26: “I Can Recognize a Beginning” (1962)25

Jeri Cross, Sandra Johnson, and Bruce Wilkie

The Workshop on American Indian Affairs served as an intellectual training ground for a generation of activists.26 Over six weeks, scholars, lawyers, political figures, and tribal leaders introduced students to social scientific theories regarding race, folk and urban societies, culture and personality, marginality, inner- and other-directedness, pan-Indianism, nationalism, colonialism, and the history of Indian-white relations. Cherokee anthropologist Robert K. Thomas (1925–91), one of the curriculum’s primary architects, wanted young people to liberate themselves from the “old bugaboo of race,” the “bullshit dilemma” of supposedly having to choose between “being Indian” or “being white,” and the system of colonial oppression that lay at the heart of the real “Indian problem.” Consider how the following excerpts from essays written during the 1962 workshop lend insight into the different kinds of “awakenings” students experienced—about themselves personally, about the possible futures of their communities, and about the structural causes of disempowerment. You will find additional information about the authors and the questions to which they responded in the notes.27

Jeri Cross, “A Thought”28

With all the wisdom of a sixteen-year old whose observations of life’s complexities though limited were very concrete, I asked my mother why didn’t she raise my younger sisters and brothers as whites. She smiled (I remember the smile—a sheepish one) and she said, “I tried that on you four older girls.” Her philosophy—to inject as much white or European thinking into her children and to discourage Indian ways in them—was not a surprising one considering the public school situation to which we were exposed and also the “lazy” Indians with whom (we were continually being reminded) we lived.

Since my mother is the most wonderful person in the world, I quite easily acquired her viewpoint. However, a mother’s medicine isn’t in any way as potent as powwows, forty-nines and stomp dances. And smooth-faced, non-hairy chested Indian boys effortlessly and unanimously won the case for Indians for us girls.

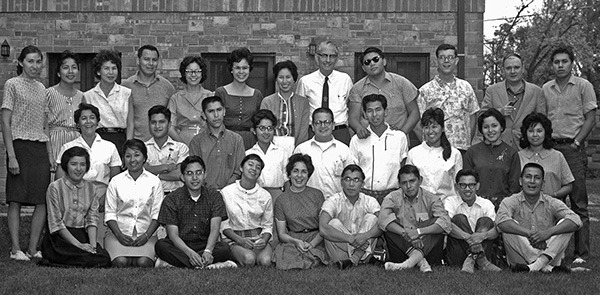

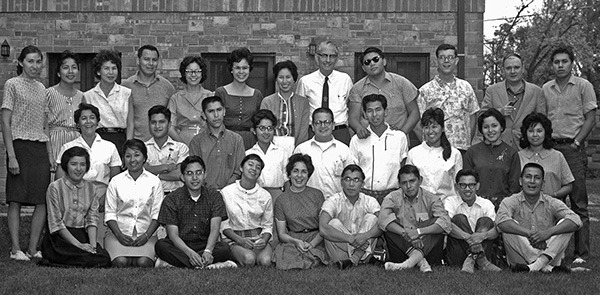

Robert K. Thomas considered the 1962 Workshop students to be some of the best he had ever taught. Among them were Bruce Wilkie (back row, fourth from left); Jeri Cross (back row, fifth from left); and Sandra Johnson (front row, fifth from left). Also in this photo are Fran Poafpybitty (to the right of Cross, noted in Document 29), Thomas (back row, second from right); and Clyde Warrior (back row, far right, Document 27). D’Arcy McNickle Papers, Ayer Modern MS, The Newbery Library, Chicago.

Two conflicting social opinions existing in the mind of one person do not encourage a restful night’s sleep (or nights’ sleep). Trying to uphold two separate and I mean separate—social circles is a job for Superman; he alone can ably cope with two identities and remain a sane person. To me assimilation was best for all concerned (especially us) in the long run. It became my duty not only to Americanize myself but to drag (?!!!) others with me. Always a conscientious, duty-bound conformist, I complied, and then I literally played Indian against white in a cat and mouse game which neither one could possibly win. What an encouraging catharsis to know it’s possible to be myself. To suggest a drastic turn over in my thinking is far from true, but I can recognize a beginning.

Sandra Johnson, “What do you hope your community will be like 20 years from now and why?”29

Twenty years from now I would like our community to be self-supporting and responsible. I would like to see a few businesses controlled by Indian people and those white people who do own businesses—I would like to see a corporate tax placed on. An effective, efficient tribal government would be wonderful to visualize. As for the physical features—I would like to see a sewage system, paved streets, and an adequate housing program—a clean up the town campaign would be needed. Law and order are the big questions. I would like to see local effective law and order or an outside appointed policeman. I do not think it desirable to grow up in a community where everything is allowed—where drinking is the rule and not the exception. The local parents also express this view, although they never bring it up at the meetings. I would like to see this, because I consider these goals all desirable. Furthermore, I believe most local people want this and although I have made no scientific survey—the general consensus seems to be “It would be nice, but it’ll never happen”—a real fatalistic non-trying point of view—although it’s understandable.

Being realistic, I would say that it will all start with a few individuals—to get the ball rolling. If Bruce [Wilkie] gets the chairman’s position—that will be a big start. From there the most helpful information has been the [Area Redevelopment Administration]. To get the council’s approval will be the difficult part. Every change will be slow and will be by individuals. A college education will be necessary for some of our tribe and a growing ambition—I have no concrete answers other than to go into the community, find out if their “wants” are like mine, and try to accomplish it. Much study on my part will be necessary and thanks to the workshop—my interest has been aroused.

Bruce Wilkie, “Describe the consequences for the world and social relations of a folk people under a colonial administration”30

Under a colonial administration, like that of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, responsibility of self-government is withheld from the people. All matters concerning the Indian community must meet the approval of the Indian Bureau. Although an Indian council may be elected by popular vote every one of its actions must meet the approval of the Indian Bureau. In essence decision-making is taken out of the hands of the people concerning their community as a whole.

The consequences of this colonial structure on the Indian community is general apathy concerning Indian affairs. With responsibility and decision-making taken away from them, the Indian people have little or no faith in the system of government imposed upon them. The Indian council is, in reality, a figurehead body providing a buffer between the Indian people of the community and the colonial administration (the Indian Bureau). Widespread suspicion prevails among the Indian people concerning the Indian Bureau and Indian council. Most programs designed to aid the Indians, initiated by the Indian Bureau, meet with little success because the Indian people for the most part, want to do things their way. Such a program fails because the Indians have very little, if any, enthusiasm for any programs not originating within their own group. . . .

The Indian people, concerning matters of government, foot it for themselves. No form of governing agency is going to tell the Indian to do anything against his wishes—because, in effect, he did not put the governing agency in its position. . . . The worldview becomes very narrow emphasizing skepticism on most institutions which are not “Indian.” Social relations are strained not only between whites and Indians but also among Indians themselves. Whites feel the Indians incompetent because they appear not able to handle their own affairs. Indians are suspicious of whites and relations are strained among Indians because they are denied the right to handle their own affairs. Group dignity appears lacking because the Indians are not allowed the prerequisite to group dignity—self-government. . . .

In twenty years my hope for my community is one of complete self-government, group dignity, and individual participation in the welfare of the community. In order to achieve this end, a major change in governing structure must take place. The Indian Bureau will have to return the responsibility and decision-making of government to the people. Federal obligations must be continued in the form of assistance, protection—but the assistance must be administered by the Indian people themselves. The present form of tribal government must be revised to a form which would return power to the people. The Indian people will have to make their own mistakes and learn from them. . . .