2

Downtown Development and the Endeavors of Filmmaker Kent Mackenzie

We were fascinated by this complex and rapidly changing life we saw around us and felt it was our duty to examine it.

—FILMMAKER KENT MACKENZIE, 19641

Making the cover of the spring 1962 “Hollywood” issue of Film Quarterly gave the acclaimed documentary The Exiles (1961) and its creator Kent Mackenzie substantial visibility and renown.2 Taken from the film’s title and closing image, the journal’s cover features an extreme long shot of a small group of American Indians in early-morning Bunker Hill. Framed by the Sunshine Apartments to the right and the Angels Flight funicular railway above and in front of them, they walk down Clay Street. Their previous night in downtown Los Angeles began in a clapboard apartment on the same block before moving to the bars on Main Street, then on to Hill X overlooking Chavez Ravine (soon to be Dodger Stadium), and then back to their respective homes. Film Quarterly’s decision to highlight an experimental documentary made by a white liberal filmmaker about the daily lives of minority Angelenos in a working-class part of the city was not as strange as it might initially seem. Besides the fact that Mackenzie’s former mentor at USC, Andries Deinum, served as an advisor to the publication, Film Quarterly had always been a forum where a wide spectrum of cinema was discussed. Throughout the journal’s previous iterations it had remained dedicated to examining film and television in Los Angeles and how filmmakers struggled to express themselves from within, draw on the resources of, and attempt to separate themselves from mainstream Hollywood. Interviews with directors, reviews of new technology, and essays on contemporary films exposed readers to recent trends in American moviemaking as well as global New Wave cinema and festivals.3 In this issue journalist Benjamin Jackson praised The Exiles in a review and Mackenzie himself participated in a roundtable discussion titled “Personal Creation in Hollywood: Can It Be Done?”

FIGURE 5: Cover, Film Quarterly 15, no. 3 (Spring 1962). Courtesy of University of California Press.

Filmmaker Thom Andersen’s excavation of Hollywood’s selective memory of its home metropolis, Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), gave special notice to The Exiles as representing what was often hidden or obscured from view in studio-created fiction. Andersen sees the film as a testament to the more human-scale and walkable city that preceded downtown’s flashy hotels, office buildings, and parking lots: “Better than any other movie, it proves that there once was a city here, before they tore it down and built a simulacrum.” Andersen would later write in Film Comment that “The Exiles is the most concrete and detailed record we have of these doomed spaces.”4 Los Angeles Plays Itself helped put Mackenzie’s documentary on the radar of scholars, preservationists, and cinephiles. In 2008 Milestone Films, USC, and UCLA joined forces to restore The Exiles. It was rereleased in theaters that same year, and was selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2009. As a result, The Exiles has found enthusiastic audiences within and beyond the academy. Despite this second life, however, little attention has been paid to the cultural context in which it emerged and the project’s relationship to Mackenzie’s other filmmaking endeavors.

Like Mackenzie’s student documentary on elderly pensioners in Bunker Hill, The Exiles countered popular understandings of the area’s social identity and defied urban planners’ vision of a lucrative downtown. The Exiles demonstrated that downtown was not simply a blighted landscape in need of sweeping demolition and redevelopment, but a populated area in which marginalized communities lived. The film also challenged the lofty tenets of President John F. Kennedy’s “New Frontier” platform by engaging with the conflicted legacy of America’s old frontier mythology. Showing American Indians’ daily routines critiqued the stereotypes of them as historical peoples of the past who were no longer part of the national polity, or as a victimized people of the present, suffering in impoverished reservations and urban slums.

Mackenzie brought great passion to the project, but its construction was nonetheless arduous. In the same Film Quarterly issue that featured The Exiles on the cover, he expressed his frustrations during the roundtable led by the journal’s Los Angeles editor and UCLA professor Colin Young and critic Pauline Kael. Fellow roundtable filmmakers John Houseman (Lust for Life [1956], All Fall Down [1962]), Irvin Kershner (Stakeout on Dope Street [1958], The Hoodlum Priest [1961]), and Terry Sanders (Crime and Punishment, USA [1959], War Hunt [1962]) talked about strategies for retaining one’s artistic integrity in a money-driven and risk-averse industry.5 Mackenzie declared his personal discomfort with the task of trying to carve out a space for himself in a large studio and the difficultly of working outside the commercial system. He was disheartened by how long The Exiles had taken to complete, the uncertainty of its future, and the fact that it did not model a path forward for future endeavors. He had hoped that the project would appeal to an art cinema audience interested in topical issues. However, after a year of planning and research, three years of shooting and editing, and a year on the festival circuit, the documentary was badly in need of distribution.

As The Exiles continued to garner attention and play in festivals and small venues in the 1960s, Mackenzie worked in the city’s growing documentary sector. Like many of his colleagues, he made films for Wolper Productions and the United States Information Agency (USIA), both of which played leading roles in America’s cultural Cold War against the Soviet Union. These jobs offered the chance to make films about charismatic human subjects and afforded a degree of creative autonomy, but they also required that the films conform to the ideological strictures of their parent organizations. Mackenzie’s career is illustrative in this regard, shaped as it was by a powerful combination of political forces as well as critical shifts in the film and television industries.

THE POLITICS OF PEDAGOGY

Mackenzie first studied film at Dartmouth College with Benfield Pressey, an English professor whose interests in teaching cinema had led him to Hollywood to observe production up close.6 After graduating in 1951 and serving for two years as an aircraft control officer in the US Air Force, Mackenzie went to Los Angeles in search of training that would prepare him for a career in motion pictures. He enrolled in the cinema department at USC during a time when university film education was booming. This trend was the consequence of three factors: the GI Bill, which enabled veterans to attend college for little to no cost; the post–Paramount Decree restructuring of major studios, which dissolved the traditional pattern of mentor-based systems of training; and the diversifying market for film and television, which required local skilled labor that could be hired on a short-term basis. Programs at UCLA, Boston University, Northwestern University, New York University, and especially USC were geared toward technical training as well as providing coursework in film theory, history, and style.7

Editor Melvin Sloan, cinematographer Ralph Woolsey, and sound technician Dan Wiegand taught Mackenzie to use the equipment and to effectively collaborate with a crew. The aspiring filmmaker gained a socially conscious orientation to the medium through the documentary and cultural history courses of Andries Deinum. The Dutch left-liberal émigré served as a production clerk and director for Twentieth Century–Fox, a research director for Douglas Sirk’s A Scandal in Paris (1946), and a technical advisor for Fritz Lang’s Cloak and Dagger (1946). Deinum was an advocate for progressive causes and the increased presence of minorities in the film and television industries. He was close friends with John Kinloch, managing editor of the black newspaper the California Eagle, and the Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens, whom he hosted whenever Ivens visited the city.8 When the House Un-American Activities Committee came to Los Angeles in 1947, Deinum stood up to the Red Scare. He helped build a case to defend the “unfriendly witnesses” subpoenaed to testify before the committee about their relationship to the Communist Party and suspected dissident actions. He later stated that he was “deeply involved in organizing conferences, meetings, and broadcasts around the issue, and kept materials relating to [the Hollywood 19].”9 Deinum’s involvement with the hearings and his association with Ivens resulted in his being blacklisted by the studios. He managed to find a sympathetic employer in USC professor Lester Beck, who hired him to teach cinema studies courses beginning in the early 1950s.

Aware of what Red-baiting could do to careers, Deinum was no activist in the classroom, but taught a liberal humanist approach to film. He recognized motion picture technology as possessing the ability to capture people in a distinct way. As he would later write in Speaking for Myself: A Humanist Approach to Adult Education for a Technical Age: “Film, alone of the arts, can display fully rounded, infinitely complicated human beings within their actual environment, interacting with it, and with each other; thus, it can show us the very processes of contemporary living as they occur.”10 When used effectively, film could lead to an in-depth understanding of human experience and the social and material conditions that impact peoples’ lives. Recalling his time in Deinum’s seminars, Mackenzie noted that he and classmates Erik Daarstad, John Morrill, Warren Brown, Robert Kaufman, Sam Farnsworth, and Vilis Lapenieks discussed these issues in relation to several key films: Robert Flaherty’s ethnographic Nanook of the North (1922) and Moana (1926), Joris Ivens’s Popular Front–themed The Spanish Earth (1937) and Power and the Land (1940), Jean Renoir’s poetic Grand Illusion (1937), George Stoney’s instructional All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story (1953), Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist Bicycle Thieves (1948), and Sidney Meyers’s social documentary The Quiet One (1949).11

USC proved to be intellectually nourishing for Mackenzie and his peers. Unfortunately, it failed to provide a safe haven for Deinum. HUAC called Deinum to testify in 1955, at which point he admitted to having once been a member of the Communist Party, but refused to name his compatriots: “I could not bring upon people who were to my knowledge innocent of any subversive intent the mental suffering that has befallen me. . . . The mentioning of names would have saved me a great deal of trouble, but it would have smashed me inside and ruined me as a man.”12 When USC president Fred D. Fagg Jr. suspended Deinum, Mackenzie and his friends formed a protest committee and sent a student petition to the president to try and get their mentor reinstated.13 Despite this effort, the un-tenured Deinum was summarily dismissed. Commenting on the incident, Martin Hall’s article for the American Socialist, “Decline of a University,” concluded with the statement: “Perhaps [Fagg] was too busy with preparations for the highly publicized 75th anniversary of the University to realize that by cheating students of their right to academic freedom he was writing another chapter in the process of decline of a once free university.”14 Barred from jobs in Los Angeles, Deinum joined the faculty at Portland State University, where he made his intellectual presence felt as a teacher in the classroom, organizer in the community, and member of Film Quarterly’s advisory board.15

Deinum’s teachings continued to influence his students at USC after his departure. Mackenzie’s fifteen-minute 16mm documentary Bunker Hill–1956 (1956) took a stand against redevelopment in downtown Los Angeles by spotlighting those threatened with displacement. The documentary looked specifically at a group of elderly pensioners living in Bunker Hill, a neighborhood loosely bordered by First Street (north), Hill Street (east), Fifth Street (south), and the Harbor Freeway (west).16 For years the area had been the subject of heated municipal planning debates. Bunker Hill was once the nineteenth-century stronghold of rich and powerful Angelenos, such as USC founder Judge R.M. Widney and mining and real estate magnate Lewis L. Bradbury. Beginning in the 1910s and accelerating post–World War I, the area’s wealthy white inhabitants followed the city’s expansion westward and working-class blacks, Mexicans, Italians, artists, single women, and the elderly streamed into the neighborhood. With Bunker Hill’s demographic shift, aging housing stock, and low tax base, the locale quickly developed a reputation as dangerous and decrepit. The crime novels of Raymond Chandler and low-budget Hollywood detective films frequently featured Bunker Hill, amplifying this reputation. Cultural historian Eric Avila notes that “film noir cast Bunker Hill as Southern California’s heart of darkness, a site that harbored crime, fear, and psychosis.”17 Drawing on the zeal of New Deal housing reform and aware of the need to accommodate the city’s expanding population, urban planners, politicians, and civic organizations proposed that the government should clear areas containing substandard buildings, revamp the commercial infrastructure, and create low-cost housing options for the area’s residents.18

The city’s Community Redevelopment Agency considered several options along these lines. Following the passage of the 1949 Housing Act, the Los Angeles Housing Authority entered into a federal contract for the creation of ten thousand units. Special assistant to the Housing Authority Frank Wilkinson led the charge to sell the concept, pushing for clearance of blighted areas as well as the creation of new (and in some cases integrated) public housing complexes complete with indoor plumbing, ventilation, and green space. Wilkinson and the Housing Authority teamed up with USC students Algernon G. Walker and Gene Petersen on the documentary And Ten Thousand More (1951) to build support for public housing. Taking cues from the British social documentary Housing Problems (1935), the film focused on a peripatetic reporter investigating the so-called “slums” around Chavez Ravine, Bunker Hill, and First Street and Alameda, then declaring the need for modern and spacious public housing units.19 The documentary, like Wilkinson’s other efforts, showed concern for providing affordable housing for the city’s low-income residents, but also demonstrated a lack of understanding regarding their local geographic ties. The Red Scare ultimately crippled the cause for public housing initiatives. Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler and chief of police William Parker stoked hysteria surrounding collective living as socialist and anti-American. The election of business-backed, conservative mayor Norris Poulson in 1953 marked a decidedly anti–public housing and pro-corporate direction for the city.

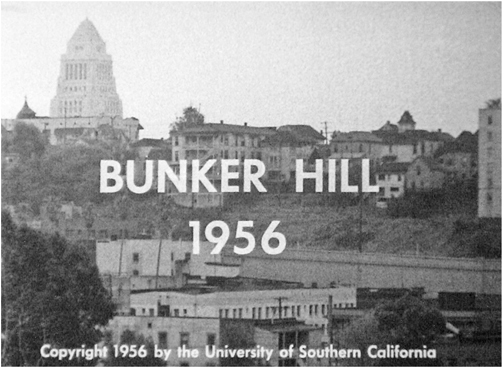

At the time when Mackenzie began making his student film in 1955, city officials were fast embracing urban renewal plans that benefited private interests and the civic elite rather than the public welfare. As seen from City Hall, the vision involved restructuring Bunker Hill in order to integrate it with the metropolis and facilitate a fluid expansion of the central business district. Organizations such as Greater Los Angeles Plans Incorporated and the Downtown Businessmen’s Association advocated that the city move in this direction. Hotels, cultural institutions, and office buildings, along with accompanying parking lots, roads, and plazas, were the hallmarks of the prospective plans.20 In contrast, Mackenzie’s Bunker Hill–1956 was boldly voiced dissent against the proposed top-down transformation of downtown. The documentary records how residents feel about their neighborhood and shows their efforts to sustain their community in the face of displacement. The film’s title shot signals this threat. A spectral City Hall looms over swaths of razed hillside and old buildings such as the Brousseau Mansion, the Earl Cliffe, and the Alta Vista. The opening voice-over, read against an extreme long shot of downtown, sketches the stakes surrounding redevelopment:

Close to the city center in downtown Los Angeles is a small residential area known as Bunker Hill. The Community Redevelopment Agency, a city agency created to clear slums, has selected Bunker Hill for a multimillion-dollar redevelopment project. The Community Redevelopment Agency hopes to condemn and buy all the property from the present owners, to move the eight thousand residents out, to demolish the buildings, and then to sell the cleared land to individuals and corporations who can afford to build in accordance with the agency’s master plan.

FIGURE 6: Still from Bunker Hill-1956, 1956, 16mm; written, directed, and edited by Kent Mackenzie; photographed and edited by Robert Kaufman. Courtesy of the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts’ Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive.

This statement sets the terms of contest. Present-day residents are being moved out by forces beyond their control to make way for a new and modern downtown.

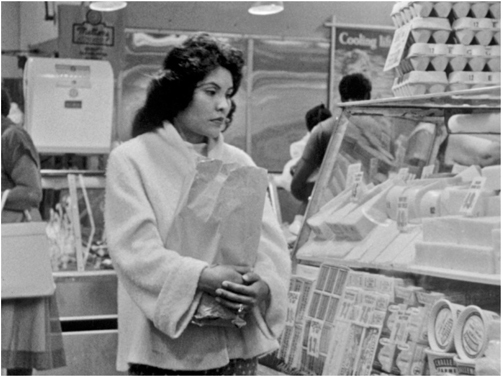

After several newspaper headlines show the redevelopment plans, the film shifts from a bird’s-eye perspective to an on-the-ground exploration of Bunker Hill. Testimony from druggist Louis Mellon, cobbler William Varney, and doctor James Green, coupled with a range of views of domestic interiors and scenes of commerce and interpersonal interaction, register how residents are rooted in place. Mellon opens his Angels Flight Pharmacy and a customer makes a purchase. Working in his shoe repair shop, Varney files down a heel and then goes home for lunch. Dr. Green checks the blood pressure of a patient. The Angels Flight railway brings residents to the bustling Grand Central Market. People gather for drinks and conversation at the Montana Cafe and Bar (where Mackenzie himself is in the crowd) or sit for a quiet respite on street-side benches lining Third Street and Grand Avenue. Emily Mills shapes little clay sculptures at her desk while listening to her radio. Besides periodic pans or tilts, the generally static position of the camera during these scenes of everyday life contributes to the sense of strongly willed desire for stability. The residents state that they are not opposed to change as such, but want a municipal strategy that favors rehabilitation over displacement. Mellon announces:

If they really had an equitable plan for the benefit of the majority, they would come up with an idea to rehabilitate this area and let the same people that live here now stay here. . . . Their method of going about it is to not only clear the slums, but clear all the people out, and re-beautify the whole thing, put an opera house up here, make a picture area out of it, without keeping the inhabitants in mind at all.

Other residents echo this sentiment. They are in favor of a revitalization effort that seeks to renovate aging housing stock (most of it created before 1920), connect inhabitants to public services, and build up the commercial and residential infrastructure. Residents want to have some input as to the present and future of their own neighborhood. And if they have to move, they want to be part of the decision-making process, both for the practical reason of ensuring that they can afford a new home, and to feel that they are playing an active role in deciding their own future. Relocation conjures angst about the severing of bonds, and fears as to where the next move will take them and how much it will cost.

USC made Bunker Hill–1956 available to the educational film sector as a way to promote discussion about urban revitalization. Journalists also praised the documentary as a well-made and moving film. Variety and USC’s newspaper, the Daily Trojan, enthusiastically noted that Mackenzie’s documentary played at the Edinburgh and Venice film festivals. The Los Angeles Times ran a picture of Mackenzie when he won the Silver Medallion award from the Screen Producers Guild and Look magazine. USC department head Robert Hall submitted the documentary to Margaret Herrick to be considered for an Academy Award, including in his submission letter that the film was successfully screened at the Flaherty Seminar.21 Despite this positive reception, Bunker Hill–1956 did not alter the immediate course of redevelopment planning. It did, however, give voice to a community that was rarely seen or heard, and led to Mackenzie’s future filmmaking endeavors in downtown Los Angeles.

EXILES ON MAIN STREET

At the same time that Hollywood documentarian David Wolper was shifting from distribution to production, Mackenzie began working in educational film firms scattered across Sunset Boulevard, Las Palmas Avenue, and Temple Street. These companies catered primarily to schools, corporations, and religious organizations looking to use 16mm nonfiction as a teaching tool. The combination of the Sputnik launch, scandals in the broadcasting industry, and the Kennedy administration’s attentiveness to the pedagogical power of audiovisual technology would soon increase nonfiction opportunities, especially as the television market expanded over the course of the decade. Making an award-winning film at USC facilitated Mackenzie’s employment. Laboring in the educational sector offered a steady stream of jobs, the ability to continue pursuing nonfiction media, and the chance to develop his own projects in his free time. Beyond serving as an editor and cinematographer for the Frederick K. Rockett Company, Modernage Photos, Telecast Productions, and the William Brown Company, Mackenzie led the documentary unit for Parthenon Pictures. Catering to clients such as Bell Telephone Laboratories, the American Petroleum Institute, and Merrill Lynch, Parthenon styled itself as a boutique firm, proudly stating in Business Screen Magazine that it made films that were “handled personally and with quality by its key group” rather than generating mass-produced “commercials.”22

Early on in his tenure at Parthenon, Mackenzie read a Harper’s Magazine article that piqued his curiosity about a promising topic. “The Raid on the Reservations” castigated House Concurrent Resolution 108, a policy that essentially terminated the treaties and legal rights of American Indian tribes. The piece reserved hard judgment for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) relocation program, which provided subsidies and the promise of job training as a way to encourage American Indians to leave their reservations and live in big cities.23 The article had particular relevance for Los Angeles, since more American Indians had moved or were moving from the Midwest and Southwest to that city than to Chicago, Denver, Oklahoma City, Seattle, or Tulsa. Between 1950 and 1960, the American Indian population in Los Angeles swelled from 1,671 to 8,109.24

Government officials and business leaders during this era championed Los Angeles as the epicenter of professional and leisure opportunities, supported by means of new highways, residential tracts, university campuses, cultural institutions, and industrial plants and factories. Still, metropolitan expansion did not benefit all residents. Some American Indian veterans did attend college on the GI Bill, and others managed to acquire training and found good jobs in the automotive or aerospace industries. But most earned money in commercial or domestic service jobs or served as short-term laborers in construction. Finding steady employment was hard, and discrimination on the job as well as in the housing market was rampant. As the government shifted from resource-poor, termination-focused policies toward an assimilationist approach to relocation, Mackenzie remained fascinated by the issue. The BIA expressed little regard for having American Indians themselves contribute to policy or the implementation of relocation initiatives.

The agency understood moving to the city as an act of separation from life on the reservation, which, in turn, only contributed to feelings of alienation. As historian Ned Blackhawk explains, these programs “tried to force individual American Indians to choose between competing and, in the government’s view, incompatible lifestyles.”25 Despite organizations such as the Indian Center located on Sixth Street in the Westlake District near downtown, which served as a communal hub, there was negligible public financial support for Native culture in these new locales. The government made it onerous for American Indians to visit their families back on the reservations and gave insufficient economic assistance to help program participants adjust to life in the metropolis.26

Mackenzie originally conceived of a documentary that would portray an Apache family’s migration from an Arizona reservation to Los Angeles. The prospective film would offer policy recommendations to the BIA. Mackenzie’s boss, Charles “Cap” Palmer, was supportive of the project and gave Mackenzie time off to conduct research with tribal leaders and government officials at the San Carlos Indian Reservation near Globe, Arizona. Mackenzie promised in his funding proposal:

With three months’ detailed research split between San Carlos and Los Angeles, and then ten weeks’ shooting, as previously estimated, Cap and I can pin this down and deliver a 40 minute film for general non-theatrical release which will analyze the situation with honesty, dimension, and passion. . . . We will work in the tradition of the human and social documentary, and the Indian point of view will be paramount. We do not pretend that this will be easy, and feel that the pressure may force the development of new techniques.27

The project’s conceptual blueprint shifted when Mackenzie began socializing with a group of American Indians he met at bars around Third and Main Streets. He turned away from wanting to create an expository account of a migratory journey and moved closer to an intimate look at a group of Bunker Hill residents. The film, as Mackenzie was now imagining it, would explore the gap between how journalists, Hollywood producers, and state institutions understood American Indians, and how American Indians lived in Los Angeles. The goal was not to create a didactic narrative, but rather to show the everyday interactions of a community systematically given short shrift in both commercial media outlets and the civic life of the city.28

Mackenzie’s approach was shaped by his affinity for 1930s-era social documentary and the recent international New Waves, as well as by the practical constraints he encountered during filming. His film school friends Daarstad, Morrill, Kaufman, Lapenieks, and Farnsworth joined his crew without salary. Mackenzie put his life savings of $539 into the film as starting funds, with friends, acquaintances, and arts patrons contributing additional money. The Screen Directors Guild of America extended a $1,200 grant and left-liberal Hollywood cinematographer Haskell Wexler and producer Benjamin Berg donated a crucial $8,000 to bring the film to completion. The crew relied on cheap equipment or whatever could be borrowed from employers at their other jobs. This involved shooting with a 35mm Arriflex on studio-donated “short ends.” They used a combination of Masterlites, clip lights, and car headlights to illuminate interiors and many exterior scenes. When experiments with synchronizing the camera for sound quickly proved too expensive and difficult, they used a Magnecorder and a Magnasync Recorder for capturing sound on location. They also relied on Parthenon soundstages for recording dialogue, singular voices, and sonic effects.29 Following on the ideas of film theorists from the 1920s and 1930s such as Paul Rotha, Mackenzie saw staging, artificial lighting, and dubbing sound as useful for rendering social reality intelligible and engaging.30 Commenting on this method in his thesis, Mackenzie wrote that the subjects in the film “were playing themselves in locations which were the locations of their everyday lives, wearing the costumes they always wore, and surrounded by the friends they were always with.”31 He went on to elaborate that the crew elicited constant input from the people they filmed. The production and editing involved a dialogue about the structure of the film and the cultural meaning of the daily rituals. The soundtrack was not scripted ahead of time, but emerged from informal conversations and interviews with American Indians.

FIGURE 7: Foreground to background: Kent Mackenzie, Robert Kaufman, and Erik Daarstad, on-location production photograph for The Exiles, 1961, 35mm; written, produced, and directed by Kent Mackenzie; photographed by Erik Daarstad, Robert Kaufman, and John Morrill. Courtesy of Milestone Films and the Mackenzie Family.

While The Exiles was a collective undertaking, there were definitely limits to the collaboration. At times referring to himself as the “film author,” Mackenzie saw his role as the film’s artistic compass, influencing its overall tone, tempo, and themes by asserting his editorial opinion during each phase of production. This view came less from the teachings of Deinum and more from the emerging cinemas of Europe and Japan, where the role of the director was recast as an auteur, an artist-craftsperson realizing a personal vision through the filmmaking process. When they were not making their own films, Mackenzie and his circle admiringly watched the films of François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Akira Kurosawa at the Linda Lea on Main Street, the Vagabond on Wilshire, the Coronet on La Cienega, and the Pantages and the Egyptian on Hollywood Boulevard.32 Mackenzie’s artful approach to The Exiles raised its profile as an accomplished work of cinema, but also separated it from the community that it represented as well as from the educational film sector.

The arc of the seventy-minute documentary captures approximately twelve hours of a Friday night with Yvonne Williams (Apache), her husband, Homer Nish (Hualapai), and Homer’s friend Tommy Reynolds (Mexican and Indian).33 Yvonne spends her evening watching films at a sparsely populated Roxie Theatre on Broadway and then strolls the sidewalks. She looks longingly at lavish displays of cosmetics, jewelry, and clothing in shop windows and storefronts. She reflects on how a wayward partner and economic hardship have caused her to reject as a fantasy the idea of a religious, happily married life; however, the prospect of a child gives her hope for a meaningful family life going forward.

Yvonne’s husband, Homer, drifts with different friends between the Ritz and the Columbine bars on Main Street and a poker game at their friend Rico’s nearby apartment on First Street. Tommy dances, mooches, and flirts his way through the night at many of the same watering holes as Homer. Whereas Tommy and Homer end the evening with a group of other American Indians on Hill X, located a short drive from Bunker Hill, Yvonne meets with her friend Marilyn, whose husband similarly stays out late. They tell stories in Marilyn’s home in the Sunshine Apartments and keep each other company until morning. Monologues that fade in and out of the ambient noise, dialogue, and the blistering rock ’n’ roll soundtrack by the Revels add a degree of psychological depth and realism to each of these narrative strands, connecting the individuals’ inner thoughts to their social actions.

Tommy, the most happy-go-lucky of the three male friends, says that he avoids thinking about larger goals by living in the moment and surrounding himself with people who share his attitude. Yvonne conveys her frustrations with her perpetually absent husband and the bar scene that draws him away. She speaks with a quiet confidence about her ability to raise her soon-to-be-born child with the hope that the baby will be able to realize the kind of educational and professional opportunities denied to her. Homer ruminates on his disillusionment with school in Valentine, Arizona, and recalls the antipathy he felt for camera-toting tourists. Around the same time, Homer receives a letter and photograph from his family on the Hualapai Reservation in Peach Springs, Arizona. The letter evokes a tender domestic scene that is either Homer’s personal memory or an event referenced by the note: A dissolve moves the scene from city to country. Slow pans reveal a sparse, windswept rural landscape. A woman, presumably Homer’s mother, teases his father as he sings a song about a rabbit under a tree. This scene underscores how geographically and culturally far Homer is from his family. The camera’s momentary pause on the small letter and photograph signal his connection to his family via correspondence. Homer expresses boredom with his friends’ nightly drinking and the perpetual carousing and grandstanding. He is uncomfortable and unfulfilled with the bar scene on Main Street, but speaks appreciatively of Hill X. After a gathering on the outskirts of downtown, Homer and his friends return to Bunker Hill. The film’s early-morning ending suggests finality, as the night wanderings are over and the characters return to their respective homes.

FIGURE 8: Still from The Exiles, 1961, 35mm; written, produced, and directed by Kent Mackenzie; photographed by Erik Daarstad, Robert Kaufman, and John Morrill. 1920 × 1080 ProRes 422 (HQ) transfer from the UCLA Film & Television Archive’s restored 35mm interpositive, courtesy of Milestone Films and the Mackenzie Family.

Even though The Exiles moved away from the kind of advocacy-oriented tone of Mackenzie’s student project, it nonetheless denounced the preponderant perspective on the area as an unlivable slum in need of sweeping redevelopment. The Exiles sharply contrasted with the account of Los Angeles advanced by urban theorist Kevin Lynch in his widely read book The Image of the City (1960), in which he argues that people navigate cities by means of an interpretive “reading” of memorable landmarks, spatial patterns, and sensory cues. He goes on to claim that downtown Los Angeles, as opposed to Boston, is disorienting, “alien” and even “menacing.”34 Countering this view, The Exiles made downtown legible, demonstrating that it was dotted with meaningful landmarks and that small groups of people were able to comfortably navigate its landscape.

Mackenzie’s film constitutes a symbolic resistance to the course of downtown urban change. While Bunker Hill–1956 explored Bunker Hill at a time when the fate of the neighborhood was not necessarily sealed, The Exiles depicted the area at a time when plans for demolition were already being put into effect. On March 31, 1959, a little more than a year into the shooting of The Exiles, the Los Angeles City Council approved the $315 million, 136-acre Bunker Hill Urban Renewal Plan. The plan put into motion the razing of Bunker Hill properties and the leveling of the hill itself. Between 1959 and 1964, close to ten thousand people were forced out of their homes. Many American Indians moved to Los Angeles Street to live in the Baltimore, Roslyn, and King Edward residency hotels. Others moved to industrial districts such as Long Beach, Huntington Park, and Bell Gardens.

Mackenzie could have amplified the sense of injustice by foregrounding the demolition that was already underway and interviewing American Indians about the displacement. Still, his decision to bracket off these issues helps keep attention focused on the presence of American Indians in this area and their close ties to their routines. Cinema and media historians point to The Exiles’s depiction of a soon-to-be-demolished neighborhood as a significant indication of its value. David James asserts that the film is “a unique record of lost civic vitality and demotic architectural richness.” Norman Klein writes that The Exiles comprises “the most complete body of imagery that exists of Bunker Hill’s daily rhythm.” Catherine Russell discusses the film in terms of the “expressive phantasmagoria of ‘everyday’” in a neighborhood that was fast being leveled.35

The social charge of the film extends beyond the politics of urban planning and its own status as a historical record. The Exiles troubles the cultural discourses surrounding American Indians during the period. Since the 1910s, Hollywood Westerns had depicted American Indians (who were often played by red-faced white performers) in violent, nineteenth-century confrontations with white lawmen, soldiers, migrants, and townspeople. Seen as a menacing threat or as possessing a primitive innocence, Indians were portrayed as a people whose culture was being erased by the advance of white civilization and the promise of modernity. In the early 1960s, Westerns appeared with renewed vigor on theater screens and home television monitors. The cultural historian Richard Slotkin argues that the early-1960s “cult of the cavalry” subgenre treated the Indian Wars of the nineteenth century as allegories of counterinsurgency scenarios in the Third World.36

The diegetic settings of The Exiles’s private and public spaces remind viewers of the ubiquity of the Western imaginary in American life. When Yvonne is dropped off at the local movie theater, she apathetically watches what is being exhibited that evening: The Iron Sheriff (1957). And when Homer goes with Rico to his apartment before their poker game, the sound of a six-shooter pistol reverberates from the television and a character says, “I reckon that’ll teach the moon-faced ‘Injun’ to have more respect for his betters.” Other forms of popular culture amplified this image of American Indians as a primitive people of the past. Disneyland’s Frontierland opened in 1955 in Anaheim, California, offering “authentic” powwows and tribal dances; five years later on the East Coast, the Bronx-based Freedomland opened, featuring canoe rides, “Indian attacks,” and handicrafts displays. In his 1961 introduction to William Brandon’s The American Heritage Book of Indians, President Kennedy observed, “For a subject worked and reworked so often in novels, motion pictures, and television, American Indians remain probably the least understood and most misunderstood Americans of us all.” Unfortunately, the four hundred ensuing pages failed to deliver a contemporary perspective on their entrenched presence in the country.37 The seemingly endless stream of maps, glossy portraits, and pastoral prose fossilized the voices and faces of American Indians, and completely buried Brandon’s claim that “the once ‘Vanishing American’ is far from vanished.”38 Even the image on the title page is infused with a rhetoric of pastness: a progression of American Indians move from left to right and from foreground to background across an expanse of water. The progression reveals a shift from bodies, to abstract shades, to absence. The image visualizes what the text implicitly narrates: that American Indians have essentially vanished.

From its opening moments The Exiles adamantly challenged this framework. A montage of Edward Curtis photographs culled from his North American Indian project cuts to still images and then short scenes of the film’s main characters in and around Bunker Hill. They appear near the exteriors of apartments on Clay Street, the Angels Flight railway, and the Grand Central Market. This sequence marks a discursive shift from a “vanishing” people to a minority community’s effort to sustain their culture within the post–World War II metropolis.

The scene on Hill X gives evidence to this struggle. The location appears as a haven, safe from constant police harassment and unjust arrests. Homer’s voice-over where he explains, “Indians like to get together where they won’t be bothered, you know, watched or nothing like that,” plays against shots of police twirling their billy clubs as they patrol the sidewalks. Officers punch a man, then tackle him to the ground and drag him into a squad car. Hill X serves as a crucial albeit temporary social site where American Indians can congregate under the cloak of darkness and away from the discriminatory eye of law enforcement. As Homer illustrates, people can maintain connections to reservation life by circulating news and telling stories. The late-night gatherings can mitigate feelings of alienation by way of socializing. People drink, talk, fight, and also join in the drumming, singing, and dancing known as a “49.” The informal performance atop Hill X is a focal point of the meeting. It features Mescalero Apache Indians Eddie Sunrise Gallerito, Frankie Red Elk, and Chris Surefoot leading a “Social Dance” and a song derived from a Sioux “Grass Dance” for a gathering of individuals of diverse tribal affiliations.39 The hybridity of the act combined with the collective investment in its performance speaks to Los Angeles as a city where new culture is continuously drawn from different pasts, giving fresh purpose to old rituals.

The fact that this gathering overlooks Chavez Ravine emphasizes the sense of instability shared by multiple minority communities in Los Angeles. In the 1940s, almost four thousand mainly Mexican American residents called the three close-knit rural neighborhoods of Chavez Ravine home. With housing conditions poor and access to basic utilities extremely limited, the site was originally slated for redevelopment as the Elysian Park Heights housing project. When plans for public housing were eliminated, the city’s pro-growth coalition thought that the site could be better used for creating car-accessible, middle-class entertainment. Bringing the Brooklyn Dodgers to Chavez Ravine would give the city its first major league baseball franchise, bolster its national reputation, and contribute to the restructuring of downtown as a cultural destination. Only months into the production of The Exiles, television station KTTV broadcast a Hollywood-hosted “Dodgerthon” to sway the public to embrace this plan and move ahead with creating a fifty-six-thousand-person stadium. Citizen opposition to Dodger Stadium was dismissed, and residents were removed from their homes. Soon after the shooting of the Bunker Hill scene in The Exiles, police started barring access to the area around Hill X as stadium plans moved forward, forcing American Indians to find alternative gathering places in the city.40

Just as The Exiles rejects the idea of American Indians as simply a people of the past, it also criticizes stereotypes of American Indians as a social problem. John Frankenheimer’s Sunday Showcase television special The American (1960) and Delbert Mann’s theatrically released The Outsider (1961) were two of the most prominent films to represent American Indians in this negative light. Both biopics broke new ground in their presentation of Pima Indian and World War II hero Ira Hayes living in tension with a white society that fails to acknowledge his grievances. But both productions contained a white star (Lee Marvin and Tony Curtis, respectively) performing in red face. Additionally, both films present Hays as a stand-in for the American Indian, an essentially victimized figure. Unlike The Exiles, these biopics had little patience for, or interest in, exploring the domestic interiors and social spaces in which American Indians lived. The broader media coverage of American Indian relocation also ignored this latter point of view. Instead, television reports and newspaper editorials tended to focus on statistics, policy decisions, and the opinions of government officials.

The Exiles’s festival success stemmed from its stylized approach to capturing quotidian reality, combined with the fact that it was made by a young filmmaker outside the Hollywood system. Covering the 1961 Venice Film Festival, Variety called Mackenzie “another budding indie U.S. filmmaking talent,” and praised The Exiles for having the “tingle of life and a polish in technical qualities and visual presentation.” Variety also described Mackenzie as part of a coterie of independent filmmakers that included Morris Engel and Ruth Orkin (Little Fugitive [1953]), Lionel Rogosin (On the Bowery [1956]), Bert Stern (Jazz on a Summer’s Day [1960]), Sidney Meyers (The Savage Eye [1960]), John Cassavetes (Shadows [1959]), and Shirley Clarke (The Connection [1961]).41

There was good reason to place Mackenzie and The Exiles within the pantheon of independent American film. Mackenzie, like his contemporaries, was considered part of a groundswell of homegrown auteurist cinema. The Exiles and other New Wave American films discussed in the festival reviews shared some thematic concerns and stylistic tendencies. These films captured commonplace interactions in working-class parts of cities within a short span of time. Although Cassavetes worked with professional actors for Shadows, the film chronicles a group of young black and white writers and jazz musicians in the streets, apartments, and clubs of Manhattan. Rogosin’s On the Bowery explores the bar culture of the working poor and the homeless men living on the Bowery in Manhattan. Closer to home, The Savage Eye captures the anxious strolls of divorcee Judith McGuire (Barbara Baxley) as she attempts to escape loneliness and search for companionship among Los Angeles’s leisure establishments. Stream-of-consciousness voice-over banter between McGuire and a heard but never seen “poet” narrator (Gary Merrill) accompanies shots of McGuire meandering around department stores, beauty salons, bars, sports arenas, strip clubs, and lounges. USC professor and educational film innovator Sy Wexler, who served on Mackenzie’s master’s thesis committee, was a cinematographer for the film. Additionally, Warren Brown, who was an editor for The Exiles (and became Mackenzie’s brother-in-law) was credited as a cameraman on The Savage Eye. Haskell Wexler, who, as noted, provided Mackenzie with the completion funds, was another cinematographer on The Savage Eye.42

While The Exiles was considered part of this American New Wave, it was also admired for its distinct subject and style. Individuals ranging from William J. Speed, director of the audiovisual department of the Los Angeles Public Library, to Film Quarterly’s Benjamin Jackson commended the film for highlighting the complexity of the American Indians’ experiences in Los Angeles. One of the film’s key strengths, Jackson wrote, was how it cited past nonfiction precedents but charted an original path. Jackson declared that the film skillfully depicts real American Indians and rejects the sentimentalizing tendencies of Robert Flaherty’s ethnographies, the technocratic didacticism of John Grierson’s state-backed social documentaries, and the “hyper-formalism” of city symphonies.43 When Mackenzie showed The Exiles to American Indians, including those who appeared in the film, he commented that they responded to it as to a “family album,” taking pleasure in the intimate experience of watching their lives with their relatives and close friends. They enjoyed a feeling of recognition and identification, even as some expressed concern that it did not cover a broad enough range of American Indians or that some might interpret the film as negative.44

The Exiles’s subject and style attracted the attention of individual journalists and film festivals, but greatly diminished the prospects of a wide release. The fact that The Exiles was a documentary about a minority community that most people did not know existed in Los Angeles undoubtedly hurt its chances for finding a larger audience. In describing the process of trying to get the film into theaters or on television, Mackenzie said that distributors simply found The Exiles extremely “difficult.” His former USC teacher, the Hollywood screenwriter Malvin Wald, confessed, “Perhaps [The Exiles] will never be known as anything more than a unique experimental film.” In a locally syndicated AP article, Bob Thomas reported that The Exiles played to a packed Royce Hall at UCLA, but that it was having trouble reaching a mainstream audience.45 The Exiles’s length, along with its refusal to conform to a rigorous pedagogical structure or a tight narrative, barred it from being considered a desirable film for the commercial entertainment, art house, or noncommercial sectors. While theaters around the country were beginning to more frequently exhibit documentaries, European art cinema, and the experimental work of Stan Brakhage, Jack Smith, and Kenneth Anger, they were uncomfortable with a slowly paced film focused on the lives of American Indians.

The fact that The Exiles was not on the radar of many within the American film vanguard further inhibited its chances of distribution. The New York journal Film Culture’s anticommercial stance translated to an anti–Los Angeles bias and a zealous championing of New York as the sole American center for independent filmmaking and criticism. In an article for its summer 1960 issue, journal founder Jonas Mekas proclaimed:

New York has always been in opposition to Hollywood, not only geographically but ideologically as well. It is here that the most perceptive American film critics and film historians live and work. . . . It has to be stated here that the role of the Hollywood independents has been greatly exaggerated. The best Hollywood tradition movies (Anatomy of a Murder, Giant, Ben Hur) still come from the larger Hollywood producers. The best anti-Hollywood movies, however, have little to do with Independents. They come from individual East Coast filmmakers, from those filmmakers who came under the direct influence of the East Coast cinematic climate (Shadows; Weddings and Babies; On the Bowery).46

But distribution was not the only impediment to the film’s success. The project had been expensive to create and every aspect of it had moved lethargically. Looking at job prospects, Mackenzie felt that going to work for a major studio to create fiction films or crime, comedy, or dramatic television did not seem particularly appealing. In an interview for Los Angeles Magazine devoted to the vicissitudes of film financing, Mackenzie spoke on behalf of independent filmmakers when he said, “We have decided there is no place for any of us in the industry to make the kind of films we want to do here in Hollywood. Methods of production are so stilted and conventional it’s death for us here.”47

Thus the concept of “exile” resonates in multiple ways with Mackenzie’s film. Restorationist and theorist Ross Lipman has detailed how “exile” points to the American Indians’ feeling of living as outcasts from both reservation and urban life, as well as to Mackenzie’s pursuit of a film language that was unlike either classical fiction storytelling or sync-sound documentaries. Additionally, “exile” could be seen as relating to Mackenzie’s ousted mentor Andries Deinum, and to his own feeling that he must operate outside of major Hollywood studios.48 Unable to replicate The Exiles, Mackenzie continued to support its public life at festivals while working in the educational film sector. He found employment at new organizations devoted to documentary. His films for Wolper Productions and the USIA would come with some enticing freedoms and some severe restrictions.

THE WAY OF WOLPER

As Wolper Productions rapidly expanded in the early 1960s, becoming the largest producer of documentaries in Los Angeles (and rivaling the output of ABC, NBC, and CBS), the studio sought to employ the young talent around town. Although making television documentaries for Wolper gave Mackenzie a paycheck, the chance to work with compelling subjects, and an audience for his films, the streamlined style and themes of the projects contrasted with Bunker Hill–1956 and The Exiles. The studio drew on classical Hollywood storytelling techniques along with tropes from network news to entertain and educate television audiences about cultural trends, politicians, major twentieth-century events, and the professional lives of American citizens. Wolper and his inner circle of executive craftsmen—Mel Stuart, Jack Haley Jr., and Alan Landsburg—ensured that the structuring story arcs and themes of these programs affirmed an upbeat image of the country as free and democratic while also critiquing communist and fascist systems of government. There was little room within Wolper Productions for interrogating the aspirations, limitations, and pitfalls of Cold War liberalism.

Like numerous film school graduates in the city, Mackenzie’s USC-classmates-turned-Exiles-collaborators made documentaries for Wolper. Some joined immediately following graduation. Others held jobs at the studio in conjunction with crewing on other films, and still others used the studio as a springboard to work on theatrically released features or documentaries at bigger companies. It was not uncommon for a Wolper employee to also make short films for corporate clients, telefilms for the networks, documentaries for the government, and fiction films for major studios or producers on the fringes of Hollywood. Vilis Lapenieks helped shoot Roger Corman’s The Little Shop of Horrors (1960) and Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide (1961) before joining Wolper as an assistant to James Wong Howe on Biography of a Rookie (1961). Lapenieks then went on to serve as one of Wolper Productions’ core camera operators in addition to crewing on projects such as Donn Harling’s Fallguy (1962). Eventually he worked on New Hollywood productions such as Cisco Pike (1972). Erik Daarstad shot science and nature shorts for Pat Dowling Pictures, and Burt Topper’s B-action film Hell Squad (1958), before being hired at Wolper Productions. Daarstad also made the Academy Award–nominated The Spirit of America (1963), and films on the Democratic and Republican conventions. Malvin Wald had a robust career writing acclaimed Hollywood films (The Naked City [1948]) and television (Playhouse 90 [1957]). Wald went on to become one of the major writers for Wolper Productions. His scripts for Hollywood—The Golden Years (1960), Biography of a Rookie (1961), and The Rafer Johnson Story (1961)—each launched a series.

Wolper Productions consecutively hired Mackenzie for a number of jobs. He edited three episodes of Story of . . ., a series that followed the activities of different professionals. An April 18, 1962, Variety advertisement for Story of . . . highlighted the series’ documentary appeal for a mainstream audience:

(a) outstanding quality and style (b) real stories of real people in real, challenging situations (c) adventure, suspense, surprises, emotional impact (d) a lot of appeal for every part of the audience, regardless of taste, income, age, background, viewing habits (e) it ushers in a new wave of programming that people will talk about.49

Mackenzie’s programs for the series included Story of a Test Pilot (1962), which profiled Lockheed Martin’s chief test pilot Herman “Fish” Salmon, who had proved the viability of the F-104 training vehicle; Story of a Jockey (1962), featuring the jockey Bill Harmatz spending time at his home, in his real estate office, and at the Santa Anita racetrack; and Story of an Intern (1962), accompanying the doctor Bill Farrell on his rounds at San Francisco General Hospital. Mackenzie also edited The Way Out Men (1965), a program that profiled men breaking barriers in science and art, including surgeon Michael DeBakey, physician and psychoanalyst John Lilly, architect Paolo Soleri, and composer Lukas Foss.50 That same year, Mackenzie edited Prelude to War (1965), which explored the years of German military aggression leading up to World War II, from the reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936 to the attack on Poland in 1939.

Mackenzie took a prominent role as the director, producer, editor, and cowriter for Story of a Rodeo Cowboy (1962). With the aid of his old collaborators Daarstad (director of photography), Farnsworth (production manager), and Nicholas Clapp (associate editor), Mackenzie documented third-ranking world champion saddle-bronc rider Bill Martinelli and his fellow riders Bob Edison and Jim Charles as they attempt to win prize money at the Salinas Valley Rodeo. As in his past independent productions, Mackenzie filmed a subculture up close over a short period of time. The film looks at the rodeo cowboys over the course of their professional routine: getting dressed in their spurred boots, blue jeans, plaid shirts, and hats in their motel room; inquiring about their respective animals before the event at the stadium; riding in the competition; dancing at the 5-High Club honky-tonk during their free time; and departing for another rodeo. The immersive cinematography positions the spectator in close proximity to the cowboys throughout their journey.

Dramatic moments punctuate these observational scenes. For example, in Martinelli’s last ride an extreme long shot captures his body in slow motion accompanied by Gerald Fried’s Americana orchestral score. Martinelli looks balletic as he struggles to stay on the horse, clutching the rope with his left hand while his right hand waves in the air, and then perfectly dismounts and lands on his feet. At various points in the film, Martinelli ruminates on how rodeo riding offers him freedoms denied to those who work in nine-to-five office jobs, as well as close-knit camaraderie with his fellow competitors. The riders do not appear to fall into lockstep with white-collar America, but their rugged individualism is nonetheless tailored to match the ambitions of the series and the studio that produced it. For all of the rodeo cowboys’ bravura, they labor in highly regulated settings and play by the prescribed rules of the competition. They are athletes, not outlaws, and apply themselves to what is seen as a meritocratic contest that rewards diligence and individual skill. The periodic commentary of John Willis familiarizes the viewer with Martinelli’s sport, suggesting that rodeo riding is a profession that requires talent, ambition, and perseverance.

Mackenzie’s other major Wolper Productions project was The Teenage Revolution (1965), in which he investigated teenagers in two related ways: first, as an empowered group of twenty-three million consumers, and, second, as young citizens learning to navigate evolving relationships with their peers, school, family, and government. In part one, narrator and on-screen host Van Heflin moves like an amateur anthropologist through the schools, homes, and commercial establishments of white, middle-class Southern California. He interviews teenagers about their use of clothing, music, and cars to fashion individual identities. Testimony from market researchers, fashion designers, and tastemakers such as music producer Phil Spector depicts teenagers as a volatile market demographic whose preferences are constantly changing. The relationship between producers and consumers of culture is seen as dynamic and symbiotic, resulting in a seemingly unlimited set of expressive possibilities. The second half of The Teenage Revolution profiles academic achievers. National Science Award–winning high school student John Link receives mentorship from his teachers, support and assistance from his peers, supplies and resources from industrial companies, and purpose and recognition from the Atomic Energy Commission. Mackenzie also profiles the Job Corps, whose members work with underprivileged children in community-based summer programs in Los Angeles and other metropolitan cities. A counter–case study in The Teenage Revolution looks at Henry Hine, who despite his desire to support himself and his family dropped out of high school early and is frustrated, has low self-esteem, and has difficulty finding a job.

American youth appear armed with the power of choice in The Teenage Revolution. If they can make the right choices, the documentary implies, they can thrive within a society being transformed by new aesthetic sensibilities, technological inventions, and educational opportunities. All discussion of factors that influence the opportunities available to them such as race, gender, and class remain noticeably absent from the program, as if every teenager is in a position to make similar decisions. Furthermore, The Teenage Revolution amplifies the civic ends to which creativity and intellectual labor can be applied while also ignoring how fashion, music, and art can be used as possible means of social resistance.51

DOCUMENTARY DIPLOMACY

The USIA’s program of state-backed auteurism enabled Mackenzie to create his own film about a topic that would otherwise not have been commercially viable. Filmmaker George Stevens Jr., who led the organization’s film operations, tapped Mackenzie to make a documentary about a government-sponsored job training program. This was a common entrée into employment for the USIA, which recruited heavily out of Los Angeles. Mackenzie’s fifteen-minute, 16mm A Skill for Molina (1964) follows a day in the life of Arnold Molina, a welder in training of Pima Indian and Mexican descent living in Fresno, California. Mackenzie had a greater amount of artistic freedom than at Wolper Productions, but his film still had to conform to the agency’s overt Cold War mission.

Founded under President Dwight Eisenhower in 1953, the USIA aimed to “submit evidence to peoples of other nations by means of communication techniques that the objectives and policies of the United States are in harmony with and will advance their legitimate aspirations for freedom, progress and peace.”52 Beginning with the Kennedy administration, the USIA amped up its efforts to support American foreign policy by means of film, photography, literature, and radio. These forms of media sought to emphasize the positive impact of the United States on the world and to affirm the tenets of American democracy. The USIA also assumed an advisory role, gathering information about the reception of the United States abroad. Seasoned news anchor Edward R. Murrow directed the USIA from 1961 to 1964. Committed to the president’s vision for intensifying the cultural Cold War, Murrow proclaimed, “We are being outspent, out-published, and out-broadcast. We are a first rate power. We must speak with a first rate voice abroad.”53

During this period, the USIA reached over one hundred countries through its seventy magazines and twenty newspapers, 180 libraries, and 789 annual hours of Voice of America radio broadcasts in thirty-six languages.54 Motion pictures in general and documentaries in particular had a major role to play in the USIA’s public relations initiatives. Murrow asked the filmmaker George Stevens Jr. to lead the International Motion Picture Service. The director had collaborated with his father on A Place in the Sun (1951), Giant (1956), and The Diary of Anne Frank (1959), and operated independently on Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1960–61). He also served in the Air Force Motion Pictures Division. Stevens would recall that he was inspired by the idea of public service after reading Theodore H. White’s The Making of the President: 1960, the book that Wolper had adapted into an Emmy-winning documentary. The Stevens family name ensured that the agency would be infused with the aura of Hollywood as well as a good civic pedigree.

The Murrow-Stevens duo formed an American analogue to John Grierson, the documentary theorist, public relations pioneer, and savvy technocrat who helped to create strong state-backed systems of educational film in England and Canada. The USIA organized the international exhibition of big-budget American features and arranged for actors and directors to serve as cultural diplomats. According to the Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, the USIA in 1962 created 44 films in the United States, acquired 36 titles, created 147 overseas productions, and made 197 newsreels. Each was translated into multiple languages. These films reached millions of viewers in 746 theaters and had 226 “film centers” in 106 countries.55 As Congress did not want a government agency to be in competition with private enterprise, USIA films were not usually shown domestically but sent to theaters, museums, community centers, and schools in cities and towns across the globe, especially in nonaligned countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. Press coverage of the organization created a public awareness of recent films, the personnel involved, and the organization’s broader aims. Exhibition of USIA productions at the Edinburgh, Venice, Moscow, and Bilbao film festivals promoted American film achievements and boosted the international profiles of the filmmakers.

This was not the first time the government had strategically used nonfiction. Film historian Richard Dyer MacCann writes that the Office of War Information’s practice of reaching out to directors during World War II provided a foundation for how the government could work productively with individual filmmakers on a short-term basis for an international cause. However, unlike in the past, USIA documentaries were not crafted with the purpose of preparing both a civilian population and troops for an active war with fixed fronts and an enemy to destroy. Rather, they intended to project a positive impression of American democracy and expose the weaknesses of alternative systems of governance. Commenting on the delicacy of this task, Stevens proclaimed, “Ideas are fragile things, and they can’t be turned out on an assembly line like sausages or jeeps.”56

The USIA made films advertising Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress initiatives to increase economic cooperation with Latin America (United in Progress [1963]), the lasting impact of civil rights reform in the South (Nine from Little Rock [1964]), the congenial, bridge-building diplomatic travels of Jacqueline Kennedy (Invitation to India [1962]), and respect for American labor (Harvest [1967]). Stevens understood that a well-made, compelling narrative that engaged with people emotionally could be more persuasive to spectators than a dry catalog of facts: “We are not interested in making travelogues. . . . We are trying to show how democracy works and how people can help themselves in developing nations. . . . Our country has developed a marvelous mechanism in its movies, and it must use this wonderful tool to explain its way of life to other countries. But such movies, to be successful, must have quality and vitality.”57

Although based in his USIA office in the nation’s capital, Stevens looked beyond Washington, DC, for gifted filmmakers. USIA filmmaker Gary Goldsmith (The True Story of an Election [1963], Born a Man [1964]) would later recall that Stevens really “had the sense to recruit the best young filmmakers that he could,” rather than just seek the “low bidder.” Stevens would often contact an individual upon seeing his or her film at a festival or on television. A positive reputation in the industry could also attract the attention of the agency. Stevens would then reach out to the individual about the possibilities of working on a particular project and invite the submission of a treatment that would need to be approved before filmmaking began.58 The USIA sponsored nationwide competitions for student filmmakers and took on interns whose abilities could be cultivated, used, and then connected to the mainstream industry. Given that Los Angeles was home to prestigious film schools and was also the nation’s center for the film and television industries, the city appealed as a talent pool. The conservative Hollywood director Bruce Herschensohn, Cold War liberal documentarian David Wolper, left-leaning intellectuals Haskell Wexler and James Blue, and fresh-out-of-film-school, socially minded graduates of UCLA and USC such as Mackenzie, Daarstad, and Carroll Ballard all made films for the USIA during the early to mid-1960s.59

The agency embraced a wide range of subject matter and formal variation. Stevens told Film Comment, “The important thing is to have an individual’s mark on the film rather than just going to a manufacturer of film and saying: ‘Make this film for us.’”60 The idea was to show how American artists, unlike artists working within a completely state-controlled framework, possessed a greater degree of individual freedom. The USIA’s desire to promote filmmakers as independent, free-thinking artists, combined with the lack of a singular directive for the organization, made for a less restrictive production environment than most commercial studios. Media historian Jennifer Horne writes that the freedoms filmmakers enjoyed at times even enabled their critique of American foreign policy and the USIA itself. James Blue’s trio of documentaries about American-Colombian relations, in which he visualizes the human consequences of industrialization and satirizes the staid form of a governmental newsreel, “could be thought of as ambassadors who do not hesitate to speak out of turn, subverting their diplomatic mission.”61 Nonetheless, even as the USIA provided filmmakers the chance to creatively address topical issues that Hollywood studios and commercial news networks refused, subversion or overt criticism was uncommon. The USIA’s insistence on promoting pro-American, pro-democracy, or anticommunist sentiment, as well as the fact that the agency retained the right to the final cut, resulted in broad ideological cohesion across its vast output.

Mackenzie directed and produced A Skill for Molina (1964) with collaborators Daarstad and Morrill, who handled the cinematography. The film depicts Molina as an indefatigable student, father, and husband, committed to raising his family’s socioeconomic standing through learning a skill in the special program at Fresno City College. In a series of connected scenes that chronicle the unfolding of a day, Molina studies diligently at the dining room table before his children awake, appears thoroughly invested in his classes, plays dominoes with his peers, and spends time with his wife and nine children in the evening. Voice-over narration from Molina combined with a montage sequence of small photographs offer backstory concerning the economic and emotional hardships he endured growing up poor in Chandler, Arizona, and laboring as a seasonal farmworker prior to his arrival in Fresno. He also talks about his frustrations with looking for a job after having served in the navy during World War II and the Korean War. The narration at times has an expository function that informs viewers about Molina’s schedule. At other times it comprises an interior monologue of Molina’s thoughts. As he reads with his children, cuts their hair, or asks them questions about school, his narration communicates his desire for his children to study hard and attend the local city college so as not to endure what he went through. Formal education, he implies, is important to gaining the skills that will lead to full-time, stable employment. Toward the end of the film, extended takes show the family bonding over tortillas at the dining room table. The Bolivian American composer Jaime Mendoza-Nava, who had worked on everything from the Mister Magoo television series (1960–61) to the theatrically released Fallguy (1962) and The Quick and the Dead (1963), wrote the score for the documentary. The music imbues both the voice-over and the observational sequences with varying degrees of levity and gravity, conveying that Molina is enjoying life with his family and taking his education and prospects for steady employment seriously.

A Skill for Molina reflected Mackenzie’s devotion to crafting poetic day-in-the-life portraits of people marginalized within or distorted by popular culture. The commission of Mendoza-Nava involved reaching outside the predominantly white film and television music divisions, echoing Mackenzie’s old mentor Andries Deinum’s fight to bring minority talent into the media industries. Additionally, Mackenzie’s compassionate depiction of Molina as industrious and resilient opposed stereotypes in magazine articles, cartoons, and Hollywood films of the Mexican and Indian as a transient, lazy, poor farm laborer. Scenes that show Molina working and socializing with other minorities as well as white students also foreground the shared aspirations for economic mobility and job security that exist across racial and ethnic lines. Molina’s children and grandchildren didn’t see the film as propaganda, but as a “home movie” created by a compassionate stranger. Family members felt that Mackenzie captured both the heartfelt intimacy and the high energy pace of their group dynamic. The documentary would later serve as an occasion for the extended family to gather together and tell stories about the lives of the individuals depicted on-screen.

A Skill for Molina also spoke to the USIA’s interests in promoting the state as a benevolent and caring presence in the lives of citizens, spotlighting how public programs could smoothly incorporate industrious minorities into the American workforce. Molina is essentially the protagonist in an “American dream” success narrative circa 1964, one based on realizing opportunities given to him by public institutions. The film’s title signals that Molina is receiving a means to mobility. The film does not address contemporary discrimination in hiring practices or the impact of race prejudice on residential life in the region. It presents an idyllic state of harmony, showing black, brown, and white welders learning together, living near one another, playing dominoes, carpooling, and joking around in the locker room. Daarstad and Morrill’s verité-style camerawork captures the details of Molina’s tasks, helping to personalize his story and show that he is a productive member of a larger welfare initiative. Shots of Molina up early studying in his kitchen, concentrating on his welding exercises at school, and happily eating and doing homework with his kids in the evening demonstrate the success of the program in action. The importance of secondary-school education is seen as both useful knowledge that Molina is passing on to his family and a way of validating the institutions in which he now receives training.

Mackenzie’s film embodied the USIA’s eagerness to encourage filmmakers to take ownership over their projects, as well as the agency’s tendency to showcase high-functioning relationships between the government and its diverse populace. A Skill for Molina circulated globally and played at select venues in the United States, such as the School of Visual Arts in New York, where it had a special screening and accompanying panel discussion.62 Over the course of the 1960s, the agency continued to embrace motion pictures as a means to promote Lyndon B. Johnson’s vision of the Great Society abroad. Bruce Herschensohn’s John F. Kennedy: Years of Lightning, Day of Drums (1964) was even released theatrically to an American audience in 1966. The documentary touted the fallen president’s policy achievements and claimed their ongoing vitality within the Johnson administration. However, the rise of minority liberation movements within US cities, along with growing opposition to the country’s aggressive foreign policies, would soon give way to a crisis in Cold War liberalism. These tensions reached a flash point in Los Angeles, discouraging plans (at least for the moment) for the sweeping redevelopment of downtown, and energizing grassroots organizing in working-class minority neighborhoods. Mackenzie’s films in Bunker Hill anticipated the efforts of other white liberal filmmakers. At the same time, his documentary practice would itself become the object of contentious debate, as marginalized groups sought to directly represent their own communities.63