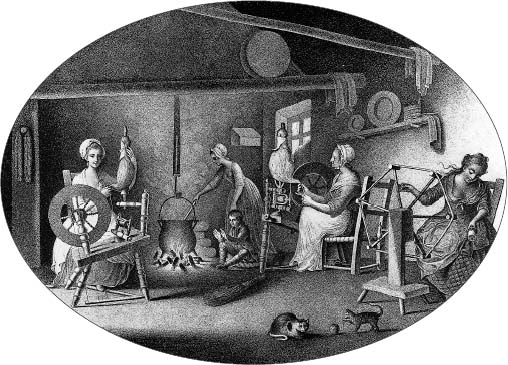

PLATE 6

Taken on the spot in the County of Downe, Representing Spinning, reeling with the Clock reel, and Boiling the yarn …

WILLIAM HINCKS 1783

IT IS SURPRISING THAT IRELAND has not attracted the attention of more economic and social historians in Great Britain. Content to accept what Dr Cullen has described as ‘facile generalisations about the Irish economy to which we have become accustomed’,2 based all too often on studies of the nineteenth century, they have not seriously examined Ireland within the larger framework of the British Isles. In American history the grafting of British civilisation on an alien culture, the influence on the colonists of their early struggle to establish themselves, and the effect of mercantilism on the colonial economy have been studied, but in Irish history the surface has only been scratched. In the context of contemporary discussions about the origins of the Industrial Revolution the sudden appearance and rapid growth of an important linen industry in Ireland must attract serious attention.3 The Irish Sea separated two different worlds and so the factors in the rise and development of the linen industry in such a colonial atmosphere, where its promotion with government support and under the aegis of the Linen Board was designed originally to strengthen the Protestant interest, differ in degree from those of a comparable industry in Britain. As Professor Charles Wilson has said: ‘The … expansion of the Irish linen trade forms a remarkable chapter in the economic history of the eighteenth century.’4

When William Hincks in 1783 published a set of twelve engravings depicting the various processes in the manufacture of Irish linen, he dedicated the first to the Lord Lieutenant, the second to the members of Parliament, the third to the trustees of the Linen Board and a further eight to various noblemen; only the twelfth and final engraving was inscribed to the linen merchants and manufacturers. Although Hincks was more concerned with potential patrons than with eulogies, any student of Irish life, aware of the influence of the landowner and the ‘big house’ in the community, would be inclined to accept these dedications at their face value: to him they are evidence of the authoritative role played by the landlord in the development of the linen industry. This view, however, would be an over-simplification, especially of social conditions in the province of Ulster, which was recognised as the home of the industry. It is time therefore to attempt an assessment of the influence of Ulster landowners in the rise of the linen industry; but the evidence has revealed that its rise seriously affected the influence of these landowners by encouraging the growth of an energetic and independent middle class, while it increasingly weakened the power of the landowners to control the development of their estates.

The birth of this industry lay in the Restoration period. Although previously the Irish had produced linen cloth for home consumption, they had exported considerable quantities of yarn only.5 Indeed this yarn surplus was one of the most important factors in attracting the immigration of skilled weavers from Britain into northern Ireland. In 1682 Colonel Richard Lawrence, who had managed a linen manu-factory for the Duke of Ormonde at Chapelizod near Dublin, wrote:

the Scotch and Irish in that province [Ulster] addicting themselves to spinning of linen yarn, attained to vast quantities of that commodity, which they transported to their great profit. The conveniency of which drew thither multitudes of linen weavers, that my opinion is, there is not a greater quantity of linen produced in like circuit in Europe: and although the generality of their cloth fourteen years since was sleisie and thin, yet of late it is much improved to a good fineness and strength.6

Settlement in Ireland was an attractive prospect to many British tradesmen; according to the English House of Lords in their petition of 1698 against the Irish woollen manufacture, ‘the growing manufacture of cloth in Ireland, both by the cheapness of all sorts of necessaries for life, and goodness of material for making of all manner of cloth doth invite your subjects of England, with their families and servants, to leave their habitations to settle there.’7 Land was very cheap in Ireland: on the Brownlow estate in north Armagh, where many immigrants from northern England settled, lands outside the town parks were let in the 1660s for 18d per acre and did not double in value until the first decade of the eighteenth century.8 At the same time religious persecution drove many Scottish Covenanters into Ireland and it was probably responsible for the large number of Quakers among the immigrants from the North of England who settled in the Lagan valley.9 These people found themselves at home in the Nonconformist atmosphere and in the exercise of their trades were untrammelled by English guild restrictions. Into this energetic and enterprising community was injected a Huguenot contribution of capital, new equipment and new techniques, with the official approval and support of the Dublin government.10

At least some of the Ulster landowners recognised the opportunities which had been presented to them. As early as the 1680s it had been forecast that by the linen manufacture ‘Ireland will soon be so enriched that in probability the price of land will bear double the value that it doth at present so that the nobility and gentry will be great gainers in particular.’11 The weakness of the landlords’ position was their lack of capital to invest in the industry. William Molyneux wrote to John Locke in 1696 that the noblemen and gentry had been admitted into a joint-stock corporation to promote the linen industry ‘more for their countenance and favour than for any great help that could be expected either from their purses or their heads’.12 If they had any spare capital he did not expect them to invest it in linen. Yet some of the landowners did offer the immigrant trades-men encouragement and leases on favourable terms. In the town of Lurgan, County Armagh, which was described in 1682 as the greatest centre of the linen manufacture in the north,13 Arthur Brownlow granted beneficial leases to tradesmen14 and deliberately stimulated the industry on his estate. He founded a linen market and until it was soundly established he bought up all the webs which were brought to it: at first he had lost money but later he made great profits.15 As a result Lurgan recovered very rapidly from the effects of the Williamite wars, with an increasing population, reflected in the building of more houses in and around the market place and in the extension of both the Anglican and Quaker houses of worship, so that in 1708 it was ‘the greatest mart of linen manufactories in the North, being almost entirely peopled with linen weavers’.16 A few miles away, Brownlow’s young neighbour, Samuel Waring, who had taken a tour through Flanders and the Low Countries about 1688, brought over a number of Flemish weavers from the Low Countries and settled them in Waringstown.17 Crommelin’s Huguenot colony in Lisburn was established with the support of Lord Conway who granted the French the site for their church: Lisburn was probably chosen by them because of its location in the heart of the linen-manufacturing area.18 Its destruction by fire in 1707 checked its progress, so that some of the weavers went to Crommelin’s brother’s settlement at Kilkenny and others ‘lodged themselves in Lurgan’.19 Yet the town was very soon rebuilt and in a short time regained its position as one of the chief markets in Ulster. The landlords of Counties Cavan and Monaghan were responsible for planting the industry in those counties. Dean Richardson, writing in 1740 to the famous scholar and antiquarian Walter Harris, referred to the success of the industry about Cootehill in County Cavan:

a good market house, a large market kept on Fridays in which there is plenty of provisions and abundance of good yarn and green cloth sold. There is a great number of weavers and bleachers in this town and neighbourhood and no less than ten bleach yards the least of which bleaches a thousand pieces of cloth every year. All which was brought about by means of a colony of Protestant linen-manufacturers who settled here on the encouragement given them by the Honble. Mr Justice Coote, who with a great deal of good management took care to have this new town so tenderly nursed and cherished in its infancy that many of its inhabitants soon grew rich and brought it to the perfection which it is now at; to which if we add the great pains that he took and the expense he was at in propagating this profitable branch of our trade thro’ other parts of the kingdom he may justly be called the Father of the Linen Manufacture in Ireland.20

The success of the industry in County Monaghan was attributed to several gentlemen:

The linen manufacture has made great progress in this county since the year 1703 by the industry and care of several gentlemen and particularly of Edward Lucas of Castleshane, Esq., who first introduced it, and for many years employed workmen and kept them under his own inspection.

Lucas is said to have introduced French and Dutch looms for his workers. Afterwards William Cairnes of Monaghan followed this example and settled this manufacture in the town of Monaghan.21

About this period the industry seems to have established itself throughout the rest of the province. There is evidence of a linen exhibition in Strabane in 1700, when local people were awarded prizes for their skill.22 In Coleraine the London-based Irish Society in 1709 had declined to encourage the manufacture of linen cloth,23 and yet by an Act of 1711 the name ‘Coleraines’ was applied to linens seven-eighths yard wide.24 In 1708 Antrim was ‘enjoying a considerable linen trade’.25 In the Ballymena and Cullybackey area the first bleachgreens date back to about 1705.26 The introduction of the weaving of diapers and damasks into north Down is ascribed to James Bradshaw, a Quaker from Lurgan who was persuaded by Robert Colville, the squire of Newtownards, to settle in that town in 1726.27 The linen industry was also given credit for signs of prosperity in Larne where it was reported that ‘a piece of forty hundred cloth manufactured in this town was made a present of to her Royal Highness the Princess of Orange at her wedding [in 1734]28 by the Trustees of the Linen and Hempen Manufactures being the finest then ever made in this Kingdom’.29

The success of these ventures induced the belief among landowners that any region could be improved by the introduction and expansion of the linen industry. Dean Henry, writing in 1739, noted that there was considerable trade in the linen manufacture throughout County Fermanagh, although Belturbet in County Cavan and not Enniskillen, the county town, was the chief market for counties Fermanagh and Cavan. He added, however:

these places might with a little encouragement be made rich by the linen-manufacture. Enniskillen might be a chief mart for it, the soil and flats about it being very good and convenient for bleachyards and the waters of Lough Erne having hereabouts a particular softness and sliminess that waters the flax and bleaches the linen in half the time that it can generally be done in other waters. It is not to be doubted but the happy national spirit for carrying on this manufacture and other useful branches of trade will in process of time exert itself properly along this lake as it has already done in other places.30

Unfortunately his dream never materialised.

About this time a number of serious attempts were made by landowners to sponsor the foundation of large manufactories. The most impressive to contemporaries was Lord Limerick’s project at Dundalk, where in 1736 the Huguenot de Joncourt established a factory for making cambric;31 it was probably in connection with this scheme that Harris noted in 1744 that a colony of fine diaper weavers had ‘lately’ been transplanted from Waringstown to Dundalk.32 The Archbishop of Armagh,

Primate Boulter … aided them materially by corresponding on their behalf with the government, as also in his office as one of the Trustees of the Linen Board; and, in addition to these efforts, he assisted in raising a subscription of £30,000 for the benefit of the settlement, which Lord Limerick encouraged in every way, by promising houses for the workmen, ground for the factory and a grant of ten acres for the sowing of flax.

It was later claimed that in a few years they had produced £40,000 worth of cambrics and lawns and that with the Board’s help they had started a manufactory of black soap for the bleaching industry.33 Although the factory was in operation in 1755, it had failed by 1776.34 It was probably the initial and much discussed success of the Dundalk venture which impelled Sir Robert Adair of Ballymena to write to John Reilly in Dublin in 1741:

I entreat you may if by any means possible to send me down by next post or the post following at farthest a proper draft of a subscription paper for establishing here a linen manufactory which can be done to great advantage in this place considering the many engines I have now fully fixed for that purpose which I am sure at present exceeds any in the Kingdom that is yet done.35

A linen manufactory was built in Hillsborough, County Down, by Lord Hillsborough, who later tried without success to encourage William Coulson of Lisburn to set up a damask factory there.36 The most famous of these schemes were not established in Ulster, however, although Ulster experts and weavers were settled on the lands: they were Sir Richard Cox’s great enterprise in Dunmanaway, County Cork37 and Lord Shelburne’s costly project at Ballymote in County Sligo.38

In contrast with the failure of these enterprises, sophisticated in their organisation and supported by substantial amounts of capital, was the growing success of the industry in Ulster where it had developed mainly on domestic lines. To the Lagan and upper Bann valleys the development of the industry brought increasing wealth, and competition forced up the value of land steeply. The conditions which the industry in this region required were explained by an agent in 1764 when advocating a scheme for the improvement of the estate and town of Rathfriland in County Down. In the first place, he pointed out, it was essential for the landlord to provide adequate market facilities. Then in order to persuade linendrapers to settle in the town and to build good houses, leases in perpetuity needed to be given for building plots, while the town parks could be let for profit for fixed periods; manufacturers of brown linens should be preferred when land was being let, not only because their competition would push up rents but also because they would stimulate the local markets for food, clothing and candles. As the whole tenantry paid their rents by some branch of the linen trade and were therefore not dependent on the land for their livelihood, only small areas needed to be leased to each individual at their full value, and so there would be no profit from subletting. On this point the agent noted:

The manufacturers of brown linen in the neighbourhoods of Waringstown and Lurgan, whose stock is barely sufficient to keep their looms in work and support their families, will give twenty shillings or a guinea per acre for a small farm with a convenient house thereon, and even at that price find it difficult to get proper accommodation …39

Since the closing years of the seventeenth century the houses in the town of Lurgan had been set in leases renewable for ever, but country leases to Protestants were for the term of three lives (the Penal Laws prevented Catholics from holding leases of more than thirty-one years). With the appearance of the bleach-mills requiring a more substantial investment of capital, linendrapers demanded much better terms. Harris attributed the success of the industry around Waringstown to the encouragement of long tenures:40 in Waringstown five leases made to linendrapers in 1720 and 1730 were for sixty-one years, but after 1736 leases were freeholds.41 Because of a minority between 1739 and 1747, it was not until 1748 that a spate of freeholds was granted to linendrapers in the Lurgan area: these took the form of three life leases renewable for a peppercorn, and the linendrapers paid substantial fines for them.42

Some landowners found at this time that their estate entails or marriage settlements prevented them from leasing land in freehold: both Lord Donegall in Belfast and Lord Hillsborough in north Down could grant leases of no more than three lives or forty-one years.43 It was therefore the landowners who successfully passed through Parliament two bills, which became Acts in 1764 and 1766, to enable themselves to break estate entails in order to grant leases of land not exceeding fifteen acres ‘for one or more lives renewable for ever or for any terms of years’ for the purpose of making or preserving a bleach-green.44 The substance of this provision was quoted by the agent John Slade to his master, Lord Hillsborough, in 1786, in an attempt to persuade him to grant a freehold lease to Messrs William and John Orr for a large cotton manufactory at Hillsborough to employ from two hundred to four hundred weavers and three times that number of women and children in spinning. However, although they proposed ‘to expend in building for their manufactory only at least £600, and if it succeeds to build handsome houses for their own habitation’, and although they did in fact purchase a house, they soon left the area because they had no lease.45

Landlords were stimulated, however, by the success of the industry and the attendant prosperity of the province, to indulge in schemes for town building, which produced important changes in the character of towns in this area. Harris recorded in 1740 that in the villages of Greyabbey and Saintfield in County Down proprietors had specifically built good houses ‘for the habitation of manufacturers’.46 Yet the finest achievements were the creation of the modern towns of Hillsborough in County Down about 1740 and Cookstown in County Tyrone about 1750. Lord Hillsborough gave:

great encouragement … to linen manufacturers. His Lordship has already erected two ranges of commodious houses, to each of which are annexed a garden and park of five acres, with ground for bleach greens at a convenient distance, and plenty of firing in the adjacent mosses.47

William Stewart of Killymoon Castle executed in Cookstown what has been described as ‘one of the boldest attempts at town building during the whole of Ulster’s history’:48 the magnificent main street, 130 feet in width and beautified with trees, runs in a straight line for a mile and a quarter. To provide water for the linen bleachers, he dammed a ravine above the town and so harnessed the river which was taken by a race to drive both cornmills and bleach-mills.49 Although the scheme was never completely realised, Cookstown and Dungannon, in which Lord Ranfurly had encouraged enterprise, were, with eight bleachyards apiece, the chief centres of the industry in County Tyrone in 1802.50

While many of these improvements remain as memorials to the efforts of the landlords, the most symbolic of all was the market house or linen hall. In Lurgan, ‘the greatest market for fine linens’ in the north, a market house built soon after the Restoration served until its destruction by fire in 1776 and was subsequently replaced by a linen hall.51 In 1728 Dublin White Linen Hall was built on the same lines as Blackwell Hall, the London centre of the woollen industry, suggesting that it was designed to fill a similar role in the Irish industry.52 The first linen hall (for brown or unbleached linens) in Belfast was built in 1738 with the help of Lord Donegall, who granted £1,500 towards its construction.53 By 1755 Lisburn (built by the Marquess of Hertford), Downpatrick (the de Clifford family), Strabane (the Earl of Abercorn), and Cookstown (Stewart) had their own halls or at least special facilities provided in the market house.54 Coleraine had two linen halls (one on each side of the River Bann) built in the last decade of the century, but because of the rivalry between their respective sponsors neither was used and the linen market was held in the street: the Marquess of Waterford had sponsored the erection of one, while a minor local landlord named Stirling built the other.55 In Londonderry the Hamilton family built a linen hall, but the Inspector-General in 1817 frowned on the Hamilton charge of 2d per web.56 Ballymena, Armagh, Newry, Limavady, Banbridge, Kircubbin, Ballynahinch, Rathfriland and Dungannon all had linen halls before 1810, most of which had been provided by the proprietor of the town.57

Resident landlords often displayed an intelligent interest in their markets and some landlords gave premiums to tenants for the production of high-quality flax, yarn and cloth. It was said of Lord Hillsborough and William Brownlow:

Both these landowners were well-known as being the most liberal patrons of flax-culture, flax-spinning and linen-weaving, as these industries existed among the tenantry of their respective estates. They gave liberal premiums for the largest and finest growths of flax produced by their tenants … Once a year three different classes of prizes were given, on the market day preceding Christmas, for the best ‘bunches’ of linen-yarn, and the prizes consisted not of money but of dress patterns, as well for maids as for matrons.58

Such interest in the trade was remarked on in 1817 by the Inspector-General appointed by the Linen Board for Ulster, James Corry: in Ballygawley, County Tyrone, he found that the proprietor of the town, Sir John Stewart, distributed premiums every market day ‘among the weavers who bring webs to the market of the best quality and in the greatest number – those premiums generally amount to £3, half of which is paid by the shopkeepers of the place, and the remainder by himself.’59 These demonstrations of enthusiasm tended to be confined to those landowners who believed that their encouragement would be reflected in their rentals and often evaporated if this object was not speedily realised.

It was not only landlords who were genuinely interested in the welfare of the industry on their estates that applied regularly to the Linen Board for allocation of spinning wheels and reels: some felt it incumbent on themselves to get as many as possible, even if it was only to demonstrate the extent of their influence in high places. In an amusing letter about the profits of office in Dublin, Charles Coote of County Cavan commented in 1748:

the business as usual is a series of jobs, the pleasure ends in awkward minuets and romping country dances; we begin to scramble for wheels and reels tomorrow and as soon as it is over I return to my much better business or more agreeable idleness in the country … if I get a tolerable harvest of wheels and reels I shall go home rejoicing.60

His cynicism was justified, because the Linen Board did not trouble even to keep track of the wheels. Robert Stephenson, the most able critic of the Board’s undertakings, exposed this abuse when he heartily condemned the Linen Board’s foolishness

to bestow money as cheerfully as we do, for spinning wheels, thousands of which lie idle and are spoiling for want of use in the garrets and outhouses of gentlemen, because they have neither material nor proper persons to employ them; and here we may reasonably enquire after spinning wheels, there being about 7,000 of them given away annually in three afore-mentioned provinces [Munster, Leinster and Connaught]; how are they employed?61

In the areas where the industry was increasing many landowners took full advantage of the grants. William Brownlow’s account books show that between 1771 and 1792 he received from the Linen Board at least £200 towards the purchase of wheels and looms: he was allowed £1 15s. 0d. each for thirty-three looms in the years 1775–7 and his rentals note more than twenty looms given to tenants. Five shillings was the grant for each wheel. In 1754 the absentee Earl of Abercorn’s agent asked him, ‘Will your Lordship be pleased to direct me how I shall dispose of the wheels [fifty wheels and ten reels], whether your Lordship would have them spun for, or divided amongst the poorer sort of tenant?’62 In a countryside where the linen industry flourished such gifts were considered as an investment in the estate, since they enabled poor tenants to pay their rents and reduced the number dependent on the parish.63

In the train of the linen industry came a revolution in communications in the north which seems to have got under way in the 1730s. The landlords were the foremost sponsors of this revolution and were active in presenting schemes for constructing roads and canals to open up the undeveloped countryside to trade and industry. They forced through an active policy of road construction, putting pressure on the parish vestries to improve local roads, submitting presentments to the grand juries for county roads, or promoting turnpike trusts. Harris commented on County Down in 1744: ‘As these roads cannot be well-repaired by the statute or day labour of the welders [sic] only, so the gentlemen of the county, who wish well to the commerce of it, now think it worth their attention to repair them by a county charge, which has been done to good advantage in other places.’64

The system of statutory labour was finally abolished in 1765. The roads from Dundalk to Banbridge and from Banbridge to Belfast had been placed under turnpike trusts by Acts of 1733, and two years later trusts were created for the roads from Newry to Armagh, Lisburn to Armagh, and Banbridge to Randalstown. For lack of sufficient revenue to pay interest on debentures and wages to officials even before the consideration of repairs, the turnpike roads tended to deteriorate more rapidly than the new county roads.65 Arthur Young commented in 1776 that the turnpikes were as bad as the by-roads were admirable.66

As early as 1699 the idea of a canal from Lough Neagh to Newry was seriously examined by a group of landowners which included Arthur Brownlow and Samuel Waring,67 and the region was mapped for the purpose in 1703 at the instance of several members of the House of Commons;68 again in 1709 Thomas Knox of Dungannon petitioned Parliament for its construction but without any success.69 The increasing exploitation of coal deposits in east Tyrone added much more weight to their arguments and with the foundation of the ‘Commission of Inland Navigation for Ireland’ in 1729 official approval was given to the scheme. Work commenced in 1731 but the first cargoes of coal from Coalisland in County Tyrone did not arrive in Dublin until 1742: even so it was the first major inland canal in the British Isles.70 The section of the Lagan canal from Sprucefield near Lisburn to Lough Neagh was completed in 1794, cost £62,000 and was constructed almost entirely at the Marquess of Donegall’s expense.71 The Strabane canal, first suggested to the Earl of Abercorn in the early 1750s,72 was not constructed until 1796: the then Marquess bore the total cost of £11,858.73 Although these eighteenth-century canals did play an important role in promoting the growth of the regions they served, they were eclipsed by the rapid expansion of the railway network in the mid-nineteenth century.74 It is significant, however, that Ulster landowners were prepared to advance so much for improvements in Ireland.

Some of the Ulster landowners were among the most active members of the Board of the Trustees of the Linen and Hempen Manufactures which had been established in 1711 to regulate the industry, to spread the knowledge of methods and technique throughout the country and to subsidise worthwhile projects. The Board tackled these tasks with enthusiasm but without sufficient knowledge of the trade; it did not ensure that the terms of its grants were fulfilled and so money was wasted; and in spite of its measures to encourage the industry in the south, the slump of the early 1770s almost obliterated the industry outside Ulster. Yet if the Linen Board had been more effective and able to regulate the industry as it pleased, there was a serious danger that its inexperience and lack of knowledge combined with an increasingly inflexible and bureaucratic approach to problems, would have imposed a strait-jacket on the industry. It was, for instance, fortunate for the industry that the Board was unable to enforce such of its regulations as concerned the reeling of yarn, the dimensions of cloth and the time and method of bleaching.75 The trade carried on by ‘jobbers’76 and ‘keelmen’ on the fringe of the industry was impossible to regulate and regularly condemned as illegal and yet it played an important role in serving the remoter districts and encouraged enterprise among the smaller dealers: it was reckoned in 1821 that in Armagh market, then one of the most considerable in the north, more than one-third of the dealers were ‘keel-men’.77

The Linen Board enjoyed great authority in its early years, especially when the Ulster landowners were most busily engaged in its support. They were very active in the House of Commons, particularly on committees which discussed the linen trade and relevant matters.78 Only through the landlords could the rising class of drapers make its demands heard. It was Brownlow of Lurgan who introduced the Linen bill of 1762 to regulate both the bleachers and the brown linen markets79 and in 1766 Thomas Knox of Dungannon (later Lord Ranfurly) wrote to Thomas Greer:

I … think myself much honoured by the respectable body of Linen Drapers, that thought proper to fix on me to present their memorial to my Lord Lieutenant. I beg you will assure them from me that I did with pleasure this day deliver it, and had the strongest assurance from his Excellency that he would recommend it to the Linen Board with all his power, which gives me reason to hope we shall succeed.80

John Williamson, an eminent linendraper from Lisburn, resented the condescending attitude adopted by the trustees when Henry Betty of Lisburn and himself tried to salvage the Linen bill of 1762 when it was dropped by the Commons:

We have carried everything we wished for. Very full boards of the trustees have sat nearly every day and tomorrow there is to be a final settlement. It is, however, my opinion that we would never have got a patient hearing, but would have been condemned and abused, had it not been for Lord Hillsborough, who has been our patron, our friend and adviser, in all cases. He received us as his children and since we came here he has laboured for us night and day, the effect of which has been that we are now treated with the highest respect by people who, when we came here, were ready to insult us … Many of the noble lords here would not vouchsafe to look on us, even though we worshipped them; they would suffer our cause to fail even though their own estates and the whole kingdom were equally involved in the same.81

Williamson, who was presented by the merchants of Dublin and London and by the linendrapers with a piece of engraved silver plate in recognition of his work on the 1764 Linen Act, was punished for his presumption by the Linen Board, who refused to grant him a white seal although every other bleacher in the kingdom had been furnished with one: the Board did not reply to a memorial submitted by the drapers on Williamson’s behalf and after a further petty insult Williamson went to live in London.82

Yet the landowners in Ulster were themselves well aware of the growing importance and influence of the linendrapers. On the Brownlow estate in north Armagh the most important men in the community were the wealthy linen-merchants and they were independent enough for Brownlow to cultivate their friendship and regard. During the 1761 election he had to quieten the fears of his partner Sir Archibald Acheson that their opponents, the Caulfields, were sounding out possible support among the Lurgan merchants and linen drapers: Brownlow’s local agent, the linendraper Jemmy Forde, had to make it clear to Maziere and Ruddle, two fellow linen-drapers who were disposed to listen to the Caulfields, that Brownlow was engaged to support Acheson and would have to share the expenses of the poll if one was necessary. Brownlow himself warned Acheson:

the people of substance here would, to be sure, wish to be conversed and to appear of consequence, which they cannot be without an opposition, and on that account grumble a little at your going on so smoothly but I shall take all the care in my power to make that ferment subside, and so strengthen your interest.83

In 1783 Thomas Knox of Dungannon professed friendship in his letters to the draper Thomas Greer, while apologising for being unable at the time to repay a loan of £1,000.84 In Strabane an even more powerful landowner, the Earl of Abercorn, had during the 1760s the greatest difficulty in his attempts to secure control of the corporation of Strabane, the chief town within his estates.85 The increasing authority of the drapers may have been responsible for the initial collapse of the 1762 bill over the clauses designed to regulate bleachers,86 but the real clash between the Linen Board and the drapers came twenty years later in 1782 over ‘Mr Foster’s’ Act.87 The bleachers and drapers had been consulted by a parliamentary committee before the bill was drafted and they expected a renewed campaign to tighten up the administration of the 1764 Act against the frauds of the brown-sealmasters (who examined unbleached linen), but they found that the whole burden of the Act was directed against them: although their trading reputation as responsible merchants should have guaranteed their products, they were to be held liable and punished for dealing in poor-quality cloth. As white-sealmasters they were to be strictly regulated: they would have to take an oath to obey all the Board’s rules and each man would have to provide not only bonds of £200 for his conduct but also two sureties who would guarantee him and bind themselves for similar sums. Although these clauses provoked angry reactions, the most serious of all was the Linen Board’s demand that each sealmaster had to perfect a warrant of attorney confessing judgement on the bond. This step would enable the Linen Board to adopt the simplest, quickest, and most economical method of securing all fines it might levy on the sealmasters: it would not be necessary to sue the sealmasters as by their warrant they had already admitted their liability to pay. The white-sealmasters objected that both the oath and the warrant bound them to obey without question any Act which the Board might introduce in the future no matter if they faced thereby the loss of their trade and the destruction of their livelihood, and several petitions on these lines were laid before Parliament. 88

The drapers were angry when they learned that their memorials, supported by their testimony before the Board, had been rejected out of hand and that instead a meeting of only five trustees on 23 July 1782 had decided to enforce the Act imposing a fine of £5 for each illegally sealed web; so they decided at meetings held in Lisburn, Lurgan and Newry that they would buy no more brown linens. At a meeting held by the Ulster drapers in Armagh on 5 August following, 437 drapers decided not to carry on trade until they obtained an assurance from the Linen Board that they would not be required to take the new oath or give any other than the usual simple bonds for their conduct. They further resolved ‘That whoever acts contrary to the general sense of the trade ought never to be considered as one of our body, or a friend to the linen manufacture of Ireland; nor will we on any pretence whatsoever bleach any linen for such persons who will not strictly and uniformly adhere to this our general determination.’89

In face of this opposition fifteen trustees (including only one of the original five and not John Foster, the real author of the measure) met two days later in Dublin, took into consideration the resolution at Armagh and revoked the order of 23 July on the grounds that no words appeared in the Act authorising or requiring the administering of the oath: if this was the case, however, it was a loop-hole in the Act.90 A meeting at Newry three days later refused still to resume trade, on the grounds ‘that the Linen Board have not yet given the trade satisfaction sufficient to enable them to proceed to business with safety’.91

At the same time, however, the drapers had found their own loophole in the Act and were trying ‘to procure five trustees who will join in issuing seals without putting the sealmaster to the severe qualifications required by the present Act of Parliament’. Five was the minimum number of trustees required by the Act to authorise appointments.92 Brownlow and Sir Richard Johnston were joined first by Lords Hillsborough and Moira and then by John O’Neill of Shane’s Castle (all Ulster landlords) as the five trustees.93 The Board had been forced to surrender. There is no doubt that, like the Irish Volunteers, the northern drapers had adopted the language and attitudes of the American rebels with success. The lesson had not been lost on John Nevill, the self-appointed advocate of the drapers’ cause: ‘the stubborn perseverance of enforcing an Act of Parliament lost Britain the greater part of her dominions; there is no reason to believe that the experiment will be attempted on the trade of Ireland.’94

From this time the independence of the northern drapers became more pronounced. Later in the same year it was decided to build a white-linen hall in Ulster to sell white linens in the heart of the manufacture: it was unnecessary to send linens to Dublin when they could be shipped from Belfast or Newry.95 Underlying these valid arguments was a certain resentment felt by the Ulster drapers against the authority of the Dublin factors and this was expressed in the grumble that the government in Dublin paid more attention to the views of the Dublin factors than to those of ‘the most eminent drapers in the country’.96 By 1785 white-linen halls were open in Belfast and Newry: although the Newry hall soon failed that in Belfast grew steadily at the expense of Dublin.97

The Act of Union (1800) saw the end of the Irish Parliament and a subsequent decline in the influence of the Board of Trustees: Dublin was no longer the centre of government which attracted active personalities and it became more and more divorced from the industry. The Board was still the guardian of the linen trade but now its meetings were very sparsely attended and in some years there was not a quorum of twelve.98 It was run by John Foster (now Lord Oriel) and its secretary James Corry, both of whom showed energy and initiative in making grants for the erection of scutch mills to prepare flax for the spinners.99 Yet they could only subsidise, not initiate, changes in the industry. One of the arguments used by an English manufacturer to dissuade an Irishman thinking of establishing a spinning mill at Dundalk in 1801 was that ‘the premium to be expected from the Linen Board would be of little importance compared with the eligibility of the scheme’:100 the optimism of the mid-eighteenth century had submitted to the realistic assessment of the nineteenth. The Board itself was increasingly under fire for inefficiency, jobbery and ostentation;101 even Foster was forced to recognise the justice of these criticisms when he complained in 1819: ‘It strikes me that the flax seed inspectors ought not to take advantage of the two Acts of 1802 and 1804 to do an act to put money in their own pockets without any advantage to the trade or any additional security against the sale of bad seed to the grower.’102

It is not surprising that one of the fiercest diatribes against the Board came after its decease from the Lisburn historian of the industry, Henry McCall (1805–97):

The Board of Trustees — the supreme authority on all questions — issued their decrees with the pomposity of three-tailed bashawism. Their dogmas dare not be disputed; and the secretary of that formidable cabinet, Mr James Corry, made his tour of the provinces in semi-regal state, the county inspectors, the deputies, and sealmasters forming his body-guard in every market town which he honoured with a visit. All this complicated and cumbrous machinery was kept in motion at great cost, and it was only when forward men arose and stood against such mischievous meddling, that the trade was emancipated from its trammels.103

The forward men had their reward in 1828, when the government withdrew its grants from the trustees and the Linen Board ceased to function.

Yet early in the nineteenth century the domestic linen industry reached its peak and played a very important role in the economy of the Ulster countryside. The rapidly increasing population was already pressing hard on the resources of the land in Ireland; emigration had eased the pressure on Ulster but modern industry had scarcely made its appearance and natural controls had not yet operated to check the growing numbers. As a result many small farmers and their families were forced to take up the linen industry to make a living, although as contemporary observers noted, weavers might earn no more than day labourers.104 The organisation of the industry in Ulster had become so efficient that it was able to cope with the increasing production of the remoter areas and to give the North the relative appearance of prosperity which so impressed travellers after their experiences in the south of the country.105

How the linen industry and changing conditions on the land interacted may best be learned from an examination of four distinct regions. Around Belfast by 1800 the majority of handloom weavers relied on manufacturers for regular employment and the supply of raw materials, so that the cotton industry was replacing the linen industry and encouraging many men to break their final ties with the land.106 Away from the coast, however, in north Armagh and west Down observers were surprised to find that highly skilled linen weavers were often independent of the manufacturers and still farmed smallholdings. Further south in Cavan and Monaghan such small-holdings were usually leased directly from landlords by weavers of coarser linens and were the prevalent features of the rural scene. In the rest of the linen country in Counties Antrim, Londonderry, and Tyrone, the weavers were usually cottiers dependent on weaving to supplement their earnings on the land. On the verge of poverty lived the weavers in mountainous districts, compelled to rely on the markets for their supplies of flax and thread which they themselves could not produce.107

The heart of the industry lay in the triangle between Lisburn, Armagh and Dungannon and there the independent craftsmen secured small parcels of land in the vicinity of a good market town as they were able to pay a higher rent than any farmer who was prepared to earn his living by farming alone. A study of estate rentals and leases on Brownlow’s manor of Derry shows that when leases expired the previous sub-tenants had been taken on as full tenants because they were able individually to offer a higher rent than a middleman.108 In this way Brownlow and landlords who adopted a similar policy had been able to take advantage of the rising value of rents but they were prepared in turn to grant to good tenants long secure leases instead of mere tenancies at will. The landlords’ readiness to lease holdings direct to sub-tenants forced out the middleman or the original holder of the grand lease who was thus deprived of what had been a valuable and easy source of income. As a result there were in this region by 1800 very few substantial farmers and even fewer minor gentry: most of the gentry owed their prosperity to wealth acquired from trade or the professions or indirectly from the profits of the linen industry.

Although observers like Arthur Young and Sir Charles Coote were convinced that in such circumstances agriculture must suffer as the skills of weaving and farming could not be combined,109 the weaver took a different view. If he grew his own flax he could employ the skill of his womenfolk to spin the very fine threads needed for his cambrics and lawns while he had turbary rights and enough grass for one or two cows: on a farm of ten acres two cows would supply a family with milk for a year and one hundredweight of butter to sell in the market. It is not surprising then that the linen country was noted for its dairy farming and supplied the Lagan valley and Belfast.110 Here the weaver knew too that he could turn to farming during slumps in the industry which occurred more frequently as the market for expensive fine linens was more liable to saturation than that for coarse linens; he was also able to cushion himself against the fluctuating price of oatmeal, his chief article of diet, especially during bad seasons. Coote himself did admit that he believed ‘that the people would rather have nothing to do with agricultural pursuits if the markets were more numerous and constantly supplied with provisions’; besides, too much farming rendered their hands unfit for weaving fine linens.111

In south Armagh, Cavan and Monaghan, the southern counties of Ulster, where the population density often exceeded four hundred persons to the square mile, the lot of the farmer-weavers was harder. The weavers manufactured the cheaper coarse linens while their farming was very poor and reflected none of the more modern techniques. Of the barony of Tullaghonoho in County Cavan Coote reported: ‘Here there is no market for grain … They breed but very few horses here, and less of black cattle; tillage is their principal pursuit, and they cultivate now no more of provisions than they require for themselves, their great concern is flax-husbandry and the linen-manufacture’, and complained: ‘In so many thousand acres now occupied by very poor weavers we rarely see better than black oats, of an impoverished grain, which are capable of yielding the finest wheat, or could certainly be converted to the best sheep-walk.’ Pressure of population had reduced the weavers to subsistence level and the standard of agriculture to such a condition that the landlords did not attempt to introduce improvements and often did not even trouble to renew leases but permitted them to continue as tenancies at will after they had lapsed.112 The tenants, on the other hand, feared that improvements would only mean increased rents and tithes.113

In this region there were also many cottiers; but cottiers were much more numerous in the northern counties of Antrim, Londonderry and Tyrone, where they were employed by farmers and manufacturers. These counties contained a larger percentage of more substantial farmers than anywhere else in the province and in the Bann and Foyle valleys they farmed some of its best agricultural lands. Young noticed in 1776 that the farmers in north Londonderry concentrated on farming and gave out to weavers the yarn their womenfolk had spun.114 Dependent on such farmers or on linen manufacturers for employment, the cottier tenants secured scraps of land on which to graze a cow and grow potatoes and although they were given no title to the land they paid exorbitant sums for it or worked for their landlord.115 Whether their employer was a manufacturer or a farmer the cottiers were at his mercy in their pursuit of a livelihood and they were exploited; of County Londonderry in 1802 it was reported:

In many districts the cottier could not hold out but for the liberal wages of linen merchants and other gentlemen … I assure the reader that the grass of a cow, which three or four years ago was valued at 20s is now raised to two guineas even on the bare moors where the poor animal is tethered and where she has better opportunity of grinding her teeth on the sand than of filling her belly with pasture.116

Often they owed arrears of rent to their employers. When farmers wanted to consolidate and improve their farms it was easy for them to remove cottiers since they had no rights to their land. One observer noticed in 1813 that the population of Omagh was increasing ‘not only on account of the linen and other manufactures there carried on, but also by reason of the people here, as almost everywhere, being driven from their farms into towns by monopolizing farmers’.117 But the small provincial towns could not absorb such large-scale immigration.

Such was the condition of the industry throughout Ulster on the eve of the introduction of machinery. The first dry-spinning mills had appeared in Ulster soon after 1800 but for twenty years they made little progress because of the low cost of labour in Ireland: indeed the spinning women were often forced to cut their losses by disposing ‘of the worked article for less than the raw material cost them’, and it was said that the women regarded it as ‘an alternative to idleness’ rather than a paying pursuit.118 When the more efficient process of wet-spinning displaced dry-spinning the domestic industry soon vanished, with a consequent decline in the rural standard of living. Soon after 1850 the introduction of the power-loom finally destroyed the livelihood of the handloom weavers.119 Their numbers declined so rapidly that by the early twentieth century only the finest damask tablecloths were still woven by hand.

Irish landlords had promoted the linen industry to improve their estates: that they succeeded in Ulster their substantial rentals will testify. This does not mean that the tenants on their estates benefited to the same extent. To the region bounded by the triangle of Belfast, Armagh and Dungannon where skilled weavers from England, Scotland and France had congregated, the industry brought increasing wealth but in the surrounding counties it had become by 1800 a means of supplementing farming incomes and with the rapidly increasing population had artificially inflated the value of lands where improved methods of farming had never been adopted: there it depressed the standards of agriculture and the subsequent decay of the domestic linen industry left these remoter districts in comparative poverty. It may be true also that the spread of the industry had hastened the collapse of the manorial system originally introduced into Ulster by the English government and the planters early in the seventeenth century, but before we can make a judgement, much more detailed investigation of estate records will be required: linked with this is the problem of land tenure and the evergreen topic of Ulster tenant right and its origins. There is no doubt, however, that the rise of the linen industry produced from the descendants of yeoman and tradesmen a new wealthy class which in 1782 successfully challenged the authority of the Linen Board to dictate the conditions under which the industry should operate. It would be interesting to find out the extent to which linendrapers were involved in the United Irishmen as their successful opposition to government interference in industry may have been reflected in a radical approach to politics. To the Ulster linen industry must be attributed the creation of conditions in which the cotton industry flourished for a time, and indeed it played an important part in laying the foundations for Belfast’s rise to eminence in the nineteenth century. With the subsequent establishment of the factory system in the linen industry, however, the landlord’s interest in it faded.

1 First published in J.T Ward,. and R.G. Wilson, (eds), Land and Industry: the Landed Estate and the Industrial Revolution (Newton Abbot, 1971), 117–144.

2 Cullen, L.M., ‘The value of contemporary printed sources for Irish economic history in the eighteenth century’, Irish Historical Studies, 14 (1964), 155.

3 The only full-scale treatment of the industry in the eighteenth century is contained in Conrad Gill, The Rise of the Irish Linen Industry (Oxford, 1925, reprinted 1964). See also E.R.R Green., The Lagan Valley, 1800–1850 (London, 1949) and The Industrial Archaeology of County Down (Belfast, 1963).

4 Wilson, C., England’s Apprenticeship, 1603–1763 (London, 1965), p. 198.

5 Rawlinson MSS (Bodleian Library, Oxford) D 921, fo. 147 (transcript in PRONI T545/8) ‘Proposals for the cultivation of flax and hemp in Ireland’ (undated, but Dr Cullen believes that internal evidence points to a date early in the 1680s), 3.

6 Lawrence, Richard, The Interest of Ireland in its trade and wealth stated (Dublin, 1682), vol. 2, 189–90.

7 House of Lords’ address to King William III, 9 June 1698. published in A. Young, Tour in Ireland (Hutton, A.W., 1892), vol. 2, 193.

8 Brownlow MSS (PRONI) T970, Arthur Brownlow’s lease book.

9 There were strong Quaker communities in Lisburn and Lurgan: their first meeting in Ireland was formed in 1653 at Lurgan by William Edmundson, a Cromwellian soldier. See Quaker meeting records (PRONI T1062 and Mic/16).

10 Gill, op. cit., pp. 16–20.

11 ‘Proposals for the cultivation of flax and hemp in Ireland’, p. 10.

12 Quoted in W.R. Scott, ‘The King’s and Queen’s Corporation for the linen manufacture in Ireland’, JRS Antiq. Ire., 5S, p. 11 (1901), 371.

13 William Brooke to Dr William Molyneaux, published in ‘An account of the Barony of O’Neiland, Co Armagh, in 1682’, Ulster Journal Arch., 2S, 4 (1898), 241.

14 Arthur Brownlow’s lease book, 87. Lurgan Quaker Records note a 1695 lease of a tenement in their account of the rebuilding of the meeting-house. Both the Quakers and Brownlow regarded these leases as copyholds: they were not fee-farm grants but leases for three lives renewable on the fall of each life with fixed rents and renewal fines and subject to the usual duties of the manor, especially suit to courts and mills.

15 Thomas Molyneux, ‘Journey to the North, August 7th 1708’, in Historical Notices of Old Belfast and its Vicinity (ed. R.M. Young, Belfast, 1896), p. 154.

16 Molyneux, op. cit., p. 154.

17 Atkinson, E.D., An Ulster Parish (Dublin, 1898), p. 49.

18 McCall, H., Ireland and her Staple Manufactures (3rd edn, Belfast, 1870), p. 40.

19 Louis Crommelin to Duke of Ormonde, 24 May 1707, Ormonde Calendar, ns, no. 4, 299.

20 Lodge MSS (Armagh Public Library) Bundle no. 35, ‘Cavan’ in bundle of Topographical and Statistical returns from various respondents sent to Walter Harris and the Physico-Historical Society of Ireland circa 1745.

21 Lodge MSS, Bundle no. 35, ‘Monaghan’. Mr William Cairnes, a Dublin merchant, bought the Blaney estate in County Monaghan in 1696; two of his brothers were London merchants. See H.C. Lawlor, A History of the Family of Cairnes or Cairns (1906), pp. 82, 83.

22 Abercorn MSS (PRONI) D623/47; this is confirmed by Molyneux, op. cit., p. 159.

23 A. Marmion, The Ancient and Modern History of the Maritime Ports of Ireland (1855), p. 383.

24 9 Anne c. p. 3.

25 Molyneux, op. cit., p. 156.

26 Lawlor, H.C., ‘Rise of the Linen Merchants in the Eighteenth Century’, Irish and International Fibres and Fabrics Journal, 7 (1941) p. 11; 8 (1942) 44.

27 Harris, W. and Smith, C., The Antient and Present State of the County of Down (Dublin, 1744), p. 56; Green, County Down, 29; Londonderry Estate MSS (PRONI) D654/LE36A/10 and D654/LE31/1.

28 In 1734 Anne, Princess Royal as eldest daughter of King George II, married the Prince of Orange.

29 Henry William ‘Henry’s Topographical Descriptions’ (a bound manuscript in APL), 142.

30 Henry, op. cit., 96.

31 Gill, op. cit., p. 154.

32 Smith and Harris, op. cit., p. 104.

33 Purdon, D.C., communication to Journal of the Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, 3rd S, 1 (1868), 17–20.

34 Young, op. cit., vol. 1, 115.

35 Adair MSS (PRONI) D929/F4/1/15.

36 Smith and Harris, op. cit., p. 95; McCall, op. cit., p. 126.

37 A Letter from Sir Richard Cox, Bart, to Thomas Prior, Esq, showing a sure method to establish the Linen Manufacture (Dublin, 1749) (Hanson 6242).

38 Young, op. cit., vol. 1, 223–30; Greer MSS (PRONI) D1044/52.

39 PRONI T1181/1.

40 Smith and Harris, op. cit., p. 105.

41 Leases made by Samuel Waring and recorded in the Registry of Deeds, Dublin:

| BOOK | PAGE | NUMBER | LESSEE | TERM | YEAR |

| 62 | 4 | 41615 | Thomas Waring | 61 years | 1729 |

| 62 | 4 | 41616 | Henry Close | 61 years | 1729 |

| 64 | 504 | 44915 | John Murray | 61 years | 1730 |

| 69 | 321 | 48537 | Mark Gwyn | 61 years | 1732 |

| 72 | 43 | 49626 | Thomas Factor | 61 years | 1730 |

| 84 | 356 | 60015 | Thomas Waring | For ever | 1737 |

| 87 | 174 | 61151 | John Houlden | For ever | 1736 |

| 114 | 340 | 79161 | Robert Paterson | 1744 | |

| 121 | 98 | 82221 | Samuel Paterson | For ever | 1745 |

42 Brownlow estate papers (PRONI):

Brownlow to David Maziere for land in Derrymacash and Derryadd (1755)

Brownlow to James Bradshaw for land in Drumnakelly (1750)

Brownlow to Henry Greer for land in Dougher (1759)

Registry of Deeds Book 139, p. 68, no. 92984 to Henry Greer (1749)

Registry of Deeds Book 135, p. 452, no. 92216 to James Greer (1749)

Registry of Deeds Book 143, p. 208, no. 96608 to David Ruddell (1750)

Registry of Deeds Book 143, p 209, no. 96611 to James Forde (1750)

Registry of Deeds Book 193, p 106, no. 127135 to Ben Hone (1757)

43 Donegall MSS (PRONI) D509/129; Downshire MSS (PRONI) D607/259A, John Slade to Lord Hillsborough 20 Feb. 1786.

44 3 Geo. III, c. 34 and 5 Geo. III, c. 9, s. 4.

45 Green, op. cit., p. 26.

46 Smith and Harris, op. cit., pp. 49, 71.

47 Ibid, p. 95.

48 Camblin, G., The Town in Ulster (Belfast, 1951), p. 81.

49 Article in MidUlster Mail, 12 Sept. 1925 (PRONI T1659).

50 McEvoy, J., Statistical Survey of the County of Tyrone (Dublin, 1802), pp. 138–9, 158.

51 Lurgan town lease no. 103. It is surprising that Arthur Young, who visited the linen market a month after the fire, did not comment on it.

52 Gill, op. cit., pp. 79–81.

53 Young, R.M. (ed.), Town Book of Belfast, 1613–1816 (Belfast, 1892), p. xii.

54 Pococke, R., Tour in Ireland in 1752 (ed. G.T. Stokes, Dublin, 1891), p. 13 (Downpatrick); Abercorn MSS T2541/1A1/2/31 and p. 34.

55 Corry, James, Report of a tour of inspection through the province of Ulster (Dublin, 1817), App. 94. PRONI D699/5. Will of Robert Rice, 6 Oct. 1800.

56 Corry, op. cit., App. 91.

57 Ibid., Apps 12 (Dungannon), 59 (Banbridge), 71 (Ballynahinch), 75 (Kircubbin), 83 (Ballymena); Marmion, Maritime Ports of Ireland (Newry), p. 314; Boyle, E.M., Records of the town of Limavady, 1609–1808 (Londonderry, 1912), p. 98; Lewis, S., A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837), vol. 1, 68; vol. 2, 498.

58 Green, W.J., A Concise History of Lisburn and Neighbourhood (Belfast, 1906), p. 30.

59 Corry, op. cit., p. 76. See also his references to Monaghan (p. 75) and Enniskillen (p. 84).

60 Charles Coote to Earl of Abercorn, 31 March 1748 (Abercorn MSS, T2541/1A1/1D/13).

61 [R. Stephenson] Remarks on the present state of the linen manufacture of this Kingdom (Dublin, 1745), 13. Stephenson’s career and his influence over the policies of the Linen Board are examined in some detail in Gill, op. cit. pp. 96–7.

62 Abercorn MSS, T2541/1A1/2/44/175.

63 Stephenson, R., Considerations on the present state of the linen manufacture (Dublin, 1754), p. 21.

64 Smith and Harris, op. cit., p. 77.

65 Commons’ Journal Ire., VII, pp. 51, 112, 113, 192; VIII, 468, 495, 501–2 (dealing with the problems of the Lisburn to Armagh turnpike).

66 Young, op. cit., vol. 2, 7. See also vol. 1, 116.

67 Waring MSS (PRONI), D695/51, Arthur Brownlow to Samuel Waring, 27 August 1699.

68 Waring MSS D695/M/1.

69 McCutcheon, W.A., The Canals of the North of Ireland (Newton Abbot, 1965), p. 63.

70 Ibid., pp. 11, 20.

71 Ibid., p. 45.

72 Abercorn MSS, T2541/1A1/2/149.

73 McCutcheon, op. cit., p. 86.

74 Ibid., p. 16.

75 Gill, op. cit., pp. 150–51.

76 ‘Jobbers’ bought webs in outlying markets to sell them in the chief centre of trade: their existence was vital to the small markets. Gill, op. cit., pp. 170–2.

77 ‘Keelmen’ were dealers who bought cheap coarse cloths in the local markets and retailed them in Britain. J. Corry, Report on the measuring and stamping of brown linen sold in public markets (Dublin, 1822), App., pp. 174–5. See Appendix 5.

78 Commons’ Journal Ire., III, 31, 251; IV, 13, 337; V, 228.

79 McCall, op. cit., p. 74.

80 Greer MSS, D1044/92.

81 McCall, op. cit., pp. 74, 75.

82 Ibid., pp. 84–7.

83 Gosford MSS (PRONI), D1606/1/21 March 1761.

84 Greer MSS, D1044/692. See also D1044/677A.

85 Abercorn MSS. The correspondence for 1764 contains many references to this struggle since it lasted throughout the year.

86 McCall, op. cit., p. 74.

87 Gill, op. cit., p. 206.

88 Massereene MSS (PRONI) D207/28/3, 99, l00, 101; Greer MSS, D1044/899. The row is discussed in detail in Nevill, John, Seasonable remarks on the linen trade of Ireland (Dublin, 1783).

89 Massereene MSS, D207/28/3.

90 Ibid., D207/28/99.

91 Ibid., D207/28/100.

92 21 & 22 Geo. III, c. 35, s. 9.

93 Massereene MSS, D207/28/100; Greer MSS, D1044/899.

94 Nevill, op. cit., p. 39.

95 Ibid., pp. 68, 69; Greer MSS, D1044/900.

96 Nevill, op. cit., p. 52.

97 Gill, op. cit., pp. 189–91.

98 Massereene MSS, D207/28/272.

99 Ibid., D207/28/249A.

100 Ibid., D207/28/113.

101 Ibid., D207/28/249A.

102 Ibid., D207/28/214.

103 McCall, op. cit., p. 243.

104 Wakefield, E., An Account of Ireland (London, 1812), 700.

105 Beckett, J.C., The making of modern Ireland, 1603–1923 (London, 1966), p. 180.

106 Green, Lagan Valley, p. 99.

107 McEvoy, op. cit., p. 200.

108 Table based on PRONI D1928/R/1/ Rentals, the rentals of the Brownlow estate (1755–94) to show changes in the size of holdings in statute acres:

| 0–5 | 5–10 | 10–20 | 20–50 | 50–100 | 100+ | Total | |

| 1755 | 10 | 31 | 55 | 55 | 34 | 14 | 199 |

| 1765 | 14 | 34 | 75 | 49 | 35 | 13 | 220 |

| 1775 | 27 | 52 | 83 | 42 | 19 | 11 | 234 |

| 1785 | 56 | 114 | 113 | 53 | 12 | 5 | 353 |

| 1794 | 70 | 153 | 115 | 49 | 12 | 5 | 404 |

Note: Of the leases in 1785 eight were perpetuities, 196 were for terms of three lives, 78 for thirty-one years and 9 for twenty-one years while 60 had no lease. In 1765 and 1775 the number of tenants without a lease had been 10.

109 Young, op. cit., vol. 2, 215–17; Coote, Sir C., Statistical survey of the county of Armagh (Dublin, 1804), pp. 261–7.

110 Green, Lagan Valley, p. 142.

111 Young, op. cit., vol. 1, 134.

112 Coote, Sir C., Statistical survey of the county of Cavan (Dublin, 1802), pp. 108–9, 151, 157.

113 Hall, Rev. J., Tour through Ireland (London, 1813), pp. 116–17.

114 Young, op. cit., vol. 1, 165.

115 McEvoy, op. cit., pp. 99–100; Dubourdieu, Rev. J., Statistical survey of the county of Antrim (Dublin, 1812), p. 147.

116 Sampson, Rev. G.V., Statistical survey of the county of Londonderry (Dublin, 1802), p. 298.

117 Hall, op. cit., p. 118.

118 Wakefield, op. cit., p. 684; Green, Lagan Valley, p. 116.

119 Johnson, J.H., ‘The population of Londonderry during the great Irish famine’, Econ. Hist. Rev., 2S, 10 (1957), 272.