60

Au Hasard du Balthasar

(film, 1966)

When fabled film producer Dino de Laurentiis wanted to create a series of films based on the Bible, he approached Robert Bresson to direct the initial film on the book of Genesis. After all, Bresson was considered to be one of the greatest living directors and was also a man not afraid to be identified as a Christian. He seemed the perfect fit. But when Bresson, with his usual passion for communicating truth indirectly, said that he wanted to have the dialogue in Hebrew and Aramaic, and that he wouldn’t actually show any animals on Noah’s Ark, just their footprints, de Laurentiis realized that he had asked the wrong man to helm the rich spectacle that he had in mind. (This movie on Genesis was eventually made as The Bible: In the Beginning, with John Huston as director, but was not successful enough to justify further films in the series.)

As a Christian who was a filmmaker, Robert Bresson often dealt with spiritual themes and built his scripts around religious characters, but he did not envision his films as a way to promote his faith. Instead, he used his unique and austere cinematic style to give viewers a glimpse of the realities that lay just beneath the surface of everyday life. Those who have written studies of his work often refer to his style as “spiritual” or “transcendental,” as it tries to reveal something deeper than what the viewer initially perceives.

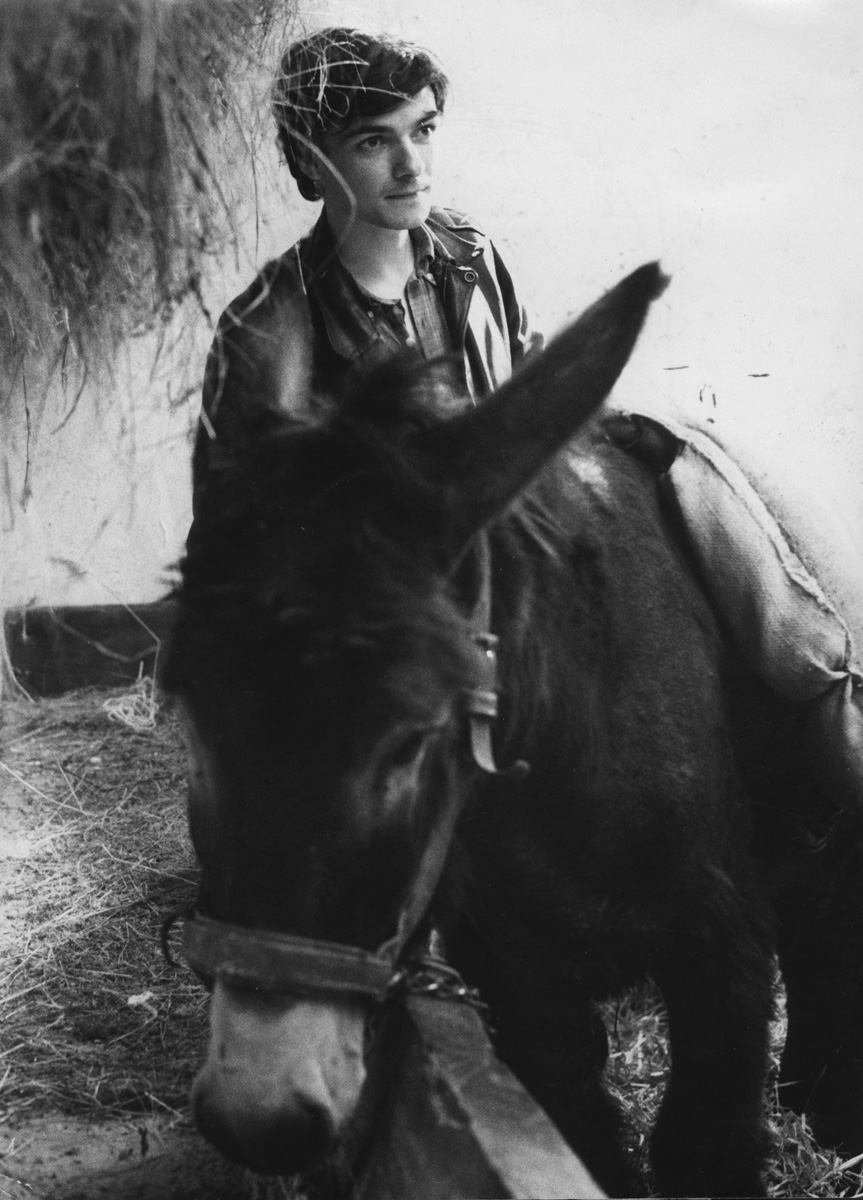

Still from Au Hasard du Balthasar [The Kobal Collection/Art Resource, New York]

With Au Hasard du Balthasar, Bresson investigates the spiritual impact on life through telling the story of a suffering and saintly donkey. He purposely chose a humble donkey as his lead character because of its resonance with biblical stories and because it was a beast of burden. Jean-Luc Godard once described this film as “the real world in an hour and a half,” and Bresson revealed it to be a world filled with pain, suffering, and injustice. Through the experiences of the gentle donkey we see the cruelty that humans inflict upon animals and upon each other in a heartbreaking story that reveals the depths of human sin while providing a few moments along the way where grace and redemption can be fleetingly glimpsed. Balthasar is a kind of Christ-figure, bearing the sins of man. He is innocent and holy. One woman in the film even speaks of him as “a saint.” And at the end of the film it is human selfishness and vice that cause his death. In the unforgettable closing moments, we see the wounded Balthasar stumble and fall in a mountain meadow, and as he brays out his pain he is surrounded by a flock of grazing sheep. We hear the gentle sound of the resonant bells around the necks of the sheep; a strangely moving moment that points to something mystical and sacred.

Robert Bresson was born in France in 1901 and was a painter and a fashion photographer before finally moving into a career in filmmaking. He always believed that films should be more like paintings than filmed theatrical productions. During his forty-year career, Bresson only produced thirteen films, and none of them were popular hits. But his body of work has been an inspiration and guide to countless modern directors who have taken elements of his aesthetic and made them their own.

Among Bresson’s thirteen films are several standouts. Diary of a Country Priest (1951) adapts the Bernanos novel about an unnamed priest struggling with doubts about God and about his own adequacy for the job, as well as facing outright nastiness from the citizens of his village. The priest becomes sick and dies while still at work trying to bring his parishioners to faith, but not before drawing the conclusion that makes up the final line of the film: “All is grace.” A Man Escaped (1956), probably his most accessible film, is the story of a member of the French resistance who manages to escape a Nazi prison by careful and meticulous planning and timely help from the providential intervention of God. Pickpocket (1959), reminiscent of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, is the tale of an amoral young man who learns the art of “lifting” wallets and purses. He finally shows signs of repentance and redemption in the closing scene that takes place in the cellblock where he is being held. Bresson’s later films of the ’60s and ’70s mostly lack the clarity and power of his earlier works (with the notable exception of Au Hasard du Balthasar), and give evidence of his growing dismay about the nihilism of modern life. “Things are going very badly,” he said. “People are becoming more materialist and cruel. . . . They are all interested in money only. Money is becoming their God. God doesn’t exist for many.”1

In creating his films, Bresson believed that form was more important than content. In other words, it was less about what his films said than how they said it. And he developed a unique philosophy for filmmaking that guided his productions, which he eventually explained in a small volume of aphorisms he published called Notes on the Cinematographer (1975). In this little book he distinguished his own work—cinematography—from cinema, the traditional way that films are made. He saw most films as being so focused on dramatic acting that they lost their deeper sense of reality and ultimately had less impact on the human soul. Bresson was committed to using a sense of life’s mysteriousness to create a place for self-discovery on the part of the viewer. “Hide the ideas,” he wrote, “but so that people find them. The most important will be the most hidden.”2 To accomplish this required great focus and economy of means on the part of the director, a rigorous and austere quest for purity of expression. “Everything should not be shown, or there is no art; art lies in suggestion. . . . Mystery should be preserved; since we live in mystery, mystery should be on the screen.”3 He proposes several ways to achieve this end.

First, Bresson was opposed to the normal acting style deployed in most films, a style in which actors used their voice and gestures to communicate the emotional state of the characters they play. Instead, Bresson strove for an emotionally flatter style of acting, where the actor speaks with more restraint, little intonation, and limited facial expression. The actor was coached by Bresson to deliver his or her lines more mechanically, almost in monotone, which Bresson felt would strip away emotional falseness. Basically, he wanted his actors, whom he distinguished from the norm by calling them “models,” to quit acting. When this occurred, Bresson believed, the interior life of the character became more evident, as it was not hidden under layers of performance. He was trying to get at something deeper in the portrayal of human beings, and so he quit using professional actors after his first two films, relying on amateurs whom he could train in his own unique acting style. This worked better in some of his films than in others, but when it worked at its best it could create a performance that felt strangely real and highly revelatory.

Second, Bresson placed great emphasis on the importance of the film’s soundtrack. The further he developed in his career, the less he employed the usual kind of background music that tipped viewers off as to how they were supposed to respond, or tried to amplify the emotional impact of a scene through musical cues. There is, of course, no wash of violins that pierce our ears when we feel deeply in real life, so Bresson didn’t want to express that kind of falseness in his films. Instead, he focused on placing the appropriate real sounds into the mix, and sometimes even revealed important actions by sounds offscreen so that the viewer hears rather than sees. “The noises,” he wrote, “must become the music.”4 Bresson was also not afraid of stretches of silence in his films, where there is quite literally no sound, something unthinkable in the normal methods of filmmaking. But he believed that silence sometimes best communicated the truths he was filming and created a space for the viewer to respond on his or her own terms.

Third, Bresson limited the movement of the camera to that which was absolutely necessary, and didn’t want fancy camera moves to draw attention to themselves. He restricted his use of pans and sweeping shots, instead building up his storytelling through the use of tightly composed scenes, in which he sometimes focused on hands and feet rather than on faces. His camera lingered upon the details. Bresson was fascinated by details, and was meticulous in presenting them—the sleight-of-hand methods of the thieves in Pickpocket, the step-by-step procedure by which a prison break was planned in A Man Escaped, or the rituals of the daily rounds of a priest in The Diary of a Country Priest. Bresson meticulously re-created the mundane repetitiveness of daily life, providing a tension-producing hint that there were deeper forces at work in the midst of that ordinariness, and then creating a moment when something extraordinary erupts from, and breaks through, the placidity. When that happens, the experience is revelatory.

Throughout his films, Robert Bresson was intent on revealing a supernatural order of being that existed behind and beneath the ordinary. As he said in an interview, “I’d like to make perceptible the soul and the superior presence that is omnipresent, this entity which is God.” But he didn’t want to do this through cinematic preaching or overly dramatic means. “I want to make people who see the films to feel the presence of God in ordinary life. . . . There is a presence of something which I call God, but I don’t want to show it too much. I prefer to make people feel it.”5 When his films work at their best, that is what happens—a divine presence makes itself felt in the lives of the struggling and the suffering, which produces a purifying glimpse of the salvation that is ever available.