In most shooting and fishing households it is the menfolk who have the pleasure of the day in the field and it seems to me only fair that they should also prepare the game they have brought home and present it ready for the oven to the sporting wife. These days many wives like to join in the sport either as a gun, walking with the beaters or picking up with the family gundog and, in many households, they seem quite happy to do all the plucking. Others choose to stay at home to share the secondhand excitement of the day’s sport during the ‘action replay’ over supper by the fire.

Most men can be persuaded to prepare the bag for the table if it is just a brace of birds or a single rabbit or hare, but there are times, such as after a successful day decoying pigeons when the bag is much larger, and in warmer weather when speed is important, when it is a case of many hands making light work. On these occasions every wife should be prepared to muck in. Involving children in the plucking chore can be a time saver once they have practised a few times. Most children are prepared to have a go, especially if a small fee per bird is involved. Bear in mind, though, that their stamina is limited: fingers will tire quickly and many children find the wing and tail feathers too tough, so be prepared to do a little tidying up! However, if the family does not rise to the occasion, you can always pay your local butcher or odd-job man to prepare the game for you. Certainly this is advisable if you have a whole carcass of venison to deal with as few of us have the necessary space, equipment or expertise to prepare so large an animal.

This chapter makes the necessary general points about making game fit for the table; special hints are given for each particular species in the appropriate chapter.

The reason for hanging game is to enable the fibres of the flesh to break down so that the meat will become more tender and also to improve the flavour. There is no fast rule which states how long to hang birds or ground game as much depends on the weather and individual tastes of the consumer. A September grouse may need hanging for only two days, whereas a cock pheasant shot in cold January will hang for two to three weeks and still be in perfect condition. Some like to cook or freeze their game within twenty-four hours, while die-hard traditionalists prefer to hang theirs until they are ‘high’ and the flesh around the vent has turned bluish-green. In extreme cases, a bird is hung until it literally drops off the hook in what many would consider a fairly advanced state of putrefaction. Hanging also increases the ‘gamey’ flavour, so very young birds will lose their delicate taste if hung for too long.

Weather and personal tastes aside, there are some useful guidelines concerning hanging. Game birds in the United Kingdom are traditionally hung by their necks; the French hang a bird by one leg to allow air to circulate under the feathers. Rabbits and hares are hung by their back legs. Always hang birds individually, with a string tied around the neck, never as a brace, so that the air can circulate freely around each one. A stout nail in a wall makes a perfectly adequate hanging point, but better still is a game hanging rack. Each head of game is hung individually in the angles of a metal, diamond-gridded frame screwed to the wall at an angle. No strings are needed and each bird has a layer of air all round; the bird’s own weight holds it firmly in position and the device will take anything from a snipe to a hare. Keep game out of direct sunlight — a cold shed or garage is ideal — and high enough to be out of reach of dogs, cats and rats. During the early part of the season, in blow-fly time, a fly-proof larder is a good investment as without it birds become maggot-ridden within hours. It is a good idea to keep very badly damaged birds separate from the rest and hang them for a shorter time.

Game birds are traditionally hung by their necks. Rabbits and hares are hung by their back legs

There is much unnecessary mystique surrounding the hanging of game, but there is no doubt that it does improve the flavour and help to tenderise the meat, but the determining time factor must be your individual taste for, after all, you are the consumer!

To cook any game successfully it is important to know the age of the bird or animal. Young game is the more desirable as it is tender and suitable for the quicker cooking methods such as roasting, grilling or frying. Older and therefore tougher game needs to be braised, casseroled, pot-roasted or prepared in a pressure cooker.

The bursa test, using a blunt matchstick. The bursa can be seen just below the left thumb

There is only one method of ageing which may be applied to all game birds: the bursa test. All young game birds have a small blind-ended passage or bursa, opening just above the vent. To find this, open out the vent area with the thumb, and the bursa, if present, should be clearly seen. The end of a matchstick or quill feather can then be carefully inserted into the bursa. In a young pheasant it will penetrate to a depth of about 2.5cm (lin) and in a young grouse or partridge to a depth of about 1cm (1⁄2in). In all species the bursa becomes much reduced or may close completely when the bird is sexually mature.

Each individual game species has additional features which help to distinguish young from old and these will be more fully described in the appropriate chapter.

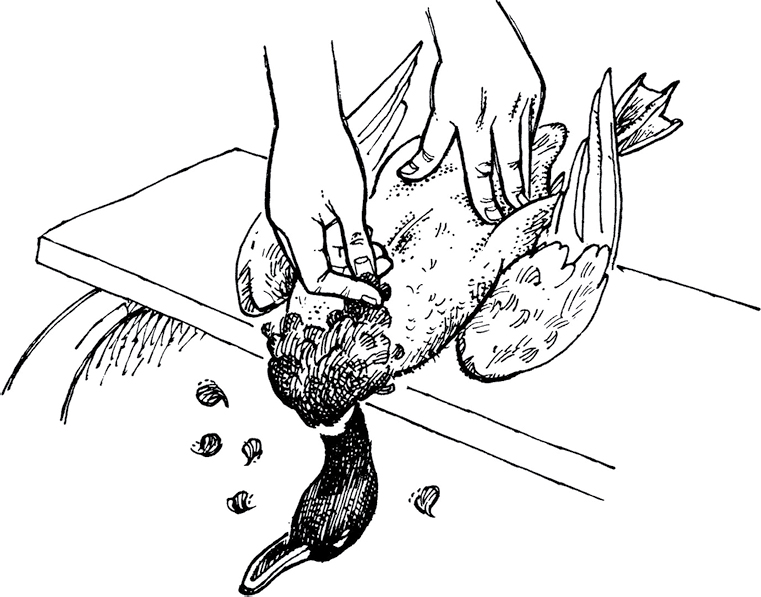

Plucking should be done out of doors in a sheltered spot or in a shed or garage as there are bound to be some flying feathers. Wear a large apron or overall and pluck the birds into a large box or dustbin. For larger birds it is a good idea to lay them on a board over the bin.

Start by fanning the wings and pulling out the primaries, then work in towards the body. There is no need to pluck completely the end wing joint of the smaller game birds as there is so little meat on them, so cut off the wing at the joint. The wings of duck may be removed altogether for they carry virtually no flesh and are very tedious to pluck. Likewise, if a wing has been badly damaged it should be cut off completely. Continue with the neck and work down to the tail, pulling the feathers against the grain. Take care not to tear the tender skin on the breast and neck otherwise the meat dries out during cooking. Pull out any remaining quill ends; use pliers for stubborn ones.

Lay large birds on a board and pluck the feathers into a dustbin

If you are using a bird for a pâté, casserole or pie, which will usually be the case if it is badly damaged, or if you require just the breast meat, it is much quicker to skin rather than pluck.

Cut off the head and clip off the wings and legs with secateurs. Lay the bird on its back and, with a sharp knife, cut the skin lightly along the breastbone and peel it off in one piece. This works especially well with wildfowl. Other game birds may shed a few feathers in the process which cling to the flesh, but these can easily be washed off under the tap. If you require only the breast meat, simply peel back the skin to expose the breast, then make a cut under the lower end of the breastbone, cut deeply along the ribs close to the wings and then through the collarbones with the secateurs. Remove the whole breast in one piece on the bone.

Skinning a duck. Using a sharp knife cut the skin lightly along the breastbone

Before starting this operation, make sure you have all your equipment handy. You will need a small sharp knife, a pair of stout kitchen scissors or an old pair of secateurs, a skewer and a bucket for the intestines. In our household very little is discarded, as what we or the dogs do not eat, the ferrets will!

Using a sharp knife cut off the head at the top of the neck.

Loosen the skin around the neck and draw out the windpipe and crop, being careful to avoid breaking the crop.

Cut off the neck as close to the body as possible, leaving the loose skin intact, to be folded over the back later when trussing.

Make a cut above and below the vent and remove it. Gripping the bird around the breast with the one hand, insert two fingers of the other hand into the body cavity. Reach up under the breastbone and pull out in one clean movement the heart, gizzard, liver, gall-bladder and intestines.

Removing the tendons from the leg of a pheasant

Keep the heart, gizzard and liver but discard the intestines and the gall-bladder without puncturing it.

Split the gizzard, peeling off and discarding the lining and contents, and wash in cold water together with the heart, liver and neck and keep them for making stock. The liver may be saved for pâté.

Make a nick across the knee joint, being careful not to cut through the tendons. Break the joint by hand and pull the two ends apart: some of the tendons should draw out, but if they don’t, use a skewer to hook them out one at a time.

Wash the bird inside and out under cold running water and dry thoroughly with kitchen paper or a cloth.

Trussing a pheasant

The reason for trussing a game bird before roasting is to keep it compact during cooking to help prevent it from drying out. It also improves the appearance of the bird on the table and makes it easier to carve. However, trussing a game bird is often more difficult than a chicken as you will not always have the benefit of a perfect bird; the skin may be torn, a leg or wing broken or missing, so you may have to improvise using skewers and string. For smaller birds, such as grouse and partridge, use cocktail sticks.

Place the bird on its breast and pull back the wings close to the side of the body.

Push a skewer through the wing just below the first joint, through the body and out through the other wing.

Pull back the neck skin.

Take a piece of string about 45cm (18in) long and place around the ends of the skewer, catching the neck flap underneath, then cross the string over the back of the bird and tie it around the parson’s nose.

Turn the bird onto its back, pull the legs together and tie the string firmly around the drumsticks, pulling them towards the parson’s nose. If the legs are damaged you may have to pass a second skewer through them on which to tie the string.

If you wish to cook a bird in portions you will find game shears a very useful investment, but a sharp knife and a sturdy pair of kitchen scissors will do.

Place the bird breast side down on a table or chopping-board. With a small sharp knife cut along the backbone through skin and flesh. With game shears or scissors, cut through the backbone and open the bird. Turn it over, breast up, and continue cutting along the breastbone which will split the bird into two equal halves. You may either leave the backbone in place or remove it altogether, together with any remaining innards. Try also to work out any loose pellets of shot which often lodge under the skin.

Jointing a gamebird. Cut through the backbone using game shears

Purists prefer to eat only fresh game in season while others are less particular, but one of the virtues of owning a deep freeze is that you can enjoy cooking and eating game at any time of the year. Whatever your feelings, there are times when a freezer is invaluable, for in a shooting household there will be occasions when the bag is too large for your immediate needs. Unless you give away your surplus game, freezing it for future use is the obvious answer.

When preparing a game casserole or soup it is a good idea to cook double the quantity you need and to freeze half of it. ‘Eat one and freeze one’ will save you time and cooking energy, and you will have a supply of instant meals for those occasions when you are too busy to spend much time in the kitchen. The meal may be defrosted and reheated on the stove or recooked in a microwave oven.

There is no virtue in freezing game in feather and fur unless you are really pushed for time and have a large number to deal with. Feathered game takes up more room in the freezer and, once thawed, plucked and drawn, it must be cooked and not refrozen, although it may be safely frozen after cooking. Pigeon shooters often like to keep a few birds frozen in their feathers to use as decoys.

Birds should be plucked or skinned and drawn. Remove any visible shot from under the skin, wash them out and dry thoroughly. Wrap in foil or grease-proof paper any sharp protruding bones and pack in heavy-gauge freezer bags or at least two ordinary polythene freezer bags. Alternatively, wrap in aluminium foil, which can be easily moulded to the shape of the bird, then seal in a polythene bag. Expel all the air and seal the bag tightly as any air leaks can cause the meat to dry out.

Finally, label the bag carefully, showing the species, whether young or old and the date. It is also a good idea to include other useful cooking information; for instance, if you have a really clean bird with both legs and wings intact, and the skin untorn, it would be worth indicating that it is suitable for roasting. You may have several young hen pheasants which could be saved for a special occasion, such as a dinner party, in which case label them accordingly. Likewise, an old tough January cock pheasant should be labelled ‘casserole’ to remind you not to roast it. If you enjoy cooking on a barbecue or open fire in the summer, or wish to grill young game birds or rabbit, these can be jointed and clearly labelled before freezing.

Badly shot birds are best cooked immediately and then frozen for later use in pies or pâté.

Most uncooked game may be stored for between six and nine months, although I have frequently found a ‘lost’ bird in the bottom of the freezer which had been there for longer than this yet it has still cooked perfectly.

Livers for pâté should be cleaned, have the gall-bladder removed and be packed separately in margarine tubs or polythene bags and may be stored for up to two months uncooked, but only one month if cooked. Cooked game dishes may be frozen for up to three months. It is better to undercook casseroles and add some fresh vegetables when reheating the dish. Roasted birds do not freeze well as the flesh tends to lose moisture and become flabby.

Game pies may be completely cooked before freezing, or the filling only may be cooked and allowed to cool, then topped with pastry and frozen unbaked. They will keep for up to two months. Cooked hot-water crust pastry does not freeze well as it tends to crumble when thawed, and freezing the pastry unbaked can be dangerous as the hot water used to make the pastry might contaminate the meat.

As pâté tends to be highly seasoned it, too, does not freeze well, but if it is sealed with melted butter it will keep for up to two weeks in the refrigerator. Soup freezes well but add starchy ingredients, milk or cream when reheating. Pack in watertight containers, allowing 1cm (1⁄2in) head space, and store for two months.

All meat should be allowed to thaw out slowly, preferably overnight, in a cool place.

Finally, try to use game in reverse order of storage, the oldest first, and whenever possible have the freezer empty for the start of each new season.