No close shooting season

One cannot envisage the countryside without the familiar sight of the rabbit for it is common throughout the British Isles.

The pelt of a rabbit has no fewer than three coats: a soft dense undercoat providing warmth and two outercoats giving a waterproof protection. The colour of the fur comes from these two outer coats and is predominantly grey-brown on the upper side, turning to reddish-brown at the back of the neck. The colouring is lighter underneath and the throat is white. The short fluffy tail, or scut, is brownish-black above and white underneath. The hind legs are much longer and stronger than the forelegs. The sexes are alike in colouring, but the male or buck may be slightly larger than the female or doe, with a shorter, thicker head and ears which may be torn from fighting.

The rabbit favours a moderate climate and inhabits heathland, sand dunes and fen country where the soil is soft for easy burrowing; it can also be found in woodland adjacent to open farmland where there is a good source of food. The rabbit feeds mainly on grass but can also cause severe damage to farm and garden crops and the bark of young saplings.

It is generally believed that the rabbit was introduced to this country by the Normans during the twelfth century when they were bred and protected in warrens. Some of the Norman conquerors arrived in England with warrener and his ferrets in tow. Rabbits were highly valued both for their meat and fur and frequently featured on the menu at impressive feasts such as coronations and enthronements of archbishops. The rabbit fetched a high price throughout the Middle Ages and in the seventeenth century they cost 8d a couple compared with only 4d for partridge.

The growing need for food in this country led to the gradual spread of warrens when land was set aside for the specific purpose of breeding rabbits, which, although confined by the boundaries of the warren, were otherwise quite wild. Landowners employed warreners to maintain the fences in a good state of repair to contain the rabbits and to keep out marauding foxes and poachers.

By the end of the nineteenth century rabbit warrens were becoming scarce owing to improved agricultural knowledge and techniques which made better use of the land through the cultivation of cereals and root crops. But the release of the rabbits was some farmers’ downfall. One tenant farmer on a great estate was said to have committed suicide, saying: ‘Rabbits have killed me.’ They had fed on his crops and deprived him of his living. This was before the passing of the Ground Game Act in 1880 which gave tenants the right to kill rabbits on their land, thus giving some protection to their crops.

The additional source of food which the introduction of new crops gave to the rabbit, together with the growing interest in shooting for sport rather than just filling the larder, led to a startling growth in the rabbit population so that by 1953 it was estimated at between sixty and one hundred million.

Then in autumn 1953 came myxomatosis like the plague of the fourteenth century and in a matter of months the rabbit was almost eliminated, to such an extent that in some areas only one rabbit in two hundred survived. The disease had been known in some parts of the world for centuries and had been used in Australia in the 1950s to control the rabbit population. It is not certain how the virus reached England, but it was first reported in Kent in 1953 and from there it gradually spread until, a year after its arrival, there were over 250 outbreaks of the disease in 61 counties.

During the following thirty years numbers have steadily recovered as the rabbit has become virtually immune to the virus and a new generation has adapted to living above ground in small colonies where they are less vulnerable to the disease.

Today, the rabbit is almost as big a pest as ever, doing millions of pounds’ worth of damage to farm crops, especially young corn, and even raiding garden produce. Landowners are legally required to control the rabbit population under the Pest Act of 1954. This is usually done by gassing, but there was talk of legalising the use of poisoned baits for controlling rabbits, a suggestion which many people view with alarm, and it would certainly not be well received by the great army of ferret owners should their traditional quarry and their sport be taken from them. A ferreted rabbit is highly prized as it is free from shot and therefore in clean condition. Much the same applies to a rabbit shot with a .22 rifle. The marksman aims for a head, neck or heart shot which result in clean kills and a minimum of damaged flesh. Rabbits peppered with shot-gun pellets, a mass of shattered bones and broken blood vessels are not popular in the kitchen and even the best cook cannot do justice to meat spoiled in such a way.

Imported rabbit meat is regaining popularity with the British public and is widely available both fresh and frozen from butchers’ shops and supermarkets, although the wild rabbit has more flavour than those specially bred for the table.

Rabbits should be paunched as soon as they are cool. First ‘thumb’ the rabbit towards the vent to expel any urine from the bladder. A bladder punctured during paunching can cause the meat to become tainted. Using a sharp knife, cut the belly skin from vent to sternum and remove the intestines and stomach.

In summer rabbits are best skinned the same day but in cooler weather they may be hung in a cool place by their hind legs for one to four days.

Thumb the rabbit towards the vent to expel any urine from the bladder

Paunching. Using a sharp knife cut the belly skin from vent to sternum

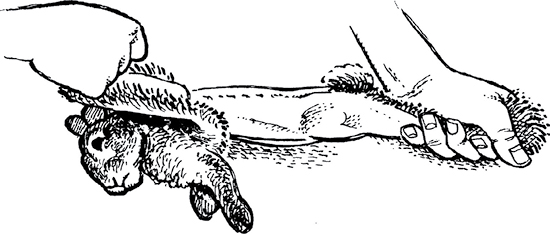

Ageing a rabbit. In a young rabbit, the lower jaw should yield to pressure between the thumb and first finger

A young rabbit should be plump, with smooth fur, soft ears and smooth claws. The lower jaw should yield to pressure between the first finger and thumb. As a rabbit ages its ears become more leathery and the claws lengthen. A rabbit reaches adult size at four months and it then becomes more difficult to tell young from old. Some indication of a rabbit’s age is how easy it is to skin. If the skin comes off easily and is inclined to tear, the rabbit is likely to be young.

Lay the rabbit on a worktop or table with its hind feet towards you. Start with the hindquarters by pulling the loose belly skin firmly towards you and peel it off around the tail and hind legs. Pull the legs out of the skin. Cut off the feet with secateurs at the heel joint and remove the tail. Turn the rabbit around and work the skin up over the head, pulling the front legs out. Cut off the front feet with secateurs and the head with a sharp knife. The head and complete skin may then be discarded.

Skinning a rabbit

Cut the diaphragm enclosing the heart and lungs inside the rib-cage. Keep the heart but discard the lungs. Remove and keep the kidneys and liver, which, together with the heart, may be used for stock. Wash the rabbit thoroughly in cold water, then leave to soak in cold salt water overnight. Rinse again in cold water before cooking or freezing.

Leave young rabbits whole for roasting. More mature rabbits should be jointed and used for stews, casseroles and pies.

Cut off the hind legs where they join the backbone and remove the front legs from the rib-cage. The back may then be cut into two or three joints. If you are preparing a number of rabbits for the freezer, keep back the top joint which includes the neck and rib-cage. There is very little meat on this joint and it is a minefield of tiny bones. Cook these separately and when cold strip the meat from the bones and use it in a game pie or pâté.

Young roast rabbit is improved with the addition of a savoury stuffing and covered with bacon to prevent the meat from becoming dry. A young rabbit cut into joints may be successfully cooked under the grill. As when roasting, to keep the flesh moist, either wrap a rasher of bacon round each joint, or alternatively, coat it in beaten egg and breadcrumbs. Older rabbits can be made more tender if marinated in wine, cider or beer before cooking. Virtually any chicken recipe will suit rabbit. One full-grown rabbit will serve four people. Rabbit may be stored for up to nine months in the deep freeze.

A young rabbit may be roasted with a savoury stuffing and plenty of fat bacon to keep the flesh moist. Sage and onion stuffing goes well with rabbit, but you may like to try sausagemeat and apple, or apricot, walnut and orange for a change (see Good Companions).

1 young rabbit

8 rashers streaky bacon

Sage and onion stuffing

1tbsp sherry

Salt and pepper

Fill the body cavity of the rabbit with the sage and onion stuffing and sew the loose skin together.

Place in a roasting tin and season with salt and pepper. Lay the streaky bacon over the rabbit and cover the tin loosely with foil. Roast in a fairly hot oven, 200°C (400°F), gas mark 6, for 1 hour.

Remove the foil and bacon, baste well and return to the oven for a further 15 minutes. Roll the bacon rashers and return these to the oven to crisp.

Place the rabbit and bacon rolls on a serving dish and keep hot.

Add the sherry to the pan juices to make a thin gravy and serve the rabbit with roast potatoes, bread sauce and redcurrant or quince jelly (see Good Companions).

Young rabbit joints are braised in stock with potatoes and parsley. White wine, yoghurt and mushrooms are added to make a delicately flavoured sauce which is thickened with the puréed potatoes.

1 young rabbit, jointed

600ml (1pt) chicken stock

225g (8oz) potatoes, peeled and sliced

1tbsp freshly chopped parsley

1 clove garlic

150ml (1⁄4pt) white wine

100g (4oz) button mushrooms

150g (5oz) natural yoghurt

Salt and pepper

Sprigs of fresh parsley and thyme to garnish

Crush the clove of garlic with a little salt in a saucepan. Add the rabbit joints, sliced potatoes, parsley, pepper and stock which may be made with a stock cube. Simmer for 1 hour.

Rub the potatoes through a sieve and return to the saucepan. Add the button mushrooms, wine and yoghurt and heat gently for another 30 minutes. Adjust the seasoning if necessary.

Arrange the rabbit joints on a warm serving dish, pour over the sauce and decorate with sprigs of fresh parsley and thyme.

Young rabbit joints are poached in a sweet and sour sauce. The meat is taken off the bone in fork-sized pieces and served with salads, rice or pasta to make an ideal dish for a buffet party. It may easily be prepared the previous day and reheated just before serving.

2 young rabbits, jointed

432g (151⁄4oz) pineapple pieces in natural juice

6 large tomatoes, chopped

1 large green pepper, deseeded and chopped

1 large onion, finely chopped

1tbsp soft brown sugar

2tbsp white wine vinegar

2tbsp soy sauce

Salt and pepper

1tbsp cornflour

Soak the rabbit joints in cold water for 24 hours, then rinse thoroughly.

Place all the ingredients, except the cornflour, in a large saucepan and simmer gently for 1 hour or until tender.

Allow the rabbit joints to cool, then remove the meat from the bones, breaking it into small pieces.

Mix the cornflour with a little water, blend into the sauce and bring to the boil, stirring all the time.

Return the rabbit meat to the sauce and reheat gently. Turn into a large warm shallow dish and serve with plain rice or pasta and a variety of salads.

During the summer young rabbit joints may be successfully cooked on a barbecue as a change from chicken, sausages or burgers. Marinate the joints for 24 hours before cooking. Marinades usually contain an acid such as wine, wine vinegar or lemon juice to tenderise, oil or butter to add moisture and herbs or spices to give extra flavour. The joints should be basted frequently and turned with tongs during cooking. Do not pierce with a fork or you will lose the natural juices. Both marinade and sauce are uncooked and are quick to prepare.

Young rabbit joints (allow 2 — 3 per serving)

4tbsp oil

4tbsp wine vinegar

1 small onion, chopped

1tsp crushed rosemary

Salt and pepper

2tbsp tomato purée or ketchup

1tbsp red wine vinegar

1tbsp Worcestershire sauce

1tsp French mustard

1tbsp lemon juice

1tbsp brown sugar or honey

Place the rabbit joints in a shallow dish. Pour over the marinade and leave overnight in the refrigerator.

Oil the grill and heat for 30 minutes before starting to cook. Brush the joints with the marinade and grill for 10 minutes on each side, basting frequently with the marinade.

Brush with the barbecue sauce and continue cooking until the meat is golden brown. Serve with the rest of the sauce, a plain green salad and some crusty bread.

Joints of rabbit cooked in a creamy mushroom sauce is a popular dish in France. Rice makes a good accompaniment.

6-7 rabbit joints

Stock or water to cover the meat

1 large onion, sliced

225g (8oz) mushrooms

50g (2oz) flour

150ml (1⁄4pt) single cream

Pinch of nutmeg

4 cloves

Bay leaf

Salt and pepper

Chopped parsley to garnish

Soak the rabbit joints in cold salt water for 2-3 hours or overnight. Rinse in cold water.

Place the joints in a saucepan with the sliced onion, bay leaf, cloves, nutmeg, salt and pepper. Add enough stock or water to just cover the meat. Cover and simmer for 11⁄2 hours.

Strain off the stock which should be about 450ml (3⁄4pt).

In a small saucepan, blend the flour with a little water. Gradually add the strained stock and stir until boiling, then stir in the cream.

Place the mushrooms in the saucepan with the rabbit and pour over the sauce. Heat through gently for 30 minutes.

Turn the fricassée onto a hot serving dish, sprinkle with chopped parsley and serve with boiled rice.

This recipe revives childhood memories of returning home from school cold and hungry on a winter’s evening to the welcoming sight and smell of rabbit and dumplings simmering on the Rayburn. In those days rabbit regularly provided a warm and filling family meal for country folk.

1 rabbit, jointed

1 chicken stock cube, dissolved in 450ml (3⁄4pt) boiling water

3tbsp wholemeal flour

225g (1⁄2lb) parsnips, sliced

225g (1⁄2lb) carrots, sliced

225g (1⁄2lb) leeks, sliced

2 bay leaves

4 cloves

Salt and pepper

100g (4oz) self-raising flour

50g (2oz) shredded suet

Salt and pepper

Cold water to mix

Blend the flour with a little cold water in a saucepan or flameproof casserole. Gradually add the chicken stock and bring to the boil, stirring all the time.

Add the rabbit joints, all of the prepared vegetables, cloves, bay leaves, salt and pepper. Cover with a well-fitting lid and simmer until the rabbit is tender. This may take 11⁄2-21⁄2 hours, depending on the age of the rabbit. Do not overcook or the meat will fall off the bones.

Mix the ingredients for the dumplings with just enough cold water to make a firm, stiff dough. Divide into four dumplings and add to the saucepan, replacing the lid carefully, and simmer for 20 minutes.

Serve at once with creamed potatoes.

This recipe is from Clare Graham, once proprietress of the highly rated Rescobie Hotel in Glenrothes. Bacon, onions and cider add a rich flavour to the gravy.

1 rabbit, jointed

225g (8oz) streaky bacon

2 large onions, thinly sliced

75g (3oz) butter

2tbsp flour

150ml (1⁄4pt) dry cider

300ml (1⁄2pt) chicken stock

1 bouquet garni

Chop the bacon and fry in butter with the onions. Brown the rabbit joints in the same fat and place in a casserole. Add the bouquet garni. Sprinkle the bacon and onion mixture on top.

Add the flour to the remaining fat and make a roux. Gradually add the cider and stock to make a gravy. Pour the gravy over the rabbit, cover the casserole and cook in a moderate oven, 180°C (350°F), gas mark 4, for 2 hours.

Serve with baked potatoes and a green vegetable.

Marinating an older rabbit for a few days will help to tenderise the meat. Try a strong ale such as Theakston’s Old Peculier, a well-known Yorkshire brew, as a change from wine or cider.

1 rabbit, jointed

300ml (1⁄2pt) Theakston’s Old Peculier (or similar strong ale)

1 small onion, chopped

Crushed bay leaf

4 cloves

1 small tin tomatoes

1tbsp wholewheat flour

1tsp dried basil

Place the rabbit joints in a flameproof casserole. Add the onion, cloves, crushed bay leaf and ale. Leave for 2-3 days in a cool place.

Simmer on top of the stove for 2 hours.

Drain the tomatoes and add to the casserole.

Blend the flour with the tomato juice and stir into the casserole together with the basil. Continue to cook for another hour or until the rabbit is tender.

Rabbit pie has been traditional country fare for many centuries. Any assortment of vegetables may be added together with some field mushrooms for extra flavour.

1 rabbit, jointed

1 onion, chopped

450g (1lb) mixed root vegetables, chopped

100g (4oz) field mushrooms, sliced

600ml (1pt) chicken stock

25g (1oz) wholemeal flour

Salt and pepper

225g (8oz) flaky pastry

Beaten egg

Blend the flour with the stock in a large saucepan and bring to the boil, stirring all the time. Add the rabbit joints, the chopped vegetables, salt and pepper. Cover and simmer for 1 hour.

Place a funnel in the centre of a pie dish and arrange the rabbit joints in the dish. Add the vegetables and gravy and cover with flaky pastry. Make a hole in the centre, decorate with the pastry trimmings and glaze with the beaten egg. Cook in a fairly hot oven, 200°C (400°F), gas mark 6, for 45 minutes.

Serve hot with potatoes and a green vegetable.

Poacher’s Pie

Cider and apples go well with all game meat and rabbit is no exception. The rabbit joints are cooked on a bed of apples. After cooking, yoghurt is added to the apple purée to make a smooth, creamy sauce.

1 rabbit, jointed

675g (11⁄2lb) cooking apples

1 small onion stuck with 4 cloves

300ml (1⁄2pt) dry cider

Bay leaf

150g (5oz) natural yoghurt

1tbsp sugar

Parsley to garnish

Marinade the rabbit joints overnight in the cider together with the onion and bay leaf.

Peel, core and quarter the apples and place in a large saucepan. Lay the rabbit joints on top of the apples and pour the marinade over the rabbit. Bring to the boil and simmer gently for 11⁄2-2 hours or until the rabbit is tender. Remove the joints from the saucepan and keep hot on a serving dish.

Strain the sauce, remove the onion and bay leaf and rub the apples through a sieve.

Pour the liquid and apple purée back into the saucepan, add the sugar and bring to the boil.

Stir in the yoghurt and heat gently for 5 minutes without boiling.

Pour the sauce over the rabbit and decorate with parsley.

Curried dishes are best made with fresh rather than cooked meat, and as they require a long, slow cooking method to develop the flavour, this is a good way to prepare older rabbits.

6 rabbit joints

50g (2oz) butter

1 small onion, chopped

1 cooking apple, chopped

4tbsp curry powder

1tbsp wholewheat flour

600ml (1pt) chicken stock

1tbsp mango chutney

1tbsp brown sugar

Juice of 1 lemon

Salt and pepper

Melt the butter in a flameproof casserole and add the onion and apple. Cook gently until soft.

Stir in the curry powder, then add the stock and bring to the boil. Add the rabbit joints, chutney, sugar, lemon juice and seasoning. Cover and cook in a moderate oven, 180°C (350°F), gas mark 4, for 2 hours or until the rabbit is tender.

Remove the rabbit joints and keep hot on a serving dish.

Blend the flour with a little cold water and stir into the curry sauce. Stir over the heat until the sauce has thickened.

Pour the sauce over the rabbit and serve with boiled rice, sliced tomatoes, banana and green pepper.

Only in New Orleans, home of hot food and jazz, would you find jambalaya, gumbo, Creole shrimp or spicy rabbit stew bubbling in huge cauldrons on gas burners set on the grass verge beside the parade route during Mardi Gras. Thanks to friends from that vibrant city for this recipe.

1 rabbit, jointed

225g (8oz) smoked pork sausage, sliced

1 large onion, chopped

3 stalks celery, chopped

1 green pepper, deseeded and chopped

1 large can chopped tomatoes

2 cloves garlic, chopped

1 green chilli, deseeded and chopped

1tsp lemon zest

Oil for frying

1tbsp flour

450ml (3⁄4pt) chicken stock

Salt and black pepper

150ml (1⁄4 pt) red wine

2tbsp balsamic vinegar

2tbsp olive oil

1 clove garlic, crushed

Sprig of rosemary

2 bay leaves

Mix the ingredients for the marinade, pour over the rabbit and leave overnight in the fridge. Drain the rabbit and reserve the marinade.

Heat the oil in a sauté pan and brown the rabbit joints. Remove the rabbit then soften the onion, celery, green pepper, garlic and green chilli in the pan. Blend the flour into the reserved marinade and add to the pan. Stir in the stock and bring to the boil.

Add the rabbit joints, tomatoes and lemon zest, salt and pepper. Cover and simmer gently for one hour. Add the smoked sausage and top up with more stock if necessary.

Cook for a further 30 minutes or until the rabbit is tender. Check the seasoning and serve with rice and a green salad.

Use young rabbit meat as an alternative to chicken for stir fries and experiment with an available variety of ingredients from the East.

Meat from a young rabbit, sliced into strips

2tbsp white wine vinegar

2tsps runny honey

1cm (1⁄2 in) fresh root ginger, grated

1 clove garlic, crushed

1tsp Chinese 5 spice

2tbsp rapeseed oil

4 spring onions, finely chopped

1 yellow pepper, deseeded and sliced

100g (4oz) mushrooms, sliced

300g (11oz) bean sprouts

50g (2oz) unsalted cashew nuts

250g (8oz) fresh noodles

2tbsp soy sauce

2tsp Thai sweet chilli sauce

Black pepper

Chopped coriander

In a bowl combine the vinegar, honey, ginger and garlic and Chinese 5 spice. Add the rabbit and mix well.

Heat the oil in a wok or large sauté pan and stir fry the rabbit for 3-4 minutes or until cooked through.

Add the pepper, onions and mushrooms and stir fry for 2 minutes, then add the bean sprouts and cashew nuts and stir fry for another minute. Stir in the noodles and season with soy sauce, Thai sweet chilli sauce and black pepper.

Sprinkle with chopped coriander and serve at once.