ankh A hieroglyph and symbol for “life.” It is represented by a sandal strap in the shape of a cross with a loop at the top.

Apis bull A bull deity that was an important sacred animal in Egypt. Its shrine resided in Memphis, where the deity protected the king and the residence; a massive cemetery for Apis bulls is located at Saqqara and called the “Serapeum.” The Apis bull was a symbol of the pharaoh and the qualities of kingship.

block statues A unique type of Egyptian sculpture that first appeared during the 12th Dynasty. The subject (almost always male) squats on the ground with his knees drawn up to his chest. In one type, arms, legs, and torso are enveloped in a cloak providing space for inscriptions.

Christian Period The earliest history of Christianity in Egypt is poorly known, although it is traditionally believed that Saint Mark founded it in 33 CE. By the fourth century CE, many groups seem to have arisen as true Christian churches and the city of Alexandria became one of the great Christian centers.

Coptic The last stage of Egyptian hieroglyphs that was written using an adapted Greek alphabet, with six letters leftover from the earlier Egyptian demotic script. It was associated with the rise of Christianity in Egypt and flourished from the first to 13th centuries CE.

demotic Developed from hieratic, the demotic script was the most cursive script in Egypt that represented the “popular” use of the Egyptian language. It occurs from the 26th Dynasty to the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods.

djed pillar A hieroglyph and symbol for “stability.” It is thought to represent the spine of Osiris, god of the underworld, with whom it was associated.

faience More correctly known as “Egyptian faience,” this blue-green glaze is a nonclay ceramic of silica made from sand or crushed quartz. It was commonly used to make jewelry, amulets, scarabs, figurines, and vessels.

funerary temple Also called mortuary temple. A temple dedicated to commemorating the cult of the deceased king and the reign of the pharaoh who commissioned its construction.

hieratic The cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphs used for everyday writing on papyri and ostraca as early as the First Dynasty. Young scribes learned to write hieratic before hieroglyphs.

hieroglyphs The Greek name for the main writing script of the ancient Egyptians, which consisted of picture characters (pictograms, or sense signs) and phonograms (sound signs) and was largely reserved for monumental objects and buildings, such as tomb and temple walls.

Predynastic Period (4500–3100 BCE; Neolithic and Dynasty 0) Before Egypt became a unified state governed by one ruling king, it was divided into two parts: Lower Egypt (in the north) and Upper Egypt (in the south). In each area, independent village settlements and cemeteries arose along with the development of agriculture and the domestication of animals.

Ramesside Period (1295–1070 BCE; Dynasties 19–20) When the Delta-born vizier and military leader Paramessu arose on the throne as Ramesses I, he began a new line of kings, many of whom continued to be named Ramesses. The Ramesside kings are known for their extensive building programs and military prowess.

relief A sculptural technique used for the decoration of wall scenes and inscriptions on monumental stone buildings (temples and tombs). In ancient Egypt, it came into widespread use during the Fourth Dynasty and consists of images and inscriptions that often covered entire walls of rooms in buildings. Relief can be raised (bas-relief) or sunk (incised).

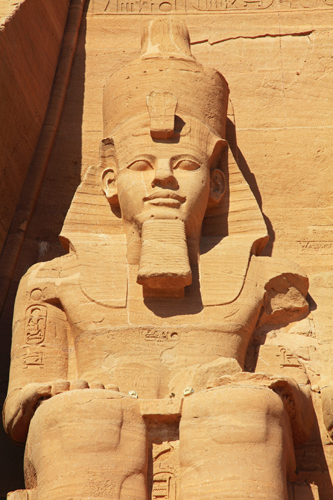

rock-cut temple Temples that were cut entirely into rock cliffs, such as the temples of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel, or had rock-cut inner chambers.

scarab An amulet in the form of a scarab beetle, associated with certain aspects of the sun god. Scarabs were generally inscribed on the bottom and were often incorporated into jewelry or used as administrative seals.

sistrum An ancient type of rattle used as a ceremonial instrument. It consisted of a metal hoop frame that held rings and bells, which made noise when the handle was shaken. The sistrum was associated with the goddess Hathor and was used by the priestesses of her cult to evoke protection, divine blessing, fertility, and rebirth.

sphinx A mythical creature with the body of a lion and the head of a man (or in some cases a ram), which often wore the royal nemes headdress. In Egypt, the most famous sphinx is the Great Sphinx at Giza.

Scenes of music making are found as early as the Prehistoric Period, accompanying all facets of life. The god Bes, associated with childbirth, is often seen playing a harp or shaking a tambourine. In a folk story, the arrival of royal children is concluded by “the sound of singing, music, dancing, and exultation.” Banquet scenes show orchestras accompanying a singer holding his hand to his ear to be sure of correct pitch. A love poem invites a maiden’s sweetheart to “Come to me with beer and singers equipped with their instruments”; such odes were meant to be sung along with a harp, lyre, or flute. Liturgical scenes often show musicians, dancers, and singers; the last would have been trained in local schools, one of which—the Memphis School of Music—was famous in the Ramesside Period. Even field hands were entertained by musicians while working in the countryside. At the end of life, elaborate funerals included vigorous dancing, while funerary banquets included flautists, harpists, and people clapping. Percussion instruments comprised drums, tambourines, rattles, sistra, and hand clappers. Wind instruments consisted of flutes, clarinets, oboes, and trumpets. Stringed instruments were the harp, lyre, and the lute. Musicians must have learned and played by ear, because no written music has survived from antiquity.

From birth to death, music, singing, and dancing were an integral part of ancient Egyptian life.

Trumpets are mostly shown in scenes of warfare. The two found in Tutankhamun’s tomb were simple metal tubes made of silver and copper, respectively. Their range was so limited that they were probably only used rhythmically, playing single notes. In another military context, the ancient Roman author Virgil (Aeneid, 8) describes Queen Cleopatra shaking a sistrum while rallying her troops at the Battle of Actium.

Ronald J. Leprohon

The ancient Egyptians played a variety of instruments, including lyres and flutes. Musicians played a part in funerary banquets.

Hieroglyphs, “sacred engravings,” are the ancient Egyptian writing system used from around 3250 BCE to 394 CE. The earliest examples come from a royal tomb at Abydos. Written on small ivory or bone labels attached to linen bags found in the tomb, the signs were used to indicate the quantity, provenance, or ownership of the goods. Because hieroglyphs were devised to write names and titles, their original purpose may have been administrative. A cursive form of hieroglyphs known as hieratic, which was quicker to draw on papyrus, developed at the same time. By the seventh century BCE, hieratic had evolved into demotic, an even simpler script. Hieroglyphs used the rebus system, which writes out the sounds of the language using pictures. Words written phonetically were complemented by sense signs, which helped readers determine the concept of the word; for example, a homonym such as henu, could be accompanied by the people sign to write the word “neighbors” or a jar for the word “measure.” During the Christian Period, Greek letters were used for Coptic, the last stage of the Egyptian language. In 1822, the linguist Jean-François Champollion deciphered hieroglyphs by using Greek and Hebrew sources to recognize Egyptian proper names on the Rosetta Stone.

Egyptian hieroglyphs used phonograms to write out the sounds of the language. Other scripts employed were cursive versions known as hieratic or demotic.

Egyptian hieroglyphs could be written vertically or horizontally from right to left or left to right. The clue to the direction of reading is given by the signs themselves: hieroglyphs that face right indicate a text to be read from right to left and vice versa. In a scene on a temple or tomb wall showing figures facing one another, the accompanying captions change direction to suit the orientation of the figures.

JEAN-FRANÇOIS CHAMPOLLION

1790–1832

French linguist and Egyptologist

GÜNTHER DREYER

1943–

German archaeologist, discoverer of Tomb U-j at Abydos

Ronald J. Leprohon

The Rosetta Stone contains the same text, in Greek and in two forms of Egyptian. In 1822 the inscription provided the breakthrough to deciphering hieroglyphs.

Nothing survives of the literary output from earlier periods, but the Middle Kingdom produced historical fiction, instructional material, and tales of magic, adventures abroad, a marooned sailor, and a peasant wronged by rapacious officials. The best of these works is The Story of Sinuhe. Set in the early 12th Dynasty, it tells of a royal bodyguard who deserts his post, flees to the Levant, and eventually returns to Egypt after being pardoned by the king. It was so popular that copies were transcribed, mostly on papyrus, for a full seven centuries. The New Kingdom brought tales of the gods and stories with well-known literary motifs. In The Taking of Joppa, a general ends a siege by hiding soldiers inside baskets disguised as gifts for the city. The hero of The Doomed Prince is confined in a tower to avoid the fate predicted for him by seven goddesses; he then journeys to the Levant, where he fabricates a story about an evil stepmother who wishes him harm, magically wins the hand of a princess in a tower, and is saved by her love. The Two Brothers tells of an older woman who attempts to seduce a younger man; when he refuses, she pretends to have been attacked, like Potiphar’s wife in the Old Testament.

Literature, in the form of tales, poetry, and instructions, was used to entertain, educate, propagandize, and tell stories about the divine and everyday worlds.

Ancient Egyptian stories were meant to be heard instead of read. Puns and alliteration, themes grouped in couplets, and phrases couched in specific rhythms betray their oral origin. In a series of tales preserved in the Westcar Papyrus, an evening of storytelling at a royal court has each recitation begin with the phrase: “Then Prince [name] rose in order to speak, and he said …”

PENTAWER

ca. 13th century BCE

A king’s scribe famous for writing down the “Poem of Kadesh”

RICHARD B. PARKINSON

1963–

British Egyptologist; specialist in ancient Egyptian literature

Ronald J. Leprohon

Literature ranged from educational texts to narrative tales. Popular stories, such as The Two Brothers—a tale of seduction—were recorded on papyrus by scribes.

Sculptors used hammers to work granite and quartzite, and chisels for carving limestone, alabaster, and wood. Copper-clad wooden statues and figures cast in gold and bronze were also produced. A grid enabled sculptors to adhere to standardized proportions. Wooden statuary was made in pieces pegged together. A stone statue started as a squared-up block with front, profile, and back views of the figure drawn on the sides. Back pillars and back slabs are structural features typical of stone statuary, like “negative space,” stone left standing between limbs and torso. The subject’s name and titles were inscribed on the base and statues were painted unless they were made of skin-colored materials. Men, whether king, god, or commoner, were depicted striding forward, left leg advanced, grasping accessories that signaled their status. Women were customarily shown standing with their feet together, hands open at the sides. Scale in group statuary usually reflected nature; wives were shorter than their spouses and children smaller yet. Only men owned scribe statues—which documented membership in the literate elite—and block statues. Introduced in the Middle Kingdom, block statues remained popular for centuries. Sphinxes flanked processional avenues and guarded entrances to sacred precincts.

A statue enabled its subject, whether a god, a king, or a commoner, to exist in a tomb or temple and to benefit from the cult practiced there in perpetuity.

Figures fashioned in clay and carved from animal tusks were created well before the unification, but the earliest evidence for stone sculpture dates to late Predynastic times. Limestone fragments from Hierakonpolis include an ear and a nose, while larger than life-size statues of the fertility god Min discovered at Coptos demonstrate that gods were already made in the image of man by the time of Narmer at the latest.

HANS GERHART EVERS

1900–1993

His 1929 study of Middle Kingdom royal sculpture is a methodological milestone

JACQUES VANDIER

1904–1973

Volume 3 of his Manuel d’archéologie égyptienne (1957) provides an excellent introduction to ancient Egyptian statuary

M. Eaton-Krauss

Statues were made from wood or stone. The Giza sphinx is the largest freestanding sculpture in the ancient world.

In 1976, 3,200 years after his death, the mummy of Ramesses II was welcomed with full military honors when it arrived in Paris to undergo treatment to prevent further deterioration. The style of his reception shows how the king’s reputation, which he had carefully bolstered over a 66-year reign (1279–1213 BCE), had survived into Classical antiquity and on into 19th-century Romanticism, when Percy Shelley wrote his famous sonnet “Ozymandias.”

Ramesses II’s building activity surpasses that of all other Egyptian kings and extended from the Levant to the Sudan. Most significant were the residence city of Piramesse in the eastern Nile Delta, a string of forts on Egypt’s western border to counter the military threat posed by the Libyans, subterranean catacombs for the burial of the sacred Apis bulls in Saqqara, a temple for Osiris at Abydos, additions to the temples of Karnak and Luxor, the king’s tomb and a gigantic mausoleum for his dozens of sons in the Valley of the Kings, a large funerary temple (the Ramesseum), and the two rock temples of Abu Simbel in Nubia. Ramesses also usurped hundreds of earlier monuments and statues. A marked departure from tradition was the extent to which the king had himself worshipped as a god during his lifetime. The king’s aspirations to regain control over Middle Syria failed when he was defeated by the Hittite king in the famous Battle of Kadesh in 1275 BCE. The texts and depictions of the battle present the king and his god Amun as victorious over their Hittite enemies, a unique religious and literary document disseminated in multiple copies, both on temple walls and papyri. In 1254 BCE, the two empires concluded the first preserved peace treaty in human history, a replica of which is today on display at the United Nations headquarters in New York. Parts of the correspondence exchanged between the two courts dealt with Ramesses’ marriage of two Hittite princesses, a state visit from the Hittite crown prince, and medical aid. From Hittite records we know that Egypt also provided the Hittites with supplies of grain and helped them to build a naval fleet.

The most famous of Ramesses’ principal wives was queen Nefertari, who owned a magnificent tomb in the Valley of the Queens. Of the king’s sons, the most important were his fourth son, Khaemwese, a scholar who directed much of his activities toward the study and restoration of the monuments of Egypt’s past, and his 13th son, Merenptah, who assumed the throne after the king’s death.

Thomas Schneider

Conventions of two-dimensional art developed concurrently with the hieroglyphic script; there was but one word for both scribe and painter. Characteristic views of a subject were combined to create a “complete” impression of it, most notably in rendering human figures with one frontal eye in a head drawn in profile. The shoulders are also frontal, but the trunk is in profile. The first and last steps in creating relief lay in the hands of draftsmen-painters, who drew figures according to a standardized canon of proportions and composed scenes in registers. When sculptors finished carving, painters brought the reliefs to life by adding color; finally, they outlined the figures to give them prominence. Strong, flat color was the rule, applied as dictated by convention: women’s skin was yellow, men’s red-brown, and the hair of both sexes was black. Status determined scale—gods and kings towered above priests and servants. Interiors were carved in raised relief to catch the light; sunk relief was used for exterior surfaces exposed to the sun. Draftsmen had to use a grid to draw figures of the owner and his family on tomb walls and those of the king and gods in temples, but they could and did give full rein to their creative impulses when designing and coloring subsidiary figures, flora, and fauna.

Painted relief was preferred for decorating temples and tombs, because its long-term chances of survival were higher.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, archaeologists excavating settlement sites discovered evidence for paintings not only on walls inside palaces and the homes of commoners—flora and fauna of the marshes and domestic scenes—but also on the exterior (swags and abstract designs). The tradition of decorating the whitewashed exterior of mud-brick dwellings is still practiced in villages along the Nile today.

HENRY GEORGE FISCHER

1923–2006

Published fundamental studies on the relationship between the hieroglyphic script and ancient Egyptian two-dimensional art

M. Eaton-Krauss

Artists had to follow a set of conventions and work to a grid, but they were allowed creative freedom in the depiction of minor figures and of details, such as flora and fauna.

Ancient Egyptians valued appearances. The well-to-do spared no expense in adorning themselves and their homes with beautifully decorated, status-signifying apparel and accoutrements. Fine linen kilts, tunics, and dresses could be intricately draped and pleated, or decorated with embroidered or applied designs. The customarily white clothing provided a perfect backdrop for multicolored jewelry, including beaded broad collars, rings, bracelets/anklets, and necklaces inlaid with semiprecious gems. While these items were too costly for average Egyptians, protective amulets, made of faience, shell, bone/ivory, copper/bronze, and various stones, were popular among all social classes. Amulets depicted deities, sacred animals, parts of the body, or hieroglyphs (such the ankh or the djed pillar). The most ubiquitous shape for amulets was the scarab beetle, associated with the regenerative power of the sun god, and therefore popular in both everyday and funerary contexts. Clothing and jewelry were stored in brightly painted boxes inlaid with ivory and ebony or ornamented with hieroglyphs. Furniture sometimes had carved and/or gilded elements representing animals or plants. Ceramic vessels could be painted or otherwise embellished, particularly during the Predynastic Period and the New Kingdom.

Besides exquisite paintings, reliefs, and statuary, the ancient Egyptians often fashioned items for personal adornment and practical use that were themselves minor works of art.

The term “minor arts” (aka “decorative” or “applied” arts) traditionally refers to the design and production of utilitarian objects, as opposed to “fine arts” (such as painting and sculpture), which are considered to have no objective purpose other than aesthetics. However, this distinction between minor and fine arts is largely a modern Western construction, and can be somewhat misleading when applied to ancient Egypt, where all “art” was created to be, in some manner, functional.

Rachel Aronin

Elaborate, multicolored jewelry was designed to stand out against the white clothing worn by the rich.