5

Wattstax and the Transmedia Soul Economy

The action itself is the art form, and is described in aesthetic terms: “A very imaginative deal,” they say, or, “He writes the most creative deals in the business.”

—WRITER JOAN DIDION, 19731

I enjoyed every bit of Wattstax. The people were being themselves, and I felt like I was there in the movie. Some parts of it just brought tears to my eyes because it was so beautiful.

—MOTHER IN CHICAGO, 19732

When the soul music label Stax Records joined forces with Wolper Productions to make a documentary about the concluding concert of the 1972 Watts Summer Festival, the result was no ordinary concert film. The event in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum consisted of a showcase of Stax artists, including Isaac Hayes, the Staple Singers, Albert King, and Rufus and Carla Thomas. The 112,000 attendees, most of whom were black, were eager to see many of their favorite performers and to participate in the festival’s larger effort to commemorate the 1965 Watts Uprising. Making a film about a concert that honored a street protest was a particularly complex undertaking. The documentary brought together a wide-reaching cast of characters. Stax executives Al Bell, Larry Shaw, and Forest Hamilton supplied the musicians for the show and retained editorial control over the documentary. Wolper Productions’ David Wolper and Mel Stuart coordinated the filmmaking operations. Up-and-coming comic Richard Pryor provided the narrative commentary. And neighborhood residents appeared as interviewees in front of the camera and, in some cases, helped shoot the event.

For years Wattstax was treated as just a minor episode within the rise-and-fall story of Stax, but recently, increasing interest in comparative media studies and cultural histories of Los Angeles has led to a flurry of scholarship on the film. Interpretations of the documentary sort into three general positions. The first contends that Wattstax was a fresh way to display the record label’s talent, but that the project failed to successfully launch Stax into film.3 The second maintains that Wattstax documented creative stylizations of black experience that spoke to a sense of self-respect and optimism for future prospects in Los Angeles.4 The third argues that the documentary aimed to present a non-stereotypical view of Watts, but that its financial imperatives and its romantic depictions of the area distanced it from both the communities it ostensibly sought to represent and the audiences it sought to reach.5

These three interpretations have either under-theorized the role of the film’s different players or overemphasized their profit motive. Only through analyzing Wattstax as a collaborative project can we understand the full scope of the film’s economic and social ambitions. This approach also makes evident the increasing intersection between disparate figures and institutions in the film, television, and record industries during this period, and highlights the ephemeral nature of these partnerships. The distinct efforts of Stax, Wolper Productions, and local filmmakers and residents enabled the documentary’s innovative exploration of black cultural nationalism. Drawing on, but adamantly differentiating itself from popular black action features and concert documentaries, Wattstax portrayed music as an empowering language of individual and collective expression, connecting the performances heard in the coliseum to the social landscape of the surrounding neighborhood. The documentary’s multilayered approach to black music made penetrating the commercial market difficult, but ultimately led to its positive reception in black communities.

GROOVING WEST

The concept for Wattstax grew out of the Watts Summer Festival, which began in August 1966. As historian Bruce M. Tyler has written, organizers intended for the festival to commemorate the uprising the year before, but were more invested in celebrating black creativity and increasing access to social services than advocating for another mass protest.6 Key planners included Tommy Jacquette, founder of Self-Leadership for All Nationalities Today (SLANT), Maulana Ron Karenga, leader of the US Organization, and Booker Griffin, prominent radio commentator and newspaper columnist. Reflecting the festival’s cultural-nationalist goals, participants showcased present-day folkways as well as African heritage by means of music, art, and dance. Six blocks of 103rd Street as well as Jordan High School became home to entrepreneurs, outreach organizations, a jazz festival, and a parade. The Watts Happening Coffee House served as a theater and music venue. In its first editions, the festival occasionally became a site of violent contestation. Attendees clashed with police, who were against the idea of honoring the uprising.7 So too did organizers clash with militant radicals, who claimed that the festival was an escapist carnival with no direct political effect.8 Still, the multiday event sustained momentum and gained greater visibility with each year.

Stax saw the creation of a concert and an accompanying film at the 1972 festival as the culmination of a recent period of transition. Stax had shifted significantly since 1957, when the white record producer Jim Stewart started the small company in a recording studio in Memphis’s Capitol Theatre. By the late 1960s, Stax was a large organization intent on diversifying, expanding its roster of artists, and cultivating a more socially conscious image.9 The black producer Al Bell became Stax’s creative compass and guided the label through this period of change. Bell had worked as a student teacher with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta and as a DJ and record producer in Little Rock and Washington, DC. He was drawn to the intellectual and affective power of music to move listeners. Bell joined Stax as the national promotions director in 1965 and advanced to vice president in 1967. By the turn of the decade he was a co-owner and by 1972 the sole owner.10

Artists drew inspiration from the cultural milieu of the Mid South Delta region in which the company was founded. Stax’s unofficial name, “Soulsville U.S.A.,” pointed to the label’s secularization of sacred black music traditions. Artists combined the call-and-response patterns and “vocal freedom” of gospel with the musical virtuosity, danceable tempo, and storytelling of rhythm and blues.11 The name also gestured toward the label’s passion for capturing raw performances rather than highly produced routines. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis and the concomitant rise of the Black Power movement were important to Bell’s ascent within Stax and inflected the company’s expansion. Stax hired more black advertising, marketing, and secretarial personnel. Artists backed health care and educational initiatives in minority communities. Bell supported artists as their songs began to directly embrace themes of black empowerment and looked to build musical bridges between American and African composition. New subsidiary labels that featured John KaSandra’s raps and Jesse Jackson’s popular litany “I Am Somebody” were marketed to schools and churches.12

It would be plausible to see the label’s expansion as dovetailing with President Richard Nixon’s support of “black capitalism.” In the months leading up to and immediately following his 1968 presidential campaign, Nixon vocalized his support for “more black ownership, for from this can flow the rest—black pride, black jobs, black opportunity and, yes, black power.” He went on to stress, “What is needed is an imaginative enlistment of private funds, private energies and private talent.”13 However, as historians Laura Warren Hill and Julia Rabig argue, the “business of black power” was a topic of debate long before Nixon began using the phrase to co-opt black militancy for a Republican Party platform and to woo liberals and minorities from the other side of the aisle. Black economic empowerment included a wide range of positions: Earl Ofari Hutchinson’s critique of capitalism as essentially racially and economically exploitive; Andrew Brimmer’s assertion that a separatist black economy could not be sustained within the realities of the market; publications such as Essence supporting blacks in leadership positions in major corporations; James Forman’s demand for reparations for slavery; and Stokely Carmichael’s proposal of co-op business models in which community members have a stake and the profits go back to the community.14 While Stax was not a grassroots organization, it also was not an entirely profit-driven corporation. Bell saw minority empowerment as something that required collective effort and social benefit. It could not be simply achieved by individual drive and the free market. Aligning Stax too closely with Nixon’s pronouncements obscures the complexity of the organization and the relationship between the label, its projects, and its multiple audiences.

One of Stax’s central goals was to build a profile in motion pictures. The company’s sale to Gulf and Western in 1968 was motivated by the prospects of working with the conglomerate’s film subsidiary Paramount Pictures and setting up a studio in Los Angeles. The films Stax artists worked on in the late 1960s and 1970s did not coalesce around a particular view of race relations or a conception of a new black cinema. In fact, the white auteur Jules Dassin’s black-cast film Uptight (1968), the black artist Melvin Van Peebles’s independent production Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), and the black commercial photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks Sr.’s studio feature Shaft (1971) clashed with one another ideologically and inspired differing criticism and praise. All these productions nonetheless explored post-1968 racial politics and rejected the liberal integrationist “social problem” film. Stax saw the soundtrack as a new vehicle to promote its music, an imaginative medium for its artists, and a commercial product in its own right. The label also sought to rival Motown, its main competitor. Motown president Berry Gordy had recently expanded his Detroit-based pop–R&B label to Los Angeles, hoping to showcase its stars in both television variety programs and feature films.15 Motown was known to the country as “Hitsville USA,” and the Motor City label’s sound—characterized by a clean, smooth balance between vocals and instruments along with catchy melodies—appealed to a crossover teenage audience. Los Angeles Magazine declared that Gordy was creating a “commercial empire” in Hollywood.16

For the Paramount film Uptight, Stax’s leading session musician Booker T. Jones composed the score and performed it with his MGs ensemble. Uptight focuses on Tank Williams (Julian Mayfield), a black ex-convict and former steel mill employee living in Cleveland. Distraught by King’s assassination, Tank is unable to join his fellow radicals on an arms raid. His absence causes hiccups in their plan and the police pursuit of the group’s leader, Tank’s close friend Johnny Wells (Max Julien). Ostracized by his friends for refusing to join them, Tank becomes a police informant, which results in Johnny being killed by lawmen. Tank’s guilt-ridden wandering through the streets of Cleveland concludes with his death at the hands of his former friends.

Booker T.’s compositions are overtly intertwined with the on-screen action. The ballad “Johnny I Love You” plays at the film’s opening against a series of watercolor paintings assembled in storyboard fashion. The impressionistic images show an adolescent Tank and Johnny playing on the streets of Cleveland. The lyrics speak to Tank’s affection for Johnny as a brother and also communicate a shared desire to “fix” a city that “ain’t right.” The optimism conveyed by the song is quickly ruptured by the immediate transition to documentary footage of King’s funeral cortege on the streets of Atlanta, and reenactments of street protests by black crowds in Cleveland. It is as if nonviolent resistance and the desire for integration exist in the past, unable to confront the realities of the present.

“Time Is Tight” plays at the film’s conclusion during the chase scene when Tank first runs from, and then tries to attract, the attention of his former friends. The driving electric guitar and drums charge the scene with nervous energy, but the transition to the slow wail of the organ creates the feeling of a funerary dirge as Tank hangs from a crane and then drops to a pile of dirt and iron ore below—laid to rest in the mill where he had worked for twenty years before being fired.

The success of Uptight’s soundtrack motivated Stax to pursue film opportunities and soon after to take a major role in distributing Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song as well as its accompanying album.17 The story follows Sweetback (Van Peebles), a black orphan turned sex show performer who is arrested on a bogus charge. He escapes his captors by beating them with his handcuffs before they kill a Black Panther. Sweetback then spends the rest of the film running from the law and making a narrow escape across the border to Mexico. Sweet Sweetback’s “musical pastiche,” according to historian Amy Abugo Ongiri, involves gospel, spoken-word performance, African-style drumming, and the funk stylings of Earth, Wind & Fire.18 In the book The Making of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, Van Peebles wrote that he wanted to experiment with sound to “help tell the story.”19 Free jazz playing against the contrapuntal editing sets a fast-paced tempo for Sweetback’s flight across train yards, freeways, pump fields, and the Los Angeles River. Van Peebles’s voice-over raps, interwoven with the soundtrack, comment on Sweetback’s physical and mental state as he fights exhaustion, injury, and the police. Stax’s vice president of publicity, Larry Shaw, handled the targeted distribution of both the film and the soundtrack to black audiences in major cities. Viewers could even buy the LP in theater lobbies.20

Shaft would come to be the most visible Stax-related feature film. MGM commissioned Stax artist Isaac Hayes, who had recently achieved worldwide popularity with his album Hot Buttered Soul (1969), to do the music. The film tells the story of John Shaft (Richard Roundtree), a black detective working out of Harlem. Black gangster Bumpy Jonas (Moses Gunn) commissions Shaft to find his kidnapped daughter Marcy (Sherri Brewer). Bumpy deceptively leads Shaft to collaborate with the black militant Lumumbas, of which Shaft’s old friend Ben Buford (Christopher St. John) is a member. Together they fight the downtown Italian mafia, who are trying to muscle in on Bumpy’s illegal business dealings, and rescue Marcy. As in Uptight and Sweet Sweetback, the soundtrack plays a key role in character development. Starting with the opening credits, the music of Hayes and the Bar-Kays establishes the personality of the protagonist as a man of action. Sixteenth notes played on the hi-hat cymbal are in sync with Shaft’s steps as he emerges from a subway station in midtown Manhattan. Recurring wah-wah-pedal guitar riffs, strings, and horns set a fast pace for Shaft’s purposeful strides. He swiftly moves past pedestrians and weaves through oncoming traffic.

The critical attention to and high box office returns of Sweet Sweetback and Shaft, along with recently released films such as Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), led to a deluge of studio-made black action features. Set in inner-city locales, these films typically center on black male detectives, vigilantes, and gangsters seeking retribution, revenge, or order—in opposition to a white villain. At a time when major studios were desperately trying to stave off declining theater attendance, films targeting black viewers were beginning to be considered a significant revenue generator. For much of the classical era, studios had written off trying to explicitly court minority viewers. Hollywood’s shift toward black action features was also a response to pressures to create professional opportunities for African Americans and to represent a greater breadth of black experience on-screen. Newsweek announced a veritable “Black Movie Boom,” and the Black Arts magazine Black Creation declared that there was an “explosion” of black cinema.21 Warner Bros.’ Super Fly, Paramount’s The Legend of Nigger Charley, American International Pictures’ Blacula, and MGM’s Melinda and Cool Breeze are just a sampling of the films that came out in 1972. The cycle’s popularity stemmed from its foregrounding of strong black characters who proudly challenge white authority, the involvement of black personnel in the production process, on-location shooting in black communities, and nationwide distribution to black audiences.

Still, critics offered scathing reviews of these films. Claiming that they were a form of “black exploitation,” Junius Griffin led the Los Angeles–based Coalition Against Blaxploitation, which criticized the cycle for promoting negative stereotypes and primarily benefiting white Hollywood power brokers.22 Without weighing in too heavily on specific debates regarding the plots or themes of the films, Stax’s Al Bell voiced his support for the individuals working on the productions. In a front-page Billboard article he stated that Sweet Sweetback and Shaft were valuable because they involved black artists coming together to work collaboratively: “A major film with a black director, a black star and a sound by a black composer . . . is an enormous source of pride to the black community. It’s more than just a movie—it’s a special event.”23 In its future endeavors, Stax would forgo trying to replicate Shaft’s success, focusing instead on creating an alternative kind of community-focused cinema.

THE STAX-WOLPER ALLIANCE

Jim Taylor and Richard Dedeaux of the Mafundi Institute approached Forest Hamilton with the idea of Stax staging a concert to conclude the Watts Summer Festival. Mafundi was a local cultural-nationalist arts space and social service center on 103rd Street. It had been a crucial contributor to previous festivals. Hamilton had worked in film distribution and as an entertainment and sports promoter before helping to establish Stax’s Southern California satellite, Stax West. Eager to migrate Stax’s music across media, Hamilton developed the concept of filming the show. Bell loved the idea. The Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company agreed to serve as a sponsor, the artists agreed to play for free, and Stax decided to charge only one dollar per ticket. The proceeds would go to the Martin Luther King Jr. General Hospital, the Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation, and the Watts Labor Community Action Committee.24 Giving the concert a celluloid afterlife would project the sounds of Stax much farther than the coliseum’s loudspeakers. This strategy would also guarantee access to black communities as well as white liberals, college students, and the art cinema crowd. Importantly, Stax anticipated that Wattstax would provide a strong counterpunch to what the Los Angeles Sentinel described as the “Motown Entertainment Complex.”25

When Bell sent Hamilton to find the “very best documentary producer,” he went to see David Wolper, who signed on for the film.26 Beyond the jazz background of one of Wolper Productions’ main directors, Mel Stuart, the studio possessed three highly desirable qualities that made it the ideal choice for Stax. First, Wolper Productions had been making an eclectic range of documentaries for more than ten years—everything from historical compilation films about military conflicts to verité-style portraits of politicians. Second, Wolper Productions was based in Los Angeles and consistently worked with different talent pools. Observational filmmakers such as D.A. Pennebaker, Richard Leacock, or the Maysles brothers were well known for documenting musicians, but they were based in the Northeast and lacked familiarity with Los Angeles; further downsides included their strong auteurist sensibilities, resistance to exposition in their films, and distaste for working within large organizations. Third, Wolper Productions knew how to cover large affairs. Recently the studio had collaborated with the Olympic Committee, the Bavaria-Geiselgasteig organization, and eight international directors to create Visions of Eight (1973) about the Munich Games.27

Wolper Productions had much to gain from the partnership. The studio had made documentaries that addressed race relations since the early 1960s, but was looking for the chance to create a new kind of film that could directly engage with minority viewers. Wolper’s Biography of a Rookie: The Willie Davis Story (1961) and The Rafer Johnson Story (1961) were nonfiction television analogues to the civil rights–era Sidney Poitier features such as All the Young Men (1960), Lilies of the Field (1963), and To Sir, with Love (1967). Through the optic of sports, Wolper’s television documentaries presented black Angelenos achieving an equal place in American society by means of hard work, individual performance, and integrated team play. Later in the decade, Wolper believed that adapting novelist William Styron’s self-labeled “meditation on history,” The Confessions of Nat Turner, would be a progressive undertaking. Ultimately his attempts to make the adaptation revealed major ideological tensions between liberal Hollywood and the Black Power movement. Black entertainers and intellectuals alike objected to the film’s racist source text as well as the film’s lack of black labor both below and above the line. The production never made it past the planning stage. But working on the project made Wolper and his circle more conscientious about the history of race prejudice and the contemporary black struggle for self-determination. They had also become eager to reach minority viewers, and knew that films that focused on African Americans needed to directly involve the people being represented.

Although Stax and Wolper Productions were confident about filming the Wattstax concert, they were unsure about the best way to build a film around the performance. By the late 1960s, concert documentaries had emerged as a popular film subgenre and provided a possible model. Monterey Pop (1968) and Woodstock (1970) were extensions of their respective festivals’ commercial initiatives and, as film scholar Keith Beattie argues, registered the immersive experience of attending the show.28 Soul to Soul (1971) also provided food for thought. The documentary depicted a concert in Ghana’s Black Star Square in Accra on the fourteenth anniversary of the country’s independence from Britain. R&B artist Wilson Pickett, beloved in Ghana, headlined the festival, and Ike and Tina Turner, the West African Kumasi Drummers, and Amoa Azangio were part of the lineup. An advertisement for the film read, “America to Africa: Where It All Came From/Bonds Tightly Tied—Musical Fire—Sound to Sound—Soul to Soul.”29 Much of Soul to Soul captures the ecstatic fifteen-hour, all-night concert. Brief cutaways highlight the American artists’ enthusiastic reception at the Kotoka Airport and their visits to the nearby village of Aburi and the Elmina slave castle.30

Stax and Wolper ultimately wanted to pursue a different kind of documentary, one that cogently addressed the relationship between music and social context. The Wolper Productions in-house director Mel Stuart, in particular, felt that films like Monterey Pop were overly “simple” and “boring,” akin to a basic newsreel. He told Forest Hamilton, “I don’t do newsreels.” In his estimation, the documentary would need to have a strong expository aspect.31 Stax and Wolper resolved to interweave concert footage with interviews and observational scenes of South Central, emphasizing the association between the performances on the bandstand and people’s everyday lives.

An eclectic mix of personnel and institutions signed on to help create Wattstax. Columbia Pictures handled distribution, ensuring a wide release. Despite having recently distributed a series of money-making, award-winning films, including the New Hollywood road movie Easy Rider (1969), the studio was in financial trouble at the turn of the decade. Its attempts to diversify into television, radio, and real estate coupled with poor box office returns on its recent roster of films had put it in the red.32 Mel Stuart agreed to direct the movie. He, along with producers Hamilton and Shaw, recruited the film’s black crew from the immediate area. Many came from universities and arts organizations.33 Included in this group were Larry Clark and Roderick Young, both of whom were involved with the L.A. Rebellion film movement around UCLA. Clark had worked with Charles Burnett on what would become Killer of Sheep (1977). Young had crewed on the Hollywood black action feature The Final Comedown (1972) and exhibited his nonfiction photography at the Los Angeles Festival of the Performing Arts. The Mexican American cinematographer John Alonzo was hired as a cameraman. His lyrical pans and sweeping tracking shots in Vanishing Point (1971) and Sounder (1972) had made him a noteworthy New Hollywood technician.

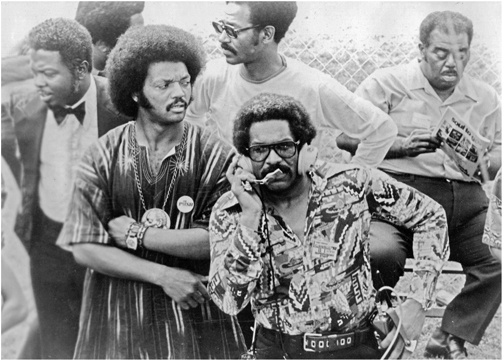

FIGURE 15: Jesse Jackson and Larry Shaw, publicity photograph for Wattstax, 1973, 35mm; directed by Mel Stuart; produced by Stax Records and Wolper Productions; distributed by Columbia Pictures. Courtesy of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music Archives.

Wolper Productions coordinated production, but Stax assumed editorial control over the content. This was a contractual move that separated Wattstax from many studio pictures of the time. According to Clause 2.4 of the contract, Stax would

have the absolute right of prior approval of film or narration which is included in the Picture which relates to Black relationships and feelings; words or phrases having a special Black connotation; and, if the Picture has a narrator, approval of the narrator and the accuracy of the narration script as to the music contained in the Picture. You [Stax] shall have the right of reasonable approval of the writer of the narration script, and you [Stax] agree to exercise said right in good faith.34

Comedian Richard Pryor joined the film to serve as a one-man Greek chorus. Stuart recalls that when Hamilton took him to see Pryor perform at the Summit Club on La Brea in Baldwin Hills, “within three minutes I knew that he was the greatest comedian of our time.”35 Pryor played Billie Holiday’s endearing, reserved piano player in Motown’s Lady Sings the Blues (1972). Now performing as himself in Wattstax, his barbed quips supplied the connective tissue holding the film’s disparate elements together.

COMMUNITY PORTRAITURE

Wattstax’s polyvocality is grounded in three kinds of performance: Stax artists on the bandstand; South Central residents on steps, sidewalks, cafés, and barbershops; and Pryor backstage at the Summit Club. Together, they establish how everyday life and music are in dialogue, each influencing the other. The film consciously aims to document the self-presentation and self-narration of both residents and artists, showing that performativity is integral to both informal interactions and formal, aesthetic expression. The film opens with Pryor seated against a solid black backdrop. Speaking directly to the viewer, his prefatory statements convey that the concert is a political act of commemoration. As the camera slowly zooms in on his face, he explains:

All of us have something to say, but some are never heard. Over seven years ago, the people of Watts stood together and demanded to be heard. On a Sunday this past August in the Los Angeles Coliseum, over one hundred thousand black people came together to commemorate that moment in American history. For over six hours the audience heard, felt, sang, danced, and shouted the living word in a soulful expression of the black experience. This is a film of that experience, and what some of the people have to say.

Pryor’s comments direct the viewer’s attention toward the people of Watts who protested together in 1965 and the crowd that gathered at the coliseum seven years later. What happened in Watts, Pryor states, was not a casual occurrence or haphazard act of violence, but a historic occasion of a people “demand[ing] to be heard.” The Watts Summer Festival honored the sounding of grievances through a contemporary assertion of visibility and voice. In turn, Wattstax was an effort to keep the significance of past actions alive and relevant. Participants were not simply on the receiving end of a message; they were agents in creating an event that resonated with the cultural vibrancy of their community.

A quick cut transitions from the darkened interior of the Summit Club to the Watts Towers. The sculptural mass of concrete-wrapped steel, inlaid with fragments of porcelain, glass, and tile, stands tall near the intersection of 107th Street and Graham Avenue. The title “Wattstax” appears in the foreground. A screeching wail cries out as a handheld camera glides down one of the spires. These shots give way to a montage of neighborhood views, playing against the Dramatics’ 1971 hit “Watcha See Is Watcha Get” on the soundtrack: “But baby I’m for real / I’m as real / as real can get / If what you’re looking for is real loving / then what you see is what you get.” The song goes on to accompany images of small children playing in a vacant lot, a mailman making deliveries, women waiting to board a city bus, a young couple in a romantic embrace, and teenagers walking to school, holding books. Images of Charcoal Alley ablaze from the 1965 uprising conclude the sequence.

As Wattstax takes the spectator into the coliseum, the concert is an occasion to reflect on the uprising as well as on the social dimensions of music. Framed in a medium shot on the bandstand with periodic cutaways to close-ups and overhead views of the crowd, Reverend Jesse Jackson is the first to address the audience before the show begins. He proclaims, “All of our people got a soul, our experience determines the texture, the taste, and the sound of our soul.” Performing this sentiment in song, Kim Weston’s rendition of the black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” speaks to the centuries-long fight for black liberation. Originally written by James Weldon Johnson, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was first publicly performed by schoolchildren on the occasion of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, 1900. Weston’s 1968 recording inspired renewed enthusiasm for the anthem as an emblem of self-determination and unity.36 In Wattstax, the song speaks evocatively to the contemporary moment as a time of possibility but also of great challenge. The position of strength from which Weston sings seems shared by the crowd. Whereas people remain seated and look distracted and bored during the singing of the “Star-Spangled Banner,” they stand proud for “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” elevated to their feet by the words and melody. The song then travels out of the diegetic context of the coliseum to serve as the soundtrack to a sequence of photographs and archival footage. The sequence includes an illustrated diagram of the slave ship Brookes, images of African Americans working in the field as sharecroppers during Jim Crow–era segregation, short newsreels depicting civil rights sit-ins, and brutal confrontations between black protestors and white police. Images of Frederick Douglass, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, Dr. King, Huey Newton, and Angela Davis surface throughout the still and moving images.

The sequence eschews a straight chronology of events or a simple, streamlined narrative of progress. It foregrounds the leaders who have in distinct ways fought for collective empowerment by means of leading boycotts, staging public sit-ins, waging legal battles in the courts, crafting political art, penning philosophical texts, or meeting the threat of violence with physical force. The sequence encourages viewers to see connections rather than differences among the leaders’ social actions. The images reference the struggles that the song narrates. At the concert, the 112,000-strong gathering of black people freely expressing themselves was heralded by festival organizers, attendees, and journalists as an achievement in itself. The peaceful happening proved wrong racist law enforcement officials and municipal leaders who thought so large a gathering would either not materialize or would result in violence.37

Alternating scenes depicting local citizens’ heated discussions about the meaning of the uprising and the current state of life in Watts take up the ideas raised during the anthem. In a scene in a store portraying a group of three friends debating the effects of the rebellion, one man comments, “It did something constructive for the whole community,” and another person chimes in, “They’ve opened up a Dr. Martin Luther King Hospital; and there are more black people in Watts who were formerly on county and state aid employed right now.” In a conversation in a café with a different group of people, one man states, “Up until the point when we had a riot, everybody said ‘those niggers are all right, they’re doing fine’; when we had a riot, the white man said ‘something’s wrong, because these suckers are burning down my store, I better give them something because I thought they were happy.’”

But just as some viewpoints affirm that the uprising has engendered constructive change, others appear dubious. Some comment that the recent addition of a handful of new facilities provides an image of progress that is shortsighted and illusory. One elderly man interviewed claims that neglect and corruption are still prevalent. Another man confidently states that the rebellion “changed some for the best, an awful lot of cases for the worse, and some, it has not changed at all. There is no difference in Watts now, from Watts ’65.” Filming individual testimonies communicates residents’ hopes and anxieties about the future of Watts, but obscures the implications of broader economic and political forces that were shaping post-’65 daily life in the area: the increasing government crackdown on militant organizing; infighting among Black Power leaders; increasing industrial relocation to the South Bay and outlying suburbs; and the prospective electoral victory of the city’s first black mayor, Tom Bradley.

And yet, Wattstax is more intent on capturing the persistence of a post-’65 sense of love and pride residents feel for a shared expressive culture. The documentary demonstrates that black identity and music are mutually constitutive. For example, artist Rufus Thomas’s invitation to the crowd to come “Do the Funky Chicken” signals the power of the music to create its own form of social space. Clad in a hot-pink cape, shorts, and go-go boots, Thomas shimmies, sings, and struts on the bandstand while members of the audience swiftly move from their seats to the field. Grooving concertgoers transform the coliseum into a grand outdoor dance floor, performing the steps to the “Funky Chicken” in a seemingly infinite array of styles. In both long shots of the crowd and close-ups of men and women, adults and children, the camera captures the collapsing distance between artist and audience, fan and celebrity. Each is ecstatically feeding off the energy of the other, coauthoring the concert, and relishing the cinematic spotlight.

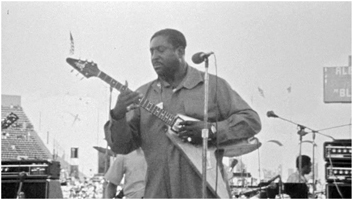

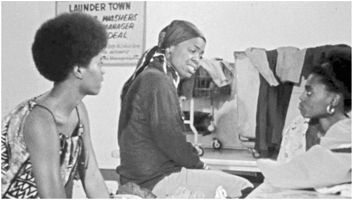

FIGURE 16: Still from Wattstax, 1973, 35mm; directed by Mel Stuart; produced by Stax Records and Wolper Productions; distributed by Columbia Pictures. DVD, Warner Home Video, Burbank, California, 2004.

FIGURE 17: Still from Wattstax, 1973, 35mm; directed by Mel Stuart; produced by Stax Records and Wolper Productions; distributed by Columbia Pictures. DVD, Warner Home Video, Burbank, California, 2004.

Moving from inside to outside the coliseum, guitarist Albert King’s performance of “I’ll Play the Blues for You” plays against a series of conversations showing how the blues gives form to personal and communal lament. Gazing out at the crowd as his fingers dance on the neck of the guitar, King announces that the song is “dedicated to all of the blues lovers, and to all those that aren’t hip to the blues, we’re going to learn them to you, teach them to you, rather, because we’ll be around for a while.” Shots of King playing are interspersed with interviews that show people’s familiarity with the blues. Men and women talk about the blues as something that “people can relate to right now, not tomorrow.” They wax poetic about the blues as a melancholic sentiment and a way to convey unrequited love and frustration. Their discussion often swings out to engage the generalized condition of feeling low and depressed. King sings: “If you’re down and out and you feel real hurt / come on over to the place where I work / All your loneliness, I’ll try to soothe / I’ll play the blues for you.” One man states, “I’ve been down so long, that getting up hasn’t even crossed my mind.” Another relates the blues to being by yourself on the street at night alone, and yet another says that the blues are like “an old car, man, that keeps stopping on you. This is what I’ve experienced with the blues, in many ways, not just with being in love.” A woman exclaims that the feeling of the blues is being left on your own with “your heart in your hand.” King’s worrying of the notes forms the instrumental counterpart to the speakers’ tremulous, impassioned voices. While the voicing of such sentiments often emphasizes singularity and loneliness, the sighs, yelps, laughter, and short responses from surrounding listeners give solace to the speakers, ultimately socializing the grief.

Other performances within the coliseum are interweaved with representations of and discussions about religion. When the Staple Singers take the stage to sing “Respect Yourself” off their 1972 album Be Altitude: Respect Yourself, they signal soul music’s connection to their gospel roots and stress its continued relevance. The family ensemble, like numerous Stax artists who grew up singing in church, did not abandon the sacred for the secular; they continued to draw on gospel instrumentation, lyrics, and performance styles in their music.38 In the film, the electric guitar playing of Roebuck “Pops” Staples, accompanied by the hand clapping of his two daughters, Mavis and Yvonne, begins the song: “If you disrespect everybody that you run into, yea / how in the world do you think anybody is supposed to respect you / If you don’t give a heck about the man with the Bible in his hand, y’all / just get out the way and let the gentleman do his thing.” The refrain is sung in unison by all three: “If you don’t respect yourself ain’t nobody gonna give a good ca-hoot, na, na, na, na / Respect yourself, respect yourself, respect yourself, respect yourself.” The song proclaims the need to treat others the way you want to be treated, a call for mutual respect that references scripture: “And as ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them likewise” (Luke 6:31). Pops asserts that “the man with the Bible in his hand” has a role to play in helping to spread this message of self-worth and mutual admiration for strangers and friends alike.

The Staple Singers embrace the call-and-response patterns of a preacher and congregation. Their repeated address to the listener as “you” and “y’all,” the imperative to “respect yourself,” and the between-the-verse phrases such as “help me y’all” strengthen their bond with the audience. Mobile, handheld cameras frame the family on the stage with their fans. Unidentified members of the audience, along with prominent black celebrities such as Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, appear enraptured by the music. They sing along, mouth the words, or tap their feet to the beat. Others stand up and dance in place. Then, the song serves as a non-diegetic accompaniment to shots of institutions in the neighborhood and in other centers for black life throughout the country. Shots of the Mafundi Institute in Watts, the Malcolm X College in Chicago, the Harlem Hospital Center, and the “Africa Is the Beginning” mural art from the YMCA Building in Roxbury, Massachusetts, illustrate what black power can achieve when people come together.

A photo montage portraying more than fifteen churches gives a sense of the presence of religion within black Los Angeles. The facades have different ornamental design schemes and signage, but all the churches appear heavily used. Many are storefronts or converted houses. The combination of two waves of black migration from the South and Midwest, along with the media resources of the city, made Los Angeles a destination for traveling gospel singers in the early to mid-twentieth century. Churches nurtured the music all over the city.39 In Wattstax, interviews with residents reveal that religious music puts people in touch with cherished memories. One woman recounts how listening to the gospel standard “Amazing Grace” is a ritual of familial remembrance: “When I hear the choir sing ‘Amazing Grace’ I start thinking about when my grandmother died, you know, she died of cancer. I was young, but the music just sets a thing.” A man talks about how church music provides him with an embodied emotional and spiritual charge: “When they [the choir and band] really get going, when they really get to jamming, I used to dig that, because you know, I’d be right there with them, and when people jump up and get happy, I’d jump up and get happy, too.”

A longer scene where the camera ventures inside a small church places viewers in a service. The Emotions’ rendition of “Peace Be Still” in front of a packed congregation speaks to the sentiments of the recent testimonies. With tight three-part harmonies, Sheila and Wanda Hutchinson and Theresa Davis raise the emotions of the crowd. They sing about how vigilance and faith can help people survive the most tempestuous of storms. Rocking in their pews, waving hands, fans, and scarfs, and calling out to the trio, the congregants are actively involved with the performance. Shots of the congregation echo those depicting the crowd in the coliseum. Both groups keep the beat with their hands and feet, hum or sing along with the music, and call out to one another and to the performers. Wattstax depicts the church and the coliseum as places that bring together family, friends, and strangers. The musical architecture of the songs heard within the physical architecture of the churches and the coliseum constructs complementary frameworks for community building.

Periodic cutaways to Richard Pryor in the same backstage space as his introductory address are woven between the music in the coliseum and the testimony of the residents. He riffs about law enforcement, gambling, religious rituals, nightclub culture, and alcoholism. Pryor’s intonation has a bop-prose quality. He moves at a frantic pace from anecdotes to declarations to one-man dialogues. He quickly changes the pitch, volume, and intensity of his voice as he impersonates white police officers, his parents, a drunkard, and a younger version of himself. Humor offers both a shield and a sword, an armor that allows one to laugh to keep from crying. Pryor weaponizes humor to impugn police brutality, racial discrimination in the workplace, and class privilege. His impromptu monologues are a way to combat the kinds of traumatic experiences associated with racism and economic disparity that preceded the uprising and continue within Watts.

His jokes about the intricacy of Black Power handshakes and devout religious faith are also meant to open up a space for reflection. They show how social practices work to build solidarities, but also indicate that these same practices can separate and alienate individuals from one another. As the cultural historian Scott Saul argues, Pryor’s role as “trickster-in-chief” at once “hedges the film’s political militancy and deepens it: hedges it in that he holds up the movement itself for mockery; deepens it in that his comedy reveals a movement capable of self-satire, willing to laugh at the games that ideology plays.”40 Pryor’s monologues, together with the interviews with Watts inhabitants and observational shots of Stax artists, also deepen an understanding of the entangled relationship between cultural forms and daily life. Just as music has a community-building function within the film, Stax and Wolper Productions wanted Wattstax to serve a community-building function for black audiences. They also saw this targeted release of the documentary as coinciding with the attempt to package and distribute the film to a larger crossover audience.

MULTIPLE PROJECTIONS

Members of Stax and Wolper Productions worked with several affiliates to develop a twofold plan of exhibition. First, they executed a focused release in black communities, crafting a socially conscious lens through which viewers would watch the documentary. Larry Shaw told the journal Black Creation, “We wanted to bring the same sensitivity to our post-production activity that we used in putting the film together.”41 Hiring the black marketing firms Communiplex (Memphis/Chicago), Communicon (Chicago), Cherrytree Productions (New York), WMS Associates (Washington, DC), and Z-J Associates (Philadelphia) was instrumental to the film’s niche advertising and exhibition within cities. Second, the team cultivated an aura of artistic merit around the documentary designed to excite critics and attract white liberals, college students, and the counterculture. Columbia Pictures launched a campaign for a wide theatrical and international film festival release. Shaw outlined in a letter to Columbia’s Robert Ferguson and circulated to Wolper, Bell, and Hamilton that the advertising and outreach should concentrate on both black and white moviegoers. The musicians themselves would assume the role of ambassadors for the film and would appear at select screenings.42

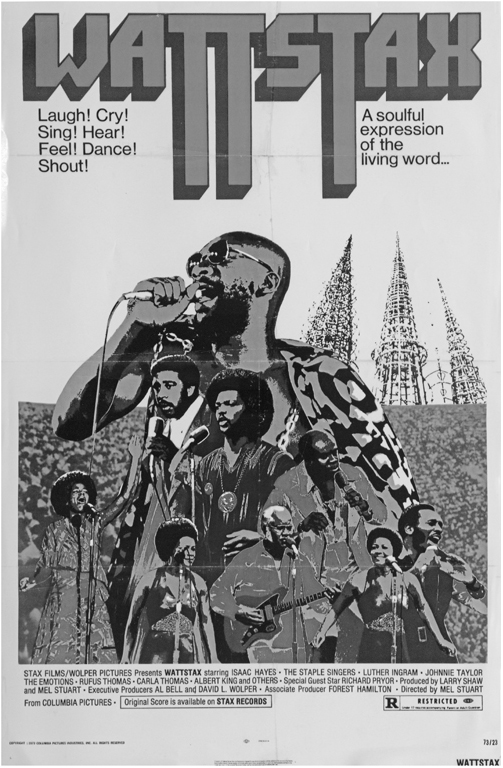

Articles about Wattstax’s production history, along with preview screenings tied with fundraising, community organizing, and nonprofit organizations, fueled anticipation for the film’s world premiere at the Ahmanson Theatre in the Los Angeles Music Center on February 4, 1973.43 Advertisements featured the documentary’s artists organized into a pyramid of talent with banner title “Wattstax” in sharp relief. Pittsburgh Courier journalist Larry Grant Coleman applauded the documentary’s ability to connect the music to daily life as something that a nationwide black audience could identify with:

The issues they discussed were the blues, the changes of love, politics, unemployment, economics, dope, prison and a thousand more. . . . We heard the plaintive and celebrating music of the best of contemporary black artists—and the music again brought to us, the message of the people. It forces us to understand clearly that the music of black people is more than mere entertainment bound up into a few rhythmic arrangements. That is, our music is really a pattern (a mosaic) of our lives and it weaves and bobs and changes as we do.44

Los Angeles Sentinel entertainment editor Gertrude Gipson noted the involvement of black personnel and commended the film for “immortalizing not only those who came to perform, but, also, those who came to witness the event and those who live in the communities of which Watts is symbolic.”45 Ruth E. Donelson, who had won the “Send a Mother to the Wattstax World Premiere Contest” when it was previewed in Chicago for a gathering of black mothers, said, “To me, Wattstax is a family movie that I recommend to all mothers. Though some people may not like some of the language, it is a part of everyday life, and even a part of the beauty of Black people living.”46

Screening a commercial documentary about black culture was a first for the Los Angeles Music Center. Designed by the city’s civic elite, the institution aimed to make downtown more attractive to white-collar commuters, business developers, high-culture arts patrons, and middle-class Angelenos seeking a new leisure destination. The complex was one of Los Angeles’s most prestigious performance halls for European classical music, theatrical drama, and opera. While exhibition of the film in this venue distanced it from the vernacular culture the film represented as well as from the people of South Central, many in the black press viewed the documentary’s display as a point of pride. Wattstax’s subject and the guests’ flamboyant fashions transgressed the conservative norms of the then five-year-old venue. And the inclusiveness of the event differentiated the premiere from standard Hollywood openings. The 2,100 invited guests included popular entertainers, community leaders, and government officials. Attendees included black city councilman (and soon to be mayor) Tom Bradley, executive director of the United Negro College Fund Arthur Fletcher, founder of the Watts Summer Festival Tommy Jacquette, personnel from Stax and Wolper Productions, famous entertainers Jim Brown, Redd Foxx, Cicely Tyson, and Sonny and Cher, as well as mayor of Compton Douglas Dollarhide. In a cover story for Soul: America’s Most Soulful Newspaper, Leah Davis described the lavishness and showbiz quality of the event, chronicling how “searchlights scanned the heavens pointing to the direction in which a galaxy of new film stars was to be launched.” Isaac Hayes “arrived in fur in a white Rolls Royce with motorcycle escort” and “the Luxurious Ahmanson Theater was filled with beautiful people, beautifully garbed.”47 Congresswoman Yvonne Brathwaite-Burke began the evening by presenting a $3,000 scholarship to Crenshaw High School student filmmaker Stanley Houseton.

FIGURE 18: Advertisement for Wattstax, 1973, 35mm; directed by Mel Stuart; produced by Stax Records and Wolper Productions; distributed by Columbia Pictures. Author’s collection.

Localized screenings followed that connected the film to other cultural efforts. The documentary was shown at the Watts Writers Workshop in South Central in mid-February to an enthusiastic group. A memo about the exhibition noted, “The packed house laughed, cried, sang and shouted their approval of Wattstax the Living Word.”48 For its New York release, Wattstax opened at a benefit for the Harlem-based Schomburg Collection for Research in Black Culture. As part of a benefit for Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity), Reverend Jesse Jackson hosted the Midwest premiere at the Oriental Theatre in Chicago. For additional screenings in Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Sentinel ran an advertisement with a quote from Bob Johnson’s JET magazine article on the film: “Wattstax is rated ‘R’ by a Motion Picture jury, but in the black community, Wattstax is rated ‘MF.’*”49 The “MF” stood for “magnificent film.” Another gauge of the documentary’s positive reception was the encouraging letters sent to its producers. Crenshaw resident August Jones wrote in a letter to Wolper, “[It] is an enthralling, awe-inspiring experience to see and hear 100,000 folks, black folks, in a symphony of festive excitement and exhilarating pride.”50

FIGURE 19: Cover, Soul: America’s Most Soulful Newspaper, March 12, 1973. Author’s collection.

Some well-known reviewers claimed that Wattstax failed to relay the feeling of being at the show. Vincent Canby of the New York Times dismissed Wattstax as a “slick souvenir program rather than a motion-picture documentary on the order of Woodstock, a film that assumed the shape of the event recorded.”51 Dennis Hunt of the Los Angeles Times called Wattstax “fragmented” and “skittery” and accused it of not having “enough moments of interest and hilarity to offset the stretches of boredom that occur when an interviewee lapses into rhetoric or a singer lumbers through a number.”52 Yet most national news organs praised rather than faulted the film for the ways it differed from conventional rockumentaries. Joy Gould Boyum of the Wall Street Journal interpreted Wattstax as being about more than the music: “Wattstax emerges [as] a more revealing social document than was Woodstock. . . . Wattstax is, then, less about a concert than it is about black attitudes and values, with the performed music serving to establish motifs which are further orchestrated by images of the concert audience, by sequences shot in the streets, shops, and churches of Watts, and by a running commentary provided by black comedian Richard Pryor.”53 The Hollywood Reporter called Stax a “stand out” in “the age of mixed media” for uniquely combining diversification and community involvement.54 In the same publication, Ron Pennington wrote two months later, “The concert was just a jumping off place and ‘Wattstax’ is much more than just another rock concert documentary.”55 The Los Angeles publication Westways championed the choice to depart from the formulaic recording of a performance.56

The press continued to track Wattstax as it gained momentum and played overseas. In May 1973, Wattstax artists along with Bell, Shaw, Wolper, Stuart, and Pryor accompanied the film to the Cannes Film Festival. Although Wattstax technically played out of competition, its opening-night screening helped boost its prestige and advanced its path toward international exhibition. Shortly after Cannes, it played at the International Jazz Festival in Montreux, Switzerland, before starting a European tour. The showing of the documentary at the United Nations for fifty dignitaries from the Organization of African Unity, hosted by the famed Senegalese actor Johnny Sekka, contributed to Stax’s push to establish a greater presence in Nigeria, Algeria, Angola, Egypt, and Ethiopia.57

Targeting a cross-section of white viewers in the United States was motivated by both a desire for box office returns and the notion that fostering awareness of black culture would lead to increased interracial dialogue. “I hope [Wattstax] will be an easing of tensions,” Stuart told the Christian Science Monitor. He went on to mention that he hoped the film could “break down unnecessary fear. Help white people get over hang-ups about black people.”58 The strategies used to package the documentary for a crossover audience, however, resulted in a conflict between the subject matter of Wattstax and the way audiences were at times encouraged to view the film. Many advertisements downplayed the documentary’s engagement with black culture and the way it had been embraced by black moviegoers and critics, thus depoliticizing the film. An advertisement in the New York Times ran a quote from Bernard Drew of the Gannett News Service that praised the film in vague, generic terms, calling Wattstax “Funny, Funky, Tragic, and Triumphant.” An advertisement in the Wisconsin State Journal posted around campus at the University of Wisconsin ran the banner line, “You Can’t Judge a Movie by Its Color” and that “film critics everywhere,” including the Wall Street Journal, Saturday Review, and United Press International, hailed Wattstax as a motion picture that will be enjoyed “by all movie-goers.” Some advertisements went so far as to claim that Wattstax was intentionally created as an appealing object for white consumption. A Los Angeles Times advertisement for a multi-theater release in the city ran this line from a Newsweek article: “Wattstax is a welcome gift to white America!” The same quotation appeared in an announcement aimed at college students for UCLA’s UA Cinema Center screening in Westwood.59

The fact that Wattstax was not a runaway box office success was due in large part to its inability to penetrate the mainstream market. Perhaps the advertisements downplaying the film’s focus on black Los Angeles caused the counterculture to understand Wattstax as yet another concert film and thus ignore it. Or perhaps the subject matter of the documentary was seen as unappealing to white middle-class audiences who did not care to watch a film about black cultural expression and working-class Angelenos. Nonetheless, the film did generate a respectable amount of money and was well received both by critics and by black communities across the country.60 Importantly, those who labored on the documentary anticipated that it would directly lead to additional professional opportunities.

Bell’s vision of following Wattstax with a series of films and television programs encountered major problems. Stax chased existing genres and formats instead of playing to the strengths of the organization or tapping the depths of its creative resources; it overextended itself in motion pictures without a firm sense of direction. Stax first partnered with Paramount on the action drama The Klansman (1974). Despite the fact that the film was based on William Bradford Huie’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel and featured an all-star cast that included Lee Marvin, Richard Burton, and O.J. Simpson, the film was riddled with scandal during the production process and suffered numerous script alterations. In a New York Amsterdam News article, James P. Murray wrote:

In spite of all the trappings of a Hollywood blockbuster, “The Klansman” is bound to leave many serious film-goers miserable. The selection of such a book on such a topic would lead observers to expect a social consciousness film within an entertaining framework. Yet “The Klansman” represents none of this. . . . With three rapes, a castration, bloody shootouts and scene after scene of unreasoned racial invective, it rapidly becomes a pointless endeavor.61

Stax’s Darktown Strutters (1975) was also a disappointment. The film starred Trina Parks as leader of a female biker gang in Watts. Parks is searching for her mother, who has been abducted by a white fast-food magnate. As Parks discovers, the magnate is planning to kidnap and clone black leaders to keep the entire black population oppressed. Containing savvy criticisms of white racism through character parody and slapstick, Darktown Strutters was ultimately stranded between science fiction, action, and comedy. Genre conventions clashed and resulted in a pastiche of jokes, fight sequences, and brief moments of exposition. The black press wrote some complimentary articles about Parks, but the general consensus was that the film was scattered and full of tired conventions in a market oversaturated with blaxploitation.62

Stax expected that television would provide a fruitful route to film production in the mid-1970s, but the connection never materialized. Bell, Shaw, and Hamilton teamed up with Murray Schwartz of Merv Griffin Productions to tape a performance of Stax stars at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas in December 1972. The event was simultaneously broadcast on radio and taped for network television.63 Despite articles in the trade press asserting that the relationship with Merv Griffin was “a solid marriage,” the Vegas event did not lead to any further film or television programs.64

Stax’s financial troubles were amplified by a disastrous distribution deal with CBS Records that essentially routed Stax albums to regional commercial outlets rather than smaller stores. This prevented the label’s products from reaching their primary consumer base. Stax suffered from the industry-wide trend of conglomerates tightening their hold on the reach and creative freedom of independent companies. Charges brought against Bell for bank fraud, along with a controversy involving a payola scheme at the label, compounded Stax’s troubles. By 1975 the company filed for bankruptcy.65

Wattstax thus represented both a high point and the beginning of the end for Stax. Some of the other contributors to the film, however, went on to work successfully in motion pictures. Pryor moved full tilt into acting, appearing in Uptown Saturday Night (1974) and Silver Streak (1976). Cinematographer John Alonzo continued to work on New Hollywood productions such as Chinatown (1974). Roderick Young and Larry Clark charted a different path in the 1970s. Drawing on piecemeal funds from short-term commercial film jobs, as well the technological and intellectual resources of UCLA, they created independent films about struggles against class and racial inequality in South Central Los Angeles.

For Wolper Productions, Wattstax constituted the pivot project. Wolper would later write, “[Wattstax] marked the beginning of my relationship with the black community in film,” which in turn involved a new approach to developing projects.66 But going forward, Wolper Productions would not use Wattstax as a blueprint. In addition to the logistical challenges of such an endeavor, the resistance to Wattstax by mainstream viewers discouraged any such effort. Rather, the studio aimed to engage crossover audiences in prestige television as America’s two hundredth birthday approached. The studio’s docudramas would come to constitute an inventive liberal cultural form that addressed the increasing presence of minorities in the civic life of the nation, even as the vanguard liberation movements faced political repression over the course of the 1970s. Wolper Productions’ Roots (1977) would occupy the center of national debates concerning America’s bicentennial.