long distance trade. Because later Roman imperial coins carried mint marks, finds of such coins permit conclusions about how well the provinces were supplied with money.9 Coins found beyond the imperial frontiers, notably in Germany (Figures 16.4–5) and India (Figure 16.6), document the extent of Roman commerce as well as the types of Roman coins that were preferred in foreign markets.10

Circulation also involves time: this aspect of the medium is often forgotten in discussions of coins in the next two roles to be discussed, namely iconography and value. Coins, even those struck in silver or gold, could circulate for very long periods, a fact affecting our understanding of money supply.11 By counting surviving dies among a coin population, numismatists have employed probability formulae to calculate total dies, and then they have estimated production based on the assumption that 20,000 to 40,000 coins were struck from a single obverse die.12 These figures, however, even if valid, are not indices of the money supply, because older coins circulated for a long time. Hence, any estimates of the number of coins struck based on die studies for any period are not a secure guide to total money supply.

This point can be illustrated by two examples. First, in my own collection, there are three unpublished silver coins bearing countermarks with the monogram of Vespasian (69–79), the imperial candidate of the eastern legions in 69 CE, the “Year of the Four Emperors.” A countermark is applied to an existing coin by striking it with a small engraved punch die; this method allows for rapid stamping of coins. In 74–79, Roman authorities at Ephesus ordered the countermarking of older silver coins in the name of the Emperor Vespasian.13 Many of these comprised denarii of earlier emperors. What is significant are the large numbers of Republican and provincial silver coins that were still in circulation when the countermarking was ordered. My collection includes two unpublished denarii of the Roman Republic countermarked in this way: one was struck around 86 BCE, the other was minted at Ephesus in 49 BCE on orders of the Optimate consuls L. Cornelius Lentulus and C. Claudius Marcellus (Figures 16.7–8).14 No less notable is a large silver cistophorus (equivalent to three Roman denarii) struck at Ephesus to celebrate the wedding of Mark Antony and Octavia in 39 BCE (Figure 16.9).15 All three coins were between 100 and 150 years old, and had lost between 11% and 15% of their weight, when they were revalidated for use by the countermark of Vespasian.16 Such countermarked denarii probably circulated for another fifty years until they were withdrawn from circulation and recoined by Trajan in 107.17 Some cistophori so countermarked circulated even longer, because they were overstruck during the recoinage under Hadrian in 123.18 This same circulation pattern is confirmed by coin finds from Pompeii, where at the time of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius (79 CE), over half the silver denarii in circulation were Republican denarii 100 to 250 years old.19

Token or fiduciary coins circulated even longer, for between three and four generations. A cache of nearly 4,000 Roman bronze coins (aes) was recovered from a shipwreck in the Garonne River that occurred in 160 CE. Recent coins were a tiny percentage of this cache; nearly half the coins were twenty to forty years old, another third sixty years old, and a sixth over a century old.20

In short, coins were ubiquitous in the Roman world.21 There is no reason to conclude, as Moses Finley did, that, “Money was coin and nothing else, and shortage of coins was chronic, both in total numbers and availability of preferred types or denominations.”22 The wide circulation of coins in time and space invalidates arguments for a dearth of coins in the Roman Empire.23

THE THIRD AND foremost aspect of coins is as a store of value: coins are money. Unlike the other two aspects, this one has been underestimated. In his Ancient Economy, Finley assigned coins a minimal part in what many scholars would dub today the underdeveloped economies of Greek cities and the Roman Empire:

The Greek passion, and for beautiful coins at that, was not shared by many of their most advanced neighbors, Phoenicians, Egyptians, Etruscans, Romans, because it was essentially a political phenomenon, “a piece of local vanity, patriotism or advertisement with no far-reaching importance” (the Near Eastern world got along perfectly well for millennia, even in its extensive trade, with metallic currency exchanged by weight, without coining their metal). Hence, the insistence, with the important exception of Athens, on artistic coins, economically a nonsense (no money-changer gave a better rate for a four-drachma Syracusan coin because it was signed by Euainetos).24

I sense here that Finley regarded coins as a nuisance. Even so, many historians have followed his lead. Those interested in the social history of Archaic and Classical Greece have envisioned a primitive economy as a background for Herodotus or Pindar.25 In the case of imperial Rome, Finley’s successors seldom discuss coins as money, for they reduce them to fiscal instruments that benefitted only the imperial government and facilitated the collection of taxes.26 Coins and markets are sidestepped.

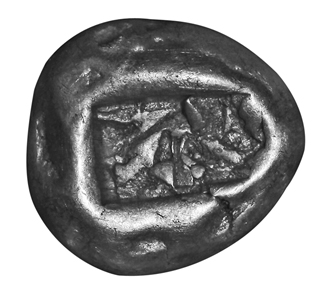

Finley admits bewilderment about why Athenian tetradrachmae, “owls,” were preferred in the Aegean world and Egypt. The reason is that the types of ancient coins made them a reliable store of value. Even the types of the earliest coins, those minted by the Lydian and Persian kings, communicated value (Figure 16.10). The Persian gold coin, bearing the portrait of King Darius, was dubbed by the Greeks a daric, which became the generic name of any gold coin. Hence, the first gold staters of King Philip II of Macedon (359–336), destined to displace the Persian gold coin, were initially called darekoi philippeioi (Figure 16.11).27 In the Classical period, trade coins minted by Aegina, Corinth, and Athens were recognized and traded according to their types: turtles, colts, and owls (Figures 16.12–13). The value of coins of Hellenistic kings was also reckoned by type, especially gold staters and silver tetradrachmae struck in the name of Alexander the Great (and carrying the heads of Athena and of Heracles, respectively: Figures 16.14–15), or the tetradrachmae bearing the posthumous portrait of Alexander minted by Lysimachus (Figure 16.16).28 All these coins were widely traded and imitated down to the Roman period.

Designating a coin’s value by its type was a Roman practice, too. Tacitus, writing early in the reign of Trajan (98–117 CE), notes how Germans preferred the Republican denarii, nicknamed bigati and serrati, over imperial coins (Figures 16.4–5 above).29 In the markets of the Near East, the silver tetradrachma, originally of Tyre, bearing a striding eagle on the reverse, was long preferred as a coin “of good silver with the Tyrian stamp” (Figure 16.17).30 In the late second and third centuries CE, the vast quantities of fractional bronze and copper coins minted by Greek cities of the Roman East illustrate this point. Often obverse portraits on these bronze coins designated value denominated in assaria, the Greek equivalent of the Roman asses (sixteen to eighteen of which were reckoned to the silver denarius). The largest coins of six assaria carried a portrait of the emperor; the four-assaria piece one of the empress or the Caesar; the three-assaria often a portrait of the Roman Senate (hiera synkletos); and lesser denominations, those of the city’s demos (assembly), boule (council), tutelary divinities, or eponymous heroes (Figures 16.18–21).31 The convention was so widespread that cities in Asia Minor often shared the same obverse dies bearing standardized portraits and cut by workshops of professional engravers operating in major cities. These obverse dies were matched with reverse dies bearing types relevant to each city.32

Such communication of a coin’s value continues to this day. Anyone who has negotiated Krugerrands, Napoleon 40-franc pieces, and British sovereigns knows that these coins, all recognized by their types, have retained their value over long periods. The most striking example is the Austrian thaler struck in the name of Maria Theresa and dated to 1780.33 This coin is the modern counterpart to the Athenian tetradrachma of the fifth century BCE. It is still an international trade coin, struck by the mint of Vienna, that circulates in East Africa and the Middle East. Since 1936, Rome, Paris, Brussels, London, and Bombay have also minted these thalers. At least 389 million have been struck at Vienna and other Hapsburg mints, but the number should be more than doubled to 800 million when all those struck outside of Austria are included. Each thaler is just under three-quarters of an ounce of pure silver, and carries the portrait of the empress on the obverse and a baroque coat of arms on the reverse.34 The decorative types and the date 1780 convey the coin’s value. In Aden, merchants known as Shroffs have long acquired these thalers and resold them to large Arab trading and banking firms.35 The firms export them to ports along the Red Sea for purchase of hides, skins, coffee, incense, and honey. Clever speculators profit further by buying up thalers at lower prices in the hot season between May to September when sales go down and demand for silver falls. In the same fashion, Athenian tetradrachmae (Figure 16.13 above), and Roman imperial denarii (Figure 16.6 above) circulated in the markets of Arabia Felix and inspired local imitations of favored trade coins.36

The Romans, too, employed value marks on their coins. These were first applied to copper or bronze coins. Syracuse so marked its fractional copper currency in the late Classical era.37 The Roman Republic utilized value marks and types together to designate its token bronze currency.38 The principal denomination was the as, a proxy piece representing a pound of bronze; it carried the head of Janus on the obverse, and on the reverse the prow with a prominent value mark (Figure 16.22). These types of the as were fondly remembered in the imperial age when tossing coins with “heads” (capita) or “ships” (naves).39 Twice, the Republic added value marks on the silver denarius; first after a debasement in 213–212 BCE (Figures 16.23–25), and second after the retariffing of the denarius upward from ten to sixteen asses in 141 (Figure 16.26).40

In addition, many Greek cities in the Roman East employed value marks on their bronze coins, which were exchanged against imperial silver coins (Figures 16.27–28). The rates of exchange changed with each debasement of the imperial silver antoninianus (or double denarius piece) between 238 and 260 CE.41 In the 250s, cities on the Pamphylian littoral, notably Aspendus, Attaleia, Perge, and Side, countermarked their older coins with marks of value in assaria so that each coin’s value was increased by one-third, one-half, or even double its original face value.42 These older coins circulated at par with the coins struck on the same weight standard but valued at the higher tariff after 255. In 274, when the Emperor Aurelian conducted the first currency reform of imperial money in fifty years, cities in Asia Minor responded by again countermarking their bronze coins.43 They devalued them, restoring them to their value prior to 255. At Side, many older, heavy coins struck between the reigns of Septimius Severus (193–211) and Valerian (253–260) had most likely circulated at values of ten assaria or higher in the inflationary period of the 250s and 260s. In 274, these coins were revalued downwards by countermarking with a value mark of epsilon denoting five assaria (Figure 16.29). Many light-weight ten-assaria pieces, which had been introduced to replace the heavy-weight five-assaria denomination in 255, were also countermarked as five-assaria pieces (Figure 16.30). Often the original mark of iota is still legible beneath the epsilon countermark (Figure 16.31).44 Side was one of several cities that conducted a particularly thorough countermarking in 274, thereby bringing the bronze currency back to its original value before the price surges of the 250s and 260s.

Officials of the Roman Empire inherited from Greek cities another means for informing the public of the value of its coins. This was the publication of decrees laying down regulations for exchange rates and fair prices enforced by market officials called epimeletai or curatores. The earliest, and one of the best preserved, is from Pergamum in the reign of Hadrian (117–138). In this imperial edict, we learn that disputes over exchange rates between the imperial silver denarius and local bronze coins (assaria) in the fish market forced a clarification of rates and prices.45 At Ephesus, market wardens posted bread prices prominently on the gate of Augustus and Maecenas for all to see as they entered the commercial market.46 Edicts from Cyzicus, Pisidian Antioch, and Mylasa regulated the value of coins to ensure fair pricing.47

LET US NOW turn to two of the most controversial coins of the later Roman Empire, the silver-clad fiduciary coins of Aurelian in 274, and of Diocletian in 293 (Figures 16.32–35). In issuing these, the imperial authorities employed all three means of communication to inform the public of the coins’ value: type, value-marks, and regulation. The significance of the value-marks on these coins has been overlooked or misunderstood by scholars who have dismissed the coins as the debased currency of the Dominate.48 European scholars writing in German during the 1920s and 1930s created a vision of late third-century coinage by making comparisons between the hyperinflation of the Great Depression and price surges and debasement in ancient Rome.49 Later scholars have posited that the Late Roman imperial government returned to a natural economy (Naturwirtschaft), levying taxes in kind, collecting taxes in gold coins treated as bullion, and dumping on the public bronze coins with a deceptive silver coating.50 Finley wrote: “Indeed, the time came, early in the Roman Empire, when the emperors could not resist taking advantage of their power and their coining monopoly to enrich themselves by debasing the coinage, a procedure that hardly contributed to healthy coin circulation.”51 Such a conclusion misses the point that later Roman coins had value. The fact is borne out by the widespread hoarding of them.

Late Roman coins were fiduciary money. For example, the denominations introduced by Aurelian and Diocletian used type- and value-marks to indicate each coin’s value, plus control-marks indicating the series, mint, and officina (or workshop) within the mint. All these signs communicated the conventional, as opposed to intrinsic, value of the coin. To fail to see this act of communication between coin issuer and coin user, and then between one user and another, is to miss the point that coins are a medium of communication rather than merely a manufactured quantity of metal. The ancient public knew better, and refused to reject fiduciary coinage on principle. Their concern was not the basis of the coinage, but price inflation.

The Roman government manipulated the coinage with corresponding confidence. In 238–270, successive emperors rapidly debased the silver currency, based on an antoninianus or double denarius (designated by the radiate portrait of the emperor). In 274, Aurelian replaced this debased silver currency with a silver-coated fiduciary coin, the aurelianianus, tariffed at five denarii communes (a money of account used instead of coined denarii). The new coin was of improved manufacture and silver content. On the obverse, it carries the radiate imperial portrait and, on the reverse, clear value-marks XXI or KA (= 20 sestertii), or a denomination of 5 d.c. (Figures 16.32–33 above).52 Even though we have almost no documentary records for the period from 274 to 293 when this coin was in circulation, hoards nonetheless indicate that it displaced the older money, and apparently proved a success.

In 293, the Emperor Diocletian enacted an even more ambitious currency reform, replacing all the money in circulation with a new currency for the entire empire. He, too, based his currency on a fiduciary coin, the nummus (often misnamed “follis” in the older scholarly literature), with three times the weight and over twice the silver content of the aurelianianus. The nummus carries a distinct laureate obverse portrait of the Tetrarchs and the new reverse type GENIO POPVLI ROMANI. Nummi are also sometimes marked with XXI or K/V, designating the coin as valued at 1 = 20 sestertii and 20 sestertii = 5 d.c. (Figures 16.34–35 above).53 Diocletian’s aim was to halt price inflation, which, he complained, had reduced the value of soldiers’ pay.54

Thanks to these steps, the imperial government paid its fiscal obligations in silver-clad fiduciary coins for about a century. Emperors had already employed a similar provincial fiduciary currency in Egypt, where wheat prices held stable for centuries.55 All these imperial fiduciary silver-clad coins were used to meet tax obligations, and they could also be exchanged against gold coins.56 The coins were valid for all debts, public and private. The Roman government had done what the United States government would do when it abandoned the gold standard in 1933, and detached the dollar from silver in 1964 and 1968.

In the late fourth century, the government continued its work. In 362, the Emperor Julian recalled, melted down, and restruck older billon (alloyed silver) coins as new currency based on a silver-clad maiorina that approximated Diocletian’s nummus (Figure 16.36). In the process, the number of mints and officinae was halved, suggesting that Julian also aimed to bring down prices by lowering the number of coins in circulation.57 Certainly, in 371 the emperors Valentinian I and Valens announced that they were reducing the number of fiduciary coins in circulation in order to bring down prices and promote exchange of goods in the market.58 For comparison, we may note a much earlier instance during the Tetrarchy where we even know the response to such fiduciary coins. When vendors and consumers refused to accept the nummus at the value officially set for it, the Tetrarchs responded by raising its notational value. In early 301, the nummus was probably circulating at a value of 12½ d.c., and this was then doubled by a monetary edict issued on September 1, 301, a copy of which has been uncovered in the excavations at Aphrodisias.59

When revaluation failed to check price rises, the Tetrarchs responded in more ambitious fashion. In November or early December 301, they issued regulations known as the “Edict of Maximum Prices,” and posted it in the markets of thousands of cities.60 Since this price edict could not have been read aloud—even its prologue was far too long for that—the Tetrarchs ordered the regulations to be inscribed in stone and erected in public places. Copies have survived on the walls of the tholos in the central agora of Aezani and on the back of the bouleuterion of Stratonicea overlooking an axial street.61

These regulations appeared in both Greek and Latin, and all prices and wages were quoted in denarius communis, a unit of account by which everyone could reckon the value of their coins. As Sture Bolin first noted, the reckoning of prices was based on multiples of two and five—a reckoning that dated from 141 BCE when the denarius was revalued at 16 asses.62 All the prices had to be converted into specific coins, notably the silver-coated nummus that was originally issued as a fiat coin of 5 d.c. (Figures 16.34–35 above), and its radiate fraction of 2 d.c. (Figure 16.37). In the price edict, these two denominations were worth 25 d.c. and perhaps 10 d.c., respectively.

How did the price edict work? Market officials referred to published copies when they settled marketplace disputes. The stated prices and wages set limits according to which officials and litigants adjusted prices, wages, quality of goods, and other issues. Every day in every market across three continents, in an empire of some 60 million people, a colossal if mundane commercial discourse took place—an all-important one tied to necessities. By this edict, the Tetrarchs communicated to their subjects the value of imperial money, but the public, too, had a means to communicate its reaction. Lactantius, who despised the Tetrarchs as persecutors of Christians, noted that vendors withdrew goods;63 they and consumers widely ignored the regulations and engaged in a black market. Within months, if Lactantius is to be believed, the Tetrarchs rescinded the edict, thereby allowing the nummus, tariffed at 25 d.c., to be exchanged according to the prices dictated by the market.64 The market thus had won. Prices and wages stabilized, and the value of nummus at 25 d.c. lasted at least until 313, when civil wars and debasements of the coin initiated by Constantine generated new price surges (Figures 16.38–39).65 In 321–324, Licinius, too, responded to the market by lowering the official value of his debased nummus to 12½ d.c. in a move to roll back prices (Figure 16.40).

After 301, the imperial government continued to communicate the value of its money in edicts, several of which are preserved in the Theodosian Code. Most impressive of these later edicts is one of 354 in which the Emperor Constantius II (337–361) recalled obsolete and debased coins, along with coins of the usurper Magnentius (350–353), and imitations and counterfeits.66 As with the price edict of the Tetrarchs, the market influenced his decision. Vendors and customers discounted or rejected these coins, and the emperor had to eliminate them in preparation for issuing a new set of values for the accepted coins. Such dialogue between government and markets continued into the Byzantine age, when the emperors Anastasius (491–518) and Justinian (527–565) reformed the base-metal copper coinage, based on a follis of 40 nummiae, to ensure price stability.67

All this material—a massive fiduciary coinage, recoinage affecting tens of millions of people, commercial regulations covering the entire Mediterranean basin—furnishes evidence for an intercontinental system of communication that invites comparison with early modern Europe or even the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As economic historians have noted, a massive fiduciary coinage came into existence in the United States only in the twentieth century.68 As for the recoinage ordered by Diocletian, it was perhaps the largest such measure until the nineteenth century.69 There is certainly no measure comparable to the Edict of Maximum Prices until the national economic regulations of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and even these regulations affected only advanced nations in Europe. In Italy, the center of the Roman Empire, comparable regulations do not predate the nineteenth century.

THE ROMAN SYSTEM could not exist in the abstract, nor could it exist only in a commercial sense. Currency and regulation on this scale require an economy to match, with forms of communication described by Taco Terpstra in Chapter 3 above. Communication through coins was thus both routine and indispensable. It facilitated the exchange of goods and services, and with it, the prosperity of the Roman world. It is absurd to regard coinage merely as an expedient for paying soldiers and officials.

In the Roman Empire, coins and markets went together. The market was where the imperial government and Roman public communicated about, and through, a currency that consisted of coins. The market was where currency had to be used, and it was where currency was sometimes found wanting. The market was not only where goods and services were bought and sold, but also where many taxes were paid.70 In a world without such financial instruments as bills of exchange, let alone paper money, the market was where coins predominated.

The conclusions put forward here about the coins of imperial Rome should also apply to other periods and other economies of the ancient world. There is a wealth of information in the coins themselves and in relevant regulations from the Archaic Greek through Byzantine ages, as well as a wealth of communicative relationships to be explored. It is apt, therefore, to close with a remark from Herodotus, who grasped the principle when he says that the Lydians struck the first gold and silver coins and so invented the market.71 Coins and markets went together. The Roman contribution, which was a fiduciary coinage on a grand scale, was an important episode in a history that is still unfolding.

1. Jones (1956), 14.

2. Harl (1987), 31–37, cites the earlier scholarship on the debate. The most significant new contributions are the essays in Howgego, Heuchert, and Burnett (2005), together with Noreña (2001); (2011), 190–200. Wallace-Hadrill (1986) offers judicious cautions about numismatic iconography. For reservations about the speed and ease of transmitting coin images, see Wolters (2003); (2006).

3. Zanker (1988). For comparable study on the iconography of later Roman coins, see Hedlund (2008).

4. Boatwright (1991).

5. See Smith (1987) for the reliefs now on display in correct sequence in the Archaeological Museum at Geyre.

6. Harl (1987), 55–58, with plates 23–24.

7. Noreña (2011), 1–199, 326–359, and app. 1–10, makes a statistical analysis of the frequency of personifications by type based on 180,000 specimens in published hoards. These data are not a reliable guide to the number of coins originally struck, and thus not a sure means of counting the messages in circulation. A die study alone might provide reliable statistics (but is impossible, given the numbers of surviving imperial coins). Noreña’s identification of personifications as imperial virtues and imperial benefits overlooks the religious aspects of what are goddesses, and often specific cult statues, plus sacrificial scenes.

8. For the wide circulation of the Roman silver denarius, see Howgego (1994); Harl (1996), 231–249. For circulation of imperial bronze coins in the West, see Hobley (1998), 138–140; Kemmers (2009), 152–155. For civic and provincial currencies in the eastern provinces, see Harl (1987), 12–20; (1996), 97–124.

9. Fulford (1978); cf. Greene (1986), 54–59. For a model study of coin circulation in the provinces, see Fitz (1978).

10. For finds in India, see Turner (1989). The finds from Germania are published in FDA. See further, Wheeler (1954), 63–68; Harl (1996), 292–313.

11. Duncan-Jones (1996), 163–168, and table 11, argues for an annual production of 22 million denarii between 64 and 235 CE. Silver and gold coins were subject to recall and recoinage whenever the standard was lowered; see Harl (1996), 11–16, 125–136. Whatever the validity of his method, Duncan-Jones’ estimates of 443 million denarii produced under Antoninus Pius and 532 million denarii under Septimius Severus reflect major recoinages in these reigns.

12. Carter (1983). For the technology of striking coins, see Sellwood (1963), whose estimate of 11,500 to 20,000 coins per obverse die is now considered too low. Kinns (1983) estimates 40,000 coins per obverse die; Crawford (1974), 694–697 estimates 30,000. Buttrey (1993), (1994) expresses reservations about these statistical methods. Responses to Buttrey: de Callataÿ (1995); Lockyear (1999).

13. Howgego (1985), no. 839.

14. Crawford (1974), 365, no. 350B, and 462, no. 445/3b, respectively, for types.

15. RPC I, p. 377, no. 2201 = Syd. 119 for the types. For countermark, see Howgego (1985), no. 840. Discussion by Thiron (1963), and Sutherland (1964).

16. This amount of loss is consistent with the calculation of a coin’s weight loss due to circulation by Duncan-Jones (1987).

17. Harl (1996), 92, 107.

18. Note Classical Numismatic Group, Auction 70 (September 21, 2005), no. 1001: cistophorus of Mark Antony and Octavia with the countermark of Vespasian overstruck for Hadrian at Sardis. For the type, see Metcalf (1980), type 47 (new dies).

19. Breglia (1950), with discussion by Harl (1996), 16–18; Duncan-Jones (2003).

20. Harl (1996), 83–84 and 258, with Table 10.1, based on Étienne and Rachet (1984), 333–334, 421–422.

21. Harl (1996), 250–269; Reece (1984), Fig. 1. For circulation of coins in military camps, see Kemmers (2006); Howgego (1992).

22. Finley (1985), 166–167.

23. The case has been restated most recently by von Reden (2010), 18–125, arguing that local economies of the Roman Empire were based on bronze tokens and that credit was an index of chronic scarcity of coins; cf. Harl (1996), 15–18. Credit increased the velocity of specie in circulation and furthered monetization; see Braudel (1979), 390–397, for analogous use of credit in early modern Europe.

24. Finley (1985), 167.

25. Kurke (1991); (1999); Seaford (2004).

26. Von Reden (2010), 89–92 argues that imperial fiscal expenditure and trade were local or regional, and thus of limited economic impact; so also Wolters (1999), 233–234. Cf. Hopkins (1980) with Kessler and Temin (2008), whose study of prices bears out Hopkins’ position.

27. Le Rider (2001), 187–196.

28. Price (1991), 29–34, 71–80; Boehringer (1972), 6–8, 32–64. For posthumous Lysimachi, see Mørkholm (1991), 35–36, 145–148; Stoljarik (1997).

29. Tac. Germ. 5, 46; finds of coins bear out his remark, as at Wheeler (1954), 54–60.

30. Harl (1996), 103–104.

31. MacDonald (1992), 17–20; Klose (1987), 103–114.

32. Kraft (1972), 13–21; engravers operated from a major city (called Werkstätte by Kraft), or traveled from city to city.

33. For circulation and production, see Tschoegl (2001); Gervais (1982). For an introduction to the series, see Semple (2006).

34. The coins are 39.5 mm diameter, 2.5 mm thick, 28.066 grs; .0833 fine for silver content of 23.389 grs, or 0.752 Troy ounce.

35. Stride (1956).

36. Harl (1996), 298 with pl. 32, nos. 262–263.

37. Kraay (1976), 230–231.

38. Crawford (1974), 43–51; cf. Harl (1996), 28–29.

39. Macr. 1.7.22; cf. Origo gentis Romanae 3.5.

40. For the issues of 213–212 BCE, see Crawford (1974), nos. 4/1–11; Buttrey (1965). For coins of 141 BCE, see Crawford (1974), nos. 225–228, with discussion by Buttrey (1957).

41. Harl (1996), 139–140. For value marks on coins of Side, see Kromann (1989), but her suggestion of pieces marked IA as denominations of 9 or 11 assaria is implausible; they are 10-assaria pieces.

42. Klose (1987), 110–114; cf. Harl (1996), 139–140.

43. Harl (1996), 145–147. In his Egyptian regnal year 6 (274–275 CE), Aurelian also reformed the billon tetradrachma of Alexandria that was revalued at parity with the new aurelianianus; see Metcalf (1998).

44. Specimen of Side (Gallienus; cf. SNG v Aulock 4841, 4848) so countermarked in K. W. Harl Collection.

45. OGIS 484 = ESAR IV 892–895 (T. R. S. Broughton); see discussion by Macro (1976).

46. ESAR IV 879–881, for bread prices at Ephesus (cited in obols) of the second century CE.

47. The edict of 38 CE from Cyzicus (IGRR IV 146) imposes maximum prices in the market there that might have been disrupted due to renovations; partial translation in Lewis (1974), 49 no. 18. See OGIS 515 (Mylasa) = ESAR IV 895–897 for regulations on exchange probably issued by Septimius Severus and Caracalla. For such regulations as precedents for the Edict of Maximum Prices, see Corcoran (2000), 213–215.

48. See Jones (1964), 438–48; MacMullen (1976), 96–128; cf. Potter (2014), 138–140, 268–270, 385–387; Corbier (2005).

49. See, notably, Mickwitz (1932), 80–178, for such a vision of inflation and collapse of imperial coinage in 235–284, one still widely accepted: note von Reden (2010), 54–55; cf. Depeyrot (1991).

50. Kent’s argument (1956) that Roman gold coins were privilege bullion rather than true coins influenced subsequent interpretations.

51. Finley (1985), 166.

52. Zos. 1.61.3 is our only source for the reform; cf. Harl (1996), 136–143. The coin’s diameter is 22 mm; weight 4.00 gr. (probably struck at 80 to the Roman pound).

53. The nummus circulated as the new denomination of 5 d.c., and the aurelianiani in circulation were perhaps revalued at 2 d.c.

54. Harl (1996), 155–157. The nummus is 29 mm in diameter; weight between 10.00 and 11.50 gr. (probably struck at 32 to the Roman pound). For the value of 5 d.c., see Harl (1983); cf. Hendy (1985), 452–462; contra an initial value of 10 d.c. argued by Erim, Reynolds, and Crawford (1971), 175–176. For inflation affecting soldiers, see Edictum de Pretiis Maximis, pref. 14; cf. 6.

55. See Rathbone (1996), 321–329; (1997); (2009); fundamental to his analysis is Duncan-Jones (1976). For a critique of his method and conclusions, note Bang (2008), 152–173. See Lendon (1990), 110–111, for fourfold inflation of wheat prices after 275; but he ignores two numismatic complications, the fiduciary nature of the Egyptian tetradrachma and the recoinage necessitated by the reform of the coinage in 274/275: see Harl (1996), 118–124.

56. See CPR V. 26. 604–605 (around 435 CE) for collection of two-thirds of the land taxes at Skar, in the Hermopolite nome of Egypt, in bronze fiduciary coins, even though the obligations were reckoned in solidi; see Harl (1996), 178–179.

57. RIC VIII pp. 46–47; the total number of officinae was reduced by 52% from 73 to 35.

58. C.J. 11.11.2; see Hendy (1985), 473. The law was probably issued in tandem with C. Theod. 11.21.1 (371 CE), which ended the striking of silver-clad coins (aes dichoneutum). See Harl (1996), 172.

59. Erim, Reynolds, and Crawford (1971), but the value of the nummus here should be restored as 25, not 20; see Harl (1983).

60. See Lauffer (1971); Giacchero (1974), with translation in ESAR V 305–420 (E. Graser). Rathbone (2009), 321, draws attention to the need for a complete new edition of the Edict accompanied by reevaluation of documentary papyri with price series, especially in the light of new inscriptions from Aezani; see Crawford and Reynolds (1979).

61. Naumann (1973), 28–35, and Fig. 13.

62. Bolin (1958), 302–303, identifying the 5 d.c. and 2 d.c. coins as the nummus and post-reform radiate, respectively.

63. Lactant. De mort. pers. 7.7.

64. The date of the edict’s withdrawal is uncertain: see Corcoran (2000), 232–233.

65. See Harl (1996), 163–167. For the prices recorded in Attic drachma from the dossier of Theophanes around 320 CE, see Matthews (2006), 138–179. Note further the collection of prices in Szaivert and Wolters (2005).

66. Cod. Theod. 9. 23. 1; Hendy (1985), 470–471.

67. Metcalf (1969); cf. Harl (1996), 193–195.

68. Standard studies: Timberlake (1993); Studenski and Krooss (1952).

69. For comparison, note Dowling (1972) on the United Kingdom’s needs when it adopted decimal coinage in 1971.

70. As seen from the tax registers of Karanis: Harl (1996), 234–238.

71. Hdt. 1.94.1–2.