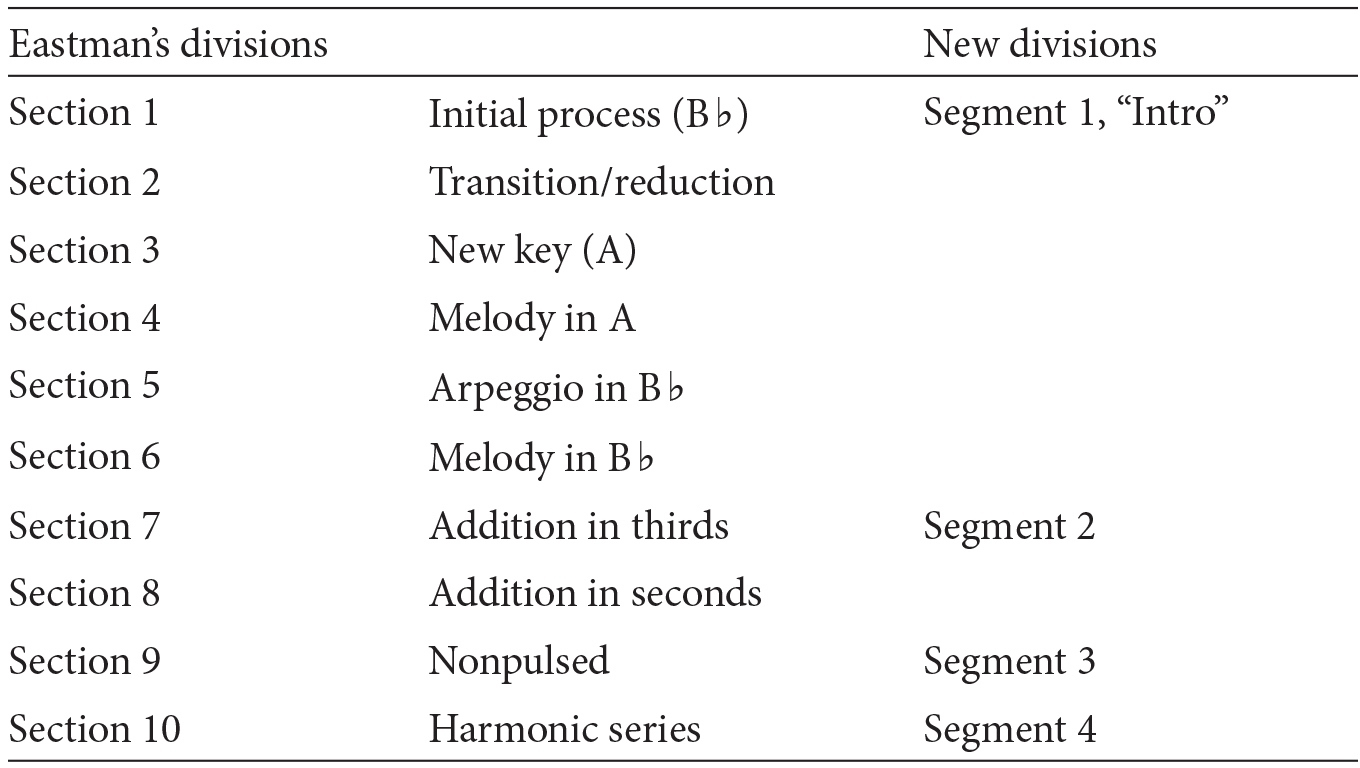

Table 9.1. Crazy Nigger organizational chart

No one can deny that Julius Eastman had a unique voice, both literally and compositionally. Figures such as Kyle Gann, Mary Jane Leach, and Diamanda Galas have all singled out Eastman’s music as being inimitable and unforgettable.1 However, until recently there has been little study of what distinguishes his voice. At first glance, an openly gay African-American composer, championed by the likes of Morton Feldman and Lukas Foss, would provide ample avenues to explore his work both analytically and hermeneutically. But his erratic career, the dispersion of his scores, and the cryptic nature of those scores that have been found, make the performance or even cursory knowledge of his works, much less intensive analysis, tremendously difficult. The work of Leach, Joseph Kubera, and Cees van Zeeland constitute a concentration of materials concerning Eastman’s late 1970s work Crazy Nigger.2 Several of the techniques Eastman used in this work are salient to the listener, such as his bracing dissonance and the obscuring of minimalism’s omnipresent pulse. Through analysis, the origins of these qualities reveal themselves to be extended tonalities more akin to Stravinsky and Bartók than the French symbolists, ragas, and modal jazz that informed earlier minimalists, as well as a larger overall additive process Eastman called “organic music.”

My analysis is based on three sources. The first is a facsimile of an autograph score from Mary Jane Leach’s online compilation of Eastman’s scores. The second is a live recording available on the New World Records CD set Unjust Malaise. This recording dates from a concert given at Northwestern University as part of his residency there in January 1980, which featured Eastman as one of four pianists performing Crazy Nigger, along with two identically scored works: Evil Nigger and Gay Guerrilla. Like many contemporary minimalist composers, Eastman’s scores were never intended for transmission as much as they were mnemonic reminders for his own performances. Thus, either a recording or the memories of performers are vital for the resolution from the score into sounding music. The third source is a schematic in Eastman’s hand from a February 1980 performance at The Kitchen in New York City. Classification of this document lies somewhere between a sketch and program notes. The schematic provides invaluable insight into Eastman’s compositional process and the overarching form of the work, but this is a document intended for public consumption. It should be noted that the schematic is not an exhaustive diagram of Crazy Nigger’s processes, and thus further illustrates which processes Eastman chose to highlight to his audience.

Eastman’s schematic divides Crazy Nigger into ten sections, each demarcating a change in process.3 The entire work is based on a vertical additive process, in which new parts are added and removed as others continue, resulting in increasingly dense harmonies. Once each process has reached its “logical conclusion,” according to Eastman, it resets to a single repeated note resulting in a sawtooth motion of harmonic complexity.4

The work is scored for any number of instruments of the same family, so each part is notated on its own staff with stemless noteheads. Although the attacks by the different players are not necessarily aligned, the most obvious aural perception is that of a steadily evolving progression of chords. Eastman suggests this in the schematic by referring to figuration and other motion in the individual parts as appoggiaturas.

I have divided Crazy Nigger into four larger segments, also by process, but on a more general level than Eastman. A chart comparing my divisions to Eastman’s is shown as table 9.1. The first segment comprises sections 1–6, each of which builds toward a particular mode or chord. The second segment encompasses sections 7 and 8, which construct even larger chords by thirds and seconds, respectively. Sections 9 and 10 use idiosyncratic processes and will be discussed individually.

The term “key” appears five times on the first page of the schematic. Eastman seems to have considered Crazy Nigger to be tonal, although obviously not in a functional sense. The tonal center is established at the beginning of each additive phrase, by a single repeating note. Examining only the first three additive phrases, the first and third have a tonal center Bb, whereas the second occurs on a tonal center of A. Of these three, only the first concludes in a recognizable functional chord, a dominant ninth-flat five, whereas the other two more fully realize their modality through melodic and arpeggiated figures.

Eastman began all three of these additive processes with whole-tone movement, and each takes three measures before adding parts, which settle them into a particular mode. These figures include transitional phases between processes that Eastman discarded from the remainder of the work. In the first Bb area, this consists of a simplification of the previous chord’s figures. Eastman labels this single measure as section 2 (illustrated in ex. 9.1). Eastman removes C# and D§ appoggiaturas, and transforms the diminished fifth (E§) into an augmented fifth (F#).

The A tonal area ends after three minutes, in contrast to the first Bb area, which lasts ten and half, and does so with a descending melodic figure followed by ten seconds of silence. The second Bb area ends with this same melodic figure, enharmonically transposed to the key. This is the first example of a technique Eastman referred as “organic music.” In his introduction to the recorded recital at Northwestern, he describes “organic music” as:

The third part of any part, so the third measure or the third section, the third part, has to contain all of the information of the first two parts and then go on from there. So therefore, unlike Romantic music or Classical music, where you have different sections and you have these sections, for instance are in great contrast to the first section or to some other section in the piece, these pieces, they’re not exactly perfect, but there is an attempt to make every section contain all the information of the previous section, or else take out information at a gradual and logical rate.5

In this introductory segment, the three parts that Eastman refers to are the three tonal areas. From the first area, the third inherits its tonal center and its mixolydian mode, while from the second, it receives the melodic figure and the addition of ascending whole tones.

This first segment also includes the first hints in this work of Eastman expanding upon the minimalist aesthetic of nonfunctional tonality by incorporating bitonality. Although C§ lies within the key of B flat, in the final two measures of section 1, a C indicated in “long note + octaves” is added. In his schematic, Eastman explicitly states the purpose of this is to establish two keys, C and B flat.

In the second segment of the work, sections 7 and 8, we come to a new tonal area of F minor, and several changes are made to the additive process. Rather than establishing a tonal center with a single repeated note, section 7 begins with an F-minor triad. Starting with a much less ambiguous kernel than before, Eastman uses an additive process by ascending thirds similar to the first section. Instead of using whole tones as a tonally evasive maneuver, this process is firmly in F Dorian. Once all the notes in the mode are exhausted, the process begins to fill in ascending seconds.

Just as section 2 is a simplification and alteration of the process for section 1, Eastman treats section 8 similarly in relation to section 7. Instead of beginning with addition by thirds before resorting to seconds, Eastman begins the process with seconds, and descends rather than ascends. This section begins with a single B, which would have been the next added note according to section 7’s process had Eastman allowed it to continue.

The motion in seconds quickly eliminates any sense of B as a tonal center, as this process continues until all twelve pitch classes are sounding. Rather than progressing downward by means of a single interval, Eastman uses a pattern that is symmetrical around a C/Db axis, which is shown in example 9.2.

Section 9 is by far the longest and most complex of the entire work (see ex. 9.3). While each of the previous sections consists of either a part of or an entire additive phrase, this section has six complete additive phrases, each resulting in a different final chord. This point also coincides with a radical shift in the notation of the score.

Throughout the majority of the score, Eastman notated the parts with unmeasured repeated noteheads. In section 9, however, a new aspect of rhythmic complexity is introduced. Rather than sharing a pulse, each player is now free to choose between any of a specific set of pitches and multiples of the pulse. In addition, the suggested duration of each measure is reduced from ninety seconds down to fifteen. The first eleven measures (34:00–36:45) of section 9, encompassing the first two iterations of the additive process, are written as whole notes on a grand staff. After this, he simply notated the pitch classes by name. Both methods are accompanied by either a range or discrete set of permissible durations.

Example 9.3. Excerpt from section 9 of autograph score of Crazy Nigger. Reproduced by permission from the Estate of Julius Eastman.

A third notational system is used in the schematic. Eastman highlighted the additive process that forms the basis of Crazy Nigger by labeling each part individually, though he does not label every part within the schematic. The totality of each measure is the sum of all the component figures linked with carats, using plus signs to divide each measure. He described each figure on its first appearance and sometimes reasserts it in subsequent appearances.

The labeling system follows a logical, if opaque, method. Returning to the introductory segment, in the Bb tonal area, the parts are labeled A and given a subscript index based on order of appearance. When these parts are later simplified, a sub-subscript of 1 is added. The two parts added in the A tonal area are labeled differently, as BA and BA1. All subsequent parts return to the previous labeling system.

It is fortuitous that this change in labeling occurs in the same place that best exemplified Eastman’s ideal of organic music. With one exception, every measure in section 9 consisting of three or more notes, contains both A- and B-labeled figures. By intentionally using notes from both the Bb and A tonal area, section 9 is the largest example of Eastman’s organic music, and likely the inspiration for this labeling system.

This is not the only way that section 9 expands upon prior material. Within this section, there are six complete additive phrases. Each of these results in a chord that refers to a previous section and is illustrated in example 9.4. The first additive phrase results in a D-major pentatonic scale, recalling the Mixolydian mode of the introductory segment.

The next three phrases of section 9 all result in symmetrical cells revolving around an axis that rises in semitones. The first of the three is based around a G/Ab axis, the second is an incomplete cell around Ab, and the final cell centers on an Ab/A axis. These all look back to the symmetrical nature of section 8, the process built on descending seconds. The fifth process of section 9 builds a chord that is similar to, although not exactly, the “transitional chord” from the introductory segment. The final process of this section is truncated one note shy of becoming an octatonic scale, OCT(0,1)B, specifically.

The final note to complete this octatonic scale would be a C#, which is the note that inaugurates the final section of this piece. Beginning with the C# below the bass staff (C#2),6 the added parts climb up the harmonic series to the E above the treble staff (E6) as the time between entrances shrinks from thirty seconds to only one. In this section, Eastman continues the rhythmic notation of section 9, beginning with forty pulses for the low C#, and increases the temporal frequency of each part by the same ratio as its pitch frequency.

The use of the harmonic series within minimalist works was already well-established by La Monte Young a decade before Crazy Nigger. But the direct mathematical correlation with temporal and pitch frequency is most associated with Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, particularly his 1977 work Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten.7 However, it seems unlikely that Eastman was aware of Pärt’s work, because the 1984 ECM New Series recordings, which brought Pärt fame in North America, had yet to be made.8

Eastman’s choice to base the harmonic series in section 10 on a C# makes sense (see ex. 9.5); he has already used one transition, where the next step in one process is then used as the first note of the next one. However, the appearance of C# is also meant to be dramatic, given that he took great pains to avoid using the pitch class anywhere else in the piece.

There are three instances in Crazy Nigger where the purposeful exclusion of this particular pitch class is obvious. First, of the three tonal areas used in the first half of the work, only A Mixolydian by definition includes a C#. While in this tonal area, all the notes of the mode are used except for C#. Second, in section 7 where the process is based on thirds and then seconds, Eastman resets the process when it reaches a B. If it had been allowed to proceed an additional step, it would have resulted in a C#. Finally, if all the labeled parts from the schematic are assembled as a list as in example 9.4, C# is notably absent.

One conclusion that could be drawn from the last example is that it was not given a label in the schematic because it did not appear in any part. However, this is not the case. In section 8, when the process is built on descending seconds, one of the parts is a repeating Db. This evades the schematic, as Eastman describes that section only by its process, rather than an explicit list of parts.

Of course, a Db is not the same thing as a C#. At 9:00, the last measure of section 1, however, a seventh and lowest part added remains mysteriously absent from the schematic. This part doubles the low C that was added in the previous measure, and also adds a C# appoggiatura. I believe the bookkeeping that obscures them is greater proof that the scarcity, if not absence, of C#s is a deliberate architectural decision.

Example 9.5. Penultimate page of Crazy Nigger. Reproduced by permission from the Estate of Julius Eastman.

By the late 1970s, when Crazy Nigger and the other pieces performed at Northwestern were written, the first wave of minimalist composers, such as Steve Reich and Philip Glass, had themselves moved away from strictly ideological compositional processes.9 So it would seem that the schematic represents the rigorous precompositional process, which would certainly be of great interest to an audience comprising composers and new music enthusiasts. On the other hand, the appearance of C#s before that pitch class’s “proper entry” indicates that Eastman did not conclude his composition with these processes, but felt free to make note-by-note changes for aesthetic reasons.

The use of extended tonality such as octatonic scales and symmetric cells in Crazy Nigger is another one of the ways that the minimalist aesthetic mutated into the postminimalist style. This particular innovation is often credited to European composers, particularly Louis Andriessen and his group Hoketus, who strove to make their own personal statements within a largely American conversation.

It may be even more dangerous to refer to this harmonic palette as “uptown” rather than European. Nevertheless, Eastman did spend time at academic institutions, such as the University at Buffalo and the Curtis Institute of Music, while maintaining a philosophy that embraced minimalism and managed to infuriate even John Cage. Therefore, Eastman’s work could be seen as an alternate history. While it seems unlikely that he intended to broker a détente between the two warring factions of Manhattan, it does appear that he was attempting to reconcile these two conflicted sides of his own compositional style.

Eastman’s harmonic language can also offer insight into his use of controversial titles. The reasons for and ramifications of Eastman’s titles are discussed to much greater effect elsewhere in this volume, but they do demand that even a highly analytical discussion of the work confronts the complications of race. In his introduction to the Northwestern concert, Eastman claims that his use of “work nigger” is meant to convey a sense of “basicness,” and “that thing which is fundamental.” This idea seems to run in opposition to the highly intellectualized and academic harmonic vocabulary he uses in the work. Conversely, if this work had been titled “Four Pianos” or “Music in Seventeen Parts,” that same academic language would make it profoundly easy to divorce it from its composer. Instead, the musicologist, the performer, and the listener must deal with Julius Eastman himself, or at least the conversations he wanted us to have. This is not a work for a committee to give an award to and then place onto a shelf.

So it seems that in this work Eastman has managed to suggest a different path minimalism may have taken—subvert the narrative of both African-American and academic composers, and make everyone profoundly uncomfortable in the process. Nonetheless, the music would not have survived the staggering odds against it, if it were not also engaging, searing, and unforgettable.

Notes

1.See Thomas Avena, “Interview: Diamanda Galás,” in Life Sentences: Writers, Artists, and AIDS (San Francisco: Mercury House, 1994), 178; Mary Jane Leach, “In Search of Julius Eastman,” NewMusicBox, November 8, 2005, http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/In-Search-of-Julius-Eastman/; Kyle Gann, “That Which Is Fundamental,” in Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 289.

2.In an annotated score by Cees Van Zeeland, he dates the work at 1978, which is written on the autograph score, but is cut off on the score posted online.

3.Julius Eastman, Crazy Nigger, schematic, accessed January 30, 2015, http://www.mjleach.com/EastmanScores.htm.

4.Julius Eastman, Crazy Nigger, facsimile score, accessed August 18, 2009, http://www.mjleach.com/EastmanScores.htm.

5.Julius Eastman, spoken introduction to Northwestern concert, Unjust Malaise, New World Records CD 80638, 2005.

6.Using the scientific pitch notation system, where middle C is C4, and octave numbering goes from C to C.

7.Daniel J. McConnell “Ringing Changes in Schoenberg’s Klangfarbenmetapher: Music by Schoenberg, Arvo Pärt, and Brian Eno,” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Nashville, TN, November 7, 2008. Since this essay was written, it has come to the attention of the editors that Spectral CANON for Conlon Nancarrow by James Tenney, conceived in 1972 and realized for player piano in 1974, works precisely with canonic forms for both pitch and rhythm, whereas Eastman worked with this same process in the last section of Crazy Nigger in a more intuitive manner.

8.ECM, “ECM–History,” accessed August 18, 2009, http://www.ecmrecords.com/About_ECM/History/index.php.

9.Timothy A. Johnson, “Minimalism: Aesthetic, Style, or Technique?” Musical Quarterly 78, no. 4 (Winter 1994): 749.