INTRODUCTION

Students of eighteenth-century Ireland know Arthur Young’s famous diatribe against the linen industry in Ulster written after his celebrated tour in the late 1770s. It opens:

Change the scene, and view the North of Ireland; you there behold a whole province peopled by weavers; it is they who cultivate, or rather beggar the soil, as well as work the looms; agriculture is there in ruins; it is cut up by the root; extirpated; annihilated; the whole region is the disgrace of the kingdom; all the crops you see are contemptible; nothing but filth and weeds. No other part of Ireland can exhibit the soil in such a state of poverty and desolation.

The tone of this comment does not accord well with Young’s observations as he made his way through Ulster, and nowhere does he spell out the evidence for his criticisms. It may be that his recollections were coloured by comments that had been made to him by agricultural improvers during his visit. He might even have read this pamphlet dedicated to Richard Robinson, Lord Rokeby and Primate of All Ireland (Church of Ireland), one of his most influential informants, and published only a few years before his visit.

The writer of this pamphlet claims that his reasons for considering the subject sprang from a discussion about the causes of ‘the great emigration of the lower kind of people to America’. He traced them back to the fundamental economic and social problems brought about by the rapid spread of the domestic linen industry throughout the countryside. In contrast to Young, however, he has explained how and why farmer-weavers managed to ‘beggar the soil’. Their major problem was lack of capital to stock the smallholdings – for farms averaging ten acres belie any other appellation – buy their seed, and allow their crops to reach maturity before harvest. The writer describes the difficulties of new families in establishing their farms as well as maintaining production of cloth.

The author deals only with the earliest stage of the family cycle, however, pointing out how the nursing of children deprived a man of the help of his wife in the field and at the loom. To recover from these expensive years there was a strong temptation for a couple to use the labour of their children as soon as it became available. A girl could spin by the age of four while a boy could assist his father at the loom until he was strong enough to weave about the age of fourteen. Especially in their teens children proved a real asset to the fortunes of a family. Problems returned when they wished to marry. If the parents wished to retain their support they had to set up the couple on a patch of land cut out of their own holding. Subdivision among members of the families was the consequence so that farms continued to be fragmented. An alternative to exploiting one’s own family was to let land out to cottiers. In return for working for the farmer-weaver they might be allowed the use of a ‘dry cot-take’ for planting potatoes, or a ‘wet cot-take’ that would include sufficient grass for a cow.

In the long term such continuous, intense subdivision produced great population densities, especially in north Armagh where the finest linens were produced. The 1841 census records the population of the barony of Oneilland East in the north-east corner of the county, including the town of Lurgan (4,205 persons) as 23,391 people living on 20,890 acres, a density of 716 to the square mile. A thousand people to the square mile was considerably exceeded in several rural townlands.

THE PAMPHLET

(p. v) To His Grace Dr. Richard Robinson, Primate of All Ireland, &c.

My Lord,

A very principal gentleman of this county, in whose company I had the honour of spending a few hours (p. vi) some time since, asked me, what I thought might be the cause of the great emigration of the lower kind of people to America?

The question, I found upon reflection, involved matters of the utmost consequence to this Kingdom – agriculture and the linen trade; for which reason, I have bestowed some time and pains in considering it; and, if I have been able to discuss it with accuracy and precision, I trust it will be found not altogether unworthy of your Grace’s attention and patronage.

The many great and lasting improvements, planned and executed by your Grace, for the public good, (p. vii) while they fill us with wonder and gratitude, are a certain pledge of your receiving favourably any attempt to follow, though at the most humble distance, your Grace’s patriotic example.

I am, with the most profound respect, My Lord, Your Grace’s most devoted, most obedient, and most humble servant, A FARMER. Armagh September 1, 1773.

(p. 9) In this age of improvement of the arts and sciences, it will not I hope be thought presuming, or impertinent, in one who affects no higher character than that of a rational practical farmer, to point out (p. 10) to the public, a scheme of profitable agriculture, which, while it enriches the farmer, will diffuse plenty of all sorts of provisions, through this manufacturing country, at a much cheaper rate, than they can now be sold for, from the wretched pitiful crops that we see yearly produced, by the present barbarous method of tilling the ground.

My ideas, which I shall endeavour to prove to be founded on facts, will probably expose me to much censure; but relying wholly on the integrity of my heart, and conceiving it to be the duty of every honest man to contribute, as much as in his power, to the Public Good; I shall not scruple to lay down the following axioms:

First, That the present mode of letting small farms to weavers, is extremely injudicious and prejudicial to this kingdom; and next, that such farms are never cultivated, in that spirited masterly manner, as is necessary for procuring that plenty of the fruits of the earth, which the providence of God, in His great bounty and goodness to man, hath given it a capability of.

To illustrate what I have to say on that subject, I must beg leave to suppose a tract of one thousand (p. 11) square acres of land, inhabited by one hundred weaving families each supported, in some measure, by the produce of its little farm of ten acres. This supposition will, I believe, be allowed to be no unfair representation of the whole of this manfacturing country, with some very few exceptions; and if I can demonstrate, that these little farmers, from their inability, by reason of their poverty or ignorance, do not raise above one-fourth part of the provisions, which their land would produce under a spirited rational culture; one of the points which I endeavour to establish, will be allowed me, and the other must of necessity fall in with it.

Let us then observe the weaver seated in his little farm, what will be his management of it? He begins generally with a capital not exceeding four pounds, including his loom, and with his wife’s fortune, (seldom so much, but scarce ever more) he may possibly add a small cow, and some wretched furniture for his cabin. Unable to keep a team, or even a single galloway, he must with patience wait till his more (p. 12) wealthy neigh-bour hath finished his spring labour, and then, when his corn should be four or five inches above ground, he hires the farmer’s jaded team to scratch up the surface of four acres of his little farm for oats from a lay of three years when it has been perfectly exhausted by his predecessor. On this he sows twenty bushels of seed which by giving him three months credit for, the farmer hath supplied him with, at twenty-five shillings per boll of ten bushels, when the price for money is only twenty shillings. And if he hath been fortunate and diligent enough to scrape up from about his door a little dung, (well stored with dock and nettle seed) he must hire a horse to carry it out, and with two days of his own labour, to spread it in the lazy-bed way, and the help of another as poor as himself, and his wife to lay the sets, he plants four bushels of potatoes, which he is to pay for, in about a month, at the rate of eighteen-pence per bushel, the current price being then only thirteen-pence, or fourteen-pence. (But I have known them buy potatoes upon credit for two shillings per bushell, when I was selling some of a much superior kind at (p. 13) sixteen pence.) The drawing out his dung, as well as the help he hath had in setting his potatoes, together with the ploughing and harrowing of his little spot under culture, must all be paid by his own labour; for the farmer, to avoid disbursing any money, makes it a condition to be paid for the use of his horses, by the weaver’s help, in setting and weeding his potatoes, and digging them out, and assisting in making his hay, turf, &c. to the unspeakable loss of the linen trade.

He hath found too in his farm, a rood of potato ground; this he gets laboured on the same terms as for his oats, and sows it with two pecks of flax seed, which some conscionable retailer of that commodity hath generously granted him a few months credit for, at the moderate advance of one or two shillings per week, above the ready money price; and if the credit given is for a longer time, the price rises beyond all (p. 14) degrees of proportion, so as to amount frequently to the double of what it sold for in the sowing season. His little spring labour being thus slovened over, his wife can then and not before, sit down to her wheel, and he to his loom, for five or six weeks, after which it will require the full exertion of their joint labours, to keep his little farm tolerably clean from weeds, and repay the engagements which he is under for tilling it. Five acres remain under grass, if such it may be called, which hath been perfectly exhausted by his predecessor; however such as it is, he contrives, with it and the assistance of the high road, to keep his little beast from starving the first year: he hath besides about half an acre of flat, wet, spritty ground, which he calls meadow. About the middle or latter end of July, impelled by hunger and want of credit, he begins to dig up his potatoes though not half arrived at maturity, so that by the end of November, they are above two-thirds consumed. If the linen trade hath been favourable to him, (that is if a number of (p. 15) commissioners, who lay out other folk’s money, or ignorant foolish young men, who are vain of shewing what large quantities they buy, have been busy in the markets) our little motley man, half weaver, and half farmer, hath contrived not to run in debt above two or three pounds.

His oats of four acres with the wretched culture they have had, do not produce more than one hundred bushels, which, if he hath not been forced to sell on the spot to pay his debts and rent, must now be disposed of, at the best price he can (at that cheap season) get for it, seldom exceeding thirteen-pence per bushel: he then sits down to his loom and his wife, as much as her state of pregnancy or nursing, will permit, to her wheel, and if the linen trade hath still continued favourable to him, that is, if he hath got for his web more than every true friend of this country should wish it to be sold for, who opens his eyes to future events and sees that the many powerful rivals we have in that branch, should induce, us, by every honest means, to undersell them; if this, I say, hath been the case, he may, perhaps, notwithstanding (p. 16) his loss in farming, have wrought himself clear of debt, by the time his spring labour comes round again.

This loss upon his farm, together with his expenses in housekeeping, for at least one-half of the year, must all be paid for out of the profits of his weaving; a melancholy reflection to the true friends of this unhappy infatuated country; especially when we consider, that the major part of the linen made here is coarse, and that the weaving farmer cannot by reason of his many avocations, work above fifteen double pieces in the year, consequently, there is an unnecessary load of near three shillings and six-pence laid on each piece, which is about one penny per yard, a trifle under.

(p. 17) (1) Dr. the Weaver’s Farm of 10 acres, at 14s. per acre rent & taxes

| £ | s. | d. | Cr. | £ | s. | d. | |

| To rent and taxes | 7 | 0 | 0 | By ten bolls of oats, @10s. 10d. | 5 | 8 | 4 |

| Ploughing for oats, four acres@ 5s. per ditto | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 stone of scutched flax @ 5½ d. per pound (great produce) | 1 | 18 | 6 |

| 20 Bushels oats, seed, @ 2s. 6d. | 2 | 10 | 0 | ½ acre of hay (high price) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sowing, harrowing @ 2s. 6d. | 0 | 10 | 0 | Grazing for hire, a small heifer | 0 | 10 | 6 |

| Drawing out dung for potatoes, and spreading | 0 | 3 | 10 | 35 bushels of potatoes, at 8d | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 men setting, a boy to lay | 0 | 2 | 1 | Straw | 1 | 17 | 0 |

| 4 bushels potato seed, @ 1s. 6d. | 0 | 6 | 0 | 11 | 17 | 8 | |

| Ploughing and sowing one rood for flax | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 2 Pecks, flax seed, @ 2s. 6d. | 0 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Weeding corn, flax and potatoes | 0 | 10 | 0 | ||||

| Reaping oats | 0 | 15 | 0 | Lost this year by the farm, (besides victualling women who attended the flax)* | 2 | 11 | 11 |

| Tythe of oats, @ 2s. meadow, and small dues 2/6 | 0 | 10 | 6 | 14 | 9 | 7 | |

| Pulling flax, 2 women 1 day | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Drowning, Lifting, spreading | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Drying with turf, beetling | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 6 Women scutching | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Digging potatoes | 0 | 2 | 8½ | ||||

| Cutting meadow, 6½ d., | 0 | 3 | 9½ | ||||

| winnowing hay 1s. 1d., bringing home, and stacking, 2s. 2d. | |||||||

| 14 | 9 | 7 |

(p. 18) His second year’s management is a transcript of the former, except that he takes from his pasture a rood of ground for potatoes, and sows with oats that which was nearly exhausted last year by his flax: this, while it diminishes his pasture, makes but a poor amends by tillage, as the oats after his flax do not yield above five bushels, and then he turns it out to rest for at least three years: His crop of four acres of oats, being the second from lay, is rather more favourable than the former, and he reaps one hundred and (p. 19) twenty bushels at the harvest. But as his family increases, the labour of his wife is consequently less, and though the linen trade hath still been brisk yet it requires his whole diligence and activity to wipe himself clear of debt by the following spring; for notwithstanding his crop of oats hath exceeded that of the former year twenty-five bushels yet the loss of the greater part of his wife’s labour, hath deprived him of all the advantage of it.

(p. 20) Dr. the Weaver’s Farm the second year

| £ | s. | d. | Cr. | £ | s. | d. | |

| To rent and charges as before | 14 | 9 | 7 | By produce as before | 11 | 17 | 8 |

| Ploughing and sowing with oats one rood of last year’s flax ground | 0 | 1 | 10½ | Additional produce more than last year on 4 acres of oats | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 5 Pecks of seed oats for it | 0 | 3 | 11 | 5 Bushels on a rood of flax | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Additional tythes | 6 | Additional straw more than last year, 37 stooks @ 3d | 0 | 9 | 3 | ||

| 14 | 15 | 1 | Lost this year by the farm | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 14 | 15 | 1 |

But the third year is the most distressful, for then, as his family increaseth in number, his crop decreaseth in quantity, as well as quality.

(p. 21) Dr. the Weaver’s Farm the third year

| £ | s. | d. | Cr. | £ | s. | d. | |

| To rent and charges as before | 14 | 15 | 1 | By 8 bolls of oats @ 9s. 9d. | 3 | 18 | 0 |

| Flax, hay & potatoes as before | 3 | 17 | 5½ | ||||

| By straw, 160 stooks @ 2d | 1 | 6 | 8 | ||||

| *Lost this year by the farm | 5 | 12 | 11½ | ||||

| 14 | 15 | 1 |

*Which upon 15 pieces of linen is a tax of 7s. 6d. each, above 2d. per yard.

(p. 22) His four acres, which are still in oats, produce no more than eighty bushels of a poor starved grain; and his wife’s inability, by her increase of family, to assist as before, obliges him to hire a boy, to attend his loom, and help to weed his crop, which from an injudicious course of slovenly tillage, requires it more than ever. More provisions must be had, and unable as he is to buy them, but from hand to mouth, he must in the spring, provide as he wants them, at an extravagant rate. Happy if the high price of linen enable him to stand his ground, indebted only four or five pounds. Every year afterwards, his circumstances grow worse and worse; so that to escape a jail, he makes a moon-light flitting, as it is called, and flies to England or America, or perhaps attaches himself to the service of some more wealthy neighbour, with whom he ever afterwards lives in a state of wretched dependence, of absolute beggary and vassalage. And here I appeal to most country gentlemen, whether they do not find many such about them; for my own part, I employ three of them in my little farm, and occasionally several of their children, (p. 23) who must otherwise have starved or gone a begging, and a great part of those whom I call in at hay and corn harvest, &c. consists of such. What then, will it be asked, shall we do with this very useful body of men to whose skill and labour we are indebted for our (only free) trade? I answer, if you wish the linen trade to flourish among us let them stick to their looms and, if they must have land, let them hold no more than is necessary for one or two cows’ grass. Throw your estates into farms from one to three hundred acres to be let to men who are able to cultivate them to the best advantage. Let these be discouraged under the most severe penalties, viz. double rents, from letting any part of them beyond a cotter’s take of three or four acres to one family, and oblige them also to pay an advanced rent for all their meadow and pasture beyond a certain proportion of their farm so as always to have at least two-thirds of it in labour. Let a judicious course of tillage be laid down for them and constrain them under heavy penalties to observe it. No more scratching the ground for three successive crops of oats and then (p. 24) leaving it, as they term it, to rest, as naked as the high road, five acres of which would scarcely keep a cow in flesh. Instead of that, substitute the following course or something similar, so as never to have two crops of white corn succeeding each other.

1 Potatoes with plough or dibble, to be cleaned with horse or hand-hoe

2 Bere or barley

3 Clover one year for meadow

5 Peas or beans, well-hoed

6 Oats

7 Turnips, well-hoed, and a slight dressing for

8 Wheat or barley

9 Flax, and then potatoes as before.

With such a course the farmer would take treble crops from the ground and would consequently be enabled to sell provisions at a much cheaper rate than he can now raise them for. The weaver having no avocation from his loom, could give up his whole time and attention to it and make at least eight or ten (p. 25) pieces more in the year, and of better cloth, than he can do now; and by the low price of provisions he could afford to sell his linens at such a rate as to command a constant foreign demand for them. Whereas (I shudder at the thought) if things are suffered to go on in the same course in which they have moved for some time past, we shall be undersold in all foreign markets; and when once the Dutch, French, German, and Russian linens have obtained some time, we shall find it next to impossible to get sale for ours. Let us not flatter ourselves. Our good friends the English and Americans will never think themselves obliged to take our goods if they are dearer or of an inferior quality to what they can import from other manufacturing countries. All that they owe us and indeed all that we have a right to expect from them, is to give us the preference of their money, the price and quality of our goods considered. I have now in my possession some remnants of hempen and flaxen Russian linens which I bought in London, at the third hand from the importer, where no doubt every man had his profit, (and which, moreover, had paid a heavy duty) which (p. 26) are cheaper and better than any I can procure in this manufacturing country. And yet it is a favourite maxim with many of our country gentlemen, that our brown linens can never be too high, not once reflecting upon the number of our competitors ready to undersell us nor that a trade where the profits between buyer and seller are not reciprocal must be of short duration. About thirty months since, when upon some expected demand for the American markets (in which however we were sadly disappointed)our brown linens rose to an extravagant price, I have known many gentlemen overjoyed at it, not considering that so unnatural a rise in the staple trade of a manufacturing country must in the nature of things soon subside and that lands then taken at the extreme high rents which the unthinking weaver then foolishly imagined the profit of his web would enable him to pay, must consequently sink as much below their real value whenever such a reverse as we now feel, happened; inasmuch as by far the greater part of their estates are let to such who are now so absolutely dispirited that they have not yet determined how low they would reduce their rents.

(p. 27) But I think I hear the landed gentry say, ‘Can you seriously advise us to lower our rents at least one third of their present value?’ No gentlemen, I am not so unreasonable. I would, on the contrary, wish to secure to you an advantageous and certain value of your lands independent of the accidental fluctuations of trade, without being exposed to the failure of the tenantry on the one hand or laying yourselves, as is now likely to be the case, at the mercy of a set of poor desponding, dispirited weavers who are for the present utterly unable to secure to you above one-half of your late rents. The farmer, such as I have mentioned, can very well afford to give you thirteen or fourteen shillings per English acre, and where he is not above one or two miles removed from good, natural manures, he will grow rich by it (if at a greater distance, some abatement should be made him) and I dare say that most gentlemen would be well satisfied with such rents. I know indeed some poor wretches who engage to pay twenty shillings and a guinea per (p. 28) acre; but they hold in general the third or fourth removed from the lord of the soil under a set of unfeeling task masters who keep them naked and half starved in a perpetual state of bondage. Would gentlemen take the trouble of informing themselves of the wretched condition of such people, they would not fail to prevent, by every public means, that kind of subdivision of their farms. But some mistaken advocates of the weavers will say, ‘What, sir, would you degrade this very useful body of men into the abject state of cotters?’ Mistake me not, good sirs, I look upon them as a very useful and necessary body and would go as far in their service as anyone, but yet I would not wish to see them landholders, not because I despise but because I love and esteem them and therefore would wish to see them employ their time more beneficially for themselves and their families than they can possibly do by attending to their little farms. I would have them live as weavers do in England, with plenty and comfort. I have travelled through a great part of the manufacturing counties there, not altogether an unattentive observer, (p. 29) and particularly in Yorkshire about Leeds, Wakefield and Halifax, and in Lancashire about Preston, Warrington and Manchester, I observed the country for some considerable distance round these towns to be thickly inhabited by weavers and I can with truth affirm that not one of those of whom I occasionally asked the question, possessed a single foot of land beyond a garden. The farmer supplied them daily with milk, butter, cheese, flour, potatoes etc. and the butcher with flesh meat; for there the weavers, except the dissolute and debauched, not only possess the necessaries but enjoy also many of the comforts and some few of the luxuries of life which are here the lot of only our wealthier folks and are utterly unknown to our weavers and small farmers. But many will ask, ‘How is this total change of things to be brought about?’ Not all at once I confess. Such an improvement must come by degrees. The landed gentlemen, were they even unanimous in desiring it, could not effect it of a sudden. Leases would interfere and render such a scheme for the present impracticable in its full extent. But something might be (p.30) done, even now, to open men’s eyes to their own interests. Many gentlemen have it at this instant in their power to let perhaps more than one such farm as I mention. Let them look out for an occupier and publish the conditions in England. Men of property and judgment might be found there who would consent to come among us for a good farm, especially if gentlemen could be prevailed upon to relinquish those slavish clauses which are now too generally introduced into leases such as duty work, with duty corn, and fowls, besides grinding our grain at certain mills at an extravagant price; terms and conditions utterly unknown among the sensible spirited gentlemen and farmers of England, which, while they strongly stigmatize the slavish souls of the wretches who submit to them, throw a shade on (otherwise) the fairest characters.

I am sensible of the delicacy of this subject and that it is scarcely possible to speak of it as the thing deserves without giving offence, where of all things I could wish to avoid it, and I know too how very (p. 31) difficult it is to get over the prejudice of old customs, especially where they seem to favour our interest. But my desire is by no means to abridge the landed gentry of any part of their revenues, On the contrary, I would wish to allow them the full value of their estates that they may be enabled to live with all that dignity, ease, and hospitality, which are so much the distinguishing characteristics of the gentlemen of this kingdom. The rents which they now receive under the slavish name of duties, I know do not exceed four-pence per acre and the forced rent of their mills cannot exceed two-pence more. Abolish these and we are ready and willing to advance your rents six pence per acre. The tenant who will not, let him continue still in fetters; he does not deserve to be free. Your mills, however, would still let at near two-thirds of their present value though not a single tenant were bound to them, and these would be more fairly and honestly dealt by if the millers knew they might go to what mill they pleased. But should it, upon trial, be found impracticable to induce an English farmer to settle among us from the horror he (p. 32) must conceive of the slavish condition of that state in this kingdom, I would advise to accept of the offer so often made by Mr Young of Northmines, and receive from him an intelligent husbandman to whom I would wish to see consigned the management of a farm of one, two, or three hundred acres; and by keeping an exact diary of the profits and expenses of a farm under such management, I doubt not it would be found more advantageous than any rent it would possibly let for either to weaver or farmer. A few such examples would soon be universally followed, and instead of that distress and misery which in our present low state of the linen trade we are daily witnesses to, we should soon see the whole face of the country changed, the rents liberal and well paid, the farmer enriched by plentiful crops, and the weaver with a full command of money to procure to his family all the necessaries and many of the conveniences of life. But I have occasionally heard it objected to this scheme that the experiment hath been already tried and found to be ineffectual. Some gentlemen, it is said, have been at the expense of (p. 33) building neat convenient factories for weavers to be supported merely by their loom and the experiment hath constantly failed. These objectors, however, must allow me to say that the gentlemen who have attempted such establishments have failed, not through any defect in the plan, but from an error in the execution of it. They have built factories, it is confessed, but have neglected to establish near them one or more sensible spirited farmers from whom their little manufacturing colony should have derived its support; whereas, were farms first settled, the weavers would have no avocation to take them from their looms, no temptation to call them from their natural employment, and would consequently greatly increase and improve our linen manufacture. The command of money which this increase of trade would give them, would be an alluring inducement to the farmers to vie with each other for their custom and thus these two very useful bodies of men would be linked together by the firmest bands of society, their mutual wants and interests.

(p. 34) It will not here, I hope, be required of me to prove that where men are wholly employed in the practice of any one trade they will make a greater proficiency and improvement in it than they could possibly do were their attention frequently called off to other pursuits. But should anyone be so unreasonable as to put me to the proof of it, I would beg leave to instance to him in the articles of pins or watches that the former, though seemingly of the most simple construction, is notwithstanding the work of several distinct trades not one of which infringes on the business of the other; the person who cuts the wire into proper lengths hath nothing to do with the polish or silvering of it; another gives it the point; a fourth forms the heads; and I believe a fifth puts them on. The watch-maker, too, buys his wheels from one, his chains from another; a third furnishes springs; a fourth provides screws; a fifth rivets and pins; and, if I am not mis-informed, that elegant, useful little machine is a composition of the joint labours of ten or a dozen different tradesmen. If any one doubts that both one and the other are better & cheaper than if they were (p. 35) the work each of one man, the watch- or pin-maker will soon undeceive him. But still there will be found many objectors to this plan merely on account of the novelty of it, or perhaps that they imagine that there can be no better method of cultivating the ground than the good old one which they see daily practised by men grown grey in the business of farming; They will not upon such occasions fail to instance a few men who have seemingly amassed wealth in the practice of it, not considering that among the very few who hold large farms of good land at a low rent and are worth, perhaps, two or three hundred pounds (here deemed a fortune), they cannot instance one who hath not had the advantage of some lucky hit in the linen-flax-seed, meal malting, or other trade, or perhaps hath dabbled not a little in lending out small sums at an exorbitant interest; or, in fine, saved a little money by living like a brute and denying himself all the comforts and many of the necessaries of life. Strip him of these helps and by the mere business of farming, as it is here practised, I will undertake to prove him to be no gainer. For instance in the single (p. 36) article of potatoes, that most useful, most beneficial of all roots, whether we consider it as food for man or beast or as the best preparation in nature for a subsequent crop of bere or barley, he cultivates them in the old lazy bed way, often without one single previous ploughing, but scarce ever more than one. Allured by the cheapness and ease of that slovenly kind of culture, and never keeping a register of the profits and expenses of his farm, he is well assured, by a gross guess, that by keeping them up to the spring season he can then sell them among the weavers and small farmers (for all others have enough for their own seed) at such a price as to give him some profit. But this method, besides that it doth not half labour or mellow his land, is so extremely slovenly and imperfect that it is next to impossible to keep it tolerably clean from weeds. For my own part, I never yet saw a subsequent crop of barley or wheat where I could not have traced the shape of the old potato ridge merely by the luxuriant growth of couch grass and other weeds, which had been pared indeed, but not eradicated from the brows or borders of (p. 37) the old ridges. Besides that, it is utterly impossible with that imperfect slovenly culture (if indeed it deserves the name of culture) to raise such a crop of potatoes as may enable the grower to sell them at a reasonable price to the consumer and to make at the same time such a profit by it as to pay the wear and tear of his horses and farming implements and to lay up anything towards defraying the charges of accidental contingencies.

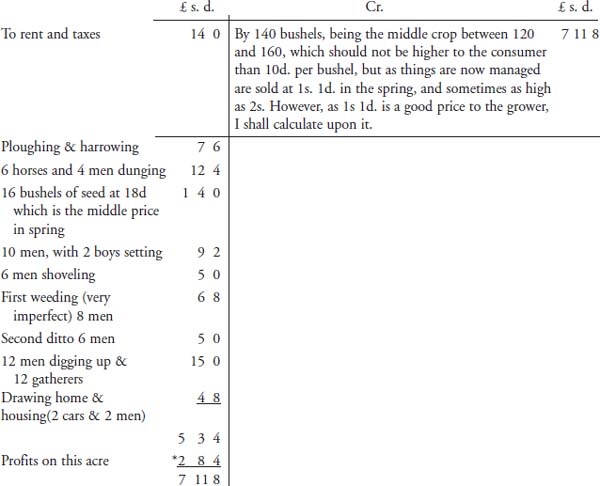

(4) Dr one acre of land cultivated in the most approved lazy-bed way

*When we reflect on the expenses attending this little crop, and that in every farm there must of necessity be some land from which the tenant cannot derive any the smallest profit, such as the land under drains and hedges, with that under his yard, buildings and high road; and that however diligent he may be, there will be still some part of his farm that is not worth the rent; that besides it will be almost impossible for (p. 39) him to provide manures for above one-tenth part of his land for the culture of potatoes. When all this is attended to, the profit of £2 8s.4d must be allowed to be very pitiful and trifling.

The author’s plan indeed is much more expensive, (about seven pounds to the acre) but his crops are answerable. He can prove beyond a doubt, that he raised 1351 bushels from two acres and one half of ground; his crop this year has every appearance of being much more considerable.

Upon the whole, though I have bestowed some pains in the investigation of this subject, as considering it (p. 40) of the utmost importance to this distressed country (nothing less indeed, than whether we shall become a wealthy, happy people, or dwindle from bad to worse into a state of absolute beggary and bankruptcy, to which we seem now to be hasting with great strides) yet will I not venture to conclude it to be wholly exempt from errors. Some it is possible there may be (though I am not conscious of any) because among those who here affect to call themselves farmers, there is not perhaps one (I am sure I know not one) who keeps a regular account of the profits and expenses of his farm.

But supposing, as I really do, that my premisses are right, the conclusions which I have drawn from them will, I hope, appear to be natural and unforced; and as I have no manner of interest in hazarding this little publication which may possibly provoke much censure from the better kind of people and abuse from the lower, the candid public will, I hope, excuse such inaccuracies as may be found in it.

FINIS

1 Printed for W. Watson in Capel Street, Dublin, 1783.