Don’t therefore be surprised, Socrates, if on many matters concerning the gods and the whole world of change we are unable in every respect and on every occasion to render a consistent and accurate account. You must be satisfied if our account is as likely as any, remembering that both I and you who are sitting in judgment on it are merely human, and should not look for anything more than a likely story in such matters.

PLATO, TIMAEUS

A Likely Story

In the beginning was chaos. This is as likely a story as any: cosmos from chaos, order from disorder, the whole world assembled from some formless flux. But what kind of a starting point is chaos, when chaos confounds all points? How do boundaries emerge from the boundless, things from the no-thing, information from the noise?

The most ancient of Greeks addressed this problem by positing an organizing force internal to the precosmic flux. In Hesiod’s Theogony, for example, a primordial Chaos gives birth spontaneously to the earth, who in turn gives birth to heaven, through whom she conceives the ocean, time, and countless violent gods.1 As the early Ionian philosophers sought to replace such mythology with a purely “rational” cosmogony, they transformed Chaos from a primordial goddess into one of the natural elements, which produced all things and would reclaim them in time.2 This primary substance was water for Thales,3 air for Anaximenes,4 fire for Heraclitus,5 and a pre-elemental “boundless” for Anaximander.6 For Empedocles, the primary substance was all four elements (earth, air, fire, and water), which are separate from one another during a periodic stage of cosmic “strife” and indistinguishable from one another during the opposing periodic stage of “love.”7 The cosmos we inhabit must exist somewhere between these two stages; for Empedocles, both the total separation and the total union of the elements amount to chaos, which means that order itself is a fragile mixture of sameness and difference.

Then, with the rise of Atomism in the late fifth century B.C.E., Chaos was shattered into countless invisible bodies moving aimlessly in a void. Each atom (from the Greek atomos [uncuttable]) was said to collide haphazardly with other atoms, their collisions forming an infinite number of worlds in random motion. As one world crashed into another, both would unravel again into a primal swarm of atoms, and the whole process would repeat.8 A century later, the Stoic school would posit a “Phoenix” universe that was born, destroyed, and reborn in fire.9 Whether mythos or logos, however, these are all similar tales: out of the primordial mess comes the whole world, and back into it the world will one day be absorbed. Water to water, atoms to atoms, chaos to chaos.

Hesiod, the Ionians, and the Atomists provide most of the cosmogonies that would have been familiar to Timaeus, the astronomer and primary speaker in the Platonic dialogue that bears his name.10 Like his philosophic predecessors, Timaeus describes the birth of the cosmos as an ordering of disorder, telling us that in the beginning the universe was a mess of forces in unruly motion.11 The difference is that Timaeus does not attribute the ordering of this mess to an internal principle; rather, he explains it as the work of a god (demiourgos). For the first time in Greek philosophy, cosmogony is narrated as creation:12 far from emerging out of the primordial element (or being it, as the Stoics will argue), the god of the Timaeus is external to the unformed world, “finding the visible universe in a state not of rest but of inharmonious and disorderly motion” (30a).13 Immediately upon “finding” it thus—as if stumbling on it one day, shocked to come across anything so material, so unintelligible, so out of control—the god “reduces” the world “to order [taxis] from disorder,” using as his model the idea of a “perfect living creature”—perfect because it “comprises all intelligible beings” (30a, 31b). The perfect living creature, in other words, is something like the Form of Forms—the Idea that contains all other ideas within it. In this light, the demiurge looks remarkably like the Republic’s philosopher-king, who puts the city in order by fixing his eyes on the Good.14 With his hands in the chaos and his gaze on the Forms, the god of the Timaeus shapes the material world into a “visible, tangible, corporeal” image of the ideal and eternal (28c).

Against the (unnamed) Atomists and their randomly colliding worlds, Timaeus argues that the intelligently designed cosmos cannot be one of many kosmoi, let alone an infinite number of them. Rather, it must be singular—as unique as the Form of the “perfect living creature” it mirrors:

Are we right then to speak of one universe [ouranos], or would it be more correct to speak of a plurality or infinity? ONE is right, if it was manufactured according to its pattern; for that which comprises all intelligible beings cannot have a double…. In order therefore that our universe should resemble the perfect living creature in being unique, the maker did not make two universes or an infinite number, but our universe was and is and will continue to be his only creation. (31a–b)

The argument here is that the universe must be singular in order to resemble its model most perfectly. The model itself must be singular because it must include “all intelligible beings” (if there were more than one such model, then they would simply be copies of the genuine Form of the perfect living creature). In short, because singularity is more perfect than plurality, there can only be one model, and because there is only one model, there is only one world.

Just as the Platonic cosmos must be singular, it must also be indestructible. Timaeus’s reasoning is as follows: a body can be destroyed only by something inside it or something outside it. If something inside the world were to destroy it, it would do so either by violence or by gradual decay. But violence will never destroy this cosmos because, as we experience all the time, the elements exist in perfect harmony. And decay will never undo it because the death of any part of the cosmos—whether animal or vegetable—nourishes the whole (32b–33b). Even the periodic destruction of whole cities by flood and fire does not damage the world as a whole; rather, new civilizations will arise in their place (39d). Internally, then, the world is “ageless and free from disease” (33a). And externally, Timaeus assures us, the world is also free from danger because the god in his wisdom “used up the whole of each of [the] four elements” in creating it (29e, 32c). In other words (and, again, implicitly against the Atomists), there is nothing outside the world—neither other worlds nor extraneous particles that might vex it from without. The only power who might undo the cosmos would be the god himself, but his untrammeled goodness prevents his committing any such crime. As the demiurge tells the lesser gods he goes on to create, “Anything bonded together can of course be dissolved, though only an evil will would consent to dissolve anything whose composition and state were good. Therefore, since you have been created, you are not entirely immortal and indissoluble, but you will never be dissolved nor taste death, as you will find my will a stronger and more sovereign bond than those with which you were bound at your birth” (41a–b, emphasis added).15

Thanks to its benevolent sovereign, the world once delivered from chaos will remain perfectly ordered forever. Made in the image of the eternal and secured by divine will, the cosmos is unique and indestructible: a “single, complete whole” (33a, emphasis added).

Mixing the Multiple

Considered in this manner, the Timaeus seems to install cosmologically what eventually becomes the usual Western philosophical privileges: order over chaos, stasis over change, the intelligible over the sensible, and the singular over the plural. The model is one, so the world is one, and its order endures forever. As the story goes on, however, we find that this reading both does and does not hold. A strange dance between the one and the many begins the moment Timaeus, having established the singularity and indestructibility of the cosmos, goes on to explain how it was so made.

First, Timaeus details the god’s meticulous formation of the world’s “body” as a proportional balance of water and air, fire and earth (32b). Then he moves on to the world’s “soul,” telling his interlocutors that “god created the soul before the body … gave it precedence both in time and value, and made it the dominating and controlling partner” (43c, emphasis added). With this description, the reader stumbles: If the god created the soul before the body, then why did Timaeus tell the story the other way around? Why would he begin with the body if the god began with the soul? In his authoritative commentary on the Timaeus, classicist Francis M. Cornford skips quickly over this conundrum, saying that Timaeus starts his own story with the body “for convenience.”16 But why would it be more convenient to begin with the body, only to have to explain that it does not come first? What does it mean for the story to grant primacy to the body when the cosmogony grants primacy to the soul—especially considering Timaeus’s own recognition that cosmogony can only be a “likely story” (eikota mythos, 29c–d) to begin with?17 Is Timaeus telling the story badly?18 Is he reversing his own privileging of the soul over the body—whether playfully or unknowingly? Or is he simply demonstrating the difficulty of getting a solid beginning out of chaos?

Whatever the reason, Timaeus continues the story unself-consciously. The demiurge made the soul first so that, just as reason rules the passions and the guardians rule the merchants, the world’s soul might rule the body it precedes. Of what, then, is this regal soul made? Timaeus has just asserted its superiority over the body, so we might expect him to sustain this privilege and proclaim the soul to be immaterial. But, again, Timaeus throws us off course, saying that “he [the demiurge] composed [the world soul] in the following way…. From the indivisible, eternally unchanging Existence and the divisible, changing Existence of the physical world he mixed [synekerasato] a third kind of Existence intermediate between them” (35a). This very mixing, however, undermines Timaeus’s privilege of the soul over the body: How can the world’s soul be superior to the physical world if it is composed of the physical world? How can the soul have preceded the body “in time” if the soul is partially made of the body? And how can the world be singular, eternal, and indivisible if its soul is irreducibly mixed? Yet this seems to be the soul of the “one” world: a commingling of the indivisible and unchanging (the Forms), the divisible and changing (the physical world), and a third substance that is neither divisible nor indivisible—or perhaps a little bit of both. And the god has not finished yet. After mixing the (in)divisible and the (un)changing, “again with the Same and the Different he made, in the same way, compounds intermediate between their indivisible element and their physical and divisible element: and taking these three components he mixed them into a single unity” (35a). A very bizarre “single unity” indeed, this world soul is now a conglomeration of indivisible existence, divisible existence, indivisible sameness, divisible sameness, indivisible difference, divisible difference, neither divisible nor indivisible existence, neither divisible nor indivisible sameness, and neither divisible nor indivisible difference.

By means of this many-layered mixing, Timaeus explains, the demiurge was “forcing the Different, which was by nature allergic to mixture, into union with the Same, and mixing both with Existence” (35a). This, too, seems a strange thing to say: Surely sameness is more “allergic” to mixing than difference is? But if we grant Timaeus this odd proposition—that difference is in some way inimical to mixing—then we must conclude that the resulting mixture, by definition more plural than “the Same,” must also be different from “the Different.” The mixture is something like difference and nondifference or something different from difference and nondifference, and this mixture alone constitutes the “unity” of the world—this assemblage of parts its “indivisibility.” Perhaps predictably, this indivisibility is no sooner established than it is divided: after forcing the Same and the Different into “a single whole,” the god finishes the soul by making “appropriate subdivisions, each containing a mixture of Same and Different and Existence” (35a). And so the soul is a “union,” but it is a mixture. It is a “single whole,” but it has subdivisions, each of which is itself a mixture. This cosmic intermingling of the singular and the plural, different as it is from difference and irreducibly mixed in its sameness, is an instance of what I am proposing to call the multiple. Every time the Timaeus tries to assert the Oneness of the world, the text collides with something like multiplicity.

This peculiar tango of the one and the many finds inimitable elaboration in Michel Serres’s philosophical meditation on chaos. “For the Timaeus,” he muses, “the world is a harmony, the world is a mix, the world is unitary, formed, comparable, thinkable, but it is only mixed with mixtures, it is even a mix of mixes of mixes, but …” Serres imagines Plato as a jester-sailor, tacking in a different direction each time we think that we have cornered him: “The ruse goes on, and Plato pulls to the right to the one-ward, then he pulls to the left to the multiple-ward, then pulls to the right again … and so forth.” What this means for Serres is that Plato himself, unlike the reliably dualistic “Platonists,” does not exclude the different, the changing, and the material; rather, “he negotiates it,” sailing between the cosmic and the chaotic, the same and the other, the thinkable and the unthinkable.19 Although it is not clear whether such a “negotiation” is performed willingly or begrudgingly, one cannot help but agree that the will toward oneness in the Timaeus finds itself multiply interrupted. At every turn, we find the same shot through with the different, spirit with matter, existence with nonexistence, and all of them with a strange set of terms in between. Even in the hands of the most intelligent and benevolent god, cosmos emerges only by means of chaos, as a mixture of itself and what is not itself, of different and same, of “both/and” and “neither/nor”: what Serres calls “a pure multiplicity of ordered multiplicities and pure multiplicities.”20

From this mixture of mixtures, this multiplicity of multiplicities that composes the body and soul, Timaeus goes on to derive a number of the world’s components. Mininarratives explain the emergence of time, the sun and moon, the planets and their orbits, the gods, the human soul and body, light and vision, hearing and sound. And then, out of nowhere, Timaeus tells us that he is going to have to start again. Right after elaborating the gifts of harmony, speech, and rhythm, for no discernible reason at all, he interrupts his catalog to clarify that all the actions he has been describing are the work of divine intelligence (nous). But intelligence, he explains, is only half of the story. For although this god is perfectly rational, he is not free to dream up anything he likes. Rather, his intelligence must work together with “necessity” (ananke, 47e–48a). In other words, all the mixings we have encountered at the hands of intelligence must themselves be mixed with the possibilities and constraints of their materials—materials that come from the “inharmonious and disorderly” flux the demiurge initially “found.” Halfway into the cosmos, then, Timaeus heads back to chaos.

A Likelier Story

“So let us begin again,” Timaeus suggests (48e). Once again he throws the text’s will toward oneness into stunning disarray, for this story about The Beginning begins twice. Perhaps concerned that his audience might get up and leave, Timaeus assures us that this second beginning will be a better one than the first. This beginning will be “more rather than less likely” because it will call on a more original origin, allowing us to glimpse the precosmic chaos itself (48e, 52d–53b). But if this is the case, wonders the somewhat agitated reader, then why was this “more likely,” more primordial beginning not Timaeus’s first beginning? Why must the first beginning come second—the more original origin springing up in the middle of things? Why do we get a clear view of chaos only halfway through the formation of the cosmos?

We encountered a similar problem in Timaeus’s attempt to insist that the soul precedes the body that constitutes it. The difficulty in both cases is presumably that neither of these elements exists independently of the other, so, strictly speaking, there is no good place to start. One way through this morass would be to abandon the notion that the cosmos has a temporal beginning at all. This was the preferred interpretation of Xenocrates and the Academicians, who saw in the Timaeus an account of the eternal creation of the cosmos rendered in linear format.21 In fact, the only people who seem to have taken Timaeus’s “beginning” to be temporal (with a few exceptions)22 were those who sought to oppose it—the Peripatetics, Epicureans, and Stoics.23 In remarkably different ways that this book will address in time, each of these schools maintained against “Plato” that the cosmos had to be eternal in the direction of the past as well as in the direction of the future and so could not have had the temporal origin that “Plato” ascribed to it. But with most of these opponents long gone, Francis Cornford could state in the 1930s that “it is now generally agreed” that the Timaeus does not describe a beginning in time. Rather, he argued, the dialogue dramatizes the eternal creation of order out of disorder by means of Reason. As such, the very figure of chaos is “an abstraction—a picture of some part of the cosmos … with the works of Reason left out.”24

Along this interpretation, chaos would be something like the political philosopher’s “state of nature”—that is, a picture of the universe with the order subtracted from it. If this is the case, then the reason Timaeus cannot simply begin with chaos is that chaos already presupposes cosmos. In other words, “pure” chaos has never existed. At the same time, insofar as the term cosmos names the ordering of disorder, “pure” cosmos has never existed, either. In sum, the most we can say of cosmos and chaos is that each relies on the other. Chaos and cosmos are each other’s conditions of possibility as well as conditions of impossibility—that is to say, each is itself as never quite itself, or each is itself only in and through the other, which nevertheless undoes it.25 Although it is doubtful that Cornford would have extended his analysis quite this far, he did offer a fleeting suggestion “that chaos, if it never existed before cosmos, must stand for some element that is now and always present in the working of the universe.”26 As it turns out, this eternal “element” is none other than that “necessity” that prompts Timaeus to start his tale over in the first place (second place). So let us begin again.

Timaeus’s second beginning opens by introducing a new character: khôra, the eternal “receptacle” (hypodoche) in which the cosmos becomes itself.27 Admitting that all of this is “difficult and obscure,” Timaeus tries to explain that whereas his first story distinguished “two forms of reality” (the visible world and its invisible archetype), this second story will “add a third” (49a, 48e). Strictly speaking, however, he is not really adding a third; he is calling attention to that on which the first two relied. Unsurprisingly, this heretofore excluded condition of possibility, this container that is awfully hard to see from the visible world it bears, is figured in consistently feminine terms: khôra is named “the nurse of all becoming,” the spatial “mother” to the Formal “father” and the cosmic “son” (49a, 50d).28 But insofar as being belongs primarily to the Forms and only secondarily to the material realm, khôra herself “is” nothing. She receives but is not; she provides a place but remains “devoid of all character” (50c). In short, khôra functions as “a kind of neutral plastic material” onto which copies of the Forms are inscribed, taking the shape of whatever she receives and thus giving birth to the visible world (50c).

Having now established his full cast of characters, Timaeus can finally get to the very beginning and describe the state of things “before” creation—the primordial chaos. “My verdict,” he (re)begins, “can be stated as follows. There were, before the world came into existence, being, khôra, and becoming, three distinct realities” (52d, emphasis added).29 This distinctness, we come to learn, is precisely what makes the scene chaotic. Since nothing could “become” when becoming was disconnected from the khôra that brings being into being, “chaos” is nothing more and nothing less than the stuff of the cosmos in nonrelation.30

Timaeus illustrates this chaotic state by saying that the precosmic khôra contained no objects—only “traces” or “vestiges” (ichnê) of the four elements. Because these forces (dunameis) had no proper existence yet, they “swayed unevenly,” moving through khôra in a thoroughly disorderly fashion (52e). In keeping with his description of chaos as distinction, Timaeus explains that what made this movement “disordered” was its continual separation of forces. Rather than being drawn together, the precosmic forces were shaken “like the contents of a winnowing basket” into “different regions of space” (52e–53a).31 Similar forces clustered together, held apart from what was different, and as such they did not yet exist. This vision of chaos begins to make sense when one considers, for example, the processes of evaporation, rarefaction, and combustion: water, air, fire, and earth exist only insofar as they are transformed into one another.32 Clustering around nothing but themselves “before” the world was made, these “traces” could not become the full-fledged elements whose interrelations compose the cosmos. The work of creation is therefore to bring things into existence by relating them—by mixing together that which the chaos keeps separate.33

But here we should remember that, for Timaeus, this creative mixing is not simply made in accordance with the “invisible realm” of the Forms; rather, the invisible realm becomes part of the mix (“from the indivisible, eternally unchanging Existence and the divisible, changing Existence … he mixed a third” [35a]). If “chaos” names the unrelated plurality of the “three distinct realities” (being, khôra, and becoming), then “cosmos” names their interrelation—the mixture of mixtures that worlds the world. As such, it is only in relation that any of these “realities” can be said to be at all. At this point, the Platonist will surely object that the realm of the Forms exists independently of khôra and the visible world; by definition, the Forms are unconstituted by the material realm of change. And, indeed, the Forms may “exist” on their own in some timeless time and placeless place (How would we ever know?). But when it comes to the birth of the cosmos, the Forms can come into existence only by means of the matter with which they are mixed.34 In this sense, the Forms rely as fully upon khôra and her imprints as the imprints rely upon khôra and the Forms, and as khôra relies upon the Forms and imprints. Insofar as the world is composed only as the mixing of these “realities,” the invisible is not merely a “model,” the visible not merely a resource, and khôra not merely their receptacle. Rather, each of them is woven into the (mixed) fabric of the cosmos, becoming itself only as part of this melee. And so a world is born in a movement, not from difference to sameness, but from unrelated differences to their related mix—from plurality, one might add, to multiplicity.

Perhaps needless to say, however, this reading of Plato did not become the standard one.

The Oneness of the World: Aristotle’s De caelo

“Are we right then to speak of one universe,” Timaeus wonders aloud, “or would it be more correct to speak of a plurality or infinity?” (31a). The question, of course, is rhetorical; for Timaeus, the cosmos has to be singular in order to reflect the singularity of its model. This “model” is not the demiurge who shapes it, but the eternal Form of the “perfect living creature”—an ideal being that comprises all other ideal creatures and that for this reason must be unique. To be sure, insofar as this singular Form does contain all living creatures, it is also a vast multiplicity, as is the world that is modeled on it and made by means of it (35a). It is for this reason that Michel Serres says the Timaean cosmos is, in spite of itself, “a mix of mixes”—a “negotiation” of the same and the different, the eternal and the changing, the chaotic and the cosmic.35 Even though Plato often opens such floodgates onto multiplicity, however, he closes them as well—particularly when it comes to the question of cosmic eternity. We will recall that, for Plato, the oneness of the cosmos ensures the permanence of the cosmos; if there were other worlds bouncing around in some vast Atomist void, then one of them might collide with ours and destroy it.36 It is for this reason that Timaeus insists that (1) the god used up all the precosmic material in constructing the cosmos and that (2) “our universe was and is and will continue to be his only creation” (29e, 32c, 31a). In short, if the world is unique, then it is invulnerable to destruction or change—as long as the god maintains his “sovereign bond” to preserve it (41a–b). Here, as in the biblical tradition, oneness equals power—and both are secured by the sovereignty of God.

Plato’s concern over cosmic imperishability is reaffirmed in the works of Aristotle, who in the De caelo (On the Heavens) likewise declares the world to be “exempt from decay.”37 Unlike his teacher, however, Aristotle seeks to establish this permanence through natural law rather than through godly benevolence. In fact, he insists that the Platonic creator actually undermines the permanence of the cosmos—simply by creating the world. Reading the Timaean narrative literally, Aristotle is baffled by what he sees as the asymmetry of Platonic cosmology: as he explains in the De caelo, the world can be either (1) generated and corruptible or (2) ungenerated and incorruptible, but it cannot possibly be both generated and incorruptible at the same time (279b19–80a11). Any world that comes into existence must also go out of existence; in short, a universe with a temporal beginning cannot have an eternal future. (“This,” Aristotle writes parenthetically, “is held in the Timaeus, where Plato says that the heaven, though it was generated, will none the less exist for the rest of time” [280a30].) Of the two options that Aristotle has set forth (either generated and corruptible or ungenerated and incorruptible), he will opt for the second, which leads him to insist that the eternally existing world must be unique. “If the world is one,” he explains, “it is impossible that it should be, as a whole, first generated and then destroyed…. If, on the other hand, the worlds are infinite in number the view is more plausible” (280a24–28). Aristotle here is echoing Timaeus’s concern over the Atomists, whose teachings are addressed in chapter 2. Against these thinkers, who posited an infinite number of kosmoi, Aristotle’s task is to prove that there cannot be more than one of them, much less an infinite number of them. And, once again, the endurance of our cosmos is at stake: we can be sure the world will last forever only if it is ungenerated, and we can be sure it is ungenerated only if we know it is the only one.38

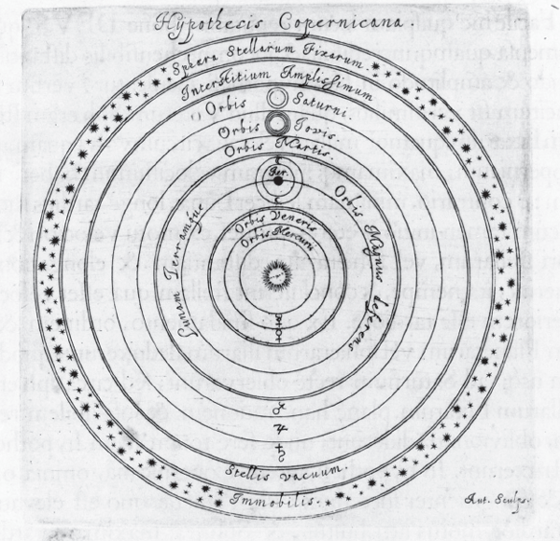

Aristotle establishes the singularity of the world by means of two distinct proofs. The first, found in the De caelo, is based on his theory of “natural motion,”39 which states that the elements of the universe move either “by nature” or “by constraint,” according to their properties. For example, inherently heavy things, such as earth, move downward by nature and upward by constraint. Inherently light things, such as fire and air, move upward by nature and downward by constraint.40 Each of the elements therefore occupies its own realm in the cosmos, which Aristotle demonstrates must be spherical.41 Because earth is the heaviest element, it moves “naturally” toward the center of this universe. As the lightest element, fire moves toward circumference of the universe, and air and water move between earth and fire. Unlike Timaeus, then, Aristotle does not describe the cosmos as a product of elemental mixing. Rather, his cosmos looks more like Timaeus’s “chaos,” with each element assigned to a separate realm: “earth is enclosed by water, water by air [and] air by fire,” so that the whole of “the heaven” is a sort of spherical nesting doll, eternally bounded by a rotating circle of stars (287a31). It is this vision that Ptolemy (ca. 90–168) will consolidate in the second century C.E. as the “geocentric” model of the universe, with the earth at the center, the sun and planets moving in concentric circles around it, and a ring of “fixed stars” that rotates around the earth every twenty-four hours (figure 1.1).

Having established the shape and arrangement of the cosmos, Aristotle goes on to demonstrate that this particular nesting doll must be the only one. He begins with the (poorly substantiated) premise that any hypothetical “other world” would have to be composed of the same substances as ours; otherwise, it could not be called a “world” (ouranos) at all (276a30–b10). This would mean that the elements of that other world would move the same way as ours: the hypothetical other-earth would move toward the center of the world, and the hypothetical other-fire would move toward its periphery. “This, however, is impossible,” Aristotle reasons, because in moving “down” toward the center of its own world, the other-earth would be moving “up” toward the periphery of our world. Likewise, in moving up toward its own periphery, the other-fire would be moving down toward our center. In short, both elements would be moving both up and down—naturally and unnaturally—at the same time (276b12–17, emphasis added).42 But insofar as “moving downward” constitutes the essence of earth as such, the other-earth’s upward motion with respect to our cosmos would make it not-earth. The same would go for fire; a downward-moving fire would not be fire at all. Thus “either we must refuse to admit the identical nature of the simple bodies in the various universes,” or we have to admit that there is only one center and one periphery, which is to say only one world. And because Aristotle (believes he) has already demonstrated that other worlds would have to be just like our world, “it follows that there cannot be more worlds than one” (276b21–22).

This one world, moreover, must be spatially limited, for, as we can see, the fixed stars rotate around the earth once a day. Because they always return to the same place, they cannot extend out to infinity; as Aristotle puts it, “a body which moves in a circle must necessarily be finite” (271b26). The “body” of the fixed stars therefore constitutes “the extreme circumference of the whole,” a firm boundary outside of which nothing else exists. Like Timaeus, then, Aristotle concludes that there is nothing beyond the world to threaten its eternity or its singularity; rather, “this heaven of ours is one and unique and complete” (279a10).

“A Somewhat Confused Interpolation”: Many-Oneness in the Metaphysics

A very different proof of cosmic singularity can be found in Aristotle’s Metaphysics. At first glance, this demonstration seems more straightforward than the argument from natural motion—if just as ridden with unsubstantiated premises. In the widely read Book Lambda of the Metaphysics, Aristotle stipulates that everything that moves must have a mover. But, he reasons, most causes of motion are subject to change or destruction—wind, for example, or hands or feet or anything with a body. So if the world as a whole is unchanging and indestructible (one of the unsubstantiated premises), then it must have some source of motion that is eternal and unchanging.43 This source must itself have no “magnitude,” or material extension, lest it be subject to division and change (1073a). Aristotle calls such an unalterable, disembodied force at the base of things the “prime mover,” “primary essence,” or “principle” (archê). It is this “principle” that anchors his second proof of the oneness of the universe, which here as elsewhere he calls “the heaven” (ouranos). The proof comes near the end of chapter 8 of the Metaphysics and proceeds as follows:

1. If there were many heavens, as there are many men, then

2. The principles for each heaven will be one in form but many in number.

3. But everything that is numerically plural has matter….

4. But the primary essence does not have matter…. So

5. The unmovable first mover must be both formally and numerically single. So

6. The permanent and continuous object of movement must also be single. So

7. There is one single heaven only. (1074a)

Again, the argument seems straightforward: because the eternal source of motion is immaterial, it must be singular. And because it is singular, the world it moves must also be singular. Therefore, “there is one single heaven only.”

The matter would seem to be settled, except this compact little proof comes directly on the heels of a very different argument. Earlier in the same short chapter, Aristotle begins with the premises that (1) what is moved must have a mover and that (2) this mover must itself be unmoved. To this, he adds the further premise that (3) “a single movement must be produced by something single” (1073a). So far, so good; this argument is what will allow him in a few pages to establish the singularity of the cosmos based on the singularity of its mover. But then Aristotle reminds us that this “single movement” applies not only to “the whole universe,” but to the “planetary courses” as well (1073a). And because each of the planets (or “stars”)44 is a substance, “it is clearly necessary that the number of substances eternal in their nature and intrinsically unmovable (and without magnitude …) should equal that of the movements of the stars” (1073a). What has happened here is that without justifying the leap, Aristotle has attributed to each planet the “single movement” of premise (3), declaring that there must be as many “single movers” as there are planetary courses. Then, through a perfectly inscrutable calculus, he goes on to reveal the number of courses to be either fifty-five or forty-seven, depending on how many spheres one attributes to the sun and the moon. Therefore, Aristotle concludes that the number of prime movers must likewise be either fifty-five or forty-seven, but then adds, “We will leave to more rigorous thinkers than ourselves the proof of all this!” (1074a).

Even the most rigorous of thinkers, however, would be incapable of offering such a proof—or even of understanding the next move the Metaphysics makes. Immediately after concluding the number of prime movers to be either fifty-five or forty-seven, Aristotle launches into the seven-step proof elaborated earlier, which shows that the world is one because its prime mover must be one. It is at this point that, in the words of translator-commentator Hugh Lawson-Tancred, “we pass from the sublime to the ridiculous.”45 Aristotle never reconciles these proofs, nor does he adjudicate between them, so we are left at the end of chapter 8 uncertain as to which of them to take seriously. If we were to accept the text at its face value, we would be able conclude only that there are a varying number of prime movers, depending on which elements of the cosmos they are said to be moving. One, forty-seven, fifty-five … it all depends on the way we count. Yet to borrow a Peripatetic turn of phrase, this is clearly absurd: if the prime mover is eternally unchanged, then its number cannot shift with the whims of human argumentation. So what is going on here?

In the Loeb edition of the Metaphysics, translator Hugh Tredennick suggests that the problem might just be one of poor editing. Chapter 8 seems to superimpose two strands of Aristotle’s writing: the chronologically “earlier” text asserting the singularity of the prime mover, and the “later” text numbering them at either forty-seven or fifty-five.46 Even if these texts are so superimposed, however, this explanation does not account for Aristotle’s failure at this “later” stage either to revise or to retract his assertions about the oneness of the cosmos. For if there are numerous prime movers, then according to Aristotle’s own logic there are two possibilities: either the number of the world does not reflect the number of the power that moves it, so that the world can still be singular despite its plurality of movers, or the number of worlds does reflect the number of movers, in which case there are either forty-seven or fifty-five worlds—one for each mover. And if each planet can be said to compose a world, then Aristotle would have to conclude that each planet is in effect its own “earth,” with its own center and periphery. But, of course, such a conclusion would violate the De caelo’s theory of natural motion by positing multiple centers and multiple peripheries—which is to say no center and no periphery. But as the De Caelo itself might respond, “This, however, is impossible” (276b12).47

Faced with the deeply incompatible arguments of this section of the Metaphysics, Lawson-Tancred throws up his interpretive hands: “The chapter is on any account vexed. Although attempts have been made to show its compatibility with the rest of [Book] Lambda, the consensus of opinion is that it is a somewhat confused interpolation.”48 But it is precisely this vexed and confused interpolation that makes the chapter so fascinating. What is most compelling, I would suggest, is the extent to which the chapter both reveals and covers over what one might call singularity’s constitutive plurality. In seeking to secure the absolute oneness of the cosmos, Aristotle stumbles upon its manyness and then tries to unfind what he has found. At first, this manyness is internal: in the process of establishing the eternity of the (singular) heaven, Aristotle recognizes that there are “other eternal courses, to wit those of the planets” (1073a). So the eternally singular cosmos contains an eternal plurality within it. But the very eternity of this plurality suggests that each planetary course must itself be “something single,” which means that each must have its own mover (1073a). It is at this point that plurality breaks out of its singular containment, for if each planet has a mover, then each planet must surely be a world in its own right. This would mean that our ball of earth, water, air, and fire would be a singular element within a broader plurality of other (singular) kosmoi. For some reason, however, Aristotle finds this conclusion so troubling that he not only recoils from it but recoils from it badly. Messily, illogically, he concludes simply by restating that the cosmos must be singular because the prime mover is singular, and in this way he (thinks he) puts the messy multiplicity to rest.

But, of course, the repressed never quite stays put. One sentence after the proof’s conclusion (“There is one single heaven only” [1074a]), Aristotle slips into a prosaic reflection on “tradition”—in particular, on the ancients’ “mythical” belief “that the stars are gods, and that the divine embraces the whole of nature” (1074b). Although he does not go on to say much of anything about this belief—simply that we know about it because it has been preserved through time—the notion that “the stars are gods” reopens the line of thinking that he closed off in his formal proofs. For here, in this mythological postscript, we finally find the possibility that each of the planets/stars might correspond to its own mover and thus to its own world. Here, too, we can glimpse one way through the clash that Aristotle has unwittingly staged between the singular and the plural. He tells us the ancients believed “that the stars are gods, and that the divine embraces [periechei] the whole of nature” (1074b, emphasis added). That is to say, the divine is many (as numerous as the stars), and the divine is also one (embracing, encompassing, surrounding all of nature). The divine, one might say, is singular-plural: multiple. And what if the same were true of the world? Might it be that worlds are as singular-plural as the gods that get them going? This is more than Aristotle is willing to contemplate, but then again, it is his text that brought us here.

Just like the Timaeus, the Metaphysics thus insists on the oneness of the cosmos, only to run up against an irreducible multiplicity. If Plato’s response to this multiplicity is a complex “negotiation,” then Aristotle’s might be seen as more of an allergic reaction.49 In both cases, however, these tenuous openings have been collapsed by “tradition”: the received reading has become simply that Plato and Aristotle believed the cosmos to be singular.

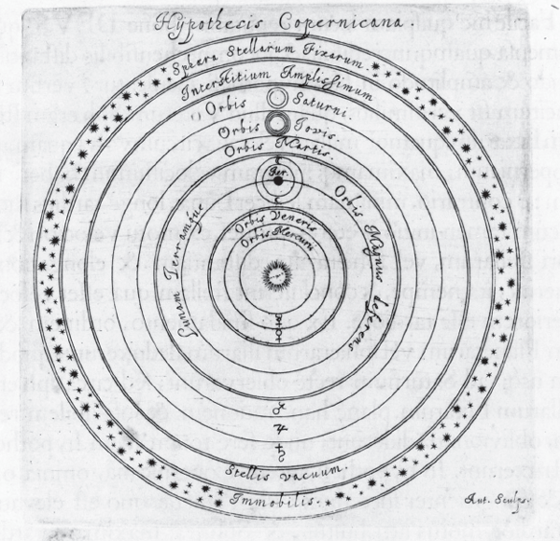

This Western enshrinement of cosmic singularity is largely the function of Ptolemy’s second-century consolidation of the “classical” cosmos: a geocentric set of circles bound by a ring of “fixed stars” (see figure 1.1). As Apian’s illustration and many other late-medieval diagrams attest, Ptolemy’s model was largely unrivaled until the mid-sixteenth century, when Copernicus posited his heliocentric model of the universe (figure 1.2).50 But even Nicolaus Copernicus, whose cosmology would turn the Christian West upside down in the hands of Galileo Galilei, still assumed that the cosmos was bounded by a ring of fixed stars, which is to say he assumed it was both finite and singular.51 Galileo refused to weigh in on the matter, suggesting that astronomy confine itself to the one world that it could see. If we were following the most straightforward path through the history of science, we would then move to Johannes Kepler, whose seventeenth-century discovery of elliptical orbits vastly improved the predictive power of heliocentrism, yet who insisted that “this world of ours” (1) has a definite boundary and (2) “does not belong to an undifferentiated swarm of others.”52 From Kepler’s reaffirmation of a finite and singular cosmos, it would then be a quick step to Isaac Newton’s “absolute” space and time, which arguably undermined his (eventual) belief in an infinite universe.53 And at the dawn of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein would cling to Newton’s cosmic fixity even as he abolished it, establishing space-time as a plastic set of shifting relationships, but nevertheless believing the universe as a whole to be eternal and unchanging and to consist of nothing more than our Milky Way.

From Plato to Einstein, then, the dominant assumption has been that our cosmos “was and is and will continue to be” the only one.54 Beneath this linear reign of singularity, however, there seethes a far more complicated story—a series of bold openings, frightened foreclosures, and radical retrievals of cosmic multiplicity—that makes the modern turn to the multiverse look a bit less sudden and certainly less unprecedented.

1

1