Water Rights: The State, the Market, the Community

Who does water belong to? Is it private property or a commons? What kind of rights do or should people have? What are the rights of the state? What are the rights of corporations and commercial interests? Throughout history, societies have been plagued with these fundamental questions.

We are currently facing a global water crisis, which promises to get worse over the next few decades. And as the crisis deepens, new efforts to redefine water rights are under way. The globalized economy is shifting the definition of water from common property to private good, to be extracted and traded freely. The global economic order calls for the removal of all limits on and regulation of water use and the establishment of water markets. Proponents of free water trade view private property rights as the only alternative to state ownership and free markets as the only substitute to bureaucratic regulation of water resources.

More than any other resource, water needs to remain a common good and requires community management. In fact, in most societies, private ownership of water has been prohibited. Ancient texts such as the Institute of Justinian show that water and other natural sources are public goods: “By the law of nature these things are common to mankind—the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shore of the sea.”1 In countries like India, space, air, water, and energy have traditionally been viewed as being outside the realm of property relations. In Islamic traditions, the Sharia, which originally connoted the “path to water,” provides the ultimate basis for the right to water. Even the United States has had many advocates for water as a common good. “Water is a moving, wandering thing, and must of necessity continue to be common by the law of nature,” wrote William Blackstone, “so that I can only have a temporary, transient, usufructuary property therein.”2

The emergence of modern water extraction technologies has increased the role of the state in water management. As new technologies displace self-management systems, people’s democratic management structures deteriorate and their role in conservation shrinks. With globalization and privatization of water resources, new efforts to completely erode people’s rights and replace collective ownership with corporate control are under way. That communities of real people with real needs exist beyond the state and the market is often forgotten in the rush for privatization.

Water Rights as Natural Rights

Throughout history and across the world, water rights have been shaped both by the limits of ecosystems and by the needs of people. In fact, the root of the Urdu word abadi, or human settlement, is ab, or water, reflecting the formation of human settlements and civilization along water sources. The doctrine of riparian right—the natural right of dwellers supported by a water system, especially a river system, to use water—also arose from this concept of ab. Water has traditionally been treated as a natural right—a right arising out of human nature, historic conditions, basic needs, or notions of justice. Water rights as natural rights do not originate with the state; they evolve out of a given ecological context of human existence.

As natural rights, water rights are usufructuary rights; water can be used but not owned. People have a right to life and the resources that sustain it, such as water. The necessity of water to life is why, under customary laws, the right to water has been accepted as a natural, social fact:

The fact that right over water has existed in all ancient laws, including our own dharmasastras and the Islamic laws, and also the fact that they still continue to exist as customary laws in the, modern period, clearly eliminates water rights as being purely legal rights, that is, rights granted by the state or law.3

Riparian Rights

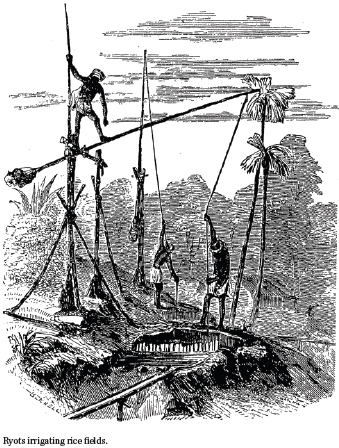

Riparian rights, based on concepts of usufructuary rights, common property, and reasonable use, have guided human settlement all over the world. In India, riparian systems have long existed along the Himalaya. The famous grand Anient (canal) on the Kaveri at the Ullar River dates back a thousand years and is believed to be the oldest hydraulic structure to control the flow of rivers in India. It is still functioning. In the northeast, old riparian systems known as dongs guide the use of water. In Maharashtra, conservation structures were known as bandharas.

The ahar and pyne systems of Bihar, where an unlined inundation canal (pyne) transfers water from a stream into a catchment basin (ahar), also evolved from a riparian doctrine. Unlike modern Sone canals built by the British, which have failed to meet the needs, of the people, the ahars and pynes still provide water to peasants. In the United States, riparian systems were introduced by the Spanish, who had brought them from the Iberian Peninsula.4 These systems were adopted in Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona, as well as the eastern settlements.

Early riparian principles were based on the notion of sharing and conserving a common water source. They were not attached to property rights. As historian Donald Worster notes:

In ancient times, the riparian doctrine was less a method of ascertaining individual property rights and more the expression of an attitude of non-interference with nature. Under the oldest form of the principle a river was to be regarded as no one’s private property. Those who lived along its banks were granted rights to use the flow for natural purposes like drinking, washing, or watering their stock, but it was a usufructuary right only—a right to consume so long as the river was not diminished.5

Even European colonists who first settled in the eastern United States adhered to these basic tenets. But as the western part of the country began to be inhabited, usufructuary rights were no longer prevalent. The riparian concept was instead believed to have emerged from English common law and consequently centered around individual property ownership. “The men and women who settled the American West did not belong to that older world … [They] rejected the traditional riparranism,” writes Worster. “Instead, they chose to set up over most of the region the doctrine of prior appropriation because it offered them a greater freedom to exploit nature”6 Universal water rights were thus severely curtailed.

Cowboy Economics: The Doctrine of Prior Appropriation and the Advent of Privatization

It was in the mining camps of the American West that the cowboy notion of private property and the rule of appropriation—Qui prior estin tempore, potior est in jure (He who is first in time is first, in right)—first emerged. The doctrine of prior appropriation established absolute rights to property, including the right to sell and trade water. New water markets blossomed and soon replaced natural water rights and the value of water was determined by the monopolistic first settlers. Prior appropriation “gave no preference to riparian landowners, allowing all users an opportunity to compete for water and to develop far from streams.”7

The cowboy sentiment “might is right” meant that the economically powerful could invest in capital-intensive means to appropriate water regardless of the needs of others and the limits of water systems. This frontier logic granted the first appropriator an exclusive right to the water. Latecomers could appropriate water on the condition that prior rights were honored first. Cowboy economics permitted the diversion of water from streams to be used on nonriparian lands. If the appropriator did not use the water, he was forced to forfeit his right.

The cowboy logic allowed the transfer and exchange of water rights among individuals, who often disregarded water’s ecological functions or its functions beyond mining. Although rights were based on first settlement, the true first settlers—Native Americans—were denied water appropriation rights. Miners and colonizers, assumed to be the first inhabitants, were granted all rights to use the water sources.8

Disregard for the limits of nature’s hydrological cycle meant that rivers could be drained and polluted by mining waste. Disregard for the natural rights of others meant that people were denied access to water, and regimes of unequal and nonsustainable water use and water-wasteful agriculture began to spread across the American west.

Contemporary Cowboy Economics

The current push to privatize common water sources had its foundation in cowboy economics. Champions of water privatization, such as Terry Anderson and Pamela Snyder of the conservative Cato Institute, not only acknowledge the link between current privatization efforts and cowboy water laws, but also look at the earlier Western appropriation philosophy as a model for the future:

From the western frontier, especially the mining camps, came the doctrine of prior appropriation and the foundation of water marketing. This system provided the essential ingredients for an efficient market in water wherein property rights were well-defined, enforced and transferable.9

The current push to reintroduce and globalize the lawlessness of the frontier is a recipe for destroying our scarce water resources and for excluding the poor from their water share. Parading as the anonymous market, the rich and powerful use the state to appropriate water from nature and people through the prior-appropriation doctrine. Private interest groups systematically ignore the option of community control over water. Because water falls on earth in a dispersed manner and because every living being needs water, decentralized management and democratic ownership are the only efficient, sustainable, and equitable systems for the sustenance of all. Beyond the state and the market lies the power of community participation. Beyond bureaucracies and corporate power lies the promise of water democracy.

Water as a Commons

Water is a commons because it is the ecological basis of all life and because its sustainability and equitable allocation depend on cooperation among community members. Although water has been managed as a commons throughout human history and across diverse cultures, and although most communities manage water resources as common property or have access to water as a commonly shared public good even today, privatization of water resources is gaining momentum.

Prior to the arrival of the British in south India, communities managed water systems collectively through a system called kudimaramath (self-repair). Before the advent of corporate rule by the East India Company in the 18th century, a peasant paid 300 out of 1,000 units of grain he or she earned to a public fund, and 250 of those units stayed in the village for maintenance of commons and public works.10 By 1830, peasant payments rose to 650 units, out of which 590 units went straight to the East India Company. As a result of increased payments and lost maintenance revenue, the peasants and commons were destroyed. Some 300,000 water tanks built over centuries in pre-British India were destroyed, affecting agricultural productivity and earnings.

The East India Company was driven out by the first movement for independence in 1857. In 1858, the British passed the Madras Compulsory Labor Act of 1858, popularly known as the Kudimaramath Act, mandating peasants to provide labor for the maintenance of the water and irrigation systems.11 Because kudimaramath was based on self-management and not coercion, the act failed to mobilize community participation and to rebuild the commons.

Self-managed communities have not just been a historical reality; they are a contemporary fact. State interference and privatization have not wiped them out entirely. In a nationwide survey covering districts in dry tropical regions in seven states, N. S. Jodha finds that the most basic fuel and fodder needs of the poor throughout India continue to be satisfied from common property resources.12 Jodha’s studies of commons in the fragile Thar desert also reveal that village community councils still adjudicate grazing rights: institutional rules and regulations determine periods of restricted grazing, the rotational patterns for grazing, the numbers and types of animals to be grazed, the rights to dung and fuel wood collection, and the rules for lopping trees for green fodder. Village councils also appoint their own watchmen to ensure that no community member or outsider breaks the rules. Similar rules exist for maintenance of wells and tanks.

Tragedy of the Commons

John Locke’s treatise on property effectively legitimized the theft of the commons in Europe during the enclosure movements of the 17th century. Locke, son of wealthy parents, sought to defend capitalism—and his family’s massive wealth—by arguing that property was created only when idle natural resources were transformed from their spiritual form through the application of labor: “Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state that Nature hath provided and left in it, he hath mixed his labor with it, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property”13 Individual freedom was dependent upon the freedom to own, through labor, the land, forests, and rivers. Locke’s treatises on property continue to inform theories and practices that erode the commons and destroy the earth.

In contemporary times, water privatization is based on Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons, first published in 1968. To explain his theory, Hardin calls on us to imagine a scenario:

Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. Such an arrangement may work reasonably satisfactorily for centuries because tribal wars, poaching, and disease keep the numbers of both man and beast well below the carrying capacity of the land. Finally, however, comes the day of reckoning, that is, the day when the long-desired goal of social stability becomes a reality. At this point, the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy.14

Hardin assumes that commons were socially unmanaged, open-access systems with no ownership. And Hardin sees the absence of private property as a recipe for lawlessness.

Although Hardin’s theory about the commons has gained tremendous popularity, it is has several holes. His assumption about commons as unmanaged, open-access systems stems from the belief that management takes effect only in the hands of private individuals. But groups do manage, themselves, and commons are regulated rather well by communities. Moreover, commons are not open-access resources as Hardin proposes; they in fact apply the concept of ownership, not on an individual basis, but at the level of the group. And groups do set rules and restrictions regarding use. Regulations of utility are what protect pastures from overgrazing, forests from disappearing, and water resources from vanishing.

Hardin’s prediction about the doom of commons has at its center the idea that competition is the driving force in human societies. If individuals do not compete to own property, law and order will be lost. This argument has failed to hold ground when tested in large sections of rural societies in the Third World, where the principle of cooperation, rather than competition, among individuals still dominates. In a social organization based on cooperation among members and need-based production, the logic of gain is entirely different from those in competitive societies. Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons misses the critical point that under circumstances in which common lands cannot even support the basic needs of the population, a tragedy is inevitable—with or without competition.

Communities and Commons

In the upper reaches of the Rio Grande Valley in Colorado, water is still managed as a commons. I had the opportunity to visit San Luis, home of traditional acequia systems (gravity-driven irrigation ditch) that nurture soils, plants, and animals. I was there to offer solidarity to the local communities engaged in a major struggle to defend the commons and the oldest system of water rights in Colorado. What the irrigation ditches produce is not merely a market commodity but a denseness of life. “The ditches make a lot of plant life possible in what is really a cold, barren desert,” says Joseph Gallegos, a fifth-generation farmer working on ancestral lands in San Luis. “More plants means that the wildlife—birds and mammals—have a home. The ecologists call this biodiversity. I call it life, terra y vida.”15

When the water of the Rio Grande is auctioned to the highest bidder, it is taken away from the agri-pastoral community whose rights to the water are tied to the responsibility of maintaining a “watershed commonwealth.”16 Markets fail to capture diverse values, and they fail to reflect the destruction of ecological value. Water that replenishes ecosystems is considered water wasted. Joseph Gallegos raises an important point when he asks:

Whose point of view is this? The cottonwood trees that line the acequia banks don’t think the leaking water is wasted. Nor do the birds and other animals that live in the trees. The ditches create habitat niches for wildlife, and that is a good thing for the animals and the farmers. It is not wasteful, unless of course you are an urban developer greedily looking for more water for the cities’ maniacal growth needs. The gringo treats water like a commodity. You know the saying, “In Colorado water flows uphill, towards money.”17

When money determines value and courts get involved, common resources are stripped from farmers and lost to private companies. And, as Devon Peña points out,

The attack on common property rights involves the legal codification of production that produces violent but legally sanctioned invasions, enclosures, and expropriations of space. The law itself violates the integrity of places as habitat for mixed communities of humans and non-humans.18

This is exactly what transpired in the Rito Seco Watershed in Colorado, when courts allowed the Batde Mountain Gold Mine to transfer water from agriculture to industrial use.

Community Rights and Water Democracies

Under conditions of scarcity, sustainable systems of water management evolved from the idea of water as commons passed on from generation to generation. Labor in conservation and community building became the primary investment in water resources. In the absence of capital, people working collectively provided the major input or “investment” in water works. As Anupam Mishra of the Gandhi Peace Foundation observes:

The ways of collecting the drops of Palar, i.e., of rainfall, are as unending as the names of clouds and drops. The pot like the ocean is filled up drop by drop. These beautiful lessons are not to be found in any textbook but are actually couched in the memory of our society. It is from this memory that the shrutis of our oral traditions have come…. The people of Rajasthan did not entrust the organisation of such a boundless work to either the central or federal government, not even to what in modern parlance is termed as the private sphere. It is the people themselves who in each house, in each village, gave fruition to this structure, maintained it, and further developed it.

“Pindwari” is to help others through one’s effort, one’s labour, one’s hard work. The drops of sweat streaming down the brow of the people of Rajasthan continue to flow so as to collect the drops of rain.19

Traditional water systems based on local management were insurance against water scarcity in drought-prone regions of Gujarat. These systems were managed mainly by village committees. In the event of floods, famines, and other calamities, the king also helped; the role of a central authority was, therefore, primarily in disaster mitigation. Local institutions in water management included farmers’ associations, local irrigation functionaries, local irrigation technicians, the village water associations, and the community labor system, maintained by contributions from each family.

In India, farmers’ associations for the construction and maintenance of water systems were once widespread. In Karnataka and Maharashtra the associations were known as panchayats. In Tamil Nadu, they were called nattamai, kavai maniy am, nir maniyam, oppidi sangam, or eri variyam (tank committee). Tanks and ponds often served more than one village, and in such cases representatives from each village or farmers’ association ensured democratic control. These committees could also collect tank dues and taxes from users. Lands were also donated, especially for financing capital expenditures on waterworks.

Village water systems required irrigation functionaries who looked after the day-to-day operation of irrigation systems. In the Himalayas, where kuhls served community irrigation needs, irrigation managers were called kohlis. In Maharashtra, they were known as patkaris, havaldars, and jogalaya. In Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, they were known as nirkatti, nirganti, nirpaychi, niranikkans, or kamkukatti.

To ensure neutrality, nirkattis were chosen from the landless caste—the Harijans—who were granted autonomy from landowners and caste groups. Only Harijans held the power to close and open the tanks or vents. Once the farmers laid down the rules of distribution, no individual farmer could interfere, and those who did could be fined. This protection of the associations from the economically powerful ensured water democracy.

Compensations were based on investments of one’s own labor and could not be substituted by capital or by others’ labor. In South India, collective labor investment was the primary investment in the construction and maintenance of village water systems known as kudimaramath. Each able-bodied person was required to help maintain and clean channels. Nirkattis also summoned farmers to clean the supply and field channels. The ancient economic treatise, Arthasastra, included certain punishments for defaulters from any kind of cooperative construction. Violators were expected to send their servants and bullocks to carry on their work and to share the costs, without laying any claim to the return.

The self-management systems suffered when the government took control over water resources during British rule. Community ownership was further eroded with the emergence of bore wells and tube wells, which made individual farmers dependent on capital. Collective water rights were undermined by state intervention, and resource control was transferred to external agencies. Revenues were no longer reinvested in local infrastructure but diverted to government departments.

Community rights are necessary for both ecology and democracy. Bureaucratic control by distant and external agencies and market control by commercial interests and corporations create disincentives for conservation. Local communities do not conserve water or maintain water systems if external agencies—bureaucratic or commercial—are the only beneficiaries of their efforts and resources.

Higher prices under free-market conditions will not lead to conservation. Given the tremendous economic inequalities, there is a great possibility that the economically powerful will waste water while the poor will pay the price. Community rights are a democratic imperative—they hold states and commercial interests accountable and defend people’s water rights in the form of decentralized democracy.

The Right to Clean Water versus the Right to Pollute

Prior to passage of the Water Act of India in 1974, almost all judicial decisions were in favor of polluters. In addition to being protected by law, polluters also had more economic and political power than ordinary citizens. They were even more successful in using the legal processes in their favor. When the impact of industrial pollution was not severe or when industrialization was seen as a symbol of progress, courts tended to uphold the rights of the industrialists to pollute water as exemplified in a number of cases: Deshi Sugar Mills v. Tups Kahar, Empress v. Holodhan Poorroo; Emperor v. Nana Ram; Imperatix v. Neelappa; Darvappa Queen v. Vittichakkon; Reg v. Partha; and Imperatix v. Hari Baput. As water pollution intensified with the spread of industrialization, it could be handled only through criminal or penal sanctions. However, the courts alone could not protect people’s right to clean water.

By the 1980s, as the threat from pollution increased, the right to clean water had to be defended as a fundamental right. The Supreme Court of India introduced a new principle of environmental rights in the famous case Ratlam Municipality v. Vardhichand. The municipality had to remove public nuisances, whether it had the financial capability to do so or not. Ratlam established a new type of natural right and recognized customary rights as a constitutional guarantee. But even after Ratlam and the Water Act, the big polluters were not brought under the law. In most cases, the Central Water Pollution Board was against small factories.20

In the industrial world, antipollution regulations were introduced primarily to clean up rivers. In 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio, which served as a dump site for industries, was so contaminated by chemicals that it caught fire. In 1972, the United States passed the Clean Water Act, which established that no one had a right to pollute water and that everyone had a right to clean water. Before the passage of the law, water pollution was handled as a matter of common law involving trespassing and nuisance. The act set the goal of rendering the waters fishable and swimmable by 1983, and eliminating discharges of water pollutants by 1985. Since the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, US pollution from point sources has been dramatically reduced, showing the power of regulation in pollution control.

In 1977, as a result of pressure from industry, the focus in the United States shifted from control-point discharge regulation to water quality standards. Tacitly, this shift marked a move away from pollution as a violation to pollution as permissible. Companies attempted to reintroduce the right to pollute through back-door efforts such as tradable pollution rights or tradable discharge permits (TDPs). Although TDPs have faced resistance from environmentalists, they still remain a popular market myth for solving pollution problems.

Supporters of the free market promote TDPs as an alternative to the “command-and-control” of environmental regulation. However, trade in pollution is also government sanctioned. As free-market advocates Snyder and Anderson admit, “Tradable pollution rights are essentially an assignment by a governmental agency of a right to discharge a specified level of pollution into a water body or water course.”21 The government also sets pollution standards, albeit on the basis of a fictitious “bubble,” an imagined boundary covering a designated area.

It is not surprising that pollution permits are ecologically blind. They merely consider “incentives for gains from trade.” If pollution control costs are low, an industry will sell discharge rights, and if costs are high, an industry will buy discharge rights. While such cost-benefit analysis might appear to create trade advantages, this market of pollution is ecologically dangerous.

Trade in pollution permits violates ecological democracy and people’s right to clean water on several counts. It changes the role of governments from protector of people’s water rights to advocate of polluters’ rights. Governments assume regulatory roles that are anti-environment, anti-people, and pro-polluter industry. TDPs exclude nonpolluters and ordinary citizens from an active democratic role in pollution control, since the trade in pollution is restricted to polluter industries.

Big Polluters: Old and New

The struggle between the right to clean water and the right to pollute is the struggle between the human and environmental rights of ordinary citizens and the financial interests of businesses. Pollution is a byproduct of industrial technologies and global trade. Handmade paper and vegetable dyes cause no pollution; indigenous leather treatment is also very prudent and water conserving; fresh vegetables and fruits do not require water, except for cultivation.

By contrast, modern industrial papermaking and leather processing create massive pollution. Pulp uses 60,000 to 190,000 gallons of water per ton of paper or rayon. Bleaching uses 48,000 to 72,000 gallons of water per ton of cotton. Packaging green beans and peaches for long-distance trade can use up to 17,000 and 4,800 gallons per ton, respectively.22

The overuse and pollution of scarce water resources is not restricted to old industrial technologies; it is a hidden component of the new computer technologies. A study by South West Network for Environmental and Economic Justice and the Campaign for Responsible Technology reveals that the process of chip manufacturing requires excessive amounts of water.

On average, processing a single six-inch silicon wafer uses 2,275 gallons of deionized water, 3,200 cubic feet of bulk gases, 22 cubic feet of hazardous gases, 20 pounds of chemicals, and 285 kilowatts hours of electrical power.23 In other words,

if an average plant processes 2,000 wafers per week (the new state-of-the-art Intel facility in Rio Rancho, New Mexico, for example, can produce 5,000 wafers per week) it would need 4,550,000 gallons of water per week and 236,600,000 gallons per year for wafer production alone.24

The study finds that out of the 29 Superfund sites in Santa Clara County, California, 20 were created by the computer industry.

The Principles of Water Democracy

At the core of the market solution to pollution is the assumption that water exists in unlimited supply. The idea that markets can mitigate pollution by facilitating increased allocation fails to recognize that water diversion to one area comes at the cost of water scarcity elsewhere.

In contrast to the corporate theorists who promote market solutions to pollution, grassroots organizations call for political and ecological solutions. Communities fighting high-tech industrial pollution have proposed the Community Environmental Bill of Rights, which includes rights to clean industry, to safety from harmful exposure, to prevention, to knowledge, to participation, to protection and enforcement, to compensation, and to cleanup.25 All of these rights are basic elements of a water democracy in which the right to clean water is protected for all citizens. Markets can guarantee none of these rights.

There are nine principles underpinning water democracy:

1. Water is nature’s gift

We receive water freely from nature. We owe it to nature to use this gift in accordance with our sustenance needs, to keep it clean and in adequate quantity. Diversions that create arid or waterlogged regions violate the principles of ecological democracy.

2. Water is essential to life

Water is the source of life for all species. All species and ecosystems have a right to their share of water on the planet.

3. Life is interconnected through water

Water connects all beings and all parts of the planet through the water cycle. We all have a duty to ensure that our actions do not cause harm to other species and other people.

4. Water must be free for sustenance needs

Since nature gives water to us free of cost, buying and selling it for profit violates our inherent right to nature’s gift and denies the poor of their human rights.

5. Water is limited and can be exhausted

Water is limited and exhaustible if used nonsustainably. Nonsustainable use includes extracting more water from ecosystems than nature can recharge (ecological nonsustainability) and consuming more than one’s legitimate share, given the rights of others to a fair share (social nonsustainability).

6. Water must be conserved

Everyone has a duty to conserve water and use water sustainably, within ecological and just limits.

7. Water is a commons

Water is not a human invention. It cannot be bound and has no boundaries. It is by nature a commons. It cannot be owned as private property and sold as a commodity.

8. No one holds a right to destroy

No one has a right to overuse, abuse, waste, or pollute water systems. Tradable pollution permits violate the principle of sustainable and just use.

9. Water cannot be substituted

Water is intrinsically different from other resources and products. It cannot be treated as a commodity.

1. Institutes of Justinian 2.1.1

2. William Blacks tone, quoted in Walter Prescott Webb, The Great Plains (New York: Grosset and Dunlop, 1931).

3. Chattarpati Singh, “Water and Law” (n.d.).

4. Devon Pena, ed., Chicano Culture, Ecology and Politics (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1998), p. 235.

5. Donald Worster, Rivers of Empire: Water; Aridity, and the Growth of the American West (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985), p. 88.

6. Ibid., p.89

7. Ibid., p.104.

8. Ibid., p.90.

9. Terry Anderson and Pamela Snyder, Water Markets: Priming the Invisible Pump (Washington, DC: Cato Institute, 1997), p. 75.

10. Jatinder Bajaj, “Green Revolution: A Historical Perspective” (paper presented at ‘CAP/TWN Seminar on “Crisis of Modern Science,” Penang, November 1986), p. 4.

11. Nirmal Sengupta, Managing Common Property: Irrigation in India and The Philippines (New Delhi: Sage, 1991), p. 30.

12. N. S. Jodha, “Common Property Resources’and Rural Poor,” Economic and Political Weekly 21, No. 7 (July 5, 1986).

13. John Lock, Second Treatise on Civil Government, (Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1986), p. 20.

14. Garrett Hardin, “Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162 (1968): pp. 1243-1248.

15. Devon Peña, ed., Chicano Culture, Ecology and Politics (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1998), p. 235.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid., p. 242.

18. Devon Peña, “A Gold Mine, an Orchard, and an Eleventh Commandment,” in Pena ed., Chicano Culture, Ecology and Politics (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1998), pp. 250-251.

19. Anupam Mishra, “The Radiant Raindrops of Rajasthan,” translated by Maya Jani (New Delhi: Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology, 2001).

20. Chattarpati Singh, “Water and Law.”

21. Terry Anderson and Pamela Snyder, Water Markets, p. 149.

22. Peter Rogers, Americas Water: Federal Roles and Responsibilities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993).

23. South West Network for Environmental and Economic Justice and Campaign for Responsible Technology, Sacred Waters (1997), pp. 19-20.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid., pp. 133-134.