39

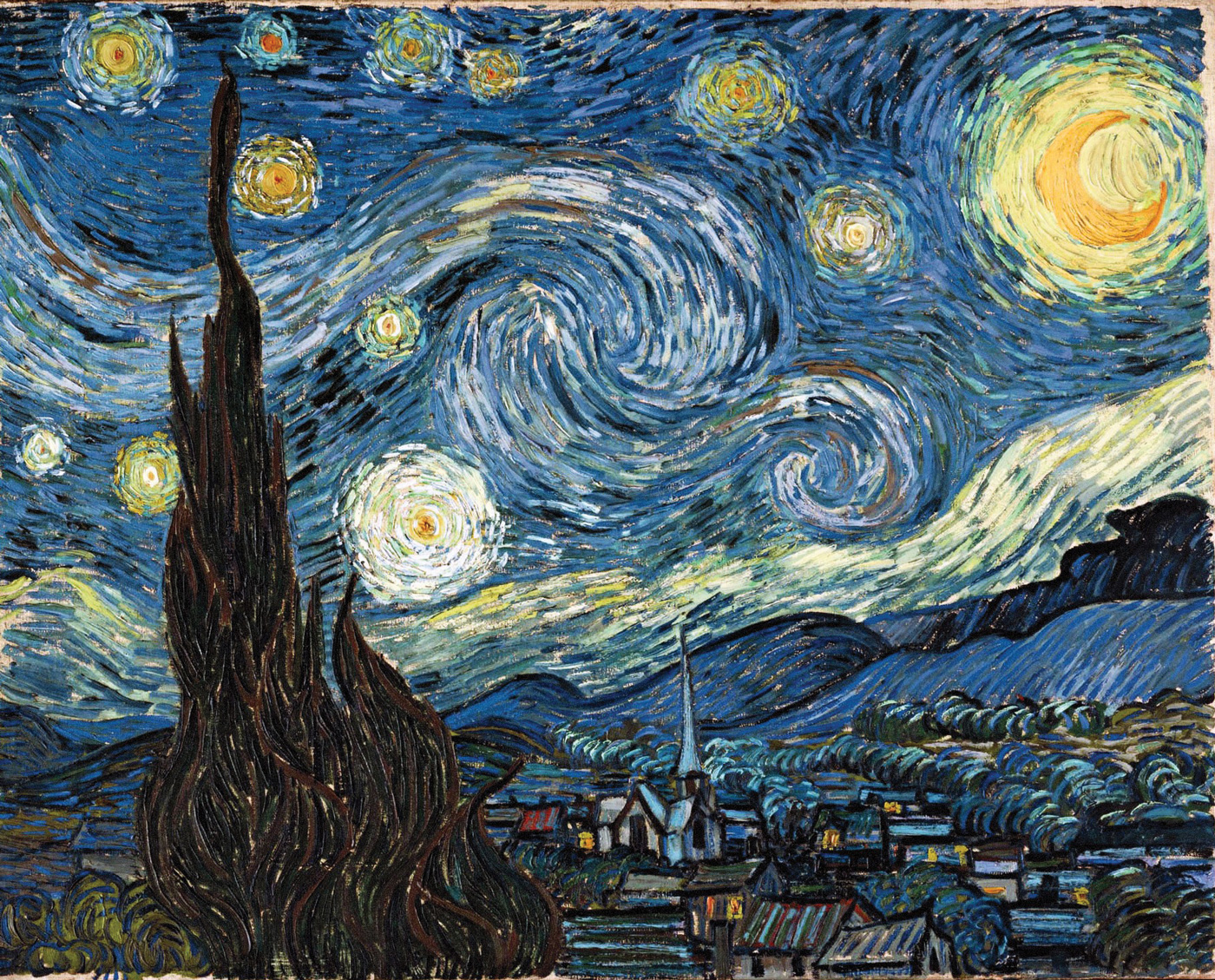

Starry Night

(painting, 1889)

Starry Night is one of those paintings so iconic—we’ve all seen it reproduced so many times—that it is difficult to really see. We have to step back and take a careful second look for it to begin to divulge all its wonder. This image of a small town seen from a vantage point on a hill is not so much concerned with the town as it is with the night sky overhead—a night sky that swirls and swells and spins above us. The painting itself feels strangely alive, as though it were itself an object in motion. The moon and the stars shine and shimmer in the midst of this pulsating vision of the sky, and one cannot help but wonder if, as he contemplated this scene, Vincent van Gogh experienced some sort of mystical vision of the eternal realities behind the earthly beauty. For van Gogh, a believing man deeply frustrated with religious institutions, it was in such visions that he discovered his connection with God. As he once wrote, “When I have a terrible need of—shall I say the word—religion, then I go out and paint the stars.”1 And that is precisely what he has done in this modern masterpiece.

The viewpoint in the painting from which the landscape is seen was the view from van Gogh’s bedroom window. He painted no less than twenty-one canvases of this particular landscape, though Starry Night is the most evocative of them all. The village seen in the painting is his invention, not something he could actually see from his window but rather added to the composition. When van Gogh sent several paintings to his brother so that he could try to sell them, he initially didn’t send Starry Night, evidently considering it less marketable than his others. In fact, he considered it a failure. Time, of course, has proven him wrong, as it has become one of his most popular works.

Some critics have wondered if the vision that produced Starry Night might have been something like a hallucination, with its violently expressive character and its paint applied in thick, churning, agitated strokes. But perhaps a better way to interpret the painting is to see it as the fruit of a dynamic spiritual vision, a moment when van Gogh, and by extension the viewer, felt almost absorbed into the swirling cosmos. It is as though we stand at the very threshold of the place where the temporal and eternal join together in a great swirling dance. Though the only traditional religious element in the painting is the inclusion of a chapel (with its light extinguished!), this is an unquestionably spiritual painting.

Vincent van Gogh was born in 1853 in the Netherlands, the eldest son of a Protestant pastor. Both his father and grandfather served as pastors in the Dutch Reformed church. As a child he was quiet, reflective, and a great lover of nature. At age sixteen he was apprenticed to the Hague branch of the art dealers Goupil and Co., where one of his uncles was a partner. This experience helped him to grow in his love and appreciation for fine art, though he did little more than the occasional sketch himself.

From 1873 to 1876 he worked in London and Paris, where two important things happened. First, he gained an ever-widening exposure to art through the museums in these cities. Second, he experienced a personal spiritual awakening. Beginning in September 1875, his letters were filled with quotations from the Bible and other spiritual writings he was voraciously digesting. (Much of what we know about van Gogh’s life and thought comes from the voluminous correspondence he kept up with his brother Theo, who as well as being a sounding board for his thoughts was also a constant financial support and encourager.)

As a young man van Gogh had embraced his father’s brand of liberal Protestantism, but now he became more evangelical in his approach, with a concern for the authority of the Bible, the preaching of the gospel, and personal salvation. His key influences other than the Bible were The Pilgrim’s Progress, On the Imitation of Christ, and the writings of famous London preacher Charles Spurgeon. Vincent offered his time to assist the pastor of the congregation he attended, and preached his first sermon in November 1876. About the experience, he wrote, “I felt like someone who has risen from a dark vault underground into the kind light of day when I stood at the pulpit, and it is a glorious thought that from now on wherever I go, I shall preach the gospel.”2

Van Gogh undertook a training program for missionaries and was assigned a temporary position with an organization that sent him to preach to the coal miners in the Borinage area of Belgium. There his goal was, as he told an acquaintance, to be “a friend to the poor like Jesus was.”3 He took this calling very seriously, living in the same squalid conditions as the poorest of the miners rather than in more comfortable lodgings as most missionaries of the time tended to do. He gave away his money and clothes, refused the lodgings of a more prosperous mining family, and instead slept in a bare hovel. He even refused the luxury of soap, and tended to be disheveled, soot-faced, and emaciated.

Starry Night, Vincent van Gogh, Museum of Modern Art, New York City [Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD-Mark]

Fiercely embracing the asceticism of The Imitation of Christ, he denied himself physical pleasures and even the simplest comforts. He wanted to model his life on the suffering servanthood of Jesus, and like John Bunyan he saw life as an arduous pilgrimage to a heavenly home. He preached and visited the sick, and was much loved by the miners for his gentleness, love, humility, and compassion. Taking the Sermon on the Mount literally, he used it as a model for his lifestyle. “Oh that I may be shown the way to devote my life more fully to the service of God and the Gospel,” he wrote. “I keep praying for it and in all humility I think I shall be heard.”4 He was, by all accounts, not a talented preacher, but he converted many of the hardened coal miners—less by his words than by his sacrificial love and care for them.

When his six months were up, the organization that had given him the appointment decided not to renew it, citing his lack of eloquence in the pulpit. But the more likely cause of his dismissal was the radical way he chose to live out his faith. “They think I am a madman because I wanted to be a true Christian,”5 he wrote to Theo. He tried to stay on through the rest of the year, doing without any regular financial means of support, until abject poverty and a growing disillusionment with the church caused him to abandon this ministry. His father also withdrew his support for his son’s pastoral ambitions, and even sought to have him placed in an asylum for his “excessive behavior.”

All this conspired to cause van Gogh to turn his back permanently on institutional religion. He never again set foot in church. Some biographers suggest that he abandoned his faith, but it seems clear, upon more careful reflection, that instead of abandoning it he simply rechanneled his spiritual passion into his art. His break with the church was not over theology but due to deeply personal disappointment, anger, and hurt. He quoted approvingly the dictum, “religions pass, but God remains.” He left the institution behind but continued a personal pursuit of God. “That God of the clergymen, He is for me as dead as a doornail. But am I an atheist for all that? . . . To believe in God for me is to feel that there is a God, not a dead one, or a stuffed one, but a living one.”6

As his ministerial dreams were collapsing, van Gogh was beginning to take his interest in drawing more seriously and began to produce a prodigious number of sketches, drawings, and then paintings. Much of his early work is focused on recording the squalid life of the underprivileged, while at the same time showing their dignity. This can be seen in such works as At Eternity’s Gate (1882) and The Potato Eaters (1885). Paintings such as A Pair of Shoes (1885) reveal his belief in the luminous holiness of simple ordinary objects. A painting he did of an open Bible next to a paperback novel by Zola seems to suggest that the Bible (open to Isaiah 53) and the Zola novel are both preaching the same message about suffering and the call to serve humanity. Throughout his life van Gogh lived out his own personal interpretation of the “suffering servant” passage of Scripture. He saw himself as a wounded healer who could use his own sufferings to bring new hope to others.

In 1886 van Gogh moved to Paris, where he met other important artists of the time and began to develop his own unique style of brushwork and his emphasis on vivid colors. It was a style that was vigorous, passionate, spontaneous, and instinctive. The paintings were highly textured, mirroring the plowing and the weaving of the peasants he so admired. A couple years later he moved to southeast France and made an aborted attempt to found a new working community of artists with Gauguin. But by this time he had begun to suffer from fainting spells and seizures, and the contrast of temperaments between the two artists soon led to a falling out, culminating in the infamous incident during which van Gogh cut off a piece of his own ear.

Van Gogh was hospitalized and then checked himself into an asylum in Saint-Remy. There are numerous theories about what caused his rapid deterioration and frequent bouts of near-insanity—schizophrenia, epilepsy, syphilis, or some combination of these. We shall likely never know, but in the last years of his life he was haunted by recurrent attacks. He would work intermittently when he could free himself from these bouts of intense sadness and despair, and he became afraid that he might eventually completely lose touch with reality. It was his art, essentially, that kept him sane, and his output during his stay at the asylum was unbelievably prodigious. In the last seventy days of his life he produced seventy paintings. Among his later works there is even a series of three paintings of biblical stories, showing that his interest in such matters had not waned despite the struggles of his life.

The popular image of van Gogh as a creative madman is one of the myths that keep us from properly understanding his work. His battle against his physical and psychological problems—and we’ll probably never know exactly what they were—did not enhance his art but more often kept him from working for periods at a time. His paintings were not the fruit of “madness.” It was when he was feeling well that he produced paintings of such incredible beauty and powerful original vision.

Another of the elements of the van Gogh myth has to do with the way he died. For years the popular conception was that he committed suicide because of his despair of ever being cured and his suffering from severe loneliness. But biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith have recently called that interpretation into question. Their reconstruction of the events and forensic evidence argues persuasively that van Gogh was more likely the victim of an accidental shooting than a suicide. The nature of the wounds and evidence of van Gogh’s upbeat frame of mind in the days before the shooting render the suicide hypothesis suspect. So we should be careful about reading his late paintings in light of theories about how he died. One of van Gogh’s last paintings, Wheatfield With Crows (1890), is often seen as a dark painting with a sense of suicidal despair and foreboding, but it can alternatively be understood as a hopeful vision. The crows taking flight might be an emblem of the eventual human triumph over death and the ultimate promise of eternity.

Vincent van Gogh was never content with just painting what he saw. He painted the sacred presence of the eternal as he saw it in our world. “If one feels the need of something grand, something infinite, something that makes one feel aware of God, one need not go far to find it,”7 he wrote. For van Gogh, all the simplest beauties that he loved so much were pointers that aimed the heart toward God: “I always think that the best way to know God is to love many things.”8