40

The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ

(paintings, 1896)

Though extremely popular in his day, in our time James Tissot has been largely relegated to a footnote in nineteenth-century art history. But when his carefully researched collection of 350 watercolors depicting the life of Jesus was first published as a book in 1896, it found a large and enthusiastic audience. No one who had followed his previous career could have anticipated that this painter of urban life in Paris and London would undertake the project of painting virtually every event in the Gospels.

The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ project took nearly ten years to complete. When it was done, it chronicled the entire life of Jesus as recorded in the New Testament in a series of 350 watercolors. To research the project Tissot traveled to Egypt, Syria, and Palestine in 1886–87, and again in 1890. While in the Holy Land he closely observed the landscape, the vegetation, the architecture, and the manner of dress, and filled sketchbooks with what he saw. He talked with rabbis and studied Talmudic literature as well as theological and historical volumes. He believed that there was still a remaining “aura” in the places where the Gospel events took place, and he spoke of having mystical experiences that added to his careful research. What he wanted to create was something as close as possible to an eyewitness account of the life of Jesus.

Once widely known as something of a playboy, Tissot lived an almost ascetic existence as he worked on the project—studying, sketching, and painting. There were even rumors at the time (unfounded) that he had become a monk. He described his effort as “not labor, but prayer.” The resulting images covered virtually every event in the Gospels, from the birth of Jesus to his teaching and preaching, his miracles and healings, his parables, and the events of the Passion Week, culminating in the crucifixion and resurrection. All were created with an attempt at “you are there” realism. Some of the events of the last week are horrific in their accurate and careful detail, such as the scourging of Christ. Others are innovative, especially the image of the crucifixion entitled What Our Lord Saw from the Cross, which presents that familiar event from an unfamiliar vantage point—how it looked from the perspective of the One who died there for humanity.

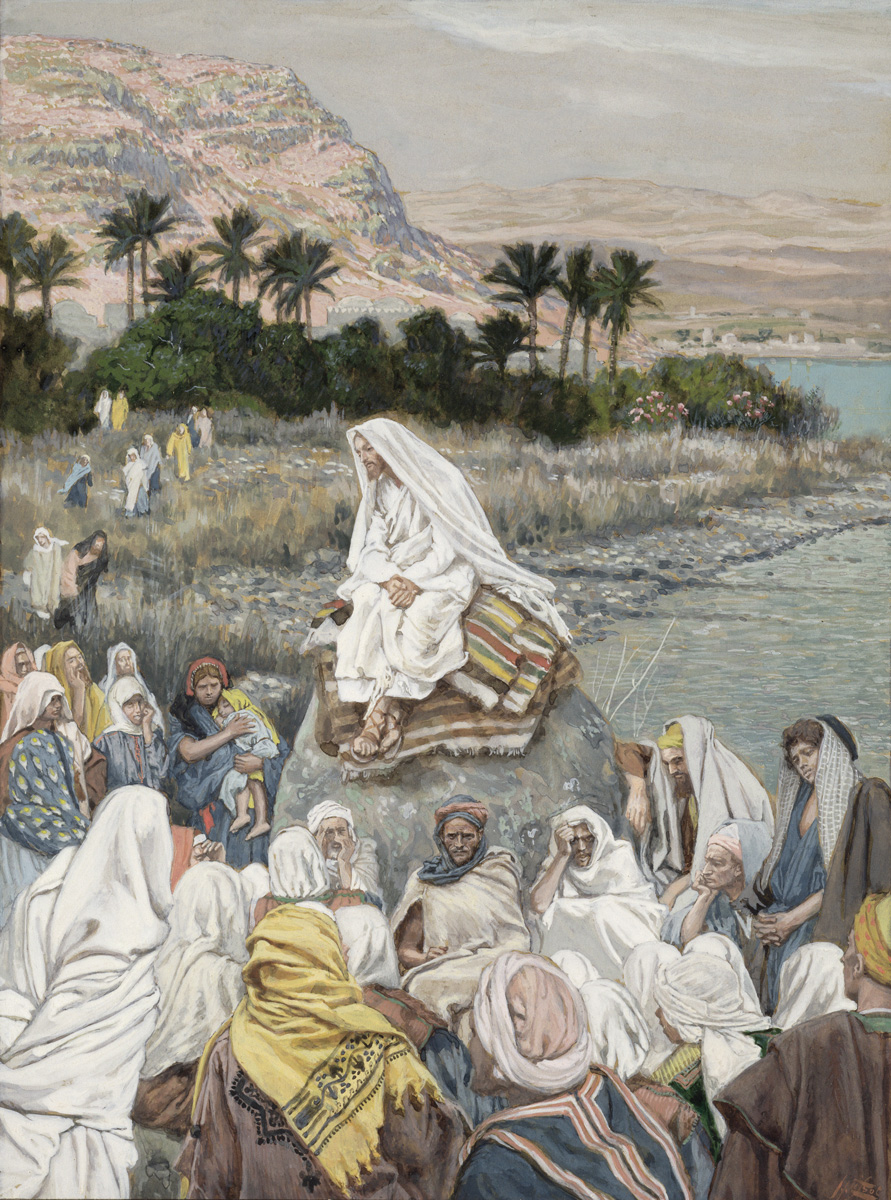

Jesus Sits by the Seashore and Preaches, from The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ by James Tissot, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York [Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA/Bridgeman Images]

In 1894 the finished paintings were exhibited to great acclaim in Paris, London, New York, Chicago, and other locations. They unfailingly drew large audiences, including many who were not normally accustomed to going to a museum or art gallery. These paintings had their critics—some saw their realism as cold and vulgar, not at all what one was used to seeing in religious works of art. But most embraced the works and found them deeply moving. There are even reports that the strong emotional responses from viewers included hushed reverence, weeping, and kneeling before the images. Tissot had indeed accomplished what he set out to do: give the viewer a powerful personal experience of the historical events that had changed the world.

These paintings proved to be so popular that they were issued as a multivolume set titled The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ that, in addition to the images, included a harmony of the Gospels, commentary by Tissot himself on the customs of biblical times, stories of his experiences while researching, and quotations from important historical and religious texts. Though an expensive set, it became an international bestseller. The final painting in the book is a self-portrait in which, surrounded by Catholic symbols, Tissot raises his hand in blessing. It is accompanied by a request that the reader pray for him.

James Tissot was born in France in 1836 to parents who were involved in the clothing industry. It is probably not surprising, then, that elaborate costumes and fashionable dresses were a common element of his early paintings. Brought up as a strict Catholic, he ceased attending church as an adult. Instead, he dedicated himself to a life of painting and the pursuit of pleasure. His paintings displayed his love for the finer things of life, for high society, and for beautiful women. A contemporary gossip columnist described him as “a high liver of extraordinary proficiency!” He had a reputation as a flirtatious man, and his paintings were largely of society women dressed in their finery, painted with care for detail and a sense of romance. What they lacked in gravitas they made up for in sheer loveliness.

Tissot lived in the age of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, but he was not really a part of either movement, though he was good friends with Degas, Manet, and Whistler. He was invited to take part in the first Impressionist exhibition, but declined. Instead, he blazed his own path, working in a highly finished style and becoming known for his paintings of fashionable ladies, usually in urban settings. He had a keen sense for composition and the arrangement of figures in his work, and for use of space, especially in a painting like The Ball On Shipboard (c. 1874), with its carefully arranged groupings of revelers. He also painted a series of four important paintings that recast the story of the prodigal son in a convincing contemporary setting, but Tissot really made his reputation as a painter who recorded modern life. His works are actually a great source of information about what fashions were popular at that time. Such cosmopolitan art proved very popular, and he made a successful career with such paintings.

In 1871 Tissot moved to London, where he continued to build his growing reputation and found a ready audience for his work. Not only were these highly productive years but they also included his introduction to Kathleen Newton, who became his model and the great love of his life. By all accounts it was a deep and committed relationship. They did not marry, but she moved in with him about 1876. Kathleen was a woman of fragile health, though, and she died of consumption a mere six years later. Heartbroken, Tissot returned to Paris.

Setting to work on a new series of images that depicted Parisian women in a variety of settings, he researched locations for each of the paintings. One of the places he visited was the Church of Saint-Sulpice. Long a Catholic more by custom than conviction, he had a profound experience in the church that day. When the priest raised the host during mass, Tissot experienced a vision that changed his life and his artistic priorities. He was so affected that he went without sleep for several nights to record that vision in Inward Voices (The Ruins) (1885). This painting showed a bloodied but still luminous Jesus comforting two poor and tattered souls in the rubble of a crumbling building. Jesus displays his bloodstained hands to prove that he is with them in their suffering and that he has died as a sacrifice for their redemption. It is a work of deep compassion and hope, and a sign of what was to come in Tissot’s art.

The paintings in The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ series were the major undertaking of his life after his conversion experience, but they would not be the end of his interest in biblical subject matter. In the latter years of his life he began a series of Old Testament paintings and drawings but died before he could complete the project. These include ninety-five images from the book of Genesis as well as many other paintings of important Old Testament stories.

When Tissot surveyed the long history of biblical art, he was disturbed by the anachronisms of earlier artists, who seemed to care little for historical accuracy in their work. He wanted to create something new—a carefully researched and accurate picture of the events as they would have actually looked if one had been there to observe them. “For a long time,” he wrote, “the imagination of the Christian world has been led astray by the fancies of artists; there is a whole army of delusions to be overturned.”1 He wanted to present an authentically Jewish Jesus, strong and charismatic, one who was truly man as well as truly God, and his hope was that viewers would personally identify with the story of Jesus through looking at his paintings.

What Tissot tried to do in his paintings was make the biblical stories come alive while striving for an almost journalistic level of accuracy. The expansiveness of the project, and the piety and care with which it was executed, make it deserving of more attention than it has received in our time. Once a large draw to the Brooklyn Museum, which raised the money to buy the complete The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ series through enthusiastic public donations, the works are now rarely exhibited and are stored in their archives. But they remain one of the most unique treasures in the history of Christian art.