10

The Adoration of the Lamb

(paintings, 1432)

The Adoration of the Lamb, an altarpiece painted for the Cathedral of Saint Bavo in Ghent, is a towering landmark in the history of art. It was the first major masterpiece painted in oil, then a new medium for painting, and its achievement opened the floodgates for other painters to work with oil. This painting is also, in the opinion of many scholars, a fulcrum point in the transition between the style of the Middle Ages and that of Renaissance realism. No previous artist painted with such an eye for the smallest details or attempted to so painstakingly capture reality. It can be argued that Jan van Eyck’s The Adoration of the Lamb was both the last great medieval painting and the first great modern painting.

It is also a work with a fascinating history, so highly valued that it has been stolen numerous times during its existence—including being carted off to France as one of the spoils of war during the Napoleonic era, then taken again in the First World War. It was also a major target for Hitler’s acquisition in the Second World War, and it spent much of that war hidden away in an Austrian salt mine, waiting for the day when Hitler hoped to make it a central exhibit in his planned postwar art museum. It was only due to some heroic intervention that it was not destroyed during the final days of the war, and it is now again where it belongs—in the cathedral in Ghent.

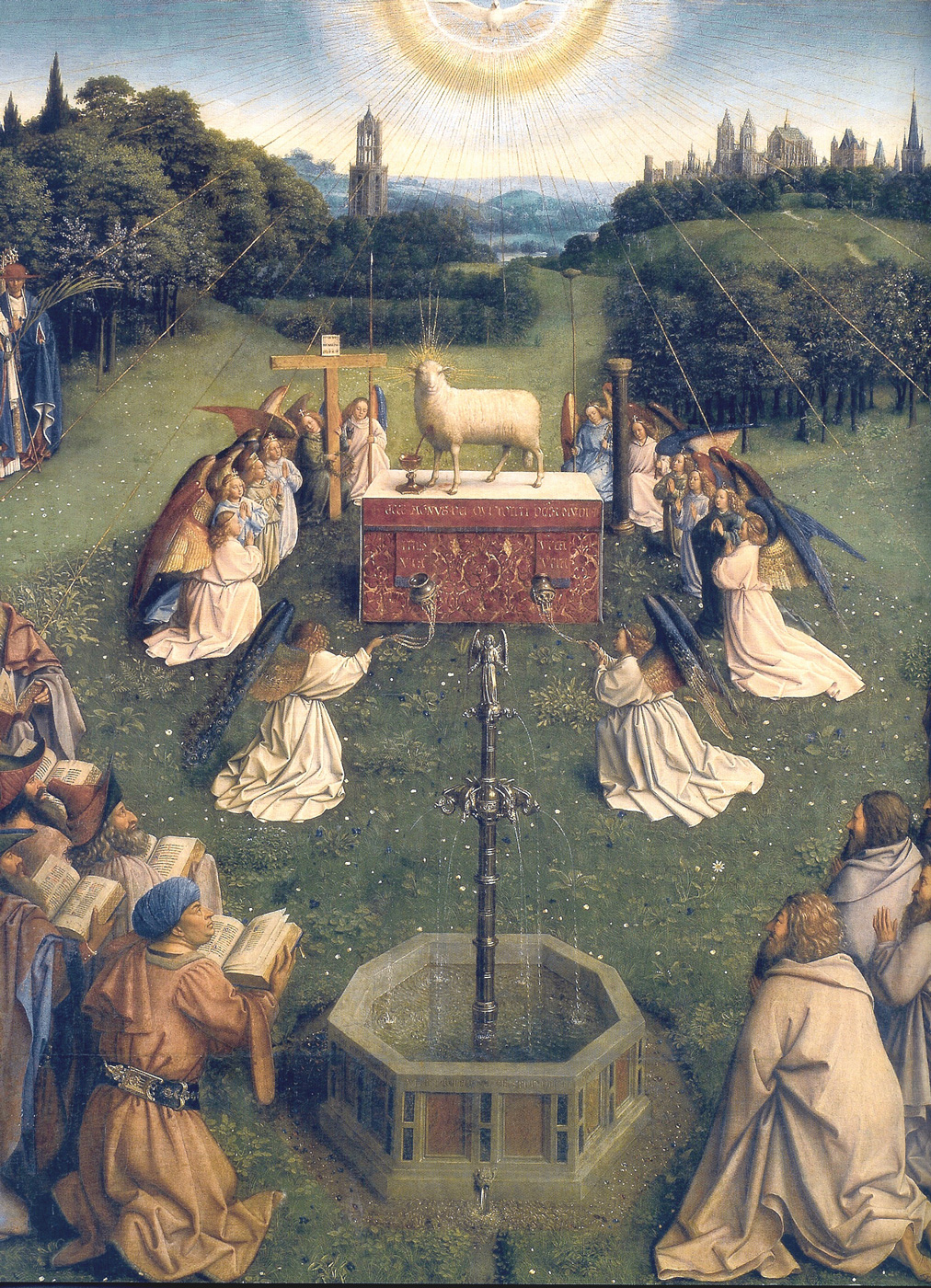

The Adoration of the Lamb (detail of the Ghent altarpiece) by Jan van Eyck, St. Bavo Cathedral, Ghent [Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD-Mark]

Begun in 1426 by Jan van Eyck’s brother Hubert, who died very shortly after work began, the huge altarpiece was not completed until 1432, and is probably almost entirely the work of Jan van Eyck himself. It consists of twenty linked panels: a large central set of images and two large wings that can close over it. These hinged wings are painted on both sides, so that the altarpiece may be viewed either open or closed. When it is opened, which is usually just for religious holidays, the work is a staggering twelve feet high and eighteen feet wide. The altarpiece is crowded with nearly two hundred figures. In the upper middle panel God the Father sits upon his throne, with a sparkling jeweled crown at his feet, painted with painstaking attention to detail. He is flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, angels who sing and play instruments, and Adam and Eve, who are painted with unflattering post-fall realism.

In the lower central panel we see the image evoked by the book of Revelation that gives the work its name. Christ, represented as a lamb, is in the middle of the painting, standing upon an altar with his sacrificial blood flowing from a wound into a golden chalice. The Holy Spirit descends as a dove. In front of the altar a fountain bursts forth with living water, and from every side pilgrims, hermits, religious and political leaders (the “just judges”), and angels converge upon the scene from the four corners of the earth to worship and adore the Lamb of God. Many of these figures are recognizable as historical saints, and others are contemporary figures from van Eyck’s day. They have all come to bask in the glory of the Lamb, whose altar is situated in a magical green field bedecked with flowers.

The trees and flowers are painted with such attention to detail that a modern botanist would be able to identify their species. In the distance we see a great city, the New Jerusalem, with its towers and cathedrals, and a lush realistic landscape stretching as far as we can see. Over it all, a heavenly light illuminates the scene. When its wings are closed, the altarpiece reveals an image of the annunciation, the prophets who predicted Jesus’s coming, and the figures of John the Baptist and John the apostle, painted with an effect of shadow and spotlighting that replicates the look of statues enclosed in niches.

The level of detail in the painting is without precedent in such a large-scale work. Only illuminated manuscripts had previously gloried in the kind of minute detail that can be seen in every single inch of this masterpiece. As art historian Noah Charney has written, “Viewers can make out tufts of grass, the wrinkles in an old worm-eaten apple, and warts on double chins. But they can also see the reflection of light caught in a perfectly painted ruby, the folds of a gilded garment, and individual silvery hairs amid the chestnut curls of a beard.”1 All these fine ephemera of the visible world are used to make a point about the reality of the invisible spiritual world, now here on display for the viewer. It embraces both this world and the next.

Jan van Eyck was born in what is now Belgium sometime before 1395. We don’t know a great deal about his life, but we do know he was a member of two princely courts in Holland. Van Eyck served as the court painter for John of Bavaria until 1425, after which time he joined the court of Philip the Good. Not only did he paint for Duke Philip but he also undertook diplomatic journeys for him, some involving extensive travel and “secret” missions. We don’t know the nature of these travels, but they may have helped him to develop the knowledge of landscape that is evidenced in many of his paintings.

We also don’t know with whom he studied the art of painting, but his own unique style is without precedent in the history of art. It used to be claimed that van Eyck was the inventor of oil painting, but scholars now believe it is more accurate to recognize him instead as the first artist to take full advantage of what oil painting could offer. Until the fifteenth century, the binding element for pigment was water and egg. But this egg tempera pigment created a flat and fairly uniform color. When oil was discovered as a binding agent, it opened up all kinds of possibilities for artists in terms of subtleties of color, luminosity, and tone. In particular, it allowed artists like van Eyck to render the effects of light with a new shimmering force.

The depth of the symbolism in the Ghent altarpiece would suggest that van Eyck had a strong familiarity with the Scriptures and theology, though it is also possible (as was often the case in paintings of this era) that he was guided in the symbolism by a theologian who helped map out the elements to be included in the work. Whatever the case, there is a profound understanding of the atoning work of Christ evident in this painting. When Albrecht Dürer saw the altarpiece in 1521, he praised it in his diary as a “very splendid, deeply reasoned painting.”2

The Ghent altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, St. Bavo Cathedral, Ghent [© Pol Mayer/Paul M. R. Maeyaert/ Wikimedia Commons, CC-by-SA-3.0]

The Ghent altarpiece is van Eyck’s oldest surviving work, and in the decade that followed it he also painted numerous portraits for private patrons. Only twenty-five paintings now exist that can be definitively attributed to van Eyck, among them the renowned Arnolfini Wedding Portrait (1434), a painting filled with finely painted details and rich symbolism. During the last decade of his life he also produced such works as A Man in a Red Turban (a 1433 self-portrait), The Madonna with Chancellor Rolin (c. 1435), and Madonna in a Church (c. 1438), where Mary is enormously tall in relation to the church interior, probably because van Eyck was using Mary as a metaphor for the church.

In each and every one of Jan van Eyck’s paintings, the details of architecture, of the natural world, and of the human face are painstakingly rendered and entirely convincing. Again and again, throughout his career, he succeeded in capturing the fine details and minutiae of this world, and he used them to remind us of the reality of the world to come and the Lamb of God who reigns over all.