31: “I Want to Talk to You a Little Bit about Racism” (1968)46

Tillie Walker

Tillie Walker, a Mandan-Hidatsa from the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota, directed the United Scholarship Service, an organization that promoted attendance in elite preparatory schools and provided scholarships to college students. In that capacity, she networked with many organizations involved in Native politics and built particularly strong ties with the National Indian Youth Council. In early 1968, Walker became immersed in organizing the Indian contingent of the Poor People’s Campaign, a massive interracial coalition of the poor that intended to march on Washington in the spring and stay there until Congress took action on poverty and hunger. The devastating impact the construction of the Garrison Dam had on Fort Berthold served as one of the impetuses for her activism, and residents in that community turned out in large numbers for the campaign. Consider what this document, drawn from a presentation she made during a meeting with Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, reveals about the interplay between the politics of race and class during the 1960s.47

My name is Tillie Walker and I am from the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota and I live in Colorado. I want to talk to you a little bit about racism. I was involved in the Poor People’s Campaign since March 14, at the invitation of Dr. Martin Luther King. There were about 15 Indians invited to that meeting, so that all races across the country could meet together, and see what they felt about something called the Poor People’s Campaign.

I called around when I got the invitation to see who else would come. And I want to tell you something about the response that I had, because it does involve you, and it does involve the people you have on the reservations and in the cities. I went to Fort Berthold reservation right after March 14, my brother is the Community Action Director there, and I asked him to see whether the Tribal Council would be interested. I have many relatives on the Tribal Council and they said, yes, please come up.

On the way up, I stopped at the United Tribes meeting in Bismarck, North Dakota and when I told them about the Poor People’s Campaign, one of their responses was, one member said, “You will never get a Tribal leader to come because they all have their hands in the pork barrel. You’ll never get any tribal leader to be a part of this.” But this didn’t stop me. I went to Fort Berthold and talked to the Tribal Council and they voted unanimously to come. Before I talked to them, Mr. Secretary, one of my uncles told me the Superintendent of the Reservation told him there was too much to lose. “Indians don’t act like that. Indians don’t do things like that.”

After this, I went to Standing Rock Reservation at the invitation of a former classmate of mine, and I found a lot of stone faces there. The response was good though, because they said, “we should be a part of that Poor People’s Campaign.” And my relatives there told me they had heard you from the Aberdeen office saying “Indians don’t do things like that.” And you know what they mean, Mr. Secretary? They mean that Indians don’t work with Negroes in this country. That is racism. And I am angry. [Applause]

When I got back to Denver, I had a call from the head of the Relocation Office in Denver and he said to me “Who is this rabble-rouser up in North Dakota who wants to get involved with something about a Poor People’s Campaign? Is his name ‘Mad Dog?’”48

I said I was involved in the Poor People’s Campaign because Indian people are poor and the poor know no color.

Before your men out in the field, Mr. Secretary, tell us things like this, and before we will talk to you anymore, you ask the Standard Oil Company to give up their oil taxation allowance, then we will talk to you about how much we have the lose. Before you have your men out there talk to us about too much to lose, have them go out there and live on the 320 acres I own and live off of that, with fifty cents an acre or a dollar an acre, for a year. You are welcome to come, too. [Applause]

Before they tell us that we have too much to lose, Mr. Secretary, in being a part of the Poor People’s Campaign, let them tell us how much they earn, sitting on their reservations and telling our people that they should not be a part of this, because there are Negroes in it. I am tired of this kind of racism. And I won’t stop recruiting. [Applause]

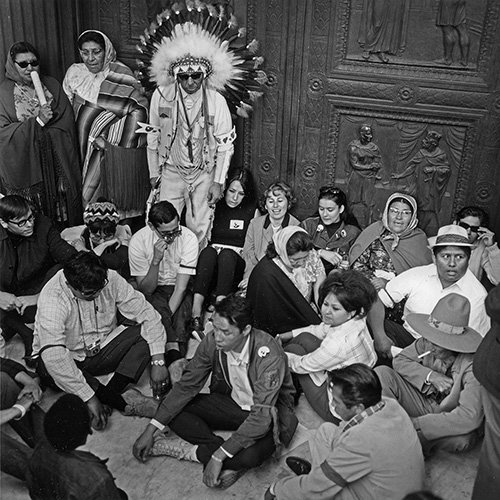

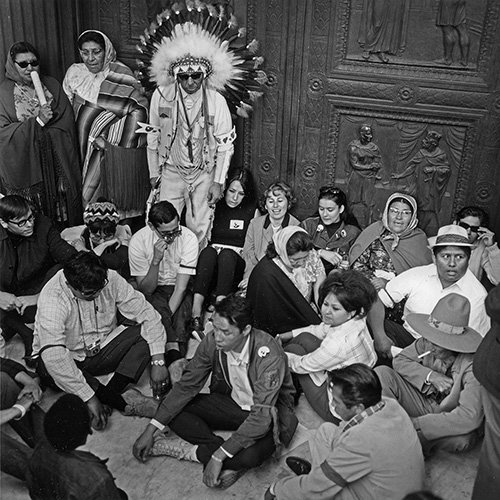

Native activists, including Tillie Walker (back row, seated fourth from right, Document 31), conduct a sit-in before the doors of the Supreme Court to protest the Puyallup decision during the Poor People’s Campaign. Karl Kernberger Pictorial Collection, Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico, photograph 2000-008-0116.

We are tired of all the programs coming out of Washington. We are tired of all the conditions that are being set up. We are tired of our Tribal leaders being owned, and we are going to be back in Washington, even if it is just a handful who are here, and we are going to tell about what is going on. And don’t tell me that I am a non-reservation Indian and I can’t speak. Because my family lived in the Missouri Valley long before Columbus ever set his feet on these shores. [Applause & standing ovation]