9

“TOUCHING GREATNESS: THE CENTRAL MIDWEST BARRY MANILOW FAN CLUB” 1 (1991)

Thomas C. O’Guinn

MODERN CELEBRITY

Christianity will go. We’re more popular than Jesus now.

—JOHN LENNON (1966)

It seemed to me then, as it does now, that one of the undeniable hallmarks of American consumer culture is a fascination with celebrity. Each week approximately 3.3 million Americans read People (Simmons Market Research Bureau 1990). Anyone who reads newspapers or magazines or watches television, will have no doubt noted that a great deal of air time and print space is devoted to covering celebrities. This interest and attention is not restricted to a certain social class; all have their celebrities, although each class tends to think the other misguided or too unsophisticated to appreciate the truly great. Some read of their admired ones in tabloids, others in the chic magazine of the “intelligentsia.”

At the center of all this attention is a great deal of consumption. At least one million Americans belong to a fan club (Dornay 1989). Approximately five million tourists have visited Graceland since being opened to the public in 1982, 60,000 alone during “Elvis Week”

2 marking the tenth anniversary of Mr. Presley’s death. Tourists throng to celebrity graveyards in Los Angeles; the most famous of them, Forest Lawn is often referred to as the Disneyland of cemeteries. Others take drive-by bus tours of the homes of the stars. “Meet-a-Celebrity” tie-ins and other promotions are becoming routine. The production and marketing of celebrity could reasonably be called one of America’s largest industries.

Yet, the question of why remains. Why do we devote so much attention to celebrities? Why do “we live in a society bound together by the talk of fame” (Braudy 1986, p. vii)? Why do celebrities matter so much to us; and from the perspective of consumer research, why do they sit at the center of so much buying and consuming?

Apparently no one is really even sure how long the celebrity has been with us.

3 Braudy (1986) traces the notion back to Homeric legends and early concepts of gods. Another frequently applied model is the traditional hero within the context of myth, probably best described by Campbell in his classic,

Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949). Heros and their associated myths help us make sense of our lives, better understand our connections to each other and our culture. There is also something special about heros in a techno-science culture where the concept of god is so fundamentally threatened. The need for magic may be at its greatest in such a world. This is the modern “crisis of heroism” put forth by Becker (1973) in

The Denial of Death. When heros and gods are reasoned away, a vacuum of anxiety remains. Amplifying Becker (1973), Rollin (1983; 38) says:

the therapy for the Age of Anxiety is apotheosis, the transformation of a human being into a heavenly being, a star, a hero, a god, a symbol of human potential realized.

Others (i.e., Klapp 1969; Lowenthal 1961) have argued that celebrities exist to give the individual identity in a modern mass culture. In this notion’s most recent incarnation, Reeves (1988) presents an intriguing thesis on stardom, casting it as a cultural agent of personality development and social identification. Even though his specific focus is television stardom, the idea that stardom is a “cultural ritual of typification and individuation” extends well beyond that particular medium. Drawing on the work of Carey (1975), Geertz (1973), Bakhtin (1981) and Dyer (1979), Reeves (p. 150) argues that television stars help the individual connect who he or she is with “appropriate modes of being in American culture,” or cultural “types,” while at the same time providing just enough quirks against type to believe that we, like the stars, are actually unique individuals.

One of the more influential thoughts in conceptualizations of celebrity is Max Weber’s (1968, v. 1. 241) concept of “charisma”:

to be endowed with powers and properties which are supernatural and superhuman, or at least exceptional even where accessible to others; or again as sent by God, or as if adorned with exemplary value and thus worthy to be a leader.

However, as impactful as this concept has been, few suggest a wholesale application of the “charismatic leader” (Weber 1968) concept to modern celebrity. The reasons are generally because the sociologist-cum-economist Weber’s formulation requires a purposeful leader, a stable social system, and a clearly discernable power relationship. Two of these almost never exist in the case of modern celebrity, and the other, a stable social system, is a matter of some debate and interpretation (see Dyer 1979 and Alberoni 1972). Edward Shils (1965) also takes Weber to task for his narrow institutional conceptualization of charisma, and offers a much broader view of the concept. Still, it is Italian sociologist Francesco Alberoni who proposes a purely apolitical and modern model of celebrity.

Alberoni (1972) argues that the modern “star” does not and cannot possess generalized “charisma” in the true Weberian sense. Modern societies are too specialized to allow stars the kind of institutionalized power that Weber’s charismatic leader demands. However, he does believe that they are perceived by their adoring masses as possessing some demi-divine characteristics that make them “elite” rather than charismatic. They are seen as spiritually special, but lacking any type of political power. Alberoni thus terms stars the “powerless elite.”

In fact, it could be that ritual is the central element in the Touching Greatness phenomenon. Rituals linger well beyond their substance. They can still be comforting even though their spiritual basis is long gone. Prayers said to a god not truly believed in may still benefit the supplicant. So too may be visiting the place of rituals, the church—even though the gods have gone away. Touching greatness may be a form that is substantially vestigial. The practice satisfies even though it is absent of much contemporary meaning. This could help explain why we seem to have such a need for celebrities which Boorstin (1962) saw as nothing more than “human pseudo-events,” and people famous for being famous.

TOUCHING GREATNESS

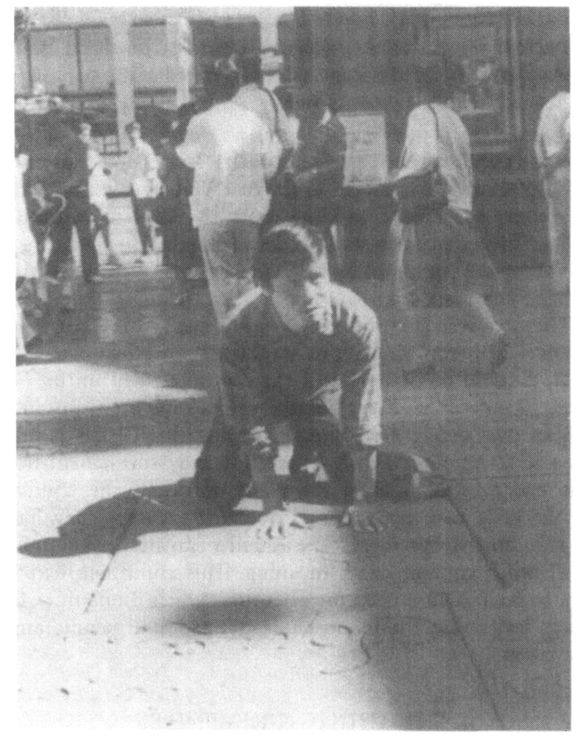

The Touching Greatness project began at Mann’s Theater in Los Angeles. We (Belk, O‘Guinn, Sherry, Wallendorf) interviewed several people engaged in what seemed a particularly interesting form of consumer behavior. People spent from a few minutes to a few hours milling about looking at the hand and foot prints of movie stars. Some, such as the individual in

Figure 10, chose to bend down, often while being photographed by a family member or friend, and place their own hands or feet in the impressions left by the stars. Some bought Hollywood and celebrity related souvenirs, signed up for tours of the stars’ homes, and otherwise participated in the celebrity centered consumption experience. Interviews then and during a return trip by Belk and O’Guinn two years later revealed that to many it was merely something to do, just situationally normative behavior and curiosity. For others, it meant something more: a chance to remember and pay homage, to explain to their children who these men and women were and why they were important in their lives. Touching Greatness is more about the latter, or “true fans,” but is not wholly without connection to the former appreciative masses. It remains an interesting and legitimate question why behaviors such as those observed at Mann’s Theater are norms within our culture, and why such popular shrines exist at all.

The Central Midwest Barry Manilow Fan Club (CMBMFC) data are offered here as a case within the larger phenomenon and not as complete ethnography. These data will not allow the reader the depth necessary to fully appreciate the unique character of this particular club, for they were not collected for that purpose. Rather, they illustrate some of the themes observed across locales and fans.

CENTRAL MIDWEST BARRY MANILOW FAN CLUB

Barry Manilow

4 is a celebrity. I talked to some of his fans. At the time the data were collected several themes had emerged from work at other Touching Greatness sites. The data collected here and at subsequent locales were used to expand upon what had already been learned, and to test the evolving model with new data. What follows are some of these findings, along with illustrative text and photos.

The findings being reported here are based on thirty hours of interviews with eighteen members of the CMBMFC. The informants were all women. Most were in their mid-thirties to mid-forties. Socioeconomic-status varied, but was typically observed to be lower middle class. We saw no men, but were told that there were a few male members.

5 Interviews were conducted in three places: a small restaurant, the home of the CMBMFC president, Bobbie, six hours prior to a Barry Manilow concert, and in a backstage press area secured exclusively for our use before and after the show. Besides the author, five graduate assistants, three men and two women, participated in the fieldwork.

THEMATIC FINDINGS

The Touching Greatness phenomenon has a broad cultural foundation. Apart from aspects of religion, I observed evidence of the fan club as surrogate family, and what could reasonably be viewed as a socialization outcome of life in a society in which the average family watches over seven hours of television a day (Condry 1989). Yet, the single best organizing structure is the first of these: religion. Perhaps it is because it is such a primal structure. Humans have been using it as a conceptual framework for explaining their existence, plight, and just about everything else for centuries. It is a very convenient and familiar source for interpretation and attribution. Religion has so many points of contact with so many aspects of believers’ lives, that it is sometimes hard to see where it starts and stops. With this caveat in mind, a discussion of some of the uncovered themes follows. They are not exclusively religious, but are not inconsistent with a religious interpretation.

BARRY Is EVERYTHING

“He’s a husband, he’s a lover, he’s a friend, he’s everything.”

Barry Manilow pervades the lives of the members of the CMBMFC. In a very real sense, he is “everything.” Evidence of this comes in several forms. First, there is the more concrete, such as the expenditure of time and money. It is not uncommon for the members to attend five shows a year, often traveling considerable distances. There is also the purchase and creation of Barry Manilow paraphernalia. These include hundreds of photographs, extensive album and video collections, clipping files and other memorabilia. Large phone bills from calling other Barry Manilow members are common. Vacations are scheduled around tour dates. Life revolves around Barry. In terms of time and money, Barry is a primary beneficiary of these typically scarce resources.

Invoking Barry’s name and spirit also makes important rituals and life events even more special, or sacred (Belk, Sherry and Wallendorf 1991). A particularly palpable example was when Bobbie and her husband were married. The couple had a number of Barry’s songs played at the wedding, and the sheet music to a particular song, “Who Needs to Dream,” was superimposed over the couple’s wedding photograph (

Figure 11). Many religions place a god or other important personage (i.e., saint, martyr, prophet, etc.) at the center of celebrations and rituals marking important life events, such as weddings, which thereby come to be regarded as sacred institutions.

Barry’s pervasiveness in the lives of the CMBMFC members was also apparent in that they often referred to him in terms of a significant other, most typically as lover, husband or friend. This love was, however, rarely sexual. It was rather more spiritual love, though often with an idealized romantic pallor. For example, one woman who describes herself as a very faithful wife, says she takes off her wedding ring on only one occasion: to attend Barry Manilow concerts. She does this although she and Barry Manilow have no personal relationship in any traditional sense; yet, she sees important symbolism in the act. This is an important thing for her to do. It would, after all, be wrong to be married to two men at once. Extending the religious metaphor, some nuns wear wedding bands to symbolize their marriage to Christ.

Perhaps most significantly, informants explain that Barry is able to provide the emotional support and understanding they need like no one else in their lives. I was told that he “never lets them down.” CMBMFC members frequently describe him as “all” of these important roles or personages “rolled into one,” someone who can be all, provide all.

I believe in God, and I kind of think God sent Barry to help me. I think a lot of people feel that way, he’s got a special gift and he kind of reaches out to a lot of people.

Barry’s specialness occasionally borders on the miraculous. Bobbie tells of a time when a group of CMBMFC members were camping out for tickets in cold and wet weather. They had been out all night in rain and cold when sandwiches and coffee arrived “from nowhere.” Bobbie was amazed that what initially seemed like a meager amount of food had “fed everyone.” We also spoke to a woman who told us that Barry had “somehow” heard of her child who had cancer, picked him up in his limousine and visited with he and his mother at their home. On another occasion, the CMBMFC members were waiting for Barry’s plane to land. The weather was bad, but when Barry’s plane approached, the sky cleared and it was able to land. When he was safely inside the terminal, it started raining again.

BARRY’S WORK

Like most religions, this church has a mission; there is work to be done. Among the important duties are taking care of Barry, protecting him from bad fans, recruiting new followers, and always being there for him. These are all seen as important functions for members of the CMBMFC. Perhaps chief among them is the idea of providing emotional support to Barry and otherwise taking care of him. Sometimes, we think of gods taking care of their followers, and not vice versa. But in fact, in many religions that is precisely the purpose of human existence, to serve god. Christians, for example, are told that the path to heaven and happiness is through serving the Lord, doing His work. Sometimes “His work” is in the form of altruism, serving god by serving others. Such behavior is very consistent with that observed among CMBMFC members. They are quick to point out that Barry and his fans do a great deal of charity work.

It is here that the role of wife/mother becomes most intermingled with that of religious follower. The women of the CMBMFC seem to derive a very important benefit from taking care of Barry, giving of themselves. They believe he needs and appreciates this effort, his appreciation being very significant. In preparation for the show we attended, four different fan clubs competed to decorate Barry’s dressing room. The members of the CMBMFC explained that decorations let Barry know they care, and are “there for him.” They also wanted to make him as “comfortable as possible.”

Some members have very personal ideas and aspirations about serving Barry. The president of the CMBMFC, herself a professional secretary, says that if she could be anything at all in relation to Barry she would be his secretary:

I would like to just spend a day following him around with my little clipboard or whatever saying “you’ve gotta be here, you’ve gotta be here, you’ve got a meeting with so and so” and just do that for a day. That’s all I want.

Serving Barry even extends to cleaning for Barry. After one show a group of CMBMFC members waited for Barry to leave his dressing room. When he did, he looked at the arena and commented on how dirty it was. They then explained that this was true except for the rows in which they had sat. Those were clean:

He [Barry] said something like “what went on here today, looks like they had a circus, popcorn all over the floor” and I said “yes, but the first three rows are clean.” He turns to Mark and he says “you’re right, where they sat, those rows are clean.”

Churches must be kept clean. True believers respect the sacred space, whereas infidels defile it. Members of the CMBMFC are true believers.

Still, after telling the researchers so much about what they did for Barry, the opposite question was posed.

Researcher: And what does he give you?

Bobbie: Just knowing that he’s there and he cares, you know, like I told her (my friend) tonight going to the mall. I said “this man, the fact that he does realize what he puts us through.”

Appreciation, particularly from a male, seemed very important. Further, it doesn’t seem entirely coincidental that when asked to explain what makes Barry so good, informants very frequently mention that Barry is very good to his mother. Here is where the devoted religious follower and the role of the long suffering and nurturing woman intertwine. The fan’s object of devotion is a person to whom they ascribe the attributes of specialness, extending to religious proportions. They serve him, and are happy in their work. It is not, however, insignificant that this minor deity or religiously imbued person is male. It is also important that this paradoxical relationship to suffering and pleasure seems so central to the gratifications derived by these women. It is also entirely consistent with the happy sufferer paradox of many religious experiences.

SUFFERING FOR BARRY

“Our day will come.”

“Mostly they just sit and shake their heads at us.”

“I mean he cares for us too. In fact, he even told us . . . ; “I know you put up with a lot of grief and I’ve heard every name in the book just like you’ve heard every name in the book and you put up with a lot,” and he said “I want you to know I’m here,” and he did everything he could do to make sure it doesn’t happen but it’s always gonna happen and he feels terrible about it because we’re considered his ladies and he takes care of us . . .”

“He realizes what he puts you through.”

The members of the CMBMFC speak of the ridicule and oppression they must face for their beliefs. Their families, particularly their husbands, do not understand their devotion and love for Barry. People make fun of them. Yet, it is suffering not entirely without reward; there is a bit of martyrdom related satisfaction apparent in some informants.

SHRINES AND RELICS

Many fans have collections of Barry Manilow things. Some have special “Barry Rooms” set aside for the display of their collections. Others have only parts of rooms, some just closets. Almost all attribute lack of room for Barry to unsympathetic husbands. Consistent with other research on collections (Belk, Wallendorf and Sherry 1989), the job is never done, collections are never complete. There’s always more Barry stuff. Few would sell even a single piece of their collections, and they rank their contents as their most prized and meaningful possessions.

I’d kill just about anybody if they just go in the room and try to walk out of the room with a poster, a record, just a clipping out of a newspaper, scraps of tickets, you name it. A lot of us have rooms devoted to just that, in fact, few of us have understanding husbands. I’m about one of the only ones in the entire Central Midwest Club that lets me do all of that.

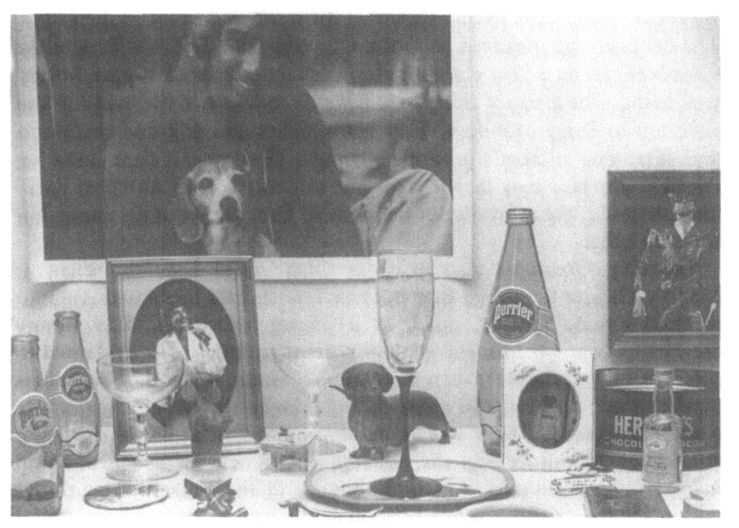

Bobbie’s room is featured in two photographs (

Figures 12 and

13). She devotes one of the bedrooms of her house to this pursuit. The room is covered in posters, photographs, clippings, letters, autographs, etc. These things have a great deal of meaning for Bobbie. These are special because they involve Barry, and form an important emotional conduit to networks of friends, memories and an important sense of self.

The highest status things in the collections are the things actually touched by Barry. This somehow proves that Barry exists for them, through this person-to-object-to-person connection (McCracken 1986). It is physical evidence of a personal relationship. A good example was a Perrier bottle from which Barry had drunk. This bottle occupies a prominent place on Bobbie’s shelf. The smaller bottles belong to members of Barry’s entourage.

This collecting of things actually touched by the admired one is a particularly interesting aspect of the Touching Greatness phenomenon. It was observed consistently across venues and celebrities, and is very consistent with a liturgical interpretation, going as far as the levels of sacredness assigned to religious relics (Geary 1986) depending on how “near” they were once to the sacred being. It also draws us back full circle to the behavior observed at Mann’s Theater, of wanting to actu-ally touch the concrete images left by the stars. It wouldn’t be the same consumption experience if Plexiglas covered the concrete impressions.

Yet another important distinction concerning collections should be noted. Apparently, “real fans” don’t sell Barry things at a profit. This helps distinguish the infidel from the true believer. One of the most common behaviors at a Manilow concert is taking photographs of Barry, lots of them. Bobbie, for example, will take four to eight 24 exposure rolls per show, and see several shows per year. The photos taken of Barry are sold at cost or traded with other fans, but “it would be wrong” to sell them.

The only thing I ever charge is if they want copies and they send me just for the print. Barry doesn’t like when you make a profit.

This is very reminiscent of the parable of Christ driving the merchants from the temple. Apparently, putting a price on something that is seen as without price would seem profane or vulgar and would move something sacred into the secular domain, and thus cheapen it (Belk, Sherry and Wallendorf 1989).

FELLOWSHIP

Fellowship seemed to be the greatest of all the benefits of CMBMFC membership. Respondents talked at length of how much getting together with one another meant to them. Many said that relationships started via membership have become some of the most important in their lives. The behavior we observed supports this assertion. The members of the CMBMFC seemed very close and legitimately interested in each others’ well-being. The greatest thing they have in common is the love for and devotion to Barry Manilow. They get together and talk and reminisce, and share one another’s joys and sorrows. There was a clear bond between them. This may be the strongest evidence for a Church of Barry interpretation, the centrality of fellowship. They gather in his name, but for each other.

Touching Greatness also provides other social benefits. When at Mann’s Theater it seemed that the concrete shrines facilitated communication among visitors, much of it inter-generational. Why Jimmy Stewart or Marilyn Monroe were important to father was explained to son. For others, the stars were known-in-common referents. Their films marked time, set events in context, and seemed to provide meaning in a non-trivial way. There was something important underneath this, a connection to culture and the individual within it, with consumption being an important part of the link. Buying, giving and collecting things within the touching greatness phenomenological frame is common and important to those involved. It concertizes the experiences and facilitates social interaction.

DISCUSSION

Religion is one of the oldest of culture’s creations. Yet, “dead are all the gods” (Nietzsche 1893). Science and the ascendancy of the individual has either killed them or made of them vestigial forms which only vaguely resemble their ancestors. As the traditional social structures are challenged, evolve or succumb, contemporary cultures recast old into new. What were god-centered religions may be easily converted into social structures for celebrity worship. Even though few if any CMBMFC members actually believe Barry Manilow to be a god, they do attribute the qualities of the religiously blessed to him. They certainly believe him to be closer to god than they are. Clouds part when his plane lands; he supplies food in mysterious ways; and he possesses a special sense of knowing about his followers’ lives that is clearly beyond mortal. This is a religious system. By any standards Barry Manilow is worshipped by his fans. He is someone more than a priest and someone less than the son of God in a traditional Protestant Christian model. In contrast, data from Elvis Presley fan clubs show his fans as seeing him closer to truly divine; whereas data from Johnny Cash fan clubs show a very fallible mortal, but still spiritually special.

The Touching Greatness data provide support for the thesis that celebrities perform some of the functions of gods, or god-sent beings. Yet, also clear is support for the idea that the fan club serves some of the social function churches once did. There, people who share a deep devotion or admiration for a special individual, meet and form important bonds, and fulfill important social needs once facilitated by the church. Maybe these fan clubs have taken on such a liturgical feel because the religious form was simply the most familiar, the most easily borrowed and transformed. The church is replaced in form, if not substance because it has the best, most familiar and most comfortable bundle of social uses, gratifications and shared meanings. We may miss God less than we miss each other.

While it is sometimes argued that extreme or marginal forms of behavior such as fanaticism are both qualitatively and quantitatively distinct from their more “normal” expression, it seems difficult to explain one without the other. The very fact that Graceland and Mann’s Theater exist and flourish means something apart from fanaticism. Likewise, the significance of the Touching Greatness phenomenon exists beyond the dispositional properties of individuals. It says something about the stage of a society’s development (Alberoni 1972), our collective needs, motivations and values, and how these are expressed through consumption.

There’s a great deal of consumption in the Touching Greatness phenomenon. Yet as a field we have chosen not to give this and other aspects of popular culture much attention. Perhaps that is precisely the reason; it is too popular. Academics can be the worst snobs of all in their refusal to consider the popular (see Lewis 1988; Bellah et al. 1985). This seems odd, since by definition, it is where so much of life occurs.

ENDNOTES

1 The author would like to thank Mark Michicich, L. J. Shrum, Lisa Kay Sla-bon, Lisa Braddock, Ian Malbon, and Connie O’Guinn, who participated in this research. Further thanks go to Bill Wallendorf, Molly Ziske, Kim Rot-zoll, Russell Belk, and the staff of the Overland Cafe, Los Angeles.

2 An Elvis week consists of nine days.

3 While there are many reasonable definitions of celebrity, and related terms such as “fame,” “star,” and “renown,” I choose to simply define a celebrity as one who is known by many, but knows far fewer, and the object of considerable attention.

4 Barry Manilow is a popular contemporary song stylist.

5 Most males mentioned were Barry impersonators.

REFERENCES

Alberoni, Francesco (1972). “The Powerless Elite: Theory and Sociological Research on the Phenomenon of Stars,” in D. McQuail (ed.) Sociology of Mass Communication, Baltimore: Penguin, 75-98.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981), The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, M. Holquist (ed.), C. Emerson and M. Holquist (trans.), Austin: University of Texas Press.

Becker, Ernest (1973), The Denial of Death, New York: The Free Press.

Belk, Russell W., Melanie Wallendorf and John F. Sherry, Jr. (1989). “The Sacred and the Profane in Consumer Behavior: Theodicy on the Odyssey,” Journal of Consumer Research, (16:1), 1-38.

Belk, Russell W., Melanie Wallendorf, John Sherry, Jr. and Morris B. Hol-brook (1991), “Collecting in a Consumer Culture,” in Russell W. Belk (ed.), Highways and Buyways: Naturalistic Research from the Consumer Behavior Odyssey, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Bellah, Robert N., Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swindle, and Steven M. Tipton (1985), Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Boorstin, Daniel (1962), The Image: Or What Happened to the American Dream, New York: Atheneum.

Braudy, Leo (1986), The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History, New York: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, Joseph (1949), The Hero With a Thousand Faces, New York: Pantheon.

Carey, James (1975), “A Cultural Approach to Communication,” Communication, 2, 1—22.

Condry, John (1989), The Psychology of Television, Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Darnay, Brigitte T. (ed.) (1989), Encyclopedia of Associations 1990, vl. pt. 2, sections 7-18, Detroit: Gale Research.

Dyer, R. (1979), Stars, London: British Film Institute.

Geertz, Clifford (1973), The Interpretation of Cultures, New York: Basic Books.

Geary, Patrick (1986), “Sacred Commodities: The Circulation of Medieval Relics,” in Arjun Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press, 169—191.

Klapp, Orrin E. (1969), Collective Search for Identity, New York: Holt, Rine-hart and Winston.

Lennon, John (1966), New York Times, “Comment on Jesus Spurs a Radio Ban,” Aug 5, 1966, page 20, column 3.

Lewis, George H. (1988), “Dramatic Conversations: The Relationship Between Sociology and Popular Culture,” in Ray B. Browne and Marshall W. Fishwick (eds.), Symbiosis: Popular Culture and Other Fields, Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 70-84.

Lincoln, Yvonna S. and Egon G. Guba (1985), Naturalistic Inquiry, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lowenthal, Lowel (1961), “The Triumph of Mass Idols,” in Lowel Lowenthal (ed.), Literature, Popular Culture and Society, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp. 109-140.

McCracken Grant (1986), “Culture and Consumption: A Theoretical Account of the Structure and Movement of the Cultural Meaning of Consumer Goods,” Journal of Consumer Research, 13:1 (June), 71-84.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (1893), Also Sprach Zarathustra, Leipzig: C. G. Nau-mann.

Reeves, Jimmy L. (1988), “Television Stardom: A Ritual of Social Typification,” in James W. Carey (ed.), Media, Myths and Narratives: Television and the Press, Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 146-160.

Rollin, Roger R. (1983), “The Lone Ranger and Lenny Skutnik: The Hero as Popular Culture,” in Ray B. Browne and Marshall W. Fishwick (eds.), The Hero in Transition, Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 14-45.

Shills, Edward (1965), “Charisma, Order and Status,” American Sociological Review, 199—233.

Simmons Market Research Bureau (1990), “Study of Media and Markets,” New York: Simmons Media Research Bureau.

Weber, Max (1968), Economy and Society, v-13, New York: Bedminster.