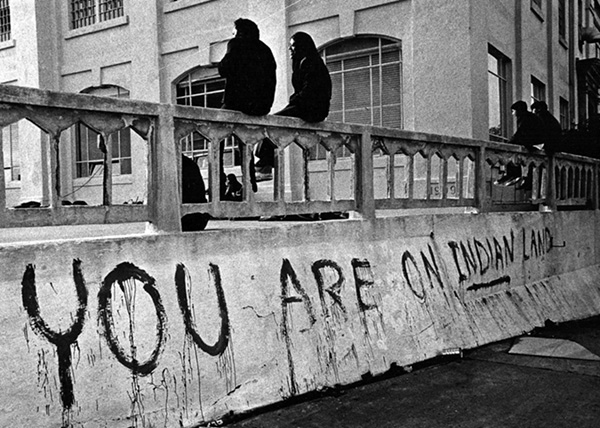

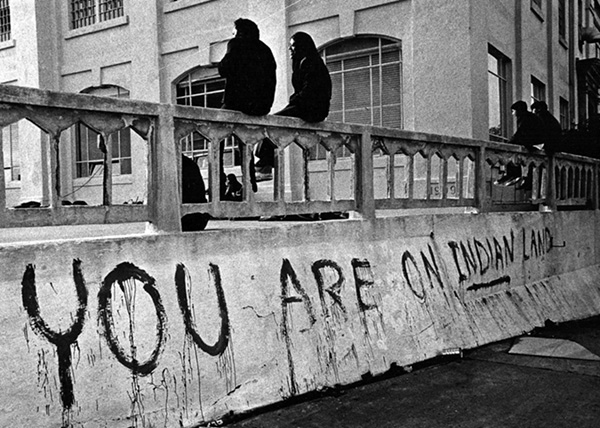

The occupation of Alcatraz in November 1969 instantly became a symbol of indigenous survivance. It continues to figure significantly in resistance and rights movements. Photograph by Bill Wingell, used with permission.

To deflect the “freedom program” of terminationists and avoid conflation with civil rights from the 1950s through the early 1970s, Native activists developed a vocabulary to discuss Indian concerns that the majority society could understand. Essentially, this amounted to connecting ideas and issues in Native America to matters of pressing national and international concern to prevent them from being dismissed as unimportant or obscure. In so doing, they endeavored to move American Indian politics from the margins to the center of the public sphere. Vine Deloria Jr. referred to this art of drawing parallels, connections, and associations as talking “the language of the larger world.”1 Though a master of the craft, he was certainly not its lone practitioner. In fact, as the previous chapters demonstrate, Deloria inherited an American Indian political tradition: Lili‘uokalani spoke the language of imperialism; the All-Pueblo Council spoke the language of religious freedom; D’Arcy McNickle spoke the language of international development; and so it continued.

If the rhetorical strategy represented continuity, the ways in which it manifested itself shifted with changing contexts and circumstances. The linking of Native rights to decolonization, for instance, gained salience and sophistication from the late 1960s to the mid-1990s. After occupying the abandoned federal prison on Alcatraz Island in November 1969, for instance, demonstrators laid claim to “the Rock” on behalf of the “Indians of All Tribes.” Elaborations on the intellectual and philosophical connections between Native America and the indigenous world, as well as the creation of mechanisms for shared political action, followed. During the 1970s, the American Indian Movement (AIM), Women of All Red Nations (WARN), and National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), for instance, publicized crises in Latin America and built alliances with indigenous organizations.2 Meanwhile, the Iroquois Confederacy and newly formed International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) spearheaded efforts to gain formal representation for tribal governments in the United Nations (UN). Like the League of Nations before it, the UN often did a better job of talking about decolonization and universal human rights than actually promoting them. Nonetheless, Native activists insisted on being a part of the conversation.3

Like Deskaheh before them, 1970s-era activists could not compel the United Nations to recognize tribal governments as equal members of the family of nations. The IITC did, however, set a precedent in 1977 by securing consultative status as a nongovernmental organization in the UN Economic and Social Council. By the 1980s, aggressive lobbying on the part of indigenous groups led to the establishment of the Working Group on Indigenous Populations within the UN’s Subcommittee on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights. The working group’s efforts then culminated in the Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 1993, an important statement that faced a difficult path to formal adoption—one that would take another decade and a half to travel.4

Activists simultaneously carried forward the struggle for sovereignty at home. The American Indian Movement emerged as the most visible force, spearheading the Trail of Broken Treaties and Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) occupation in November 1972 and the standoff against the federal government and Pine Ridge tribal council at Wounded Knee in the early months of 1973. AIM originated in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area in July 1968 and initially focused on discrimination and police violence in urban communities. Its scope soon broadened to include all Native—and ultimately all indigenous—peoples. Their Twenty Points, drafted in large measure by NIYC member and fishing rights veteran Hank Adams (Assiniboine) for the Trail of Broken Treaties, provided a clear articulation of the Native rights agenda, one founded on tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, and the restoration of nation-to-nation relationships.5

By the mid-1970s, the federal government abandoned termination in favor of an approach founded on the principle of self-determination. A flurry of legislation followed, including the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975), the Indian Child Welfare Act (1978), the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978), the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (1988), the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990), and the Indian Self-Governance Act (1994). In addition, the Taos Pueblos secured the return of their sacred Blue Lake in 1970; the following year, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act recognized title to 40 million acres of land, provided monetary compensation, and established twelve regional corporations to promote economic development; and in 1980, Penobscots and Passamaquodies wrested an $81.5 million settlement from Congress for the illegal taking of what amounted to two-thirds of the state of Maine.6

The occupation of Alcatraz in November 1969 instantly became a symbol of indigenous survivance. It continues to figure significantly in resistance and rights movements. Photograph by Bill Wingell, used with permission.

These victories were, in reality, compromises—and not always satisfactory ones. What is more, throughout the period tribal nations had to deal with pendulum swings in Congress and the courts. It seemed as though a step forward in one area brought a step back in another. Congress produced its share of detrimental legislation during this period, and the courts delivered several stunning defeats in areas where victory seemed to have been secured. Among the most debilitating proved to be the Oliphant decision, which denied tribal courts criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians.7

The documents in this chapter chart a continuing tradition of asserting sovereignty through a vast array of strategies and techniques in contexts that ranged from the grassroots to the global. Whether demanding a place among the family of nations in Geneva, defending the use of a sacrament the majority society dismissed as a drug in Washington, D.C., or reminding federal legislators that tribal sovereignty predated that of the United States, American Indians offered a vision of what it meant to be citizens of enduring nations. But declaring continuing independence proved to be the easy part. Acting on it was another matter altogether. As tribal leaders and Native activists engaged issues of economic development, religious freedom, federal recognition, and self-government, they found that the ground they were gaining during the so-called era of self-determination remained uneven and contested.