THE BAR & THE COUNTRY

“All roads lead to rum.”

—W. C. Fields

CIENFUEGOS IS MANY THINGS: a hundred fires, a province, a breezy port city, a governor, a battle, a revolutionary, and a tropical gathering place in the pulsing heart of Manhattan’s East Village.

Cienfuegos, Cuba—on the southern coast, facing the Cayman Islands—was founded on April 22, 1819, as Fernandina de Jagua by French emigrants led by Louis de Clouet and named in honor of the Spanish king, Fernando VII. When the settlement became a town a decade later, the king authorized changing its name to Cienfuegos to honor José Cienfuegos y Jovellanos, captain general of the island. As the nineteenth century progressed, Cienfuegos became a vital port city, strategic for sugarcane and tobacco production. In sun-drenched streets bathed in tropical breezes, men ordered their rums by the finger, and women sipped exotic punches.

At the end of the 1800s, Cuba tried desperately to throw off the chains of centuries of Spanish rule. The three-year Cuban War of Independence began in 1895, and its final three months transformed what had been a regional struggle for freedom into an international conflict, pulling the United States into the hostilities and sparking the Spanish-American War. Two weeks after the start of that war, three American ships set out to sever key undersea telegraph cables connecting the island and others in the region. In the Battle of Cienfuegos, which took place on May 11, 1898, the American ships destroyed the cable house and cut two of the three targeted lines before escaping from advancing Spanish forces.

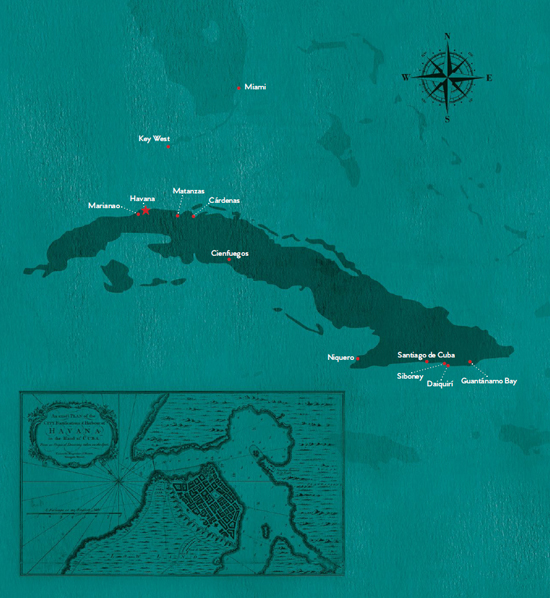

Half a century later, Cuba was chafing under the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar. A scrappy young student named Camilo Cienfuegos y Gorriarán, harried by officials for his antigovernment politics, left the country and, after a stay in New York, headed to Mexico. There he met Fidel Castro Ruz, who was plotting to overthrow Batista. In November 1956, Cienfuegos joined Castro and eighty other revolutionaries aboard the Granma, which sailed from Tuxpan, Mexico, to Playa Las Coloradas, near Niquero. Cienfuegos and only a dozen or so of the others survived Batista’s counterattack, but the invaders rallied, and Cienfuegos soon became one of the revolution’s strategic leaders, rising to the rank of comandante. Batista fled Cuba on January 1, 1959, yielding power to Castro’s forces. But Cienfuegos’s prominence didn’t last. In October of that year, his plane disappeared over the ocean, never to be found.

Cuba today represents a distillation of its incredible history. It’s a mixing pot, influenced for both good and bad by the cycle of occupation and the struggle for independence. Today the waters of Cienfuegos Bay lap at the city’s shores. Groves of mangoes line its outskirts. Horse-drawn carriages remain a respectable form of transportation. Time moves slowly, and history clings to the spectacular architecture. Each afternoon, the park at the tip of the city, called La Punta, fills with families and friends. People cool themselves in the waters off the rocky coastline or sit leisurely around a bottle of Havana Club.

Rum, to the people of Cuba, is the spirit of fire. When we opened Cienfuegos in 2006, we wanted to capture some of that mysterious Cuban essence in a bright, cheerful, welcoming refuge from the harsh frenzy of New York City. On the corner of 6th Street and Avenue A in the East Village, tucked away on the second floor, you’ll find Cienfuegos, the bar inspired by the spirit of Cuba. In this intimate space of faded pinks, greens, and yellows, the plaster cracks as if in some old house in Cuba. Each night, we light one hundred candles, one hundred fires, to embrace the past and present of rum culture and the community it inspires. Cienfuegos stands as an altar to the spirit of fire and our homage to Cuba. It has brought three of our greatest passions together here for you: hospitality, writing, and of course drinking. Our cocktails have a strong foundation in the classics, which we update into our modern interpretations. You will find both in the pages of this book.

We can’t gather around a bottle of Havana Club yet, but we can capture that sense of community by gathering around the punch bowl, which predates the modern cocktail and represents centuries of history mixed together, transforming over time as palates and environments changed. After all, gathering around the punch bowl is a tradition as old as rum itself, and it played a part in another, earlier revolution in the Americas. Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts houses the punch bowl that Paul Revere made to honor the Glorious 92, Massachusetts legislators who refused to obey the British Crown. Punch also made and unmade legendary pirates, including Bartholomew Roberts, the most successful raider of the golden age of piracy.

Unlike in America, Cuban cocktail culture never dissolved into a dark age of convenience aimed at easier, faster, sweeter intoxication. Prohibition, that thirteen-year failed experiment, inversely fortified cocktail culture in Cuba, creating its own golden age. Even today, Cuban cocktail menus prominently feature classics that barely see the light of day on menus stateside. Bartenders there have been organized as a group since 1924. At Café Madrigal, the bartender showed us his copy of the cocktail manual, which features 1,100 recipes, each footnoted with the history of the drink.

Trader Vic, a leading founder of the tiki style of cocktails, found that same respect when he visited the island in the 1930s. The skill and grace of the bartenders amazed him, and their knowledge inspired him (and, later, us). Bartenders accommodated customers’ palates without sacrificing the integrity of the drinks—exactly what we try to do in New York City, gently guiding unwary customers away from Tequila Sunrises or Long Island Iced Teas while still giving them something they will enjoy.

For decades, Cuban bartenders have practiced their craft within the confines of the broader political and economic circumstances. In this regard, America’s renewed relationship with Cuba offers much promise, and it’s exciting to think what mixologists there will be able to create without such limitations. We can’t wait to see what the future brings.

TIMELINE

Christopher Columbus claims Cuba for Spain. 1492

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, Cuba’s first governor, founds Havana. 1514

Facundo Bacardí y Massó founds his eponymous distillery in Santiago de Cuba. 1862

Cuba’s Ten Years’ War with Spain for independence ends unsuccessfully. 1878

The three-year Cuban War of Independence begins. 1895

The USS Maine explodes in Havana Harbor, triggering the Spanish-American War. After Spain loses, it cedes control of Cuba to the United States. 1898

Cuba becomes an independent republic, but America pressures the country to adopt the Platt Amendment, which allows the United States to intervene in Cuban affairs. 1902

America reoccupies Cuba. 1906

Cuba regains its independence. 1909

Fulgencio Batista leads the Sergeants’ Revolt, a military coup that ousts the president. 1933

America forgoes its legal right to interfere in Cuban affairs. 1934

The USSR opens its embassy in Havana. 1943

Fidel Castro and his army of guerrilla fighters, including his brother, Raúl, and Ernesto “Che” Guevara, oust Batista. 1959

Castro nationalizes all American businesses in Cuba without compensation. 1960

America breaks diplomatic ties with Cuba and sponsors the Bay of Pigs invasion, which fails. Cuba becomes a Communist nation. 1961

The Soviet Union moves nuclear weapons to Cuba, triggering the Cuban missile crisis, which ends when America withdraws nuclear missiles from Turkey. 1962

A boat carrying Cuban refugees capsizes in the Straits of Florida. Five-year-old Elián González survives and is rescued, triggering a legal battle between his father, who calls for his son’s return to Cuba, and his late mother’s relatives in Florida, who petition the American government to grant the boy asylum. 1999

Federal officials seize González and reunite him with his father in Cuba. 2000

Prisoners seized during the war in Afghanistan and suspected of being al-Qaeda affiliates are taken to the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay for interrogation. 2002

Castro announces his retirement. Days later, his brother, Raúl, becomes president. 2008

President Barack Obama and President Raúl Castro announce plans to restore diplomatic relations between the two countries. 2014

America eases trade and travel restrictions on Cuba, and each reopens its embassy in the other’s capital.

IT’S A MAD DASH ACROSS MIAMI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT to Terminal F, where most charter flights leave for Havana. But we aren’t going to Havana. We’re going to Cienfuegos. Our stated destination wins a series of confused looks from airport employees, which makes sense once we arrive: Just one flight per day lands on the one runway of Jaime González Airport. Head due south from Miami, and you’re there. The plane is full of elderly American tourists on state-approved tours, Cubans going home, and us. Customs officials snap our photos, stamp our passports, and there we are.

We come through customs last, emerging from the airport into the bright Cuban sun. The car rental office lies behind a mango tree. The heavy, ripe fruits fall as we wait our turn on plush leather sofas. We get the keys to a brand-new Kia, not a ’57 Chevy as we had hoped.

Cienfuegos is la perla de sud, the pearl of the South, a sleepy resort town of 150,000 people, famous for singer, musician, and bandleader Beny Moré . . . and not a lot else. The main square, Parque José Martí, has its own triumphal arch (page 142), smaller than the one in Place Charles de Gaulle in Paris and the one in Washington Square Park in Manhattan. We amble down the main thoroughfare, weaving through people lined up at an ice cream shop. We have lunch at a paladar, the Spanish word for “palate,” but in Cuba it refers to a family-owned and family-operated restaurant. The owner of the Los Lobos paladar has a strong affinity for rock music. A framed Ozzy Osbourne watches as we drink a couple of Cristal beers. The chef peers out to see if we’re enjoying our chicken cordon bleu, a house specialty. On the roof of the Palacio de Valle, we find the first signs of Cuban cocktail culture—aside from our hotel’s sad rum and coke, no limes available. The Palacio’s rooftop bar features a full cocktail menu and two neatly dressed bartenders. We slowly sip a Ron Collins and Havana Special in the glorious afternoon sun.

Not far off, we spy the tip of La Punta, the dagger of land that juts into Cienfuegos Bay. Everyone seems to be heading there, so we follow. At the tip lies a park with a bar, and the cantinero (bartender) claims to make the best mojito. We take him up on his offer, and it’s damn good. But fresh limes, we discover, are either hard to find or maybe not highly valued. It feels like half the city is here in the park, though, swimming and running around. A group of teenagers huddles around a bottle of Havana Club with plastic cups. There’s a fish roast later that night if we’re interested.

Heading back through the city, we come upon a small basement bar. The cantinero, Manny, wears a giant gold chain with a dollar sign pendant. We still haven’t had a daiquirí, so we make amends. Manny announces that he’s going to make it special for us and produces a fantastic Chivas daiquirí. Havana Club—the Cuban rum so special that American bartenders try to smuggle it out when they leave the country—is the norm for Manny. Chivas, the blended Scotch that our parents served when they had company, is more special here. But Manny’s daiquirí is delicious. He proudly shows us the wine cellar and is shocked to learn that two of us are cantineras—female bartenders. Nevertheless, he likes the look of our daiquirí when we show him a picture.

All roads lead to Havana. That’s what you have to remember when lost and driving though an area with more horse carts than cars. Before this trip, we didn’t know that horses could give dirty looks—until we accidentally blocked one with our Kia. All roads may lead to Havana, but before you arrive the Policía will pull you over. Maybe the horse told the officers to watch out for us. They pull us over and check the rental agreement, our driver’s licenses, and the trunk of the car. They seem mildly amused either by our plan to drive to Havana or by the panic in our eyes when it looks like this road might lead to a Cienfuegos jail cell. They tell us that we are “very pretty girls” and to “be careful.”

The wide-open road to Havana is in better shape than most in Brooklyn, and, better yet, no horses. Fields of sugarcane line the highway. The cows look painfully skinny. A couple of guys flirt with us from their car. A few hours later, Havana appears in the distance.

But some of the most confusing road signs we’ve ever had to decipher thwart our arrival. Once again, we’re lost. Even on the outskirts, Havana doesn’t have the same resort-town sleepiness of Cienfuegos. It feels like we’re in the Bronx trying to find our way to Times Square. We’re in the right city but a world away. It turns out that we’re in Guanabacoa, in the eastern part of the capital, an area famous for the Afro-Cuban religion Santería. A few lefts and a few rights, and signs for Habana Vieja, the old part of town, come into view. To make sure we’re reading the signs right, we circle the roundabout one more time. That’s the joy of a roundabout: You don’t have to make a decision until you’re ready.

As we get closer, the streets narrow, and we enter an old, worn postcard. The gorgeous buildings are falling apart. Colorful walls crumble, exposing dark substructures. Laundry hangs from windows. The dome of the National Capitol Building—El Capitolio, which housed the Cuban Congress and now contains the Cuban Academy of Sciences—rises above us. We pull over to orient ourselves on the map. The driver of a bike taxi pulls up alongside, says “No Mafia,” and asks if we need help. He circles around the car and shows us where we are. Up two blocks, make a right, take it to the end, and that’s the Malecón, the broad roadway, esplanade, and seawall that stretches from Havana Harbor to the Vedado district, where we’re staying. It’s our final road to Havana.

Since the recent economic reforms, a plethora of paladars have transformed some city streets into restaurant rows. People holding menus throw themselves at you. The air smells of gasoline. Heavy black smoke pours from the ’57 Chevys and the Soviet-era Ladas.

During dinner at Café Laurent, we sip Havana Club Ritual and Ron Santiago 11 Year. The daiquirí here is pretty, but it’s still missing the lime juice. The real cocktails come at Café Madrigal.

Owned and operated by film director Rafael Rosales, Café Madrigal is the first outpost of real Cuban cocktails that we find. Fresh lemon juice mixes with honey for a delicious Canchanchara. (See our version, the Honeysuckle, on page 132.) The bartender, Ricardo, shows us his bar book, Cocteles Cubanos, which explains the history of the Canchanchara. Then he gives us his recipe for the Mai Tai. A political science professor from St. Louis, who now lives in Cuba, plays the mandolin alongside the college-age guitar player at the microphone. We end the night with a round of tequila shots, just like at home.

Havana is city of historic bars. As often happens, historic bars die in time, stunted by the moment that made them matter in the first place. El Floridita seethes with tourists who snap pictures next to the Hemingway statue. Papa Doble is good, but nothing about the space makes you want to sit awhile. Sloppy Joe’s looks like any other American bar. The vibrant center of living history is Bodeguita del Medio. Signatures of prior customers cover every inch of the place. Bartender Arturo is as old-school as they come, as quick with a light for a cigar as he is with a drink. The mojitos are good, too. We sign our names on barstools, listen to the band, and drink our mojitos.

At that moment, Havana feels perfect.