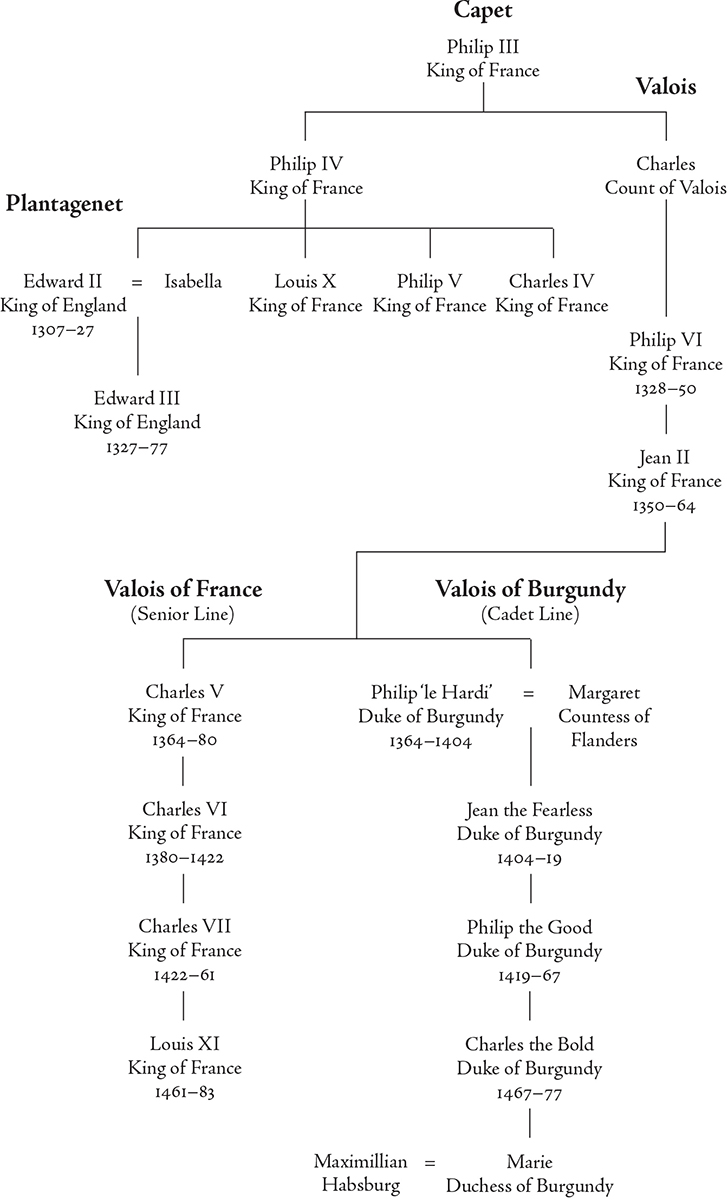

The Houses of Capet, Plantagenet and Valois

MANY medieval and early modern empires were founded on the sterility of princely houses. Kingdoms and principalities that resisted conquest for centuries were gobbled up whole if their ruling dynasty died out. Whenever a prince failed to provide a legitimate heir, greedy relatives and neighbours could soon be seen circling him like a pack of vultures, and conquest or civil war were bound to follow. When a prince sired only daughters, he was just as quickly surrounded by suitors, anxious to put their hands on the dowry. It was in such a way that Scotland and England, and Aragon and Castile – hitherto bitter enemies – found themselves united into Britain and Spain. It was in such a way that the Habsburgs constructed the greatest empire of the early modern age.

During the late Middle Ages no dynasty preyed on its infertile neighbours with more ruthlessness and success than the Valois of Burgundy. Since their stepping stones to empire were the heads and wombs of princes and princesses, the focus of their military efforts too was on these heads and wombs as much as on armies and fortresses.

The house of Valois was a cadet house of the Capetians, the ruling dynasty of France since 987. (See genealogical table overleaf.) It came to power in 1328 when the last Capetian king of France, Charles IV, died without leaving any male heir. The Capetian inheritance – which constituted the most powerful kingdom in Christendom – was then disputed between Charles IV’s cousin, Count Philip of Valois, and his nephew, King Edward III of England. Philip won, due to a combination of many causes, but the legal excuse given was that Edward had inherited his claim to the French Crown through his mother, and in the Kingdom of France, a female could allegedly neither inherit land nor pass rights of inheritance to her sons.

Philip’s son, King Jean II of France, fathered a number of sons, and while the crown went to the eldest, each of the others was compensated with a dukedom. One of these younger sons, Philip ‘le Hardi’, received the duchy of Burgundy. Soon after, he married the richest heiress of his time, Margaret de Mâle. She inherited from her father the County of Artois, the Franche-Comté and above all the rich County of Flanders – the most urbanized and industrialized area of medieval northern Europe. Thanks to his wife’s rich dowry, Philip was transformed from just another duke amongst many into one of the foremost princes of Christendom and the most powerful force in French politics. (See map 4.)

When in 1392 the young king of France went mad, Philip ‘le Hardi’ sought to take over the royal government itself, and was kept in check only by a rival contender for power – Duke Louis of Orléans. For several years France tottered on the brink of armed conflict, a prey to the rival factions. When Philip ‘le Hardi’ died, he was succeeded as duke of Burgundy and head of the Burgundian faction by his son, Jean the Fearless. The fearless new duke quickly had his rival Orléans assassinated (1407), which pushed France into a murderous civil war.

For a time, Duke Jean gained control of Paris and of the government, but the main beneficiary of the conflict was King Henry V of England. He had his own family claims to the French crown, and utilized the Burgundy–Orléanist war to invade the kingdom. He annihilated the largely Orléanist army that opposed him at Agincourt (1415), and then set about slowly conquering the forts and cities of Normandy. The English invasion hardly interrupted the French civil war, now waged between the duke of Burgundy on one side, and the young French crown prince, the Dauphine Charles, on the other. Only when Henry conquered Rouen, the capital of Normandy (1419), did the rival parties agree to come to terms. Duke Jean and the Dauphine Charles met for a peace conference on the bridge of Montereau, in order to arrange a permanent peace between themselves – and a common war against England. However, the peace conference turned ugly. Either in the heat of the moment or due to a premeditated plot, one of the Dauphine’s followers split Duke Jean’s head with a battle-axe.

Jean was succeeded by his son, Duke Philip the Good. Philip at first made a firm alliance with the English invaders to avenge his father. It was later quipped that the English entered France through the hole in Duke Jean’s head. With Burgundian help, the English gained momentary control of Paris and large parts of northern France, and for a time seemed poised to unite France and England under Plantagenet rule. However, the premature death of Henry V, the meteoric career of Jeanne d’Arc, and Burgundian defection in 1435 decided otherwise.

In fact, already long before 1435 Philip the Good turned his attention away from the Anglo-French conflict. He offered only limited assistance to the English, and after switching sides, offered even more limited assistance to the French. Instead of becoming embroiled in French politics like his father, Philip preferred to follow the less risky path of his grandfather. While the French monarchy was busy fighting for its survival, Philip sought to create a Burgundian empire in the Low Countries by picking the inheritances of dying dynasties.

His first prey was the County of Namur. Its count, Jean III, had no children, and Philip convinced him in 1420 to name him as his heir in exchange for a huge sum of money. Jean died in 1429, and Philip duly became the new count of Namur. Next came the Duchy of Brabant. In 1427 Brabant belonged to a youthful cousin of Philip the Good, called Philip of Saint-Pol. He too agreed to name Philip as his provisional heir, provided he did not have children of his own. Shortly thereafter, Philip of Saint-Pol asked for the hand of a princess of the House of Anjou, enemies of the House of Burgundy. However, he died before marrying his intended bride, on 4 August 1430, and Brabant passed into Burgundian hands. Malicious tongues whispered that the duke of Burgundy had Philip of Saint-Pol murdered.

The acquisition of Namur and Brabant paled in comparison to Philip’s next conquest. Throughout the 1420s the flourishing territories of Holland, Zeeland, and Hainault were disputed between another of Philip the Good’s cousins – the young Duchess Jacqueline – and his uncle, John of Bavaria. John spent most of his life in church service, and had no children. On 6 April 1424 Philip convinced John to name him as his heir, agreeing in return to help him in his war against Jacqueline. Exactly nine months later John died; murdered, said many, by his impatient nephew – or perhaps by Jacqueline. One of the suspected agents even confessed under torture that a poisoned prayer-book was used to eliminate the ex-bishop.1

Philip the Good now proclaimed himself John of Bavaria’s heir, and stepped up the war with Jacqueline. The unlucky duchess, who tried to establish her headquarters at the city of Mons, was betrayed by the citizens. They delivered her to Philip the Good on 13 June 1425 in order to save their city from siege and assault. Philip placed her under house arrest in Ghent, and set himself up as her guardian.2 It was not the last time that the dukes of Burgundy would lock a princess in a tower in order to get possession of her lands.

Yet victory slipped from between the duke’s fingers. In early September, when she learned that Philip was about to move her to the more secure castle of Lille, Jacqueline resolved to escape. She disguised herself in men’s clothing, and while her guards were eating, she escaped from the house together with two companions. She slipped out of the city unnoticed and rode to Antwerp still disguised as a man. There she felt safe enough to declare her true identity, and made her way to Holland, which still supported her cause. The war of inheritance, which seemed to be over, flared up again with even greater intensity.3 It took three more years of intense military efforts to defeat Jacqueline’s adherents. In 1428 she was forced to surrender. By then the young duchess had had two disastrous marriages, but no children. In the treaty of peace she agreed to recognize her cousin, Philip the Good, as her provisional heir and guardian. It was also stipulated that she could not marry again except with Philip’s approval. If she broke this term, she would forfeit her lands, which would immediately revert to Philip, who had very little intention of endangering his inheritance by allowing Jacqueline to marry. When in 1433 he discovered that she had secretly married Frank van Borselen, he kidnapped and imprisoned the unlucky husband, and forced her to renounce all her rights.

According to Monstrelet, the aggrieved Jacqueline and her mother, Margaret of Hainault, tried to avenge themselves on Philip by having him assassinated. One of Margaret’s household knights, Gille de Postelles, conspired with several other Hainault noblemen to surprise the duke of Burgundy while he was hunting in the woods. However, the plot was discovered, and Postelles and his accomplices were captured and executed.4

Shortly afterwards Philip made his peace with King Charles VII of France at Arras (1435). In exchange for abandoning the English alliance, Charles gave Philip in mortgage the Somme towns – a strategically and economically important belt of towns on France’s northern border. Philip, however, was reluctant to wage war on his former friends for the sake of his father’s murderer, and with the exception of a few noisy demonstrations, continued to focus his efforts on the Low Countries.

There another childless relative had meanwhile entered Philip’s sights. This was Elizabeth of Görlitz, duchess of Luxembourg, who had first married Philip’s uncle Anthony, and after his death married John of Bavaria, but without bearing any living children. Philip pestered his ageing aunt for two decades until she finally agreed to name him as her heir, in exchange for a yearly stipend of 7,000 florins (1441).

There were, as usual in such cases, other claimants to the inheritance. Duke William of Saxony, who enjoyed the support of many Luxembourgers, occupied the duchy and garrisoned its main strongpoints. After two years of desultory skirmishes, a Burgundian army invaded Luxembourg in 1443 to dislodge the Saxon. The countryside was easily overrun, but the two chief strongholds of Thionville and Luxembourg seemed to be beyond the invaders’ reach. Two experienced Burgundian eschelleurs named Robert de Bersat and Johannes de Montagu, accompanied by a German interpreter, were sent to infiltrate the two cities and see whether they could spot any weakness in the defences. They first infiltrated Thionville, but found nothing of use. They then infiltrated Luxembourg, climbing over the walls by means of a silk ladder, and disguised in German robes. This time Montagu discovered a hidden postern that was used by the townspeople in peacetime and was now barred. After carefully reconnoitring the postern gate and its surroundings, Montagu concluded that it could be captured with relative ease by a sudden onslaught.

On one of the darkest nights of the year, 21/2 November 1443, the walls of Luxembourg were approached by a Burgundian force of about 200 men, guided by Montagu the eschelleur and a number of local guides. Half a league away from the city they dismounted from their horses and proceeded the rest of the way on foot. They reached their destination without being detected at about 2 o’clock in the morning. A scaling party of between sixty and eighty men threw their ladders against the walls and climbed up. Montagu led the way, followed by a few other notable warriors and six archers of Duke Philip’s personal bodyguard, who carried with them a huge pair of iron pincers. Once the advance party mounted the wall they dispatched the few guards they encountered, and ran towards the postern gate, capturing it without difficulty and breaking it open using the pincers.

The rest of the Burgundian force now entered the city. They raised the war cry, shouting ‘Our Lady, the town is taken! Burgundy! Burgundy!’ The defenders woke up in alarm, and showed almost no resistance. Some fled from the city; the rest locked themselves up in the citadel. The capital of Luxembourg fell with hardly a blow being struck or a Burgundian soldier being injured. The citadel surrendered after a few weeks. The Saxon duke, disheartened by the defeat, sued for peace and agreed to evacuate Thionville too and sell Philip all his claims to the duchy for a handsome sum.5 Another claimant to the duchy subsequently appeared in 1457, in the shape of King Ladislas of Bohemia. However, just as the seventeen-year-old Ladislas began pressing his claims in earnest, he suddenly died. This time we can safely discount the rumours that he too was poisoned by Burgundian agents, though enemies closer to home may have had a hand in his death.

Luxembourg was Philip’s last major acquisition. Thanks to the barrenness of his relatives and neighbours, and thanks to the English invasion of France, which occupied the attention and resources of the king of France, the House of Burgundy now controlled not only the Duchy of Burgundy, but also a patchwork of territories covering the greater part of modern Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg, together with sizeable chunks of northern France and western Germany. Since the English were by 1453 expelled from all their Continental possessions save Calais, Philip could expect a showdown with a resurgent and vengeful king of France. Yet he was ready for that eventuality as well. With the Hundred Years War over, the duke of Burgundy was not the only French nobleman fearful of a resurgent French monarchy. In the 1450s and 1460s a coalition of territorial French princes gathered around the Valois duke of Burgundy, all anxious to curb the power of the French king.

The stage was thereby set for a collision between the two branches of the House of Valois. The senior branch, now headed by a new king, Louis XI, aimed to reunite France and transform it into a centralized kingdom. The cadet Burgundian branch aimed both to keep France a motley collection of autonomous principalities, and simultaneously to fuse its own disparate dominions into a centralized polity.

However, Burgundy had for some time been facing an enemy far worse than the king of France. The same type of genealogic calamity that had been so far the fountain of its power was now threatening the House of Burgundy itself with extinction. Philip the Good had several sisters, but no brothers. His father sought to safeguard the family inheritance by marrying Philip off at the relatively tender age of thirteen (1409). However, the chosen wife, Michelle of France, failed to provide Philip with any children before she died in 1422. She was poisoned, some believed, by one of her ladies-in-waiting.6 Philip quickly remarried, taking as his wife one of his many aunts, Countess Bonne of Nevers. She died in 1425, leaving to Philip the County of Nevers, but no heirs.

In 1430 Philip married again, this time Princess Isabel of Portugal, who bore him a son in 1431, and another in 1432, but both died in infancy. By this time Philip had already sired an entire troop of bastards – as many as twenty-six are recorded.7 Yet none of these could succeed to the family fortune. Another legitimate son was born in 1433, and was christened Charles. After him, Isabel bore no more children.

Charles, who at birth was made count of Charolais, survived the dangerous years of infancy. His birth had momentarily brightened the family prospects, but they remained precarious. If he died, or failed to produce legitimate offspring of his own, the family inheritance was likely to break up between a host of distant relatives, foremost among whom were the Valois kings of France. To ensure the succession, Philip married off Charles when he was a child of five. However, the chosen bride died in 1446, and the question of succession remained as open as ever. Charles was again married, to his cousin Isabel of Bourbon, who lived until 1465, but bore Charles only one child, Marie. This daughter, born in 1457, was Charles’s sole heir and the richest prize in the European marriage market. With her the story of Valois Burgundy came full circle. It began with a rich heiress, and now it seemed destined to end with one.

From 1457 the question of the Burgundian inheritance came to dominate European dynastic politics. Could Marie – a woman – inherit the vast Burgundian patrimony? This was far from certain, at least regarding the Burgundian dominions within the Kingdom of France. And even if Marie could inherit her father’s empire, who would marry her and add that empire to his own patrimony?

Since Marie’s rights of inheritance were doubtful, Charles ought to have married her off as soon as possible, in order to establish her husband and children in place, and secure their position before his own death.8 But he failed to do so. During his reign he arranged for Marie numerous marriage alliances, and broke them all one after the other. His behaviour resulted partly from a psychological reluctance to give up control of his daughter and set up a foreign man as his heir. But partly, she was just too valuable for him as a diplomatic pawn. He repeatedly gained allies by promising them her hand, and almost as often broke up hostile combinations by promising her to one of his would-be enemies. These short-term advantages, however, greatly exacerbated Charles’s long-term position. For as long as Marie remained without husband and children, the future of the Burgundian inheritance continued to be in doubt.

Hence from the moment of his birth till his dying day, Charles knew that the fate of his house and of the burgeoning Burgundian state depended solely on his own life. The numerous conquests his father had made were poignant reminders of the fate installed for Burgundy in case Charles died without a legitimate male heir. The numerous true and false stories of poisoning and assassination that circulated around the Burgundian court were equally poignant reminders of the precariousness of his life. In particular, the fate of his grandfather at Montereau was never far from people’s minds in the ducal court. During Charles’s childhood, more anxiety was added by the rising reputation of George de la Trémoille as a master of dirty warfare. La Trémoille was the power behind King Charles VII for much of the 1420s and 1430s. In 1427 he arranged the murder of Charles VII’s previous two favourites, the Lords of Giac and of Beaulieu, and was later credited with the kidnapping, assassination, and attempted assassinations of other rivals and enemies. In 1432 he plotted to kidnap the Burgundian chancellor, Nicolas Rolin, from deep within Burgundian territory. Rolin had two lucky escapes in 1432 and 1433, following which he was allowed to keep about him a personal bodyguard of twenty-four archers. Duke Philip the Good himself raised his own personal bodyguard from twelve archers to twenty-four. In 1438 he increased their number again to fifty.9

As Charles grew up, the close ties he established with Italy and his suit of Italian courtiers could only have exacerbated his home-grown fears. For Italy had a reputation as a land of assassins and poisoners, and every year news of fresh assassinations or assassination plots streamed north from the glittering and turbulent courts of the peninsula. The news from the British Isles were hardly more assuring. The uncouth islanders lacked the Italians’ finesse in the use of poison and dagger, but throughout the fifteenth century the royal and noble clans of both England and Scotland devastated one another with barbarous ferocity. At least three kings and two crown princes, as well as numerous dukes and earls, were imprisoned and murdered during those violent decades.

Charles’s mother, Isabel of Portugal, added to the fearful atmosphere. She was, according to her husband’s testimony, ‘the most apprehensive lady he had ever known’ 10 Not surprisingly, her son too was a rather paranoid prince.

Charles became fearful of assassination plots already before he became duke. In the late 1450s and early 1460s his position in the ducal court was uneasy. His father was gradually sinking into senile atrophy, and several factions fought for control of the old man and of the Burgundian government. Charles was a defiant son and an incompetent courtier, and his relations with his father gradually deteriorated. The old duke deprived his heir of any share in the Burgundian government, and instead relied more and more on the powerful noble clan of the Croys, who for a time became virtual rulers of Burgundy.

A deep hostility naturally developed between Charles and the Croys, whom Charles feared might become de facto regents of Burgundy. He also suspected them of plotting with King Louis XI of France his own elimination. The Croys had been receiving French bribes on a regular basis since 1435, and if they were not downright traitors, they were certainly of mixed loyalty. As long as Duke Philip lived, their chief loyalty was still to him, particularly since through their control of the old duke they amassed more and more lands and riches in Burgundy. Yet it was obvious to them that sooner or later Philip would die, and if Charles then succeeded as duke, the day of reckoning could be extremely harsh.

In July 1462 Charles accused Jehan Coustain, one of the Croys’ protégés at the ducal court, of attempting to poison him. He had Coustain apprehended in Brussels, then brought him to the castle of Rupelmonde and quickly executed him before either the Croys or Duke Philip could intervene. Contemporary chroniclers made much of the juicy story Charles spread about, but it is impossible to say how much truth it contained. Perhaps the Croys really intended to get rid of him, then govern Burgundy in the name of Philip the Good and his infant granddaughter, whom they could marry off as they pleased. Perhaps Coustain and the Croys were innocent, and Charles concocted the whole story to incriminate them and regain favour with his father. Perhaps the Croys were indeed innocent, yet the fearful and disgruntled Charles actually believed that they were plotting his elimination. At the very least, the Coustain affair heightened the tension in the Burgundian court, and raised the question of assassination in unequivocal terms.11 A year later, Charles accused another rival at court, the count of Étampes, of making wax images of him in order to cast spells on him.

The Coustain affair failed to improve Charles’s standing with his father. Philip did not believe his son’s story and continued to put his trust in the Croys. In fact, the Croy family now reached the apogee of its power, and succeeded in securing a major coup for King Louis. When King Charles VII gave Philip the Good the Somme towns in order to buy his alliance (1435), it was stipulated in the treaty that the kings of France could redeem these towns for a large sum of money. Charles VII never managed to do so. One of Louis’s first aims upon succeeding his father was to regain this vital area. In 1463 the Croys convinced Philip to agree to sell the towns back to the king of France, despite Count Charles’s vehement protests. The deal led to another major crisis between father and son, and manifested the power of the Croy family. Charles was reportedly haunted now by fears that the Croys would apprehend and imprison him.12 He distanced himself from the court, and attempted to build up an independent power base in Holland, in case his father might completely disinherit him.

Shortly after gaining the Somme towns, Louis came up with another suggestion. Anxious to exploit to the full the hold he had over Philip through the Croys, Louis offered to buy from Philip the towns of Lille, Douai, and Orchies. These towns also possessed great economic and strategic importance, yet unlike the Somme towns, they were an old Burgundian territory, part and parcel of Margaret de Mâle’s dowry. Louis argued that these particular towns were given a long time previously by the kings of France to the counts of Flanders and their male heirs, but they could not be inherited by or through a woman. The Croys pressured Philip to sell the towns and avoid war, and Philip met Louis several times at Hesdin to discuss the offer, as well as several other outstanding issues. Charles fiercely objected to this new venture, rightly depicting the Croys’ stance as treasonous. However, his opinions carried little weight. While Philip and the Croys were at Hesdin negotiating with King Louis, Charles was left to sulk in his castle of Gorinchem, in Holland, which stood about 40 kilometres east of Rotterdam, on the river Merwede.

At this moment, an even more serious scandal than the Coustain affair exploded. Louis XI had in his service a shady character, the Bastard of Rubempré, who was reputed to be ‘a courageous and enterprising man’,13 but was also known as ‘a man of ill-repute, a murderer and a bad lad’,14 and as ‘a man of an evil name, of light counsel, and of bad doings’ 15 The Bastard was also a nephew of the Croys. In September 1464 he was given secret instruction by Louis to undertake a delicate mission deep within Burgundian territory. He gathered a band of forty to eighty cut-throats, hired a light corsair vessel at the port of Crotoy, and sailed northwards. ‘None of the crew,’ says the chronicle of Wavrin, ‘knew whither the bastard intended to carry them, nor what orders he was charged with, except that they were told they must follow him wherever he should choose to lead them, and do anything he commanded them.’16

Rubempré’s ship arrived at Armuyden on the coast of Zeeland sometime in the middle of September. Rubempré left his ship at anchor there, took with him a few of his most trusted companions, and together they made their way on foot inland, towards the town of Gorinchem. Once they reached the town, they took up lodging in the best hotel, pretending to be merchants on business. They stayed there for three weeks, according to the chronicle of the Hague, and began making inquiries about Charles’s habits and household arrangements: When did he use to go out to sea? In which kind of ship did he usually sail? When did he go hunting? Did he go about with a large or a small company? Did he go in the morning or in the evening? Rubempré then made a reconnaissance of the castle and its environs, climbing the walls and examining with particular interest the route back to the sea-coast.

Though the courts of princes always attracted many hangers-on eager for information about their activities, Rubempré’s inquiries aroused suspicions. According to the chronicle of the Hague, it was the hostess of their hotel who became suspicious of her guests and reported them to the authorities. According to Chastellain, Rubempré had served Charles in the past, and was now recognized by some of Charles’s household members. His activities were reported to the count, and when Rubempré heard of it, he became frightened and took shelter in a church, from where he was taken and thrown into prison. According to another version, it was not Rubempré but rather one of his companions who was recognized in an alehouse and asked about his business. The man said that he was part of an armed force under the command of the Bastard of Rubempré, sent to Holland by the king of France. What their mission was, however, he did not know. The report alarmed Charles, who immediately sent men to apprehend Rubempré, and another force to capture the ship.

In prison Rubempré at first claimed that he was a merchant on his way to Scotland. He then changed his story and said he was actually going to visit the Lady de Montfort, daughter of the lord of Croy. Yet soon enough he broke and confessed everything. What he confessed, though, remained a closely guarded secret. This did not prevent rumours from spreading, probably with active encouragement from Count Charles. Rubempré, it was reported in alehouses, churches, and palaces throughout the Low Countries and France, was sent to Holland by King Louis in order to kidnap Charles and bring him to France. Some added knowingly that if Rubempré failed to kidnap the count, he was instructed to kill him instead.

Thomas Basin, a source extremely hostile to Louis XI, writes that Rubempré confessed in front of numerous trustworthy persons, and without being subjected to any torture, that he meant to kidnap Charles on one of his excursions, take him to the ship, and bring him to Louis either alive or dead. Once Charles was imprisoned or killed, some of the reports continued, Louis intended to sweep down on Duke Philip at Hesdin and secure his person too. He would then marry off Marie of Burgundy to whomever he liked, and carve up the Burgundian inheritance as he pleased.

The chronicle of the Hague gives the most detailed explanation how Rubempré supposedly planned to kidnap Count Charles. The Bastard’s ship was of a unique design, and its master mariner promised Rubempré that he could take him to Holland and back safely even if all the fleets of England and Holland tried to block his way. Charles was extremely fond of the sea and of sailing. His intimate friend Olivier de la Marche confirms that ‘more than anything, he had a natural love of the sea and ships’ 17 Rubempré therefore believed that if he spread word in Gorinchem of his wonderful ship, Charles would become curious and come to inspect it in person. Once the count boarded ship, Rubempré’s men could overpower his guards and carry him away. Alternatively, Charles could be ambushed on one of his frequent excursions to the coast and the sea, and taken on board forcefully. The chronicle further says that when Rubempré was captured, a letter was found on him sealed with the private seal of Louis XI, in which the king promised Rubempré great rewards if he brought him Count Charles. The last detail, however, casts doubts on the veracity of this report. Rubempré would have been crazy to carry on his person such incriminating evidence.18

As soon as Rubempré was taken and questioned, Charles sent to Hesdin the commander of his bodyguard, Olivier de la Marche, to beat the wave of rumours and inform Duke Philip of the affair in carefully chosen words. La Marche arrived at Hesdin on 7 October, while Philip was taking his midday meal. He apparently told the duke that Count Charles had barely been saved from a kidnapping attempt, and that Philip too might be in danger. According to a letter sent to Duke Francesco Sforza of Milan, La Marche also brought with him a written copy of Rubempré’s interrogation, in which the Bastard confessed that he was ordered by the king of France to take with him about eighty people and kidnap Count Charles.

Philip became alarmed. Though he had discounted his son’s allegations during the Coustain affair, there were enough reasons to suspect King Louis. Not least of these was the fate of Philip, the younger son of the duke of Savoy. King Louis had always shown great interests in the affairs of Savoy, the Alpine duchy bordering France and Burgundy to the south-east, which controlled the vital mountain passes connecting Italy and north-western Europe. He had even taken one of the duke of Savoy’s daughters as his wife, whereas his sister Yolanda was married to the Savoyard crown prince, Amadeus. Philip of Savoy was leader of the anti-French faction in Savoy, and strongly objected to French intervention in Savoyard politics. A few months before the Rubempré affair, Louis had invited Philip to visit his court and settle their differences, providing him with all the necessary promises and safe-conduct letters. Yet once the Savoyard prince arrived, Louis broke his word and imprisoned him in the dreary fortress of Loches. Such dishonourable conduct aroused outcries throughout the courts of Europe, but Louis did not yield.

The duke of Savoy was Philip the Good’s cousin, and Philip of Savoy was actually named in honour of the Burgundian duke. In August 1464 the sorrowful duke of Savoy paid Hesdin a visit, and for twenty-five days implored the duke of Burgundy to intervene with King Louis and set his son free. The issue was raised during Philip’s meetings with Louis, but nothing came out of it. In early September, the disappointed duke of Savoy left Hesdin. Philip of Savoy continued to languish in Loches for two more years, where he composed a mournful chanson about the treason of the king of France. Could the news from Holland mean that King Louis was trying to betray the house of Burgundy in a similar fashion?19

Chastellain says that people at Philip’s court also began to talk of the bridge of Montereau and other past French treacheries. Suspicions were fuelled by the circumstance that, shortly before La Marche’s arrival, Duke Philip had received a message from Louis, saying that he was on his way to Hesdin, and intended to visit Philip the following day. Louis was reportedly accompanied by a strong guard, whereas Philip had only a small force at Hesdin. After a short deliberation, Philip decided to take no chances. He hardly waited to finish his meal, and hastily departed Hesdin with only six or eight horsemen, letting as few people as possible know of his departure. He first made his way to Saint-Pol, about 20 kilometres away, which he reached by nightfall. Early next morning he continued on his way, reaching Lille, deep within Burgundian territory and far from the menacing king of France, by 10 October.

Louis was disappointed to hear of Philip’s sudden departure. Not knowing what prompted the move, he made his way back to Abbeville, and from there to Rouen. So far, he had heard nothing from or about Rubempré. But within days news began to stream in. Everywhere it was said that King Louis had sent the Bastard of Rubempré to Holland in order to kidnap or assassinate the count of Charolais. Louis was flabbergasted. This was a political and diplomatic disaster of the first order. He responded quickly, sending messengers far and wide to spread his own version of events. Yes, he had sent Rubempré with fifty men to Holland. And yes, they were ordered to kidnap an important personality there. But their target was not Count Charles of Charolais; rather it was Jehan de Renneville, the vice-chancellor of the Duchy of Brittany.

Brittany, like Burgundy, was a French duchy in theory and an independent principality in practice. The dukes of Brittany had never really accepted the authority of the king of France, and for much of the preceding century had allied themselves with his enemies. In the 1420s it was a triple alliance of Brittany, Burgundy, and England that came close to eliminating the king of France. After Louis XI acceded to the throne the fearful duke of Brittany tried to revive that alliance. He had therefore sent his vice-chancellor on an embassy to England to conclude a treaty. From there he was instructed to proceed to Holland, meet the Burgundian heir apparent, and induce him to join the alliance. Louis XI, who was closely informed of events in Brittany by a network of spies, heard of Renneville’s mission, and had sent Rubempré to Holland to kidnap Renneville before he could meet Count Charles. By such means Louis hoped to foil or delay the formation of the alliance, and also to be intimately informed of its proposed details.

Louis protested that since the duke of Brittany was technically his vassal, such kidnapping was really just a legal arrest of one of his own subjects. He also vehemently emphasized that he never had the slightest intention of kidnapping Charles or harming him in any other way. It was solely due to his own excessive fearfulness that Charles suspected Rubempré and had him apprehended. To strengthen his point, Louis added that it would have been quite impossible to kidnap Charles using only fifty men, and that if he really wanted to do so, he would not have entrusted the job to the riff-raff pirates of Picardy.

Was Louis telling the truth or trying to extricate himself by means of an ingenious lie? As usual in such cases, the truth cannot be known for sure after half a millennium. All details of the Rubempré affair were quickly buried beneath a mountain of propaganda, for the case developed into a major political and diplomatic crisis with far-reaching consequences. Count Charles recognized that this was his best chance to regain his father’s favour and undermine the influence of Louis and the Croys in the Burgundian court. Louis on his side was frantic to defend his good name, save the Croys, and prevent an open rupture with Burgundy.

Assuming that the best defence was a vigorous attack, Louis quickly went from confessions to accusations. Laying aside the fact that even by his own admission he had sent a gang of pirates into a friendly country in order to kidnap a senior diplomatic emissary, he began acting as if he was the wronged party. Within days of hearing the news from Holland, he sent an express and aggrieved message to Duke Philip. He was surprised and dismayed, he said, that Duke Philip departed so suddenly from Hesdin without waiting to meet him. He had furthermore heard that some preachers in Bruges were spreading rumours that he had intended to kidnap or murder Count Charles. He was extremely angry about this libel, and expected the duke of Burgundy to quash these rumours immediately and punish those guilty of spreading them.

Shortly afterwards, another demand was forwarded to the duke of Burgundy. King Louis wrote that he had now heard that the real culprit was not some anonymous Bruges preachers, but rather Olivier de la Marche. It was he who brought about the capture of Rubempré;20 it was he who subsequently brought Duke Philip the first news of Rubempré’s arrest; and it was he who wrongfully told the duke that the Bastard intended to kidnap Charles. Moreover, Louis asserted, while riding from Holland to Hesdin, La Marche did not keep his mouth shut, but spread the same false rumours far and wide. The king demanded that Philip turn over to him both the Bruges preachers and La Marche. Finally, Louis wrote to Philip that he would like to have Rubempré himself back.

By making such demands, Louis put Charles in a tight corner, and forced a power struggle within the Burgundian court. If the Burgundians handed over La Marche, it would have meant that Charles invented the whole thing, and was either a liar or a fool. Even worse, it would have shown that the count of Charolais was incapable of defending even his staunchest and closest servants. His honour and his position in Burgundy and abroad would have suffered a fatal blow.

To decide the issue, Charles, the Croys, and the ambassadors of the king of France came before Duke Philip at Lille, on 4/5 November 1464. The ambassadors restated the French version of events, and demanded that Rubempré, the Bruges preachers, and La Marche be handed to them. Charles then fell on his knees, and remonstrated with his ageing father. According to an unpublished chronicle, Charles argued that Louis’s version of events made little sense. If Rubempré intended to intercept the Breton vice-chancellor on his way from England, why did he leave his ship anchoring on the Zeeland coast, and make his way to Gorinchem, which is perhaps 60 kilometres inland? Moreover, if he was a royal French agent employed on the lawful mission of arresting a traitor, why was it that when he reached Gorinchem, he did not present himself before the count of Charolais, as normal etiquette demanded?

The latter argument was obviously disingenuous, but the former certainly made sense. Charles carried the day. Philip was either convinced that Charles’s story was true, or at last realized where his true interests lay. Regardless of whether Charles was telling the truth or not, Philip owed his loyalty and support to his son and heir rather than to the Croys and Louis. Philip answered all of Louis’s demands in the negative. He had no intention of handing back Rubempré: that pirate had been arrested in Holland, where Philip was sovereign and recognized no lord save God, and he would be judged there according to his merits and crimes.21 As for the Bruges preachers, Philip excused himself that he was a secular prince and refrained from intervening with the clergy. Moreover, he explained to Louis, ‘many preachers are not very wise, and they quickly say things without advice and without authority.’22 Finally, regarding La Marche, to the best of Philip’s knowledge, he had done and said nothing wrong.

The French ambassadors left in dismay. Making their way back to King Louis, they passed through Tournai, Douai, Arras, Amiens, and several other important French towns. In each place they convened the town’s estates, formally repudiating the ugly rumours spread about Louis and swearing on the honour of the king that he did not attempt to kidnap Charles. If anyone repeated these rumours again, they were to be arrested and sent to the king, to face his wrath and justice.23

The Rubempré affair thus ended as a decisive victory for Charles. Either he or the Breton ambassador were saved from Louis’s clutches. The king’s honour suffered a severe blow both within and outside his domains. Most importantly, from November 1464 onwards Charles and Philip were reconciled; the Croys lost their grip on the Burgundian court; and Charles became the real power there instead. Within months the Croys were fugitives in France, while Charles launched a war against Louis XI in alliance with the duke of Brittany and several other leading French princes, which came within a hair’s breadth of toppling Louis and fragmenting the kingdom of France.

· · ·

THE war which Charles and his fellow princes launched against King Louis XI in 1465, commonly known as the War of the Public Weal, involved various special operations. For example, on the night of 3/4 October 1465 a Burgundian raiding party captured by escalade the town of Péronne together with its lord, the voodoo-practising count of Étampes. The only interesting incident in terms of assassination attempts, however, took place shortly after the battle of Montlhéry.

When the Burgundian army joined its allies at Étampes after this battle, the soldiers of both armies enjoyed themselves in the streets while Count Charles of Charolais and Prince Charles of France – the rebellious brother of King Louis XI – conferred in one of the town’s houses. As the two commanders were ‘at a window, talking to each other very intimately’, a poor Breton soldier called John Boutefeu was amusing himself at the expense of his comrades. He stood in a house overlooking the street, and threw firecrackers at the soldiers who passed below. One such firecracker accidentally fell against the window frame where the princes were conferring, and both were startled, thinking it was an assassination attempt. They immediately gave orders to arm their bodyguards and other household troops. Within minutes, two to three hundred men-at-arms and archers surrounded the house and mounted a search to find the would-be assassin. The trickster eventually confessed and was forgiven, and all ended well.24

This incident shows how edgy the princes were. Curiously though, it also shows how flimsy their security measures were. Nobody prevented the Breton soldier from approaching the princely residence with a load of explosives, and a guard was mounted at the entrance only after the firecracker exploded. Perhaps in the mayhem that followed the battle of Montlhéry, normal procedures were momentarily suspended. Then again, perhaps the security measures taken by Olivier de la Marche – the commander of Charles’s bodyguard – were simply inadequate. No wonder that La Marche does not mention the incident in his memoirs.

The War of the Public Weal ended as a qualified Burgundian victory. The power of Louis XI was curbed, and he was even forced to return the Somme towns to Burgundy. For the next couple of years Louis was put on the defensive, whereas Charles grew strong. He became duke of Burgundy upon the death of his father in 1467. He was also the leader of a formidable, albeit fragile, alliance of French princes whose goal was to keep Louis XI in check. In 1468 Charles married for a third time. Whereas his first two wives were French princesses, he now wed Margaret of York, sister of King Edward IV of England. She bore him no children, but greatly strengthened Burgundy’s relations with England.

Louis XI, already fearful of Charles’s rising power, was now alarmed by the spectre of an Anglo-Burgundian alliance. When hostilities between Louis and the French princes were renewed in 1468 Louis decided that he had better meet the new duke of Burgundy in person and settle their differences. Given the precedent of Montereau and Charles’s past fears of assassination and kidnapping, Louis took a bold step. He told Charles he was willing to come to visit him in the Burgundian town of Péronne, accompanied by only a few of his men. Charles agreed. And thus the fox entered the wolf’s den, of his own free will, trusting solely in his cleverness. Louis brought with him into Péronne only fifty men, whereas Charles firmly controlled the town and had an army of several thousand men camped nearby. It was 9 October 1468, exactly four years since Rubempré had been caught.

What followed has been described and analysed numerous times. Charles, always suspicious of Louis, had hardly received the king of France into the castle of Péronne when he heard news that the city of Liège had attacked his rear. Liège, one of the most powerful and turbulent cities of the Low Countries, had been a pain in Burgundy’s side for decades, and in 1465 it rebelled against its prince-bishop, Louis of Bourbon, who was an ally and relative of the Burgundian duke. The duke of Burgundy came to the bishop’s aid, and had to mount three successive expeditions against the rebels until he finally defeated them in battle, destroyed their city’s fortifications, and forced the rebel leaders to flee into exile.

In September 1468, when King Louis saw that another confrontation with Burgundy was imminent, he encouraged the Liégeois to rebel again. With his encouragement, the exiles returned to Liège on 9 September, massacred their opponents and prepared for war. Duke Charles took the news lightly. He continued to concentrate most of his forces against France, and dispatched towards Liège only a small army, several thousand men strong, assuming that it would not be too difficult to crush the new rebellion.

While King Louis was asking Charles to meet him for a peace conference, he continued to send agents to Liège, promising his aid to the rebels and inciting them to attack their prince-bishop and his Burgundian allies. When Charles agreed to meet Louis at Péronne, Louis did not know what fruits his agents’ efforts bore. To wait until he had sent new agents to Liège to countermand his previous moves and urge peace on the Liégeois would have taken far too long. He hoped the Liégeois had not had time to undertake any major operations, and confidently rode to Péronne.

Unfortunately for Louis, the Liégeois had taken his bait, and had moved with unusual celerity and boldness. On the night of 9/10 October a small raiding party left Liège under command of Jehan de Wilde and Gossuin de Streel and headed towards Tongres, the headquarters of the prince-bishop and his Burgundian army. The Burgundians were taken completely by surprise. They believed that Liège was defenceless and that its sole hope lay in receiving French assistance. On the evening of the 9th they heard of Louis’s arrival at Péronne, and concluded that no French help would be forthcoming and that Liège was consequently doomed. When the raiders arrived at Tongres a few hours later, in the middle of the night, the surprised Burgundians offered no resistance. The entire army collapsed and fled in panic. The Liégeois did not bother to pursue the fugitives, but they did capture Bishop Louis and carried him back in triumph to Liège. During the march back the burghers killed several of the bishop’s servants and councillors. Reportedly, they amused themselves by cutting the hated Archdeacon of Liège Cathedral, Robert de Morialme, into small pieces, and throwing them at one another’s heads.

The townsmen now hoped to reach a separate peace agreement with their captive bishop, thereby making any further Burgundian intervention redundant. According to several medieval and modern authorities, the prince-bishop himself by this time may have been quite happy to strike an independent deal with Liège, realizing that a peace agreement dictated by the duke of Burgundy would reduce him to a powerless puppet.

News of this disaster reached Charles at Péronne on the evening of 11 October. The first reports stated that the Burgundian army was destroyed, that the bishop of Liège was murdered, and that royal French agents were seen amongst the attacking forces. Though Charles knew of Louis’s dealing with the Liégeois before, he had previously discounted them as insignificant. Now defeat stung his pride and rekindled his deepest suspicions. In 1419 Louis’s father had ostensibly come to Montereau to talk peace with Charles’s grandfather, but in fact had him assassinated. In 1464 Louis himself was talking peace with Duke Philip at Hesdin while sending Rubempré to Holland to kidnap or kill Charles. Now in 1468 Louis had come to talk peace with Charles at Péronne, while inciting the Liégeois to kidnap or kill their bishop. Charles worked himself up into an overpowering rage. He was going once and for all to pay the French monarch for his treacheries. In addition, Charles perhaps could not resist the temptation to inflict upon his chief enemy the fears that haunted him for years.

The gates of Péronne were shut tight, and armed guards were placed around Louis’s quarters. He was not formally imprisoned, but he was constantly watched. Not a person dared speak with the king except by loud voice, to assuage any suspicions that he was planning a secret breakout. Some chroniclers state that Charles contemplated killing Louis there and then, and crowning Louis’s weak brother in his stead. For several days the king lived in fear of this possibility. He was made apprehensive by the presence of several of his mortal enemies around Charles, most notably Philip of Savoy, who had only recently been set free from Loches. Louis was hardly comforted when Charles reminded him that a king of France had previously been held prisoner in the castle of Péronne. This was King Charles the Simple, whom a count of Vermandois seized in 923 and held there for six years, until he expired.

Duke Charles eventually decided to spare the king, but to impose upon him the harshest possible peace conditions. These were formulated in the peace treaty of Péronne, which gave Charles anything and everything he thought of demanding from Louis. The treaty virtually secured the establishment of an independent Burgundian state, and well-nigh insured the permanent fragmentation of the Kingdom of France. The helpless Louis duly signed, but Charles realized his signature would be worth very little once he were be allowed to depart.25

In order to keep Louis in his possession for a little longer and in order to humiliate him further, Charles came up with a new demand. When news of events in Liège first reached Péronne, Louis said that in order to prove his innocence, he was willing to march along with Charles and together subdue the recalcitrant city. Now that peace was made between them, would Louis make good his promise, and join Charles for the expedition against Liège? Louis tried to wriggle out, but eventually he had little choice but to agree. Thus Charles set out for Liège carrying the king of France in his baggage. To keep up appearances, both the Burgundian duke and the French king pretended that Louis was accompanying Charles from his own free volition. Charles even allowed Louis to bring along a small French contingent, including the royal guard of 100 mercenary Scottish archers and another 300 men-at-arms. They were, however, badly treated. Ludwig von Diesbach, a Swiss page of Louis XI who accompanied him to Péronne and Liège, and who later composed an autobiography, writes that he and his companions suffered greatly from hunger and cold, and feared for their lives due to the hatred of the Burgundians around them.

When the Liégeois heard of the events at Péronne, they naturally lost heart. Unable to face Burgundy by themselves, they quickly released the prisoners they had taken at Tongres, including their prince-bishop, and pleaded for peace. But Charles would have none of that. It was the fourth campaign he was leading against Liège in three years, and he was now determined to raze the city to the ground once and for all. The desperate Liégeois mounted a few bold sorties against the advancing Burgundian steamroller, but it availed them little. On 27 October Charles, Louis, and the main Burgundian force arrived before the ruined walls of Liège. The bulk of the forces encamped to the west of the city, in front of the Sainte-Walburge Gate. Another large force was posted to the north of the city. Charles did not bother to block the eastern or southern approaches. Given the state of its fortifications and forces, he assumed that the city would easily fall to a direct assault.

Charles set up his quarters about half a kilometre from the Sainte-Walburge Gate, in one of the still standing suburban houses. Louis was lodged in a nearby house. Two days and nights of desultory skirmishes followed, during which several Liégeois sorties were repulsed, while the majority of the population fled the doomed city, and the besiegers prepared for the final assault. The assault was first set for 29 October, but it rained heavily, and Charles decided to postpone it until the following morning. As Philippe de Commynes writes, by now the Liégeois ‘had not one professional soldier in their garrison… They had neither gate, nor wall, nor fortification, nor one piece of cannon, which was good for anything.’26 The few remaining Liégeois contingents suffered heavily in the abortive sorties. Everyone in the Burgundian camp therefore expected it to be a walk-over. The soldiers went to sleep happy, dreaming of the following day’s easy conquest and of the orgy of rapine, loot, and destruction that awaited them. Since the duke planned to annihilate Liège anyhow, there would be even fewer curbs on their behaviour than usual.

The Liégeois indeed seemed to be helpless prey. However, Gossuin de Streel, commander of the raid on Tongres, came up with a desperate plan. They had brought destruction on their heads by raiding Tongres at night and capturing their bishop by surprise. Why not repeat the same performance, only this time direct it at the duke of Burgundy himself? If a few resolute souls could make their way into the Burgundian camp and kill or capture the duke, Liège might still be saved. In fact, if they managed to kill the duke, the entire Burgundian state was likely to disintegrate. Streel convinced the remaining Liégeois leadership that this was their only chance to save the city, and they decided to give it a try. They would kill Duke Charles or perish in the attempt.

Charles was surrounded by thousands of Burgundian soldiers. Strong pickets were placed in front of the ruined walls, to give advance notice of any sortie. Charles also had a permanent bodyguard of forty crack archers, under the command of Olivier de la Marche, who never budged from his person during either wartime or peacetime.27 Apparently, shifts of twelve archers took turns guarding the duke’s person around the clock, and they were now lodged in the same house as Charles, occupying the upper floor. Another complication was posed by the presence of King Louis. The king of France posted his 100 Scottish archers around his house, and the rest of his men-at-arms camped nearby. Charles feared that Louis might try to escape, or worse, might try to attack him under cover of night with this elite force. Charles therefore chose 300 of his best and most reliable men-at-arms, and posted them in a big barn that stood between the two princely dwellings. This group of men was meant primarily to safeguard Charles against a sudden onslaught by the royal French bodyguard, but it could also fall upon any force coming from Liège.

No Liégeois sortie could hope to defeat these forces in open combat. However, Streel hoped that a small and resolute force could infiltrate the Burgundian camp under cover of darkness, and reach the duke before the alarm was raised. He knew exactly where Charles and Louis slept. The houses in which they were quartered were marked with all the pomp and circumstance of princely residences, and stood but a few hundred metres from the ruined ramparts. The lie of the ground was perfectly familiar to the Liégeois. Most importantly, the previous owners of the two houses which now sheltered the duke and the king were in Liège, and they gave Streel all the information he needed about these dwellings and their immediate surroundings. One vital piece of information was that Charles’s lodging was placed near a deep and rocky ravine, called the Fond-Pirette. The ravine secured Charles against any conventional attack from his flank, but it was also an ideal conduit for secret infiltration. The two vengeful landlords further agreed to serve as guides and personally lead the strike force against their unwanted new tenants.

According to Commynes, Streel received information on 29 October that the final assault on the city was planned for 8 o’clock on the following morning, and that therefore during the coming night the duke ordered all his army and even his guards to disarm and refresh themselves. This greatly enhanced his hopes of success. Streel also hoped that the weather might work in their favour. The 29th was a stormy day, and the bad weather was likely to help conceal secret moves.

Between 200 and 600 men were detailed to undertake the strike, commanded by Vincent de Bures and Streel himself. They were not special forces in any sense, but probably contained the best of the remaining Liégeois troops. Particularly conspicuous among them was a large contingent of men from the mountainous district of Franchimont. The rest of the Liégeois forces were also put on alert. Once they heard the war cries rising from the Burgundian camp, they were to sortie out of the city and create as much havoc as possible, to confuse the Burgundians and prevent them from sending reinforcements to the one place where they could still lose the war.

Only one big question mark remained: what about King Louis? It is impossible to say what Streel and the Liégeois intended to do with him. Their chief aim was without doubt Duke Charles. Perhaps they wanted to liberate the king of France, if they could. Perhaps, as many sources indicate, they wished to kill him, in retaliation for his betrayal. Perhaps they hoped that in the dead of night, when the alarm sounded, the king would order his guards to join the attackers and help them liquidate Duke Charles.

About ten o’clock on the night of 29/30 October, Streel and his men set out from the Sainte-Marguerite Gate, which was not guarded or watched by the Burgundians. Walking in a circuitous route, they made their way cautiously towards the Fond-Pirette ravine, and were swallowed inside without being observed by any Burgundian outpost. They then slowly threaded their way amongst the rocks until they emerged from the other side of the ravine.

The Burgundian camp was silent. The duke and the king were in their lodgings, fast asleep. The information Streel received was correct, and even the guards in the nearby barn had taken off their armour a mere two hours previously, and were now resting. For the last three days and nights they had been engaged in constant skirmishing, and Charles wanted them to be fresh for the next day’s assault. The twelve archers on duty as Charles’s personal bodyguard were busy playing dice in the room above Charles’s bed. Only the Burgundian sentinels were alert. The lord of Gapannes, their commander that night, had spread a cordon of scouts and sentinels between the camp and the ruined walls, ready to sound the alarm. But neither he nor any of his men had detected the Liégeois’ flank march. Apparently, no sentinels were placed along the Fond-Pirette ravine.

The Liégeois began dribbling into the camp. The camp contained thousands of soldiers and camp-followers belonging to different units, countries, and languages, and it was in place for only the last three days. The Liégeois could therefore hope that in this Babel they would not be recognized as enemies until it was too late. Several sources affirm that to blend in more easily, the raiders sewed on their tunics the cross of St Andrew, the Burgundian badge, and when questioned, claimed to be Burgundian soldiers. They nearly reached the duke’s quarters when something went wrong. According to Commynes, who slept that night in Charles’s own room, the fault lay squarely with the Liégeois. Charles would surely have been killed, writes Commynes, except that some of the raiders prematurely attacked the nearby tent of the duke of Alençon and the fortified barn, either due to their impatience or because they mistook them for Charles’s quarters.

Jean de Haynin and Onofrio de Santa Croce say that the raiders made no such mistake, and were halted a short distance from the duke’s bed only by the alertness of some women camp-followers. Haynin writes that the raiders’ vanguard had reached the kitchen of Charles’s house without being detected. Yet just as they were about to enter the house itself, they were stopped and questioned by a washer-woman called Labesse (or perhaps nicknamed, ‘the Abbess’), who was apparently accompanied by some other female camp-followers. The raiders claimed to be Burgundian soldiers, but either Labesse or some other woman became suspicious of their accent, and said aloud that these were men from Liège. Fearing that their presence would be betrayed, the Liégeois drew their weapons and fell upon the unfortunate camp-followers.

The women were quickly killed, but one of them, who according to Onofrio fell or jumped into a pit, managed to cry out. Haynin writes that one of the raiders was already entering the duke’s lodging, but when the alarm was raised the raiders panicked and fled. Most other sources confirm that just the contrary happened. Realizing that it was now or never, some of the raiders spread out to create as much havoc as possible, setting fire to tents and baggage, while two special strike forces pressed straight for the bedrooms of the duke and king, guided home by the vengeful landlords. The main assault was launched on Charles’s lodging, to the cries of ‘Vive le Roi!’ The Liégeois still claimed to be the staunch allies of the king of France, and they may also have hoped to sow confusion amongst their enemies, and lead the Burgundians to believe that they were being attacked by the royal guards.

Charles awoke into a nightmare. The raiders were storming the entrances of his house, and had apparently killed one of his valets as well as two squires inside the house. The archers in the room above forgot about their game of dice, reached for their weapons, and ran down the stairs to save the duke. A fierce struggle ensued, the archers trying to buy a few precious seconds at the price of their own lives. The men-at-arms in the barn meanwhile snatched whatever weapons were at hand and rushed to the duke’s rescue. Inside Charles’s bedroom, Commynes and Charles’s two other pages were frantically trying to arm the duke, but had time only to put on his cuirass and breastplate and clap a steel cap upon his head. Commynes describes in his memoirs the din and confusion of those moments. All around the house and in the street outside there was terrible noise and uproar, the cries of ‘Long live Burgundy!’ mingling with the battle cry of both the royal guard and the Liégeois raiders: ‘Vive le Roi!’ Nobody knew for sure what was happening. Was it a Liégeois attack, or perhaps some more foul play by the treacherous Louis?

The king himself also woke up in trepidation. According to his page, Ludwig von Diesbach, the king’s lodging was set on fire, and the raiders almost managed to kill Louis. Commynes affirms that the raiders actually penetrated the house before they were repulsed by the Scottish guards. The Scots then placed themselves as a human shield all around Louis, and rained a hail of arrows on the confused melee outside, shooting down indiscriminately both Liégeois and Burgundians.

With each passing second, the raid’s chances of success diminished, as the raiders were beaten back from the two houses and more and more Burgundian soldiers armed themselves and joined the fray. Torches were brought to light the scene and clarify the situation, and soon the Liégeois were in full retreat. More light could have been thrown on these eventful moments by Olivier de la Marche. However, La Marche does not even mention the raid in his memoirs. According to a letter of Anthoine de Loisey, the Liégeois killed altogether about 200 men, including many camp followers and pages. They themselves appear to have suffered lighter losses. Haynin says that only fourteen of them were killed. Commynes writes that the landlord of the duke’s house, who guided and led the attack, was the first one to be struck down, though he survived a few hours more, and Commynes had personally heard him speak. The rest, headed by Streel, made it safely back to Liège.28

The following morning Liège was stormed. Little resistance was offered to the assailants. The city was thoroughly pillaged and burned to the ground. Charles personally supervised the destruction, and then sent a punitive expedition to wreak havoc in the region of Franchimont, from where most of his would-be killers hailed. He held on to Louis for a few more days, but ran out of excuses for delay, and had to either allow the king to depart, or to publicly confess Louis was now his prisoner. He opted for the former course. After exacting from Louis a few more worthless promises to abide by the treaty of Péronne, Charles reluctantly set him free.29

· · ·

THE treaty of Péronne became a dead letter within less than two years. By 1470 king and duke were again eyeing each other suspiciously, readying themselves for the next round. The propaganda war between them continued unabated. Charles continued to harp on his old themes of assassination and kidnapping, accusing Louis of fighting a dirty war. On 13 December 1470 Charles published an open manifesto in which he alleged that Louis stood behind a recent plot to assassinate or kidnap him. According to the most extravagant version of the events, Jehan d’Arson, a Burgundian nobleman who secretly joined the service of King Louis, contacted one of Duke Philip the Good’s many bastards, Baudouin of Burgundy, and made him a tempting offer. If Baudouin managed to rid the king of Duke Charles, by one means or another, Louis promised to give him the greatest rewards imaginable. Arson explained that Duke Charles had no children, save a single daughter, and if he died, his lands would be estranged and would be divided between many hands. Louis would then be able to reward Baudouin with any share of this inheritance that Baudouin might desire.

Baudouin agreed, and collected a group of disaffected noblemen to help him carry out the project. They intended to surprise Charles either at the park of Hesdin, where he often went hunting with only a small company, or during his visit to the port of Crotoy on the Picard coast (from where Rubempré had once set sail). They hoped to overcome his guards, and either kill him or carry him off to France. The plot was uncovered, though Baudouin and most of his accomplices managed to flee Burgundy in November 1470. Whether this story is true is not easy to judge. The only fact we can be certain of is that Baudouin and several other noblemen had indeed defected from Burgundy to France in November 1470, and received rather meagre rewards from Louis.30

In May 1472 Louis’s younger brother died, dashing any hopes that Charles of Burgundy and the leading French noblemen had of using him to check Louis’s power. Charles and his confederates immediately spread allegations that he had been poisoned on Louis’s orders, and even kidnapped a few of the dead man’s close servants who confessed their guilt, under torture. Modern scholars habitually discount these allegations as propaganda. Fifteenth-century public opinion took them more seriously, and Charles of Burgundy and his confederates seized upon them as a pretext for launching a combined military attack on Louis.31 At about the same time, Charles himself instituted elaborate precautions in his kitchens and dining halls against the threat of poisoning.32

Louis, for his part, responded with counter-accusations whose truthfulness is equally impossible to tell. In 1473 a poisoner named Jehan Hardy was caught in Louis’s kitchen. French propaganda accused him of being a Burgundian agent attempting to poison the king of France. In 1476 another poisoner was caught in the royal kitchens. This time the alleged target was the French crown prince.33

The heavy atmosphere of suspicion is best attested by the elaborate precautions taken during several summit conferences that were held in the wake of Péronne. When Louis met his brother, Charles of France, at Niort (1469), a bridge of boats was made to span over the river Sèvres, and in its middle was built a stout wooden grille. The two royal brothers met with this barricade separating them, so that they could talk and shake hands, but could not kill or kidnap one another. In 1475 a similar bridge was constructed over the river Somme at Picquigny for the peace conference between Louis and King Edward IV of England. In the middle, writes Commynes, a strong wooden trellis was placed, ‘such as lions’ cages are made with, the hole between every bar being no wider than to thrust in a man’s arm’ 34 The two kings spoke and hugged each other through the trellis. To further diminish the danger of assassination, some of the attendants of both kings came to the meeting dressed exactly like their masters.

In 1477 King Alfonso V of Portugal, who was a relative and ally of Duke Charles, visited France and tried to negotiate a peace treaty between the duke of Burgundy on the one hand and the king of France and his allies on the other. At some point, while he was residing in Paris, the Portuguese monarch grew suspicious that Louis was about to seize and deliver him to his bitter enemy, the king of Castile. Alfonso therefore disguised himself, and taking only two servants with him, tried to flee France. One of Louis’s lieutenants captured Alfonso, who aroused his suspicions. Louis, according to Commynes, was greatly ashamed of the entire episode. He had no intention of doing any harm to the Portuguese king, and to prove his innocence, conducted him safely back to Portugal.35

Despite these apparently widespread fears of Louis’s underhand methods, it was the abductor of Péronne who seemed to have acquired during those years a taste for kidnapping foreign princes. The first to learn this lesson were Dukes Adolf and Arnold of Guelders. During the 1450s and 1460s Adolf had been engaged in a bitter feud with his father, Arnold. Adolf, frustrated by his father’s extraordinary longevity, asserted that Arnold had ruled long enough, and it was time he stepped aside and allowed his son to have his turn. Arnold refused, and a state of virtual civil war ensued. For mediation the rivals turned to the duke of Burgundy, their powerful neighbour and long-time ally. For a time it seemed that Burgundian intervention forced a peaceful settlement on Guelders. However, on 10 January 1465 Adolf mounted a surprise attack on Duke Arnold’s castle of Grave, allegedly with Burgundian assistance. Arnold was captured, and spent the next five years locked up in the castle of Buren. Adolf became duke in his stead, but Arnold’s supporters refused to acknowledge his authority, and open war resulted.

In 1470 Adolf and his rivals travelled to the court of Duke Charles, then at the height of his power, to plead their cases and secure his support. In January 1471, either with or without Adolf’s consent, Charles sent Henric van Horne with a small Burgundian force into Guelders. Horne extricated Arnold from his prison, and brought him too before Duke Charles. Charles then kept both father and son at Hesdin, while the negotiations crept slowly on and the civil war in Guelders continued unabated.

Adolf grew apprehensive, fearing that Charles was intending to hold both him and his father as virtual prisoners, while taking over Guelders himself. On the night of 10 February 1471 Adolf secretly escaped from Hesdin. Charles combed the Low Countries for the fugitive duke. Adolf disguised himself as a travelling Frenchman, and accompanied by a single servant, tried to get back to Guelders. He nearly reached his destination, but while boarding a ferry near Namur he was recognized by a priest and apprehended. He spent the next six years under heavy guard in several Burgundian castles, despite repeated requests from foreign powers to release him. His father meanwhile disavowed him and adopted Charles of Burgundy as his heir, on 7 December 1472. This time, the old duke of Guelders did not keep his heir waiting for long. He died three months later. Charles quickly collected his armies and invaded Guelders to enforce his rights. By July the conquest was complete, and Guelders became part of the Burgundian patrimony.36

A year later, it was the turn of Count Henry of Württemberg. This seventeen-year-old youth inherited the strategically vital town of Montbéliard in the Upper Rhine region, which then absorbed most of Duke Charles’s expansionist ambitions. He had also inherited several fiefs within Burgundy. Though his rights there were infringed upon, he seemed to have been on good terms with Duke Charles.

In April 1474 Henry was travelling near Thionville with a small escort; he may have been intending to meet Duke Charles to settle the question of his Burgundian lands, or have been on a pilgrimage, or was on his way to meet the German emperor. When Charles heard of it, he dispatched a small force that intercepted and captured Count Henry. In prison the count promised to surrender Montbéliard to Charles in exchange for his freedom. Olivier de la Marche was given charge of the delicate mission. Taking the count along with him, La Marche appeared before the walls of Montbéliard and threatened the garrison that if they did not surrender the place, he would behead their lord and master. The garrison shut their ears to La Marche’s threats as well as to Count Henry’s desperate pleas. Since this psychological attack failed, and since a conventional attack on the heavily fortified town was out of the question, La Marche had to return to Charles empty-handed. The angry duke threw Count Henry back into prison, holding him first at Maastricht and then at Boulogne. The young count was devastated by this turn of fortune’s wheel, and went insane. Charles kept him in prison nevertheless; he was finally released only after the duke’s death, a broken man.37

Duke Charles himself was also beginning to show signs of insanity. He had now reached the pinnacle of his power, but success went to his head, and he started overreaching himself. During the next four years, while King Louis watched and held his armies at bay, Charles got bogged down in messier and messier adventures. He attempted almost simultaneously to conquer Alsace, Lorraine, and Cologne, as well as to establish a protectorate over Savoy. These attacks, coupled with adroit French diplomacy, forged a powerful anti-Burgundian coalition of German powers, led by the cities of the Rhine basin and Switzerland. The stubborn Charles repeatedly hurled himself against this coalition, losing campaign after campaign. The flower of the Burgundian army was squandered during the barren siege of Neuss (1474/5). Another army was routed on 2 March 1476 by the rising power of the Swiss at the battle of Grandson. By June Charles had reassembled a third army, which was massacred by the Swiss at Morat on 22 June 1476.

This string of disasters broke Burgundian military power, and Charles lost his most recent conquests one by one. King Louis seemed poised to attack his rear, and the many allies that flocked to join Charles during the rosy day of his success now turned their backs on him. While trying to collect a new army, Charles made desperate attempts to retain the alliance of at least one crucial alley, the Duchy of Savoy. Savoy not only guarded his south-eastern flank and threatened the southern flank of his Swiss enemies, but it also controlled the routes to Burgundy from Italy, from where Charles now obtained most of his mercenary soldiers.

After the death of Duke Amadeus IX in 1472, his son Philibert was proclaimed duke of Savoy. Philibert, however, was merely seven years old, so his mother Yolanda ruled as regent. Though Yolanda was sister of the king of France, she was a firm ally of Burgundy throughout the 1470s, partly because Charles tempted her with promises of marrying his daughter Marie to Philibert. Indeed, the conflict between Burgundy and the Swiss was largely a result of Burgundian attempts to protect Savoy against Swiss imperialist encroachments, and the campaigns of Grandson and Morat were both fought on Savoyard territory in order to repel Swiss invasions. It is interesting to note that by 1475 Yolanda had around her person a guard of eighty Burgundian mercenaries, though it was not absolutely clear whether they were protecting her or supervising her.38

After Grandson, Burgundian control over Savoy was only strengthened, as Yolanda became completely dependent on Burgundian help to ward off the Swiss. On 22 March 1476 Yolanda and her five children came to meet Charles at Lausanne to reassure him of their continued loyalty. They also sent 4,000 men to join Charles’s resuscitated army. They remained under Burgundian supervision henceforth, while Charles placed Burgundian garrisons in several Savoyard strongholds. It is not easy to understand how any princess could have willingly entrusted herself and her children to the Burgundian serial kidnapper at this date.