5 HACKERSPACES

MEMORY AND FORGETTING THROUGH GENERATIONS OF SHARED MACHINE SHOPS

In the previous chapters, we have discussed how informational capitalism responds to critique by implementing the demands of critics while simultaneously subverting the meaning of those demands. This is what we call recuperation. Even so, the process of recuperation is open to contestation and contingency. In the case of the Ronja project, analyzed in chapter 3, recuperation was successfully resisted, but at the price of the development process stalling when the community imploded under the weight of factional conflicts. In the case of RepRap, analyzed in chapter 4, the community’s failure to resist recuperation is demonstrated in the emergence of a consumer market in desktop 3D printers. However, the organizational idea at the heart of the RepRap project, to distribute manufacturing capacity to society at large, proved more difficult to assimilate under a logic of commodity production. The decisive factor was the organizational difficulty of establishing managerial authority (also known as quality control) over a distributed production network. Hence, only the product innovation was successfully recuperated, while the potentially more disruptive idea of the RepRap project, to introduce a life-like logic of exponential growth and evolutionary change into the manufacturing process, proved unbending to the requirements of capital. This far into the argument, we need to substantiate the claim that recuperation processes form the overarching setting for any particular hacker project with its associated line of product developments. Recuperation acts concurrently on the legal, cultural, and technical landscapes that frame individual development projects, aligning those framing conditions with the requirements of state and industry.

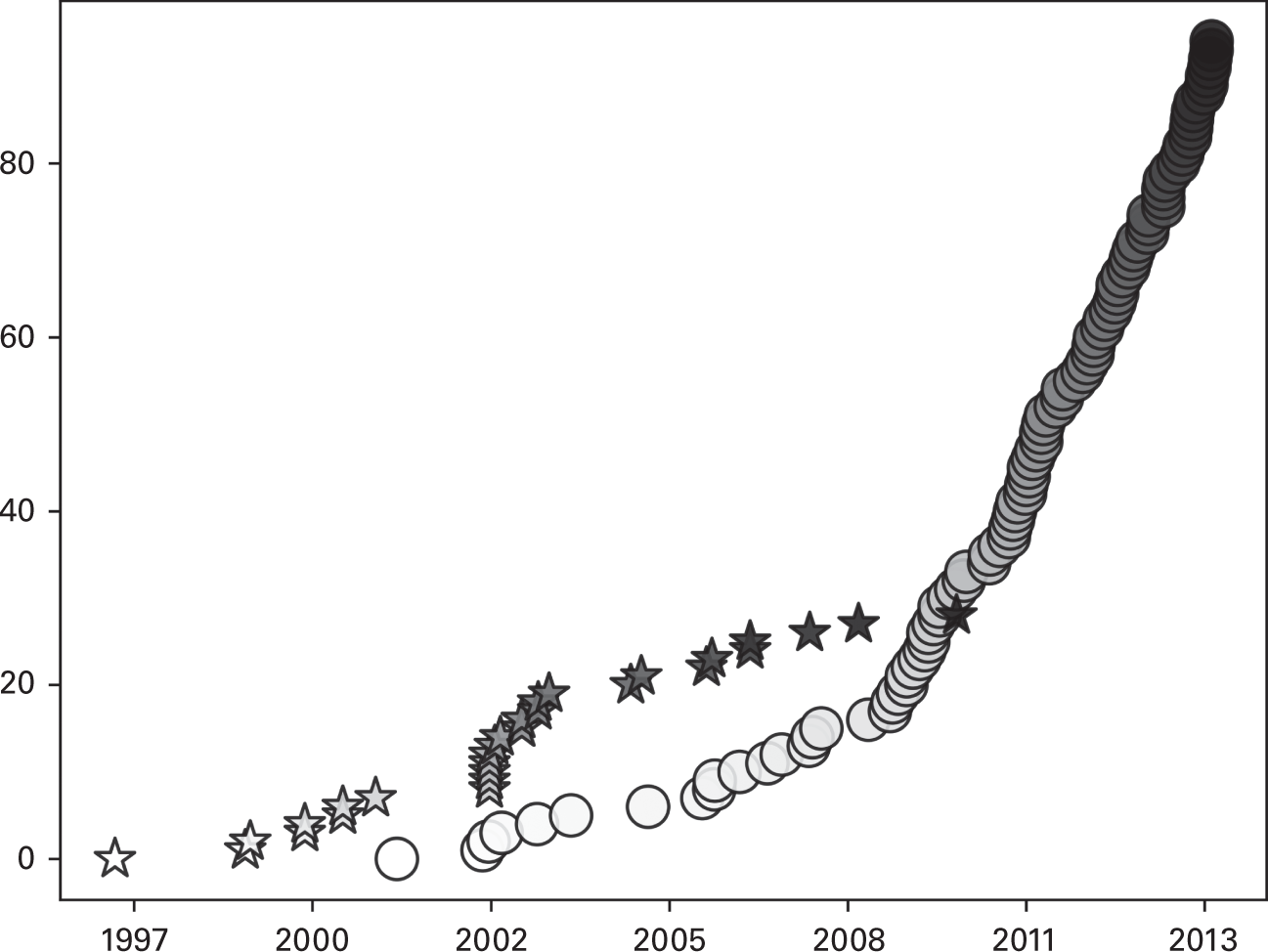

Hacklab vs. hackerspace domain name registrations over time (work of the authors). Stars mark new hacklab websites and circles mark new hackerspaces websites.

This is precisely what we set out to demonstrate in this chapter, through a comparative, ethnographic study of the historical succession of different genres of “shared machine shops.” Shared machine shops is not a practitioners’ term. It was introduced by one of the authors of this book in a different context (Troxler and Maxigas 2014). Since then, it has gained some traction in the academic literature (Bosqué 2015; Dickel and Schrape 2017; Foster and Boeva 2018; Wenten 2019; etc.). Under this umbrella term, we gather a range of distinct but related phenomena that the practitioners variously refer to as makerspaces (Davies 2017; Lindtner 2015), FabLabs (Troxler 2015; Kohtala and Bosqué 2014; Gershenfeld 2005), Tech Shops (Hurst 2014; Schneider 1998), Men’s Sheds (Wilson and Cordier 2013), incubators (Lindtner, Hertz, and Dourish 2014), hacklabs, hackerspaces, or accelerators (Cavalcanti 2014; Maxigas 2015). We will focus on the latter three subcategories of shared machine shops. They qualify for the denomination insofar as all three of them are physical locations where hackers, in addition to a more variegated assortment of practitioners, gather to socialize and collaborate on technology projects. Crucially, participants in hacklabs, hackerspaces, and accelerators all draw on hacker culture in order to distinguish themselves from other kinds of entities and subcultures. Furthermore, as will be clear from the discussion below, they have a historical lineage in common.

We home in on these three genres of shared machine shops due to their suitability for clarifying some analytical points about recuperation. Hacklabs showcase the most politicized space, as well as being the first instantiation of a shared machine shop. The other genres were spawned from this point of origin. Next in turn are hackerspaces. The activist credo of hacklabs has here been supplanted by an almost exclusive focus on tinkering with technology, concurrent with the promotion of the ethos of sharing and repairing. Jumping over a couple of intermediary steps, we close the discussion with a recent manifestation of shared machine shops, called “accelerators.” These are imbued with a rhetoric of job creation, urban and regional development, entrepreneurial exploits, and high-tech innovation. The three genres represent successive historical steps in a progressive logic of recuperation.

In the analytical scheme introduced in the theory chapter, the movement of shared machine shops is located within the second time horizon, situated in between the life cycle of an individual hacker project (first time horizon) and the epochal transitions in capitalism as an evolving whole (third time horizon). The intermediate level of shared machine shops is due to the fact that they provide a material infrastructure and cultural context within which individual hacker projects may run their course. It bears stressing that shared machine shops are key sites for the reproduction of hacker culture, both in the cities where they are located and at the aggregate level. Shared machine shops, alongside annual conferences and outdoor camps, are the physical places in which members regularly gather and confirm their own and others’ belonging to the same movement. Through such ritual gatherings, a compact social formation emerges that fills the otherwise hollow and abstract notion of “community” (Coleman 2010). In the process, common meanings are established and attention is drawn to matters of concern, potentially triggering collective action. What kind of identity a space adopts is therefore decisive for how much room for maneuver will exist for critical engineering practices—or, alternatively, how expediently such practices will be turned into technological and organizational innovations for capital.

By adopting a longer historical perspective on shared machine shops, our investigation extends across generational shifts within hacker culture. Thus, we want to stress the importance of shared historical memory. At stake is the transmission of the lessons learned from past events and engagements. What aspects of the past are successfully passed on from one generation to the next, and what aspects are omitted, is subject to incessant internal contestations and pressure from external actors. Later genres of shared machine shops feed off the imaginaries, legitimacy, and technical achievements of their forerunners. Concurrently, the different genres have come to enact very different political-economic agendas, something that we will demonstrate in relation to urban regeneration plans. In this, we find a telltale sign of recuperation.

Traces of an ongoing recuperation process can also be detected at an aesthetic level, such as, for instance, in the prevalence of graffiti on the walls of a physical space. This connects to the remark we made in the introduction with a reference to Immanuel Kant’s philosophy. It takes an aesthetical judgment to spot recuperation attempts. To substantiate this claim, we will conclude each section with a description of the patterns of indoor lighting that are typical in different genres of shared machine shops. Here we take a cue from satellite images of the night-time earth. In popular culture, the uneven distribution of light emissions displayed on those photos is taken to represent centers of economic activity versus areas of nonactivity. In the following pages, we venture to apply the same reasoning to shared machine shops. The intensity and rhythm of the light emitted from a physical space indicates the extent to which the space in question has been assimilated into the regular office hours of the surrounding society.

THE PREHISTORY OF SHARED MACHINE SHOPS

The proposal that we made at the outset of this book, with reference to William Morris’s allegorical tale of a peasant uprising, namely, that hackers are caught up in a whirlwind of social forces that can be meaningfully linked to a longer history of industrial conflicts, finds empirical support in the precursors to shared machine shops. The onset of deindustrialization in Western countries during the 1970s created the material conditions for a wave of social mobilization around the idea of a democratization of manufacturing capacities. A palpable, material trace thereof are the machine tools that many hackerspaces have inherited from defunct manufacturing firms in their vicinity. In many cases, the physical space itself is housed in the remnants of a former manufacturing building. More to the point, however, is that the very notion that the means of production can be reclaimed by setting up a shared machine shop “outside of the factory gates” is an outcome of defeats in industrial conflicts of the past.

Numerous authors before us have connected the movement of shared machine shops to the Lucas Plan in England and the subsequent promotion of technology networks for socially useful production by the Greater London Council (Smith 2014; Smith et al. 2017). Similar developments took place simultaneously in Scandinavian countries under the names Collective Resource Approach and participatory design (Ehn, Nilsson, and Topgaard 2014). Drawing support from trade unions, socialist parties, and universities, these interventions into the design process sought to strengthen organized labor in anticipation of the automation of industry. These initiatives have been documented and analyzed elsewhere, so we will give only a brief account of them here. The discussion serves to demonstrate the analytical benefits of studying hackers within the second and third time horizons—that is to say, to diagnose the trends of developments within a larger movement of hacker projects and, furthermore, to relate this trajectory to capitalism as an evolving whole. An unexpected outcome of deindustrialization and automation was that it set the scene for hacker culture to flourish.

Our interpretative framework resonates with Harry Cleaver’s concept of “cycles of struggle” (2017, 58), as well as its application in the context of information capitalism by Nick Dyer-Witheford (2015). The concept describes how forms of social contestation coevolve in tandem with the ever-shifting regime of capital accumulation. Technical innovations are interpreted as capital’s response to working-class resistance. A major restructuring of industry during the 1970s, coupled with automation, outsourcing, and financialization, allowed capital to dissolve the strongholds that the Fordist mass worker had mounted inside the production apparatus. The technical and organizational composition of the working class was thus also dissolved, along with its former identity constructions. A token of this is the difficulty of recognizing the present-day experiences of the working class as belonging within that old Fordist register.

On the basis of this conceptual argument, we advance the proposition that the rise of shared machine shops is not merely an unexpected, secondary outcome of the defeat of the Fordist mass worker. It concurrently inaugurates a new cycle of struggle, corresponding to the new cycle of capital accumulation. The struggle of hackers showcases how the extraction of value, as well as contestations against this extraction process, takes place outside of the contractual employment relation and the legally recognized “abode of production.”

In 1976, during a period of crisis for the whole of the British manufacturing industry, the military contractor Lucas Aerospace faced the prospect of insolvency. Workers took the initiative and drafted an alternative business plan to save their jobs while steering the arms manufacturing capacities of the firm toward “socially useful production.” For posterity, this initiative has become known as the Lucas Plan. The proposal included market research and blueprints for more than a hundred socially useful products. Coupled with the alternative design items was a reconceptualization of the labor process to involve the workers in strategic decision making. Representatives of the Lucas Aerospace Shop Stewards’ Combine Committee toured the country with one of their prototypes, a bus-train hybrid vehicle, to promote the idea to the public. Despite these efforts, the Lucas Plan stalled due to fierce resistance from management, the government, and the upper ranks of the trade unions. After its demise, social movements drew inspiration from the initiative and began to rally around the idea of involving a broader range of actors in the decision-making process over technology development. In a retrospective analysis of the Lucas Plan, Adrian Smith concludes that it “challenged fundamental assumptions about how design and innovation should operate” (2014, 2).

Next, the demand for socially useful production was championed by a motley coalition of left-wing Labour politicians, neighborhood community groups, peace activists, and the nascent environmental movement. The authoritative account of these movements was given in the book Architect or Bee? The Human/Technology Relationship by Mike Cooley, the key promoter behind the Greater London Enterprise Board (1987). At the moment when Margaret Thatcher was ascending to power, the Greater London Council asserted itself as a holdout of labor power. The economic policies of the national government were resisted at the municipal level. It was within this highly conflictual political climate that the network of community machine workshops was inaugurated on London’s outskirts. The invitation to local residents to become involved in the creation of alternative technology was framed as a challenge both to managerial authority on the shop floor and neoliberal government policies. The stress placed on “alternative” pathways in technological development was taking aim at the rhetoric of technological and economic determinism, succinctly put in Margaret Tatcher’s slogan: “there is no alternative,” which underpinned the ideological scaffolding of neoliberalism in those early days (Greater London Enterprise Board 1984, 34).

Examples of items produced in the neighborhood workshops include “small-scale wind turbines, energy conservation services, disability devices, products made from recycled materials, toys for children, community computer networks, and a women’s IT co-operative” (Smith 2014, 1). These were documented and registered in an open-source database as the potential basis for co-operatives, founded with support from the Greater London Enterprise Board, while the movement spread to other cities. The workshops became a hub of activity linking a variety of actors who were invested in the idea of socially useful production. The eventual decline and demise of the movement coincided with the consolidation of Thatcherism, epitomized by the suppression of the miners’ strike in 1985. The Greater London Council, led by Ken Livingstone who championed the movement, was abolished the following year.

This all suggests that the birth of the idea of “socially useful production” and neighborhood-controlled machine workshops were closely linked to the fate of the British working class at the onset of deindustrialization. Proposals of the same kind surfaced in other countries where the working class faced similarly bleak prospects. Academics working in liaison with trade unions launched the participatory design movement in Scandinavia and the science shops movement in the Netherlands. These initiatives were prompted by the anticipated social consequences of a nascent technology that, back then, was mostly associated with factory automation, namely computerization. The participatory design movement aspired to involve workers in the decision-making process over information technology and the design of human–computer interactions. A case in point was the digitization of typesetting (e.g., “the transition from lead composing to computer-based text processing and phototypesetting”), where the participatory design approach figured as an “intervention into managerial and technical plans for manning, education, investments, etc.,” rooted in “Marxist labor process theories and the practical experience of the investigation groups” in which workers participated (Ehn 1988, 12). Retroactive accounts, such as that by Kraft and Bansler (1994), suggest that, in spite of the good intentions of the academic researchers, these interventions achieved limited success.

The underlying concepts, along with the associated political interventions, underwent the familiar dialectic of critique and recuperation. Here, we can only briefly trace this trajectory. Some inflections in the terminology are, however, suggestive. “Cooperative design” turned into “participative design,” later to be reinvented as “co-design.” The centrality of workers in the design methodology was gradually pushed aside and replaced with a more varied assortment of “users” and “stakeholders.” Whereas the original proposals of participative design had been anchored in a society-wide analysis of the class antagonism between workers and management, later reformulations sought to foster consensual work relations by identifying cost-efficient solutions to remove direct sources of employee discontent.

The science shops movement followed a similar trajectory. In the early days, the case for democratizing science was made as an intervention on the side of labor in the class conflict. Scientific knowledge production was understood to belong to the arsenal of managers, while trade unions had far fewer resources to pool into methodological research about hazardous working conditions, the benchmarking of productivity, strategic foresight, and so on. Science shops sought to remedy this imbalance by elevating trade unions to clients of research output. The topics of PhD theses, dissertations, and research projects would be formulated and implemented in collaboration with trade unions and factory workers.

The first science shop was established in 1977 at the University of Amsterdam on the initiative of the Department of Science Dynamics. Another notable project included the consultation on an electronic payment system involving the national post office, clerical workers, and service companies (Leydesdorff and Van Den Besselaar 1987). A retrospective evaluation by former participants concludes that “the disappointments over the role of experiments” were due to the declining power of the unions, which could not muster organizational or research power to match that of the parties on the other side of the negotiating table (Leydesdorff and Van Den Besselaar 1987, 156). The critique of scientific knowledge production in the service of capital was duly recuperated at the moment when broadened participation in decision-making processes became a way of justifying existing work relations. A case in point is the dialogue panels on science and consensus conferences, staged by the European Commission to bestow legitimacy on its business-friendly, laissez-faire innovation policies (Horst and Irwin, 2010; Kelty 2019, 156–157).

The cases mentioned above, the Lucas Plan, the municipal network of neighborhood community workshops, the participatory design initiative, and the science shops movement are precursors to the subsequent wave of shared machine shops. Although the older examples are, biographically speaking, disconnected from hacker culture, they converge thematically in the vision of democratizing scientific knowledge production and technology development. This vision was first articulated in the context of industrial conflicts during a period of crisis and structural reform. The all-important difference between these two periods is that the initiatives of the first period sought to challenge capital’s prerogative over science and technology from within established institutional arrangements. Although the experiments in bottom-up decision making often clashed with union and party leadership, whose resistance proved decisive in many instances, the whole undertaking was nevertheless framed by trade unionism and electoral politics. The decline of both of these institutions in the following years concurrently spelled an end to the experimentation taking place at their fringes. In Cleaver’s assessment, for cycles of struggle to be effective, they must eventually break loose from and prevail independently of the circuits of capital: “The primary implication that I draw from what I have sketched is how revolutionary struggle must involve not only the rupture of the circuits of capital but escape from them through both their destruction and the creation of alternative social relationships. Doing so certainly requires recognizing the patterns of those circuits as well as their content—the endless imposition of work and the subordination of life to work. But such recognition is only meaningful if it informs rupture and creation” (Cleaver 2016, 23).

When hackers challenge capital’s prerogative over science and technology, the challenger is located outside of contractual wage relations and occupational identities. The outsider position of the hacker vis-à-vis formal institutions modifies the terms of conflict. Inside the confines of the employment contract, managers and employees are locked into antagonistic opposition over what expenditure of time and effort is deemed equivalent to a fixed amount of remuneration (i.e., wage). This is not an issue for hackers, who dispense their creativity freely on a nonremunerative basis. Instead, strife in the computer underground circles around keeping the results of their collective endeavor within the information commons. The information commons has to be protected because it allows hackers to hack, serving as a resource pool of ideas, standards, code, data and tools. In other words, it is part and parcel of the material conditions that allow them to reproduce the social relations that make them hackers. This interpretation of hacker culture resonates with the stress put on worker autonomy by Cleaver and others within the same branch of Marxism. Hacker communities have established themselves as autonomous sites of value production. The reverse side of the same trend is capital’s reorientation toward capturing value across a heterogeneous field of activities and interactions. Hence, hackers confront the threat of seeing their collective existence as hackers subsumed under capital and optimized to the needs of an open innovation model.

As will transpire from the discussion below, the outsider position of hackers in relation to both capital (contractual employment) and the political institutions of the Fordist mass worker (trade unions, socialist parties) gives no guarantee against them becoming incorporated into institutional arrangements of a different sort. With each successive genre of shared machine shops, both the concept and the practices have become increasingly aligned with the requirements of state and industry. Further down in the text, we argue that this trend can be detected from the different roles that different genres of shared machine shops have played in urban regeneration plans and real estate development. When the history of shared machine shops is recounted within the second time horizon, it is a story about decline. In the frame of the third time horizon, however, the story is about one cycle of struggle being supplanted by another, corresponding to a period of restructuring of capitalist processes of accumulation.

HACKLABS

With the term “hacklabs,” we are referring to the first generation of shared machine shops that drew inspiration from and linked up with hacker culture. Many hacklabs started out as media technology hubs inside squatted social centers. Geographically, they were concentrated in Italy and Spain, where the squatting scene was particularly strong. Hacklabs provided technical support for demonstrations and day-to-day activities at the social centers. A leading theme of the setting was the idea of “territory of autonomia” (Wright 2002). In the native language of these movements, the link to workplace struggles was explicit, although this is not explicit in the English translation. What are referred to as “occupied social centers” in English go by the name of Centro Sociale Okupado y Autogestinado in Spanish or Centro Sociale Occupato Autogestito in Italian. The last word stands for “self-management.”

A milestone in the organization of hacklabs as a social movement in its own right was the 1999 hackmeeting at the Centro Sociale Occupato Autogestito in Milan, known as Deposito Bulk (ana 2004; Anarchopedia contributors 2006; “storia” 2010). During a three-day session, the social center brought together politicized hackers, media activists, and squatters, who put on a program that mixed a festive spirit with hands-on experimentation, as well as workshops, talks, and debates. The gathering was underwritten by the pirate-anarchic ethos of Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zones (1991). The notion strongly resonated with practices and imaginaries of independent media activism located in occupied social centers. The “T.A.Z.” concept, as it was often stylized, celebrated the precarious conditions of these settings. Freedom nested for a brief moment in the inevitable cracks and crannies within large, oppressive, and overly complex systems of domination. Adding to this ideological inventory were celebrations of nomadic life and rhizomatic networks (i.e., the insignias of Deleuzian philosophy).

Participants at the hackmeeting in Milan, dirty and tired but thrilled to be part of a Temporary Autonomous Zone, decided to render the experience permanent by establishing hacklabs in occupied social centers in their home towns. Isolated experiments that had already existed, such as FreakNet in Catania, Sicily, provided inspiration and stability to the emerging network of hacklabs. As Bazzichelli observed some years later, “cyberpunk in Italy has taken on the connotations of a political movement” (2009, 68). Annual hackmeetings and local hacklabs constituted the spatial-temporal dimensions of political cyberpunk (Bazichelli 2009, 68–75).1 The network of hacklabs gradually spread from Italy to other countries with a strong tradition of squatting and autonomous politics, although its stronghold remained in southern Europe, where Italian and Iberian hackmeetings continue to this day.

Hacklabs ran on recycled hardware, bootlegged internet access, and free software. In the spirit of the social centers, which catered to their neighborhood communities with cultural happenings, vegan kitchens, daycare services, and so on, the hacklabs provided free public access to computers and the internet. In addition to providing computer access for the public, hacklabs typically organized workshops, ranging from teaching basic computer use and staging GNU/Linux installation parties to educating social movement activists in computer security and cryptography (Yuill 2008, para. 7). In return, the squatters offered the basic material conditions for the hacklab to exist in the first place, a residence, often located in a prime metropolitan area where rents were extortionate. More than just letting a floor in an empty building, the squatters had to protect their hacklab from police raids and incursions by fascist groups.

Thanks to their embeddedness within a social movement with an anarchist and autonomist outlook, the hackers were furnished with ideological and political training. There was a natural connection with the underground media activities taking place at most social centers; in particular, the broadcasting of pirate radio. Hackers and media activists converged in their defiance of intellectual property, and file sharing presented itself as the latest addition to the pirate arsenal. Like the pirates of legend, squatters legitimized trespassing and appropriation through references to artistic freedom and social redistribution. The aesthetic of the remix, repurposing, and bric-a-brac lent itself easily to trafficking in intellectual property and the reclamation of real estate.

The aforementioned combination of informal sociality, political activism, and hands-on engineering developed into a methodology. A late example is the Hackafou hacklab, which hosted the 2012 Iberian Hackmeeting. This hacklab was situated in Calafou, an old industrial village near Barcelona, turned into a “Post-capitalist, Eco-industrial Colony” by former squatters, where one of the authors lived and participated in the 2010s. In the heyday of this hacklab, hackers and activists could be found there at any hour of the day, coding stoically on flotsam laptops and Frankenstein desktops, falling asleep, exhausted, across a table or in an armchair, throwing a party or playing video games. Hacking was a way of life for many of the participants.

Hacklabs became integrated into the wider hacker culture through a radical reading of free software ideology and practices. The inventor, practitioner, and evangelist of free software, Richard Stallman, articulated a powerful and detailed practical and theoretical critique of intellectual property, arguing that licenses should protect the rights of users rather than producers, while insisting that developers could still profit from software production in various ways. His views have been interpreted as advocating communism—even if sometimes ironically—by a wide range of commentators, from Microsoft CEO Bill Gates (Stallman 2015) to labor activist and political theorist Richard Barbrook (2015). Over the last few decades, Stallman has been touring the world on a never-ending crusade against proprietary software, including appearances at hacklabs and hackmeetings in Spain and Italy.2 Free software was a key component in the ideology and practices of hacklabs. This led to cooperation and conflict with both the free software movement and the squatter movement. Hacklab participants saw a direct connection between the critique of intellectual property articulated by Richard Stallman and the critique of real estate speculation that legitimized occupied social centers. Events in squats, such as hackmeetings, were supported by donations, in the spirit of another staple of occupied social centers, freeshops. In the freeshop, visitors were offered clothes and other items free of charge.3

The alliance between hacklabs, squats, and free software was tested during an event in 2005 that brought a prominent cross-section of free software developers and anarchist hackers into direct contact with each other. Rencontres Mondiales de Logiciel Libre (RMLL), alias Libre Software Meeting, is an annual meeting of free software developers, enthusiasts and users, which combines a conference for the community with outreach promoting free software to a larger audience. When it took place in Dijon, its evening program was hosted by the PRINT hacklab in the Les Tanneries occupied social center under the title Nocturnes. This was a major opportunity to present the anarchist reading of free software to its core participants, advocating an anticapitalist critique of private property as a totality, instead of intellectual property as a specific aberration of the capitalist mode of production. According to recollections in interviews and published reports, the event took both sides by surprise, leaving many free software developers perplexed and some scared, while the hosts were disillusioned by the bourgeois and conservative attitudes of their guests.4 While hacklab participants attempted to radicalize free software developers, their main efforts were directed toward evangelizing free software amongst squatters and anarchists, through setting up network connections and public terminals in squats and providing tech support to the local community. Activists could better identify with the radical reading of free software licenses and appreciated the practical benefits of free software in terms of cost, flexibility, and security. However, the relationship was not without tensions. A string of actions highlighted the frustration of hacklab participants with the slow adoption of free software operating systems within the local social centers.

The Escamot Espiral (the Swirl Commando) was set up by hackers from the Kernel Panic Hacklab in Barcelona. On February 22, 2007, they marched in a demonstration from their base in the La Quimera occupied social center, wearing black balaclavas bearing the eponymous red swirl logo of Debian, the leading community-oriented GNU/Linux operating system distribution, complemented with cheeky devil horns. They stormed into La Torna in the Gràcia neighborhood, an allied Catalan independentist community center. The Commando interrupted the meeting and read their manifesto, declaring that “we’re fed up of being ‘those Linux freaks,’” whose arguments about the social justice and coherence inherent in free software are not heard by the wider movements. They told the assembly of independentists that “enough is enough of alibis. There is no more effort in switching to GNU/Linux than facing the police in demonstrations, [and] enduring evictions.” Therefore, they announced to the terrified audience that “we’re stepping into direct action: any Windows computer we find will be immediately and mercilessly converted to GNU/Linux,” and proceeded to install Debian on the public terminals in the place, wiping out the previous Windows operating system. The action was a light-hearted but strongly felt reminder to their comrades that the cause of free software should be taken as seriously as the other struggles that participants stood for, from free public spaces through to vegan food and Catalan independence. This and two subsequent actions5 demonstrated that hacklabs supported social movements in free spaces, but also brought their own political analysis to the mix.6

Beyond the social and political context, the particular configuration of hacklabs was well adapted to the specific media landscape at the time. In addition to the free software that was ubiquitously used in the hacklabs, IBM-compatible PCs, modems, and wireless routers were part of the standard inventory. The electronics were salvaged from trash bins and occupied buildings and used to build up self-managed infrastructures. The modularity of the IBM-compatible desktop computers lent itself to engineering practices articulated in a context where recycling and stealing were the primary means of accessing resources. Of particular note are wireless routers, which had started to circulate on the retail market as a means of extending connectivity at corporate trade fairs and in office buildings. Yet, 2.4-GHz waves seeped through walls and onto the streets, so that wireless routers could be repurposed to build public networks available to everyone. Community wireless networks, discussed in the chapter on Ronja, spawned in the social centers, and moved outward from there, often making up the backbone of a city’s wireless communications network. Similarly, civilian-grade WEP encryption was used to interfere with the boundaries of the bourgeois private sphere. The same connectivity could provide an uplink for public networks through widely available exploitation of their flawed algorithm. Such exploits were celebrated as a material demonstration of the feasibility of the glitch strategy offered by political cyberpunk. More than anything else, it was the ubiquitous network cables that characterized the visual outlook of these scenes, often doubling as ropes in electrical installations and building material for barricades.

It proved much harder for the hacklabs to accommodate themselves to the next layer of infrastructure that was rolled out on top of their native environment—in particular, smartphones and social media platforms. With the consolidation of corporate power over communications technology, the cutting edge of mainstream media consumption moved away from those practices in which hackers excel, recycling and repurposing. Ultimately, however, it was political decisions and not technological changes that forced the hacklabs into retreat. The decline set in when the squatting movement came under intensified state repression. New eviction laws and toughened police tactics put the squatters, and with them, the social and material basis of the hacklabs, under severe stress.

At a time when the autonomous social movements were suffering defeats and their ideological underpinnings were waning, political cyberpunk paradoxically came to the rescue, lending them another narrative of justification, if not hope. It is paradoxical because it took a dialectic reversal to draw inspiration from a literary genre that distinguished itself by its dystopian approach to the future, characterized by cynicism and pessimism. The combination of Gothic sensibilities, hard-boiled film noir, and science fiction (Whatley 2013; Rapatzikou 2004) proved ideal for a popular movement in retreat. According to this narrative, the survival—if not success—of self-organized collectives depended on the unintended consequences, systemic errors, and chaotic entropy inherent in capitalist progress. The affective, visual, and aural substance of such a configuration was expressed through the aesthetic of the glitch, for which the found materials that filled hacklabs and the broken infrastructure that surrounded them were ideal material.7

Hacklabs were often dimly lit, for both objective and subjective reasons. Objectively, the light installation was one of the many things participants had to take care of on their own. Everything from sourcing electricity, through scavenging cables, to fashioning lampshades were in the hands of the occupants. A staple of squat illumination was Christmas tree lights, especially on staircases, where they could be hung to illuminate several floors from a single socket. The importance of this consists in the fact that sockets were often a scarce resource in the ramshackle buildings. While one of the sites for the ASCII squatted internet cafe in Amsterdam was in a prime corner location, with a shopfront façade on the ground floor, after the next iteration of the eviction-and-occupation cycle, the same collective ended up in a basement. Subjectively, many preferred the darker environments depicted in hacker and cyberpunk movies. Flickering light bulbs due to jittery electrical connections expressed the transitional and liminal nature of temporary autonomous zones. In essence, the limited illumination of hacklabs was not accidental: it stemmed from the material and psychological conditions of the occupants.

HACKERSPACES

The birth of hackerspaces as a social movement can be dated to 2007, when Jens Ohlig and Lars Weiler presented the “hackerspace design patterns” to visitors from the United States, whom they were hosting at C4-Labor, the Chaos Computer Club Cologne Laboratory. The Chaos Computer Club was founded in Hamburg in 1981 as “a galactic community of life forms, independent of age, sex, race or societal orientation, which strives across borders for freedom of information.” Over the years, it grew into the largest hacker organization on the planet, with over 7,700 members and many local chapters as of 2021. Many German hackerspaces emerged from the office and club spaces of these chapters. As recollected in a dedicated book published soon after the legendary events of 2007, “In 2007, a number of meek and lonely hackers from the States went on the Hackers On A Plane adventure going to Chaos Communication Camp and then travelling around Europe visiting hackerspaces. When they arrived at C4 in Cologne, Jens Ohlig and Lars Weiler gave the first presentation of the Hackerspace Design patterns. It’s a document made with the wisdom of doing it wrong in so many wonderful and disastrous ways” (Bre and Astera 2008, 92).

The two went on to speak about the recipe for hackerspaces at the Chaos Communication Camp that summer8 and later at the prestigious annual Chaos Communication Congress at the end of the year (Ohlig and Weiler 2007). However, the birth of a new movement had already been heralded in the canonical medium of US mainstream cyberculture, Wired Magazine (2007), with John Borland reporting from the hacker camp in August. Pioneering spaces such as the c-base in Berlin (established 1995), the aforementioned C4-Labor (established 1998), and Metalab in Vienna (established 2006) served as inspiration for a consistent genre to emerge.

Even before the establishment of the first hacklabs and hackerspaces, a whole range of important and inspirational physical spaces dedicated to the cultivation of cyberculture existed in Europe. A good example is Public Netbase (1994–2006) in Vienna, which was closed by the Haider government in the year of Metalab’s founding, or the Mama Multimedia Institute in Zagreb, Croatia (2000–), which put artists, activists, and geeks in contact with each other and still hosts a hacklab. However, these isolated sites never came together into a popular genre as an ideal-typical social formation that exhibits a high level of consistency across many instances. It is the latter that we are investigating under the rubric of shared machine shops. Such a common understanding was reached at the annual hacker gatherings. It resulted in the proliferation of hackerspaces in northern Europe and North America. The pattern spread to other parts of the world in subsequent years, leading to more than a thousand active spaces today (Hackerspaces Wiki contributors 2020b; Murillo 2019; Davies 2017).

The Chaos Computer Club was established as an activist organization (Denker 2014). It continues to play a role in policy making and enacts high-profile techno-political interventions (Kubitschko 2015). However, the self-definition of hackerspaces at the hackerspaces.org aggregation website highlights tinkering with technology as the sole purpose of hackerspaces: “Hackerspaces are community-operated physical places, where people share their interest in tinkering with technology, meet and work on their projects, and learn from each other” (Hackerspaces Wiki contributors 2020a).

Such a definition is good for identifying a common thread that unites hackerspaces and stands up to empirical scrutiny based on our fieldwork experiences. Whereas many other types of shared machine shops use similar phrases to define themselves, their visitors often find little more than a few machines that identify the innovation potential of the space, coupled with participants writing grant applications on MacBooks. In contrast, hackerspaces are filled with evidence of hardware hacking and other technological experimentation. Members are also more inclined to engage with the materiality of media. However, this definition papers over the diversity of participants—a key aspect of their attraction as sites for community building around technological issues.

That keyholding members will have 24/7 access is taken for granted in the hackerspace genre, but there is also a complementary sense of being a public space in a remarkably broad definition of the concept. For instance, at the aforementioned c-base in Berlin, which is fashioned to resemble a grounded spaceship and alien archaeological site (Fichtner 2015), visitors are DNA scanned at the entrance gate by a mock-sci-fi machine, while a myriad of diverse silhouettes flash up on the screen, only to be told “greetings, human” in a synthetic voice. A corresponding wiki page states that “the lock and the main hall are available to all forms of life” (c-base wiki contributors 2019, para. 27).9 These gatekeeping practices—when interpreted in the wider context of hacker mythology and c-base architecture—manifest antiracist and antispeciesist values, veiled in an ironic commentary on surveillance and control, modernism and progress. It is no surprise, then, that in strict sociological terms, such cosmopolitan—or more accurately, “universal”—aspirations fall short of the reality, as we discuss in more detail later. This style of inclusion draws a largely white, male, able-bodied, middle-aged, city-dwelling, and well-educated crowd.

Meanwhile, “door systems” at many European hackerspaces provide a mechanical and symbolic measure of participation and productivity.10 At Technologia Incognita in Amsterdam, upon entering the space, one faces a big red button at the center of a contraption. Pushing the button lights up eight LEDs around a ship’s wheel drawn in silvery solder on a circuit board the size of a business card. The same circuit board doubles as an educational device that can be purchased as a kit from a vending machine and soldered together according to instructions.11 On the door system installation, the push button is further connected to a single board computer that announces on the internet that the space is open. This is achieved through an API (application programming interface) protocol standardized and aggregated across hundreds of hackerspaces. The real-time opening data is used by various other machines to inform users and gather statistics.

For example, the front page of the hackerspace website now spells “TechInc is OPEN.” Statistics on past opening and closing times are updated on another public web page, and a chatbot announces the event on the IRC channel. Once a key-holding member pushes the button upon entering the hackerspace, unannounced visitors are welcomed to come or go as in any other public space. The door system resembles a time clock at the factory gates, but this gatekeeping device is made to serve a very different purpose. The factory clock enforced the contractually stipulated length of the working day upon employees. The open-door system is designed to enhance the flexibility of the opening hours, so that members can come and go as they please, while allowing the hackerspace to stay open to the public as much as possible. The open-door system integrates hackerspaces into a single material infrastructure that performs the ideal of openness in hacker culture. Even though hackerspaces are organized along the lines of membership clubs, they often double as inclusive and accessible public spaces in their neighborhoods.

The open-door policy notwithstanding, there are numerous limits to the enactment of openness as a political ideal and a social norm in hackerspaces. Three limitations of the universalistic ideals of hackers can be readily detected: firstly, the marked lack of diversity in terms of professional trades and political backgrounds among the members; secondly, class divisions in the surrounding society resurface inside the hackerspace; and thirdly, the extreme gender imbalance, in comparison to which the prominence of queer identities is noteworthy. Although the topics of class, race, and gender have been much debated in hackerspaces and at hacker conferences, the overwhelming majority of participants are still male, white, and middle class (Davies 2017).

Firstly, the point about the diversity of professional trades and political backgrounds can be illustrated with a pair of ethnographic vignettes, originating in 2011 at the London Hackspace and in 2010 at H.A.C.K., the hackerspace in Budapest. One of the authors of this book paid regular visits to the London hackerspace while living and working in the city for an extended year, concurrent with the peak of the Occupy movement. One visit became emblematic of the range of characters who frequented the space. Two Occupy London activists worked on the digital infrastructure of the movement, fixing a wiki installation while discussing how it was being used to organize the camp at Trafalgar Square. The work session took place in the so-called “dirty room,” the dedicated wood and metal workshop. This opens onto the lounge, featuring an assortment of sofas in various conditions of (dis)repair and serving as the main hall of the hackerspace. The lounge hosted the only publicly advertised event that day: a “mind-hacking workshop” where two members were exercising hypnosis in order to broaden their imaginations and experiment with altered body states. The computer room next door was the scene of a private conversation between radio amateurs, one of whom gave a detailed account of his latest professional engagement—sourcing radio equipment for the Metropolitan Police and training the force in its use. In line with the definition above, all these people could be identified as technological tinkerers of some sort. Yet, their professional backgrounds and political attitudes were diverse and sometimes even contradictory. They were no doubt aware of the diversity and contradictions within the membership, since the radio amateur also discussed the presence of Occupy activists in the space. Interestingly, his immediate concerns were starkly practical rather than directly political. He defended the right of activists to use the workshop tools for building contraptions for the occupation but commented on the mess they left behind in the workshop and suspected that some hung out in the space as an alternative to sleeping rough. We return to this observation in a subsequent paragraph on class conflicts.12

The other memorable field experience occurred during a regular information security-themed meetup in Budapest. One of the authors of this book was present at this meeting by virtue of being a regular member and cofounder of the hackerspace. The informal gathering culminated in a heated debate about vulnerable software products used to prop up the digital security infrastructures of some more obscure part of the Hungarian state apparatus. The pizza and beer were sponsored by a small security company providing penetration testing and security certification services to major commercial players in the banking sector. The participants hinted at their backgrounds during the conversation, which went on late into the night. It sounded as though the people at the table included academic staff, secret service operatives, commercial technology consultants, and perhaps even Anonymous activists. What brought these otherwise warring parties together was their interest in information security, which made ideological differences irrelevant in that moment. This political agnosticism of hacker politics has also been observed elsewhere (Coleman 2004).

In fact, the class conflict in the hackerspace movement came to a head simultaneously with the Occupy and Anonymous movements, that is, in 2011 and 2012. Murillo describes the long-term community dynamics, friction, and turbulence that resulted in activists who were sleeping in the space having to call up “middle-class” members to help them out (2019, 213–214). These incidents suggest that Occupy activists and their allies made extensive use of free spaces, including available hackerspaces, which put additional strain on these communities and reinforced existing fault lines. Interestingly, some hackerspaces integrated homeless people into their communities for several years, even though it seems that such initiatives also eventually failed, given the institutional constraints on hackerspaces. “Chess players” have been recognized by hackerspace members from three otherwise very different hackerspaces (Noisebridge in San Francisco, Metalab in Vienna, and Mama in Zagreb, during interviews with Budington, December 26, 2016, Wolf, August 30, 2001, and Mars, April 12, 2014, respectively). This suggests that gatekeeping practices at hackerspaces support subjects who display hacker traits identified by Coleman (2014)—technical virtuosity and the performance of craftiness—regardless of class distinctions. However, Noisebridge later staged a reboot involving closing the space and changing the keys, while the Metalab assembly approved of a plan to convert the only shower into a dark room for developing analogue film, and changes in Mama meant that chess players went elsewhere. The consistency between three otherwise quite different sites—San Francisco, Vienna, and Zagreb—lends further support to the proposition that hackerspaces constitute a genre of their own: a single social formation that can accommodate a diversity of subjects, with notable limitations.

Thirdly, the lack of gender balance and the prominence of queer identities is an enduring feature of hackerspaces. Hacker culture is far removed from the macho mainstream of pop culture—instead it performs an alternative, geek masculinity. In line with the conflict resolution practices in open-source culture and free software projects, the movement forked through the establishment of nonmale—female-identified, trans-forward, and LGBT-friendly—hackerspaces to provide “safer spaces” for technological experimentation and mutual aid (Toupin 2013, 1; 2014). While women consistently report sexist behavior in hackerspaces, hacker scenes have been able, in contrast with other patriarchal milieus, to accommodate nonbinary identities. As hacker anthropologist Gabriella Coleman asks, “Why, for instance, are gender benders, queer hackers, and female trolls common and openly accepted categories, but female participation in technical circles remains low?” (2014, 175). We can answer this question based on our own ethnographic observations. The crux of the matter is that geek masculinity appears to manifest an effective critique of traditional male macho stereotypes, and perhaps even gender binaries as such, but falls short of questioning and subverting the hegemonic gender relations at the heart of patriarchy. This is why it may accommodate queer identities that appear to be compatible with its sensibilities, while failing to include cis-women: a serious political limitation.

Forays by hackerspace members and audiences into institutional politics include two prominent examples. One was the foundation and meetings of the German Pirate Party at the c-base hackerspace in Berlin. The party went on to electoral success, including sending several representatives to the European Parliament. The other was an earlier campaign against software patents coordinated by activists at a European level. It prevented the introduction of patents on algorithms, which had been successfully introduced in the United States. One of the authors of this book has previously argued that hackerspaces today constitute a particularly valuable, materialist approach to the wider project of democratizing science and technology—in sharp contrast, for instance, to consensus conferences (Maxigas 2013). The other author has argued in a different context that, under certain circumstances, hackers’ faith in technological determinism can boost their morale and fortitude, especially when facing up against a stronger opponent (Söderberg 2013). Taken together, these arguments indicate that the political disengagement of hackerspaces is ambiguous. Their largely apolitical outlook aligns well with recuperative logic, but it also doubles as a political and rhetorical tactic in its own right.

“Blinkenlights” is a slang term for the illumination of choice in many hackerspaces. Its industrial origins would lie in the diagnostic LEDs built into mainframe computers and networking equipment such as modems. However, in hackerspaces, the same LEDs are arranged and programmed on purpose to achieve aesthetic effects. Therefore, a dialectical reversal is achieved. LEDs constitute some of the shortest and simplest feedback loops between machines and operators. In industrial environments, these serve to optimize the efficiency of production and, ultimately, increase the profit margin of capital. In hackerspaces, the same instruments serve the reproduction and recreation of workers, in order to prove Levy’s adage from the first definition of hacker ethics: “You can create art and beauty with a computer” (1984, 35). Thus, Blinkenlights may be read as an allegory of workers’ self-management.

ACCELERATORS

In 2005, the venture capitalist, hacker, and entrepreneur Paul Graham delivered a motivational speech on how to start a start-up to the Harvard Computer Society. At this point, his business-minded followers knew him as the developer of early web shops and as a technical author. Hackers and computer scientists read his influential and philosophical essays on what it means to be a hacker, programming techniques, and development methodologies (Graham 1993, 2004a, 2004b). The hacker legend insisted on three factors for successful start-ups: the technical prowess of the founders, which had to be high; the age of the participants, which had to be low; and their business knowledge, which had to be average. He mentioned in the talk that he had always wanted to be an angel investor since he became rich with his first start-up but had never got around to doing it in the previous seven years since he had become rich by selling his start-up to Yahoo! Inc. (Graham 2005).

In his account, Graham (2012) reflected on his own words while driving back home and decided on the same day to fund a large number of undergraduate students with small sums each to found their own companies that summer. The Summer Founders Program would only accept young undergraduates who were real hackers and would teach them about business in exchange for a 7 percent stake in the company. Successful companies would pitch their projects to venture capital firms later. The basic idea remained the same while the initiative grew into Y Combinator, the first instance of the “accelerator” genre of shared machine shops, which produced many globally known companies such as Airbnb and Reddit.

Accelerators can be found throughout the central economies of the world today. They can stand alone as profitable companies, attached to major players in the digital market segment such as Adobe Inc. (XD plug-in) or sponsored by local authorities from the European Union (EIC Accelerator Pilot) to city councils (see Bone et al. 2019). The original Y Combinator program soon moved from Boston to Mountain View, California—in the emblematic Silicon Valley. Paul Graham credits the move to his experience at Foo Camp that took place near Berkeley, California, an annual hacker convention organized by O’Reilly Media, the influential software development book publisher. Even though accelerators are a global phenomenon today, they still look to the Silicon Valley cluster of IT companies as a role model.

This may all sound very boring to readers who enjoyed the previous sections. It may not be at all evident that accelerators connect to the confrontational and anarchist politics of hacklabs or the do-it-yourself ethos of hackerspaces. We count accelerators among the list of shared machine shops because they explicitly draw upon the legitimacy and tropes of hacker culture, while targeting the same demographic group that could otherwise have ended up joining a hackerspace (i.e., graduate students during their time at technical university). The culture of hackers has been deconstructed and rebuilt from the ground up in order to create a climate chamber in which venture capital can thrive.

The narratives that hackers like to tell about themselves could, with only minor adjustments, be made to fit the new bill. As mentioned in the previous chapter on the open-source desktop 3D printer, engineering culture displays an ambivalent attitude toward the price mechanism. On the one hand, engineers decry the irrationality of allowing prices to dictate industrial activity, as this often leads to wasted expenditure and suboptimal output. On the other hand, price is generally accepted by engineers as a neutral gauge of the cost-efficiency, by which is understood superiority, of an engineering solution. On balance, the engineering profession has been more vexed about bureaucracy than markets. Catering to this disposition of engineering students was a small task. Hence, the market can be presented as a polling station for consumer satisfaction and a mechanism by which technology is democratized. The one thing that prevents consumers from accessing better products is incumbent interests that rely on monopoly practices and crony politics in order to stay on top. From this narrative, it follows that the role of the good guy is played by small entrepreneurs with big ideas who want to cut into the relevant market segment. Young engineering graduates with seed money can thus pretend to have a share in the rebellious and outlaw imagery of the computer underground.

The freedom allowed by seed money from Y Combinator is similarly ambiguous in terms of property relations. The first call (Y Combinator 2012b) and the application form (Y Combinator 2012a) emphasize that what the initial investment allows is merely for participants to move into a rental apartment in Berkeley and buy food for themselves during the summer break. This is in line with Graham’s theory that high-level programming languages and consumer-grade network connectivity have brought down the cost of establishing start-up companies in the lucrative and attractive IT sector. However, it is also in line with the tendency of capital to provide, barely, for the reproduction of workers, relegating social mobility to the realm of possibilities, where it serves to justify the social domination of capitalists over the rest of society. In practice, the few examples of “unicorns”—unusually successful IT start-ups—produced by Y Combinator and similar accelerators legitimize their wider economic functions. The latter might boil down to launching into and maintaining excess working in orbit above the value-producing sections of the market economy, so that they neither rely on unemployment subsidies nor contribute to overproduction that would bring inflation.

The entrepreneur-hacker-workers of Y Combinator are granted the freedom to work whenever and wherever they want, yet are guided through the modulation of their life conditions to converge on the aforementioned apartments in Berkeley. Graham celebrates the rigor and flexibility of young graduate students for enabling them to work hard for the success of their own company in a self-directed way (Graham 2005). What he describes is easily recognized in Marxist terms as the formal subsumption of self-motivated labor. Accelerators bring into the service of capital the methodology of collaboration once developed by hacklabs and hackerspaces, to reduce institutional oversight—but in the hope of increasing productivity.

Y Combinator’s office in Mountain View, California, situates the venture at the heart of the Silicon Valley capital, as part and parcel of a booming economic miracle. The dilapidated postindustrial buildings where hacklabs flourished are nowhere to be seen—neither are accelerators hosted in neighborhoods in the process of revitalization where hackerspaces once found cheap rents. In fact, the main opportunity offered to participants by Y Combinator is to insert themselves into the networks that constitute the industrial cluster of Silicon Valley.

In line with the formal subsumption of the legacy of hacklabs and hackerspaces, the Y Combinator company headquarters where events of the “start-up school” take place feature a few distinct—but easy to install—markers to show that it is not your boring average office. Clean orange walls mimic the color of Y Combinator’s logo and enable audiences to identify the location of photos of participants taken on the premises. In contrast, hacklabs made no pretense of decoration, while hackerspaces fall at the other end of the spectrum with their elaborate Blinkenlights displays. The recycled infrastructures of squats are difficult to keep clean, and in hackerspaces cleaning is left to the (predominantly male) membership—but accelerators hire staff to clean and change failing light bulbs.

Accelerators are lit well and evenly, like any other office space or production plant. Lights are regularly changed by maintenance workers, who are responsible for stabilizing patterns of illumination. Illumination has always been a key consideration in the layout of the factory. It is essential for workers to be visible so that managers can oversee them, and visibility of the machines is essential for workers to operate them with maximum productivity. Lights go on and off at once in sizable sections of the space, in the same rhythm as the cycles of the eight-hour working day and the movement of the sun around the earth. Accelerators borrowed freely from the methodologies and cultural tropes of earlier generations of shared machine shops, but only those that expedited entrepreneurial ends. Blackouts and energy shortages were commonplace in the original shared machine shops. They contributed to the ambiance of the place, while reinforcing at an aesthetic level a shared opposition to living inside an office cubicle. Understandably, this was not a feature of hacklabs and hackerspaces that the designers of accelerators wanted to emulate.

FUNCTIONAL AUTONOMY ADVANCED AND RELINQUISHED

Earlier in this book, we identified three pillars of functional autonomy as key for enabling hackers to articulate critical perspectives on science and technology and, concurrently, for them to detect and resist recuperation attempts. These pillars are technical expertise, shared values, and historical memory. Shared machine shops are privileged sites for the articulation of technical expertise. They provide a social milieu within which technical expertise can circulate and develop at arm’s length from the predominant institution in society where such knowledge is reproduced: the engineering curriculum. Equally important, shared machine shops preserve and expand the material infrastructure upon which the critical engineering practices of hackers depend.

Shared machine shops serve many more purposes than just facilitating the learning process and providing its members with technical skills. Informal socializing, gossiping, partying, and so on strengthen the ties of solidarity and build a cohesive identity among the participants, both within the local hackerspace and in relation to hacker culture at large. In the process, the hackers adopt a shared value system. The social aspect is most clearly forthcoming in the early genres of shared machine shops, hacklabs and hackerspaces, but also holds true for makerspaces and FabLabs. Even in the most recuperated manifestation of shared machine shops (i.e., the accelerators), there are social and ideological components in addition to the instrumental purpose of the setting. Participants understand themselves and represent their mission in opposition to what they identify as mainstream narratives about technological—and, therefore, political—exclusivity. The ambition of democratizing technology is embraced by all the genres of shared machine shops and constitutes a minimum of shared values.

In our assessment, the weakest link in the constitution of shared machine shops is the transmission of historical memory. Having a common understanding of past events and their significance for one’s own collective existence in the future is indispensable if hackers are to maintain their functional autonomy over the long haul. We argue that the decisive moment of memory loss occurred in connection with the transition from hacklabs to hackerspaces. Soon after the latter movement was launched, it forgot, not to say repressed, the memory of its origins and, subsequently, the lessons that had been learned by the preceding generation of hackers. Thus, the hackerspace movement was ripe for future waves of recuperation, which took place in multiple ways and resulted in an explosion of depoliticized shared machine shop genres. Makerspaces, FabLabs, Tech Shops, and so on can be adequately described as successive steps toward the full consummation of a recuperative logic, the endpoint being the accelerators.

This observation can be made without denying the contrasting testimonies coming from participants. Hackers who contribute to “any” genre of shared machine shop may legitimately assert their experience of being part of something special: an empowering environment that challenges institutional control and managerial oversight. All genres of shared machine shops promote technical literacy and thus have the potential to contribute to expanded worker autonomy. However, when all the successive iterations of shared machine shops are placed next to one another in a longer time series, a trend becomes evident. The potential for generating critical engineering practices steadily shrinks, leaving a correspondingly larger space for capital to put the collective to work.

At the outset of this chapter, we made an adventurous methodological proposition with reference to satellite images of the earth, where brightness indicates areas of economic activity and boom times, while deprived areas and downturns in the business cycle are detectable in a dimming of the light emissions. Our spin on this popular-culture trope is that patterns of indoor lighting in shared machine shops indicate the extent to which the space in question has been integrated into the circuits of capital accumulation. The light signature of hacklabs corresponds to a stochastic pattern that stems from recycled infrastructure and self-maintained hardware. These material conditions in turn speak about the marginal position of hacklabs and house occupations vis-à-vis surrounding society. As for hackerspaces, the ambiance of those places is in large part created by illuminations programmed to perform eccentric geometric and temporal patterns. The Blinkenlight aesthetic is a display of workers’ control. Diagnostic lights, originally used to supervise the production flow in the factory, have been repurposed for aesthetic pleasure and playfulness, announcing to the world the self-organizing splendor of hackers. Finally, the illumination fingerprint of accelerators is barely distinguishable from that of a conventional office space. The accelerator’s light emissions ebb and flow with the same pulse as regular office hours.

Taken together, the visual narratives of illumination patterns from these three genres of shared machine shops tell the story of their gradual reintegration into capitalism. The shadowy abode of the hacklab testified to the social marginality of its denizens. In hackerspaces, its participants expressed their self-managed cultural distinctiveness by making a show out of the lights. The accelerator, finally, has blended with and become indistinguishable from its surroundings, even in terms of indoor lighting.

THE CONTEXT OF GENTRIFICATION AND CAPITALIST RESTRUCTURING

In the following, we zoom out to the third time horizon in our analytical scheme, with the ambition of substantiating the claim previously made, that we can observe a tendency of development within the movement of shared machine shops toward the full consummation of the recuperative logic. This narrative is framed by two systematic ruptures in capitalism. As indicated in the section on the prehistory of shared machine shops, the story begins with the economic crisis of the 1970s, in the aftermath of which came deindustrialization and the outsourcing of industrial production. The story closes with the consolidation of urban regeneration programs, which began initially in the 1990s with the rhetoric about “creative cities,” but picked up speed during the 2010s, this time under the banner of the “smart city.” The movement of shared machine shops can be situated in between these temporal landmarks, the fall of the industrial city and the rise of a city of finance and media consumption.

Each genre of shared machine shops can be related to different conceptions of the city. This follows simply from the fact that physical spaces within a built environment will be subject to trends in city planning. Urban development policy is consequential for shared machine shops in more indirect ways as well. The social and economic conditions of the immediate vicinity will be reflected in what goes on inside those buildings, as suggested by hackerspaces sheltering Occupy activists and chess players. Above and beyond the empirical case for making a digression into gentrification processes, this reference lends support to two key theoretical claims in this chapter. Firstly, speculation in real estate demonstrates how value could be derived from secondary activities and interactions that took place outside of the formal wage relation and despite the actors having different goals in mind. Secondly, we can diagnose the progress of recuperation by reference to the different political agendas that the different genres of shared machine shops have enacted within urban regeneration plans.

Hacklabs emerged during the 1990s, for the most part concentrated within regions in southern Europe that had suffered from deindustrialization and capital flight. Following urbanologists Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin (2001), media theorists Plantin and others point to the retreat of modernist and infrastructural ambitions during this period as constitutive of the symbolic meanings and social formations of an early computer culture (2018, 299–300). A more palpable consequence of the economic downturn was an abundance of empty buildings in city centers. In combination with an underperforming urban policy environment, the stage was set for a movement of occupied social centers to blossom (López 2013).

In league with squatters, hackers filled the empty buildings, catered to unfulfilled social needs in their neighborhood communities, and exploited underdeveloped infrastructures that had been abandoned after the first wave of neoliberal urbanization. The annual hackmeetings, the hacklabs, and legendary events, such as Nocturnes and the actions of Escamot Espiral (detailed above), took place in occupied social centers. The squatting movement provided the material and cultural conditions for hacklabs to emerge. On the downside, as has become evident after this movement fell away, the autonomist milieu also set the historical limits for the expansion of a highly politicized form of hacking.

The instigation of hackerspaces, and much the same can be said about makerspaces and FabLabs too, was predicated upon the struggle for access to the city that had been waged by squatters and hackers during the previous years. In their confrontations with city halls, occupied social centers were adamant about their cultural and social contributions to their neighborhoods. This community service was, however, entangled with a political agenda: fierce opposition to neoliberal policies, advocacy for free spaces for artists and activists, and campaigns demanding affordable housing for local residents. In the same period, municipal councils courted Richard Florida’s rhetoric about “creative cities” (2005). Under this auspice, artists and community organizers were instrumentalized for the purpose of revitalizing formerly neglected, inner-city quarters. Working-class neighborhoods and factory sites were refashioned and gentrified, in the first step by setting up artists’ workshops and offices of community associations. Hackerspaces fitted the bill.

During a transitional period, hackerspaces had an easy time securing tenant contracts on favorable terms in central locations. The underlying agenda of the practice is suggested, for instance, by the name with which city administrators and entrepreneurial artists refer to such places. In the Netherlands, they are called a broedplaats—that is, a “breeding ground” or “hatching place.” It is understood that the broedplaats is only a temporary arrangement, to be terminated when the neighborhood becomes ripe for more rentable investments. The founding decision of hackerspaces, in contradistinction to hacklabs, to self-organize within the confines of legal and institutional arrangements, makes them prone for enrollment into neoliberal urban policies. In some instances, this practice is directly pitted against the autonomous movement and, subsequently, against the hacklabs. A case in point is the situation of some hackerspaces in the Netherlands—such as Frack in Leeuwarden or Nurdspace in Wageningen—which were hosted in buildings managed by antisquatting companies. These companies offer precarious contracts for tenants in small parts of otherwise empty buildings in order to protect the property from squatters.

In the introduction to this book, we noted that recuperation often takes place behind the backs of participants. Something familiar acquires a new meaning that is diametrically opposed to what it once stood for, while the outward appearance of the thing remains the same as always. This is exactly what has happened when the soldering irons, the mandatory do-it-yourself slogans, and free software advocacy, which used to be part of the inventory of occupied social centers, resurface in a community space whose ultimate purpose, as stipulated in the tenant contract, is to protect and nurture the interests of real estate developers.

The policy discourse about “creative cities” has largely been supplanted by talk about “smart cities.” Creativity was the watchword in the promotion of broadband connectivity a decade ago. The communication infrastructure was imagined as laying the foundations for unlimited and ubiquitous expansion in directions that could not be specified in advance by policy makers. In contrast, 5G networks are deployed under the auspices of smart cities, where the whole environment is designed from the ground up with specific business and administrative applications in mind, integrating everything from autonomous vehicles to crowd control. Where creative city evangelists rallied around the entrepreneurial, small-is-beautiful ethos as the vector of economic development, smart city lobbyists construct a rationalist, top-down narrative of technocratic control (Luque-Ayala and Marvin 2020).

Accelerators fit perfectly into this latest vision of the city. In doing so, however, their advocates mobilize the technological imaginaries, material practices, and tropes of hacker culture and previous generations of shared machine shops. The DIY imperative, which merged with direct action in hacklabs, and was reimagined as “do-ocratic governance” in hackerspaces, remerges as agile development practices in accelerators and similar organizations (Irani 2015b). The name “Y Combinator” alludes to a design pattern from functional programming, a programming paradigm that is strongly attached to the alternative engineering culture of hacking (the canonical reference is Abelson and Sussman 1996). While functional programming languages and techniques are seldom used in the industry, hackerspaces host functional programming meetups and cultivate this paradigm.13 As mentioned above, Y Combinator founder Paul Graham is a notable functional programmer who has published on the topic (1993), but the legacy of hacker culture was quickly watered down in the hands of his many acolytes. Hackerspaces supplanted hacklabs while preserving some of their predecessors’ political engagements. The recuperation of hackerspaces proceeded through structural conditions and neoliberal policy making that engulfed the affordances and foresight of individual members of those spaces. Accelerators, in contrast, recuperate hacker culture by design.