1

Close your eyes and imagine a place where you feel most happy. How often is this an urban scene? When considering where it is most healthy to raise your children, do you instantly picture a rural idyll, and the pleasures of a life conducted around the village school gates? Returning, as most of us do, to the reality of city life, are the frustrations of the packed train carriage on your rushed commute to work always balanced by the proximity to art galleries, good cinemas and gourmet food shops? And what of that particular loneliness that comes from walking the city by oneself? Sometimes it feels liberating, but how far away is the threat of danger, of becoming lost, of losing one’s sense of self?

I was born in London and by the age of ten I was travelling around the city by bus on my own, exploring the places beyond my neighbourhood, realising that the metropolis was far larger and more diverse than anything I could imagine. Broader than the limits of my childish comprehension, London became the definition of the world itself. And when I later moved to the countryside during my teenage years, the magnetic allure of the now far-off capital become more powerful. It was only after my university studies that I returned to the city for good and started out hoping to find a place called home.

Today, the city is the place where I live but also who I am. London is now a part of my identity, twisting through my DNA like an invisible third spiral of a helix. When I first returned to the city, I began walking around to find out more about the nearby neighbourhoods where I had now moved and then later, as my confidence grew, I ventured further afield. Walking in the city offers particular joys, and a uniquely human scale, and pace, to one’s understanding of it. Crossing from east to west, I would spend the weekend uncovering the stories of the past, first weaving together the historical narratives found in the monuments and architectural wonders; then finding other stories, less well known, that offered new perspectives. Finally, I could construct my own stories as I navigated streets and quarters that were now familiar yet still able to reveal themselves in unexpected ways.

Walking in London led me to think about the people who once were there, and what they left behind. The metropolis I was exploring was an example of the greatest social experiment in human history. People had been making their homes beside the Thames for almost 2,000 years. The study of the past nonetheless forced me to look at the contemporary city in the hope of understanding how it worked, where its genius might lie. I soon found that history alone did not answer the question and that I needed to look at the city in a number of new, different ways, reaching far beyond the archives or library. In addition I found that as I looked around the city, it also changed me.

The anatomy of the city itself is one of the most misunderstood questions of our times. Over the previous centuries, thinkers, architects, scientists and politicians have come up with their own definitions of what is a city. For many, the DNA of the city can be found in its moment of creation and it is through looking at how the first cities were formed that reveals the essential urban characteristics. For others, the city is a physical place and should be measured by its size, volume or shape. Yet, beyond the traditional definitions, perhaps there is a more dynamic way of describing the metropolis. As we face the largest migration in history, in which billions from the countryside will move to the city in the next decades, as well as the innovations in technology that allow us to view and collect more data than ever about the urban world, are we about to change the way we think about the metropolis once more?

Take, for example, two cities, in many ways the opposite of each other: Barcelona in Spain and Houston, Texas. One is an ancient city that has been transformed in the last forty years after decades of neglect; the other is a new metropolis, the fastest-growing conurbation – or network of urban communities – in America. The contrast shows us how difficult it is to define what a city is today, what can make it successful, how we can learn, plan and improve the urban places around us.

In the 1970s Barcelona was in desperate straits following the end of the Franco dictatorship: the ancient city centre had been allowed to rot while suburbs ranged in all directions without planning. The new socialist mayor Pasqual Maragall, elected in 1982, was determined to restore life to the city yet he was restricted on all sides. The medieval core of Barcelona had to be preserved, while the sea to the south and the mountains to the north-east meant that there was little room for expansion; the new city had to be created out of the old, and after winning the right to hold the 1992 Olympic Games a wholesale renovation was heralded under the guidance of urban planner Joan Busquets.

Busquets believed that rather than imposing a bold new vision on the city, the plans should reinforce Barcelona’s existing qualities: as a dense environment, the city should become more dense, and the city centre should become a place that people would want to come to. In effect, Barcelona was forced to shrink in order to become more vital. Much emphasis was put on to regenerating the public and cultural spaces of the city, in particular Las Ramblas, the long spinal thoroughfare that runs from the Gothic quarter to the nineteenth-century Plaça de Catalunya. For a long time this was considered a dangerous, seedy place to avoid but redesigns, pedestrianisation and regular kiosks transformed it into an area that is loved by visitors and locals alike. Barcelona today is one of the most exciting destinations in Europe; its regeneration is a model that has been adopted by many other cities as the template of how to turn a metropolis around.

Houston, Texas, on the other hand, is so successful that it is expanding outwards in all directions; in the last decade over 1 million people have migrated there and have found a new home amongst the 2,000 square miles of sprawl that surround the city. This is an example of sun-belt migration, the middle-class exodus from the north to the warmer south, that is changing America. The movement to Houston alone will represent 80 per cent of the population shift in the US between 2000 and 2030, doubling the city size from 2.1 million to 5 million. Why are so many people moving there?

As Harvard economist Ed Glaeser calculates, while the average middle-class family might earn less than in Manhattan or the Bay Area, the quality of life is much higher in Houston: house prices are cheaper, tax is lower, schools and infrastructure are good, the daily commute is not too arduous. In the end Texans are a surprising 58 per cent better off than New Yorkers, and live in quiet suburban communities with low crime rates, little interference and consistent climate. What is not to like about this scenario? For many it is the definition of a perfect life. As a result Houston will continue to grow, despite the economic downturn.

Both Barcelona and Houston raise questions about the city: will the megapolis grow so vast that it loses its centre, continue to expand without end, making it impossible to see the border between city, suburb, exurb or townscape? Will this endless expansion force us to rethink what a city is? In contrast, Barcelona, heading in the opposite direction, has gained much in return: it is a city for people, filled with inclusive spaces that attract all types of visitors. But how long can it continue with this level of density? Is growth inevitable and what is the social cost of such change?

In order to answer these questions, we need to go back to the origins of what a city is, and how it works.

Why did people ever come together in the first place? We know a surprising amount about the history of cities; it was in the city, after all, that writing and accounting were first invented. Its dimensions have been measured since The Epic of Gilgamesh and since the biblical moment when Joshua circled Jericho seven times in seven days carrying the Ark of the Covenant. But the origins of the first cities are less well known.

The first moment of urban creation is often shrouded in myth. In the biblical tradition, the metropolis was invented by Cain, the murderer, and as a result, according to St Augustine in The City of God, the city of man was for ever cursed by the mark of fratricide. Myths linger over the foundation of other cities: Rome was founded by Romulus who slew his brother Remus, mirroring the biblical story; London was discovered by Brutus, ancient ancestor of Trojan Aeneas, who was sent to Britain by the goddess Diana.

Even in more modern times, the power of the foundation myth is strong. In 2003 the British origins of Calcutta, renamed Kolkata in 2001, were challenged in court and a judge was asked to adjudicate on whether the Indian port had been founded by the East India Company or had, as suggested by the plaintiffs, been a more ancient community as proved by the discovery of archaeological finds at Chandraketugarh nearby. Origins matter.

These legends hide the practicalities of human life. Almost every world city, however, is in fact defined not by its founding kings and mischievous gods but by geography, circumstance and convenience, either as a redoubt against enemies or an advantageous crossing point along trade routes; and in both cases close to sustaining resources. Rome was founded as a natural defence protected by seven hills; London was the most easterly point on the River Thames that could be crossed safely as the Romans arrived from the south coast; Paris, Lagos and Mexico City were all founded on islands protected by the waters surrounding them; Sana’a, the capital of the Yemen, Damascus, Xi’an, one of the four ancient cities of China, despite their inhospitable surroundings, were all born as important staging posts on prosperous caravan routes. The foundation myths also hide another truth: that the first city emerged from a sudden shocking moment in time – the first urban revolution.

Damascus is considered the oldest inhabited city, with a history that stretches to the second millennium bce; founded by Uz, son of Aram. It has been the home to Arameans and Assyrians, conquered by Alexander the Great and then the Romans, the Caliphate, the Mongols and the Mamluks, and later assumed by the Ottoman Empire; finally to be ‘liberated’ by T. E. Lawrence in 1918. Today, once again, the city is on the verge of collapse or a new era. Yet 1,000 years before Damascus was even founded, Uruk, the first city, situated in the deserts of southern Iraq and home to Gilgamesh, already had a population of over 50,000, protected by walls that enclosed an area of 6 square kilometres; now those once great fortifications lie in dust. But where did such settlements come from, if not from myth?

The ruins of Uruk, all that is left of the first city

There is no more powerful image of the city than its relationship with the countryside that surrounds it. This Manichean division between the rural and the urban has shadowed history from the first laments of The Epic of Gilgamesh. We have been taught that the metropolis grew out of the countryside parasitically – the farm became a village, then a town and finally a city. This sequence of events has haunted our impression of the city as a place that leeches blood from the surrounding countryside, draining the life from the nation. The first person to propose this sequence of events was not, however, a Sumerian chronicler, nor a classical philosopher, but the eighteenth-century economist Adam Smith, and few since have challenged his assertion.

But what if – contrary to Smith – the city invented the countryside? Evidence of subsistence farming dates back 9,000 years, long before the first cities, though this does not necessarily explain the rise of the first cities such as Uruk, Jericho, Ji (Beijing), Anatolian Çatalhöyük, Syrian Tell Brak, Mohenjo-daro in modern-day Pakistan, or Teotihuacan, Mexico. We have to rethink our assumptions about the incremental development of cities emerging slowly from smaller settlements, for the birth of the metropolis was anything but gradual. Indeed, rather than emerging out of countryside, the first cities arose despite their surroundings.

As in Uruk, and other early settlements in Mesopotamia, archaeological evidence of the first cities of the Harappan civilisation in the Indus Valley, Pakistan, reveals that a revolution occurred at some point in the third millennium bce. Within less than 300 years a rural community was transformed into an urban power. Archaeologists chart this momentous shift by the sudden emergence of systems of writing, weights and measures; there are also signs of organised town planning and public architecture: ditches, sewers, grids, as well as the development of a distinct style of pottery that suggests a specialisation of skilled labour and a market for goods beyond the basic needs of subsistence.

From these moments of the first urban revolution, cities became something different. The city was born out of trade and developed agricultural sciences such as irrigation and crop selection to support this exchange. Astronomy was developed in order to predict the seasons and support these trading communities. It was the innovations of the city that produced a surplus to feed the citizens who did not work the soil. Urban technology transformed subsistence farming to the extent that workers could leave the fields and work in other forms of industry. ‘It was not agriculture, for all its importance, that was the salient invention, or occurrence if you will, of the Neolithic Age,’ observes the urban writer Jane Jacobs. ‘Rather it was the fact of sustained, interdependent, creative city economies that made possible many new kinds of work, agriculture among them.’1

The metropolis was also defined by its walls that acted as a fortification and a trade barrier as well as, in some cases, a measure of citizenship where belonging was bestowed on those born within. During the Italian Renaissance, the walls of the city state were elaborate and forbidding, displaying both the martial power and the commercial success of the community. Fragments of these walls can still be seen in many of the major cities of the world: from Paris to Marrakech to Beijing. Elsewhere, even when the walls have been dismantled such as in London or Florence, the road scheme still traces the ghostly outline of the old city limits.

And just as the protective walls of the city started to define urban identity, so the spaces within the city itself became divided. Cities have always been places where strangers meet to trade; and storehouses were needed to house the commodities that were exchanged. In addition to the grain, herds and precious luxuries that had been foraged, mined and harvested, the first city was a place filled with workshops where an ordinary object – a bowl, horn or hide – was worked into a desirable product. So cities became places where men who worked with their hands rather than the soil were able to trade for sustenance, exchanging goods for food.

But urban life has always been about more than just survival. As well as trade and work, the first city was also a place of ideas and knowledge. The skills of the artisans gave each neighbourhood a reputation, and in time certain quarters became renowned for their crafts, from ancient pottery to fine carving. It was in the first cities that writing was formulated; initially as a means of accounting, recording property rights and the transactions between traders; then charting the night skies, reading the fortunes of the city in the constellations. Later, writing was used to remember the stories that established the first settlements in myth.

Thus the city was born from a moment of revolution that changed the way people came together and organised themselves. But what did this new social order look like?

The true identity of the city has no single explanation. The historical origins of the metropolis offer some insights into how the city was formed and why, but this does not necessarily tell us how the many parts come together, and what dynamic characteristics make the city so different from everything else. Anyone reading Marco Polo’s description of Cambaluc (Beijing), the great capital of the Khan, gets a sense of the elegance and majesty of the Imperial city, the impressive dimension of the streets and the power of the wealthy who lived behind the palace walls:

It is 24 square miles, since each side is 6 miles long. It is walled around with walls of earth, ten paces thick at bottom, and a height of more than ten paces. There are twelve gates, and over each gate there is a great and handsome palace, so that there are on each side of the square three gates and five palaces; for there is at each angle also a great and handsome palace. In the palaces there are vast halls in which are kept the arms of the city guard.

The streets are so straight and wide that you can see right along them from end to end and from one gate to the other. And up and down the city there are beautiful palaces, and many great and fine inns and fine houses in great numbers. All the plots of ground on which the houses of the city are built are four-square, and laid out with straight lines; all the plots being occupied by great and spacious palaces, with courts and gardens of proportionate size. Each square plot is surrounded by handsome streets for the traffic. Thus the whole city is arranged in squares just like a chessboard.2

Contrast this with a more recent description of Greenwich Village by the local author Jane Jacobs who lived in Hudson Street:

The ballet of a good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and in any one place is always replete with new improvisations . . . Mr Halpert unlocking the laundry’s handcart from its moorings to a cellar door, Joe Cornacchia’s son-in-law stacking out the empty crates from the delicatessen, the barber bringing out his sidewalk folding chair, Mr Goldstein arranging the coils of wire which proclaim the hardware store is open, the wife of the tenement’s supervisor depositing her chunky three-year-old with a toy mandolin on the stoop.

Hudson Street

And so it continues: the lunchtime crowd; the early-evening games of the local teenagers, ‘a time of roller skates and stilts and tricycles, and games in the lee of the stoop with bottle tops and plastic cowboys’; until the end of the day when all that was left was the muffled sounds of parties, singing, the distant siren of the police car. Something is always going on, the ballet is never at a halt, but the general effect is peaceful and the general tenor is leisurely. People who know well such animate city streets will know how it is.3

These are two wholly different visions of what a city is. In Marco Polo’s city, the space is described as grand streets and palaces; the city is its physical form. For Jane Jacobs, there is hardly a word spent on the fabric of the cityscape, which is solely the backdrop for the human drama of urban life. So where do we find the real city: in the fabric of the place or in the bustle of the people who live there?

For centuries bustle has often been the most desperate problem of the city. In the minds of thinkers, planners and politicians, the metropolis, long considered the product of the human intellect, has been seen as a reasonable, ordered and measured place. Just as classical economists have viewed us as rational, uncomplicated movers within the market, so urban planners have hoped that straight streets and building regulations would create efficient neighbourhoods and happy, uncomplicated citizens.

It is time, however, to rethink these basic assumptions. We are not as impartial, linear, self-interested and coldly logical as the equations want us to be, and neither are the places where we live.

The city street is complexity in action. It is not something that can be explained precisely, but we know it when we see it. It is perhaps for this reason that complexity itself has been so difficult to define; one recent attempt unhelpfully stated that a complex system ‘was a system made up of complex systems’.4 But the idea has an unusual origin in the research labs in America during the Second World War, when the conflict brought together many distinguished thinkers to defeat Nazi Germany. This unexpected interaction across the disciplines would have a lasting effect on the way we look at the world; in particular, the interweaving of computing, cryptography, mathematics and missile technology to become the forcing ground of a new kind of science.

In 1948, in an article in American Scientist, Warren Weaver, the head of the Rockefeller Foundation, one of the leading funding bodies in the US, applauded the collaborative nature of the war effort and set out to show that both this and the rise of computing could answer a new set of questions that previously had been ignored.

To this point, he wrote, scientists had focused their attention on two types of exploration: ‘simple’ problems, such as the relationship between the moon and the earth, how a marble rolls down a hill, the elasticity of a spring, based on a minimal set of variables; and ‘disorganised complexity’, problems containing so many variables that it was impossible to calculate the individual characters: the prediction of water molecules in a flowing river; the workings of a telephone exchange or the balance sheet of a life-insurance company. There was, however, a third set of problems: organised complexity. Weaver summed up this new field:

What makes an evening primrose open when it does? Why does salt water fail to satisfy thirst? . . . On what does the price of wheat depend? . . . How can currency be wisely and effectively stabilised? To what extent is it safe to depend on the free interplay of such economic forces as supply and demand? . . . How can one explain the behaviour patterns of an organised group of persons such as a labour union, or a group of manufacturers, or a racial minority? There are clearly many factors involved here, but it is equally obvious that here also something more is needed than the mathematics of averages.5

It needed a man of Warren’s invention (and obsession) to think about life in a different way, and his 1948 paper defined a new path for finding patterns and order within the disorderly. Asking whether one could make connections between a virus, the gene, the rise and fall in the price of wheat, and the behaviour of groups, Weaver answered his own question: ‘They are all problems which involve dealing simultaneously with a sizeable number of factors which are interrelated into an organic whole. They are all, in the language here proposed, problems of organised complexity.’6

Just as Jacobs would later observe on the Manhattan streets, Weaver proposed that under the chaotic surface, an unsighted order or pattern could be found, and that it would take a new kind of science to reduce these strange rhythms into equations. Rather than looking at individual bodies, scientists should study the connections between things, how they related and interacted. Thus he suggested that the world was made up of systems, groups of linked individuals who had a powerful impact on each other. The art of Complexity Theory, therefore, was to work out the original forms of the system and to calculate the particular dynamic that transformed them.

Weaver’s work set out the template of the science of self-organised systems; in time, the ideas opened new avenues of enquiry in biology, technology, physics, cybernetics and chemistry. His fascination with systems became the language expressed in E. O. Wilson’s groundbreaking study of anthills and the development of his socio-biological ideas of the super-organism. Complexity Theory became central to the development of the packet-switch method that underpins the internet. The theory has also been the driving force behind the Black-Scholes algorithm that raised Long-Term Capital Management to the peaks of financial success in the 1990s, and its eventual collapse in 2000; as well as James Lovelock’s theory of the earth as a self-organised structure, Gaia. It has even been used to study the power of social networks as well as an exciting new means to map the brain.

Jane Jacobs was one of the first people to connect the ideas of complexity and the city. She was not an academic, nor an architect, planner or public official; however, her insights into how the city worked, her almost instinctive belief in the complexity of the streets, had far-reaching effects on how cities are made today. In her most famous work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she set out her rallying cry for complex spaces:

Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvellous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order . . . This order is all composed of movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we may fancifully call it the art of the city and liken it to the dance.7

Jacobs called this dance the Ballet of Hudson Street, after her own corner of Greenwich Village. In contradiction of the traditional view of cities as grand boulevards and ordered squares, Jacobs proffers the chaotic streetscape as the genome of the metropolis. The city is a collection of complex spaces, not rational, cold places. This intricate streetscape is perhaps the most important, and forgotten, definition of what is a city, and it is here, in the interactions of the people living their ordinary lives, going about their business and enjoying the variety of the neighbourhood, that the genius of the metropolis can be found. If planners and architects were to pay more attention to the unusual ways that complexity works, and to think more about the life of the street rather than only seeing the empty spaces between buildings, our cities could be very different, perhaps even happier, places.

But the problem with complexity is that it is unpredictable; like an organism, it evolves in unexpected ways. So if we were to put a city into the laboratory what would it look like? The Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas holds many radical opinions on the city. Evolving from his time as a professor in practise of architecture and design at the Graduate School of Design, Harvard, Koolhaas and his team proposed the idea of the programmable city, called the Roman City Operating System (R/OS). As Weaver sets out in his first explorations, a complex system starts with a surprisingly simple collection of things, and thus Koolhaas strips the city to its basic components, ‘standardised parts arranged on a matrix’.8 These initial parts are based on the building blocks of Rome, the ancient city first developed beside the Tiber but which was then translated across the empire and remains today the template of the western metropolis.

Koolhaas is hoping to strip the city down to its basic essentials: the places necessary for a city to thrive. But more than that he wants to show how they transform in unexpected ways once they interact. Like all complex systems, we can define the initial elements but we cannot measure accurately or predict what will happen when they come together. Thus the elements of the city – from arches, temples and aqueducts to basic rules of the grid system and Roman town planning – are divided up and placed within the city space. Once the city has been fully programmed, Koolhaas urges you to press the start button and watch as it proliferates.

From such simple parts, a complex city is quickly born. As the separate parts start to interact, intergrate, correspond and converse, new hybrid spaces are invented, places change shape and characteristics. Some neighbourhoods find an unexpected order while other enclaves live on the edge of chaos. Like a beehive, a termite mound or the petals of a flower, the city generates its own complexity, emerging from within the connections, interactions and networks.

The city is an organism; it has its own special powers; and over time the whole becomes more powerful than the sum of its parts. The complex city cannot be defined by a catalogue of its elements.

Thus to judge a city by its physical fabric alone is a mistake; this is not the genius of the metropolis. Complexity comes from our interactions: we are constantly making connections, moving from place to place, travelling into the office in the morning, making friends and holding business meetings, queuing for a service, picking the children up from school and ferrying them to sports club, or, later that night, enjoying the pleasures that urban life offers, while others clean the office, pick up the coffee mug you left on the desk, drive the subway train that finally takes you home. These connections are important; they formulate the network of the city, they are basic units of energy in the city’s metabolism. As a city grows, so does the intensity of these connections.

But some connections are more important than others, and some work differently from others. Family ties and strong friendships are essential to everyone. The evolutionary thinker Robin Dunbar roughly calculates that most people sustain a close network of up to 150 social relationships. Yet looking at most people’s friends list on Facebook, we have a far larger group of acquaintances, work colleagues, friends of friends. In addition there is the other group of people who we do not often consider part of our social network: people you used to work with but have lost touch; the ex-partner of your partner’s best friend; the sales agent that you see once a year at a conference; the university acquaintance who has just sent a friend’s request on LinkedIn.

These loose connections are called ‘weak links’ and were first formulated by the American sociologist Mark Granovetter. In his groundbreaking study he explored the power of weak ties in the pursuit of finding a new job; he discovered that one was most likely to get a recommendation or a referral from a loose acquaintance rather than a close friend. Weak links, he proposed, offered connections into a wider circle of people and places than those that one sees regularly and live and work in the same places. As he states: ‘Individuals with few weak ties will be deprived of information from distant parts of the social system and will be confined to the provincial news and views of their close friends. This deprivation will not only insulate them from the latest ideas and fashions but may put them in a disadvantaged position in the labour market.’9

It is often assumed that coming into the city from outside one expects a cold shoulder and a resentful shrug: the city excludes outsiders. Poets from Wordsworth to Baudelaire have written of the sensation of being adrift within the city, the anonymity of being in the crowd. The urban myth of the person who was found dead in their apartment long after their passing because no one was a neighbour is an oft-repeated mantra for the inhospitable nature of the city. In addition, the city is a place of such churn and movement it is almost impossible to make meaningful relationships with those around you.

And yet, although this may be an indication that the city is an increasingly atomised space where we lose the traditional connections with family and community, these are not replaced by a meal for one, sat in front of Facebook in a studio flat. Indeed, despite the fact that more and more people are living on their own these days – in New York over a third of the population live by themselves – it is hard to be lonely in the city.

The complexity of the city offers more chances of making connections than anywhere else. In 1938 the Chicago sociologist Louis Wirth published his classic essay, ‘Urbanism as a Way of Life’, as a result of a study of recent Jewish immigrants into the city. He discovered that city life was a threat to culture, that it undermined traditional ties and replaced them with ‘impersonal, superficial, transitory and segmental [relationships]. The reserve, the indifference and the blasé outlook which urbanists manifest in their relationships may thus be regarded as devices for immunising themselves against the personal claims and expectations of others.’

But it is precisely these ‘impersonal, superficial, transitory’ relationships that make the city so unique and important. It is the abundance of these weak ties that brings people to the city, for it is the intensity of these informal relationships that makes the city so special – and it is these weak ties that will hold the mega-city together. In his book Loneliness, evolutionary psychologist John Cacioppo proposes that we are hard-wired to be together and that a sense of loneliness is a warning sign, telling us to make more connections for improved chances of survival rather than an existential condition.

As the mega-city grows around us we are going to have to adapt our connections and relationships accordingly, finding new ways of living together that benefit us all.

The city is built on weak links; it is these moments of human contact that act like electricity for the city. As a result, the city as a whole becomes more powerful than the sum of its parts and this strange phenomenon – which complexity theorists call emergence – means that the complex city offers a unique dynamism. It is also the energy behind the Ballet of Hudson Street and is the raw material from which are developed trust and community despite the strains of urban life.

This energy has a strange power that then feeds back into the fabric of the city itself, and this power is worth examining. Geoffrey West is not your normal theoretical physicist. Educated at Cambridge, he moved to the US and held a number of posts, setting up the high-energy physics group at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. It was while he was there that he become fascinated by the question of metabolism: the relationship between an animal’s size, shape and how much energy it needs to keep going.

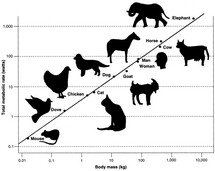

West was inspired by the world of the Swiss botanist Max Kleiber, who in the 1930s studied the relationship of body weight, size and consumption of energy of various animals from a mouse to a cat, an elephant and even a whale. What he found was unexpected, and proved that there was a direct link, a scaling law, between the size of the beast and its energy usage. It also shows that a larger animal is likely to live longer than a small one: for while most animals die at between 1–2 billion heartbeats, a chicken heart beats 300 times a minute, an elephant’s only 30 times. Kleiber found a direct relationship between size and life expectation. In his research West refined Kleiber’s original laws and attempted to find out why they worked.

In 2005 West was named president of the Santa Fe Institute, the mecca of study in Complexity Theory, set up in the 1980s to explore the connections between physics, mathematics, computation and evolutionary biology (the institute is so multidisciplinary that even the novelist Cormac McCarthy has a desk in the facility). There, West turned his focus on the nature of cities, perhaps the greatest self-organising organism of all; the results would gain him the honour of being named one of Time magazine’s ‘100 Most Influential People in the World’.

Klieber’s diagram shows the relationship between size and metabolism

West studied how cities developed dynamically as they grew in size: how they changed shape and personality, how interactions intensified with increased levels of density. As he later admitted in an interview: ‘We spend all this time thinking about cities in terms of their local details, their restaurants and museums and weather . . . I had this hunch that there was something more, that every city was also shaped by a set of hidden laws.’10

He was determined to find the rules governing the complexity of the city. Already he understood something of the nature of self-organised systems, but he gave it a twist by considering the city as an organic whole, as one might think of a beehive, or an anthill, or even an elephant.

Thus he gathered together as much data as he could – measurements of scale of urban centres in the US over 50,000 citizens; statistics on gross metropolitan product; crime figures; the amount of money made from each petrol station in all fifty-two states; patents as well as tax returns – and put them all together to find the underlying order of how the city worked. The study did not just cover American cities but also included data from the National Bureau of Statistics in China, from Eurostat, even measurements of road surfaces from across Germany. Combined, the information formed one of the most powerful data sets imagined. What West discovered, however, was even more exciting.

In a ‘unified theory of urban living’, West proposed, all cities are the same and all follow the same rules. Therefore, while we can see individual cities as having their own particular history and personality, underlying rules apply and prove that they have more in common with each other than not. In addition, just as the metabolism of a mouse has some connection to the metabolism of a whale, so size is the major determinant of the character of a city. In effect, tell West the population figure for any city and he can give you the basic characteristics of the place: ‘I can take these laws and make precise predictions about the number of violent crimes and the surface area of roads in a city in Japan with 200,000 people. I don’t know anything about this city or even where it is or its history, but I can tell you all about it.’11

Yet while you can calculate the urban metabolism just as you can that of an elephant, in another way cities are very different from animals. Klieber’s original law of energy consumption worked on a sublinear quarter-rule, so that the metabolic rate does not correspond exactly to an increase in body size. Rather than the metabolic rate increasing by 100 per cent whenever the animal doubles in size, it follows a ‘sublinear’ path and increases by only 75 per cent.

The city, on the other hand, follows a similar ‘superlinear’ power law, so that every time it doubles in size, it increases its efficiency and energy use. West’s results can be seen across the board: moving to a city that is twice the size will increase per capita income, it will also be a more creative and industrious place; as the pace of all socio-economic activity accelerates, this leads to higher productivity while economic and social activities diversify.12 The increased complexity that comes from the agglomeration that one finds in the city, therefore, is what makes cities special.

As West said in a 2010 interview with the New York Times, he offers a scientific bedrock to Jane Jacobs’s imaginative hunch: ‘One of my favourite compliments is when people come up to me and say, “You have done what Jane Jacobs would have done, if only she could do mathematics” . . . What the data clearly shows, and what she was clever enough to anticipate, is that when people come together, they become much more productive.’13 While Jacobs focused her attention on her own front stoop and observed life on her local street, West’s superlinear power law shows how this complexity is applicable wherever people gather.

The city of the twenty-first century will not be a rational or ordered place; the world city will more likely resemble the chaotic lives of the hundreds of thousands who have just arrived and are looking for a home. It will be a dynamic place of transition and transformation, discovering for itself the underlying laws of how it works. It is perhaps only West’s ‘unified theory of urban living’ that will survive the social, economic and political upheavals of the coming decades. This is both an exciting and disquieting possibility. Yet there are also very good reasons to be hopeful. And this hope comes from choosing to think about the people, not places, of the city: how they live, work, play and behave.