DAIQUIRÌS

For rum and lime, it was love at first sip.

In the eighteenth century, British sailors drank rum and lots of it. But it turned out that they tended to drink the same amount of grog—rum, lime, and water—one of the earliest rum cocktails. Named for Vice Admiral Edward Vernon, known as Old Grog for the grogram coat he wore, the combination curbed rampant drunkenness at sea, but the citrus also acted as a preservative and importantly helped prevent scurvy. Since then, that delicious pairing of ingredients has pleased mariners and landlubbers alike. By the end of the nineteenth century, Bacardí had pioneered his new style of rum, and then, several decades later, Prohibition pushed American cocktail culture offshore, enshrining it in Cuba.

In its most basic form, the daiquirí contains rum, lime, and a sweetener. The word itself comes from the native Taíno people and the name of a town on the southeast coast of the country near Santiago de Cuba, a perfect place to sip this delicious drink. If you can’t make it to Cuba, make sure to drink one on July 19, which is National Daiquirí Day.

EL FLORIDITA NO. 1

The Classic Daiquirí

The bar that the world knows now as El Floridita opened in 1819 as La Piña de Plata, the Silver Pineapple, originally selling fresh juice. Beverage sales boomed, a bar and restaurant joined the ranks, and in time La Piña de Plata became Bar La Florida and then El Floridita, which means “little flowery one.” Under the ownership of Constantino Ribalaigua i Vert and the game-changing patronage of Ernest Hemingway, La Florida earned its reputation as la cuna del daiquirí—literally “the cradle of the daiquirí,” but in better English, the birthplace of the legendary cocktail.

COUPE

2 OUNCES WHITE RUM

¾ OUNCE LUXARDO MARASCHINO

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

LIME OR BRANDIED CHERRY FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with a lime wheel or cherry.

EL FLORIDITA NO. 2

This variation emphasizes the citrus components of the drink.

COUPE

2 OUNCES WHITE RUM

¾ OUNCE CURAÇAO

½ OUNCE LIME JUICE

½ OUNCE ORANGE JUICE

BRANDIED CHERRY FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with a cherry.

LA CUNA DEL DAIQUIRÌ

“And now, Messieurs et Mesdames, the one and only tropical daiquirí.”

—CHARLES H. BAKER JR.,

THE GENTLEMAN’S COMPANION (1939)

Pinning down the history of a cocktail presents a mix of problems—the most pertinent being inebriation. Palates change, products disappear, and myths emerge into the collective consciousness. Somewhere in that mix lie the few true strands of a cocktail’s origin story. The daiquirí is one of the few sours with its own identity, but that identity has several variations.

Many cocktail historians point to Jennings Cox—an American mining engineer assigned to a post near Daiquirí, Cuba—as the creator of the drink. But how did Cox make it? In a letter to the editor of El País, Francesco Dominico Pagliuchi, one of Cox’s friends, recalled the cocktail’s creation as a shaken combination of Bacardi rum, lemon, sugar, and ice—lacking the quintessential lime—that arose from necessity when, in 1898, no other ingredients were available.

A second story, from Facundo Bacardí himself, traces Jennings Cox and the creation of the daiquirí to the Venus Bar in Santiago de Cuba. The Venus Bar recipe calls for Bacardi rum, lime, sugar, and ice. But this time the ingredients are stirred over shaved ice and not strained before serving. The lemon has given way to lime, but now the drink is being stirred. Competing stories muddle history yet again.

It’s hard to say which recipe was the original, but over time those changing palates, products, and myths have given us the drink we know and love today, and we do know that the daiquirí made its move from local favorite in Santiago de Cuba to Havana mainstay by way of Emilio “Maragato” Gonzalez, who first popularized the drink at the bar of the Hotel Plaza.

EL FLORIDITA NO. 3

The Hemingway Daiquirí

In the 1930s, Hemingway lived for a time in the Hotel Ambos Mundos on Havana’s Calle Obispo before buying the Finca Vigía, a fifteen-acre estate about ten miles south of Old Havana. But he spent much of his time at Bar La Florida, as it was still known then. The story goes that he wanted a daiquirí with no sugar and twice the rum. Not all of us can drink like Papa, so this recipe skips the extra hard stuff. This cocktail appeared in the Bar La Florida Cocktails guide, published in 1935, which called the drink the “E. Henmiway” Special. The bitterness of the grapefruit nicely cuts the sweetness of the rum.

COUPE

1½ OUNCES WHITE RUM

¾ OUNCE LUXARDO MARASCHINO

1 OUNCE GRAPEFRUIT JUICE

½ OUNCE LIME JUICE

BRANDIED CHERRY FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with cherry.

“He was drinking another of the frozen Daiquirís with no sugar in it. . . . It reminded him of the sea. The frappéd part of the drink was like the wake of a ship and the clear part was the way the water looked when the bow cut it when you were in shallow water over marl bottom.”

—ERNEST HEMINGWAY, ISLANDS IN THE STREAM (1970)

PAPA DOBLE

Some of us can drink like the master of modernist prose, however. This recipe is for when you want a cocktail with bite and just a hint of sweetness.

COLLINS GLASS

3 OUNCES WHITE RUM

¼ OUNCE LUXARDO MARASCHINO

3 OUNCES GRAPEFRUIT JUICE

1 OUNCE LIME JUICE

1½ CUP CRACKED ICE

GRAPEFRUIT AND BRANDIED CHERRY FOR GARNISH

Build in blender, and blend until frothy. Garnish with grapefruit slice and cherry. If you’re feeling brave, whip shake the ingredients with the ice instead. Have one and have another, and you’ll have a story to tell.

HEMINGWAY & CUBA

In 1938, when Ernest Hemingway’s notoriety began interfering with his personal life, he left Key West and moved ninety miles south to Havana. A productive alcoholic, Hemingway completed For Whom the Bell Tolls, Across the River and into the Trees, The Old Man and the Sea, and A Moveable Feast during his time in Cuba. In time he considered himself a “Cubano sato,” a garden-variety Cuban. He regularly visited Bar La Florida, where he instructed El Constante in the creation of what became the Papa Doble (page 119), which he consumed while standing because “you can drink more that way.” Hemingway’s record was fifteen consumed in one standing. It had “no taste of alcohol and felt, as you drank them, the way downhill glacier skiing feels running through powder snow.” When El Constante wrote the Bar La Florida cocktail book, he returned the ingredients to their original proportions. Toward the end of his time in Cuba, Hemingway had become a prickly drunk plied with booze by a lackey, obsessed with his virility, and easily provoked into violent rages. His personal turmoil foretold the political unrest about to overtake the island. But for more than twenty years, Hemingway was an integral part of Cuba, and his legacy continues. Today, a whole Hemingway industry exists there. A statue of him stands in his regular spot in the corner of El Floridita, and his home outside Havana has become a museum.

EL FLORIDITA NO. 4

The Frozen Daiquirí

This slightly sweeter variation of the daiquirí uses simple syrup that balances the tartness of the lime juice and the maraschino liqueur. Maraschino is distilled from marasca cherries—which hail originally from the coast of Croatia—not to be confused with those neon red cherry monsters. Luxardo is one of the best brands of maraschino liqueur.

COUPE

2 OUNCES WHITE RUM

¼ OUNCE LUXARDO MARASCHINO

½ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

1 CUP ICE

LIME FOR GARNISH

Blend at high speed for 15 seconds, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with a lime wheel. This drink is also delicious shaken over ice, as shown here.

“My mojito in La Bodeguita, my daiquirí in El Floridita.”

—ERNEST HEMINGWAY

CANTINEROS

Narciso Sal i Parera, a Catalan immigrant, took ownership of La Piña de Plata in 1898 and changed the name to La Florida. There he showed his staff how to mix drinks by “throwing” them, a technique by which the contents of a drink are transferred from one cocktail shaker tin, held high, to the other shaker tin, held low. The benefit of this technique is aeration, which improves and lengthens the mouthfeel of the drink.

Constantino Ribalaigua i Vert was born in Barcelona and arrived in Havana as a toddler in 1900. He started making drinks at age sixteen, worked at La Florida with Sal, bought the bar in 1918, and later changed the name to its most famous incarnation: El Floridita.

As noted earlier in this chapter, Jennings Cox usually receives credit for creating the daiquirí—but that’s like saying that Columbus discovered the New World. Others had been there long before him. In many ways Ribalaigua fathered the drink. Under Ribalaigua’s stewardship, El Floridita became known as the “cradle of the daiquirí,” and Constantino became known as “El Constante” for his constant presence at the bar. He always arrived early to prepare for the new day and never left before the last of his guests departed. Ribalaigua shrewdly understood that he needed a hook to make his bar into something more than just a local watering hole. In 1925, he acquired an electric blender, and the Floridita No. 4, mixed “en frappe,” was born. Through his endless experimentation and the presence of his legendary regular Ernest Hemingway, firmly planted in the corner of the bar, Ribalaigua made the daiquirí synonymous with the golden age of Cuban cocktails.

Emilio “Maragato” Gonzalez, a contemporary of Ribalaigua, popularized Cuban cocktails with the elite clientele of the bars at Hotel Florida and Hotel Plaza. With Ribalaigua, he also cofounded the Asociación de Cantineros de Cuba in 1924, nine years before the United Kingdom Bartenders Guild (often credited, incorrectly, as the world’s first bartenders’ association).

EL FLORIDITA NO. 5

The Pink Daiquirí

In the days when Facundo Bacardí y Massó was refining his distillation recipe for Cuban rum, he gave his workers a mixture of rum, sugar, and lemon or lime. In the early twentieth century, grenadine joined the mix, and the drink became known as the Bacardi Cocktail. At the time, Bacardi was the world’s leading rum and a proprietary eponym—the term used when a brand name becomes so widespread that it can lose the legal protection of being trademarked. To avoid that fate, Bacardí took the unprecedented step of suing the Barbizon Plaza Hotel and Wivel’s Restaurant, both in New York City, for not using Bacardi rum in a Bacardi Cocktail. The New York Supreme Court ruled in Bacardí’s favor, ensuring that using the company’s name meant that no one could use another brand of rum. When the Bacardi Cocktail began to fall out of favor, Bacardí tried to rename the cocktail the Grenadine Daiquirí, but the new name never stuck.

This variation of the Floridita bears a striking resemblance to the Bacardi Cocktail but adds a matching amount of maraschino liqueur to cut the sweetness of the grenadine.

COUPE

2 OUNCES WHITE RUM

¼ OUNCE LUXARDO MARASCHINO

¼ OUNCE GRENADINE (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish optionally with a brandied cherry.

NOTE

NOTE

You don’t need to use Bacardi rum for this drink. Feel free to use any good white rum without fear of legal repercussions.

BROOKLYNITE

During the Ten Years’ War (1868–1878), freedom fighters in the Captaincy General of Cuba drank a combination of honey, aguardiente—any locally distilled liquor, literally “fire water”—and citrus. They called the mixture a Canchanchara, and during that unsuccessful struggle for independence cavalry officers often had a bottle slung from their saddles. Like the Cuba Libre but less well known outside the island nation, the Canchanchara has become synonymous with the Cuban struggle for independence. Honoring that traditional combination of citrus, honey, and rum, the Brooklynite comes from the Stork Club Bar Book by Lucius Beebe (1946).

COUPE

2 OUNCES JAMAICAN RUM

¾ OUNCE HONEY SYRUP (PAGE 11)

1 OUNCE LIME JUICE

1 DASH ANGOSTURA BITTERS

LIME FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with a lime wheel.

CIENFUEGOS SHAKE

Traditionally, a “shake” consists of a dark spirit, such as bourbon or cognac, plus lime and sugar. For this drink, a heavily aged rum serves as the spirit base, and the Bénédictine provides a sweet, honeyed note. Frenchman Alexandre Le Grande created the herbal liqueur from a closely guarded combination of botanicals in the 1860s—although for marketing purposes he claimed that monks at the Benedictine Abbey of Fécamp in Normandy had produced the mixture during the French Revolution. This is a sturdy rum cocktail for anyone who enjoys a good whiskey sour.

COUPE

6 MINT LEAVES

¾ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

2 OUNCES EL DORADO 15 YEAR OLD RUM

½ OUNCE BÉNÉDICTINE

1 OUNCE LIME JUICE

3 DASHES ANGOSTURA BITTERS

In shaker tin, muddle mint with simple syrup. Add remaining ingredients to the tin, shake with ice, and double strain into a chilled coupe.

“Cienfuegos es la ciudad que más me gusta a mí.”

—BENY MORÉ

HONEYSUCKLE

Although David Embury, a New York City tax lawyer, had “never been engaged in any of the manifold branches of the liquor business,” he had very strong opinions about cocktails. In 1948 Doubleday published his book, The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks, which advises that you can transform the Honeysuckle into the Honey Bee by using a dark rum, which adds a certain brashness—sting, if you like—to the drink.

COUPE

2 OUNCES WHITE RUM

¾ OUNCE HONEY SYRUP (PAGE 11)

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with a lime wheel.

NOTE

NOTE

This recipe represents our version of a Canchanchara, pictured here, which Ricardo at Café Madrigal served to us on the rocks in a rocks glass. Here are the Café Madrigal ingredients:

2 ounces white rum

¾ ounce honey syrup (page 11)

¾ ounce lemon juice

CAPTAIN’S BLOOD

This classic cocktail clearly demonstrates the transformative powers of bitters. Its origins remain fairly murky, however. Perhaps it has something to do with Errol Flynn, who made his Hollywood debut in a leading role as the title character in Captain Blood in 1935. Flynn first visited Havana on his honeymoon the next year. The story goes that he stranded Lili Damita, his new bride, on his yacht so she couldn’t interfere with his shenanigans in the local whorehouses. Nor was that the last of his misconduct. Soon a Havana regular, Flynn habitually threw lavish dinner parties but left the tab for his guests. Hemingway once raged: “Any picture in which Errol Flynn is the best actor is its own worst enemy.” But don’t let the actor’s bad behavior dissuade you from trying this delicious drink.

COUPE

2 OUNCES JAMAICAN RUM

¾ OUNCES SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

1 OUNCE LIME JUICE

2 DASHES ANGOSTURA BITTERS

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish optionally with a lime wheel.

MULATA DAIQUIRÍ

Originally made with Bacardi Elixir, which infused rum with plums. Bacardí trademarked that liqueur in 1927, but the company no longer makes it—not to be confused with the 2011 rum of the same name made with roasted sugarcane. When Castro nationalized Bacardi’s Cuban holdings in 1960, production of the liqueur ceased. Most cocktail historians believe that Ribalaigua created the Mulata, but Héctor Zumbado y Argueta, author of El Sexto Sentido del Barman (The Barman’s Sixth Sense), credits José Maria Vazquez with creating it at the Hotel Lincoln in the 1940s.

COUPE

1½ OUNCES EL DORADO 5 YEAR RUM

¾ OUNCE TEMPUS FUGIT CRÈME DE CACAO

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

1 BARSPOON CANE SYRUP

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe.

NOTE

NOTE

This drink is rare in America, but in Cuba it holds court among the more popular daiquirís on many cocktail menus and appears in almost all of Havana Club’s marketing materials.

CLOAK & DAGGER

The split base of this cocktail allows a dark rum—the cloak—and a light rum—the dagger—to interact and form a flavor profile entirely different from a medium body rum mixed with the same secondary ingredients.

COUPE

1 OUNCE GOSLING’S BLACK SEAL RUM

1 OUNCE RHUM BARBANCOURT 4 YEAR

¾ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

LIME FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with a lime wheel.

“Where we find rum, we find action, sometimes cruel, sometimes heroic, sometimes humorous, but always vigorous and interesting.”

—CHARLES WILLIAM TAUSSIG,

PRESIDENT OF THE AMERICAN MOLASSES COMPANY,

RUM, ROMANCE, AND REBELLION (1928)

SOURS

The sour is a big, brave, beautiful category of drinks: one part sweet, one part sour, and two parts strong. The name can sound a little misleading, though. Sourness isn’t necessarily the dominant flavor. Think of the drinks in this chapter as concentrated punches that came along after the cocktail glass overtook the punch bowl in popularity. These cocktails aim for a balance between all of their elements, which have a long, delicious history of working together.

SWEATER WEATHER

This drink—named for the weather that inspired it—is one part Hot Toddy served cold and one part Dark and Stormy. Try it during the first few weeks of spring, when there’s still a lingering winter bite in the air, or as summer gives way to fall and the nights bring a hint of the coming chill. This Cienfuegos original, created by Jessica Wholers, has been on the menu since fall 2014. Despite its name, this drink is refreshing year round.

ROCKS GLASS

1½ OUNCES EL DORADO 12 YEAR RUM

¾ OUNCE RITTENHOUSE RYE

½ OUNCE COINTREAU

½ OUNCE GINGER SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

LEMON FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into rocks glass with ice. Garnish with a lemon twist.

NOTE

NOTE

For added presentation pizzazz, stud the lemon twist with whole cloves as pictured here.

ARCO DE TRIUNFO

In Parque José Martí, you’ll find the Cienfuegos Arco de Triunfo (triumphal arch), a modest but meaningful monument that celebrates Cuba’s independence from America in 1902. This drink is a variation of the Champs Élysées, a classic cocktail from the 1930 Savoy Cocktail Book by Harry Craddock, who founded the United Kingdom Bartenders Guild several years later. For this version, rum replaces the cognac. The original Savoy recipe didn’t specify green or yellow chartreuse, but we tried it both ways and green means go.

COUPE

1½ OUNCES APPLETON V/X RUM

½ OUNCE GREEN CHARTREUSE

½ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

2 DASHES ANGOSTURA BITTERS

LEMON FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish with a lemon twist.

NOTE

NOTE

The text on the triumphal arch reads:

20 DE MAYO 1902

LOS OBREROS DE CIENFUEGOS A LA REPUBLICA CUBANA

May 20, 1902

From the Workers of Cienfuegos to the Cuban Republic

PENINSULA SOUR

This rum-based ode to the New York Sour needs a full-bodied rum to provide a similar heaviness as the whiskey in the original drink and is named for the Peninsula Hotel on 55th and Fifth. But this elegant and frothy concoction also pays tribute to La Punta, the small peninsula of Cienfuegos that juts out into the surrounding bay.

ROCKS GLASS

2 OUNCES BRUGAL EXTRA VIEJO RUM

¾ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

1 EGG WHITE

FRUITY RED WINE, PREFERABLY PINOT NOIR

Dry shake all ingredients except red wine to emulsify, then shake again with ice to chill and dilute. Strain into rocks glass with ice, float red wine on top, and garnish optionally with an orange and lemon twist.

NOTE

NOTE

The different densities of the parts of this drink create a nice layered effect. Make it when you want to impress.

ONE HUNDRED FIRES

Camilo Cienfuegos fought alongside Castro against Batista’s forces, and the people of Cuba loved him as much as they loved Castro—if not more so. On January 8, 1959, when Castro entered Havana, the island’s new leader announced that he was turning military barracks into a school and then asked Cienfuegos, “¿Voy bien, Camilo?” (Am I doing OK?), to which Cienfuegos replied: “Vas bien, Fidel” (You’re doing fine). Cienfuegos died in a plane crash at age twenty-seven, spurring numerous conspiracy theories about the circumstances of his death and ensuring his cultural immortality in Cuba. The hellfire bitters and the flaming chili pepper in this cocktail pay homage to the hundred fires of his name, while the sweetness of the pineapple juice tempers the heat.

ROCKS GLASS

¾ OUNCE APPLE BRANDY

¾ OUNCE SANTA TERESA 1796 RUM

½ OUNCE CHILI SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

½ OUNCE PINEAPPLE JUICE

2 DASHES HELLFIRE BITTERS

CHILI PEPPER FOR GARNISH

151 RUM FOR PRESENTATION

Whip shake all ingredients, and pour into a double rocks glass filled with crushed ice. Garnish with half a chili pepper filled with the 151, and set overproof rum on fire.

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY CLUB

Few cocktails have the honor of summing up an entire century’s worth of drinks, and the Twentieth Century isn’t one of them. The New York Central Railroad ran a train line, called the Twentieth Century Limited, back and forth across the thousand miles between Manhattan and Chicago. This variant of the drink, named for the luxury service, uses rum instead of gin—another fine example of rum’s ability to elevate a classic—while the citrus-forward Lillet Blanc enhances the tropical notes in the rich Tempus Fugit.

PUNCH GLASS

1 OUNCE RON DEL BARRILITO

¾ OUNCE LILLET BLANC

¾ OUNCE TEMPUS FUGIT CRÈME DE CACAO

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

LEMON FOR GARNISH

Shake with ice, and strain into punch glass. Garnish with a lemon wheel.

NOTE

NOTE

Tempus Fugit—which means “time flies” in Latin—sources cacao from Venezuela and vanilla from Mexico, paying deference to the original sources of the finest ingredients for crèmes de cacao found in nineteenth-century recipes.

BITTERSWEET SYMPHONY

A pear and rosemary pie served as the inspiration for this drink. When you combine pear with the savory notes of the rosemary and the sweetness of the rum, Bärenjäger, and syrup, you get this delicious sour. Bärenjäger, which means “bear hunter” in German, is a honey liqueur.

COUPE

2 SPRIGS ROSEMARY

¾ OUNCE DEMERARA SYRUP (PAGE 10)

1 OUNCE EL DORADO 12 YEAR OLD RUM

¾ OUNCE ORCHARD PEAR LIQUEUR

⅜ OUNCE BÄRENJÄGER

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

SALT FOR GARNISH

Gently muddle 1 sprig of rosemary in the syrup. Build remaining ingredients, shake with ice, and double strain into chilled coupe. Garnish with rosemary, and sprinkle with salt.

NOTE

NOTE

This cocktail pairs perfectly with the 1997 song of the same name by Britpop band The Verve.

DECEMBER MORN

This is the lovechild of a September Morn and Jack Rose, both from the Savoy Cocktail Book. The September Morn is a close relative of the better known Clover Club Cocktail, both red fruit sours. The Clover Club relies on raspberries for its pink hue and lighter flavor, while grenadine gives the September Morn its richer flavor and color. Ernest Hemingway helped popularize the Jack Rose, which also includes grenadine, by featuring it in The Sun Also Rises.

COUPE

1½ OUNCES FLOR DE CAÑA EXTRA DRY 4 YEAR RUM

½ OUNCE LAIRD’S APPLEJACK

¾ OUNCE GRENADINE (PAGE 10)

½ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

1 EGG WHITE

CINNAMON FOR GARNISH

Dry shake all ingredients without ice; then shake again with ice. Strain into chilled coupe. Grate fresh cinnamon on top.

NOTE

NOTE

The word “grenadine” comes from grenade, the French word for “pomegranate.” It doesn’t appear in any recipes in Jerry Thomas’s How to Mix Drinks (1862), but the Savoy Cocktail Book (1930) includes nearly 100 cocktails that feature it. Don’t confuse the grenadine in this cocktail with the cloying mixture of sugar water, coloring, and preservatives made by a company that also sells sweetened lime juice.

DERNIER MOT

At the Detroit Athletic Club bar, Frank Fogarty, a vaudeville performer, created what has become a timeless cocktail, the Last Word. In this Caribbean variation on that classic, the gin is replaced by a rhum agricole. The French-style rum—which gives the drink’s name its French twist—is distilled from fresh sugarcane instead of molasses, which gives the spirit its vibrant fruit and grassy notes. Each of the four ingredients in this recipe is a heavy hitter that can stand up to the rest.

COUPE

¾ OUNCE GREEN CHARTREUSE

¾ OUNCE LA FAVORITE BLANC AGRICOLE RHUM

¾ OUNCE LUXARDO MARASCHINO

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe.

PERIODISTA

Ernest Hemingway might have enjoyed this classic Cuban cocktail, whose name means “journalist” in Spanish. Journalists in Miami and Havana might have drunk it in excess during the Cuban missile crisis. It’s hard to say because it’s hard to pin down the origin story of the drink. Further complicating matters, this drink sometimes appears as a variation of the Palmetto, made with rum, vermouth, and bitters.

COUPE

¾ OUNCES APRICOT BRANDY

¾ OUNCES COINTREAU

¾ OUNCES EL DORADO 3 YEAR RUM

¾ OUNCES LEMON JUICE

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe. Garnish optionally with a lemon twist.

BERRY DANGEROUS FIX

Woodland strawberries served as the inspiration for this delicious drink. They’re small—only the size of your fingernail—but much more flavorful and floral than the traditional variety at your local grocery store. Like the strawberries that also grow in Cuba, the woodland kind are delicate and don’t travel well. But several dashes of orange flower water allow you to enjoy the taste of these berries year round.

ROCKS GLASS

3 STRAWBERRIES

½ OUNCE CANE SYRUP

1½ OUNCES PLANTATION 3 STAR WHITE RUM

¼ OUNCE CAMPARI

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

3 DASHES ORANGE FLOWER WATER

LEMON FOR GARNISH

In a shaking tin, muddle 2 of the strawberries in cane syrup; then build the rest of the ingredients. Dry shake, pour into a double rocks glass, and top with crushed ice. Garnish with the third strawberry and a lemon wheel. Serve with a straw.

SOUTHERN SMITH & CROSS

People have been gazing at the constellation Crux, commonly called the Southern Cross, for many centuries. In the time of the Roman Empire, astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy classified it as a part of the constellation Centaurus, but João Faras, astronomer to King Manuel I of Portugal, receives credit for first describing it accurately in 1500. This cocktail blends two older recipes named after the constellation, one from Williams Schmidt’s The Flowing Bowl (1891) and the other from Elsa af Trolle’s Cocktails (1927). Think of it as a darker, funkier margarita.

COUPE

1½ OUNCES SMITH & CROSS RUM

¼ OUNCE GRAND MARNIER

½ OUNCE DEMERARA SYRUP (PAGE 10)

½ OUNCE LIME JUICE

Shake with ice, and strain into a chilled coupe.

For completists, here are the ingredients lists from the older recipes:

SOUTHERN CROSS

COUPE

Flowing Bowl version

THE JUICE OF A LIME

A DASH MINERAL WATER

A SPOONFUL OF SUGAR

2⁄3 OF ST. CROIX RUM

1⁄3 OF BRANDY

1 DASH OF CURAÇAO

Cocktails version

THE JUICE OF 1 LEMON

DASH SODA WATER

A TABLESPOON OF SUGAR

2⁄3 ST. CROIX RUM (CRUZAN)

1⁄3 OF COGNAC

1 DASH OF ORANGE CURAÇAO

SWIZZLES

As refreshing as they sound, swizzles take their name from the method of preparing them. The swizzle is neither shaken nor stirred; instead, all of the ingredients are added to a glass with crushed ice and then mixed with a swizzle stick. You hold the pronged swizzle stick between your palms and roll it back and forth until a nice frost forms on the glass. The swizzle stick traditionally was made from the branches of a swizzle stick tree, Quararibea turbinate, also known as an allspice bush. It makes cocktails frothy and delicious and also comes in handy when you need to beat back anyone trying to sneak a sip of your swizzle. In lieu of a swizzle stick, you can use a barspoon.

DUTCHIE

Smith & Cross is a traditional Jamaican rum with distinct flavors that made Jamaican rum famous in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Genever is a precursor to modern gin; as such, it’s a throwback, but it’s been making a resurgence in recent years. Both of these rather old-fashioned styles of spirits have bold flavors, but they balance each other out.

WINE GLASS

¾ OUNCE BOLS GENEVER

¾ OUNCE SMITH & CROSS RUM

¾ OUNCE YELLOW CHARTREUSE

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

1 BARSPOON CANE SYRUP

½ OUNCE CLUB SODA

PEYCHAUD’S BITTERS

MINT LEAVES FOR GARNISH

Swizzle all ingredients except club soda and bitters with crushed ice in a wine glass. Top with club soda and Peychaud’s bitters to taste. Garnish with mint.

NOTE

NOTE

Smith & Cross, a bartender favorite, has a super-funky taste profile: Think bandages, burning tires, and rotting fruit—but delicious. It’s also 114 proof, so tread carefully.

CATAMARAN

The island of Curaçao lies off the coast of Venezuela in the southern Caribbean Sea. Spanish settlers found that sugarcane didn’t grow well on this desert island and instead planted Valencia orange trees. Those didn’t do well either: The sandy soil made the oranges extremely bitter. Locals called the bitter fruits larahas—a corruption of naranjas, Spanish for “oranges”—but in 1771 chemist Hieronymus Gaubius noticed the aromatic qualities of the oils from larahas peels. By this time, the Dutch had won their independence from the Spanish and began settling the island in earnest. Colonists dried the peels and preserved them in rum to ship back to Holland. There, distillers macerated them into Curaçao liqueur. The slight bitterness of Curaçao works well with the nutty orgeat and references the mai tai, a tiki classic.

ROCKS GLASS

¾ OUNCE APPLETON V/X RUM

¾ OUNCE BEEFEATER GIN

¼ OUNCE CURAÇAO

½ OUNCE ORGEAT (PAGE 11)

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

PINEAPPLE FOR GARNISH

Whip shake, and strain into a double rocks glass filled with crushed ice. Garnish with a pineapple slice.

RUBY RUM

This is Hemingway’s beloved daiquirí, reworked into a swizzle, in which Aperol—an Italian aperitif made with bitter orange, cinchona (the tree that gives us quinine), rhubarb, and other ingredients—replaces the maraschino liqueur. The grapefruit juice highlights the drink’s delicate bitterness, reined in by the full-bodied Gosling’s and herbal mint notes.

SWIZZLE GLASS

1 OUNCE APEROL

1 OUNCE GOSLING’S BLACK SEAL RUM

½ OUNCE MINT SYRUP (PAGE 11)

½ OUNCE GRAPEFRUIT JUICE

½ OUNCE LIME JUICE

MINT LEAVES FOR GARNISH

Swizzle all ingredients with crushed ice in a swizzle glass, and garnish with mint.

NOTE

NOTE

James Gosling left England in 1806, bound for America, then still a fledgling nation. He set up shop in Bermuda, however, and founded the company that still bears his name. In 1863, Gosling released its first Old Rum, distributing it in barrels to people who brought their own bottles, which were sealed in black wax, which gave the product its new name.

MIND IF I DO JULEP

Although technically not a swizzle, this drink requires a similar technique (ingredients mixed over crushed ice) and results in an equal amount of refreshment. In the 1700s the julep was predominantly a rum drink. After the Revolutionary War, it transitioned to whiskey, followed by brandy in more prosperous times. The mint remains the common factor. Later, many juleps featured the addition of a rum float—“controversial” according to the always opinionated David Embury. The Mind If I Do Julep embraces that tradition but reverses it by adding a float of Laird’s Applejack to a rum julep.

JULEP CUP

2 OUNCES BARBANCOURT 8 YEAR RUM

½ OUNCE BUFFALO TRACE BOURBON

¼ OUNCE CANE SYRUP

¼ OUNCE LAIRD’S APPLEJACK

MINT LEAVES FOR GARNISH

Swizzle all ingredients except applejack with crushed ice in a julep cup. Float applejack on top, and garnish with mint.

NOTE

NOTE

Like many alcoholic beverages, especially those featuring mint, the julep originally served as a medicinal treatment for stomach ailments.

MARTINIQUE SWIZZLE

Swizzle stick trees grow abundantly on Martinique, where swizzle sticks are called baton-lele. This cocktail is a great way to showcase a classic rum and the importance of technique. The ingredients make it seem similar to a daiquirí, but swizzling aerates and dilutes differently than shaking, so the elements taste brighter and fresher.

SWIZZLE GLASS

2 OUNCES SAINT JAMES AMBER RUM

½ OUNCE CANE SYRUP

½ OUNCE LIME JUICE

1 DASH ABSINTHE

1 DASH ANGOSTURA BITTERS

MINT LEAVES FOR GARNISH

Swizzle all ingredients with crushed ice in a swizzle glass. Garnish with mint.

“Swizzles originated in the West Indies, where everything, including hot chocolate, is swizzled. A swizzle stick is the branch of a tropical bush with three to five forked branches on the end. You insert this in the glass or pitcher and twirl the stem rapidly between the palms of your hands. By rapid swizzling with fine ice, you’ll get a good outside frost.”

—TRADER VIC’S BARTENDER’S GUIDE

ARRACK SWIZZLE

Batavia—the Roman name for part of what became the Netherlands and the Dutch colonial name for Jakarta—was the capital of the Dutch East Indies until the Japanese invaded in 1942 and renamed the city Jakarta. Arrack is a liquor made in Southeast Asia from sugarcane and fermented red rice. Batavia arrack has been made since the seventeenth century, and its powerful, funky flavor was a must in classic punch recipes. Here that power is kept in check by the Chairman’s Reserve rum.

WINE GLASS

1 OUNCE BATAVIA ARRACK

¾ OUNCE CHAIRMAN’S RESERVE RUM

¾ OUNCE COCCHI SWEET VERMOUTH

½ OUNCE CANE SYRUP

¾ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

6 DASHES ANGOSTURA BITTERS

MINT FOR GARNISH

Swizzle all ingredients except bitters with crushed ice in a wine glass. Top with bitters, and garnish with a mint sprig.

QUEEN’S PARK SWIZZLE

The Queen’s Park is a hotel on the island of Trinidad that boasted poor accommodations but a good bar, the Long Bar with the Brass Rail. The original recipe called for a dark, heavy demerara rum, probably because Trinidad wasn’t producing its own rum when this drink was created. Demerara rum came from nearby Guyana, but a lighter rum serves as a better vehicle for the flavors of the lime and bitters.

SWIZZLE GLASS

12–15 MINT LEAVES

¾ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

2 OUNCES LIGHT RUM

1 OUNCE LIME JUICE

ANGOSTURA BITTERS

PEYCHAUD’S BITTERS

MINT LEAVES FOR GARNISH

In a swizzle glass, muddle mint in the syrup. Add rum and lime juice, and swizzle with crushed ice. Top with Angostura and Peychaud’s bitters to taste, and garnish with mint.

RICKEYS & OTHER HIGHBALLS

The highball is a family of mixed drinks in which the base spirit combines with a nonalcoholic mixer, often club soda. It might seem strange to us today, but for most of the nineteenth century the idea of diluting a perfectly good spirit with club soda was crazy talk. Thankfully, tastes change. The rickey takes its name from Joe Rickey, a southern lobbyist who popularized the whiskey version in Washington, D.C., during the 1880s. But the drink gained widespread popularity about a decade later when made with gin. At that same time, bartender Patrick Gavin Duffy, who later wrote the Official Mixer’s Manual (1934), was making highballs in New York. (Using railroad terminology, the word originally referred to how fast the drink could be made.) Broadly, a rickey uses lime juice while a Collins uses lemon juice.

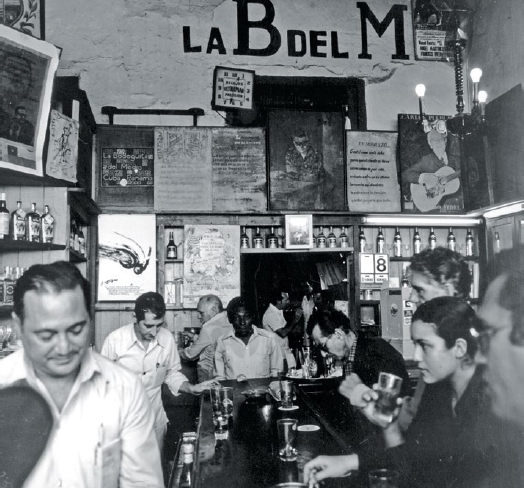

MOJITO

In 1950, Angel Martinez officially changed the name of his bodega from Casa Martinez to La Bodeguita del Medio, and by then he was already well known for his Mojito Criollo (“little Creole citrus mixture” in Spanish). The bartenders there receive credit for first muddling the mint in the drink. Whether first enjoyed off the coast of Havana aboard Sir Francis Drake’s ship (page 172) or crafted by the skillful hands of cantineros past and present, the mojito is an iconic Cuban cocktail.

COLLINS GLASS

6 MINT LEAVES, PLUS ADDITIONAL FOR GARNISH

¾ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

2 OUNCES WHITE RUM

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

CLUB SODA

In a shaker tin, muddle the mint leaves in simple syrup. Add rum and lime juice. Whip shake with crushed ice, and strain into a Collins glass filled with ice cubes. Top with club soda, and garnish with mint.

Bartenders make the drink a little differently in Cuba. Muddle 1 heaping barspoon superfine sugar, 12 mint leaves, and 1 ounce lime juice in a Collins glass. Add 2 ounces club soda, swizzle, fill with ice cubes, and top with rum.

NOTE

NOTE

If you can find it, Havana Club 3 Year Rum is best for making mojitos. See page 174 for more on Havana Club.

THE PROTO-MOJITO

The precursor to the mojito was probably the Draque, possibly created by Sir Francis Drake, his cousin Richard Drake, or his nephew Sir Richard Hawkins, perhaps to mask the unpleasant odors and flavors of aguardiente or to relieve a stomach ailment.

In 1585, Queen Elizabeth I of England signed a treaty with the Dutch, a move that her former brother-in-law, King Philip II of Spain, took as a declaration of war since the Netherlands belonged to the Spanish crown at the time. The next year, in a preemptive strike, Elizabeth sent Drake on his Great Expedition to attack Spanish colonies in the New World. (Returning the favor, King Philip purportedly put a bounty of 20,000 ducats—more than $6 million today—on Sir Francis’s head.) Drake’s fleet intended to sack Havana before returning to England, but his crew fell ill, and he abandoned the plan.

Mint has always been used as a remedy for stomach disorders, and we know that Drake’s ships sailed with aguardiente on them. Today, many of the Spanish ports that Drake hit on his Great Expedition feature drinks similar to the Draque, whether existing before he got there or arising afterward. In Maracaibo, Venezuela, a draque is an aguardiente-based stomach remedy. In Mexico, the drage is an energetic herbal tisane. In Cartagena, Colombia, it offers relief from dehydration.

The Draque began transforming into the mojito at a beach bar called La Concha in Marianao, Cuba. The Concha Mojito was basically a Ron Collins, with rum, lemon juice, sugar, Angostura bitters, and club soda. The 1935 Bar La Florida cocktail guide features a Mojito Criollo that drops the Angostura bitters and includes mint, but La Bodeguita del Medio (shown below) remains most well known for popularizing the tropical classic.

HAVANA CLUB

The Arechabala family began producing Havana Club rum in Cárdenas, Cuba, in 1878, around the same time that the Bacardí family first started distilling in Santiago de Cuba. José Arechabala y Aldama established the company, but his grandnephew, José Iturrioz y Llaguno, created the new mythical product.

Iturrioz took over the company in 1926, when Cárdenas was stalling in a severe economic depression due largely to the shallowness of its port, which redirected business to Havana and Matanzas. Iturrioz marshaled engineers, equipment, and the manpower needed to dredge the harbor and construct the Espigón (breakwater) in 1939. For four years, countless Cardenenses carried out this monumental task.

By 1944 the job was complete and Cárdenas also had a new shoreline with a new marina, seaside road, esplanade, green spaces, and a monument commemorating the first time the Cuban flag flew on Cuban soil. By the late 1950s, the Arechabala family was producing not only Havana Club rum but also Relicario brandy, Arechabala creams, Quirnal vermouth, Arechabala Cognac, Caña Rum, and candy. After the revolution, Castro’s government nationalized the distillery. The Arechabala family fled to Spain and allowed the trademark to lapse in 1973.

The Cuban government partnered with Pernod-Ricard in 1993 to produce the “original” Havana Club, which it claimed as its own. The next year Bacardi partnered with the Arechabalas and then a few years later bought the family’s residual rights to the Havana Club brand, including the original distillation recipe. The legal battle between the two spirits giants for recognition of the official trademark continues today amid the ongoing trade embargo.

SOLERA BUCK

A buck is a drink made with ginger beer. This drink is a little Dark & Stormy plus a little Moscow Mule, minus any brand affiliations. The Dark & Stormy became popular on the British island of Bermuda, made using Gosling’s dark, funky, and sweet molasses rum. After 1860, the Royal Navy began making its own ginger beer, around the time that the Dark & Stormy was invented. Originally yeast gave the ginger beverage its fizz. For this drink, the ginger appears in the form of a syrup, and club soda brings the fizz.

MUG

2 OUNCES SOLERA RUM

¾ OUNCE GINGER SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¾ OUNCE LIME JUICE

CLUB SODA

CANDIED GINGER AND LIME FOR GARNISH

Shake all ingredients except club soda with ice, and strain into a copper mug filled with ice. Top with club soda, and garnish with candied ginger and a lime wheel.

NOTE

NOTE

Gosling’s holds the trademark to the Dark & Stormy cocktail, which means, if you order the drink by that name, it must contain Gosling’s rum.

CUBA LIBRE

Rupert Grant—a calypso songwriter from the island of Trinidad better known by his nom de chanson, Lord Invader—originally penned the song “Rum and Coca-Cola” about American soldiers and their off-duty activities. The Andrews Sisters’ 1945 version of the song hit number one stateside and became so popular that it was removed from some jukeboxes to preserve the sanity of waitresses. That song brought the ingredients of the Cuba Libre to a broad audience, but the pedigree of the drink goes back much farther.

HIGHBALL GLASS

2 OUNCES WHITE RUM

5 OUNCES COCA-COLA

LIME JUICE TO TASTE

LIME FOR GARNISH

Build in a highball glass with ice, and stir a few times with a barspoon. Garnish with lime wheel.

NOTE

NOTE

Havana Club 3 Year Rum is great for making the Cuba Libre, but you can substitute Caña Brava Rum.

Turn the page for more about the history of the Cuba Libre.

POR CUBA LIBRE

Newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer used the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in February 1898 to bring the outcry to free Cuba from Spanish rule to a fever pitch. Soldiers gave a U.S. Army post in Jacksonville, Florida, the nickname “Camp Cuba Libre,” but the term had existed previously, in a different armed conflict. Freedom fighters during the Ten Years’ War often drank hot water sweetened with honey, calling it a Cuba Libre. But there’s a good chance that due to differences in translation, “hot water” meant aguardiente. But that still leaves the question of when, where, and how the cola entered the picture.

In 1887, Asa Candler purchased the formula for John Pemberton’s tonic made from coca leaves and kola nuts, known now as Coca-Cola. As peace was being negotiated tween America and Spain, Candler’s brother, Warren, a Methodist bishop, sailed for Cuba to determine what missionary work could be done there and to research opportunities for commercial ventures. After the Treaty of Paris of 1898 ended the war, a Coca-Cola wholesale outfit was established in Havana.

With Coca-Cola’s presence entrenched in Havana, the origin story holds that American soldiers at a bar in Cuba, around the time of the Spanish-American War, ordered a rum and Coca-Cola, toasting their Cuban friends: “Por Cuba libre!” From one set of freedom fighters to another, the Cuba Libre as we know it today came to pass.

THE CARIBBEAN

In this modern cocktail, the Cuba Libre gets a modern makeover. This recipe comes from Jeff Berry’s Potions of the Caribbean and before that hails from a private notebook of Bob Esmino, the bar manager of the Kon-Tiki restaurant chain in Portland, Oregon, Cleveland, and Chicago in the 1960s.

TIKI BOWL

1¼ OUNCES DARK JAMAICAN RUM

1 OUNCE GOLD PUERTO RICAN RUM

½ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

¼ OUNCE GINGER SYRUP (PAGE 10)

½ OUNCE LIME JUICE

6 DASHES PERNOD

1 DASH ANGOSTURA BITTERS

1½ OUNCES COCA-COLA

Build all ingredients except the Coca-Cola in a tiki bowl. Swizzle with crushed ice, add Coca-Cola, and swizzle a little more. Serve with a straw.

INTRO TO AWESOME

This cocktail presents our take on Audrey Saunders’s Intro to Aperol, which uses gin and, of course, Aperol—a bitter-orange aperitif—as its base. Saunders studied with and worked alongside master mixologist Dale DeGroff in the late 1990s and then opened the Pegu Club in New York City’s SoHo neighborhood in August 2005, which helped spark the craft cocktail renaissance. The Intro to Awesome substitutes a dry white rum for the gin to allow the bittersweet notes of the Aperol to shine through. Cucumber works especially well with Aperol, creating an almost watermelon-like flavor.

COLLINS GLASS

6 CUCUMBER SLICES

½ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

1½ OUNCES FLOR DE CAÑA EXTRA DRY RUM

1 OUNCE APEROL

1 OUNCE LIME JUICE

1 OUNCE CLUB SODA

SALT FOR GARNISH

In a shaking tin, muddle three cucumber slices in the simple syrup. Build the rest of the drink except club soda. Shake with ice, and double strain into a Collins glass with ice. Top with club soda, a few shakes of salt, and the three remaining cucumber slices.

ISLA TEA

Several origin stories exist for the infamous Long Island Iced Tea. One posits it as the winning entry in a 1972 cocktail competition in which the only stipulation held that the cocktail had to contain triple sec. But references to Long Island Iced Tea exist in Betty Crocker’s 1961 New Picture Cookbook. Another version holds that the concoction goes as far back as a Prohibition-era drink from Long Island, Tennessee. Either way, Long Island Iced Tea has developed a reputation as the go-to drink for getting smashed fast without tasting any of the ingredients. This modern take provides a balanced cocktail in which you can savor the interaction of the various spirits—instead of just getting bombed at a frat bar.

COLLINS GLASS

½ OUNCE COINTREAU

½ OUNCE CRUZAN BLACK STRAP RUM

½ OUNCE GIN

½ OUNCE MEZCAL

½ OUNCE PLANTATION RUM

½ OUNCE SIMPLE SYRUP (PAGE 10)

½ OUNCE LEMON JUICE

½ OUNCE LIME JUICE

10 DASHES ANGOSTURA BITTERS

1½ OUNCES COCA-COLA

Shake all ingredients except the Coca-Cola with ice. Strain into a Collins glass filled with crushed ice, and top with Coca-Cola.