10

HOW MANY LIGHTBULBS DOES IT TAKE TO CHANGE A CITY?

Standing on the crest of the hill, it was strange to think that I was, officially at least, in the centre of the city. The wind was still and the temperature unseasonably hot; a heat shimmer softened the edge of everything. I looked northwards across virgin wetlands where a creek meandered lazily through the landscape, backed by a solid band of verdant woodland. There was almost no sign of human habitation until I peered up towards the horizon and saw the famous skyline of downtown Manhattan. The new World Trade Tower rose into the air behind the skyscraping castellations of the cityscape.

I was standing on the North Mound of the Fresh Kills landfill site, my view towards the city 14 miles away contrasted with what appeared to be a completely untouched landscape. The site is named after the creeks and wetlands, the ‘kills’, which in the 1950s were considered to be wasteland rather than a natural habitat. Yet I was on top of 150 million tonnes of garbage, the collected detritus of nearly fifty years of the city’s waste that had been gathered, put on barges, shoved into trucks and dumped into what was once the largest landfill site in the world: rotting food, plastic bags and kitchen waste, packaging, discarded newspapers and broken goods – everything the city threw away.

After 9/11 it was here, on the West Mound, across from where I was standing, that 1.4 million tonnes of twisted metal, crushed cars and mountains of rubble from the collapse of the Twin Towers were transported so that government agents in white jumpsuits could comb the material for evidence, while families who had lost relatives in the attack could come and hope to recover some meagre memorial to record their loss.

Now it seemed like nature had reclaimed the landscape. There was an osprey nest by the creek and there had even been reports of a coyote. As I stood there, I watched a butterfly flit between the poppies and the meadow flowers that had clustered and grown across the mound. I was told that other water birds had returned, as well as foxes and vultures, and that rather than using petrol-powered lawn mowers to maintain the grass, a herd of goats kept the meadow at a manageable length. If I did not know it, I would have thought that I was on a heath that had been left for decades, not a project designed to restore the blighted landscape and which had only been started in 2003. The only reminder of where I was were the towers in the far distance, like the Emerald City of Oz, and a sequence of taps and pipes sticking out from the top of the mound which were used to siphon off the methane and leachate that came off the waste only a few feet down.

The view from the North Mound, Fresh Kills, with Manhattan in the distance

Fresh Kills was first opened in 1947, one of Robert Moses’s grand schemes for the improvement of the city. It was meant to be a temporary landfill, used for no more than three years, but after the infrastructure and the disposal systems had been put in place, delivering 29,000 tonnes of waste a day, it was decided that this corner of Staten Island was far enough away from Manhattan for the problem to be out of sight and out of mind, and it remained a permanent dumping ground. From then on the islanders had to endure not just the smell, and the swarm of seagulls that circled the trash mountain, but also the indignity of being the refuse tip for the rest of the five boroughs. Every year there were complaints that the Island was getting the foul end of the bargain. By the 1990s, the rubbish had formed into four vast heaps on either side of the once marshy creek where barges came in and out, every day dropping off their odorous load. In addition, the community was growing, its housing moving ever closer to the fenced edge of the depot. The site was closed in 1997 and the newest housing developments now abut its perimeter with rows of neat, white suburban homes.

What are we to do with places like Fresh Kills? It is in the city – its noxious, polluted air, the lack of green space, the mountains of trash – that the questions of climate change, waste and quality of life are most clearly delineated and most urgent. One does not need to see pictures of the garbage from Fresh Kills, or be reminded of the recycling factories of Dharavi, or measure the level of toxins in the air at a particularly busy crossroads to be reminded of the everyday hazards of urban living. It is calculated that millions die every year, even in the most dedicated of clean cities, from respiratory disease. We can now measure carbon emissions at every street corner and count the millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases that rise from the urban landscape. The city today may no longer look like the sooty industrial hell of Friedrich Engels’s Manchester but this has only disguised its poisons. And yet, for all this, the city might also be the place with the greatest potential to answer the age’s most pressing issue.

The story of what was done at Fresh Kills – which was eventually transformed into the verdant landscape I found myself standing upon on my trip to New York – is the story of a successful large-scale government project that should make people think about the city in different ways. The site was finally closed after political pressure had prevailed to make each of the five boroughs deal with their own waste rather than dumping the lot on Staten Island. After that it was decided that Fresh Kills was to be capped and then turned into parkland and a nature reserve. However, the process of the transition itself shows how complicated such operations can be.

The first stage of the project was overseen by the New York Department of City Planning which, in 2001, launched an international landscape-design competition. At the same time, the process of treating the ground and making sure that the waste was safely capped was placed in the hands of the Department of Sanitation, itself split into two sections – maintenance and solid waste – which did not always agree on either methods or outcomes. The NYDoS was also charged with overseeing the continuing maintenance of the gas and leachate that must be processed onsite. In 2011 this provided $12 million’s worth of natural gas that was then sold on the local market; while the leachate was treated and cleaned, creating fresh water. The ground, once it had been capped with an impermeable layer of plastic, was spread with high-grade soil – in places even better soil than can be found in Central Park – and left for five years as it settled. It was then handed over to the New York Department of Parks and Recreation, which remains in control of planting and cultivating the parkland and its ecology.

The NYDoPR had to follow strict rules about soil usage and design. It also had to respond to the semi-natural environment that had been created. The impermeable cap, which made any leakage through the skin impossible, changed the way the normal landscape operated: it meant that rainwater ran off at a faster rate than elsewhere because it could not soak down to the water table. As a result the ground had to be sculpted with run-off in mind. In addition, a team from Pratt College conducted a study to establish whether tree roots could pierce the cap. There were disputes between the two sections of the Department of Sanitation over how high the grass should be allowed to grow, as well as questions about where the seeds for the wild flowers should be cultivated, leading to the creation of a seed bank on site.

The 2001 competition called for designs from five of the world’s leading landscape architects and was won by James Corner Field Operations, a company run by the Manchester-born James Corner who, at the time, was a professor at Pennsylvania University with an office consisting of only three people. The Fresh Kills site was bigger than anything else built in New York’s history: a space within the city limits that was three times the size of Central Park. Corner produced a masterplan in 2003 that was then shared with ‘agencies, stakeholders and [the] community’ as well as conducting a series of more formal environmental-impact studies and departmental reviews. The plan was bold in every way, imagining a process spanning to 2040 and placing a priority on community participation at all stages. This would have repercussions on the speed at which things could be achieved, but all parties felt that this was a worthwhile price to pay.

The site was to be split into five regions: the four mounds, south, north, east and west, and ‘the confluence’ in between that ran along both sides of the creek and tidal flats. By 2006 work had been completed on the caps for the North and South Mounds and by 2011 it was underway on the East Mound. While the western limit looks like a grown-over, natural landscape, it is still awaiting treatment that will begin in the next few years. The confluence will provide a centrepoint within the four mounds, a space for educational facilities, services, cafés and retail outlets for the expected visitors who will soon be arriving to enjoy a touch of nature within the boundaries of the five boroughs. The Fresh Kills Park Conservancy was founded in 2012 to oversee the management of the area and plans are already in place for wind-powered cafés, zero-carbon energy and green toilets.

Yet, as with all big government projects, Fresh Kills is susceptible to politics and budgets. The original tally was $200 million but has now been reduced to $112 million following the economic downturn. This has not derailed the project, however; rather it has been spread out over a longer timeframe with the hope that each new budget period might see a change in fortunes. For, despite the bureaucratic, interdepartmental headaches, everyone involved so far still feels that the park will be an essential part of the future of New York. It is certainly far more than an election-winning photo opportunity – but what will its real impact be on the city?

Visiting the offices of James Corner Field Operations, situated just north of the High Line, which was also designed by Corner, one is immediately struck by the atmosphere of a successful architectural practice: there is complete silence as rows of young people look intently into their Apple screens, and yet there is a sense of furious activity and concentration. Meeting Tatiana Choulik, who has been working on Fresh Kills since the beginning, highlighted the fact that the role of the landscape architect was to do more than encourage the land to return to some perceived idea of wilderness. She explained that Corner’s aim is to create a certain kind of landscape that promises more than wasteland: a place, like the High Line, that offers those rare moments in the city where one is allowed to be in contact with something natural. And it is important that these places are socially inclusive, and yet are allowed to evolve. This philosophy is encapsulated in Corner’s concept of ‘lifescape’: ‘an ecological process of environmental reclamation and renewal on a vast scale, recovering not only the health and biodiversity of ecosystems across the site, but also the spirit and imagination of people who will use the new park’.1

As I stood on top of the North Mound, and looked across towards the outline of Manhattan, I was hugely impressed by what had been done already. I felt sure that in time people from the city would go there to enjoy the scenery and the wildlife, and – for some – it would be their first real encounter with the countryside. Yet I wondered whether this would change the way they think about how they live back home in the city. When they visit they will be walking up mounds of their own rubbish, but will it make them think about how they dispose of this refuse in the future? Only a few hundred yards away, I could see the waste plant that still processed Staten Island’s garbage, and there also were the barges that took the material further away to North Carolina for disposal. Would that river traffic ever cease or would we just become better at sending our garbage further out of mind? Can we ever get away from the fact that the city is an environmental crime scene? If we are being honest with ourselves, are large-scale projects like Fresh Kills little more than gestures with few provable positive outcomes?

The debate on the sustainable city is happening now: from international government conferences like Rio+20 in June 2012 to local campaigns to encourage people to recycle or compost, the imperative to clean up our urban lives can no longer be ignored. Yet what is the most effective way to make real change happen? Expensive exercises like inter-governmental conferences may bring together the most powerful people on the planet to make promises and discuss solutions, but they are going to have little impact unless they have some influence on the everyday behaviour of individuals, and vice versa.

At the same time, mayors are trying to think about if and how to alter the fabric and infrastructure of their cities to reduce carbon emissions: creating new standards for housing; finding technologies for public transport that reduce harmful gases; devising waste-management strategies to deal with our rubbish in a more responsible way, whilst also encouraging changes in the behaviour of the ordinary citizen: persuading people to rethink the way they travel, consume and live. Pushing from the other direction are the people themselves, who are justifiably unhappy with the slow rate of change, infuriated by the blind spots of national policy, driven by the fear that we have all left it too late, and that putting profit first will always scupper any chance of a safe future.

If we can understand better and enhance the advantages of urban living, as well as agreeing on ways to improve the sustainability of life in the city, then we might just survive. It may appear counterintuitive but the city could be our ark, rather than our coffin.

Part of this process begins with realising that living in the city actually offers a far greener way of life than is commonly imagined. Until recently many environmental thinkers and campaigners presumed that the city – the place where there were the most people, the most waste, and the most energy usage – was unnatural and ecologically dangerous. Its air was thick with pollution; it was a breeding ground for disease; the demand for water and food in places where there were no reservoirs or fields made the transportation of life’s necessities a logistical suicide note. They saw the city as a centre of wanton consumption that never gave anything back.

This image of the concrete jungle was held up as a stark contrast to the homely view of the bucolic smallholding deep within nature. And the statistics seemed to support their view: cities hold over 50 per cent of the world’s population, but take up less than 3 per cent of the planet’s surface; they consume nearly 80 per cent of all our energy. How can living in the city possibly make you greener?

As I travelled by bus from the Fresh Kill site towards the Staten Island ferry depot that would take me across the water to Manhattan, I had to remind myself that I was still within the heart of New York itself. My journey began in semi-rural quiet and as I headed north the houses began to cluster together. Soon a street of houses, surrounded by green yards, was replaced by homes with a front garden, only enough space for a car and a small lawn. By the time we reached the ferry port the suburban buildings had been substituted by urban streets, tightly packed with shops facing out onto busy pavements; blocks of flats and tenements rose above them into the sky. Once on the ferry, having made my way to the front of the boat, I watched with wonder as we approached Manhattan, a scene that will never cease to be impressive. In only a few kilometres I had travelled from the quiet periphery to the very heart of the urban world, and with each step my environment was becoming increasingly dense: green space squeezed out and replaced by concrete, asphalt and brick.

Yet in 2009, the journalist David Owen revealed the astonishing truth that living in New York is a more environmentally friendly lifestyle than living in the suburbs or even the countryside. He showed that, contrary to most assumptions, when people live in close proximity to each other, in a walkable environment, they actually become far more environmentally efficient. Despite the heavy energy usage and the costs of transportation within the city, it is nonetheless a remarkably smart way of gathering people together. For example, per square foot New York generates more greenhouse gases, uses more energy and produces more waste than any other place in America of a comparable size; however, New Yorkers individually are actually more energy efficient, emit less carbon and produce less waste than the average person outside the city.

In 2010 New York as a whole emitted 54.3 million tonnes of carbon. Some 75 per cent of this came from buildings, 21 per cent from transportation, 3 per cent from solid waste, 2 per cent from waste water and 0.1 per cent from streetlight and traffic signals. In total, 96 per cent came from burning fossil fuels. In New York, the energy use of an average household is 4,696 kilowatt hours per year. This is a difficult figure to understand; it sounds huge and it is certainly larger than most European cities – and definitely greater than any Chinese or Indian family – but it is small compared to sprawling Dallas, where a household uses 16,116 kilowatt hours a year. Similarly, although New York emits 1 per cent of all the greenhouse gases of the US (which taken as a single figure seems enormous), this figure is incredibly efficient when you take into account the fact that the city contains 2.7 per cent of the entire population.

One way to explain this unexpected efficiency is to return to Geoffrey West’s model for the metabolism of the city. As he showed, when a city doubles in size, there is a scaling of efficiencies. This means that as more people come to live in the metropolis they share services and resources; thus as a city doubles in population size, it only needs to increase its carbon footprint by 85 per cent, including everything from heating and housing to the number of petrol stations; representing an energy saving of 15 per cent. As the metropolis grows it becomes more energy efficient, not less. Indeed, in one interview Geoffrey West went so far as to state: ‘The secret to creating a more environmentally sustainable society is making our cities bigger. We need more metropolises.’2

Yet, once again, it also matters what kind of city that you live in. New York is a very different city from, say, Houston. While the average New Yorker emits 6.5 metric tonnes of carbon a year, the Texan produces a staggering 15.5 tonnes. Why is there such a vast difference? Firstly, in Manhattan people are forced to live close to each other and on top of each other, while in Texas there is no limit to the expansion of the city, and therefore everyone can have their own home in the suburbs with their SUVs parked outside.

Even within a city like New York or San Francisco, however, there is also a difference of environmental outcomes, depending on where you live. There is a cost in choosing between living in suburbia and enjoying the advantages of the inner city. Transport and housing takes up approximately 40 per cent of all household energy use in the US (about 8 per cent of all world carbon emissions). In both cases it is more energy efficient to live in the city than the suburbs.

Inner-city dwellers take up less space. Since the Second World War, the average American home has doubled in size, creating vast houses or apartments that are often empty yet are still being heated, with the lights left on and the televisions on standby. In contrast, apartments and homes in San Francisco have shrunk. It is also far more efficient to heat a block of flats than it is to heat a suburban house. In a study from the 1980s, it was calculated that an ordinary Bay Area apartment block used 80 per cent less fuel to heat itself than a new tract house of the same size in Davis, California, 70 miles away. This is because each apartment insulates and heats the apartments on either side. In addition, each dwelling is less exposed to the outside and therefore less likely to lose heat through windows. Finally the roof itself will create a smaller ‘heat island’ effect for the number of people in the building.

Secondly, stacking people close together creates the kind of community that promotes Jane Jacobs’s ballet of the street. In New York, only 54 per cent of householders have a car and within Manhattan they use only 90 gallons of gasoline a year. By contrast, Houston has been built around the car, with over 1,100 miles of freeway to take the suburbanite from his idyll into the centre of the city. It is calculated that 71.7 per cent of all journeys in the metropolis are taken by single drivers on their way to the office, and as a result those drivers are likely to sit in 58 hours of traffic every year. In the clearest indication of the difference between living in the centre of the city or the suburbs, the economists Ed Glaesar and Matthew Kahn calculated the costs for heating and travel between each neighbourhood: they found that the average suburban New Yorker uses $289 more energy a year than their inner-city counterparts just to get around and heat their homes.3

The reason people do not use their cars in the city is obvious: in a dense city everything is on your doorstep. You are more likely to walk to the convenience store than jump into the car. In addition, the cost of running a car is becoming prohibitive. In both America and Europe there has recently been a decline in car usage by 18–29 year olds. Between 2000 and 2009, the average vehicle miles travelled by this age group dropped by 23 per cent, and the number of young people who do not have driver’s licences has risen to 26 per cent.4 With improvements in bike lanes as well as public transport, more people are leaving their cars at home, or even at the dealership, when they travel into the city. In addition, as the promotion of more walkable cities gains momentum, they are also preferring to use the pavements, thus adding to the ballet of the streets.

But this is not enough. Despite the advantages of urban living, we are still using too much energy, spewing out an unsustainable level of carbon emissions. We are producing too much waste, our cities create ‘heat islands’ that raise the atmospheric temperature, the materials – bricks, steel, plastic, glass – we use to build our houses and our streets are inefficient. Cities are centres of consumption and goods from around the world are transported there to obtain the best prices; at a time of scarcity, water and food are brought long distances to keep the metropolis fed and alive.

The city is already under threat from the damage we have inflicted upon the environment in previous centuries. According to Matthew Kahn, the change in climate will affect many of our major cities and will have very serious consequences: as the polar ice cap melts, coastal settlements will become the first to suffer. San Francisco, London, Rio and New York will all be affected as the water rises and swamps the lower-lying (and often the poorest) communities. For example, San Diego in Southern California will be particularly hit: by 2050 the sea level will be approximately 12–18 inches higher and the temperature will have risen by an estimated 4.5º F. Meanwhile the city will have continued to grow, bringing with it an increased demand for services such as water. However, despite rising sea levels, at the same time the Colorado River will dry up; there will also be a greater threat of wildfires in the hot, dry hinterlands. Kahn predicts that while the population of San Diego becomes increasingly elderly – as the average age of citizens grows and the young will have more of a chance to leave when the threat approaches – it will be society’s most vulnerable that will be on the front line as the waters rise.

Yet it is possible to prepare for this, Kahn tells us. We can move to the burgeoning sun-belt cities where flooding is less of a risk. And we can build defences against the rising tides, which are expensive but worthwhile: the Thames Barrier, for example, which spans the river to the east of London, was erected in response to a flood in 1953 that submerged Canvey Island in Essex and killed 58 people. Since its completion in 1984, the frequent raising of the barrier in emergencies has increased: in the 1980s, it was raised only four times; this went up to thirty-five in the 1990s, and has more than doubled to seventy-five in the last decade. More worryingly, engineers now estimate that the current barrier will only last until 2060. Plans for its replacement to deal with increased flooding are underway.

But such forethought is rare. Too often, as was seen in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, it is only after the disaster that essential preventative measures are put into place. As Katrina also shows, it is a damning indictment of the city authorities that the lion’s share of protection and preparation were focused on the preservation of the richer neighbourhoods, while the most vulnerable were left to fend for themselves. Thus, whilst an environmental disaster can have a calamitous effect on a whole community, the way the damage falls out across neighbourhoods is defined by society’s choices.

So what is to be done? Kahn suggests that the market will correct itself and provide the answer: that innovation and people’s sense of self-preservation will ensure that we face the dilemma of climate change and triumph, just as we have done so often before throughout history. In this reading of disaster economics, Kahn proposes that ‘what does not kill us will make us stronger’.5 But it is not a convincing argument: we cannot base the survival of the planet on the trickledown effect. We are going to have to make rather more concrete plans for the future.

Perhaps we should start again and build our cities from scratch? Masdar City is currently being built by the Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company, designed by the leading architect Norman Foster, in the desert. Foster’s career has always been about pushing the boundaries of architecture, having as a young man been deeply influenced by the American designer Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic dome (famously designed on a massive scale as a protection for the city) was a shining example of ‘doing more with less’. With iconic commissions such as the HSBC Bank in Hong Kong, the Gherkin (30 St Mary Axe) in London, and the truly impressive Beijing Airport, Foster has been at the forefront of finding a technical solution to questions of sustainability, investing in new materials, working on designs that reduce energy use, and always remaining visually innovative.

Breaking the ground at Masdar

The architect’s model for the zero-carbon city

At Masdar Foster takes the idea of the sustainable city to its current limits. He began his quest by studying traditional Arabic building methods to understand how societies had grown up and thrived in such a hostile environment. To this he added a lifetime’s passion for the latest technologies and materials. Built upon a raised 23-foot-high base, the projected city was designed to benefit from desert breezes, creating a natural cooling system. One of the most futuristic ideas that Foster developed in his prototype was the replacement of all cars by personal rapid transport (PRT), pods that run along rails through the underground level of the city. This allowed for a tighter street grid, which once again helps to keep the ground level shady and cooler.

The whole project is intended to be as ‘zero carbon’ as possible, and a 45-foot Teflon-coated wind tower situated in the centre of the city will display how much energy the community is using. For as Fred Moavenzadah, head of the Masdar Institute, which was one of the first buildings to be constructed in the city and opened in 2012, points out, this is an experiment in futuristic design – the smart eco-city – but it also has a human element. Despite the fact that all photos of the site currently have few people in them, this will be home to 50,000 residents and 40,000 commuters who will leave their air-conditioned cars at the city boundaries. Once inside they will be forced to adapt to a more sustainable lifestyle: ‘We are living and experiencing what we are trying to . . . educate people about . . . We’re using roughly half the energy of a normal building of this size. We are producing no carbon because it’s all renewable. Our water consumption is less and our waste generation is relatively low.’6

Masdar is an example of the new eco-cities that herald the possible future of urban living. It is ironic, however, that Masdar is only a few miles from the oil fields of Abu Dhabi that paid for the experiment. In fact, while funding the project, the Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company is also actively searching for new oil ventures in Oman and Libya as well as south-east Asia.

China, also, has invested in engineering new eco-cities. Despite its reputation as a dirty industrial economy, developing polluted and congested cities at an alarming rate, China is also the largest investor in green technologies. In 2007 the government bought 35 million solar water heaters – more than the rest of the world combined. They will soon be leading the way in wind energy. Already China can boast ten eco-cities and eco-regions: new settlements outside Beijing and Shanghai, Chongqing, Guiyang, Ningbo, Hebei, Tongling, Liaoning, Shandong and Jiangsu.

Yet these eco-cities perhaps promise more than they can deliver. An engineer’s solution looks very comprehensive in their brochures and the media is keen to report the projected figures before the projects are even off the ground but, like the images of Masdar, the numbers do not tell the human story. The eco-city without people voluntarily living more responsible lives is just an exercise in gadgetry and political gestures.

For example, there was a big celebration when the new Sino-Singapore city of Tianjin Eco was opened in spring 2012, just an hour by train from the centre of smog-bound Beijing. The new city was built in three years on top of abandoned salt pans, alongside an already existing industrial city, old Tianjin, which had gained a reputation as China’s centre for innovation and hi-tech industries (enticing companies like Airbus, Motorola and Rockefeller to set up branches there). The eco-city was so well designed that, according to one report, ‘the residents will not be expected to make any particular effort to be green’.7

Yet, as architecture critic Austin Williams points out, there is a huge divide between the publicity and the reality. Tianjin places transport at the heart of sustainability, promising that 90 per cent of all journeys will be on public transit. The city promises that carbon emissions will be reduced to 150 tonnes per $1 million of GDP. In ten years’ time, the aim is for each person to use a maximum of 120 litres of water a day. Finally, 12 square metres of green space has been reserved for each citizen. This all sounds impressive until you compare it with an existing city like London. In each case, Tianjin is promising a new future that has already been achieved. In London, over 50 per cent of all trips are already on public transit; London produces only 99 tonnes of carbon for every $1 million of GDP; each Londoner already only consumes 120 litres of water a day without regulation; and there is a staggering 105 square metres of green space for every citizen.8

In another instance, the rise and fall of the much-heralded eco-city of Dongtan is a cautionary tale. Launched in 2008 with a huge publicity campaign and backed by both Prime Minister Tony Blair and President Hu Jintao, Dongtan was to be the project from which all other plans would draw inspiration. Located on Chongming Island, Shanghai, it was to be completed in time for the 2010 Shanghai Expo, and it was the paradigm of east-meets-west green development.

Except that it never happened: by 2009, the farmers and peasants had been removed from the land and a visitors’ centre had been built. By the time of the Expo, the local party leader Chen Liangyu was in prison for bribery, most of the contracts had lapsed, and the technology companies were finding it difficult to adapt their innovations to the situation on the ground. Nevertheless, the world’s media continued to lap up the computer-generated images of the perfect society. Eventually, the project fell off the partners’ roster of current projects and the visitors’ centre was closed. As Dongtan was mothballed, the farmers themselves who had invested their life’s savings in the project – and who had agreed to be moved from their homes – were hung out to dry.

Even if we can rely on the innovation of planners, engineers and visionary architects to deliver the brand-new eco-city, built from scratch out of the dust and desert, this is not a practical future for the majority of the world. The costs are prohibitive: in the face of the global downturn repeated cuts have been made to the construction site at Masdar, as certain projects no longer make economic sense. Thus, initially the settlement was to be built on a vast platform that allowed the desert air to circulate and cool the whole city as well as create an underground layer in which to place all the infrastructure and transport including the eye-catching PRT system. But this was cancelled when the overall costs were reduced from $22 billion to $16 billion.

The biggest obstacle to greening our cities is the fact that most of us already live inside them; so how can we make the places where we live now greener and better prepared for the future? Must we rely on an engineering solution, developing greener ways of living by design? What role will our mayor and politicians play in bringing greener infrastructure to the city? And above all, what do we need to do ourselves to ensure that the way we go about our lives improves the places in which we live?

As recent climate-change summits – such as Kyoto, Copenhagen and Rio+20 – have shown, the level of trust between nations to put environmental standards before profit is very low. It will be cities therefore, rather than nations, which will be at the forefront of the climate-change challenge, driving initiatives, setting out practical policies and ensuring that they are followed through; but the individual city authorities will only get things done with the collaboration of grass-roots active citizens.

The C40 group was created in 2005 as a union of the leading cities of the world to combat the challenges of climate change, and to share ideas and policies on how best to reduce emissions, and find design solutions for the city of the future. Each city within the group has now published goals and projections for improving carbon emissions: Buenos Aires aims to reduce emissions by a third by 2030; Chicago hopes to reduce them by 80 per cent by 2050; Madrid will halve its emissions by 2050; Tokyo promises to cut them by 25 per cent by 2020. In addition to carbon emissions, the C40 group has highlighted eight key areas to prioritise – building, energy, lighting, ports, renewables, transport, waste and water – and they are asking for radical solutions.

So far, responses have been diverse; for example, San Francisco has begun planning the largest city-owned solar-power station in the world; Oslo, Norway, has pledged 10,000 intelligent street lamps that will reduce energy consumption by 70 per cent and save 1,440 tonnes of CO2. In Emfuleni, South Africa, they are installing a city-wide water-efficiency system that reduces the pressure within the network thereby reducing costly leakages. This is proof, at least, that city governments acknowledge the issues and are starting to search for interesting solutions regardless of national policy. But there is no single solution for every city; every metropolis faces its own problems.

In 2007 Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the PlaNYC, with the promise ‘to prepare the city for one million more residents, strengthen our economy, combat climate change, and enhance the quality of life for all New Yorkers’.9 The plan brought together twenty-five city agencies in order to set a focused agenda for the five boroughs that would cover every aspect of New York, from housing, parks, water, waste and air quality, to how to remain competitive within the global market. At its launch there were 127 proposed initiatives, and by 2009 almost two-thirds had been achieved.

Some examples of the projects illustrate the realities of dreaming the green city, retrofitting the existing urban framework rather than building from scratch. Balancing the new with the need to renovate and maintain much of the city’s fabric, 64,000 housing units have been constructed or redeveloped in line with a fresh set of green building codes, which outline energy use, materials and emission limits. In addition, 87 per cent of these units can boast easy access to public transport. There was also a concerted effort to build more parks so that 250,000 more people were no less than a ten-minute walk away from a green spot. Over half a million trees were planted. There was a $2.1 billion project, Water for the Future, designed to clean up the waterways. There was also a promise to double waste recycling to 30 per cent of all garbage by 2017, and the city is currently on track to reduce carbon emissions by 30 per cent by the same year.

Transport is responsible for at least 25 per cent of all of New York’s emissions. But there have been huge advances in making public transport more efficient and encouraging people to use both the subway and buses. In addition, the transfer of the traditional yellow cabs to green fuel is moving apace, with 30 per cent of the total fleet running on biofuels. A new fleet of 18,000 apple-green cabs – Boro Taxis – will be able to pick up passengers outside Manhattan.

There have also been attempts to combat congestion. Mayor Bloomberg first announced in 2007 that he would promote congestion charging and the news was welcomed by many groups, businesses and residents on the island. Reports were written, feasability tests made, proposals put forward for an $8 levy to be raised on any private vehicle, and a map was drawn up introducing a cordon across South Manhattan between 6 am and 6 pm on weekdays. However, in the following years negotiations with the city council and then the state assembly became more complicated, as objections were raised by Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx as well as the state beyond the city. In the end it seemed that not even congested New York was willing to penalise the motorist.

But the proposal is not completely shelved. In March 2012 Sam Schwartz, former first deputy transportation commissioner of the New York City Department of Transportation, announced that he had independently been working on a plan that would integrate congestion charging and a system of tolls that would ring the city, with the less than snappy title ‘A More Equitable Transportation Formula for the NY Metro Area’. His proposal would reduce traffic dramatically as well as make $1.2 billion a year for the indebted Metropolitan Transportation Authority and provide 35,000 locals with jobs. The scheme was structured around congestion – as befitting the man who invented the word ‘gridlock’ – rather than sustainability, but nonetheless it seems a powerful incentive for getting cars off the road. It is also designed to use existing infrastructure more efficiently, applying higher pricing where there is most congestion and where public transit is available. The plan was highly praised throughout the media because it spread the burden across Manhattanites as well as those who were travelling to the island. The proposals have not yet been adopted by City Hall, but they keep alive the hope that congestion charging could be one useful method to green the city.

One of the more unusual proposals in Schwartz’s plan was the creation of special bike and pedestrian bridges to further encourage cycle use in the city. By summer 2012, bike numbers had doubled over the previous five years. Safety is an important factor in encouraging people to commute on two wheels, and statistics show that crash rates have declined by 71 per cent between 2000 and 2010. The widespread bike-lane network that has been added to the city’s road system over the last decade has certainly helped, with 288 miles of lanes – 185 miles exclusively for bikes – designated throughout the five boroughs.10

This has not occurred without campaigners and activists such as Transport Alternatives pushing City Hall to address the problems of roads, bike lanes and safety. Founded in 1973, this group has been constant in promoting bicycling as the most sustainable way of getting around the city, but this has also led to discussions of efficient public transport, as well as promoting liveable streets for all. As their website says, it is more than just the bike: ‘The most perfect street we can imagine is one in which a child can safely play and regularly has the space to do so. With streets and sidewalks 80 per cent of New York City’s public space, Transportation Alternatives works with individual communities to make those spaces and local streets safe for all.’11 The greener neighbourhood is, in their opinion, a more pleasant, human place to live.

This increase in bike usage has had an unexpected knock-on effect in the city. With so many people now riding into town, they need somewhere to put their bikes and parking bars are becoming increasingly scarce. As a consequence, some offices are now providing storage spaces, with the New York Times reporting ‘more and more this is a selling point for the real-estate industry’,12 and ‘bike rooms’ are awarded extra points according to the LEED sustainability award scheme. The transport commissioner is also using old, decapitated parking-meter posts to which people can tie their bikes, to add to the additional 6,000 new racks that have been ordered.

From the street, Brooklyn Grange, Queens

The view from Brooklyn Grange towards Manhattan

There is an alternative, however, which does not involve having to remember where you put your bike – or worry about it being stolen. In September 2011 Mayor Bloomberg announced the launch of the Alta Bike Scheme that will make 10,000 bikes available around the city. This scheme has a long history, starting with the White Bike initiative in Amsterdam in 1965. Today there are similar projects in 165 cities including Paris – the Vélib – since 2007 and the ‘Boris Bikes’ that were launched in London in 2010. The largest scheme in the world can be found in Hangzhou, China, where there are 61,000 bikes available. The New York ‘Citibike’ is heavily sponsored by Citibank and Mastercard but there have already been some complaints about the pricing structure.

The iconic skyline was less than a mile away but once again it felt strangely distant. I was standing on the roof of a six-storey building in Queens, a borough across the water from Manhattan, less than five minutes on the M subway. To one side I looked out across a busy train depot, to the other ran asphalt and low-level industrial buildings. Around the edge of the rooftop were planted a row of tall looping sunflowers that peered over the side of the building, the only indication of what was hidden here. For Brooklyn Grange is a 1-acre farm in the heart of the city, accessed by lift from the reception area of an ordinary office block.

The project began in 2010, when head farmer Ben Flanner, who had already experimented with roof farms at Eagle Street, Brooklyn, heard that an office block in Queens was considering the development of a green roof in order to improve their environmental standards. Co-opting a group of local restaurateurs and activists, the architects Bromley Caldari and the investment fund Acumen Capital Partners, Flanner persuaded the building owners that rather than a green roof, the top floor could be turned into a commercial farm. And so, over three weeks in spring 2010, 1.2 million lbs of soil was lifted on to the roof and sowing for the summer harvest began.

As I wandered through the rows of tomatoes, beets, carrots, herbs, chard and beans, I spotted a line of beehives, and later I found a small chicken coop. The tender plants had been planted close to the air-conditioning ducts so that they were preserved through winter. In the first full year, the farm produced 15,000 lbs of fruit and vegetables that were sold directly to local restaurants and farmers’ markets. Demand for the produce has been so popular that the farm does not even need to deliver to Manhattan, just across the water. In a recent survey conducted both at roof level and on the street below, it was discovered that whilst on the ground the air quality was as expected from the inner city, six storeys up it was nearly pure.

According to the farm manager, Michael Meier, who had come to New York to work in advertising but, inspired by childhood memories of working on his grandparents’ farm, changed careers and now spends most days at Brooklyn Grange, the project is a privately owned enterprise but with a strong community basis. Thus many of the rows have been sown by local children and there is a large table set between tomato trellises where classes can be conducted. Brooklyn Grange has been so successful that work is already in hand on another rooftop farm in Brooklyn Navy Yard.

There is something wonderful about walking through rows of vegetables and still feeling in the heart of the city. Yet it also felt so obvious; I wondered why we had not all been doing this for decades. In fact it is only recently, following successes like Brooklyn Grange, that city-zoning regulations have allowed similar projects – which encourage green development – to be launched. The new laws, called Zone Green, allow greenhouses to be erected on roofs, along with solar panels and wind turbines; they also promote gardens and local food production, and in general address the wider needs of retrofitting the city, of making greener the city we have in hand. The Mayor’s Office hopes that just by withdrawing current restrictions there could be $800 million of annual energy savings.

However, whilst Zone Green is enabling change to occur in New York, it is still the case that nearly 75 per cent of the city’s carbon emissions come from construction and from heating homes and offices. Everywhere you look, cranes rise into the air, and developers are breaking down old houses, setting new foundations on brownfield sites. The city is constantly in transformation; it never stops being constructed. In an average city 2–3 per cent of the materials are improved every year, it would take at least fifty years for a city to be completely updated; can we wait this long?

Can the rules that allow for the greening of roofs be used to promote more efficient building practice, both in terms of construction and maintenance? We certainly have the technology to improve the buildings in which we work and live. The very same innovation that is creating the smart city (see Chapter 8) can also be used to monitor and regulate energy usage and find efficiencies. As a result, the smart building can control lighting and heating and it uses the latest materials to reduce energy leakage. Once again, the big software firms like IBM and Siemens are investing heavily in promoting the concept of ‘smart building’ as a component of the smart city.

In the US the LEED national standards for sustainable building were created, in the main, for developers constructing new homes or for the rich who can afford expensive turbines and solar panels to improve the value of their homes on the real-estate market. When the project was launched it set the agenda for new thinking about building, making ‘green’ a selling point in housing for the first time, something that added value to the bottom line; and as a result many people saw mileage in speculating on green architecture and design.

But the LEED standards do not deliver on the promise of nurturing the green city. The real proving ground for the green city is not found in how new buildings are constructed but how the older stock and fabric can be converted in order to make it more sustainable. Currently just over 45 per cent of the surface space of New York is taken up with buildings. In 2000 tax incentives were announced to encourage businesses and landlords to retrofit their own properties. Since 2010 government buildings and employees themselves have been leading by example with the addition of solar panels and green roofs. As a result, carbon emissions dropped by 4.9 per cent, nearly 170,000 tonnes in total, between 2009 and 2010.

Following on from the 2007 PlaNYC, in May 2012 the Mayor’s Office launched the ‘Greener, Greater Buildings’ programme setting out a six-point plan to retrofit the city’s existing buildings. As Scott Burnham’s work in Amsterdam on building trust demonstrated, the process of building green is as important as the materials and construction itself. The first of the six points therefore recognises the unique position of cities, by proposing a local New York City Energy Code separate from the local state code. This would let the city – with its very different needs and challenges – set its own agenda and standards.

Secondly, as the report notes, ‘you can’t manage what you don’t measure’,13 so large offices and blocks should be tested annually. However, this procedure should be as simple as possible: the filing of an online form based on recent energy bills. It is estimated that lighting constitutes a large part of all of the city’s energy, so using a system of sub-meters that can find out if offices keep their lights on at night or at unnecessary times of the day will provide the kind of data that could help a company look at its energy wastage. (Thus changing lightbulbs might not change the city, but it certainly has a part to play!)

The plan also outlines a system of energy audits every ten years to check that buildings are emitting as little carbon as possible. And finally, it emphasises the need for a concerted effort to develop the green building economy, encouraging new jobs as well as ensuring advantageous financing for green projects. The programme estimates that these innovations could create 15,800 new construction-related jobs in the city.

The ‘Greener, Greater New York’ plan underscores the idea that there is a connection between the creation of a green city and the development of a green society. New standards of construction and the encouraging of people to work and live in new ways have clear environmental, economic and social benefits. This rather undermines the views held by many exasperated campaigners such as Green Alliance activist Julie Hill, who writes ‘we actually need . . . to have some choices taken away from us’.14 Instead, what is happening in New York shows that we need to see the advantages of making these changes and feel part of the transformation that they bring so that we choose the alternative for ourselves out of preference.

I found something like this in an unexpected place. After visiting Staten Island, I returned to Manhattan and headed to the East Village, a once run-down neighbourhood that had gained a reputation for its edgy, artistic atmosphere. It was here that, in the 1940s, Robert Moses knocked down much of the slum housing and replaced it with the projects, vast social-housing tenements that became synonymous with crime and drugs in the 1980s. Amongst the older streets that circled Tompkin Park, lined with barely gentrified brownstone houses, I was fortunate enough to be following a guided tour prepared for me by the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space, a newly created campaign group hoping to celebrate the squats and local-community gardens of Alphabet City. The tour started at the C squat at 155 Avenue C between 9th and 10th Streets, one of the most famous reclaimed sites in the neighbourhood, which also houses a small theatre known for staging popular concerts.

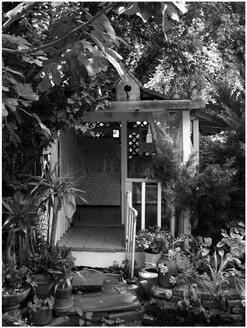

Opposite the squat was a community garden, and upon entering I found an urban paradise. On such a hot day this was one of the most beautiful places I had visited in any city in the world. Trees offered dappled shade in the small plot made out of a gap in the street front where a row of houses must have once stood. The garden itself was divided up into small rooms, each offering different delights: in one, a woman was tending her vegetables with her grandson; in another two men were sitting on a bench, shooting the breeze in the shade; there was a hut with a table, stove and kettle, obviously where the gardeners came together after a day’s toil. I wandered along pathways made of broken-up bricks and found a quiet corner, to get out of the heat and to enjoy this moment of tranquillity in one of the busiest places in the world.

Heaven on earth, a communal garden on Avenue C

There are about 640 communal gardens in New York and at least sixty of them can be found in the dense neighbourhood of the East Village. Many of the gardens emerged from community activism, driven by local campaigners who saw the value of transforming abandoned and derelict properties into verdant oases. Often the plots were taken, like the squats, because no one else wanted them and the legal status was only worked out afterwards. In 2002 the district attorney Elliot Spitzer negotiated that the city should acknowledge the gardens and offer some safety of collective ownership. They are now mostly run by the GreenThumb programme, first started in the 1970s as a partnership between activists and the civic authorities, which helps with developing standards and promoting education. Today over 80 per cent of all community gardens grow food, and over 40 per cent have a link with a local school.

On my tour I visited the Green Oasis on East 8th Street – first built in 1981, when a series of raised beds were planted on top of the building’s foundations that had collapsed from neglect. There, three vividly painted beehives stood within a glade of trees. On the next street, East 7th Street, I found the Ecology Centre Garden, started in 1990, even before the city sanitation department began to recycle. There I found bins for all kinds of waste, while the covered walkways had been made with recycled ketchup bottles and cans. Each park was lovingly tended by the locals, who quietly tilled their patches, or otherwise sat around, chatting and welcoming me in to share their pride. It struck me that the gardens were not just built by the community, but formed one as well.

There was a very different feeling between taking a deep breath standing in the centre of Stockholm and inhaling the air in the heart of New York. Both cities are surrounded by water, but as I gazed out across the sea in front of the Royal Palace on Stadsholmen Island the air was so clean, and the atmosphere so relaxed, it was hard to believe that I was in a thriving capital city. The waves rocked the boats in the harbour to my left, which sat in front of the National Museum, nestling in parkland. To my right was the world-beating contemporary art museum, the Moderna Museet, its white stone glistening, perched on top of the Skeppsholmen Island, which once housed the military academy and naval yards. Had I taken a ferry to one of the nearby islands, I could have swum off the rocks in clear water.

Stockholm is blessed by geography, nestled within an archipelago of islands, so that the city has developed over the centuries as a major port, first as a depot for the Hanseatic League in the thirteenth century, and later becoming a cultural and political capital. In 2009 it was estimated that it was home to 2 million citizens and covered an area of 6,519 square kilometres. In the 1960s the sea around it was so polluted that fishing and swimming in the city’s waters was banned, yet today there are twenty-four official swimming beaches and salmon are often fished and sold. There are nearly 1,000 parks and green spaces, covering over 30 per cent of the city’s landscape, ensuring that 95 per cent of the population are only 300 yards away from the nearest patch of grass.

It is not possible – or always desirable – to pull down all the old stock of buildings and re-route the infrastructure. Yet the disused factories and industrial buildings of the historic centre no longer make sense in the post-industrial city, and it is clear that old buildings are the least sustainable: they leak heat and energy from their joints and windows. Similarly the streets and highways (which lead commuters out to the suburbs) have been designed with gas-guzzling cars in mind. So how do we take the old idea of the city and transform it for the new age? How do we bring people together through this transformation, so that it occurs with them, rather than to them? Stockholm presents the perfect balance between preserving the heritage of the city while also showing a determination to prepare for the future.

In 2010 Stockholm was named the European Green Capital of the Year. This was partly in recognition of the efforts already made by the city, but also because of its future programme, Vision 2030, which identified six main areas for new policy: changing transport policy to make it more environmentally efficient with an emphasis on reducing carbon emissions; encouraging green cars and public transit, and providing bike lanes; reducing the use of toxic chemicals in manufacturing and construction; more efficient use of energy, water and land; improving waste management; and finally ‘a healthy indoor environment’: upgrading social housing and reducing noise pollution.

While the average European carbon footprint stands at 10 tonnes per capita, as opposed to 22 tonnes per capita in the US, Stockholm has already reduced its carbon emissions to 3.4 tonnes per capita and it promises to be fossil-fuel free by 2050. This reduction has been brought about by improving the city’s infrastructure and promoting public transport, as well as developing a widespread bike culture, with an ‘ecobike’ system and the establishment of an extensive cycle infrastructure, so that on any winter’s day 19 per cent of Stockholmers will be using their bicycles – a figure that rises to 33 per cent in summer.

Stockholm has also been able to improve energy efficiency in heating. The city government, alongside the energy company Fortum, has invested heavily in alternative sources of energy, including biofuels, solar power and hydropower (fossil fuels are only used when the weather is really cold); in addition 80 per cent of the city is now supplied by a ‘district heating system’, so that power stations generate heat as well as power that is then distributed around the city through insulated pipes. Such a scheme takes a long time and huge initial investment but it has major long-term benefits: since 1990 emissions of greenhouse gases in the city have dropped by 593,000 tonnes.

Clear water, bicycles and clean air: the benefits of a green Stockholm

Alongside green initiatives and the development of infrastructure there is also a strong commitment to education. Stockholm believes in its role as a creative capital and knows that as it grows it will also become more innovative; thus the future of the city begins at school. Together with the development of transport hubs, cleaner, more open neighbourhoods and new shopping areas, there is also a pledge to invest in the Kista Science City, the Stockholm Public Library and the College of Arts, Crafts and Design at Telephonplan by retrofitting and repurposing the existing industrial buildings rather than planning the latest innovations in new suburbs far from the city centre. Thus Stockholm is determined to become greener but not at a cost to the city’s economic competitiveness in the global market.

And how does this change the city? Do the citizens feel healthier and cleaner as a result of the greening of Stockholm? Talking to Swedish friends who live there, I discovered that many of the changes have happened without controversy or complaint. Rather, they have grown out of the long-standing personality of the city itself, for Stockholm has always placed a premium on community. Thus, why should citizens not share heating arrangements when sharing is not seen as a disadvantage? Projects on this level take huge governmental will and resources, but they mean very little unless the rest of the population are as engaged as their leaders in the future of their shared city.

As cities like Stockholm – in contrast with, say, New York – show, the more equal and trustful a city is, the more likely it is also to be green. It is impossible to project a sustainability programme without engaging with the people on the street, and this is almost impossible when the level of trust is low. Why would you recycle if you did not trust your neighbour? How can the city be green if there is one rule for the rich and one for the poor? This can be seen in the decisions that people make when they get into their cars. An efficient public-transport system reduces not only congestion and pollution but also health inequality, but some of the barriers for using such transit include the fear that it is inefficient, and the social stigma of ‘riding the bus’. Getting cars off the street and cutting out unnecessary journeys has a social as well as environmental result: it reduces carbon footprint and improves air quality, but it also, as we saw with Appleyard’s experiments on his Heavy and Light Streets, enhances communities.

I was reminded of this fact when I went to meet Colin Beavan, a writer living in Manhattan who decided to reduce his carbon emissions to zero. He recounted the travails and the joys of his year of living green in a wonderfully entertaining and honest book and documentary film of the same name, No Impact Man. The story is a salutary narrative that is not afraid to expose the difficulties and sacrifices necessary to get used to a more sustainable life. In the end, the freedoms and benefits were palpable.

On many occasions the results were unexpected and amusing. Early on, Beavan realised that he could no longer order takeaways because of their cardboard containers, and his misery was compounded when he could not even indulge the impulse for a slice of pizza on the street because of the plastic plate and packaging. Getting around the city became hard and Beavan was transformed into a bicycle fanatic; however on at least one occasion he could not take his daughter to a birthday party because it was raining. Discussing holiday plans with distant parents also became an ethical as well as emotional minefield.

As he began to shed all unnecessary things in life he recorded how his day-to-day existence was changing. Thus one day he calculated that because he could no longer use lifts, after taking the dog for a walk three times a day, dropping off his daughter at childcare and completing his daily chores, he had walked up 124 flights of stairs – nine more than the Empire State Building.

Yet over the months, as they turned off the heating in winter and used only candles, recycled as much as they could, composted on the fire escape, and grew their own vegetables in a communal plot, the Beavan family began to transform. In the end, Beavan admitted that the fear of change was more dangerous than the change itself. When they turned off the electricity, having invited a group of friends around to the apartment for the ceremony, each holding a candle in preparation, the moment before the circuit breaker was pulled was much worse than the first second of darkness. ‘What’s hardest? Everybody wants to know. Is it no packaging or the biking everywhere or the scootering or the living without a fridge or what? Actually it’s none of these things. What’s hardest is habit change. Plain old forcing yourself out of a rut and learning to live differently. Everything about yourself wants to fall back into the rut, at least for a while. By “for a while”, by the way, I mean a month. That’s how long they say it takes to change a habit.’15

Beavan’s experience shows that creating the sustainable city begins with the family and then grows outwards. Yet this does not mean that the city should just turn off the switch and descend into night. Rather, their experiment allowed Beavan and his wife to understand what was necessary and what was not: ‘there were two parts of the equation: one is figuring out what is the good life – how many and what kind of resources we need to make us happy. The other is figuring out how to deliver the same level of (reduced) resources, by western standards, to everyone in a sustainable way.’16

This sounds so simple, but how do we go about making it work at a global level without us all having to go through a season without electricity to jolt ourselves into action? There are, thankfully, a number of surprisingly small and common-sense changes we can make to our everyday lives that can make a difference. For example, the UN Environmental Programme offers a number of simple solutions to the question of ‘thermal comfort’, such as putting on a jumper instead of the heating over the winter and rolling the blinds down rather than turning on the air conditioning in the summer. The programme also highlights the fact that many shops feel obliged to keep their doors open, thus letting out a great deal of energy – sometimes 50 per cent of all heating costs (indeed some use a machine that blows a jet of hot air across the doorway to stop leakage); but why do they not simply close the door?

Since his experiment, Beavan has been attacked by some commentators. The leading environmental correspondent for the New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert, dismissed his efforts as an ‘eco-stunt’. She argued that, because Beavan was not in control of the heating system in his building, and because he was able to use the electricity from the Writer’s House in which he wrote his blog, this proves that it is actually impossible to live inside the city without having some kind of impact.

These are fruitless objections that miss the point. The whole city cannot follow Beavan in his experiment but it is interesting to see how far one can go if one tries, and perhaps it will encourage others to cut back. Beavan reminds us of our individual responsibility as citizens – the people who live in cities – to look for ways that we can change our own behaviour to deliver a greener metropolis.

Beavan’s darkened flat in Greenwich Village stands in stark contrast to the massive works currently underway at Fresh Kills, but they are both necessary in order to prepare the city for the coming environmental challenges.