BELIEF IN THE POWER OF EDUCATION is a deeply rooted American value. Thomas Jefferson held that the “diffusion of knowledge among the people” was crucial to the American experiment. “No other sure foundation can be devised, for the preservation of freedom and happiness,” he wrote.[267]

Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers emphasized the importance of skills like reading, writing, and calculating, as well as knowledge of subjects like history, geography, and science. They designed this country to be a place where a free people can use what they learn to make good, prosperous lives.

The founders knew that academics aren’t all there is to education. Jefferson wrote that good schooling involves the improvement of one’s “morals and faculties.” That is, good schools teach character. They help students learn virtues like honesty, dedication, and respect.

The founders also understood that schools should help students learn the values, knowledge, and skills they need to become responsible Americans. The objects of education, Jefferson wrote, are “to instruct the mass of our citizens in . . . their rights, interests and duties, as men and citizens.”[268] Good schools help make citizens who love their country, know about democratic ideals, and are not afraid to stand up for them. Otherwise, the American republic cannot survive.

Just about everyone has an opinion about education issues. That’s partly because everyone has experience with school, either public school, private school, religious school, or home school. We’ve all run into great and not-so-great teachers, textbooks, and classes. We’ve formed ideas, based on firsthand knowledge, about what can be good and bad about an education.

We all have an ownership in American education, even after we graduate. Many of us have children or grandchildren who are in school, or we will someday. The health of our communities, our economy, and our whole country depends on our schools. Even the property values of our homes are tied to the reputation of nearby schools.

Given all this, it’s easy to understand why education issues are often debated with passion. They should be. There is a lot at stake, and there is much work to be done.

Does America do a good job educating its students?

It would be a wonderful thing if most children in this great nation received great educations. Unfortunately, they don’t.

- More than half of high school seniors taking the ACT or SAT don’t have the skills they need to succeed in college.[269]

- According to national tests, about six in ten high school seniors can’t read well. Three out of four seniors can’t do math as well as they should.[270]

- On international tests, American fifteen-year-olds score below average in math, ranking behind many other countries, such as Japan, Korea, France, Poland, and Latvia. American students score only average in science and reading compared to other countries.[271]

The American education system faces serious, complex problems. If things don’t improve, it could mean a dimmer future for the United States. Good jobs require good educations, and people who can barely read and write face a lifetime of financial struggle. The nation as a whole can’t prosper as it has if other countries’ citizens know more and can do more than we can.

Americans recognize this and have been trying to improve schools for more than three decades, with limited success. As the numbers above show, we have a long way to go.

Why is K–12 education in America mediocre?

Part of the problem—a big part, in fact—lies not with our schools but with events and trends taking place in our culture. The greatest threat to education is the breakdown of the American family. When large numbers of children grow up without fathers, or in households where single parents struggle to get through the day, or in households where adults aren’t paying attention to their kids, schools feel it.

If you ask teachers what would most improve American education, you hear one answer over and over. They say, “We need more parental involvement.”

You’ve likely been in classrooms where teachers have to deal with students who don’t know how to behave because there is no one at home to teach them good habits. Or students who don’t turn in homework because no one checked to make sure it was done. The less discipline and help kids get at home, the harder it is for schools to teach those students.

Another problem is all the distractions outside the classroom. American teens spend more than seven and a half hours a day watching TV, listening to music, social networking, surfing the web, and playing video games.[272] That compares to less than an hour a day doing homework.[273] Those numbers alone go a long way toward explaining things.

This isn’t to say that schools are blameless. Too many have low academic standards. They set low expectations for students, and students learn to get by with little effort. Textbooks, tests, and assignments are watered down. Teachers let students make posters or draw pictures instead of writing papers.

In Japan, if a student doesn’t do well in math, the answer is to do more math and work harder at it. Too often in America, students get away with saying, “My brain’s just not that good at math. My grandfather wasn’t good at math, my Aunt Gladys wasn’t good at it—math just doesn’t run in my family.” The result: Japanese students are much better at math than American students.

Some schools don’t focus enough on basic subjects. Students spend a lot of time learning to respect the environment but not so much time studying history. It comes as no surprise, then, when those students graduate without knowing what century the Civil War was fought in.

Won’t spending more money on schools fix things?

“We need to pay teachers a lot more if we want better schools.” “We need more computers in classrooms.” “If Washington would spend more money on schools instead of tanks and missiles, education would be a lot better.”

It’s easy to think that if we just dumped more money into the system, things would improve. But we’ve learned in the last several decades that money alone is not the answer. More dollars do not guarantee better schools. Some schools spend a lot of money and get poor results. Other schools with fewer resources give children a fine education.

As a society, we invest enormous sums in education, and expenditures keep climbing. The United States spends an average of $13,500 per year on each public school student.[274] That’s far more than most other countries spend.[275]

Most money spent on public schools comes from local and state taxes. Federal funds from Washington, DC, supply roughly one out of every ten dollars spent on education up through high school.[276]

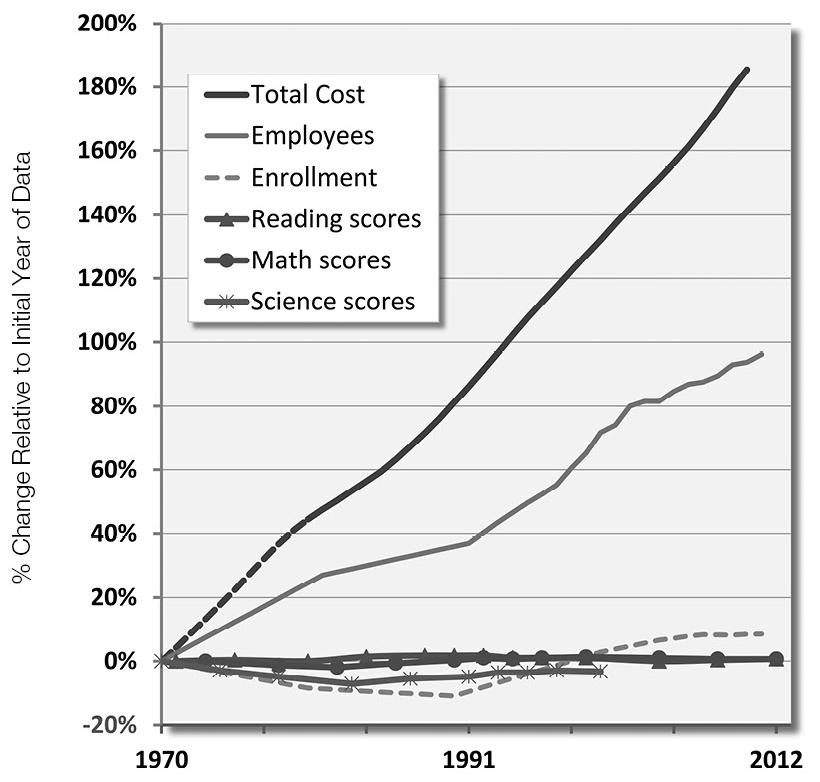

As the graph below shows, since 1970 America has poured more and more money into educating students. Yet during that same period, test results have remained mostly flat.[277]

Good education is largely about effort and focusing on things that matter. Spending more money on schools won’t help unless other changes happen.

Trends in Public Schooling since 1970

“Total cost” is the full amount spent on the K-through-12 education of a student graduating in the given year, adjusted for inflation.

In 1970: $56,903

In 2010: $164,426

Data sources: U.S. Dept. of Ed., “Digest of Education Statistics,” & NAEP tests, Long Term Trends, 17-year-olds.

Graph courtesy of the Cato Institute

Can’t Washington fix schools for us?

There is an old story about the Greek mathematician Euclid, who taught geometry around 300 BC in Alexandria, Egypt. King Ptolemy heard of his fabulous calculations and asked for some instruction. Euclid started to explain some basic theorems, but the king soon interrupted. “I have little time,” he said. “Is there no easier road to the mastery of this subject?” Euclid gently replied, “Sire, there is no royal road to geometry.”

As in math, there is no royal road to education reform. There are no quick or easy answers. It’s especially hard to fix American schools from Washington, DC.

Think about a class you took that wasn’t particularly good. Maybe there were disruptive students in the room or an uninspiring teacher or a boring textbook. Whatever the problem, there is no lever a senator can pull or button the president can push to fix that class. Washington, DC, is simply too far removed.

Washington has tried. In 2001, during the administration of President George W. Bush, Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act to improve student achievement. In 2009 President Barack Obama launched a program called Race to the Top to encourage reform. Between the two programs we’ve spent billions of dollars. It’s hard to see that education has improved much, if at all.

Generally speaking, schools work best when local communities are in charge of them—not bureaucrats in faraway places. People who live near a particular school, who send their children there and see what kind of students it produces, know best what that school needs. A school in Boston might have very different problems from a school in Omaha or Los Angeles. That’s why Americans have left most education decisions in the hands of local and state officials, not the federal government in Washington.

Fixing education is mostly a bottom-up, school-by-school process. It starts with parents, teachers, and principals, and it takes the dedication of whole communities.

What makes schools get better?

Here are ten basic principles of education reform that conservatives adhere to:

- Parents are the first and most important teachers. Their efforts and expectations make all the difference. The more involved they are, the better their children’s chances of getting a good education. When they remove themselves from the learning process, those chances plummet. Schools can’t function well without parents’ help. They can’t replace the care a parent can offer.

- Schools have to set high expectations for all students. Here the old saying “Aim high” applies. Schools that maintain high standards get higher achievement from students. Schools that offer dumbed-down lessons and slipshod standards get little in return.

Not all students have the same abilities, of course, so teachers must adapt lessons to appropriate levels. But all students should be challenged and expected to meet solid standards. Requiring any less is selling young people short.

- Schools must be safe and orderly places. Discipline and academic success go hand in hand. Where there is chaos, little learning occurs. In good schools the rules are clear—and enforced. The teacher is the moral authority in the classroom, with the responsibility to tell students how to behave. Parents and school officials back teachers up and make it clear to students that they must respect teachers’ authority.

- Schools should focus, above all, on academics. Good schools are temples of learning. They present a clear, specific curriculum that states what students are expected to learn each year. That curriculum attends to the basics: English, history, math, science, and the arts. Most of the day is devoted to these core subjects. Good schools don’t clutter the curriculum with so many other topics that the basics get pushed aside. They concentrate on essential skills: reading, writing, and speaking English well; analyzing and solving problems; thinking clearly and precisely.

- Schools must help parents develop good character in students. As the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. reminded us, “We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.”[278] Good schools teach about right and wrong. They help young people acquire virtues such as self-discipline, diligence, perseverance, and honesty. Teachers cultivate these traits largely by helping students form good habits: getting to class on time, being thorough about assignments, speaking respectfully to others.

- Knowledge is as important as skills. Some schools are big on teaching “critical thinking” but not on mastering factual knowledge. They view memorizing facts as old-fashioned. But knowledge—knowing things—makes you smarter. You can’t do much critical thinking about any topic without first knowing some things about it. There are some facts and ideas that all American students should know: what a right triangle is, where the Mississippi River is, what happened in 1776. Good schools have a clear vision of the knowledge they want to transmit.

- Good schools teach civic virtues. They help students learn to be responsible citizens. They help them learn to respect others and live up to obligations. They offer a good dose of American history, including events that tie us together as a people: the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, the March on Washington in 1963. They teach the central principles that underlie American democracy. They acquaint students with their rights as well as their duties to this country.

- Schools should be held accountable for results. They should be judged by how much their students learn. For a long time, public schools resisted the idea of making sure that students meet certain standards. In recent years states have tried to correct this problem by coming up with standards in different subjects that schools must follow. The reform has been more successful in some places than others. There is still work to be done. But overall, it makes good sense that schools spell out exactly what they will teach students and then be held accountable for meeting those goals.

- Good teachers should be rewarded. Bad teachers should be given the opportunity to improve. If they don’t get better, they should be dismissed. Most teachers are capable, dedicated professionals. But there are bad teachers as well. If you’ve had one, you’ve probably wondered, Why don’t they get rid of someone this bad?

Unions such as the National Education Association have made it extremely difficult for principals to get those teachers out of classrooms. Sometimes it can take years of jumping through bureaucratic hoops. That’s because the unions want to protect jobs. But putting jobs ahead of students’ educations is wrong. In most professions, good work gets you rewarded, and bad work gets you a pink slip. Many schools would be better places with that approach.

- Families should have the right to choose the schools their children attend. In many places, the public school system assigns children to schools. This helps ensure that schools have a mix of students with different races and backgrounds, which is good. But there are downsides. Students sometimes get assigned to bad schools or schools that don’t fit them well. That’s wrong.

Wealthy families get to choose their schools either by purchasing houses in neighborhoods with good public schools or by paying for good private schooling. Poor children, however, often find themselves trapped in bad schools. Many places have been offering more school choice in recent years, which is a good development. If parents are unhappy with a school, they should be able to take their children elsewhere.

Are some things more important to learn than others?

Conservatives believe that schools should transmit knowledge of important ideas, works, and principles from one generation to the next. Students should be exposed to great works of literature like Hamlet and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. They should know what the First Amendment means and what happened on D-Day. They should see images of great works of art like the Mona Lisa and hear great compositions like Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5.

Such things are part of the culture all Americans have inherited—the “common culture,” as it is sometimes called. These things are part of the glue that holds us together as a people. They help tell us who we are.

Most educators agree that it’s important to teach about our common culture, but many schools do a poor job of it. For example, only about one in ten American high school seniors has a solid grasp of American history.[279] That goes a long way toward explaining why most American adults have a hard time answering questions like “What are the three branches of the US government?”[280]

Who decides what is most important to teach? Sometimes there are disagreements about particulars, but for the most part, it is a matter of consensus. Time is often the judge. The works of Socrates and Michelangelo, for example, have stood the test of time.

It is not a good idea for the federal government to dictate what American students should learn, for two reasons. First, if Washington was in charge, scores of different groups would lobby to influence the curriculum, and the result would most likely be a political mess. Second, there would be a terrible temptation for the federal government to influence people’s lives by controlling what they learn. Far better to leave curricula up to the wisdom of parents, teachers, communities, and states across the country.