Figure 10.1.Culture regions of the United States. Image by author.

Chapter 10

Cultural geography–folk and popular culture, language, religion

One of the most significant forces that shapes human society is culture. It affects how people think and act, how they transform landscapes, and how they relate to other social groups. Linguistic, religious, and cultural norms shape peoples’ identities, regions, and sense of place, giving each locale its unique character. It is largely because of diverse cultural landscapes that we love to travel: sights, sounds, and smells vary from place to place because of cultural differences.

Culture is often divided into two broad categories: material and nonmaterial. Material culture involves things we can sense, be it hearing music, tasting food, or seeing architecture. Nonmaterial culture involves the things in our heads, such as religious beliefs and the way language structures our views of the world.

Human culture, both material and nonmaterial, undergoes constant change. As humans migrate and communicate between places, new cultural traits arise from the constant borrowing and stealing of ideas. This exchange affects musical styles, architectural design and building techniques, culinary habits, religious views, ways of speaking, and much more. Although modern transportation and communication have shrunk the world in a sense, allowing cultural traits to diffuse rapidly from one place to another, places still retain their uniqueness. Indigenous culture and traditions remain a powerful force, resulting in local adaptations of global trends.

Culture regions

In chapter 1, you were introduced to the concept of regions and how they can be identified as formal, functional, or perceptual. In the context of culture, formal and perceptual techniques are commonly used to identify regions. Formal regions are often differentiated by mapping some commonality, such as ethnicity, language, religion, or other aspects of culture. At the same time, perceptual regions can be identified by surveying what name people use for where they live and how it contrasts with the names used for surrounding areas. Thus, regions represent places with common cultural habits, beliefs, ways of life, and cultural landscapes.

We use culture regions as shorthand to describe places, visualize them in our mental maps, and simplify the world for purposes of analysis. Globally, for instance, geographers and others often write about the Middle East on the basis of its geographic location. This region often includes countries around the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula as well as those forming a crescent around the eastern Mediterranean Sea from Turkey to Egypt. Other writers focus on the Arab world using ethnicity and language to identify a region. This focus overlaps with much of the Middle East but is distinct. It includes countries such as Morocco at the far western edge of North Africa but excludes Israel, Turkey, and Iran. Still others may use religion as a unifying regional criterion by examining the Islamic world. The Islamic world is much broader and includes the Muslim nations stretching from North Africa through the Middle East to part of Central, South, and Southeast Asia.

Culture regions are also identified at a more local scale. Within Europe, we can talk about Scandinavia, the Iberian Peninsula, the Mediterranean, the British Isles, Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and more. Each of these European regions stands apart from the others because of characteristics such as language (Slavic, Germanic, Romance), religion (Catholic, Protestant, Eastern Orthodox), history, and more. Based on these differences, we can see cultural landscapes that vary in terms of architectural styles, social differences in terms of family and social life, and political difference in terms of government and institutions.

Culture regions in the United States

As can be imagined, a large country such as the United States can also be divided into distinct culture regions (figure 10.1). For instance, the geographer Wilber Zelinsky, in 1980, published an influential article on the fourteen vernacular regions of the United States. These regions, such as Dixie, Pacific, and Midland, were identified through an analysis of regional words used in businesses, schools, churches, and other organizations. Zelinsky’s paper did not detail how each region’s culture was unique, but other authors have analyzed regional differences by subregions similar to his. Based on these analyses, differences become apparent in the way people speak, their religious beliefs, foods, architecture, social behavior, and much more. For instance, we are all familiar with regional accents, be it a Texas twang, a southern drawl, a New York accent. We also know that foods vary substantially, with fried okra in the South, spicy Tex-Mex in Texas, and clam chowder in New England.

Figure 10.1.Culture regions of the United States. Image by author.

What we may be less familiar with is how the historical evolution of each region impacts aspects of culture. For instance, much of New England and the Northwest was originally settled by Calvinists, who valued work for the common good and a greater denial of self. This cultural trait has survived for hundreds of years, so that the political culture still gives stronger support to government social programs than in many other regions of the United States. This lies in direct contrast to the South and its northern border in Appalachia. There, historical settlement patterns led to populations that favor individual liberty and that resist federal intrusion from Washington, DC. In Appalachia, this came from immigrants from the borderlands between Scotland and England and between Northern Ireland and Ireland. These conflict-ridden regions in the British Isles helped create a warrior-ethic culture that resisted those in power, characteristics that are still common to this day. In the South, early settlement was modeled after the slave societies of the Caribbean Basin. It was based on power for a small elite and disenfranchisement for most of the rest of the population. As the elite did not need government assistance, and the disenfranchised were excluded from political decision making, a culture that resists taxes and other government interference remains a strong force.

Another interesting regional difference in the United States relates to violence. Since the colonial era, violence has been higher in the Appalachian and Southern regions than in regions such as New England where Puritan society put priority on societal order. The state dealt harshly with violent acts, creating an institutional and cultural framework that kept it under control. In contrast, Appalachia’s warrior ethic led to a culture of clan and family loyalty, with a high value placed on exacting vengeance when honor was violated. The South, too, had a relatively high tolerance for violence. There, violence was sanctioned culturally, and individuals used it to a greater degree than the state. It was also tied to honor, but it had a hierarchical component as well. Superiors used violence against inferiors, husbands used it against wives, and parents used it against children.

Regional cultural patterns of violence reach from the colonial past to the present. In 2014, the states with the highest homicide rates were in the South: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Arkansas. In fact, the homicide rates in Louisiana and Mississippi were nearly seven times higher than in Massachusetts. Some research has even shown that homicide rates correlate more strongly with cultural region than with poverty, urban density, or other material variables.

Tapestry segmentation

Broad culture regions still have a strong influence on how people think and act in the United States, but with changes in communication and transportation, regional differences have become somewhat more blurred. Northerners move to the South, Southerners move to the West, and Westerners move to the Northeast. As people move, they bring their regional cultures with them but also absorb elements of the region to which they move. People across the country can also see the same television shows, web pages, and social media, regardless of the region in which they live. Thus, in many ways, cultural differences can now vary more by urban or rural location, income and education, age, ethnicity, or other demographic and socioeconomic factors. We still form clusters with other like-minded people, but often at more local scales.

Tapestry Segmentation, first mentioned in chapter 4, identifies places with common characteristics along social, economic, and demographic lines. It divides neighborhoods in the United States into fourteen broad Life Mode groups, which are further divided into sixty-seven more detailed tapestry segments. The logic behind segmentation analysis is that people with similar tastes and behaviors cluster in specific places. Our political and social beliefs; the food, clothing, and other items we buy; and the music we listen to tend to be like that of our neighbors. Where we grow up influences us, and when we move, we tend to choose places where others think similarly.

At a county level, clear Life Mode clusters are seen, but they are not always confined to traditional culture regions (figure 10.2). The Rural Bypasses segment is largely clustered in the South, but the Soccer Mom segment is found in suburban communities throughout the country. In the largely Southern Rural Bypasses counties, people live in rural and small-town places where incomes are relatively low, as are levels of education. Values are traditional, and religion is a central part of people’s lives. Outdoor activity such as hunting and fishing is popular, and people prefer trucks over sedans. The South contains a substantial number of Soccer Mom communities as well, but these are also found scattered throughout the country. Here, people live in higher-income suburban communities. Those with college educations are more prevalent than in surrounding rural areas, and technology is heavily integrated into their lives. Outdoor activities consist of those common to suburban communities, such as jogging, bicycling, golfing, and boating as well as target shooting.

Figure 10.2.Culture regions: Segmentation analysis. Explore this map at https://arcg.is/1ai4SG. Data sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, NGA, USGS, US Census Bureau, Infogroup.

Thus, cultural regions can be seen at different scales, from the broad region to smaller neighborhoods. Regardless of the scale, people with common beliefs and behaviors often cluster with other like-minded people, creating cultural mosaics on the landscape.

Folk and popular culture

Geographers often divide culture into two broad categories: folk and popular. Folk culture originates in more isolated and homogenous societies. Music, food, building styles, and other components of material and nonmaterial culture develop organically in folk cultures. There is no author, designer, or inventor; rather, culture evolves from the shared life experiences of the group and the natural environment in which they live. There is no copyright or patent on folk artifacts, but instead traditions pass orally from person to person and generation to generation as common knowledge.

Popular culture, on the other hand, develops in larger, more heterogeneous societies. Typically, the person or group that creates the cultural artifact, be it a song or a building, is known. Copyrights and patents are common, allowing creators to gain fame and wealth from their creations. Popular culture, as its name implies, diffuses widely and is not tied to a specific place or environment.

Music: From Appalachia folk to New York rap

Folk music, as with all folk culture, is music passed on through oral tradition, with origins in rural communities. It is not written but rather is learned via exposure to others in a social group. Consequently, folk songs can change over time, as people add and subtract material to suit changing circumstances. In the United States, the Appalachia region was a source of much research on folk music. Early-twentieth-century researchers sought to collect and catalog folk songs from this region because of the relative isolation of many communities in remote mountain and valley settlements that had limited exposure to urban cultural influences. The Appalachian culture consisted largely of folk traditions from the English and Scots of the British Isles who had migrated and settled there in eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

As Western society urbanized, folk traditions weakened. Mass communication and mobility meant that people increasingly shared culture, including musical styles. Radio allowed music to be heard across wide areas; thus, folk music began to transform into popular music. Traditional folk instruments, rhythms, and lyrics were incorporated into music aimed at wider audiences. Gaining wider audience appeal often involved adding political and social movement themes to songs, supporting the folk, or common people, and their struggles in modern society.

The origin and diffusion of rap music illustrates how folk traditions blend into new forms of popular music. African folk customs diffused to the Americas with the forced migration of the slave trade. Many of these traditions, including those of griots, or traditional West African storytellers/singers, remained integral parts of African American life. Along with other musical traditions, it evolved into blues, jazz, and R&B. By the 1970s, these influences, along with a Jamaican tradition of speaking over beats, began to take form as rap in isolated African American urban neighborhoods. This blending of musical styles is known as syncretism, the process of combining cultural traditions into a new form. Thus, rap music is based on syncretism of African, Caribbean, and African American musical traditions.

Rap followed a classic pattern of hierarchical diffusion. It originated in New York City, and through the 1980s, this was its clear cultural hearth, led by groups such as The Sugarhill Gang, Grandmaster Flash, and others. By the 1990s, Los Angeles had become an important source of new rap talent, second only to New York, where Ice T and Easy-E’s debut albums were seeing huge sales. Following New York and Los Angeles, new rap artists gained traction in other large and medium-sized urban areas, such as New Orleans, Houston, Oakland, Atlanta, Chicago, and Detroit. By the 2000s, artists were gaining popularity in a number of cities outside of the coastal cities and the handful of larger cities where rap first had success.

From its origins in segregated neighborhoods of New York City, rap is now a global phenomenon. In many ways, it has become a lingua franca, or common language, for youth around the world. Rap competitions can now be found in Shanghai, China; Paris, France; Moscow, Russia; Cape Town, South Africa; and major urban areas on every continent (figure 10.3).

Although it is considered popular music enjoyed by people across the country and around the world, rap has strong associations with specific places. Sense of place is an important component of the genre, so that where the rapper is from advances or hinders his/her street cred and, ultimately, fame and fortune. Typically, coming from a poor inner-city neighborhood grants authenticity, something that Eminem, from inner-city Detroit, had but Vanilla Ice, from a more suburban location, did not. Rivalries, often promoted by record labels, have often been tied to geography, pitting neighborhoods, cities, and regions against one another. These place-based rivalries resulted in homicide for some, such as Tupac and Notorious BIG in the 1990s East Coast–West Coast feud.

Figure 10.3.A Russian rapper performs in Moscow. Rap evolved from folk traditions to a global popular culture phenomenon. Photo by: Hurricanehank. Stock photo ID: 681052426. Shutterstock.com.

Food: Beef and potatoes to Subway

As with music, culinary traditions can be seen in terms of folk and popular culture. Folk foods are closely tied to local physical environments, whereby people’s diets are based on the foods and animals that thrive in their locale. With the advent of agriculture, farm crops and animals quickly diffused to new places. Through trade and migration, they spread from origin points across continents and, ultimately, around the world. Thus, foods considered folk in nature do not necessarily originate in the place in which they are consumed.

Food has a strong association with place and often forms an important part of people’s regional identities. For example, collard greens originated in the eastern Mediterranean region but thrived in the Southern climates of the United States. Dishes with collards are now promoted in restaurants as “traditional cooking” and “soul food,” reflecting their long history in that region. In the Great Plains region of the United States, beef, potatoes, and bread constitute folk meals, although none of these items originated in North America; wheat and cattle originated in the Old World, and potatoes are from Andean Latin America. In many ways, foods of the Great Plains are seen as “American food,” although in reality, they represent diets of a region stretching from Montana south and eastward through Kansas. Even dominance of the all-American apple pie has a limited spatial distribution. Moving to the southern plains of Oklahoma and Texas, one crosses the “Apple pie line,” beyond which desserts begin to include peach cobbler and Mexican-influenced flan (a custard with caramel sauce) and sopapillas (fried dough with sugar and cinnamon).

In Tijuana, Mexico, a large border city just south of San Diego, California, some restaurants now promote folk foods that represent “Mexicanness.” In a region that is often dominated culturally and economically by its large northern neighbor, traditional Mexican dishes serve as a means of reasserting cultural boundaries. Traditional foods from rural haciendas consumed by the Spanish-indigenous mestizo population are promoted as an alternative to European influences among the elite and Americanized versions of Mexican food. In these restaurants, one does not find tacos, chimichangas, and enchiladas. Rather, maguey worms and champolines (grasshoppers), squash blossoms, nopal (cactus), and other traditional ingredients are used to prepare dishes tied to folk customs (figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4.Folk foods in Tijuana, Mexico. Here, mezcal red worms (also known as chinicuil, maguey worms, and gusano rojo) are served with traditional Mexican tlacoyos, a stuffed corn dough. Photo by VVDVVD. Stock photo ID: 639126400. Shutterstock.com.

In contrast to folk foods are popular culture foods—those marketed and consumed over wide areas by diverse populations. Soda such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi, fast-food restaurant chains such as McDonald’s and Subway, global food conglomerates such as Nestlé and General Mills, all produce for mass markets. Companies in the mass-market food sector operate in countries around the world, selling products that are often developed, manufactured, and marketed far from the place in which they are consumed.

Subway, in 2017, was the largest restaurant chain in the world, with over 44,000 stores in 111 countries (figure 10.5). McDonald’s is also found in over 100 countries, and Nestlé sells its products in nearly 200. Coca-Cola is sold in over 200 countries, and it claims that its logo is recognized by fully 94 percent of the world’s population!

Some argue that these types of companies contribute to placelessness. If one can travel the world and continue to drink Coca-Cola and eat at McDonald’s, so the argument goes, then why bother traveling? Others argue that global companies that ignore local cultures are doomed to fail. Just because a business model and product work in one culture does not mean it will work in another. Therefore, companies must use a strategy of glocalization. This somewhat awkward portmanteau combines globalization with localization. The idea behind it is that global companies must consider local cultural differences if they are to succeed. Despite the concerns of critics, local culture is still a powerful force that drives what people consume. Just like Southerners, residents of the Great Plains, and Tijuanenses have different culinary traditions, so too do people in all regions.

Figure 10.5.Number of Subway sandwich restaurants. Explore this map at https://arcg.is/0KKvGj. Data source: Subway.com.

Successful global companies have embraced glocalization. Nestlé Kit-Kats, for instance, come in cherry blossom, green tea, and strawberry cheesecake flavors in Japan (figure 10.6). Pringles potato chips in Asia include soft-shell crab flavor, and Oreos in Argentina come in dulce de leche (a type of caramel). One of the most successful companies to use glocalization is McDonald’s. Its traditional menu of burgers and fries is substantially modified around the world, so that you can order a pulut hitam (black rice pudding) pie in Korea, vanilla McNuggets in Taiwan, and an Eggcellent Silly Double Beef Burger (with an egg on top) in Hong Kong. Likewise, beef and pork are off the menu in India in deference to its large Hindu and Muslim populations.

Figure 10.6.Glocalization of Kit-Kat candy in Japan. Flavors come in cherry blossom, green tea, and strawberry cheesecake. Photo by Gnoparus. Stock photo ID: 366302453. Shutterstock.com.

Cultural foodways still exert a powerful influence in human culture, and culinary folk traditions remain strong and integral parts of many people’s identities. For this reason, even in the complex web of social and commercial interactions brought about through globalization, food still retains unique characteristics tied to place.

Housing: Log cabins to the suburban ranch house

For most of human history, housing was built by local residents with local materials and in relation to cultural habits and climatic conditions. The Mongolian yurt, historically and today, is made of animal skins and woolen felt from locally raised animals. It is windowless, protecting its inhabitants from brutal winter winds in Central Asia, and can be easily disassembled and moved in synch with nomadic lifestyles. Likewise, the traditional frontier log cabin once suited the needs of small farmers in the woodlands of the United States.

But folk housing typically changes as spatial interaction increases and communities become less isolated over time. In the United States, from the time of early colonization up until about 1760, housing was largely folk in nature, where Old World forms and techniques dominated construction and were tied to specific ethnic immigrant groups. One common type of folk house during this time was the I-house (figure 10.7). This type of house, which was symbolic of economic attainment at the time, consisted of at least two side-by-side rooms in two stories, with gables on the side (triangular shaped rooflines).

With time, however, new ideas worked their way into old designs, creating new regional styles. In the Mid-Atlantic region, the I-house style evolved into the Georgian style (figure 10.8). This regional folk housing type usually had a gabled roof as well but typically included four rooms per floor, separated by a central hall. It is often distinguished by two window openings per floor on the end of the house and five (including the door) on the front. This style, as with the I-house, represented economic success during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Figure 10.7.An I-house made of logs. This type of folk housing is among the most widely distributed in the United States. Photo by David Ross. Stock photo ID: 1569030. Shutterstock.

Figure 10.8.Georgian style house in Newport, Rhode Island. Typical of this type of housing is a façade with five openings for windows and doors on each floor. Photo by Jiawangkun. Stock photo ID: 702450331. Shutterstock.

As the United States became further developed and spatially integrated, first with the construction of the intercontinental railways, then the national highway system, and ultimately the interstate freeway system, regional influences further eroded, and what can be referred to as popular housing styles gained prominence.

The epitome of popular housing in the United States can be seen in the ubiquitous suburban ranch house, which became the most popular form of American housing by the 1950s (figure 10.9). In contrast to folk housing, the ranch house represented the modern industrial economy. It was made almost entirely of mass-produced rather than locally produced materials. Construction was done at an industrial scale, with hundreds and even thousands of nearly identical homes built in subdivisions at the same time. Its design was the same regardless of the region in which it was built, consisting of a single-story, rectangular form with stark, minimalist interiors. The lot it was built on was flattened and scraped clean of natural vegetation, which was replaced with green lawns and shrubbery. Some allowance was made for exterior variation, such as Spanish, Tutor, or colonial style, but the overall shape and function varied very little.

Figure 10.9.Suburban ranch house. This form of popular housing is found in regions across the United States. Photo by rSnapshotPhotos. Stock photo ID: 172812272. Shutterstock.

The ranch house also reflected the modern automobile age. It was built outside of the city center in new suburban locations where modern life centered on the car. Architecturally, this was represented by a large, visually dominant garage on the front of the house. Never before had a mode of transportation played such a prominent role in residential architecture.

As with the I-house and the Georgian house of previous centuries, the ranch house represented economic achievement. The difference is that by the mid-twentieth century, a large segment of the US population could now attain this level of material success. It allowed for ownership of a single-family home in a relatively natural setting, a valued tradition in American life. The ranch house in an automobile-oriented suburban neighborhood represented the individualism and freedom of American culture.

Go to ArcGIS Online to complete exercise 10.1: “Popular music trends: Which songs top charts around the world?” and exercise 10.2: “Food and drink: How healthy is your town?”

Language

Language is arguably the most important component of human culture. It is how people interact, for instance, sharing elements of culture such as musical styles, ways of producing and preparing food, and techniques for building homes. Those who speak a common language can more easily conduct commerce, worship together, organize politically, and form families and communities. Ties based on this interaction mean that language often serves as a key component of people’s identities, guiding whom they consider to be or not to be part of their group. Without a common language, interaction is inhibited, making commerce and social interaction more difficult, often fomenting cultural divisions between people.

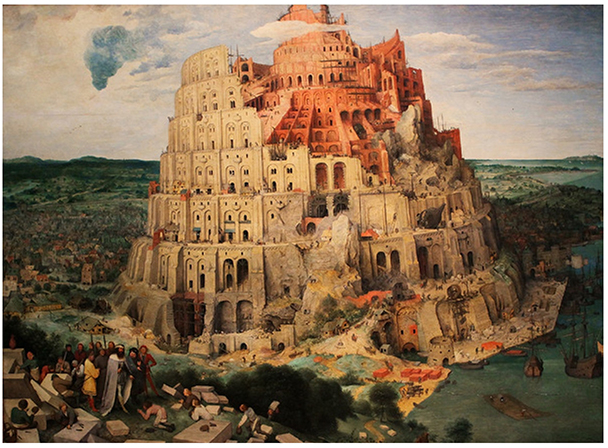

Most cultures have language-origin myths that attempt to explain why people from different places often speak in different tongues. The Judeo-Christian Bible tells the story of the Tower of Babel in ancient Mesopotamia, where God imposed multiple unintelligible languages upon those building the tower and scattered them across the land (figure 10.10). The aborigines of Australia have a different myth. They say that long ago there was an ill-tempered old woman who would scatter the fires that warmed those who were sleeping. When she died, the people celebrated, with many coming from afar to express their joy. They began to eat her flesh, and as each group consumed her, they began speaking in distinct languages. Myriad other societies have their own language-origin stories, but their commonality is that people from different places speak different languages.

Figure 10.10.Language origin myths: The Tower of Babel as painted by Pieter Brueghel in 1563. In the Judeo-Christian Bible, God is said to have imposed multiple unintelligible languages upon those building the tower, and scattered them across the land. Image by Jorisvo. Royalty-free stock photo ID: 88154914. Shutterstock.com.

Over time, linguists have developed new ideas as to why we speak different languages. It is now understood that languages evolve over time, diversifying as new words and pronunciation are added, others are dropped, and syncretic blending occurs as societies migrate and interact. In a globalized world, languages continue to change. Demographic and economic strength is making some languages more prevalent, while weakness in these areas is leading to the extinction of others.

Number of languages and speakers

Schools in the United States often offer classes in a handful of languages. Spanish, French, German, and Italian have been some common staples, with Chinese and Arabic added more recently. Occasionally, a less-common language will be taught, such as Korean, Vietnamese, or Farsi, but for the most part, students can choose from a half dozen or fewer.

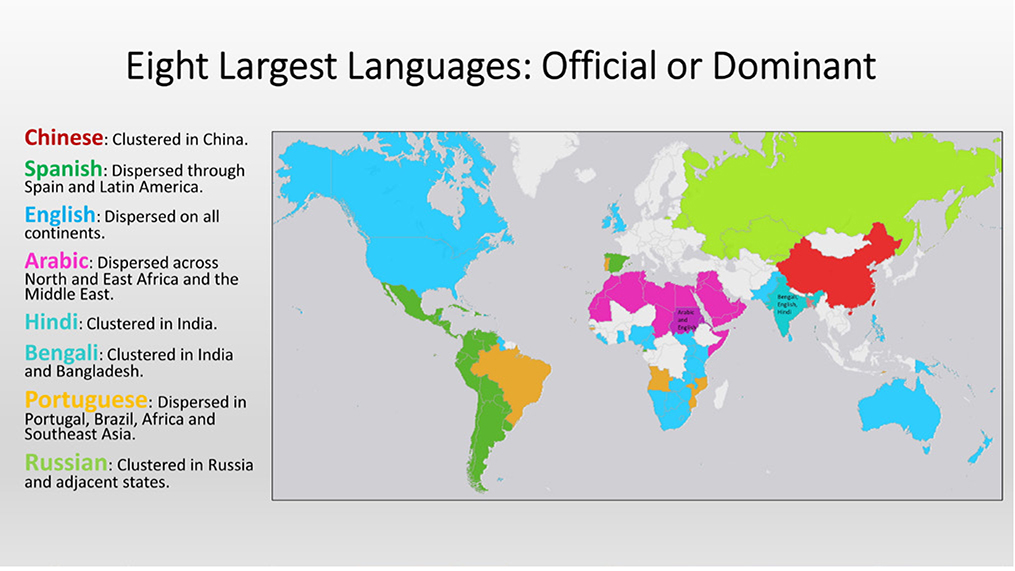

Given the limited number of foreign languages offered in schools, it may be a surprise to know that there are about 7,100 living languages in the world today. But with that said, only a handful are spoken as first languages by the vast majority of the world’s population. Over 40 percent of people speak one of just eight languages: Chinese, Spanish, English, Arabic, Hindi, Bengali, Portuguese, and Russian. Adding in another eighty-two languages incorporates over 80 percent of all people. That leaves roughly 20 percent of the world’s population speaking the remaining 7,000 or so languages. What this tells us is that a few dominant languages are used by many people over frequently large areas, and thousands of smaller languages are spoken by very few people in small, isolated areas.

Figure 10.11.Eight largest languages: Official or dominant. Explore this map at https://arcg.is/aaa50. Data source: CIA, The World Factbook.

Of the eight largest languages, spatial distributions vary. Figure 10.11 shows the countries where each is either officially recognized by the government or is the dominant language spoken by the population. Chinese, the single largest language in terms of native speakers, is spatially concentrated in China. The same can be said for Bengali and Hindi, which cluster in and around densely populated India and Bangladesh, and Russian, which is found in Russia and a handful of adjacent states. Arabic is more broadly distributed, stretching across North Africa into East Africa and the Middle East. The three European-origin languages, Spanish, English, and Portuguese, have wider distributions, the result of European colonial influence that began in the fifteenth century. English is the most widespread, dominating or being officially recognized in all the populated continents. Spanish, too, is relatively widespread, although predominately in Latin America. Portuguese is found in several regions, although in many fewer countries: Portugal in Europe, Brazil in Latin America, Angola and Mozambique in Africa, and East Timor in Southeast Asia.

Language families and their spatial distributions

Despite ancient language-origin myths, we now know that language diversity is analogous to diversity in plant and animal life. Just as life on earth originated with single-cell organisms that evolved over hundreds of millions of years into the plant and animal species we see today, languages go through their own sort of evolution. Linguists generally believe that human language evolved from an initial human proto-language many thousands of years ago. As the human population grew and spread over larger parts of the planet, this initial language went through a process of divergence. This occurs when human populations migrate and separate, losing all or most contact with groups in other locations. Although they once spoke a similar language, over time new words and pronunciations gain traction in one population group while different ones take hold in another.

You can see this process at work in our own lives. Just think about slang words you use with your friends that are not used in other parts of the country or that older generations do not understand. Now imagine that there was no interaction with people outside of your local geographic area—no travel, no phones, no TV, no internet. As your group adds new words over time, people in other places are adding their own. In the absence of spatial interaction, more and more distinct words and pronunciations will be added separately in each isolated group. Fast-forward several hundred years, and there is a good chance that there will be so many changes in vocabulary and pronunciation that it will be difficult or impossible for people in one group to communicate with people from another.

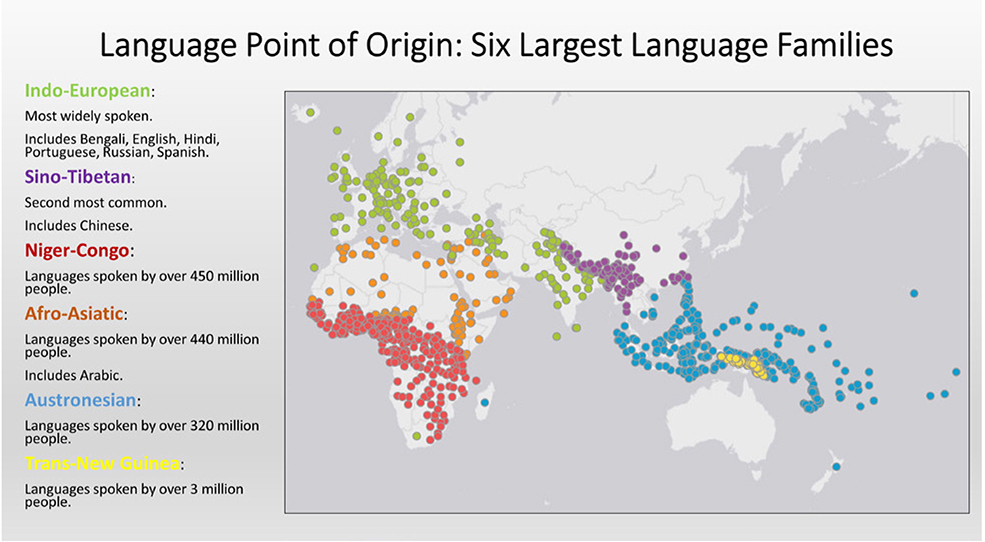

Evolutionary changes of this sort have led to the formation of language families, groups of languages that evolve from a common linguistic ancestor. Families further evolve into subfamilies and finally individual languages. There are over 140 language families, but just six of them constitute languages spoken by 85 percent of the world’s population (figure 10.12). The family with the most speakers is Indo-European, which includes six of the top eight most commonly spoken languages. Bengali, English, Hindi, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish are all part of this family, gaining numerical strength from large population clusters in South Asia and European colonial expansion. The other language families that include the top eight spoken languages are Sino-Tibetan, with Chinese, and Afro-Asiatic, which includes Arabic. The Niger-Congo and Austronesian language families are less dominant in terms of speakers, but they represent the most linguistically diverse parts of the world, each consisting of over a thousand separate languages. The smallest of the large language families is Trans-New Guinea, clustered on the island of New Guinea.

The Indo-European language family

The largest language family—and that which includes English—is Indo-European. While there is still some uncertainty, it appears that the Indo-European family developed around 4000 BCE in the area of the Black and Caspian Seas, possibly around modern-day Turkey. From there, people expanded westward through Europe and eastward into parts of Central and South Asia.

As groups of people scattered across this wide swath of territory, limited spatial interaction between them resulted in divergence into smaller language subfamilies, which then diverged into many more individual languages (figure 10.13). For this reason, it is no coincidence that the word for mother has many similarities in Dutch (moeder), Spanish (madre), and Russian (mat).

The far eastern branch of Indo-European consists of the Indic languages. These include two of the most commonly spoken languages, Bengali and Hindi, in South Asia. A bit closer to the family’s point of origin is the Iranian branch, which includes Persian and Kurdish, among others, while Eastern Europe and Russia contain the Slavic languages, such as Russian, Polish, and Czech.

Figure 10.12.Point of origin for languages: Six largest language families. Explore this map at https://arcg.is/1nSvyr. Data source: Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) 2013. Simons, Gary F. and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2017.

Figure 10.13.Indo-European language family. Sample of languages. Data source: Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) 2013.

Among the most geographically widespread languages are some from the Romance and Germanic branches. The Romance languages evolved from Latin, the language of the Roman Empire, and therefore stretch largely along the northern Mediterranean Sea, where tongues such as Italian, French, Spanish, and Portuguese are spoken. The exceptions to this geographic pattern are Romania and Moldova, which retained their Latin roots in the eastern portion of Europe. Each of these languages evolved from Latin after the fall of the Roman Empire, which left far-flung former Roman provinces relatively isolated as Europe entered the Middle Ages. Given that Romance languages are commonly spoken in the United States and are often taught in high schools and colleges, many students may notice commonalities between these languages. For instance, the verb “to sing” in both Spanish and Portuguese is cantar, in French is chanter, in Romanian is canta, and in Italian is cantare. Many other words, as well as grammatical structures, are similar, so that speakers of one Romance language can relatively quickly learn another.

The English language

English falls within the Germanic branch, along with several Scandinavian languages and, obviously, German. Around 750 BCE, the Germanic people spoke a common language and were concentrated around southern Scandinavia and coastal areas of the southern North Sea and Baltic Sea. With migration from this core area, the language began to diverge. By the third to sixth centuries CE, the Germanic language split into Northern, Eastern, and Western Germanic. Northern Germanic evolved into the Scandinavian languages, while Western Germanic split into the languages of English, Netherlandic, and German. Eastern Germanic evolved into Gothic, which eventually became extinct.

With the Germanic invasion of Britain in the fifth century, isolation and limited communication with continental Germanic led to linguistic divergence and the evolution of Old English. The well-known poem “Beowulf” was written in this tongue, but although considered an early form of English, it is unintelligible to the modern speaker:

Hie dygel lond

warigeað, wulfhleoþu, windige næssas, frecne fengelad,

ðær fyrgenstream

From there, English continued to evolve. In 1066, the Normans, people from the north of modern-day France, invaded and occupied Britain. Especially among the aristocracy, the language of the Norman invaders took hold. Their Latin-based language merged with Old English, adding new words and pronunciations. This evolved into Middle English, the language of Chaucer in The Canterbury Tales. While difficult for modern English speakers to understand, Middle English is at least partially recognizable:

A cook they hadde with hem for the nones

To boille the chiknes with the marybones,

And poudre-marchant tart and galyngale.

After 1400, further evolution led to an early form of Modern English, as words from French, Latin, and even Greek further worked their way into common usage. The printing press contributed to a greater diffusion and standardization of the language by way of the King James Bible and English dictionaries, among other texts. This period included the language of Shakespeare from the sixteenth century, which can be read and mostly understood by contemporary speakers of English, as seen in the Prologue to Romeo and Juliette:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

Thus, English is a Germanic language, borrowing much of its structure and grammar, but it also incorporates a substantial Latin influence. As with all languages, it continues to evolve. New words are added as technology changes—bicycle, camera, astronaut—while others are added as people migrate and communicate around the world—ninja (Japan), bagel (Yiddish), wok (Cantonese), latte (Italian).

Language variation

Dialects

English, like all languages, constantly evolves, but the spatial pattern of change varies from place to place. New words, grammar, and pronunciations gain traction in one place and lose dominance in another. Based on the concept of distance decay, a change can gain strength in the core area in which it evolved, but its use becomes increasingly less common as one moves away. This process of language evolution results in the formation of dialects, which are variations in a single language that remain mutually intelligible. They can be found at different scales, so that, for example, globally, an Australian dialect differs from an American one. Then, within a country, there can be further regional divisions, say between the US South and West. Finally, there can be local dialects, such as Boston, New York City, or Long Island.

The formation of dialects is the same as that of languages. In fact, with enough time and enough spatial isolation, dialects can eventually become unintelligible to outsiders, eventually making them distinct languages. Generally, variations in dialects are found in places settled prior to mass transportation and communication. When it was difficult to interact with people the next town over, dialects formed at a much more local scale. For this reason, dialects in Great Britain can vary from city to city, and the East Coast of the United States, being settled earlier, has a greater diversity of dialects than the West Coast.

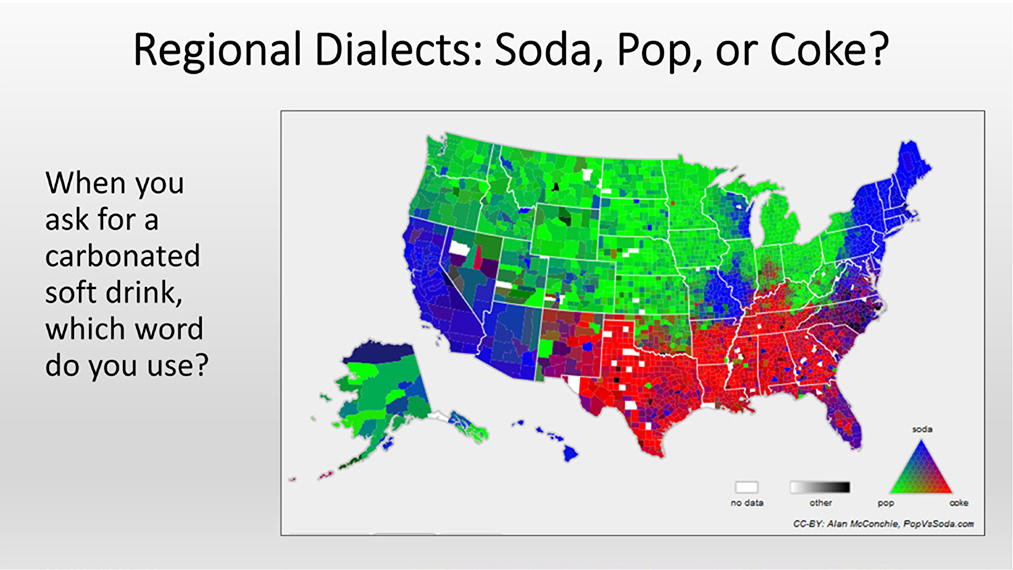

In the United States, researchers have identified various dialect districts, including Northern New England, New York City, Southern, Midland, and Western, among others. Words and pronunciations vary within these regions, so, for example, much of the South and the East Coast pronounces caramel with three syllables (“car-ra-mel”), while much of the Midwest and North Central part of the country uses two syllables (“car-ml”). Similarly, along much of the West Coast, the thing you drink water out of at school is a “drinking fountain,” while the majority of the East calls it a “water fountain.” Then there is the unusual “bubbler” used nearly exclusively in Wisconsin.

Figure 10.14 shows the commonly used “soda, pop, or Coke” example of regional dialects. This represents the generic word used for carbonated soft drinks. For example, in the South, many people ask what type of Coke a restaurant serves, even if they want something other than a cola.

In many Latino immigrant communities in the United States, and to some degree in border cities within Mexico, the Spanglish dialect is commonly used. While there is still some debate as to whether it is truly a dialect or some other language hybrid, it represents a means of communication used by millions of Latinos to varying degrees. Spanglish involves several different linguistic processes in its use. English loanwords are commonly interspersed with a Spanish sentence, so that a worker may “tomar un break” (take a break) at work or “dejar el coche en el driveway” (leave the car in the driveway). English verbs can also be converted to Spanish verbs, so to go to yard sales becomes “yardear,” and to park a car becomes “parquear.” Another common feature of Spanish is code-switching, whereby speakers randomly switch between languages in the same conversation. “When we went to the beach I saw my friend” becomes “Cuando fuimos a la playa I saw my friend.” As with all dialects, the continued use of Spanglish will depend on the degree of spatial interaction between its users and others. If immigration from Latin America continues to slow, in all likelihood Spanglish will fade away, with traditional American English dialects superseding its use. On the other hand, if steady streams of new immigrants continue to come from Latin America, Spanglish is likely to remain in use, serving as a common dialect for those with varying levels of English and Spanish competency and as a common means of communication for Latinos with different Spanish dialects from throughout the Spanish-speaking world.

Figure 10.14.Regional dialects: Soda, pop, or Coke? Image from Alan McConchie, PopVsSoda.com.

Lingua franca and global English

Language-origin myths go back millennia, signifying that incomprehension between culture groups has been of concern for most of human history. While of little importance when human societies were small and isolated, this changed once populations grew, migration flows increased, and transportation and communication technology brought people into regular contact. One common solution to mutually unintelligible languages has been to use a lingua franca, a second language used by different communities to communicate with each other. In the past, when the Roman Empire held sway over large parts of Europe and North Africa, Latin served as a lingua franca among diverse cultures. Later, with European exploration and trade, Portuguese served this purpose in many places.

British colonial expansion and economic might planted the seeds for a new global lingua franca in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. With colonies and territories across the globe, the English language gained foothold in diverse locations, used by colonial administrators in capital cities and by traders in ports that linked together an expanding global economy. After World War II, the British Empire began to fade but was replaced by an ascendant United States, which through the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century was dominant politically, militarily, and economically. This gave the English language further strength for business and political communication, establishing it as the dominant global lingua franca.

It is now estimated that one-fourth of the world’s population can communicate to some degree in English. Throughout the non-English speaking world, it is used by companies and institutions such as the European Central Bank in Germany and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations based in Indonesia. Japan-based Nissan uses English as its official corporate language, as does German-based Siemens. Many other companies across the globe either use English as an official language or require that all employees have fluency in it. In academia, it is the default language of many conferences, and universities around the world offer entire programs taught in English. Ship and airline pilots also use English as their universal language. Eighty percent of the information on the internet is in English.

But while English has become the most influential lingua franca in the world, its global usage is often distinct from that of native speakers. What is sometimes referred to as a global English, or Globish, is more common than fluency in formal standard English. This is a simplified version of the language, with a smaller vocabulary and less-rigid rules on pronunciation and grammar. The English used by airline pilots is really a simplified Airspeak, while ship pilots use Seaspeak. What is known as Special English, which consists of just 1,500 words, is used by the Voice of America in its international broadcasts. Many who use English on a daily basis for business transactions and work-related functions know just enough to get the job done; they are unlikely to be able to debate the merits of Karl Marx and Adam Smith.

Ultimately, it is unlikely that English will become a universal world language that all people speak. Rather, it will probably serve the needs of business transactions and work-related communication in a basic, simplified form. Only a small proportion of the world’s population will be truly fluent. This also leaves open the possibility that another language could gain influence over time. The position of English as a lingua franca looks relatively secure now, but Latin looked the same way during its heyday as well.

Language, identity, and assimilation

Language is often an important part of people’s identity. It acts as a social marker that expresses where someone is from geographically and often socially. A common language can tie people together by facilitating communication and a sense of community and belonging. The flip side is that different languages sometimes can keep groups of people separate, inhibiting communication and a sense of community. For this reason, there are cases of government restrictions on the use of different languages within their borders and resentment by some toward those governments for doing so. Cultural battles can occur between visions of a country that differ between those that see linguistic assimilation as essential and those who see multicultural linguistic diversity as a national strength rather than a weakness.

Examples of government suppression of language are myriad. In the 1800s, the US government prohibited the use of Native American languages in reservation and mission schools, and after World War I, many states enacted anti-German language laws. In twentieth- and twenty-first-century Turkey and Syria, the Kurdish people have seen their language banned from being used in education and politics as well as prohibited from public broadcasts. Under the dictatorship of Franco in Spain, regional languages such as Basque and Catalan were prohibited. In these and many more cases, governments were attempting to repress multiculturalism, fearing that it posed a threat to national unity. In 1992, the United Nations passed the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, which explicitly states that minority groups have the right to use their own language in private and in public. Linguistic discrimination and repression continue, however, as the declaration is nonbinding and used only as guidance by national governments.

The United States has never had an official, legally proscribed language. However, thirty-one states have enacted official English legislation. None of these laws prohibit the use of foreign languages in public or private. Rather, they typically state that all official government proceedings are to be conducted in English, although most government agencies continue to provide official state materials in additional languages as well (figure 10.15).

One reason that there is no official English policy at the national level in the United States is that, despite being a nation of immigrants, language assimilation has occurred naturally. In fact, assimilation has been so strong that the United States is sometimes called the graveyard of languages, a place where people come from around the world to lose their native tongues within a relatively short time period. Historical research shows that language assimilation by the massive waves of European immigrants from the 1920s was nearly complete by the third generation (the grandchildren of immigrants), as 95 percent of third-generation immigrants were English monolingual.

Figure 10.15.Bilingual signage. Despite official English laws in many states, government materials are often provided in multiple languages. Photo by Leonard Zhukovsky. Stock photo ID: 164333684. Shutterstock.com.

More recent immigrants continue to follow the same pattern. In Southern California, a place with large, often relatively homogenous immigrant neighborhoods, both Asian and Latino language assimilation is mostly complete by the third generation. English quickly becomes the preferred language spoken at home, with those in the second generation (US-born children of immigrants) preferring it to their parent’s native tongue. Monolingualism comes a bit later and tends to occur more quickly in Asian than in Latino groups. Most Asians can no longer speak their parent’s languages well by the second generation, but Latinos, especially Mexicans, can speak it well into the third generation.

Language diversity: Endangered languages

As human populations migrated and settled across the globe, our languages diverged into myriad tongues. Throughout history, new languages have formed, evolving from parent languages through physical separation and contact with other languages. This process continues today but with a significant difference: the rate of language extinction is accelerating rapidly. Modern transportation and communications link disparate communities like never before, encouraging the use of common languages with wider groups of people. While over 7,000 languages are spoken in the world today, it is estimated that roughly 3,000 are endangered, and there is a possibility that 50 to 90 percent of all languages could be lost in the next 100 years. Within North America, 312 languages were spoken when Europeans first arrived. Through genocide and assimilation, 40 percent of those languages have been lost, and only about twenty are currently being learned by children.

The risk factors for language extinction are small geographic ranges, being spoken by a small number of people, and a rapid decline in new speaker numbers (figure 10.16). Small populations living in clusters in the tropics, from Central America and the Amazon Basin through tropical Africa and into Southeast Asia, Northern Australia, and New Guinea, have large numbers of endangered languages. The mountainous region of the Himalayas also has a significant number of languages in danger of extinction. In North America, the native languages that remain are concentrated along the Pacific Coast, from California into Canada.

The loss of languages means a loss of culture and knowledge. Language and oral tradition are a common means of passing these on to future generations. The stories that are told, the histories of groups, the knowledge of local plants and animals for food and medicines, all pass from generation to generation orally in local languages. When these languages disappear, much of this information can be lost as well, as a more dominant language and culture supersedes it. As in the biological world, extinction implies the loss of a branch of our evolutionary history and information about how groups and places have interacted over time.

Figure 10.16.Endangered languages. Explore this map at https://arcg.is/0W1LbO. Data source: Catalogue of Endangered Languages. 2017.

Language and landscapes

Language can play a role imbuing meaning to a place, contributing to its sense of place through toponyms. Toponyms are essentially place-names, or the names that people give to features on the landscape, be it a city, mountain, river, school, street, library, or any other object commonly included on a map. Through toponyms, we can get clues as to the history of a place and the values of its residents. For instance, names such as Los Angeles and San Francisco reflect early Spanish settlement in California, while New York and New Hampshire, named after British cities, reflect settlement by people from the United Kingdom. Places with Hangman in their name can reflect a rough history in former mining boom towns, while Starvation can be found along historic migration and settlement routes. Also, places named after important historic figures illustrate who is valued in contemporary society, such as Washington, Lincoln, and other important politicians, civic leaders, artists, or generals.

But since toponyms reflect history and values, they can be controversial, often changing as new groups gain power. In Russia, Saint Petersburg was changed to Leningrad under the Soviet Union, only to be changed back to Saint Petersburg with the end of communism. In the colonized regions of Africa and Asia, many colonial names were replaced with local ones, so that Bombay became Mumbai in India and British Honduras became Belize. In Iraq, place-names went from those of the early-twentieth-century monarchy to those of the revolutionary Baath Party, then to many named after Saddam Hussein and, finally, to the removal of all signs of the fallen strongman.

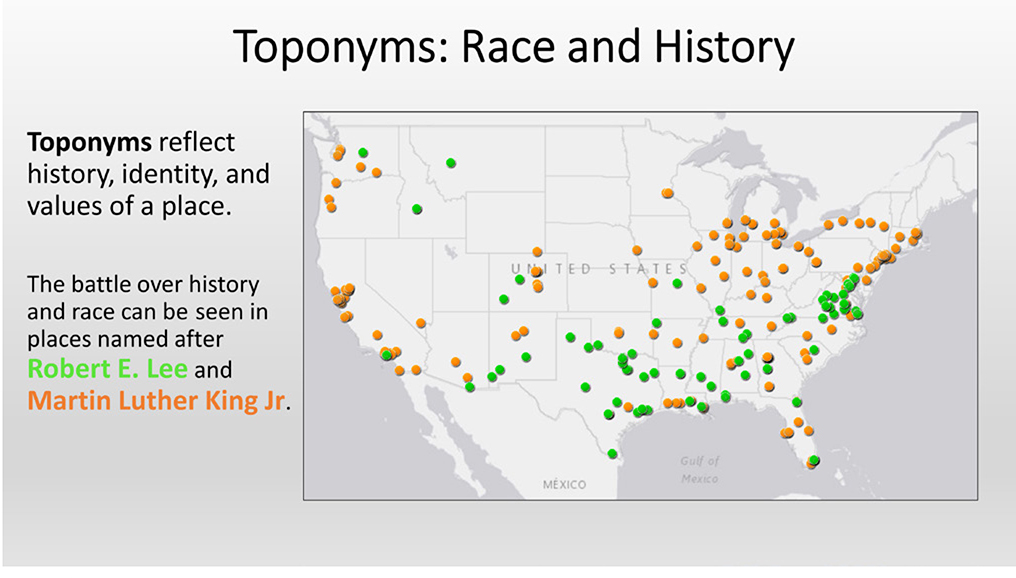

Controversy is found in the United States as well, often driven by themes of race and ethnicity (figure 10.17). Over the years, many offensive names that include derogatory terms for African Americans, Jews, Native Americans, and others have been changed. Recently, controversy over Confederate place-names have grown, with many people saying it is offensive to commemorate Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and other leaders who defended or participated in slavery. Instead, many say it is more just to commemorate those who struggled against slavery and discrimination and that parks, schools, libraries, and other places should reflect modern concepts of racial equality rather than historic oppression.

Figure 10.17.Toponyms: Race and history. Data source: US Board on Geographic Names.

Go to ArcGIS Online and complete exercise 10.3: “Language assimilation of Asians and Latinos,” and exercise 10.4: “Toponyms and sense of place.”

Religion

Along with language, religion is one of the most salient and significant elements of a culture. It forms a central part of many people’s identity and can facilitate social cohesion within groups. It shapes how people view the world and afterworld and guides behavior. It can shape how people dress, what they eat, architectural styles, marriage and sex, and myriad other aspects of culture. In fact, religion is so universally tied to human culture that no society has been found that lacks some form of religious beliefs.

Geographers typically categorize religion as universalizing or ethnic. Ethnic religions are particular to a group of people, such as a tribal or ethnic group. They tend to form organically within a community and are not tied to a specific spiritual founder. Given that they are part of a specific cultural group, ethnic religions do not proselytize, or actively seeking new members from other groups. Rather, membership in an ethnic religion usually comes from being part of the ethnic group. Universalizing religions aspire to be accepted by all. They have a founder who played a key role in the origin and diffusion of the religion, and members actively proselytize to win over new adherents.

Spatial distributions and change over time

Distribution of universalizing and ethnic religions

Of the major world religions, only Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam are universalizing, whereby anyone from any background can join the faith. As would be expected, these religions have expanded widely across the globe, dominating the religious landscape in terms of geographic coverage and number of adherents (figure 10.18 and table 10.1). Today, nearly 62 percent of the world’s population belongs to one of these three universalizing religions.

Buddhism, founded roughly 2,500 years ago, is the oldest of the universalizing religions. It began in northern India, founded by Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. Through trade and missionary activity, Buddhism spread through Southeast and East Asia, reaching northward through Nepal and China to Mongolia, east to Japan, as well as south into India, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia.

Founded in the first century CE, Christianity began in the region of modern-day Israel with the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. Missionaries spread Christianity through the region, but it expanded more widely when it became the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. From there it spread throughout Europe. As the religion of Europe, Christianity diffused globally through colonial conquest, as missionaries and migrants spread it through the Americas, into Africa, and around Pacific states such as Australia, New Zealand, and other smaller islands.

Figure 10.18.Dominant religion. Data source: The Association of Religion Data Archives.

Table 10.1.Size of major religious groups, 2010. Data source: Pew Research Center, 2015.

In the seventh century CE, Islam formed from the teachings of Muhammad in the area around Mecca and Medina in modern-day Saudi Arabia (figure 10.19). It spread across North Africa into Spain, through the Middle East, and into parts of South and Southeast Asia, such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Indonesia, among others.

Of the major ethnic religions, Hinduism dominates in size, with fewer adherents than Christianity and Islam but roughly twice as many as Buddhism. Hinduism developed in the Indus Valley region around modern-day Pakistan and India in the third to second centuries BCE. It is older than Buddhism and possibly the oldest religion on earth. It spread through South and Southeast Asia with migrants and traders and now dominates India and Nepal. Other substantial Hindu populations are found around the world in places where large numbers of South Asian migrants settled. These include places such as Suriname and Guyana in South America and Mauritius in Southern Africa.

Figure 10.19.Mecca, Saudi Arabia. All Muslims are supposed to make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lifetime. Photo by Zull Must. Stock photo ID: 590946917. Shutterstock.com.

After Hinduism, animist religions are the most commonly practiced of the ethnic religions and are practiced, for example, by Native Americans in the United States, aborigines in Australia, and countless other people on all continents. Animist religions view the world as inhabited by countless spiritual beings. These beings are not all-powerful deities, as in many other religions, but rather are tied to particular things and events. There are spirits in rocks, thunder, the sun, the moon, wind, trees, birds, even childbirth, and more. In addition, witches, ghosts, and monsters can be part of the animist belief system. The spirits can be benevolent or malevolent, helping or interfering with humans in their daily lives. Spiritual leaders, such as shamans, interact with the spirits, helping to bring good fortune or to pacify an angry spirit. Animist beliefs can be the dominant religion in some societies, while others blend them syncretically with other religions, be it with Christianity in Brazil or Buddhism in Vietnam and Mongolia.

Judaism is a smaller, though still significant, ethnic religion. Its origins are in the region around modern-day Israel, where Abraham, the founder of the Hebrew people, lived in the second century BCE. Various empires, from the Assyrians to the Romans and beyond, conquered the region, expelling the Jews and forcing them to emigrate to new lands. The Jewish diaspora settled throughout Europe and the Middle East and North Africa, then later immigrated to countries throughout the Americas. Today, there are nearly fourteen million Jews, of whom roughly six million live in Israel.

Future changes in religious composition

The religious composition of the world’s population depends on two key variables: population growth and conversion. Religions in high-growth regions are likely to see their numbers increase, while those in low- and negative-growth regions should see their numbers decline. Likewise, religions that gain more converts than they lose will grow, while those that lose more members will shrink.

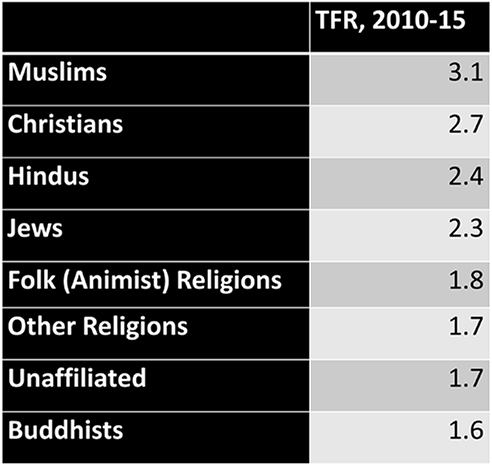

As you recall from chapter 2, the total fertility rate is a good indicator as to how fast a population is growing. Table 10.2 shows the total fertility rate by religion in recent years. Both Muslims and Christians have rates above the world average of 2.5, indicating that they are likely to constitute a greater share of followers. Buddhists and the unaffiliated (atheists, agnostics, and others) have rates well below replacement level, suggesting that their proportions will decline in coming years.

Table 10.2.Total fertility rate by religion. Data source: Pew Research Center, 2015.

The variation in total fertility rates by religion can be explained by where each is concentrated. Islam is concentrated in North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of South and Southeast Asia. These regions have relatively high fertility rates, where the transition to urban society has not yet fully taken place and where opportunities for female education and employment is often constrained. The same holds true for many Christians. While low-fertility Europe and North America are Christian, high-fertility sub-Saharan Africa also has large Christian populations. South Asia, with its large Hindu population, also has high fertility rates, contributing to the likely growth of that religion. Then there are Buddhism and the unaffiliated. Buddhists are concentrated in East Asia, such as in China and Japan, where fertility rates are very low. Likewise, the unaffiliated, such as atheists (those who do not believe in a god) and agnostics (those who say it is impossible to know if there is a god), are found primarily in low-fertility regions such as North America, Europe, China, and Japan.

Conversion rates are difficult to predict, but based on past trends, some believe that Christians, Buddhists, and Jews will see a net loss of adherents in coming decades, while the unaffiliated, Muslims, and folk/animist religions will see a net gain.

Between population growth and conversions, the Muslim population is likely to grow the most by 2050, reaching a proportion similar to that of Christians (figure 10.20). These two religions will continue to be the most popular, constituting roughly 60 percent of the world’s population between them. The proportion of unaffiliated will decline significantly, given that many in this group reside in low-growth regions such as North America, Europe, and East Asia. Buddhists and folk (animist) religions will decline proportionately as well, but to a lesser degree, while the other major religions will roughly maintain their share.

Figure 10.20.Projected change in religion: Percentage of global population. Data source: Pew Research Center, 2015.

Religion in the United States

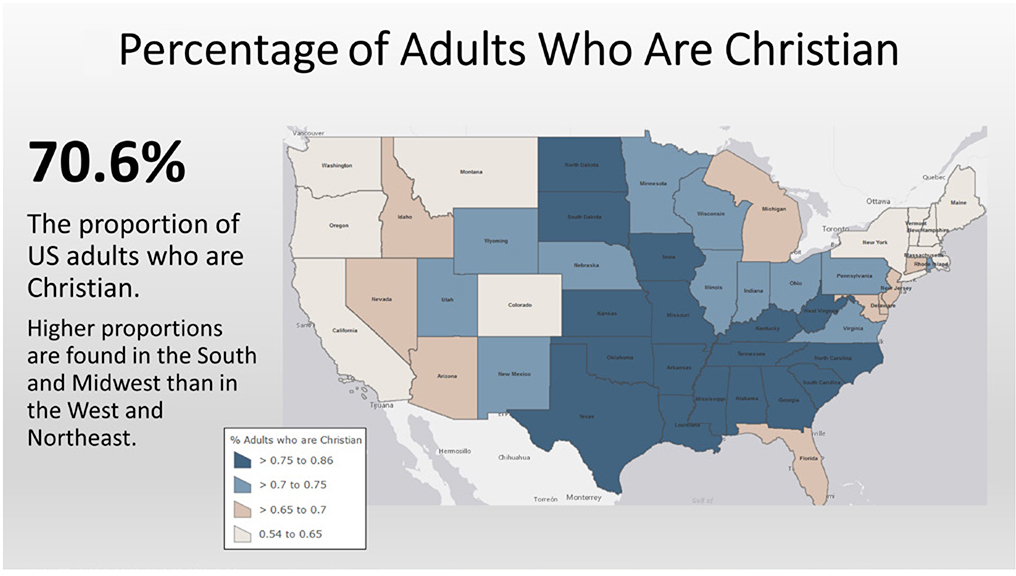

With settlement by European colonial powers, the United States formed as a Christian country, and to this day Christianity is the dominant faith. In 2014, 70.6 percent of the population identified as Christian, although that was down from 78.4 percent in 2007. Regionally, the South and Midwest are more Christian, while the West and Northeast are less so (figure 10.21). Non-Christian faiths make up 5.9 percent of the US population, with Jews being the most prominent, followed by Muslims, then Buddhists, then Hindus.

Beyond the population that identifies with a specific faith, the largest and most rapidly growing segment of the population are those who identify as unaffiliated. In 2014, 22.8 percent of the US population was unaffiliated with any specific religion. This included about 7 percent who were atheist or agnostic, but the largest group (15.8 percent) simply identified with “nothing in particular.” The unaffiliated are found especially among the younger generations, indicating that organized religion may be losing its appeal with time. Nevertheless, Americans remain religious overall. Regardless of the faith people identify with (or do not), nearly 90 percent still report that they believe in God, a number much higher than in other advanced industrial countries.

Figure 10.21.Percentage of adults who are Christian, 2014. Data source: Pew Research Center, Religion and Public Life.

Religious intolerance: Government and social restrictions on religion

Freedom to worship as one pleases is often taken for granted in the United States, where the right is protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution. However, that freedom is not universal, as various degrees of government preferences and restrictions influence which religions can or cannot be followed within their borders. At the same time, society can informally influence participation in religion. Regardless of government policies, some countries have social environments where people tolerate religious differences, while in others, people do not.

Figure 10.22 maps countries by level of government regulation of religion in 2011. Some allow nearly unrestricted freedom of religion, while others have high levels of restrictions. Australia, for instance, protects religious freedom in its constitution. The same is true in other countries, such as Argentina and Norway. However, both Argentina and Norway give some preference to one religion, with the Catholic church receiving various types of subsidies in Argentina and the state paying the salaries of Church of Norway employees.

Moving up one category toward less religious freedom, countries such as France and Nigeria stand out. France in recent years has enacted laws to prohibit the use of face coverings, such as the Islamic niqab, in public places and has banned conspicuous religious symbols, such as headscarves and Sikh turbans, in public schools. In Nigeria, freedom of religion is protected in the constitution, but several northern states have implemented Islamic-based Sharia law, using it to convict clerics and others of blasphemy for allegedly insulting the Islamic religion.

Figure 10.22.Government regulation of religion. Data source: Harris et al. 2011. Association of Religion Data Archives.

India and Iraq represent countries with medium levels of government restrictions. Religious freedom is protected in theory in India, but several states have anti-conversion laws that prevent people from changing religion. There are also numerous cases in which the government failed to protect people from religious persecution. For instance, “cow protection” groups of Hindus, for which the cow is sacred, have attacked Muslims and others accused of selling beef with impunity. In Iraq, Islam is the official religion, but the constitution guarantees freedom for Christians and a handful of other smaller religions. The country is dominated by the Shia branch of Islam, and the government regularly persecutes members of the Sunni Islam minority, using “religious profiling” in searches and arrests and discriminating against them in employment.

The greatest levels of government restriction on religion are concentrated in two areas: communist and former communist countries and countries of the Middle East and North Africa. The communist countries of Cuba, China, Vietnam, and North Korea, as well as several ex-Soviet republics, are actively hostile to all religion. In these places, religion is discouraged, although not necessarily banned. Religious leaders are often the targets of government surveillance, and proselytizing can be severely restricted. North Korea stands out as the worst in this group, essentially banning religious activity. Those accused of praying, singing hymns, or reading the Bible have been imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Even family members of those accused of being Christian have been imprisoned regardless of their personal beliefs. Anti-religious activity of the North Korean state may even take place beyond its borders; in 2016, a Christian pastor operating in China near the North Korean border was allegedly assassinated by North Korean agents.

Much of the Middle East and North Africa has high levels of government restriction on religion. Islam is the official religion of most states, enjoying a strong preference over other religions. It is often supported financially, with mosques and clerics receiving funds from the state. Non-Islamic religions, on the other hand, can face myriad restrictions, from outright bans to limits on construction of places of worship. Legal systems are often based on Sharia, or Islamic law, which holds that church and state are essentially one and the same.

Saudi Arabia stands out as one of the most religiously restrictive countries in the world. Its constitution is based on the Quran (Islamic holy text) and Sunna (teachings of Muhammad), and all non-Muslim religion is banned. Because it is a Sunni Islam state, in Saudi Arabia, even the Shia branch is persecuted, with discrimination against Shia Muslims in terms of education, employment, and more. It is illegal to violate Islamic law or insult Islam, and punishments include lashings, imprisonment, and in some cases, execution. Punishments have been imposed for posts on social media that promote atheism, witchcraft, sorcery, and other violations of Sharia law. Foreign workers are not exempt from strict religious laws. For instance, Lebanese Christians working in Saudi Arabia have been arrested and expelled for privately holding religious celebrations. The government of Saudi Arabia also promotes religious intolerance outside of its borders through active funding of ultraconservative and puritanical Wahhab Sunni teachings. By funding Wahhabist mosque construction and paying clerics’ salaries in countries around the world, Saudi Arabia has spread its influence to places with traditions of tolerant and open Islam. In African states such as Mali and Niger, and in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia, many Muslims are shedding their traditional regional versions of Islam and replacing them with Saudi Arabia’s conservative theology.

Iran stands out as another of the most religiously restrictive countries in the world. The Shia branch of Islam is its official religion, and its constitution stipulates that all laws must be based on Islamic criteria and official interpretation of sharia. While Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians are recognized as official religious minorities with the right to worship, their activities are severely restricted. Building permits for construction of places of worship by these religions are regularly denied, and there is discrimination in education and employment. The government frequently uses anti-Semitic rhetoric in official statements and promotes Holocaust denial. Proselytizing to convert Muslims to another religion, even those that are officially recognized, is strictly prohibited and even punishable by death. It is illegal for Muslims to renounce their faith or convert to another, and as a means of enforcement, identity checks are made at Christian worship services to find Muslim converts. Even Muslims who do not convert or renounce their faith are subject to punishment for violating the government’s strict interpretation of religion. The minority of Iranian Muslims who practice Sunni Islam face raids and destruction of their places of worship as well as arbitrary arrests and physical abuse by security services. Muslims who do not fast as required during the holy month of Ramadan are subject to flogging. Even more severe is punishment for insulting Islam or the prophet Mohamed, which is punishable by death.

While government action or inaction can lead to religious intolerance, social intolerance can also come from individuals, organizations, and groups. Within Europe, intolerance has grown less from state action than from the people. Religious buildings such as Jewish synagogues and Islamic mosques have been vandalized, and assaults based on religion of the victim have increased. Organized marches by hate groups have been held, some by neo-Nazi groups rallying against Jews but also, increasingly, by those opposed to the rising number of Muslim immigrants on the continent.

Intolerance can come from all faiths. Hindu nationalists in India have led hundreds of attacks against Muslims and Christians. Cow protection groups have raped and killed Muslims accused of transporting or selling beef, while Christian priests and missionaries have been attacked and beaten by Hindu mobs (figure 10.23). Buddhists in Myanmar have protested and encouraged violence against the Muslim Rohingya minority, preventing them from buying land in Buddhist villages and discouraging business and social interaction between the two groups. In Israel, ultra-Orthodox Jews have spat on other Jews, protested a Christian church choir at a mall, and discouraged ultra-Orthodox women from dating non-Jewish men.

Figure 10.23.Holy cows. Cow details at the Kapaleeswarar temple, Chennai, India. Cows are considered holy in the Hindu faith. Some militant Hindus attack those from other religions whom they accuse of selling beef. Photo by Katarina S. Stock photo ID: 261666224. Shutterstock.com.

Religiously motivated terrorism has killed and displaced millions of people across the globe. In countries such as Pakistan, Syria, and Iraq, Islamic State and other terrorist organizations have targeted Shia Muslims, Christians, and other religious faiths, killing them, forcing them to convert, or expelling them from homelands. Bombings at churches and mosques have been common, as have attacks on festivals, funerals, and minority neighborhoods.

References

Amano, Tatsuya, Brody Sandel, Heidi Eager, Edouard Bulteau, Jens-Christian Svenning, Bo Dalsgaard, Carsten Rahbek, Richard G. Davies, and William J. Sutherland. 2014. “Global Distribution and Drivers of Language Extinction Risk.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, September 3, 2014. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1574.

Ardila, A. 2005. “Spanglish: An Anglicized Spanish Dialect.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 27, no 1: 60–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986304272358.

Ash, A. 2017. “Animal Spirits.” 1843 Magazine, August/September. https://www.1843magazine.com/features/animal-spirits.

Borzykowski, B. 2017. “The International Companies Using Only English.” Capital, March 20, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/capital/story/20170317-the-international-companies-using-only-english.

Catalogue of Endangered Languages. 2017. University of Hawaii at Manoa. http://www.endangeredlanguages.com.

Chang, J. 2009. “It’s a Hip-Hop World.” Foreign Policy, October 12, 2009. http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/12/its-a-hip-hop-world.

Davis, E. H., and J. T. Morgan. 2005. “Collards in North Carolina.” Southeastern Geographer 45, no. 1: 67–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.2005.0004.

Dryer, Matthew S., and Martin Haspelmath (Eds.). 2013. The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online at http://wals.info.

Fischer, D. 1989. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frayer, L. 2017. “For Catalonia’s Separatists, Language Is the Key to Identity.” NPR, September 29, 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2017/09/29/554327011/for-catalonias-separatists-language-is-the-key-to-identity.

French, K. 2015. “Geography of American Rap: Rap Diffusion and Rap Centers.” GeoJournal 82, no. 2: 259–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-015-9681-z.

Glassie, H. 1986. “Eighteenth-Century Cultural Process in Delaware Valley Fold Building.” In Upton, D., and J. M. Vlach (eds.), Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Gold, J. R., and G. Revill. 2006. “Gathering the Voices of the People? Cecil Sharp, Cultural Hybridity, and the Folk Music of Appalachia.” GeoJournal 65, no. 1−2: 55–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-006-0007-z.

Harris, J., R. Martin, S. Montminy, and R. Fink. 2011. “Cross-National Socio-Economic and Religion Data, 2011.” Association of Religion Data Archives. http://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/ECON11.asp.