3

The Rise of Minority Storytelling

Network News, Public Television, and Independent Collectives

Television coverage of the 1965 Watts Uprising broadcast an image of Los Angeles unfamiliar to most Americans. Scenes of urban chaos appeared in living rooms across the city and around the country, shattering the popular image of Los Angeles as a placid West Coast metropolitan paradise. In KTLA’s compilation film Hell in the City of Angels (1965), newscaster Hugh Brundage discussed how the August 11 altercation between police and the family of Marquette Frye on the corner of 116th Street and Avalon Boulevard escalated into a week of chaos. He spoke of “hoodlums” committing “indiscriminate” acts of “violence” that brought about rampant destruction.1 Aerial views from the station’s telecopter surveyed burning commercial establishments along Avalon, police officers trying to disperse crowds and making arrests, and individuals carrying stolen objects moving quickly down alleys and sidewalks. Close-up shots of damaged news vehicles and debris-strewn streets were meant to convey the danger journalists faced covering the event and the generally unsettling atmosphere. In an interview, cameraman Ed Clark described Watts as a “war zone” that was “worse than Korea” and mayor Sam Yorty confidently declared that the only effective way to meet the “mob” was with “overwhelming power.” The documentary primarily framed and edited Watts residents running, yelling, and looting, advancing the mainstream media’s perspective that the unrest was simply a hateful and confused expression of rage. KTLA’s coverage was consistent with the alarmist headlines in the Los Angeles Times, leading stories in Time and Newsweek, and Universal Newsreel’s Troops Patrol L.A. (1965).

The geographic reach of the conflagration in Watts effectively halted mid-1960s plans for significant downtown development, as investors moved to the white Westside instead.2 Nationally, as the Watts Uprising occurred only five days after the signing of president Lyndon B. Johnson’s Voting Rights Act, which outlawed discriminatory practices that disenfranchised minorities, it signaled a rupture in the Great Society, a plan that the president had been trying to strengthen and expand. Johnson declared in a speech at the University of Michigan and then wrote in his book My Hope for America, “The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. . . . It is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents.”3

This idea of the Great Society did not end after the Watts Uprising. Johnson’s administration moved to address the urban strife as part of its effort to actualize its broader vision of what the expanded welfare state could achieve. The Great Society consisted of a multipronged policy initiative comprised of: race relations (the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965); community-based antipoverty programs (the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964); education (the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965); health care (the Social Security Act of 1965); and arts and culture (the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965 and the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967). Poverty, racial tension, and all forms of socioeconomic inequality could be fixed, the administration confidently thought, through creative forms of legislation, an increase in opportunities for able and willing citizens, and a spirit of public service.

Politicians, entrepreneurs, and civic leaders were eager to explain “the problem” of Watts and urged the city to move forward. The CBS Reports documentary Watts: Riot or Revolt (1965) provided a stage for “experts” to pontificate on the meaning of the event. It reinforced the recently published Violence in the City—An End or a Beginning? authored by governor Edmund Brown’s Commission on the Los Angeles Riots.4 Members of the commission, led by the conservative former CIA director John McCone, contended that there was a fractious relationship between the black community and police and considered the uprising a detestable act of anger rather than a protest. In the documentary, Police Chief William Parker blames members of the black community for the current crisis. He states that a criminal element in Watts, stirred up by civil rights leaders, was creating unreasonable demands and promoting widespread disrespect for police. The film also reinforced secretary of labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (1965), which claimed that the disintegration of the black family was at the heart of problems in Watts and that improving male employment was the clear way to strengthen families and uplift the blighted neighborhood.5 Amid the talking heads, the faces and voices of Watts residents appear as fleeting images or sound bites.

Participants in the uprising, however, were not simply hoodlums, nor was the neighborhood in which they lived simply a problem to be solved. The unrest stemmed from the persistence of police prejudice and use of excessive force, the neighborhood’s severely limited access to public utilities, exploitation by business owners, and the lack of employment opportunities for both men and women. Los Angeles’s support for the ballot initiative Proposition 14 (1964), which sought to negate antidiscriminatory housing legislation, revealed the entrenched racism in the city. Compounding these problems was the fact that mayor Sam Yorty remained intransigent about the prospect of federal money alleviating poverty in Los Angeles.

In the aftermath of the uprising, white liberals made films within commercial broadcasting that peered beneath the sensational facade obscuring many people’s understanding of South Central. Stuart Schulberg and Joe Saltzman were dissatisfied with the conventions of public affairs programming. They aimed to create greater awareness among white viewers concerning some of the challenges that black Angelenos faced, increasing constructive channels for interracial dialogue. Schulberg and Saltzman’s films did succeed in registering a profound sense of frustration and conveyed some of the motivations behind the Watts Uprising. Nevertheless, they were primarily aimed at white audiences and did not engage in depth with Black Power as a political movement.

As the 1960s progressed, other minorities and women drew inspiration from black liberation struggles. They shared some of the same criticisms of the limitations and inadequacies of the discourse of liberal integration as well as the desire for self-determination. Documentary media was essential to the black, brown, yellow, and women’s movements. Their presence was acutely felt in Los Angeles—the film and television capital of the country and the most racially diverse postwar American metropolis. Marginalized people of the city demanded the right to assert their voices from behind the camera, arguing that self-representation was crucial to self-determination. With cinema being such a resource-intensive craft, many citizen groups, filmmakers, activists, and intellectuals fought for increased access to money, equipment, and training. Others went outside, and indeed positioned their work against, commercial or public systems of production.

In an attempt to provide a space for a greater plurality of voices to be heard within an increasingly fraught democracy, the shell-shocked mandarins of the Great Society were compelled to respond, without always the clearest idea of what providing increased access to education, equipment, distribution channels, and exhibition venues would entail. While schools such as UCLA played a crucial role in cultivating filmmakers’ interests and providing training, the university was one among numerous institutional frameworks that had an impact on local production. Filmmakers drew heavily on an expanding array of schools, workshops, foundations, studios, and broadcasting facilities. They gravitated to documentary out of practical necessity, but also because of its distinct social utility. Documentary offered filmmakers an economical form of reportage while also enabling them to interpret the sociopolitical geography of the city. They aligned their films with the fight against police brutality, the whitewashing of school curricula, egregious pop culture stereotypes, political disenfranchisement, systemic racism and sexism in the workplace, and the US imperial involvement in Southeast Asia. The documentaries they produced were viewed in libraries, theaters, private homes, neighborhood centers, schools, churches, and union halls. Such films claimed both physical space in the city and discursive space within contemporary liberation movements. In so doing, these documentaries helped forge the political consciousness of marginalized communities across the country and constituted a form of community advocacy that engendered lasting social change within Los Angeles.

NETWORK RENEGADES

The two television documentaries by Stuart Schulberg were early interventions into how the mainstream media represented South Central Los Angeles. Stuart and his brother Budd grew up in Beverly Hills and had numerous ties to Hollywood. Their father was the New Deal–supporting Paramount mogul B.P. Schulberg. Stuart could have pursued a more traditional career making studio fiction, but instead went into public affairs documentary. His Cold War liberal outlook was informed by his experiences making educational films for the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, the US military government in Berlin, and the Marshall Plan Economic Cooperation Administration in Paris. He believed that film could perform a valuable social service and assist in stabilizing democratic societies. His documentaries promoted advances in modern technology, industrial expansion, collective security, and international trade and business, all while reinforcing the image of the pro-democracy, pro-capitalism United States as a decisive force for good. Stuart returned to the United States in the mid-1950s and worked in NBC’s Washington, DC, offices as a producer for David Brinkley’s Journal (1961–64).6

His films about Watts emerged out of his brother’s literary outreach after the uprising. As the cultural studies scholar Daniel Widener writes, Budd Schulberg’s Watts Writers Workshop was motivated by concern for his home city, guilt for being naive about the hardships facing his fellow Angelenos, and hope that creating a cultural outlet could calm racial tensions and provide professional guidance for aspiring writers.7 The workshop attracted around twenty individuals who met at the Westminster Neighborhood Association at 10125 Beach Street in Watts. They soon expanded and relocated to the nearby Watts Happening Coffee House and then the nine-room Frederick Douglass House. Budd led sessions where he encouraged workshop members to share their feelings of alienation from white America by means of poetry, prose, and plays. His brother proposed making a documentary on the workshop that would allow a national audience to understand the thoughts and frustrations of black residents as well as create a bridge for local talent to the nearby film, television, and publishing industries. Stuart, like Budd, felt confident that his good intentions and expertise in strategic communication could aid the process of racial integration. NBC News vice president Don Meaney calculated that the Schulberg brothers’ production would generate a lot of attention, given the family’s prominence, and demonstrate that the network was invested in socially conscious programming.8

The Angry Voices of Watts: An NBC News Inquiry was filmed in ten days during the summer of 1966. The documentary adhered to the standard network convention of a trusted, white male interpreter framing the subject matter. It begins with Budd, as narrator and guide, driving down 103rd Street, past the vacant lots, the ABC Loan store, the Giant Food Market, and Block’s Yardage. He comments that he is working “in a ghetto, within a ghetto, within a ghetto,” but that he has been able to make a unique and positive impact on residents’ lives through his workshop. Inside the Watts Happening Coffee House, he gives a brief profile of some of the writers before introducing sample works. The individuals’ dramatic readings play against on-location images that resonate with their words.9 Harry Dolan’s short autobiographical piece “The Sand-Clock Day” focuses on the difficulty and fatigue of searching for a job in the city. Dolan gets up in the morning and leaves his home in Watts, takes one bus to downtown and another to Van Nuys before arriving late to his interview. Sadly, he does not get the job. Shots of pile drivers and close-ups of conveyer belts accompany Jimmie Sherman’s poem “The Workin’ Machine” to convey anxieties about automation and the possibilities of unemployment. Black adolescents play baseball for Birdell Chew’s “A Black Mother’s Plea,” a manifesto-like prose poem about the desire for her son to grow up free from self-doubt and the threat of discrimination. In between readings, Budd assumes the role of host, mentor, editor, and therapist. He conducts the flow of the workshop, gives advice to the participants, commends their productivity, and offers comfort to Dolan when he is momentarily overcome with grief.

Upon the film’s airing on the anniversary of the uprising, Percy Shain from the Boston Globe wrote that it provided “an outlet for seared feelings.”10 The New York Amsterdam News’s Poppy Cannon White remarked that while the program’s title was sensationalistic, the show was “freighted with drama—the curious, but almost incredible drama of a vision made visible.”11 The program generated interest in the anthology of the workshop’s writing, From the Ashes: Voices of Watts, and had additional professional payoffs. Johnie Scott placed a poem in Harper’s Magazine. Television personality and composer Steve Allen set Jimmie Sherman’s poetry to music, and he was later hired as a screenwriter at Universal.12 NBC purchased Dolan’s script for the teledrama Losers Weepers (1967). The program portrayed a father who returns from prison to his 92nd Street home to reestablish a relationship with his children, as well as to retrieve some money he stashed away after a robbery.13 The Angry Voices of Watts also helped the workshop attract the financial backing of Steve Allen, Art Buchwald, James Baldwin, Robert F. Kennedy, and John Steinbeck.14

An article Stuart Schulberg penned for Variety reflected his optimism as well as his arrogance and naïveté concerning what he thought his film had achieved. He called himself “the leading authority on Watts TV production” and asserted that “white technicians who considered Watts north of the demarcation line soon felt as much at home there as they did in Burbank or Beverly Hills. Negro cast and (mainly) white crew, uptown pros and downtown hopefuls, merged into one happy if hard-working family.”15 Schulberg’s follow-up program, The New Voices of Watts (1968), mainly featured dramatic readings in the neighborhood.16 “Nobody loves the song out of captivity” exclaims Fredericka White, reading from her poem “Something of Mine” in front of the Watts Towers. “I am a black phoenix,” recites James Thomas Jackson, reading from his poem “Blues for Black” in front of a large junk heap. At a rehearsal for the domestic drama A House Divided, author Jeanne Taylor talks about the thrill of seeing others perform her work, how she draws on her own familial experiences in her art, and the satisfaction of sharing the “true” experience of growing up in Watts with a larger audience. The program’s other major segment consists of Birdell Chew’s teledrama The Time of the Blue Jay, which follows two black children who become curious about school following their chance encounter with an inspiring black teacher.

Despite the continuities between Angry Voices and New Voices, Stuart Schulberg’s New York Times article “Watts ’68: So Young, So Angry” revealed widening ideological rifts within the workshop. In the article, Stuart details his and Budd’s frustrated attempts to limit nationalist rhetoric and shape the literary style of some of the members: “We were confronted by four Black Nationalist poets so young, so angry and so proud that they overpowered our ability to communicate.”17 Stuart noted that the Four Furies poetry ensemble refused to censor their “four-letter words,” which prevented them from participating: “We tried to explain that they couldn’t say and on the air, at least not while this generation of fuddy-duddy Establishment whites still controls the airwaves.”18 But the trouble with New Voices extended to other aspects of the program as well. The black residents of Johns Island, South Carolina, where Chew’s film was shot, disrupted the production; they were dissatisfied that white personnel were in charge of the program. This was not the first time that the workshop faced public disapproval.19 Nonetheless, the difficulties besetting New Voices were symptomatic of growing opposition to the organization’s professionalizing mission which connected black talent to an exploitative entertainment industry. They also pointed to dissatisfaction with outside white “experts” claiming to be authorities on minority experiences. As the workshop attempted to reinvent itself, Budd Schulberg returned to novel writing. His brother continued on as a producer for NBC.

Stuart Schulberg’s documentaries in Watts anticipated the work of the white liberal documentarian Joe Saltzman for the CBS-owned-and-operated Los Angeles station KNXT; however, Saltzman’s Black on Black (1968) skirted the traditional role of the white newscaster. Born in Alhambra in suburban Los Angeles, Saltzman studied cinema at USC and served as the editor in chief of the school newspaper, the Daily Trojan. He then earned a graduate journalism degree from Columbia University. Returning to Los Angeles, he began his career in broadcasting as a reporter for KNXT’s Ralph Story’s Los Angeles (1964–69), a popular magazine-style series that covered the city’s cultural milieu. In the aftermath of the Watts Uprising, Saltzman proposed to station heads a documentary on Watts residents in which the film’s subjects would be the only voices heard. Saltzman believed that this format would create a sorely needed platform for black residents to speak honestly about their lives. In turn, the program would be educational for white viewers and result in more open and constructive channels for interracial dialogue in Los Angeles. KNXT rejected the idea, arguing that the absence of an in-house anchor would give viewers the impression that the station lacked control over its program content. Flagrant racism within the newsroom also initially stalled the program.20

Two factors in a nationwide climate of media reform eventually swayed KNXT to greenlight the project. First, a report issued by the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, chaired by Illinois governor Otto Kerner Jr., sent shock waves through television stations across the country. The report was the upshot of the Johnson administration’s July 27, 1967, mandate to explore the reasons behind four years of urban strife.21 The Kerner Commission researched the mass media’s interpretation of these events as well as the response of minorities to the media’s coverage. The document indicated that these outlets have “not communicated to the majority of their audience—which is white—a sense of the degradation, misery, and hopelessness of living in the ghetto. . . . They have not shown understanding or appreciation of—and thus have not communicated—a sense of Negro culture, thought, or history.” It detailed the need to bring a greater amount of minority personnel into the film, television, and newspaper industries and also claimed, “The news media must find ways of exploring the problems of the Negro and the ghetto more deeply and more meaningfully.”22 The commission’s findings had many proponents. In his front-page Variety editorial, FCC commissioner Nicholas Johnson wrote, “The media must get the Negro’s side of a story—not just that of the Welfare Dept. or the Police Chief . . . not just through the ‘filter’ of a responsible ‘spokesman’ or reporter.”23 The conflagrations in American cities following the April 4, 1968, assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. intensified the need for an inclusive approach to film and television.

The second major factor involved the efforts of lawyers, advocacy groups, civil rights leaders, and entertainment personnel to make television stations responsive to their minority constituencies. Their battle led to a 1966 court case against the station WLBT in Jackson, Mississippi, that established the right of citizens to participate in a station’s license renewal proceedings. A groundbreaking 1969 court decision stripped the same station of its license because of its failure to address the views of the area’s black community. Media historian Allison Perlman argues that the WLBT case showed that a station’s racist programming policies and lack of attention to minority audiences could serve as cause for revocation. The case also provided a precedent for future legal efforts to hold stations responsible to their viewers.24 Under pressure to respond to issues facing Angelenos, and distant from the New York–based oversight of the CBS network, KNXT executives shifted their position on Saltzman’s program from rejection to reluctant acceptance.

Saltzman and a small crew spent three months working on Black on Black, including three weeks on location during the spring and early summer of 1968. Saltzman’s liaison with Watts was Truman Jacques, a community organizer building his career in television. By way of Jacques, Saltzman met Donnell Petetan, a resident who worked for the Concentrated Employment Program helping to provide services to job seekers. Petetan became Saltzman’s main interlocutor with the neighborhood.25 Saltzman worked with KNX radio engineers for the editing of ambient noises, individual testimony, and music. “I was far more concerned with audio than video” Saltzman would later recall, for sound could document “the things that were happening inside the heart and the mind of the people.”26

Petetan appears at the beginning of the film, driving past small homes, the Watts Towers, children playing, housing projects, weed-filled vacant lots, and adult men and women walking down the street. He explains that Watts at once shares the salient characteristics of other black, urban, working-class neighborhoods and is also distinct in its makeup and relationship to its metropolitan area. He contends that although there is very little home ownership, and landlords are most often absentee, Watts is not simply a blighted terrain. Residents feel affection for and draw psychological support from the environment. The film then examines topics that coalesce around black identity, cultural practices, oppression, and hopes and anxieties for the future. Saltzman explores these subjects in one-on-one interviews. The spectator never hears Saltzman’s voice, and his own presence remains beyond the frame. While the interviewees speak, the camera frequently cuts away to observational sequences that match the content of what has now become voice-over narration. Speaking from his bedroom at his East 112th Street home, Petetan says that popular culture has for too long attached negative connotations to the adjective “black” and positive connotations to the adjective “white.” He argues that it is important to resituate the former as essentially affirmative and beautiful. Male and female interviewees then extend the discussion of identity, reflecting on the significance of wearing clothing that relates to their ancestral heritage or styling their hair to express racial pride. Speaking in his own shop, barber Walter Butler explains how at one time black people were urged by the cosmetics industry to process, curl, and straighten their hair, emulating that of whites. He claims that wearing “a natural” allows black people to develop a more authentic sense of self.

In additional scenes, individuals insist that conflict is part of everyday life, including television’s psychological attack on people of color. “Why does TV make fool[s] out of other races?” Petetan asks. Conflict can also be associated with face-to-face indignities. One young woman shares an aggravating story of a time when her boss discouraged her from applying for a higher-paying position. He thought she wouldn’t “enjoy working in this office where there are all white people.” Providing a sweeping critique of a racially divided workforce, Petetan’s mother Ethel looks directly at the camera and says, “I tell you why the white man is a snake in the grass. The white man will train you for any kind of job that he wants you to do. . . . He won’t train you for the better jobs.”

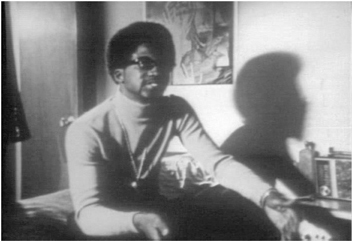

FIGURE 9: Still from Black on Black, 1968, 16mm; directed by Joe Saltzman; executive produced by Dan Gingold; broadcast on KNXT, Los Angeles. DVD courtesy of Joe Saltzman.

Black on Black does not try to build consensus or present a monolithic view of Watts. Religion, for example, is a divisive issue. Inside a service at the Garden of Eden Church of God in Christ, a woman shares with the congregation her belief that the church offers a safe and nurturing space for children. In contrast, Petetan says that religion is “the biggest hustle of all.” Household income is another debated topic. One mother says that she and her husband both work full time, as this is a necessary step toward home ownership and financial stability. Another woman says that it is important to have one parent stay home with the children in order to provide them with guidance. Black on Black stays focused on individual voices through its conclusion, where it presents residents’ desires and predictions for the future. While one woman declares that integration should be a goal for black people and that violence never yields tangible benefits, Petetan and his friend argue that violence is an American tradition that stretches back to the country’s founding. Presenting these voices as stand-alone, personal opinions arguably made Black Power seem less threatening for spectators of the documentary, presenting it as an outlook held by particular individuals rather than a mass political movement.

Following Black on Black’s July 18 premiere, Television critic Sherman Brodey wrote that the emphasis on Petetan-as-guide made Black on Black both part of, and different from, television’s recent turn to covering inner cities across the country. Variety stressed that Black on Black “transcended any previous effort to picture the black people as they are, without the embellishments of extraneous dramatization.” The Los Angeles Sentinel commented that most news programs provide a “recitation of statistics on crime, violence, poverty and despair,” but that Black on Black showed residents “articulat[ing] what it’s like to be black as it is to them.”27 The documentary won two local Emmys and various national broadcasting awards. Other CBS-owned-and-operated stations in St. Louis, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia showed Black on Black. Letters of praise sent to KNXT headquarters at 6121 Sunset Boulevard spoke to the show’s popularity, especially among white liberals. San Pedro resident Barbara Wasser wrote that “Black on Black, which appeared last night, offered me more insights into Negro problems than any show I’ve seen to date.” The film was even used to teach race relations at Horace Mann Elementary School in Glendale. But Black on Black was also subject to a conservative backlash. Saltzman recounted that after the program first aired, calls came in through the CBS switchboard denigrating the documentary as little more than liberal propaganda. A copy of Black on Black was mutilated by a patron within days of its being donated to the Los Angeles Public Library.28

Saltzman spoke extensively with residents in Watts about the documentary. In an early-August memo to his producer Dan Gingold, he communicated that although some people were extremely positive about the show, others lamented that it was an isolated program created by outsiders, that it did not represent enough voices, and that it would not lead to progressive change within the neighborhood.29 These were some of the same criticisms made about Stuart Schulberg’s films. They also revealed dissatisfaction and skepticism regarding the idea that making a mainstream audience aware of issues facing African Americans would have an incisive and lasting socioeconomic impact on that community. It was around this time that filmmakers began to look beyond commercial broadcasting in order to cultivate a militant political cinema. Los Angeles Newsreel viewed liberal film practice as incapable of altering the status quo, and thus decidedly ineffectual when it came to radical social change. They believed that to truly empower minorities and the working class, a militant leftist cinema needed to exist outside of, and indeed take a strong position against, the commercial culture industries.

RADICAL NEWS

Newsreel began in New York but soon had a branch in Los Angeles. The organization emerged out of a meeting called by avant-garde impresario Jonas Mekas and the filmmaker Melvin Margolis in late 1967 at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque. They talked about the need for films to counter the mainstream media’s representation of the antiwar March on the Pentagon. Network news and newspapers failed to take seriously the grievances of the protestors and the abuses they suffered. The core of New York Newsreel consisted of activists from Students for a Democratic Society and experimental filmmakers. Most of them were white, middle-class men. Local branches formed in Boston, Albuquerque, Detroit, Seattle, Atlanta, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.30 Newsreel contributed to what the documentary theorist Michael Renov calls the “political imaginary for the New Left.”31 Members sought to disrupt the consciences of spectators in an effort to politicize them, move them toward acts of resistance, and project the possibilities of what their actions might achieve. Newsreel’s purview included the related struggles of the New Left: campus protests against the corporatization of the university; antiwar demonstrations; the committed endeavors of Third World nations to break free of colonial rule and influence; and grassroots protests by women and communities of color to fight systemic discrimination at home. Newsreel was opposed to commercial film, television, and publishing, which they saw as extensions of the ruling class’s attempts to bolster economic and racial hierarchies.

San Francisco Newsreel’s Marilyn Buck and Karen Ross articulated the group’s hard battle lines in the winter 1968–69 issue of Film Quarterly. They described Newsreel as

a way for film-makers and radical organizer-agitators to break into the consciousness of people. A chance to say something different . . . to say that people don’t have to be spectator-puppets. In our hands film is not an anesthetic, a sterile, smooth-talking apparatus of control. It is a weapon to counter, to talk back to and to crack the façade of the lying media of capitalism.32

Early Newsreel films were short, 16mm, black-and-white productions and mainly came from the New York and San Francisco branches. Films were often conceived by collective debate, but those individuals with the financial means to create them held significantly more sway. Communal funds made available to filmmakers by the organization were, in reality, quite meager. On-location recorded sounds and images conveyed the immediacy and intensity of the action. Voice-over narration taught viewers about the meaning of the depicted confrontation. Editing, too, emphasized the tension between activists and oppressive institutions of the capitalist state. New York Newsreel’s Robert Kramer claimed: “Our films remind some people of battle footage: grainy, camera weaving around trying to get the material and still not get beaten/trapped. Well, we, and many others, are at war.”33 Introductions and post-screening discussions made viewing interactive, expanding audience comprehension of the film’s arguments. In its first two years, Newsreel covered a range of topics. Columbia Revolt (1968) concentrated on the student protests against the university’s expansion into Harlem; Off the Pig (1968) presented key principles of the Black Panthers and the need for the organization to take a stand against racist police and the judicial system; Garbage (1968) looked at the dumping of garbage in the plaza at Lincoln Center by the anarchist collective Up Against the Wall Motherfucker; and America (1969) explored the antiwar movement.

Los Angeles became a hub for the exhibition of Newsreel films, along with documentaries from Third Cinema filmmakers such as Santiago Álvarez. Films were available to rent from Los Angeles Students for a Democratic Society leader Jim Fite. The underground newspaper the Los Angeles Free Press advertised screenings and interviews with branch leaders.34 In his article “Guerrilla Newsreels,” the critic Gene Youngblood heralded Newsreel as “the most important mass communication development in this country in decades.”35 Los Angeles Newsreel began following an October 1968 screening of Off the Pig and established a small office at 1331 West Washington Boulevard in the unpretentious bohemian enclave of Venice. Approximately fifty people attended the first meeting, but the organization soon pared down to a smaller contingent composed of Ron Abrams, Jonathan Aurthur, Judy Belsito, Peter Belsito, Bill Floyd, Christine Hansen, Dennis Hicks, Mike Murphy, Barbara Rose, Elinor Schiffrin, and Stephanie Waxman. Like other branches, Los Angeles Newsreel was mainly white, middle class, and college educated. However, there was a more even gender balance. Also, the Marxist orientation of the members, along with their strong interest in organizing, steered the chapter toward exhibition rather than production. The collective worked with political groups to host screenings. Films supported these groups’ goals, raised the political consciousness of viewers, and served as catalysts for conversation. Los Angeles Newsreel showed films at rallies, union halls, welfare and unemployment offices, and branches of the Los Angeles Public Library. UCLA, California State College, Valley College, and City College were also popular venues for Newsreel films. Beyond Los Angeles, Hicks and Waxman screened Salt of the Earth (1954), a blacklisted film about a Mexican American zinc miners’ strike in New Mexico, for Chicano activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales’s “Crusade for Justice” event in Denver.

Los Angeles Newsreel collaborated closely with the Black Panthers, who drew extensively from the city’s black working class and unemployed youth. Bobby Seale and Huey Newton started the Black Panther Party in Oakland in October 1966. They saw self-determination as both a process and an objective for achieving the collective liberation of black Americans. Chapters formed in Baltimore, Chicago, Seattle, and Cleveland. Former Slauson Avenue gang member Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter established the Southern California chapter in 1968. The base of operations was Forty-First Street and Central Avenue. Geographer Laura Pulido describes the chapter as “notable for its size, commitment to self-defense, intense police repression, and leadership.”36 Carter embraced the Panthers’ revolutionary nationalism, and pursued an agenda of armed patrol, a free breakfast for children program, and a health care clinic. For recruitment and community education, Los Angeles Newsreel frequently screened Off the Pig at Panther headquarters. They also screened films with the Panthers for special events, including an antiwar picnic and teach-in at Fairmont Park in Riverside. The filmmaking collective’s initial four projects were never completed. These included documentaries about the Panthers’ free breakfast program, urban development in Venice, political unrest in Mexico, and the Lamaze method of childbirth.37 Los Angeles Newsreel moved adamantly toward production around the turn of the decade, just as the breakdown of unity inside Students for a Democratic Society, along with the FBI’s nationwide assault on the Black Panthers, inhibited the sustainability of the collective. Los Angeles Newsreel struck a defiant position. They became increasingly radical in the face of state violence in the streets and the persistence of the government’s war in Southeast Asia. Repression (1970), which was primarily shot and edited by Hicks and Murphy, decisively called for the cross-racial organizing of working-class people toward armed resistance.

A montage of photographs and archival footage at the film’s onset likens black labor to a form of imprisonment within the United States. The searing saxophone of Ornette Coleman’s “Sadness” plays against scenes of African Americans collecting garbage, picking cotton, working in a factory, and walking as part of a chain gang and in handcuffs flanked by police. The testimony of minister of education Masai Hewitt makes explicit the connection between race and economic exploitation, contending that minorities come to the United States from all over the world for the purpose of the white ruling class’s economic gain. Hewitt explains that racism is used to maintain an oppressive global capitalist system. The close-up on Margaret Bourke-White’s 1937 photograph Kentucky Flood contrasts the mainstream media’s whitewashed fantasy of the American dream with a stark Great Depression–era lived experience. The photograph shows black men and women standing in line for food and clothing under a billboard showing a white family happily driving in a car. The banner text reads, “World’s Highest Standard of Living: There’s No Way Like the American Way.” The photograph calls attention to the persistent incongruity between economic fantasy (as generated by the mass cultural industries) and grim quotidian reality. The image also highlights the idea that the freedom and mobility offered by the automobile seems to be geared toward whites only, that not all Americans can share in the thrill and practical benefits of having access to a car.

Repression then moves to the streets of South Central in the current moment. The film contends that recent attacks on the Panthers have been distorted or ignored by the mainstream press. Instead, Americans hear misinformation about the Panthers’ excessive use of guns, that they are inciting violence in the streets, or that Panthers are anti-white. Footage of children eating at the free breakfast program shows one of the organization’s constructive community activities, demonstrating that the Panthers give to hungry children what American businesses and the government have not been able to provide. Repression also spotlights the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department’s highly coordinated December 8, 1969, raid on Panther headquarters, occurring four days after the murder of deputy chairman Fred Hampton in Chicago. State authorities had been escalating their targeted assaults, arrests, and harassment of the Panthers over the past two years, resulting in the demise of Panther leadership on a local and national scale. In Repression, footage of the dilapidated, bullet-riddled exterior of the Panther headquarters, crowds of frustrated people milling around the entrance, and police patrolling the territory register the suffering experienced by the black community. Repression then declares that the Panthers are under attack from the government and black nationalist organizations collaborating with establishment politicians. Images of the funeral of Panther luminaries John Huggins and Bunchy Carter are paired with voice-over narration stating that both individuals were killed in a gunfight with the US Organization. Repression asserts that Ron Karenga and the US Organization, a black cultural nationalist group, have ties to the wealthy and political Rockefeller family and are responsible for the deaths of Huggins and Carter.

The film pivots here to call for solidarity and action. With many Panther higher-ups struck down, it argues, there is a need for new ones to come forward (as Elaine Brown’s song “The End of Silence” intones). Repression’s message is on one level an attempt to help rebuild the battered Los Angeles chapter. It is also an attempt to mobilize oppressed people across the United States. Panther leader David Hilliard and Los Angeles Newsreel’s Elinor Schiffrin and Jonathan Aurthur assert that viewers of Repression—black, brown, yellow, red, and white, male and female—should look not just to the Panthers for inspiration, but also to liberation movements in Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Angola as well as in Asia and Latin America. Repression claims that rebellion against capitalist institutions and the creation of an alternative, socialist system of labor is necessary to bring about a sweeping redistribution of power to the working class and the poor. Los Angeles Newsreel screened the film to Panthers, fellow radicals, and filmmakers at UCLA, but it was deemed too militant and ideologically loaded for organizing. It advocated for a path of leftist action that the collective and its allies were not prepared to pursue, nor was the confrontation it promoted practicably feasible. Repression was more revolutionary reverie than battle plan or blueprint.

The very same political shifts that Los Angeles Newsreel documented ultimately caused the collective to disintegrate. With the Panthers reeling from sustained attacks and internal tensions, the film collective lost the political organization with which it had aligned its operations. So, too, did sectarian infighting and the participation of the California Communist League compound its inability to function. Numerous members moved into factory work at the General Motors plant in South Gate or participated in local activism throughout the city. Film scholar David James argues that the city’s long-standing opposition to left-liberal organizations, as well as its fragmented social geography, inhibited the populist working-class cinema Los Angeles Newsreel envisioned and prevented the realization of Repression’s revolutionary aspirations.38 Also weighing against the possibility of imagining a future for Los Angeles Newsreel were growing pressures for minority access to the means of media production. Debates surrounding authorship and editorial control essentially fractured the production-focused New York Newsreel. In Los Angeles, people of color and women were beginning to make their voices heard from behind and in front of the camera, resulting in alternative models for politically engaged cinema. Filmmakers frequently struck a critical stance against government institutions and corporate power, but did not necessarily advocate for sweeping revolutionary change. Instead, they saw cinema as a means to build, strengthen, and politicize their communities.

HUMAN AFFAIRS AT PBS

Los Angeles had been slow to invest in noncommercial television, but Community Television of Southern California eventually established KCET in 1964. Hollywood insiders (David Wolper and Bob Hope), business leaders (Jesse Tapp of Bank of America and James Doolittle of Space Technology Laboratories), as well as communications conglomerate Metromedia were vocal supporters and contributed financial resources to its launch. KCET affiliated with the Ford Foundation–backed National Educational Television network and set up shop at 1313 Vine Street. Referencing how former FCC chair Newton Minow had famously disparaged Hollywood’s penchant for creating mass-produced entertainment television, critic Cecil Smith claimed KCET would give the Los Angeles “wasteland a shot in [the] arm.”39 However, financial setbacks and allegations that the station was too conservative in its programing led to a change in administration in 1967.40 Government support for public television legislation set KCET on a fresh path. As broadcasting scholar James L. Baughman writes, support for an expansive system of public television stemmed from the perceived failure of commercial broadcasting to address the concerns of diverse constituencies and to create programs with educational value.41 Lyndon B. Johnson, in his speech for the signing of the Public Broadcasting Act that same year, declared that public television “announces to the world that our nation wants more than just material wealth. . . . While we work every day to produce new goods and to create new wealth, we want most of all to enrich man’s spirit.” Public television, he hoped, could be used for “education and knowledge” for the nation’s citizenry.42 In many cases, public television reflected the Cold War liberalism and elitist tastes of its architects. Thus, programming meant documenting the high arts of classical music and ballet, teaching world history from a Western perspective, or offering instruction in practical skills.43 And yet, there was a strong, albeit vague, desire to create an inclusive media platform for people who were usually marginalized within American society. The Carnegie Commission on Educational Television’s seminal 1967 report Public Television: A Program for Action recommended that the government should play an active role in noncommercial television:

Public Television programming can deepen a sense of community in local life. It should show us our community as it really is. It should be a forum for debate and controversy. It should bring into the home meetings, now generally untelevised, where major public decisions are hammered out, and occasions where people of the community express their hopes, their protests, their enthusiasms, and their will. It should provide a voice for groups in the community that may otherwise be unheard.44

The Kerner Commission Report, in concert with progressive filmmakers, cultural administrators, and grassroots advocacy groups influenced the practical applications of public television’s programming mandate. This was especially true at the local level. At KCET, program director Charles Allen was committed to creating Los Angeles–centered, socially conscious shows. He recognized that the diverse communities of the city needed and demanded this kind of programming. In 1967 the station received part of a $3.5 million grant to help create the telenovela-style series Canción de la Raza (1968–70). The success of the show facilitated a follow-up Mexican American–themed series, ¡Ahora! (1969–70).45 KCET soon hired the young Mexican American filmmaker Jesús Salvador Treviño to work on the show.

Born in El Paso, Texas, Treviño grew up in the East Los Angeles neighborhoods of Boyle Heights and Lincoln Heights. He studied philosophy and cinema at Occidental College and became increasingly interested in politics. After graduating in 1968, he joined the Chicano movement, which coalesced around a number of issues: resistance to the Vietnam War, in which Mexican Americans were disproportionately killed; the 1968 walkouts by Mexican American students from East Los Angeles high schools protesting the city’s deplorable public school conditions and tendency to bar Mexican culture from the general curriculum; and the Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta–led labor protests in the Central Valley.46

Writer and community leader Frank Sifuentes brought Treviño into the recently established minority training program New Communicators. The Office of Economic Opportunity provided necessary funds and USC cinema professor Mel Sloan, filmmaker Jack Dunbar, and producer Mae Churchill oversaw the training sessions.47 Treviño attended classes at a converted bank located at 6211 Hollywood Boulevard. Fellow students Martín Quiroz and Esperanza Vásquez would become lifelong collaborators. Treviño first made the drama Ya Basta! (1968) about a Chicano student expelled from school and killed on the way home. Second, he made the newsreel La Raza Nueva (1969), which contextualized the recent school walkouts, the arrest of the “L.A. Thirteen,” and the sit-in at Lincoln High School in protest of the suspension of teacher Sal Castro. Third, he created a documentary about the National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in Denver, where the poetic manifesto “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán” was read aloud.

Treviño landed a job at KCET working with producer Ed Moreno on ¡Ahora!. He quickly advanced from assistant to associate producer to cohost. Rather than shoot the program at the station in Hollywood, Treviño and Moreno set up a satellite studio on 5237 Beverly Boulevard in East Los Angeles. In contrast to standard news and public affairs reporting, they actively sought a direct dialogue with the city’s Mexican American residents. KCET’s September 1969 program guide, which featured ¡Ahora! on its cover, announced that the series covered “the Mexican American community in all its aspects: art, music, economics, politics, problems, accomplishments and aspirations.” Moreno later emphasized in a Los Angeles Times article that the series stressed the city’s Mexican American roots as well as Chicanos’ contemporary contributions to public life: “Our heritage isn’t just Olvera Street, Sepulveda Boulevard, and enchiladas. It goes much deeper than that.”48 ¡Ahora!’s first episode comprised a cross-section of topical issues. Community organizers discussed the recent high school walkouts. Children from a Head Start program performed movement songs. Chicano painter Gilbert “Magú” Luján presented his artwork. And members of the League of Mexican American Women gave a talk. In later episodes, Treviño and Luis Torres introduced La Raza History, a weekly series of five- to ten-minute vignettes on Chicano history spanning hundreds of years.49 Treviño also produced the three-part documentary Image: The Mexican American in Motion Pictures and Television (1970). The first part attends to the different ways Mexican Americans have been stereotyped. The second part exposes discriminatory hiring practices against Mexican Americans in the entertainment industry. The third part argues for the need to increase the number of Mexican American producers, directors, and writers.

Treviño recalled that local residents frequently told him how much they appreciated ¡Ahora!. Following the screening of an episode at an Educational Issues Coordinating Committee meeting, the audience gave him a standing ovation.50 Notwithstanding the show’s appeal, ¡Ahora! was brought to a standstill in the spring of 1970 due to the costs of the large staff combined with an inability to secure additional funds from outside donors.51 Still, as film scholar Chon Noriega points out, the series served as a catalyst, encouraging the station toward Chicano-themed programming.52 The establishment of the Human Affairs department constituted an umbrella framework under which marginalized voices in the city gained a platform to speak. The department pooled financial and technical resources. Éclair cameras and Nagra recorders allowed for mobile, on-location shooting. Filmmakers crewed on one another’s projects and shared common topics and questions of interest, while still creating their own documentaries from distinct points of view. Their documentaries were penetrating forms of public history, bolstering a feeling of ethnic pride and dignity within their respective communities, and helping residents to talk to themselves about themselves. At the same time, their documentaries mobilized support against systemic forces of injustice. When Human Affairs evolved into the L.A. Collective (which brought together different nonfiction divisions within KCET) in the early 1970s, filmmakers continued to make stand-alone documentaries and series with the same ethos.

Treviño’s Chicano Moratorium: The Aftermath (also titled The Salazar Inquest, 1970) depicted the August 29, 1970, Chicano Moratorium march down Whittier Boulevard to Laguna Park. The mass demonstration against the Vietnam War brought twenty thousand Chicanos from Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. Many journalists mischaracterized the protestors as violent and disorganized. When the Los Angeles Times columnist and KMEX news chief Rubén Salazar was fatally shot by a sheriff’s deputy with a tear-gas projectile at the Silver Dollar Bar, the mainstream media sided with the courts and law enforcement and deemed his death an accident. Treviño’s nationally broadcast documentary provided a perspective from the Chicano community that countered “official” accounts. The film walks the viewer through the sixteen days of the inquest, by means of footage of the peaceful marchers, clashes with police, and court proceedings. KCET’s legal consultant Howard Miller explains how eyewitness testimony concerning the deliberate forcing of Salazar into the bar, along with his targeted killing at the hands of police officers, had been strategically silenced. The film played nationally on PBS and won the San Francisco Broadcasting Industry Award for Best News Program. Diana Loercher of the Christian Science Monitor wrote, “The Program’s most creative effect lay in instilling enough knowledge in the viewer’s consciousness, and conscience, to enable him to evaluate the factors for himself. The evident Chicano bias seemed more an attempt to give fair presentation to an underdog position than a departure from objectivity.”53

América Tropical (1971) explored the distant Mexican American past as essential to the construction of contemporary Chicano identity. Treviño’s film is at once a narrative account of the creation of a 1932 mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros, and a symbolic examination of the recent resurfacing of Chicano culture. América Tropical begins by looking at Siqueiros’s work in the city through sepia-toned photographs and interviews with the artist, his former collaborators, and art historian Shifra Goldman. Siqueiros was a committed socialist who frequently painted scenes of labor in his art. Workers’ Meeting (1932), the mural he created with students at the Chouinard Art Institute, portrayed an image of black, white, and brown manual laborers gathered together for passionate dialogue with a union organizer. The provocative image supported class solidarity to strengthen the strikes then taking place in California’s Central Valley, and condemned the forced repatriation of Mexican Americans. The owner of the Plaza Arts Center on Olvera Street subsequently wanted Siqueiros to paint a large mural of a tropical paradise. Siqueiros, the film explains, instead painted América Tropical, an image of violent oppression measuring eighteen by eighty feet. In the mural, an Indian is tied to a double cross, atop which a threatening eagle—the same that appears on the back of the US quarter—is prominently perched. The ruined Mayan temple in the background cements the theme of Western imperial violence toward indigenous peoples. The mural was quickly whitewashed over, and with the renewal of Siqueiros’s US visa denied, he had to leave the country.

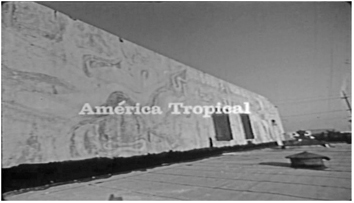

FIGURE 10: Still from América Tropical, 1971, 16mm; directed by Jesús Salvador Treviño; photographed by Barry Nye; broadcast on KCET, Los Angeles. DVD, Cinema Guild, New York, 2006.

América Tropical then shifts to the present. It portrays Olvera Street in the early 1970s as a quaint thoroughfare where tourists purchase sombreros and listen to mariachi music. Observational shots of the mural show Mexican art restorers discussing the possibilities of stripping away the whitewash, a material metaphor for cultural recovery. Commenting on the film at the time, Treviño asserted that the mural is “symbolic of the treatment the Chicano has had in the United States. . . . It reminds us that there have been other whitewashings, and that we are faced with some of the same feelings that were there in the early 1930s.”54 Contemporary artists in the film echo Treviño’s claims and announce that Siqueiros is being brought back into public awareness through the mural and lives on in the street art of a new generation of practitioners. The resurfacing of Siqueiros is part of an effort to build a collective identity for Chicanos and ensure they are seen and heard within the city. América Tropical’s local exhibition, combined with it winning the Silver Medallion award at the International Film and Television Festival in New York, heightened awareness of the mural and began the long campaign to restore the work of art and make it publicly accessible.

Treviño expanded upon América Tropical’s theme of historical recovery in Yo Soy Chicano (1972). The documentary took up questions posed by Rubén Salazar in his polemical February 6, 1970, Los Angeles Times column “Who Is a Chicano? And What Is It the Chicanos Want?” by presenting the histories of Chicano people from pre-Columbian times to the present.55 The film juxtaposes a past made out of archival photographs, maps, paintings, voice-over, and staged reenactments, with a present captured through verité-style footage shot by Barry Nye and Martín Quiroz. The structure serves a twofold rhetorical purpose. First, it declares that the Chicano civil rights movement is part of a hundred-year-long fight against dispossession and prejudice. For example, after a description of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the steady seizing of territory and refusal to honor citizenship rights, recent footage of Reies López Tijerina shows his determination to win back the New Mexico land-grant territories. Shots of Tijerina speaking at New Mexico Highlands University and West Las Vegas High School depict him as a charismatic and revered leader. At another point in the film, photographs that illustrate the plight of Central Valley migrant farm labor in the early twentieth century are juxtaposed with footage from United Farm Workers rallies and interviews with Dolores Huerta. She speaks proudly about the formation of the union in 1962, the strike of 1965, and the five-year Delano Grape Strike that ended victoriously in July 1970.

Second, Yo Soy Chicano demonstrates that culture is essential to how Chicanos understand themselves. The documentary traces a historical line from the art, music, and literature of postrevolutionary Mexico through to the Denver-based poet Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, author of the poem “Yo Soy Joaquín.” Even the film’s title song, composed and performed by El Teatro Campesino, is an adaptation of the popular corrido from the Mexican Revolution, “La Rielera.” Culture becomes a repository of collective memory and a way to sustain group identity across time and space. Critic Cecil Smith wrote that the film “would segue from the political and social situations here and along the Texas border towns . . . into the historical context, where the people came from, their presence on this land long before the Anglos took over.”56 Treviño told the Los Angeles Times, “In the schools, Chicanos are not taught their history, I really went into the historical experience in order to start filling in the gaps.” The documentary was first shown on KCET and around Los Angeles, including a community premiere at the new KCET studio. The film then played nationally.57

Treviño, together with Chicana activist and filmmaker Rosamaria Marquez, produced the public affairs series Acción Chicano (1972–74). The first episode took place at the impressive Plaza de la Raza, the recently constructed library, art center, museum, auditorium, and classroom space in Lincoln Park. The site was an accessible, mixed-use communal space for Chicanos, constructed by means of a combination of federal Model Cities funds and funds from organizations such as the East Los Angeles Community Union. Other Acción Chicano episodes included a profile of the Mexican American women’s organization Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional and a deliberation among Chicano professors about the struggle to establish Chicano studies at universities.

An important episode covered the first national convention of La Raza Unida Party. The event was held in El Paso September 1 through 5, 1972. The party was established in 1970 in Crystal City, Texas, as a deliberate alternative to the country’s two-party system, one that could directly serve the sociopolitical and economic needs of Chicanos. With electoral victories of local candidates, La Raza Unida expanded throughout Texas and into the Southwest and West Coast states. Movement luminaries Reies López Tijerina, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, and José Angel Gutiérrez convened a national convention to unify the party, establish a platform, and determine its leadership. Treviño was in charge of media relations for the convention and also documented its unfolding. The Acción Chicano episode depicted a debate among representatives about goals for the party and the prospects of cross-racial and transnational coalition building. The differences between Gonzales’s militant nationalism and Gutiérrez’s ambition to grow broad-based support were evident. The film also explored tenets of the party platform, backing the United Farm Workers Union, equitable salaries, school reform, the acquisition of land-grant territories, and maintaining an independent position from Democratic and Republican Parties. After Gutiérrez is elected party chairperson in an intense election, the film ends with a call for shared ethno-cultural identity and political purpose.

The African American filmmaker Sue Booker was another key member of KCET. Born in Chicago, Booker studied film, journalism, and creative writing at the University of Illinois. At Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism, she took classes with Fred Friendly and participated in campus protests. She graduated in 1968 and worked with Jon Stone and Samuel Y. Gibbon Jr. at the Children’s Television Workshop, developing what would become Sesame Street (launched in 1969). She then joined Nebraska’s public television station KUON for the series The Black Frontier (1969–70), which depicted the experiences of nineteenth-century black traders, soldiers, and cowboys.58 Charles Allen recruited Booker to KCET. Booker later recounted that she desired to “document the history and present moment of the African American people. Our lives were invisible and I wanted to make us visible, in all our beauty and dignity.”59 One of her first programs, Cleophus Adair (1970), concentrated on the problem of drugs in Watts. The documentary followed a reformed addict who went on to serve as a senior counselor at the House of Uhuru clinic and social services center. Both Adair and House of Uhuru were depicted as badly needed and much beloved by the community. Booker used Adair’s recorded voice as well as on-screen scenes of him giving an informal tour of the area to explore the sociological conditions that made Watts vulnerable to drugs.60 The documentary was nominated for a local Emmy.

Booker and Treviño’s collaborative project Soledad (1971) investigated California’s infamous Soledad State Prison. It was alleged that prison authorities had framed three African American inmates for killing a white guard. The prison was known for mistreating inmates of color, especially those who were politically outspoken. Booker, Treviño, and cameraman Barry Nye got permission to film inside the prison and were led by deputy warden Jerry Enomoto on a series of interviews with inmates on their way to parole. Distracting the prison authorities, the team managed to conduct on-the-fly interviews with inmates. Otis Tugwell spoke about the “hole,” a solitary confinement “prison within the prison” in which inmates were placed and sometimes found dead. Tugwell decried the racist mistreatment of minorities and censorship regarding the expression of leftist political opinions. In a heated moment in Soledad, a befuddled Enomoto is unable to respond to black inmate Chris Walker’s statements about racism in the facility. The documentary won first prize and a jury award at the Atlanta International Film Festival.61

Subsequently, Booker created a series of nationally broadcast, black-themed programs under the title Doin’ It! (1972). The series was broken down into nine episodes, with each installment lasting thirty minutes. The first show, the Emmy-nominated “Victory Will Be My Moan” (1972), examined the radical politicization of black inmates made to live in horrific conditions. In the program, actors dramatize the real-life experiences of incarcerated individuals. Big Man plays a self-taught revolutionary who tries to educate his fellow inmates. He shares a cell with a drug addict, an ex-hustler, and a newly arrived convict. For the soundtrack, the Watts Prophets perform poetry written by prisoners.62 Booker turned Doin’ It! into the locally broadcast series Doin’ It at the Storefront (1972–73). She insisted on having a studio in South Central, enabling the series to have a strong presence within the community. Booker set up a “storefront” studio at 4211 South Broadway. In an interview with Essence, she explained: “Because we’re regarded as a part of the community, people walk in off the streets with news stories for us. This aids us in presenting news that receives very little, if any, coverage in the general mass media. White media has a crisis coverage mentality and, therefore, ignores our daily lives and struggles, which seem minor but are really major events that lead to the changes of tomorrow.”63

The studio was a space from which to broadcast as well as a social destination. Booker encouraged people to drop in off the street to share story ideas. The studio was also used as a meeting center to discuss health, education, and arts outreach. With the facility’s open-door policy, Booker was able to formulate a community calendar. The series’ community coordinator, Agnes McClain, would read the schedule of upcoming events during each program. Booker also frequently appeared to introduce the topics of the program as well as the staff. This established an intimate rapport with viewers and signaled her investment in the lineup of topics. She even proudly introduced interns, whose labor is often invisible in the television industry. Journalist Maury Green wrote that the show’s embedded studio made it “more than a news bureau,” and that “Booker concerns herself with the things that matter to the black community.”64 The New York Amsterdam News called the concept “unique” because of how it functioned as a “community center as well as a news-gathering office.” Doin’ It at the Storefront directly tended to local needs. For example, Booker’s staff took families of inmates to California prisons for visits. John Outterbridge’s Compton Communicative Arts Academy gave Booker an award for her pioneering work in community engagement.65

The series’ episodes can be classified into three major clusters. The first focused on direct activism, which included events like the November 1972 strike at the William Mead public housing project or Angela Davis’s speeches against Richard Nixon’s attack on minority rights. The second looked at neighborhood culture, which included topics such as the Yo’ People rhythm and blues ensemble, Horace Tapscott’s Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, or Mayme Clayton’s Third World Ethnic Bookstore. And the third examined national debates that reverberated locally, such as illiteracy and blaxploitation cinema’s impact on spectators.66 The format for each individual program consisted of a mix of performances, interviews, speeches, and conversations. For example, “Soul Radio and the Black Community” (1973) described the creative skills and important function of black DJs. In the program DJs appear in their broadcasting booths like artists in studios. Their manipulations of the microphone, records, switches, and levers make for an elegant performance. The DJs comment on daily life, while also creating a soundboard for listeners to phone in and voice their opinions. The charismatic KGFJ DJ Magnificent Montague, whose signature shout-out was “Burn, Baby! Burn!” exclaims into the microphone and out to his listeners: “Put your hand on the radio and reach out and touch me this morning.” Or, in the beginning of the episode “The Church” (1973), Operation Breadbasket Choir sings “Go Down Moses” on a soundstage, before Booker appears in front of the camera to provide an introduction. She talks about the history of the black church in the United States as an establishment that upheld the humanity of its members and assisted in their ability to maintain a connection to their African roots. Paul Kidd Jr., who serves as the gospel DJ for KGFJ, then guides the viewer through a timeline of African American religious history. He begins with the Free African Society in the late eighteenth century, speaks about the role played by preachers in helping their congregations deal with the promise and disappointments of black freedom during Reconstruction, and affirms the importance of religious teachings to the civil rights movement. The show concludes by surveying contemporary nationalist perspectives on religion, for example Reverend Albert Cleage’s Black Christian Nationalism and Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam. The Operation Breadbasket Choir provides lyrical commentary on the history that Kidd narrates, at times singing hymns or gospel tunes such as “Steal Away Home,” “I Want to Be a Worker for the Lord,” or “Come, Let Us Walk This Road Together.” Booker’s series and stand-alone documentaries made black Angelenos more aware of themselves as possessing shared life experiences, cultural rituals, and sociopolitical concerns.

Lynne Littman was another essential Human Affairs member, creating a niche for herself in documenting the burgeoning women’s liberation movement. Born in the Bronx, New York, Littman studied French and philosophy with Susan Sontag at Sarah Lawrence College and spent her junior year abroad in Paris, where she developed a love for European New Wave cinema. After graduating from college in 1962, she returned to New York motivated to find employment in the film and television industries. She found opportunities for women extremely limited, but worked her way up from a secretarial position at WNET to jobs where she was directly involved in production. She became a photographic researcher for Wolper Productions and an associate producer for William Greaves’s series Black Journal (1968–78), the first nationally syndicated black public affairs show. She also crewed as an editor and associate producer on individual NET Journal documentaries. Diary of a Student Revolution (1969) investigated the University of Connecticut students’ opposition to on-campus recruitment by corporations. Some of the companies had connections to weapons being used in Vietnam. What Harvest for the Reaper (1968) explored the lives of migrant African American laborers in agricultural camps in Cutchogue, Long Island, where they picked beans for low wages and were housed in ramshackle lodgings.

The French filmmaker Agnès Varda recruited Littman to come to Los Angeles to work as an assistant on the art-house fiction film Lions Love (1969). Littman had met Varda at the New York Film Festival through their mutual friend and colleague, the Canadian cinematographer Guy Borremans. Littman would later recall heated conversations with Varda about the dynamic state of world cinema, the challenges to creating socially engaged art, and the need for more women directors. Lions Love looked at the antics of New York underground performers Viva, Jim Rado, and Jerry Ragni. They play struggling actors who spend much of their time in a house and backyard pool on St. Ives Street above the Sunset Strip. The trio tries on and takes off different identities: strung-out hippies, celebrities, a nuclear family with kids. The satirical performances poke fun at the artifice of the entertainment industry and the glamour associated with the health-conscious, affluent Los Angeles lifestyle.67

Littman found that she was interested in the lives of the city’s diverse inhabitants rather than in deconstructing the dream factory: “Journalism and documentary were different than fiction film. They were a way to really learn about the world . . . and in documentary, you find that everyday people have important, heartfelt things to say.”68 Determined to create her own films, Littman made UCLA-sponsored medical documentaries about drug addiction and counseling. With the formation of Human Affairs at KCET, she landed a job in public television. Her films advanced the cause of women’s liberation, demonstrating that “private” and “personal” issues associated with domestic life, the family, and the body were indeed public and political.

Littman was connected to Los Angeles’s National Organization for Women (NOW) chapter, which organized around gender equality in the workplace, increasing access to education and job training, as well as the expansion of childcare and maternity leave. Fighting for progressive legislation, participating in protests and consciousness-raising circles, as well as the fashioning of self-representations in the media were all important. In the Matter of Kenneth (1973) concentrated on the efforts of state officials to take a poor black child away from his mother due to charges of abuse, with lawyers advocating that they be allowed to stay together; Airwoman (1972) exposed the abuses suffered by airline stewardesses; Come Out Singing (1972) captured an in-studio performance by the feminist folk singers Holly Near, Cris Williamson, Margi Adam, and Meg Christian; Fortune in Singles (1972) chastised the parents who profited from a child’s acting career as well as other entertainment industry affiliates who made money from the labor of children; Power to the Playgroup (1972) profiled a much-loved playgroup that was being pushed out of its Silver Lake neighborhood facility because of a minor building violation.

Womanhouse Is Not a Home (1972) was Littman’s largest project of the period and most directly intersected with the creative endeavors of other feminists. The film focused on the seminal art installation and collaborative performance space Womanhouse, organized by artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. The documentary is an extraordinary record of the ephemeral installation and affirms the value of art as a community-building social practice. One of the motivating forces for Womanhouse was to create a space for female cultural production that could stand against a male-dominated art establishment. The same year that the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists protested the 1971 Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Art and Technology exhibition for excluding women from its roster, Chicago began one of the first feminist art programs at Fresno State College. When the administration insisted that she shut it down, she started the Feminist Art Program at CalArts in Valencia. With the new facility under construction, Chicago, Schapiro, and art historian Paula Harper planned an independent exhibition. They created Womanhouse with their students in a soon-to-be-demolished seventy-five-year-old mansion at 533 North Mariposa Street in Hollywood. Students transformed each of the seventeen rooms into a themed space that spoke to different aspects of the female experience. The artists deliberated together on the direction of each room.

Littman had met the artists of Womanhouse as well as one of the founders of the Feminist Art Program at CalArts, Sheila de Bretteville, through her participation in consciousness-raising circles hosted by individuals in living rooms across Los Angeles. Womanhouse Is Not a Home captures the themed spaces, performances that took place on the premises, and visitors’ reactions and conversations with one another. The documentary’s title announces that the “house” in which the art is exhibited is not simply a “home,” nor a traditional museum or a gallery. As the film makes clear, Womanhouse was intended to destabilize viewers’ assumptions about the separation between art and life, public and private realms of experience. After a piano performance by Debby Quinn in which she sings a ballad in praise of female independence, “Do You Think That It Would Matter,” Littman takes the viewer to the building’s front door. People walking in and out give their initial impressions. One woman says that men should definitely come to the exhibition, because they would learn a lot. Another says that it is a wonderful commentary on the female experience. A man’s gripe that Womanhouse should be “redecorated” appears as a condescending sound bite, diminished by the testimonies of praise that surround it.

Moving inside the house, longer interviews with the artists lend insight into their processes and provide an interpretation of each room. Vicki Hodgetts and Robin Weltsch discuss their Nurturant Kitchen, which features sunny-side-up eggs on the ceiling that slowly morph into rubber breasts on the walls. They talk about the room as registering the sense of angst and frustration with a woman’s domestic role, but also the sense of warmth women may feel within the space. Hodgetts and Weltsch share that their fellow artists urged them to think about representing food and the body together. In The Nursery, large furniture and androgynous dolls fill a room painted dark blue and red. Artist Shawnee Wollenman reflects on the idea that the room is designed to simulate the experience of being a child; however, the gender-neutral toys and decor subvert traditional gender norms.

Interwoven with the film’s tour of the different rooms are short performances. A silent Sandra Orgel irons a piece of fabric in Ironing, continuously repositioning and refolding the linen. The absence of any background noise, along with the unflinching camera, amplifies the sound of her ironing and focuses attention on the routine. The performance argues that domestic work can be a form of exacting, isolating, and monotonous labor. In The Birth Trilogy a group of women choreograph “birthing, mothering, and nurturing” as a series of stages. In a choreographed dance, they first simulate the act of giving birth to one another, before crawling toward and singing in one another’s arms. The shift in sound from the collective cry of “push” to the lullaby-like chant gives continuity to the performance. In Judy Chicago’s Menstruation Bathroom, a stark white bathroom contains shelves stuffed with wadded-up cotton and used tampons overflowing a trash can. The intention, as Chicago indicates, is to call attention to the contrast between the public fantasy of women’s bodies as “sanitized” and “pure” and their actual experiences. Menstruation is often not talked about, but rather treated as invisible or taboo. The installation foregrounds a sense of frustration with women feeling as though they must keep themselves hidden behind literal and symbolic closed doors, and the desire to make visible the facts of the female body.