With Frick departing for Egypt, Peck immediately began completing his team of players. The Navy was now fully integrated into the squadron with Morgenfeld and Heatley forming much more than just “token squids” in the initial cadre of 4477th TEF MiG drivers. In January 1979, Morgenfeld and his wife finally packed up and moved from Point Mugu to Nellis: “It was all being made to look like I was there as part of a normal exchange tour,” he explained.

The Department of the Navy was paying 30 percent of the program’s costs, and its pilots would be responsible for the hands-on training with the Navy and Marine units that would eventually come to Tonopah to be exposed to the MiGs. Regarding the selection of the Navy pilots Oberle recalled: “The Navy would select the guys they wanted and send them to us, but we had a veto if we felt that they weren’t the right person. Adm Gilchrist was the guy over at Miramar, head of the Navy input. He was very supportive of our operations over there. If we made one phone call back over there and said, ‘Send somebody else,’ they’d do it immediately.”

It was a Navy pilot who is credited with naming the 4477th TEF. “Heatley came up with the Red Eagles,” Peck told me. “He stuck to it like a frog on a June bug; he just wouldn’t let it go. I said to him, ‘Heater, that is just too provocative. We can’t go putting on a Red Eagles patch – that’s the Russian fighter Weapons School or some damn thing!’” But Peck considered the name over the next few weeks, eventually deciding, “What the Hell? Let’s use it.” And so the name became official. By then Smith was gearing up to lead the Air Force Thunderbirds demonstration team, so his replacement at Langley, Joseph “CT” Wang, pushed its approval through the official channels at TAC.

While Peck and his team entered the final stages of preparation at Tonopah, the maintainers handpicked to work the MiGs remained at Groom Lake to continue preparing the assets for their move to the TTR. The maintainers made only limited changes to the MiGs to make them ready for flight. One such change was the installation of a tunable UHF radio, and another was a conventional pitot-static system for measuring airspeed and altitude, thus overcoming the pilots’ unfamiliarity with the “kilometer per fortnight” scale, according to Peck. This translated into a new airspeed indicator (ASI) and a new altimeter. The G-suit valve, which supplies compressed air to inflate the pilot’s G-suit and help prevent loss of consciousness during heavy maneuvering, was fitted with a converter to allow the Americans’ G-suits to plug in; but other than that the MiGs’ systems were left untouched.

March 1979 saw the Red Eagles’ pilot roster grow. Capt David “Marshall” McCloud, an experienced F-4 pilot who, like Henderson, had previously flown the F-106 with ADC, was hired by Peck from the Aggressors. He’d been an F-5E instructor pilot, flight commander, chief of academics, and detachment commander for the 64th FWS and 65th FWS since October 1976. McCloud became “Bandit 10.” He was followed in May 1979 by Karl “Harpo” Whittenberg, “Bandit 11.”

But all was not well with Morgenfeld. “I never found out why, but it became apparent that I had been passed up for command of a Navy fighter squadron once my tour of the 4477th TEF was over. I couldn’t understand why – I had a reasonable reputation in the F-8, had my Masters degree, and had graduated number one in my test pilot class, and I was now flying MiGs – so I had done everything right. So, I elected to leave the Navy.” Morgenfeld was the third 4477th TEF pilot to leave the unit before the program could bed down at Tonopah. Although administratively speaking he would remain a member of the unit until November, he had already started looking to his career outside the Navy and was lining up a job as a test pilot with the Lockheed “Skunk Works,” the aerospace giant’s black arm.

He suggested that he be replaced by Lt Hugh “Bandit” Brown, who was flying with VX-4. Morgenfeld had flown against, and with, Brown at Point Mugu, and knew the man well. “He was very good pilot with a nice mentality: he wasn’t all balls and no brains. He was a good pilot without being brash, and we just felt that we could not accept cowboys up there. We had no desire for the swashbuckler bravado thing. We also didn’t want people who had a problem living in the dark, or were unable to do anything without taking the credit. Hugh was certainly like that: a wonderfully warm man with a great sense of humor. He was a great guy to have on your team because he would always ask, ‘What do you need me to do?’”

Morgenfeld’s suggestion was endorsed and approved by the Navy. In April 1979 Brown and his wife, Linda, moved with their two young boys from Camarillo, California, to Nellis. In May 1979, he became “Bandit 12.”

The squadron continued flying its leased 404s to Tonopah and back several times a day. For transit flights to and from the site, the 404s were parked close to Nellis’ Base Operations building, and the maintainers would be flown out to Tonopah by one of the Red Eagle pilots as soon as ten or so of them were ready to depart. Throughout, the pilots maintained their fighter proficiency by flying F-5 Aggressor missions during the day, and many remained active participants in the Aggressor program itself.

Oberle characterized three distinct changes in the Red Eagles’ integration with the Aggressors: “In the beginning [January 1977 to late summer 1977], when we were getting the runway fixed and we were working on the airplanes, I spent a lot of time flying with the Aggressors; two thirds of my time with them, and a third of my time getting things up and running. Then [late summer 1977 to summer 1978], when we began to get things formalized – we had a runway and we were doing things ‘up north’ – 75 percent of my time was spent with the Red Eagles. When we finally became fully operational [1979 onwards], I spent almost 100 percent of my time with the Red Eagles.”

Flying with the Aggressors, and the insistence that the highly skilled Navy TOPGUN pilots complete the Aggressor checkout, did more that just keep the pilots current: it was the cover for their presence at Nellis. To the outside world the Red Eagles would have appeared to have been normal Aggressor pilots.

One day, Ellis walked into Peck’s office and declared: “Boss, we need a truck.” Peck responded in the affirmative: “OK, what kind of truck do you need?” Ellis’ response was priceless: “Actually, we already bought the truck, what we really need is a check.” The whole scene must have been even more peculiar because the maintainers were not expected to conform to the Air Force’s 35-10 dress regulations: to appear less conspicuous they dressed as civilians, they sported pork chop sideburns and even mustaches, and most wore jeans and tee-shirts.

When a sudden injection of cash was required, and for occasions like this, Peck would visit Mary Jane Smith at the Pentagon. She would duck behind her desk so as to be hidden when she saw him coming, and would always ask him: “Is this going to cost me tens, hundreds, tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands today!?”

The 18-wheeler Kenworth truck allowed Ellis and his maintainers to haul spares and parts for the MiGs from all over the country. Oberle noted that: “Bobby was a phenomenal scrounge rat. He could go and get anything, and it was amazing the stuff we’d see that he had brought in here. Where he’d got it from we didn’t know and didn’t ask. He was phenomenal, and he attracted other guys like him from the enlisted ranks.”

Ellis brought “junk” by the truckload, much of it salvaged from the DRMO – Defense Reutilization and Management Office – salvage yards that housed old military hardware suitable for recycling. One day the maintainers called Peck down to the Indian Village, and while hesitant to go because of the mud that permeated everything down there, he agreed. When he got there he saw three wheelless trailers arranged in a U shape, between which pierced steel planking (designed to be used for temporary runways) provided a solid floor. Overhead, a parachute canopy covered the three trailers and kept the elements at bay, and beneath that was a small assembly line. Astounded at their resourcefulness, Peck was witnessing his men assemble Jeeps from scrap metal and DRMO-salvaged chasses. The men presented him with the first vehicle, the “command vehicle,” and from then onwards he never had to walk at Tonopah.

“We quickly ran out of space,” Peck recalled. “We were short sighted in our planning, needing facilities for AGE [aircraft ground equipment] and vehicle maintenance as well as storage. We ended up begging for some inflatable hangars from Holloman. They were from the Emergency War Reserves supply, and they didn’t want to give them to us, but eventually we got them.” A few hundred yards from the Indian Village was the apron and its three newly installed hangars. “There was no dedicated hangar for the MiG-17s and the MiG-21s; the airplanes were just worked on in whichever hangars they happened to be in at the time,” Peck said.

One of the more problematic issues that Peck had to deal with at Tonopah was certification and quality control of the squadron’s POL tank, which sat on the southeastern corner of the small operating apron. Given the base’s remoteness, this had to be built from scratch from the Phase I construction funds, and it took time to check the device to ensure that the fuel distributed was not contaminate.

As he concentrated on the actual base and its infrastructure, Peck instructed Oberle to look at the “TX course” – the type conversion program – that future Red Eagle pilots would have to go through to qualify to fly the MiGs. Peck wanted future pilots to be armed with documentation, and to be put through an official TX course. “I actually harmonized the course, then formalized the checkout program to include grade books.” It was a start, but time would show that it was not enough.

On July 17, 1979, MiG operations at Tonopah began. In the days before, six MiG-21s and two MiG-17s had been flown in from Groom Lake. Peck flew the first MiG-21 sortie from Tonopah, and Oberle the first MiG-17.

Coordinating the first operational squadron exposures, Oberle remembered, was a matter of identifying units that were coming in to participate in Red Flag, or that were deployed in specifically for CONSTANT PEG. In the case of the former, a squadron would deploy to Nellis with absolutely no idea that they were going to do anything other than Red Flag. However, for the duration of the two-week exercise, two or three pilots per day would be taken off of the flying schedule and told instead to report to another building on the Nellis compound for some unspecified training. In the case of the latter, the squadron would usually send a small cadre of six aircraft and as many as eight pilots.

The Blue Air pilots, no doubt mystified, would arrive at the 4477th TEF’s plain white trailer vans located in the FWS parking lot, away from the main hub of flying operations. There they would be greeted by one or two unfamiliar pilots wearing the yellow and black checkered scarves of the Nellis elite beneath the collars of their flight suits, and on their left shoulders was a circular patch depicting a Soviet-styled red eagle with wings spreading either side of a white five-point star. In red at the bottom of the circle were the numbers and letters “4477th TEF.” At the top was written “Red Eagles.”

The Blue Air pilots would be seated in a small briefing room in the trailers, and were finally read into the CONSTANT PEG program. “They had the fear of God hammered into them.” Peck said. “We left them in no doubt that any divulgence of the program’s secrets would be dealt with in the most severe of ways.” The Red Eagle pilots would brief them, usually in small groups of two or four, about what they were going to see the next day, how the sorties were going to be sequenced, and what would be demonstrated airborne.

The next morning the Red Eagles pilots left Nellis early, arriving at TTR in the Cessna or borrowed Aggressor T-38. As the first two Blue Air pilots briefed the sortie at Nellis and stepped to their jets for take-off, the two Bandit pilots would be getting ready to man the MiGs. Approaching the airfield at a prearranged time, and broadcasting their position on the Red Eagle’s radio frequency, the Blue Air pilots would announce their imminent arrival. Oberle explained: “We’d be in the cockpit, and as soon as we heard them check in, we’d crank and taxi out to the end of the runway. When they got overhead we’d takeoff and they would join up with us to get their first look at an airborne asset.”

A record of each pilot to undergo exposure to the MiGs was filed at Tonopah, allowing it to determine who had received what training, and against which aircraft, for future reference. This was critical because not only was it desired that the Red Eagles expose as many frontline fighter pilots as possible, but also because each pilot could participate in three different types of exposure with each MiG type during the course of his career.

The three-stage exposure program applied now differed in its overall aggression and tone to that which had been flown prior to the arrival of the MiGs at Tonopah. Whereas the exposures prior to September 1979 had essentially gone straight for the kill with the dogfighting on the first sortie and 2 v 2 or even 4 v 2 on the third sortie, the new regime took a more gradual approach. Stage one, the first exposure, incorporated a performance profile (PP), followed by a brief stint of basic fighter maneuvers at the end if fuel allowed. The PP constituted the new, more gentle introduction to the MiGs and would often start with an interception using the visiting pilot’s radar, followed by a visual join up. “You’d be there in this little biddy MiG-17, with your head sticking out above the canopy rail, and the guy’s eyes would just about pop out of his head as he joined up with you in formation,” Peck chuckled.

The PP had actually been devised in late 1967 by Maj Duke Johnston, the chief of air-to-air at the F-4 FWS at the time, and the man who had been selected by TAC to be the project pilot for operational exploitation of HAVE DOUGHNUT. Johnston had devised the profile around key criteria that would demonstrate how one aircraft performed compared to another, and it was a scripted precursor to engaging the DOUGHNUT MiG in unscripted dogfights. It had since been adopted by test pilot schools and follow-on foreign military exploitation (FME) programs alike.

The PP started with the Red Eagle instructing his adversary to take up various formations, according to the pre-briefed flow, so that he could show the MiG’s strengths and weaknesses in direct comparison to the visitor’s mount. “I’d tell him to look at me from various angles, and then I’d tell him that we were going to have a race,” Peck remembered. In order to demonstrate the relative differences in acceleration, both aircraft would go to afterburner and accelerate to 500 knots. Then the PP would become more involved. Against an F-4 pilot, for example: “We would have him fly formation with us and then tell him we were about to do our best sustained turn. His job was to follow us. Well, he couldn’t, because the turn circle in the F-4 would just puke through. The lesson there for the F-4 guy is that if he wants to fight a MiG-17, he can’t turn with him. If the MiG-17 turns, then he has to go up to become like a stitch in a sewing machine, riding his turn circle every time the MiG starts to turn. Maneuvering into the vertical to stay within the same plane (arc) as the MiG’s turn was the only way to do it.”

There were of course rules, but these were standard Air Force training rules, according to Oberle: “We had a 5,000ft floor AGL [above ground level], a 1,000ft bubble around each airplane that you weren’t to penetrate, and the idea was not to get into a slow-speed rat race but to try to learn to maintain your energy and fly the strength of your airplane against the weakness of the MiGs.” Teaching pilots who’d never flown against the MiG-17 was an exciting experience for Peck, and it wouldn’t take long for the Phantom driver to truly recognize that the excess thrust he had in comparison to the tiny MiG could be used to counter the Fresco’s exceptional turn capability.

Sortie number two saw a continuation of BFM. The Red Eagle pilot would invite the visitor to “take up a perch,” which is to position themselves a set distance (usually 6,000ft) away so that they could do some basic BFM. As the opposition pilot’s proficiency increased, the MiG would be flown in a correspondingly tighter turn to challenge them and get them used to it. That would be followed by a defensive perch, said Peck: “He would go out in front and we would show him how difficult it was to see a MiG at your six while pulling 5G.” For Peck this lesson was one of the most valuable: “We were using to looking at the gigantic planforms with smoking engines, and suddenly we’re teaching these guys to look for canopy glints and things like that. If a MiG is converting to your 6 o’clock, a canopy glint may be all that you see because he’s pointing at you the whole time and his visual cross section is tiny.”

By the time the visiting pilot was receiving his third exposure, he would be told to execute “butterfly” set-ups – where the two fighters would line up side-by-side and then turn into each other and pass canopy to canopy; they then fought to see who could gain the tactical advantage. After this, more tactical radar intercepts would be flown, provided there was enough gas remaining. The intercepts allowed the pilots to see the ranges that the Soviet jets would appear on radar, and to see what the electronic indications that the MiGs’ own range-only gun radar would look like and sound like on a radar warning receiver.

For the Red Eagle pilot, a typical day would produce two MiG sorties, following which he flew back down to Nellis to individually debrief the men he had flown against. As more pilots qualified to fly the MiGs, a rota system was developed to allow a pilot to spend one day at Nellis debriefing the visiting pilots he had flown against the day before, then briefing the pilots he was to fly against the next day. That night, or early the next morning, he would fly up to Tonopah and spend the whole day there. The next day the process would repeat.

Although two types of MiG and three sorties per MiG resulted in the maximum number of sorties per Blue Air pilot being limited to just six, few actually experienced that many. For a pilot attending Red Flag, he would be fortunate to fly three sorties against the MiGs on the day he had been taken off the normal flying schedule. The next day he was back onto the Red Flag schedule and two other pilots from his squadron would be whisked away for the day. There were exceptions to that rule, and some squadrons visiting Red Flag would use their two-seat trainers to make sure that as many pilots as possible got exposed to the program before their visit to Nellis was over.

In reality, it took two or three days to get a single pilot through the entire exposure program, and weather aborts and maintenance aborts by either party would mean that that sortie was lost forever – it was not rescheduled, it was tough luck.

A number of factors influenced the small number of sorties available. The first was that the fuel fraction of the MiGs – the amount of time they could remain airborne – was exceptionally short and this limited the amount of “playtime” that each MiG would have; and the second was that with the almost certain shock of Buck Fever that the visiting pilots would experience on first sighting the MiGs, the first exposure would be spent helping them to pull their jaws from the depths of the cockpit floors. In this sense, CONSTANT PEG would work along similar lines to Red Flag, allowing the pilots, astonished by what they were seeing, the luxury of becoming accustomed to the MiGs before they finally realized that there was nothing magical about them – they were simply other jets.

Because neither the Fishbed C/E nor Fresco had any air intercept radar, Peck hired his own GCI controllers. Jim “Bluto” Keys and Bud “Chops” Horan were brought in to work the radars at Nellis. Their job was to be the MiGs’ eyes until they came within visual range of their quarry. With no table of allowance assigned to the flight, Peck wasn’t exactly sure what level of manpower he was allowed to accrue, so administratively he was in a state of limbo. More pressing was that despite the experience of the Red Hats and HAVE IDEA with the Tumansky R-11F-300 engine of the MiG-21F-13 Fishbed C/E and the VK-1F of the MiG-17 Fresco C/D, no one really knew how long they were going to last. In the end, Peck said, “We just ran them until they didn’t work any more.”

Meanwhile, former Apollo astronaut and the creator of the Red Hats, three-star general Tom Stafford, turned up at Tonopah, ostensibly for a tour of the facilities and a look-see at the security arrangements. In actual fact, Stafford was there to do a site survey for the F-117 program. Stafford was now the DCS of Research and Development at the Pentagon, and was Bond’s boss.

What he found at Tonopah impressed him. But there was an aspect of the Red Eagle’s facility at Tonopah that would need to be looked at: as a money saving measure, they had not concreted the entire apron: “and that caused us a lot of grief, because the jet fuel mixing with the asphalt just turned it into a load of goo. That was one thing which I wish I had done differently,” Peck admitted. Regardless, it was something that could be remedied with ease when the F-117 money arrived. Thus, the wheels had been set in motion for a second phase of construction that would start readying the airfield for the eventual arrival of the F-117.

On August 23, 1979, “Bandit 12,” Hugh Brown, was fighting a Navy F-5 Adversary in his MiG-17F when he pulled back on the stick and the Fresco entered a spin. Accounts of what followed differ from one person to the next, but it is agreed that he had recovered only partially from the spin when, as the ground rushed up towards him at an alarming rate, he entered a new spin. This second spin was unrecoverable.

Brown made no attempt to bail out from his MiG, and the aircraft impacted the ground and disintegrated into a deep hole. He could have attempted ejection, but Morgenfeld believes that, like so many did, he would have felt “a tremendous sense of responsibility for flying what were vital national assets. He was going to do his very best to bring it back, and I think that he just stayed at it too long and worked too hard to do that.” Because of the MiG-17’s severely limited fuel fraction, most of the exposures that it participated in took place over, or very near to, the Tonopah airfield. Thus, when the crash occurred, Brown had been right over the airfield boundary. Help was on hand quickly, but there was nothing that could be done. The impact had been at high vertical speed, and Brown had died instantly.

It was a tragic and shocking loss, all the more so because he was a family man who left behind a wife, Linda, and their two sons, Brady, three years old, and Brian, 11 months old. Linda told me: “Hugh was so proud when Brady was born that he had a special squadron name tag made for the occasion. [It] read, ‘I am a Daddy.’ He had a great smile and was very intelligent; his love of life and music was intoxicating, and he could dance like James Brown!” Brown had come from a family with a history in the US Navy, she said. “He was born May 21, 1948, in Roanoke, Virginia, and was the eldest of three siblings. His dad, Melvin Crocket Brown, was a chief in the Navy who had retired after 30 years of service. Hugh’s given name at birth was Melvin Hugh Brown, after his father. He never liked Melvin, so he signed everything ‘M. Hugh Brown.’ Being a Navy brat gave Hugh the insight into the Navy life and reinforced his patriotism, and by high school he already knew that he wanted to fly Navy jets.”

Following graduation from the Naval Academy in June 1970 and until a slot opened up for him to begin pilot training, Brown was sent on a brief exchange to the Air Force’s Eglin AFB, Florida. It was here that he’d met his soon-to-be-wife:

We met in June 1970. Folks kept saying, “Have I got a guy for you!”, and, “Have I got a girl for you!” We saw each other across the room and he smiled at me. I was 18 and he was 21, and he stood out from the Air Force officers as his uniform was khaki.

Hugh was also a tall, handsome guy with curly brown hair and brown eyes that smiled at you. In August 1970, he asked me out for my 19th birthday; we had dinner at the Officer’s Beach Club at a table next to the Thunderbirds. We dated for two years as he worked his way through flight training in Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, and got his Masters in Aeronautical Engineering at the University of North West Florida. We were engaged April 1972, and in July that year he earned his wings of gold. In September we were married, and then we drove across country to San Diego, California, for our first duty station at Miramar NAS [Naval Air Station].

Brown’s first assignment was to the Pacific Fleet Adversary Squadron, VF-126, which had been flying A-4 Skyhawks as “Bandits” for the Navy’s West Coast fighter squadrons since April 1967. He amassed 1,000 hours in the squadron’s TA-4J Skyhawks before being assigned to an operational tour on the F-4N Phantom with VF-21. Next he joined VF-121, the Pacific Coast Replacement Air Group, as an instructor pilot. In 1976, Brown spent six months onboard the USS Ranger, and then went to TOPGUN. And that’s probably when this “loving and sentimental husband, good cook, and an awesome dad” of a fighter pilot was exposed for the first time to the MiGs of HAVE IDEA. Following his successful completion of TOPGUN he was assigned to VX-4.

For Linda, August 23, 1979, started like any other Thursday. But it would end very differently:

Our alarm clock rang. Our baby boy cried for his bottle. And the sun rose over the horizon. After breakfast, I kissed Hugh goodbye and off he went to work. I was home preparing dinner when the doorbell rang at approximately 1730. Gail Peck, his wife, Peggy, and the chaplain were standing there. At first, I kiddingly told them they were just in time for dinner. Then, I realized that something terrible had happened. The chaplain and Gail walked me to the sofa in the living room as Peggy went into the family room with the boys. Gail spoke softly and said: “We’ve lost Hugh.” Those words will never be erased from my mind. The tears came uncontrollably, realizing that life as we knew it would never be the same.

Brown’s death that day changed many people’s lives forever. For Linda the impact was brutal and unrelentingly hollow: “They said Hugh was flying a test in an F-5 and it was very confidential, so I had very little detail.” The Air Force told Linda Brown nothing more, but local papers quoted an Air Force press release that was surprisingly candid: it talked about “a specially modified test aircraft,” code for a MiG, and was specific enough about the location (“90 miles northwest of Las Vegas”) that even a casual observer would notice that Tonopah’s airfield was very close by. But Linda had no reason to be overly suspicious, and believed that her husband was simply a Navy pilot on exchange with the Air Force’s Aggressors – a cover story reinforced by the fact that he never wore a Red Eagles patch, instead opting for the Aggressor patch.

For the maintainers out at Tonopah, the grim job of recovery that Thursday afternoon would be imprinted on their minds for the rest of their days. The small unit had no dedicated accident investigation resources, and the program was so secret that it was simply impossible to convene a full-scale, trained, mishap board without jeopardizing the whole effort. Instead, the maintainers and pilots found themselves tasked with the grisly and grim responsibility for photographing the scene of the crash, recovering Brown’s remains, and burying what remained of the MiG to keep it from prying eyes. The MiG had made a hole in the desert floor, and the men took it in turns to dig out the remains. They could each manage only about ten minutes at a time, according to Oberle, who was one of the recovery team. They were doing a job for which they had not been trained, and one which Air Force maintainers in no other unit would have been asked to do. “It was one of the most difficult things I have done,” said Oberle.

As Linda sat in shock, Peck called her parents in Florida. They came to Las Vegas the following day. That evening, Peggy Peck stayed the night and offered sedatives to help Linda sleep. For others, Brown’s death invoked a sense of guilt. Morgenfeld was on vacation in New York with his wife, Norma, when he got a call that afternoon from Heatley. “He told me that Hugh had gone down and that he hadn’t got out. Even though he couldn’t say anything more over the unsecure line, he didn’t need to say anything else. I was stunned, and I went out and sat down on the front porch by myself trying to get my thoughts together. I felt a sense of responsibility because I had picked him to go out there. Chuck was pretty broken up, bless his heart. He had been one of the first to arrive at the scene.”

Linda recalled: “Hugh always spoke highly of the team he worked with, especially the non-commissioned officers. I had never met the men that Hugh spoke of until his death, when they all attended a memorial service to show their support. It was very touching.” Linda acted decisively and as best as she knew how:

I sold the house and left Las Vegas, never looking back. I took Brady and Brian to my parents’ home in Destin, Florida. There I was able to grieve and take care of matters. That time was very difficult for us all. My parents had always been there for me and they loved Hugh as their son. I was home for six weeks when I decided to return to San Diego where we had started our life. It was a good decision. I joined a support group for Navy widows, which was invaluable, and I returned to work part-time at the school at which I was employed before Hugh and I had had our children.

As Brady and Brian grew up, I told them about their dad being a brave fighter pilot and how he was the best of the best and he was on a secret mission when he was killed and I did not know any more information. I always told them that I was hopeful that we would someday know.15

Henderson was the ops officer, and a lieutenant colonel, at the 64th FWS squadron at Nellis when he received a call late one evening. “It was from my wing commander, one-star general Tom Swalm, and he told me that I was to go and meet with two-star general Robert Kelley, the Tactical Fighter Weapons Center commander, the next morning. He said a couple of things, but one of them was that I could not talk to anybody. I knew at that moment that it was probably going to be Gail getting fired, and that I was probably going to get the squadron.”

It was while working Cope Thunder at Clark AB in the Philippines in 1977 that Henderson first heard that a squadron of MiGs would be forming. “I wanted to be a part of that outfit: the MiG was the ultimate Aggressor and it couldn’t get any more accurate than that. But when I called Glenn Frick at Nellis to throw my hat into the ring, they had already chosen their people. One of the guys I roomed with, Gerry Huff, had already gone back [to Nellis] to be a part of the group.”

Some squadron commanders in the late 1970s survived losing a jet without being fired, but Peck would not. Kelley, who was administratively directly responsible for the 4477th TEF, took less than two weeks to fire him. Kelley was “a tough-as-nails kind of commander,” Henderson said, “and he was very uncomfortable with Gail and all that he was doing outside of the Nellis community – it was so different from a normal fighter squadron. Gail had no choice but to deal directly with the Air Staff, the logistics people, and other organizations.” Kelley probably based his decision not only on the fact that a jet had been lost and Brown killed, but also on the revelation that Brown had previously spun the Fresco in similar circumstances, but had allegedly failed to inform Peck.

When Henderson met the TFWC commander the next day, his fears were immediately confirmed. “He told me again: ‘Don’t tell anybody. We’re going to meet with Gen Creech and get him to approve you as commander.’ So, I go to the airport the next day and I see Jose Oberle, and he’s on the same flight. When he sees me he knows what’s going on – he’s devastated because he knows that Gail’s going to be fired.” Kelley, Henderson, and Oberle boarded the same flight and headed to Langley AFB.

Oberle was to brief Creech on the mishap as a subject matter expert on the MiG-17 – he was required to explain to the general how the MiG would stall violently even when flying fast. Oberle’s presence was required despite the fact that an accident investigation had been hastily convened and executed. There were photographs of the site that had been taken by the maintainers, but the investigation was close hold and its scope and purpose were limited by the usual standards. Better to have Oberle personally brief the general based on what he had managed to find out about the mishap. Once that briefing was over, Kelley wanted to introduce Henderson to the TAC commander for his blessing as the new Red Eagles commander. Hendersen reflected: “It was a tragedy for Gail, and a situation where we were very good friends before that, and now we are again, but at the time it was incredibly difficult for him to adjust to that slam. He’d been so involved, and they were barely started, barely off the ground and he just gets pulled right out of there.”

It was a bitter sweet moment for Henderson, and one made all the more ironic because, he confessed: “The week before, Gail was in my office and somehow the subject came up about what I wanted to do next. I told him, ‘I want your job!’ Oh, it was very untimely! I thought that I might succeed him a year or two later, but I had no inkling.”

On the flight to Langley, Oberle and Henderson sat separately from Gen Kelley. Oberle briefed Henderson extensively on how the outfit had been formed and what the outfit had just been through, including the horrific trauma of recovering the remains of a close friend and squadron member at the crash site very close to the airfield. “Jose gave me a complete thumbnail of what had been going on because I didn’t know a lot of these things. They were going through a lot of traumas; there are problems when you’re that secretive,” Henderson explained.

It was only after arriving at the officers’ quarters at Langley and Gen Kelley had departed for his own room that Oberle was permitted to pick the phone up and call his boss. That Peck learned of his dismissal not from his immediate superior, Kelley, but from a subordinate was a final insult. It was, according to Henderson, “a very brutal and cruel way to do things.”

“Risk assessment wasn’t a common thought at that time,” Peck told me, “and by the time we were flying the MiGs we had complete confidence in them.” And there was every reason to do so. HAVE IDEA had not resulted in a single write-off or fatal mishap, and the FTD’s exploitations before that had been noteworthy for their excellent safety record in this regard.

“It was a pretty hard pill to swallow,” Peck admitted. “You go from being the superstar and the darling of the world to being an outcast. From that moment on, the iron doors of CONSTANT PEG shut on me. I was told nothing more about the program. I was completely shut out.” Peck was dying by the sword, just as he had lived by it – the security arrangements that Muller had designed, and Peck had approved, were now being applied to the former commander.

Henderson took charge of the 4477th TEF on September 6, 1979. He became “Bandit 13” that month. “There was no magic solution when I came into the squadron. Jose had said to me: ‘The first person you have to sit down with is Bobby [Ellis]. You have to get him on your side.’ So, that’s what I did.”

When Henderson took over the flight, it consisted of only 30 people. “I walked into the squadron and I called a meeting of everyone. I explained how the events of the past 48 hours had unfolded and what guidance I had received from Gen Creech and Gen Kelley. I then asked for a private meeting with Bobby Ellis where I requested that he work with me to get past the turbulence of a sudden change of command.”

Ellis was businesslike, but flustered by the proceedings of recent days. “He probably viewed that squadron as being his own. He was wary of me and appeared to be suspicious of what impact I might have upon ‘his world.’ He wanted to let me know that he was in charge, not me. We ended the meeting with him sort of loaning me the squadron to do what I needed to do with it. Over the next nine months he delivered on that promise and we developed a harmonious working relationship and the job got done.”

The presence of a number of characters in the Red Eagles helped break the inevitable tension that followed Peck’s sudden departure. When Henderson first arrived at Tonopah to take over the squadron, he was taking in the scenery at the remote airfield – “very austere, high desert, 5,500ft above sea level” – when an incongruous vision presented itself:

It was one of our vehicle maintenance guys. His name was Billy Lightfoot. He’s got this Fu Manchu beard and, and he drives up in his “vehicle.” I use that term very loosely: it is a chassis with a seat and a steering column and an engine, and that’s what he comes driving up in. He made it out of parts that he got God knows from where. More than once I was left with trying to explain to my DO or the TFWC commander why I needed a vehicle that had only an engine, a chassis, a steering wheel and a seat … and who was that tiny man driving the vehicle who looked like Yosemite Sam, full beard, unkempt hair and all.

When the squadron was activated at Tonopah in 1979, it was envisioned that the maintenance men would live in the town of Tonopah and the pilots would fly to and from each day in the Cessna 404. Part of the cover story was that the maintenance men were civilian contractors and not active duty personnel. They were told to wear civilian clothes, let their hair grow out, and everyone went by first names or call signs. It did not take long for them to acquire the “civilian look.” Some simply let their hair grow to where it touched their ears, some grew handlebar moustaches – Bobby Ellis always had a buzz cut. The senior officers in my chain of command were less than thrilled with the “look” but went along reluctantly.

The maintainers came from an enormous pool of candidates:

The pool was probably five to ten times larger than the pilot pool. Many of the crew chiefs and various specialists were drawn from the test community, with strong ties to Edwards AFB. Edwards was a filter similar to the FWS filter for the pilots at Nellis, in that there was a vetting that occurred before they ever got assigned to Edwards. The maintenance personnel there were always tasked to work on a variety of systems, including some foreign systems, and had to be creative and flexible. The small Edwards community was easy to track and reputations were well known, both good and bad.

When it came to hiring from outside of the test community, it meant searching a database and choosing potential candidates. All enlisted personnel worldwide were in a microfiche database, which was updated several times a year. Bobby Ellis would search the database, identify potential candidates, check up on the unknown candidates by calling a trusted agent who knew the candidate or worked with the candidate. Then, if the candidate looked promising, Bobby would fly to his base and interview him. If it were a fit, he would start the reassignment process. The military personnel center would put a special code on each of the 4477th enlisted man’s records. This prevented reassignment sooner than six years, with additional years to be negotiated down the road. This was, most commanders believed, essential if the maintainers were ever going to become truly skilled at maintaining the enigmatic MiGs.

Henderson was now responsible for the continued development of TTR and he was soon attending meetings with contractors accordingly:

Because the initial budget was so small it was envisioned that it would be a bare base operation with a radio-equipped Jeep for air traffic control, a single runway with no parallel taxiway, and three very small hangars. We envisioned an operation more like a forward airfield in France in World War II – Quonset huts and all. When VIPs started visiting, which was almost immediately, things started to change dramatically. The local generals, Kelley and Swalm, could not stand the bare-base look at Tonopah. The maintenance men had to wear white coveralls, we had to have nice china to serve coffee and carpet in the hallway and all of the offices. We needed much larger hangars for the MiG-23s that we were told we would be receiving, and so the three little hangars housing our “17s” and “21s” were to be supplemented by two very large hangars that were probably two or three times larger.

While only at planning stage at this time, the addition of the MiG-23 hangars would also require that the small ramp (parking area in front of the three MiG-21 hangars) be extended as well, and all of this was going to draw attention from unwanted quarters, as was the engineering effort that was needed to level out the terrain to the north of the Red Eagles’ small pan and hangars. This situation was another planning issue to which Henderson had to focus his attentions: “Our ramp was kind of on a small bump, so before we could extend the ramp northwards, we needed to smooth the incline and descent to and from the pan so that we weren’t going to be taxiing the MiGs up and down a hill.”

Ellis was integral to the process and heavily involved throughout, as Henderson observed: “Bobby had boundless energy and always seemed to be working ten issues simultaneously. He was everywhere throughout the flying day – on the line watching and correcting crew chiefs if necessary, in the supply hangar helping design a parts stocking inventory system, in the fuel pit trying to figure out why our brand new POL tank was leaking, looking at blueprints for the new MiG-23 hangars to ensure the correct three-phase power was in the right location. It was mind-boggling the depth of knowledge he had on so many subjects.”

Keeping the Red Eagles “low profile” was becoming more of a challenge. “We were trying to blend in,” Henderson recalled, “but I had to ask myself, ‘Who are we fooling?’” The daily influx of military pilots into what was once a quiet DoE airfield, and the construction planned to start in 12 to 18 months, was something that the Soviets were likely to pick up on. At least the civilian-looking maintainers, who blended in while they stayed at Tonopah Monday through Thursday, were far less obvious.

Some maintenance challenges were too complex, or required specialist facilities to rectify, for the Red Eagle’s talented maintainers to address. One such task was the refurbishment of the MiG-21’s Tumansky turbojet engines, which were by now beginning to yield more of their secrets … like how many hours they were good for. “Most of the downtime we had on the jets was engine related – for an extended refurbishment after only 125–75 hours of engine running time, it took GE six months and a million bucks before they handed the engine back to us,” Henderson revealed. Ellis and his crew had fashioned a dolly for the engines, and transported them direct to GE on the 18-wheeler Kenworth, which was now painted fire engine red with gold eagle motifs on the doors, and christened “Big Red.”

The short engine life cycle was so expensive to fix that it sucked a huge proportion of what little funds remained in the 4477th TEF’s coffers, and left everything else having to be done on a shoe-string budget. One victim of this was the TX course, the USAF’s conversion course that transitioned experienced fighter pilots into a new or different aircraft. Although Oberle had been working on the course, and Morgenfeld and Iverson had started from scratch putting together limited manuals, Peck had not been in his job as the Red Eagles’ commander for long enough to truly formalize this process. So, while the squadron remained grounded awaiting the findings of the mishap report into Brown’s accident, Henderson looked to consolidate matters.

He started by reviewing the publications used by new pilots to learn how to fly the Soviet jets, and ordered that what currently amounted to hand-me-down notes and very basic written instructions took on a more structured format. He then looked closely at the TX course. “The problem was that we could not afford to give the new pilots a big spin-up on the jets. Every flight hour on these national assets was precious and we could only give them a few rides before they were expected to go up there and fly full air combat in the airplane.”

By the time Brown had arrived at the Red Eagles, the TX course had evolved significantly from the days of HAVE IDEA and even the earliest 4477th TEF operations of 1977, but by how much is a matter of contention. Oberle was adamant that “Hugh had gone through a checkout consisting of basic formation flying and aerobatics integrated into a syllabus of about nine or ten rides, each supervised and documented in grade sheets. Then he had flown controlled, graded, BFM flights against the T-38. Hugh was very aggressive and wanted to do well.” But Oberle is alone in this recollection, with most pilots of the time remembering that the course was substantially shorter – in the order of only five sorties. Indeed, a declassified list of CONSTANT PEG pilots (Appendix B) shows that Brown had been killed on only his ninth MiG-17 sortie with the unit, which contradicts Oberle’s assurance that the Navy pilot had received a checkout that consisted of nine or ten rides. And Peck deflected attention from the matter by stating that his recollection was that Brown came to the 4477th TEF already fully qualified to fly the MiG-17 by VX-4.

Henderson believes that the expedited TX course was possibly one of the things that killed Brown:

The MiG-17 can depart at high speed, and it’s a very violent out of control experience, but you’re still flying at 300 miles per hour. The stick was very high, so you’d go through the pebbles and the boulders – buffet that gives you indication that you maybe ought to let up on the stick – you had to put the stick forward to get all of the positive G-forces off the jet: only then would it recover. Brown departed like this, obviously not all that high, but only partially recovered. All of the pilots assigned to the 4477th were highly experienced aviators when they came on board and the checkout was kept to a minimum because of the aircraft being a limited, critical asset. I was one of those, and I checked out in the MiG-17 for a total of four or five rides. That number of rides to get checked out in a “new” aircraft, including air-to-air, is a very short syllabus. I had a lot of faith in the maintenance men to give me the best possible machine, but I would have been all thumbs in an emergency in that early phase.

The month that Brown was killed, the Red Eagles had hired a new pilot, who helped to document both the flying manuals and the TX course. He was a former Clark Aggressor who had been hired by Peck in July 1979, direct from the Philippines. It was Capt Mike “Scotty” Scott. Having spent almost four years as an Aggressor in the Philippines “I was slapping myself because I was doing the same thing, day-in, day-out. Sure, I had my family with me, I didn’t have to fly at night, and life was good.” But it was time for a change, and his time with the 26th TFTS was at an end. Scott had so impressed his superiors that they had offered him a choice of assignments. He could go and fly the F-15, the F-16, or return to Nellis as an IP at one of the Aggressor squadrons there.

In the end, the decision was made for him when, in the spring of 1979, he’d received a message via an old friend, Tom Hood, who had been his first flight commander when the Clark Aggressors were formed. “Tom told me that his old buddy from the 414th FWS, Gerry Huff, had been in touch to say that something was being formed and that he wanted me to apply for it.” Since Scott had worked for Huff in the Philippines, Huff was now sponsoring his application to the secret unit. The now-familiar catch was that he couldn’t say anything about the job. “Tom told to me to write a résumé, so I just wrote a two-page letter putting down my qualifications and saying that I was interested. I didn’t put it in a folder, or type it, I just put it in a letter and sent it to Tom Hood. Hood told me, ‘I’ll get this to Huffer.’”

Scott received orders to the 64th Aggressor Squadron at Nellis, arriving in the summer and reporting in to his new commander, LtCol Rich Graham. “But Richie Graham said to me: ‘You’re not going to be an Aggressor. I want you to walk down the street to a trailer house with a sign outside that says 4477th TEF, and go in there and ask for Gail Peck.’ I knew who Peck was because my squadron commander at Clark had told me who he was and had given me some idea of what he had been planning, just not the extent or where it was going.”

Scott had walked in to the trailer to the sight of Peck, Heatley, Oberle, and Morgenfeld fulfilling various administrative functions. Huff, the only man in the unit that he knew, was out of town. “Oh, it was exciting. And to be honest, it was an ego-fulfilling moment: I had been picked out of all these young captains that these guys had eyes on out here at Nellis, yet I had still been picked from Clark Air Base in the Philippines. It told me that people thought I had something to offer.” What Scott did not know was that this day would start for him an affiliation with the Red Eagles that lasted until the squadron finally closed its doors. From now on, he would be directly associated with the unit in one capacity or another for almost every day until its demise. He became “Bandit 14”16 in August, simultaneously becoming the first new Red Eagles pilot to go straight to the MiG-21.

Scott says that the decision to hire him is in part due to the fact that he had a current rating as an IP, FCF, and STAN/EVAL pilot on the T-38A and F-5E. The Red Eagles had borrowed one Aggressor T-38 for chase duties in the months before Peck’s departure,17 and on August 24, 1979, had been permanently loaned two Talons by the 49th TFW at Holloman. Scott could check out the other Red Eagles pilots on the T-38 if need be, and so too would McCloud, who later also qualified as a T-38 IP.

Prior to the arrival of the Holloman Talons, one or two Aggressor F-5s were flown up to TTR early each morning. Henderson said that the loaned T-38s were far more appropriate because the Aggressor squadrons didn’t like losing their F-5s to Tonopah each day. Plus, the two-seat T-38 finally allowed them to fly some photo chase sorties. The T-38s were swapped out with “new” examples at Holloman about every nine months, with basic maintenance on them being done on the ramp outside Base Operations at Nellis.

By October 31, Henderson had formalized and structured the CONSTANT PEG program to the satisfaction of the TAC commander. Until then, Scott said, “We had hand written or crudely typed ‘Dash 1’ pilots manuals. And the TX course had been written down, but the problem was that it wasn’t spelt out in ‘TACese’ – the language and format that TAC required.” Predictably, the formalization process changed nothing about how the unit operated, or how the pilots flew the MiGs, Scott added, but the important thing for TAC was that it now more closely conformed to its minimum standards.

Scott was vital to this process. His first job had been to put the program into “Air Force mode.” He worked hard to document formal manuals, and would actually spend the next four years on the squadron in overall charge of writing and refining manuals – a cyclical process that was never ending. The actual process involved several members of the squadron being given responsibility for a section of the manual, which was the best way forward given that the unit was somewhat undermanned at that time. Scott was also tasked with formalizing the T-38 checkout process, as well as securing the necessary TAC approvals to allow the Red Eagles’ pilots to be dual qualified in both the T-38 and the F-5. “We had to work some paperwork to get the T-38 and F-5 designated as the same airplane; that way we were effectively qualified in just one type.”

While the formalization appeased Creech somewhat, he had developed cold feet about the modus operandi of the Red Eagles, and Henderson was now left to fight the TAC commander for the survival of CONSTANT PEG in the format that Peck had originally envisioned only three years before. “Creech wanted the MiGs to be a simple, static flying tool that didn’t maneuver at all,” Henderson summarized. The earlier loss of Brown and his MiG-17 had given the TAC commander pause for thought, and the idea of another mishap was worrying enough for him to rein in the squadron’s flying program to mitigate the chances of that happening. “He told us: ‘You’re not out there to fight! The Soviets don’t fight that aggressively.’”

It was frustrating that TAC still had such a risk-averse attitude, but Scott believed there was more to it than met the eye. He had watched the Aggressors start conservatively in the early 1970s, before gradually increasing the complexity of the training and the sophistication of the scenarios. Then it all changed. In 1977 the Air Force and Navy jointly ran the Air Intercept Missile Evaluation (AIMVAL) and Air Combat Evaluations (ACEVAL) tests against Navy F-14s and Air Force F-15s to develop tactics and the next generation of weapons, a program on which Drabant had been an analyst. Over the course of more than 2,300 sorties, tactics and other factors were evaluated by Aggressor pilots and Navy adversary pilots flying Red Air F-5Es against Blue Air F-15s and F-14s. The evaluations provided some great data, but they brought out the worst in the “Type A” personalities on both sides. By the end of the evaluation, trickery and underhanded techniques were being used to help win an engagement at any cost. It went against everything the Aggressors stood for.

“This type of attitude was starting to become more common within Aggressors by this time, and they therefore developed a reputation for winning at all costs as opposed to training other fighter pilots to improve,” Scott said. The Aggressors’ mantra, “Be humble, you cool fucker,” was going out of the window, and Creech knew it. “He did not want this attitude to spill over into the Red Eagles. Hence his keenness to keep our exposures simple, with very scripted profiles. In Creech’s view, our program was going to be a training mission, but one that operated in a scripted, exposure mode.”

One month later, on the night of Halloween, Henderson returned to Langley to sell Creech on the changes that would keep CONSTANT PEG viable. “There was not a lot I could change, but I was following Heatley’s suggestion and working with the Navy on getting a spin orientation program started up. One of the real hang-ups about the MiG-17 mishap was that Hugh had departed the airplane on a previous mission, but he had not reported it adequately. So I introduced a very formal and structured manner of reporting spins and departures: you had to immediately report it.”

Creech was satisfied with what he saw, and Henderson left the meeting having managed to reach something of a compromise with the general. Scott recalled that one was a limitation that prohibited the Red Eagle pilot from turning the MiG through more than 360 degrees before calling “Knock it off!”, the radio transmission that terminated the fight. It was not ideal, but it was much better than flying around in gentle turns as Creech had earlier suggested.

There was no immediate effort made to replace Brown’s MiG-17. Patty 002 had some history – it was actually HAVE FERRY, and had been flown by America since 1969. For now, the Red Eagles made do with just one Fresco, but another MiG-17F would arrive within a year.

The Fresco was an amazing little aircraft. Throughout the 255 sorties that HAVE DRILL flew in 1969, it experienced not a single mechanical fault that would cause it to be removed from the flying schedule. As with the MiG-21, its construction was sturdy yet simple, and it featured some very basic systems that made it less likely to fail in the air. And when there were maintenance issues, Henderson divulged, there was a massive stockpile of spares available for the Fresco, certainly far more than was the case for the Fishbed. Ignoring the upkeep and refurbishment of the VK-1F engine, keeping the MiG-17 airworthy was quite straightforward.

Back in 1949, the Mikoyan-Gurevich (MiG) design bureau had been ordered to create a successor to its highly successful MiG-15 “Faggot.” MiG retained the basic design of the Faggot, but added a wing with a 45-degree sweep instead of the original 35 degrees, and stretched the fuselage by 3ft. The vertical tail was also enlarged. Two pre-production aircraft were built and flown in 1951, and the new fighter was designated the MiG-17. By 1952, the first production machines – featuring larger airbrakes, an updated avionics suite, and an electrical engine self-starting system – were rolling off the production lines.

The MiG-17 soon entered service with the Voenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS), the Red Air Force, and was given the NATO codename “Fresco.” The MiG-17 was small by anyone’s standards: its vertical tail was only 12ft tall, and its wings spanned just 32ft. From nose to tail, the Fresco was just 37ft long.

The version of the MiG-17 acquired by America from Israel was the re-engined MiG-17F, Fresco C. It boasted the VK-1F engine, which was a copy of the British Rolls-Royce Nene and offered just under 7,500lb of thrust. The aircraft had an empty weight of 8,646lb, and its afterburner improved climb performance if not acceleration and maximum speed, the latter of which was placarded (officially limited) at 700 miles per hour at 10,000ft. The 1952 C-model Fresco featured a number of small improvements over the original MiG-17, including an SRD-1 radar gunsight and a revised fuel system. Externally, it was distinct from the previous model in having bigger speed brakes, a revised exhaust nozzle to cater for the afterburner of the F-model of the VK-1, and a rear-view mirror mounted on the canopy.

The most immediate and obvious difference between the MiG-17 and American jet fighters became apparent before even taking off. When it came to taxiing, Henderson explained, “They had a totally different way of doing it. They used air pressure, applied by a lever on the stick grip to the brakes. You squeezed the lever and then you moved the rudder pedal differentially to steer the aircraft. It was not a natural act! We dedicated an entire TX ride to taxiing – start engines, taxi down the taxi way, and then come back.” The MiG-21 used exactly the same system.

Oberle expounded further:

Taxiing the airplanes was a bit of a trick. If you wanted to turn right, you pushed the left rudder bar in and you pulsed this lever on the control stick. That dumped the pneumatic pressure to the brake on the left wheel and transferred it to the right wheel. You would get the free-swinging nose wheel to start to turn to the right, and then as you got ready to come out of that turn you’d have to push the left rudder bar past neutral and you’d have to start pumping the little paddle again to get the power back on the left wheel, to get the nose to straighten out so you could taxi straight! It was like a snake taxiing out down the taxiway until you got more familiar with it. Once you learned it, you could taxi fairly comfortably.

Henderson said the MiG-17 was easy to fly for the most part, but reminded him of an old tractor. “It had bumps and crap all over the exterior surface. It was crude. The cockpit visibility was terrible and the cockpit had valves – faucets, literally – to turn things on and off.” Oberle agreed completely: “It was designed by an apprentice plumber to be flown by an Orangutan. There were hydraulic, oil, and pneumatic valves running through the cockpit that you had to reach around behind your elbow to operate during various emergency procedures.”

Henderson’s first attempt at starting the MiG-17s VK-1F engine had resulted in a false start. “After the first start attempt, I had inadvertently left one valve open so that fuel was continuing to pour into the tailpipe. When I started the engine a second time there was a huge fireball that came out of the tailpipe. That spectacular sight was pretty interesting to see, and I was impressing the hell out of my maintenance guys! They must have been thinking, ‘Oh my God. Is this our commander?’”

The VK-1F was slow to respond to movements of the throttle, and it took in the region of 15 seconds for it to go from idle thrust to “military” thrust power setting (the maximum non-afterburning thrust available). Oberle observed: “This slow engine response was a characteristic of the old engines. If you kept the power up above 80 percent you had pretty good engine response, but if you ever pulled it back to idle and then pushed the power up to accelerate, it would take forever for the engine to spool back up to the 80 percent range where you finally started getting power. My technique was I never went below 80 percent. If I needed more deceleration I kept at 80 percent and put speed brakes out; I wasn’t sitting there waiting for the engine to spool up.”

Peck noted that the elevator trim switch – used to keep the aircraft flying straight and level as airspeed changed – was located not on the stick as was traditional in contemporary US aircraft, but took the form of a wheel mounted on the cockpit side below the canopy rail; an antiquated approach that dated the Fresco and had long since been superseded in Western fighters. “There were also no landing gear indicators in the cockpit of either MiG, and so when the gear came down a little barber pole stuck up on the upper surface of the wing and on the nose of the fuselage forward of the cockpit.”

Adding to the Fresco pilot’s woes, its ejection seat could not be adjusted in height, so it became an important life support issue to go out to the jet and be measured for seat pads that positioned the pilot at the optimum sitting height. “People protected their pads carefully,” Peck said candidly, “because everyone has a slightly different seating position and you didn’t want to be too low or too high.” Too low and visibility from the cockpit was further restricted, and too high and pilot’s head rattled against the canopy and periscope. Further, the pilot could be knocked unconscious, or worse, killed during ejection.

A young Capt Earl Henderson cradles his flight helmet prior to a sortie over North Vietnam. Henderson would go on complete his ‘100 Missions North’ in the F-105, earning six Distinguished Flying Crosses and a Silver Star in the process. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

LtCol Fred Cuthill, of AFSC, straps into the HAVE DOUGHNUT MiG-21 at Groom Lake in 1969 with the assistance of TAC pilot Maj Jerry Larsen. At the time, Larsen was assigned to the 1137th Special Activities Squadron, based at the Pentagon. (US DoD)

Lt Bob “Kobe” Mayo poses before a combat mission over Vietnam in his F-100 Super Sabre in 1969. Mayo would eventually become a TAC HAVE IDEA pilot. (Kobe Mayo via Steve Davies)

Maj Ed Clements had flown the F-100 Super Sabre in Vietnam, and would go on to become one of the initial cadre of the F-15 FWIC. He was allotted a single HAVE IDEA sortie in the MiG-17. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

LtCol Lloyd “Boots” Boothby, the father of the Aggressors, photographed in the summer of 1972 while he headed up the Red Baron reports. (Joyce Boothby via Earl Henderson)

Maj David “DL” Smith photographed at Nellis AFB in 1974 during his time with the 64th FWS. Smith, who had made a name for himself in Vietnam, became one of the first three TAC HAVE IDEA pilots, and was instrumental in the creation of CONSTANT PEG. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

Maj Joe Lee Burns, who had successfully ejected from a crippled F-4 Phantom off the coast of Vietnam, was one of the first pilots selected by TAC to fly MiGs as part of HAVE IDEA. This close-up, dating to 1974, was extracted from the 64th FWS squadron group photo. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

Maj Alvin “Devil” Muller photographed in 1974 during his stint with the 64th FWS. At this time, Muller was secretly flying the HAVE IDEA MiGs, and would eventually join the 4477th TEF where he would become responsible for planning the security arrangements surrounding CONSTANT PEG. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

The 64th FWS Aggressors of 1974 photographed in front of a T-38 Talon. Those who went on to be Red Eagles or flew the HAVE IDEA MiGs are: Back row, left to right – Mike Press, Earl Henderson, and (fifth along) Ed Clements; Front row, left to right – (fourth along) DL Smith, Gene Jackson, and (far right) Joe Lee Burns. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

64th FWS Aggressor Maj Ronald Iverson in 1978. This photo was taken at around the same time that he was secretly heading the Foreign Military Exploitation of the ex-Egyptian Air Force MiG-23 Floggers under codename HAVE PAD. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

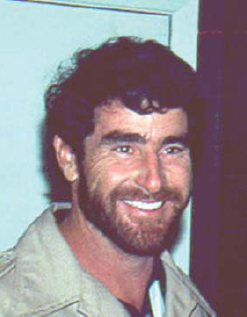

Maj Dave “Marshall” McCloud, complete with beard, following a successful TDY to collect MiG parts “in a foreign country” in December 1979. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Master Sergeant Robert “Bobby” Ellis at the Mizpah Hotel Bar in spring 1979. Ellis, who was also known as “Daddy,” always sported a buzz cut hairstyle. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

LtCol Earl “Obi Wan” Henderson, the ops officer for the 64th FWS Aggressors, photographed in the summer of 1979. Months later he would become the third commander of the Red Eagles. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

From left to right: Maj Gerry “Huffer” Huff; Dell Gaulker, REECo’s construction manager responsible for Tonopah; and LtCol Gail “Evil” Peck, the incoming 4477th TEF commander, at the Mizpah Hotel Bar in the spring of 1979. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Maj Phil “Hound Dog” White, ops officer of 65th FWS Aggressors in 1979. White took command of the 4477th TES in August 1984. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

LtCol Earl Henderson hosts a party at the Mizpah Hotel Bar, Tonopah, in spring 1980. From left to right: Bill McHenry, a MiG-17 crew chief; Henderson; and Tommy Karnes, a MiG-21 crew chief. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

LtCol Joe “Jose” Oberle sits in the cockpit of his F-16 Viper in the fall of 1980. So secret was CONSTANT PEG at the time that Oberle’s squadron commander had no idea that his new pilot had come from a tour flying MiGs. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

LtCol Joe “Jose” Oberle holds a falcon bird of prey – the namesake of the Air Force’s official title for the F-16 – at McDill AFB in 1980. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

Maj Karl “Harpo” Whittenberg, “Bandit 11,” relaxes beer in hand at one of Henderson’s frequent parties in 1980. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Maj Chuck “Chuckles” Corder in relaxed surroundings in 1980. Corder became a well-respected operations officer for the Red Eagles. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

LtCdr Tom Morgenfeld, photographed in the spring of 1980 just prior to his retirement from the Navy, had first flown the HAVE IDEA MiGs with VX-4 at Point Mugu. He was hired by the 4477th TEF to teach new pilots to fly the MiG-21. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

With the aid of Henderson’s swimming pool and some willing volunteers, LtCol Tom Gibbs undergoes recurrency training in water survival in July 1980 prior to taking command of the 4477th TES from Henderson. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

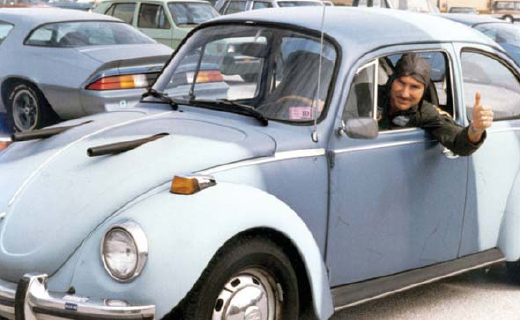

Maj Joe “Jose” Oberle in his Volkswagen Beetle: “Glenn Frick and I acquired two used 20mm gun barrels, cut holes in the hood and then welded the barrels in. We then painted it to look like an Aggressor F-5, and I drove this around Las Vegas during my time in CONSTANT PEG.” (Joe Oberle via Steve Davies)

Ike Crawley, a Red Eagles engine maintainer, and Ralph Payne, one of Tonopah’s small cadre of firemen. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

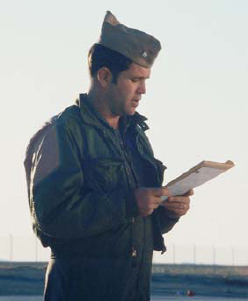

LtCdr Keith Shean reads an announcement outside the MiG hangars at Tonopah. Shean acquired the call sign “Soxs” because he never wore any. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Maj Mike “Bat” Press and LtCol Joe “Jose” Oberle swap “There I Was” stories in June 1980. Press had been secretly flying MiGs in the US and abroad for many years before he joined the 4477th TES. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

LtCol Tom Gibbs, life vest inflated, completes his refresher water survival training in Henderson’s pool. He has been tethered to a rope and dragged through the water to simulate being dragged along by his parachute. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

The 4477th TES maintainers, resplendent in white coveralls and red and white Red Eagles baseball caps, stand at ease on Tonopah’s ramp under the watchful eye of Maj Chuck Corder (looking back). The occasion was the change of command ceremony between Henderson and Gibbs in summer 1980. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

Lenny Bucko took on the role of events organizer upon being selected to join the 4477th TES. A Marine aviator with a passion for scuba diving and water sports, he is seen here in the middle of the back row following a white water rafting trip. Chuck Corder is in the blue tee-shirt to the far right, and Burt Myers is second from left in the yellow tee-shirt. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

Photographed in front of the MiG hangars at Tonopah; (left to right) Myers, Corder, Bucko, Postai, Scott, (bottom row) Laughter, and Green receive their cash advances for expenses prior to setting off to Houston, Texas, to qualify for their FAA multi-engine rating. As is clear, the men approached the trip with deadly seriousness. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

LtCol Earl Henderson (left) salutes incoming commander, Lt Col Tom Gibbs, at Tonopah during the June 1980 handover ceremony. Henderson’s flying career had been cut short by the discovery of heart disease during a routine flight physical examination. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

LtCol Earl “Obi Wan” Henderson and Captain Herbert “Hawk” Carlisle during an intelligence-gathering trip to East Berlin in 1988. Carlisle had not long before ejected from an out-of-control MiG-23 over the Tonopah Test Range. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Maj Rick “Caz” Cazessus photographed in around 1990 as a 64th FWS Aggressor pilot. Cazessus went to the Aggressors following the shut down of the 4477th TES in 1988. (USAF via Earl Henderson)

Lloyd “Boots” Boothby and Randy O’Neill talk during the 1992 Aggressor reunion at Nellis AFB. O’Neill, who had deep-rooted black world contacts, is widely regarded as the driving force behind HAVE IDEA. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Col Glenn “Pappy” Frick during the 1992 Aggressor reunion at Nellis. Frick was the Red Eagles’ first commander. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Earl Henderson (left) and Chuck Holden at the Nellis Officers’ Club, Nellis AFB, in January 2008. Holden had flown Frick, Oberle, and Peck around during the search for an operating location for CONSTANT PEG. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Commonly referred to as “the HAVE DOUGHNUT article” by those involved in its exploitation, the MIG-21F-13 is seen here having test instrumentation installed inside a hangar at Groom Lake in 1968. (US DoD)

HAVE DOUGHNUT was flown only by US Navy and US Air Force Systems Command pilots during its 1968 exploitation (one of whom, LtCol Joe Jordan, was seconded to TAC for the evaluation). Only later would TAC pilots be allowed to take the controls. (US DoD)

HAVE FERRY was the second of the two MiG-17F Frescos loaned to the United States by Israel in 1969. It was this exact aircraft, 002, in which Navy LtCdr Hugh “Bandit” Brown would lose his life in August 1979. (US DoD)

HAVE DRILL was used for the majority of the early MiG-17 exploitations, while HAVE FERRY acted as a spare. (US DoD)

An unidentified Red Eagle marks the small cabin used initially by the 4477th TEF as its operations room in 1979. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The MiG-21 cockpit was a jumbled assortment of switches and dials, and was quite confined by the standard of most Western fighters. In later years, English placards were eventually added by the ever-resourceful Red Eagles maintainers to help the pilots in their cockpit checks. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The charter members of the 4477th TEF maintenance contingent show off their new 18-wheel Kenworth truck. Ellis (far left) used the truck to transport secret shipments of MiG parts and spares around the country. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

One of the first challenges a US MiG pilot had to master was the pneumatic braking system, activated via a lever on the stick (seen here being demonstrated by a 4477th TES pilot sitting in a MiG-21F-13). (USAF via Steve Davies)

A still image, taken from a long-list movie reel, of a MiG-17F Fresco C taxiing back to the newly laid ramp at Tonopah. The date is probably late 1979. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The view ahead in the MiG-21 was marred by a large 8mm gun camera (right), and various other instruments. Some aircraft featured printed checklists below the gunsight, as in the case of this 4477th TES MiG-21F-13. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The antiquated and industrial nature of the Fresco’s systems and cockpits made for a different set of cockpit tasks than most of the Red Eagles were used to. Oberle elucidated: “When you took off, you raised the landing gear handle until the gear came up and locked, and then you had to put the gear handle back in the neutral position to take the pressure off of the top of the gear, otherwise you kept the hydraulic system running. Putting it to neutral turned it off until you were ready to come back and land.”

Oberle had one particularly serious In Flight Emergency (IFE) in the Fresco:

I had an IFE on take-off. We had wing tanks on it because we were trying to get longer sorties on it. I am rolling down the runway, and as I lift off the afterburner blows out. I was too fast and too far down the runway to catch the rabbit catcher, so I called mobile control and asked them to drop the barricade. I had flying speed, but barely lifted off by the end of the runway. I had to leave the gear and flaps down as it continued to accelerate against the rising terrain. As it eventually did that, I raised the gear and flaps and milked as much out of it as I could.

He made it, but it was a close thing. “It was one of those situations where you had to decide on whether to take the barricade, or to rely on your skills. Relying on my skills paid off.”

“The MiG-17 was so forgiving in the landing pattern,” Oberle continued:

You could flare and hold it off until you gently greased the wheels onto the runway. The -17 was not too different from the Air Force’s T-37B Tweet: it could flare and you could hold it off. You always had the speed brakes out when you landed. The technique would be to come in, put the gear and the flaps down coming off the base turn. You pulled the power back until you got slowed down, then you kept the power up in the 80 percent range as you came in on finals to land. When the landing was assured, and by that I mean you’ve come in over the runway overrun area and you know you’re not going to go around, you could go ahead and close the throttle off to idle and flare until it touched down. On finals, you could keep the power in 80 percent range and modulate speed brakes to keep it the speed where you wanted it. Then, if you needed to go around, you closed the speed brakes, increased the power, raised your nose for the climb out, and raised the gear and flaps.

Since the VK-1F centrifugal compressor engine generated only 6,000lb of thrust without afterburner, and the Fresco C had a fighting weight of just under 12,000lb, the motor’s RPM gauge was one instrument that everybody got to know well. In fact, the MiG-17 did not have a nozzle position indicator to inform the pilot that the afterburner had lit, and instead he relied on a peanut-sized boost gauge that indicated whether the raw fuel pouring into the exhaust nozzle had lit off. Such indications were normally felt by a push in the back as the augmentation kicked into life, but the Fresco was underpowered enough that the additional thrust of its afterburner was imperceptible. Because the fuel fraction in the MiG-17 was so small, the Red Eagles flew their Frescos with external wing fuel tanks that increased their sortie duration, but added more aerodynamic drag. That made them even “sportier” on take-off.

As part of Henderson’s formalization of the TX course, one of the first rides required the student to depart the aircraft deliberately from controlled flight so that the spin characteristics, and more importantly, recovery technique, could be experienced and practiced under a controlled and safe environment. Oberle explained the feedback that the MiG-17 gave the pilot as he demanded a tighter and tighter turn or pitch-up: “If you were loading it up with Gs you’d begin to get an onset buffet. This told you that you were losing some lift and approaching an accelerated stall. If you pulled in a little tighter the airplane would begin to wing rock a bit, which was telling you were getting into an accelerated stall. If you continued to pull through those characteristics it would snap roll on you, very violently so you’d bang your head on the canopy. It was as well to have a helmet on, otherwise you would be dazed.”