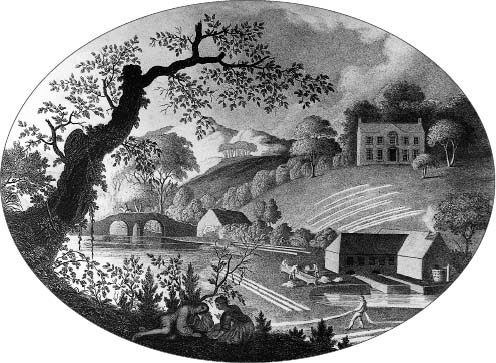

PLATE 10

Perspective View of a Bleach Green taken in the County of Downe, Shewing the methods of Wet and Dry Bleaching, and the outside View of a Bleach Mill on the most approved Construction …

WILLIAM HINCKS 1783

TRADITION GIVES THE CREDIT for the introduction of the flying shuttle into Ulster to the Moravian colony at Gracehill near Ballymena. The Moravians had established their colony in the townland of Ballykennedy on the O’Neill estate in 1759 and gained a reputation for their skill in textile crafts, especially needlework and later bone lacemaking.1 In 1816 S.M. Stephenson in an anonymous article in The Newry Magazine wrote:

The fly-shuttle was introduced from England into the Moravian settlement by Mr John McMullan, a member of that society. His object was to accommodate a linen weaver who had lost the use of his arm by a swelling in the joint. It was from thence transferred to Belfast, by the late Mr Robert Joy, of the house of Joys, McCabe and McCracken, about twenty-eight years ago [1788], and applied to the cotton loom. It by that means became generally known over Ulster.2

The Belfast News-Letter of 1 September 1778, however, ten years earlier than the date given by Stephenson, contains a letter addressed from Ballykennedy giving a detailed description of the technology involved in the flying shuttle:

We are glad to communicate to the publick the following account of the Flying Shuttle, for weaving linen, which has been introduced with success among the Moravians at Ballykennedy. If it be found to work as well as the common shuttle, the use of it will be attended with many conveniencies; particularly, as by means of it the weaver sits upright, (which is a much more healthful posture than the usual one,) and as persons who have lost the use of one of their arms may work at it without the smallest inconvenience.

A Description of the FLYING SHUTTLE [see Figure 10.1]

A board [D] is fixed on the under ball of the slays, about three inches and a half in breadth, extending twelve inches longer on each end than the under ball; the under ball must be cut down the depth of the thickness of the board, so that the edge of the board forms the side of the rabbit in which the reed is fixed: the board must be so fixed as to be level with the under part of the shade, when open, and close to the shade, but not so close as to press against the yarn. This board is of great use in the running of the shuttle, as it runs on it from one end to the other. On each end of the board is a box [E] about 14 inches long, from the middle of the slay-board until the end of the board: this box must be made just so wide that the shuttle can run in and out with ease, without having any room to spare. Over the middle of each box is an iron spindle, fastened at the extreme end of the box with a screw and at the other end fastened with a screw in the slay-board: on each of these spindles is a trigger [F] for driving the shuttle, the under end of which runs in a rabbit in the board or bottom of the box. To each of these triggers there is a cord, fastened to a piece of wood [B], which the weaver holds in his right hand, with which he pulls the trigger and drives the shuttle thro’ the shade. The running of the shuttle into the box takes the trigger into the far end of the box, for it must move with the least touch. The yoke of the reed must be level with the split of the reed, as must the slay-board and backside of the box, other-wise the shuttle would not run true. The shuttle is quite straight; the quill wound like a broach, does not run round, the thread running off at the end, goes out of the shuttle at the end of the shuttle-box; the waft comes off the quill much easier, and does not break, even when the yarn is very weak.

Our weavers are coming more into the use of this method of weaving: some of them can do a third more work than usual, and with a great deal more ease. It however suits coarse work best, as weaving with one stroke goes exceedingly quick, and with great ease. But the greatest advantage is in weaving check;3 for even where three shuttles are required, any of them can be brought to the shade as quick as the slays can fly.

No persons in this part of the country have yet tried this method, except our weavers. But I think it will by degrees come into general use.

BALLYKENNEDY,

AUG. 20, 1778.

As far as the weaver was concerned the most attractive feature about the flying shuttle was the consequent increase in the output of cloth. According to this account, production increased by a third. Yet in the long run the weavers must have been more grateful for being enabled to sit at their work instead of stretching over the loom passing the curved shuttle from hand to hand through the ‘shade’. This would have made it easier to work the treadles. It would also have eased the strain on the muscles of the lower back that must have resulted from weaving hunched forward over the older type of loom.

a. Front view of the batten of a loom showing the flying shuttle mounted as described in the letter: A, A, swords; B, hand-tree; C, reed; D, sley-sole or shuttle-race; E, E, shuttle-boxes; F, F, pickers.

b. Illustration of a shuttle as described in the letter: 1, quill; 2, yarn leaving the shuttle.

A postscript is provided by one of the early historians of the industry, Hugh McCall, in the third edition of his book Ireland and her Staple Manufactures:

The improved shuttle (known as ‘the shuttle with wheels’) was brought out by Mr McMullan, a gentleman engaged in the educational department of the Moravian colony at Gracehill, near Ballymena. ‘Mounted’ shuttles rapidly rose in popularity, and from thence the progressive class of weavers threw aside the old ones, and by the addition of still further improvements, Mr McMullan caused the little machine to be much sought after. He also instructed several mechanics in that neighbourhood in the new mode of shuttle-making. An ingenious person named Kelly, residing in Lisburn, became much celebrated for his work. His shuttles cost ‘five thirteens’, as the Irish crown pieces were called …4

1 Boyle, Elizabeth, The Irish Flowerers (Belfast, 1971), pp. 13–14, 33–5.

2 [Stephenson, S.M.,] ‘On the Antiquity of the Linen Manufacture, with Account of its Progress and Establishment in Ireland’, Newry Magazine 2, no. 9 (July and August 1816), 275, n.

3 The only surviving evidence about the manufacture of checks in Ulster about this period is to be found in the papers of the Adams family who lived at the appropriately named Chequer Hall at Ballyweaney in County Antrim: see Public Record Office of Northern Ireland D1518/2, Linen and general account book, c.1780–1830.

4 McCall, Hugh, Ireland and her Staple Manufactures (3rd edn, Belfast, 1870), p. 118.