5

Everyone had been given directions in advance, as well as the number passcode for the security gate. It was a short walk from the Métro down rue Acacia and then a few yards to the large, green iron doors that blocked off the entrance to the mews behind. Already one could hear the murmur of activity on the other side as I punched the number into the touchpad and waited for the click of the releasing lock. With a push the gate opened, and as I stepped through I felt as if I was passing from the city into a new, unfamiliar place.

Every Sunday evening for the last thirty years, 38 rue de la Tombe Issoire, Paris, has been a city within a city; for here Jim Haynes has held an endless supper party, the door open to anyone who wants to enter, the table ready for all who wish to eat, the conversation a babble of different languages, accents, generations and sensibilities – by reputation this is a place where once everything, and anything, was permitted. But it was Thanksgiving 2011 and, after hanging up my coat and with a plastic glass of red wine thrust into my hand, I made my way into the main room where forty or so people were already bumping into each other, introducing themselves, finding connections and listening to each other’s stories.

I introduced myself to Jim, who was sitting on a stool near the kitchen area where an oversized turkey was standing ready for carving. Jim is a remarkable lightning rod for the last forty years. Born in Louisiana in 1933, he enlisted in the US Air Force after university, and was sent as a Cold Warrior to a small listening base close to Edinburgh, Scotland. He soon became more interested in the life of the city than preparing for World War Three, and was given permission by his superiors to live in the centre and study at the university. Later he travelled around Europe and returned with plans to set up a bookshop that quickly became a hub for radicals, writers and publishers. He then became involved with the emerging Edinburgh Fringe Festival, setting up the Traverse Theatre, organising it as a club to circumvent the censoring Lord Chamberlain’s office.

Moving down to London in 1967, he founded the Arts Laboratory, the avant-garde epicentre of the swinging capital, publishing the International Times and hosting the UFO events at the Roundhouse with its house bands Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine. A trailblazer for the Free Love movement, he produced the magazine SUCK from Amsterdam and curated the first Wet Dream Film Festival there. At the same time he moved to Paris and began to teach at the university, during which period he moved to rue de la Tombe Issoire. At first, he and a friend Lenny Jensen rigged up a local cable TV station, linking together all the neighbours along the mews, sharing films and videos. He renamed his atelier the Embassy of the World and started to issue world citizenship passports to replace national documents, until he was taken to court by the French authorities. He also began to hold dinner parties and picnics for the community. Over time, these Sunday evening salons gained a reputation and became an institution; today, they are a barely kept secret that people have spread across the world.

Jim Haynes at home, 2009

On the evening I was there, I was immediately approached by an American woman in her fifties. Many people had turned up alone and this sense of fellowship set out the rules of the room – you were free to talk to anyone you wanted, to introduce yourself and ask questions: How did you hear about Jim? What are you doing in Paris? Groups of people huddled together and then moved on, interconnecting and creating a network that quickly weaved through the whole room, and then outside into the night air where other groups bunched together, smoking. This was a city in the making – strangers meeting strangers, developing the rules of engagement as the evening progressed; finding the language and practice of community as we went along.

The American woman had moved to Paris six months ago, and heard about Jim’s parties through a friend. I then spoke to a young French banker who had previously worked in London but had returned home and was looking for work. He was with his girlfriend, and was talking to Colin, another American from California, a music scholar who was setting up a chamber orchestra in Paris. He introduced me to a Swedish couple, who were in the city, like me, for the weekend. There was also Pat, who wrote the subtitles for French films and was trying to get a novel published; Suzi, a South African architecture student who had spent the day in Montparnasse Cemetery; two sisters, Stef and Pam, who had been coming to Jim’s for over fifteen years and conducted tours for rich Americans around the ateliers of the leading haute couture designers and fabric shops.

Throughout it all, Jim himself sat on his stool and surveyed the scene he had created. When I asked him why he still did this, despite one heart attack and another health scare, he admitted that he was still interested in people, still wanted to share with strangers and make friends, that this making of a community, for however brief amount of time, was a reason for living.

At rue de la Tombe Issoire, a community comes together, shares food, drink and conversation and departs in the course of an evening. The ecology is simple to define and the rules of engagement are quickly acquired despite any initial shyness. Above the seeming chaos of the kitchen quarters, this evening is a momentary community, self-organised and complex, but a community in every sense of the word.

The idea of people coming together, sharing the same space and getting on with each other sounds simple, but 7,000 years of urban history often disproves this. It was once far easier to know who you were and where you came from; the definition and requirements of citizenship were set out clearly. Yet, as the city grew beyond the boundaries of the first walls, the question of belonging became more problematic. How can you prove you are who you say you are? What are the codes of practice, the behaviour of ‘cityness’, and how do they evolve? How can you define community when people are on the move so much?

As the population of the world becomes increasingly urban, redefining community is an ever urgent question. People, families and groups are coming to the city now in greater numbers than ever before; they are arriving at places that are so large and diverse that they cannot simply be defined by one identity. Community may be many things: a shared space, a way of behaving, as well as people; yet the process of belonging is more than any one of these things alone. It is an ecology that combines place, people and the way they interact.

But it seems that living together creates serious problems, that jamming so many people into such a tight space makes the city a ticking time bomb ready to explode. Somewhere between the experience of an evening in a Paris salon and the full scale of 9,000 years of urban history, the problem of community had become an intractable crisis. How can we challenge this scenario?

We are hardwired to be together. Despite the fact that we have been told most of our lives that we are all individuals and that survival of the fittest was the only rule of the game, we have been genetically designed to seek each other out and form communities. We are social animals and, as a result, the city is the most natural place for us to be. Our personalities are formed by our relationships with others; our language is shared; it is the connection with others that makes us happy, smarter and more creative. It is only our ability to cooperate that has allowed us to survive thus far. Collaboration is the engine of complexity, connecting us with each other, strengthening the social bonds. As evolutionary biologist Martin Novak writes: ‘Cooperation is the master architect of evolution.’1

The way and the extent that we work and live together is often surprising. Take, for example, a crowd. In 2011 a team at the Zurich Federal Institute of Technology wanted to see whether they could scientifically work out the collective behaviour of a large group of people walking down the street. They asked whether people followed certain rules or whether a busy sidewalk was a picture of chaos as people bumped into each other like random billard balls cascading across a table. Using tracking devices, Medhi Moussaid’s discoveries were unexpected: in each scenario the crowd quickly adopted the characteristics of a complex system and began to self-organise. Almost from the outset two lanes started to form to allow for bodies to flow in opposite directions; where a bottleneck was encountered an unwritten rule of how to step to one side was adopted.

One particular result, however, revealed that although this movement was purely based on probability – guessing in which direction the other was going to go – where you come from had an influence on which side you chose. In most countries in the west, we will instinctively move to the right; in Asia, to the left. Most of the time this causes manageable problems but at moments like the Olympics, or at the Hajj, when visitors from around the world congregate in one space, it can cause chaos.2

The added dilemma to this scrum is that many people within the crowd are not acting alone: 70 per cent of any crowd is part of a smaller group. When three or more people are walking together they often adopt a formation depending on their speed. If they are walking fast they usually adopt a penetrating shape, with one leader cutting ahead of the two wings. If the pace is a little more relaxed, the group often forms a U or V with the central figure hanging back.

In addition, just as Oscar Wilde declared that everyone in London looked like they were late for a train, it is the case that people from different nationalities walk at different speeds. In a groundbreaking experiment, Robert Levine of California State University in Fresno timed the average walking speeds in thirty-one different cities and found that nine out of the top ten – Dublin, Amsterdam, Bern/Zurich, London, Frankfurt, New York, Tokyo, Paris, Nairobi, Rome – were wealthy cities and economic factors such as earning power, cost of living and time accuracy were key factors.3 When time is money, we tend to pick up the pace.

We have a biological need to be together but the exact measurement of what that togetherness means is up for grabs. There are rules that govern how we come together, but they are different dependent on where you are. The problems of community are often what is lost in translation.

One thing that connects the crowd with a more permanent community is the problem of proximity. For Jean-Paul Sartre, hell was other people, but the chain-smoking existentialist was wrong. Returning to Jane Jacobs’s neighbourhood on Hudson Street, the transformation of a random gathering of people into a community is formed through a combination of the routines and relationships that accumulate over time, mixed together with the more immediate connections made in the moment. A community is not a family with its strong ties and obligations but an evolving, turbulent network of weak links, familiar faces and rehearsed rituals.

Density, the necessities of shared space, has a big part to play in this process. In Jacobs’s Greenwich Village a good city street neighbourhood achieves a marvel of balance between its people’s determination to have essential privacy and their simultaneous wishes for differing degrees of contact, enjoyment or help from the people around. This balance is largely made up of small sensitively managed details, practised and accepted so casually that they are normally taken for granted.4

Density defines a city, and therefore the community. It is the key problem when there is overcrowding, the network through which diseases can decimate a neighbourhood; when things get too crammed, density turns old parts of the city into slums, where poverty huddles and becomes stuck. It is the overfull bus that forces you to wait for the next one. It is the social-housing waiting list that leaves some children in poverty only a few hundred yards from the richest enclaves of London. It is the equation behind the queue for the water tap in the Mumbai slums, and the ten-hour traffic jam in Lagos. With the prospect of increased urbanisation in the next thirty years, particularly in parts of the world where there are already problems of managing the infrastructure, density could easily be the biggest challenge of our age.

However, we should also look at the advantages of living close together, and make sure that as we attack the problems of overcrowding we do not do away with the benefits of living cheek by jowl. We now know that large, dense cities are more creative, that the network of weak ties, diversity of parts and the added competitiveness encourage innovation. But urban density also has an impact on fertility rates, reducing the number of children within a family. It can reduce the amount of energy that one uses, and improves the efficiency and productivity of everyday life. Perhaps most surprisingly, and despite many misconceptions, being close together also makes people behave better. Although there is a long-held assumption that the faceless crowd is an aggressive mob, density actually encourages civility.

In a 2011 report by the Young Foundation, three communities were tested for levels of politeness: Newham, one of the poorest and most diverse boroughs in east London; Cambourne, a county town in Cambridgeshire with a growing young population; and Wiltshire, one of the least densely populated counties in the south-west of England, 90 per cent of which is classified as rural. Over a series of tests and observations, the study looked at levels of basic civility and politeness, from saying ‘good morning’, to issues of honesty, respect and trust.

The results were unexpected; where it is often assumed that incivility is linked to disadvantage, diversity and poverty, the opposite was found to be true: ‘We found very high levels of civility in some disadvantaged, diverse places, as well as instances of serious incivility, in the form of intolerance and rudeness, in more prosperous and homogeneous contexts.’5 As an example of how people who lived close together were forced to be kind and observant of each other, the researchers highlighted Queen’s Market in Newham:

We observed how shoppers of a range of ethnicities queued patiently and stepped out of the way of prams and elderly shoppers. Shopkeepers were adamant that maintaining civility was critical to their commercial success. Those who treated customers from different cultures or ethnicities rudely soon went out of business. Stallholders had adapted with the times – in east London it is not uncommon for Cockney salesmen to speak fluent Urdu, for example.’6

The city forces people to adapt their behaviour, to be more open and civil; the diversity of the community does not have to nurture divisions but accommodation and politeness. However, there is no golden mean of density that produces a well-balanced community. For example, even as we look disparagingly at London or Paris for being too cramped it is worthwhile remembering that the most densely packed society in Europe is not one of the giant industrial northern cities but Malta, a place that many people from the larger cities escape to for peace and quiet. The pursuit of urban density, therefore, is only one of the means to develop the ecology of community. It can deliver benefits, moderate and modify how a community develops, it can encourage diversity and innovation, enrich the communal life through weak links and associations but it is not the gift of happiness itself.

Detroit is a stark example of how changing levels of density can impact on a community. In 1932, amidst the aftershocks of the Wall Street Crash, the Mexican artist Diego Rivera was invited by the Detroit Institute of Art to draw a series of vast murals to celebrate the city that was at that time suffering heavily from the Great Depression. Before the crash, Detroit had been the home of the American automobile industry; situated by the Great Lakes and linked by the new railway, the city established itself as an industrial centre in the late nineteenth century; in the 1900s Henry Ford took advantage of the thriving carriage trade and set up his first workshop there in 1899. Soon he was joined by General Motors, Chrysler and American Motors. By 1912 the Highland Park plant, the largest industrial complex in the world, was producing over 170,000 Model Ts a year.

In response Detroit’s population exploded, rising from 466,000 in 1910 to 1,720,000 in 1930. Yet that year demand for new automobiles plummeted, and there were massive lay-offs from the factories; half the workforce were dropped, pushing over two-thirds of the city under the poverty line. Into such a febrile atmosphere, it was perhaps dangerous to commission the renowned Marxist artist to devise such a massive work of art – charting the history and development of the city’s industry from its agricultural roots to the modern assembly line. Rivera worked on the mural for the next eleven months. In a series of twenty-seven panels he devised a temple to industry, with the car as the highest form of man’s achievement. It presents Detroit’s history as manifest destiny, facing the problems of the Great Depression and conquering all obstacles; but the city would soon be seen to be fragile indeed.

By 1950 Detroit had a peak population of 1.8 million, attracting a new army of workers from the south and becoming the second-largest metropolitan area in the US. The arrival of these – mainly black – migrant workers had its own catalytic impact as the richer white residents got into their cars and moved to the suburbs – white flight, as it was called – making the city rich but dangerously divided. The industrial success of the American empire was built in the factories of the city, but the spoils were unevenly shared. The wealthy white families dominated the centre of Detroit as well as the exurbs, the neighbourhoods outside the city boundaries, linked by expressways that bounded over the suburbs, where many black familes found themselves increasingly stuck. Following brutal riots in 1967, which killed forty-three and destroyed 1,400 buildings, there were attempts to break down the racial barriers with a new plan for Midtown that aimed to integrate the disparate communities. However, as the city started to decline, the first signs of deprivation were seen in the black suburbs. Jobs were lost, mortgages became unserviceable and foreclosure soon followed; in time demand for housing flatlined.

The fall of Detroit

Today, Detroit is in trouble: the orders for American automobiles have slowed while international competition has undermined US supremacy; the city has turned into an industrial ghost town. This has had a devastating impact on the population, which was reduced by 25 per cent between 2000 and 2010. The average income there is half of the national median. In 2009 the unemployment rate stood at 25 per cent and the murder rate ten times worse than New York. The average house is worth little more than $10,000 and over 50 per cent of all children live in poverty.

As a city built on cars, Detroit was also a city dominated by freeways leading to suburbs that now are almost empty. In a 2009 survey it was found that many neighbourhoods were almost abandoned, 91,000 lots in total were standing open, 55,000 of these had been foreclosed. Therefore the city was in the impossible situation of being forced to spend $360 million a year to provide services to houses which were empty and were not generating tax revenue. What was the mayor, businessman and former All-Star professional basketball player Dave Bing, to do? Desperate circumstances called for dramatic measures.

To start, people looked at ways to revive downtown, hoping that if the centre of the city could revive then the rest would follow. One early response was to develop the Detroit People Mover (DPM), a monorail that runs in a circuit around the downtown region aiming to deliver swift transit around the city. There was also a concerted effort to develop the Detroit International Waterfront, a collection of plazas, riverside walks, hotels, music halls, theatres and cultural centres. The Renaissance Center is a cluster of interconnected skyscrapers including the headquarters of General Motors, and numerous banks.

But surely the problem was not just about reviving the centre? Reducing the city to its central business district does not offer homes, schools and security. In addition, Detroit is cursed by a wealthy outer belt of exurbs, connected to the centre by fast-flowing freeways. The problem is the wasteland, the inner suburbs, caught between the centre and these exurbs. Once these neighbourhoods were the forcing ground of the city, home to its workforce and community, but now stand as empty land. In response many planners proposed that Detroit use the bulldozer and shrink the city back into a liveable density. Using the 2009 neighbourhood survey, it was decided that Mayor Bing needed to select the winners and losers, the communities that would be leavened to the ground, and those that would receive government funding, with the warning ‘If we don’t do it, you know this whole city is going to go down.’7

Since then, although there has been much discussion about ‘right-sizing’ Detroit, the bulldozers yet have to move in. Unlike Barcelona, where Joan Busquets was encouraging increased density in a traditionally dense community, the people of Detroit do not have a history of living close together. As some critics point out, even a depopulated Detroit is more dense than many of the sun-belt cities like Phoenix or Houston, therefore the issue might not be density alone. Others, like economist Ed Glaeser, say the problem is not just about bringing people together but also providing them with something to do, as well as the education and social tools that might encourage them to want to be there.

Still others have complained about how one could effectively conduct this ‘right-sizing’ which would force people to leave their houses, and close services and neighbourhoods. As a result even Mayor Bing admits that the Detroit Works Project has taken longer to start than hoped. After taking the opinion of over 10,000 stakeholders into account through endless neighbourhood meetings, there has also been a concerted rebranding exercise to get locals on board, convincing people that this was a shared vision for the city rather than one imposed from city hall. In the meantime, the public-transit system has been privatised, and therefore taken off the government’s books. The new owner, 25-year-old Andy Didorosi, promises to run the scheme at cost, but has reduced the service to one bus riding a loop through the main neighbourhoods.

There are some positive signs of regrowth even as discussion of right-sizing continues. Although not the solution in itself, downtown Detroit is becoming attractive once more to businesses. In summer 2011 Quicken Loans moved into the Chase Tower from the suburbs, bringing 4,000 employees into downtown. Owner Dan Gilbert has gambled heavily on the rebirth of the city centre, buying real estate, investing in retail, as well as encouraging other businesses into the area. One of the markets that could see real growth is technology start-ups and Gilbert has also set up Detroit Venture Partners to take advantage of the new culture. This is reinforced by Tech Town, established by Wayne State University Research and Technology Park, General Motors and Henry Ford Health System as an incubator for innovation. In 2010 Detroit was the largest market for hi-technology engineers – even more than Silicon Valley – as the car industry tried to find a route out of its depression.

Detroit is a painful reminder of the relationship between the fabric of the city and the development of a community. This is not simple or straightforward, however: one can find strong communities in slums and terrible loneliness in the richest enclaves. Yet the interaction between ourselves and the places around us is so complex that it has fascinated architects, psychiatrists and politicians. On a panel at the LSE in 2010 the architect Will Alsop described a visit to Lyons, France, where a new art gallery and historical district – in pursuit of the Bilbao effect – had transformed the city centre. Sitting in the town square, he continued, he noted there were many young kissing couples, canoodling away oblivious to the other passers-by. Was this the effect of architecture? he asked; can we create a place that encourages people to kiss?

Psychological experiments often reveal unexpected connections between ourselves and the environment. In one example of psychological priming, a group of people were asked to walk along two equal walkways: along one walkway were displayed pictures of old and infirm people; on the other were images of younger, more vital models. In every study, people moved faster along the second walkway. Priming is the study of how external stimuli can influence behaviour or responses, but how far can this go? A place can have an emotional impact on people – a church has a sense of the sacred, a palace resonates pomp and power – is the same also true of the public spaces of a city?

With tongue firmly in cheek, the homepage for the Cardiff University Sociology Department describes Georg Simmel as ‘rather like Gary Barlow out of Take That, the one that had all the good ideas and did all the work but none of the fans fancied or could remember what he looked like’.8 Born the son of a wealthy chocolatier in 1850s Berlin, Simmel was rich enough not to work and so took the role of a private lecturer at the university, where he became popular amongst students and befriended other thinkers such as Max Weber, Rainer Maria Rilke and Edmund Husserl. The forgotten father of sociology, he is now remembered for his philosophy of money; however at the time it was his 1903 essay, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’, which highlighted the ills of urbanity, identifying the struggle between the individual’s need to be free and the demands of the ‘socio-technical mechanism’ of the city.

Simmel’s work soon made its way across the Atlantic and in the 1920s was adopted as a bible by the Chicago School of Sociology. The group, which included Nels Anderson, Robert E. Park and Ernest Burgess, gained fame for their ‘ecological’ approach to studying urban life: that the city was a place of differences, and the environment was a key factor in determining human behaviour. In particular, they were fascinated by the relationship between cities and their anti-social or marginal communities, and how this could endanger or stimulate a community. As Park, who had studied with Simmel in Berlin and later translated his work, wrote: ‘The city magnifies, spreads out and advertises human nature in all its various manifestations. It is this that makes the city interesting, even fascinating. It is this, however, that makes it of all places the one in which to discover the secrets of the human heart, and to study human nature and society.’9

The Chicago School saw the city was a problem, a place that forced people into new behaviours. Park himself was interested in the process of immigrant assimilation into cities, and the resultant racism that met new arrivals. Similarly, Nels Anderson wrote about the hobo, highlighting the problem of homelessness; Ruth Shonle Cavan in 1929 wrote a book about young women coming to Chicago to work and the opportunities and problems that they faced. Meanwhile the black researcher Edward Franklin Frazier contextualised the issues of life within an African-American family in The Negro Family in Chicago. The Chicago School not only gained attention because of the subject matter of their work but also as a result of their method: promoting close and systematic observation rather than philosophical speculation on the formation of human nature or what people want. This scientific study of where cities went wrong went hand in hand with a reformist agenda: exploring not just how the city did not work, but also how it could be fixed.

The current incarnation of environmental psychology began in the 1970s, when the emphasis moved from grand planning schemes to a more refined study of the relationship between the individual and the wider environment. In particular, this new discipline was interested in the role of place identity, how a certain environment feeds into a sense of self; the impact of density upon a sense of well-being; the problems of noise, weather and pollution; how women and men perceive the urban environment; how design improves a sense of place. This movement therefore combines the results of studies in environmental psychology and psychological priming with the latest ideas in architecture. As Harold Proshanksy of the New York Graduate Center noted, the discipline is hardwired with the hope of improving the city and as a result has developed a number of strategies that underpin our ideas of urban renewal.

In general these efforts focus on well-meaning areas such as healthcare, crime reduction and combatting poverty. What does a healthy city look like? Can we build places that make us safer? What are the changes to infrastructure that make a real difference to people’s ability to succeed? It is often the small or unexpected moments that make up our experience. Thus the height of a window, letting in the sun at only certain parts of the day, can have an impact on happiness. Our proximity to green spaces can have an impact on our moods as well as a child’s social development. Street lighting can make one feel safer when walking at night. How can we change a streetscape to make a city more walkable? Take, for example, the problems of shadows in the modern metropolis.

Recall the sense of joy that comes from sitting in a city square with the sun on your face. It is sometimes easy to forget how important sunlight is in our everyday lives. In the nineteenth century social engineers such as Florence Nightingale promoted the idea of fresh air and sunlight as health-giving conditions. For the Victorians, sunlight, clean water and pure air constituted the principal components of the ideal city. This was particularly a cause of debate in New York for, as architect Michael Sorkin observes in the wonderful hymn to his home city, Twenty Minutes in Manhattan: ‘Much of the modern history of New York’s physical form is the result of debates over light and air.’10 By the 1870s there were complaints that the high tenements that had been built to house the rising population were obscuring the sky and filling the air with a putrid stink. As a result a height limit was put on all residential buildings in the 1901 Tenement Housing Act.

But this did not stop architects who were developing the business district and in 1915 work started on the Equitable Building in Lower Manhattan to replace previous offices that had recently burned down in a fire. Out of the ashes the architect Ernest R. Graham designed a neo-classical block that stood sixty-two storeys tall above the city. As it was being built it soon became clear that the vast edifice would cast a shadow across 7 acres, plunging the neighbourhood and the surrounding buildings into permanent darkness. In response the New York government set out the 1916 Standard State Zoning Enabling Act which imposed limits on the maximum height of buildings, where they might be built, as well as devising a code for ‘setback’, designing a building so that as it grows skywards, it also tiers inwards to reduce its shadow, as can be seen in the iconic designs for the Chrysler or the Empire State Buildings.

Shadows and the city: Manhattan, 2012

In the post-war period, architects once again began to question these regulations. The modernist aesthetic, inspired by Le Corbusier, demanded bold, regular blocks of pure glass and metal; rather than being ‘set back’, these new skyscrapers were being built within plazas so that the shadow would not interfere with other buildings. This new approach to the city was encapsulated by the Seagram Building created by Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. Now there was less emphasis on the experience of the city beyond the plaza that hugged the ankles of new skyscrapers, because it was assumed that everyone was in their cars; what sunlight one might encounter could be reflected from the shining glass of the modernist monuments onto the streets below where it would palely glisten along the chrome finish of a polished Cadillac.

Yet, even as Robert Moses was planning his Futurama city, there was opposition. In addition to Jane Jacobs’s successful protests against LoMex, others were starting to discuss the idea of ‘solar access’, the essential right to sunlight as a key quality of life. In particular, Californian architectural thinker Ralph Knowles was developing the notion of planning cities around ‘solar envelopes’ which determined the height and orientation of buildings according to the cyclical solar movements.

It seems unlikely that this would ever be put into practice in Manhattan but in 2010 Mayor Bloomberg picked up on many of the key notions of the right to solar access, and how the persistent presence of shadows would impact on public life in the city, as set out in the excitingly titled CEQR Technical Manual: ‘Sunlight can entice outdoor activities, support vegetation, and enhance architectural features, such as stained-glass windows and carved detail on historic structures. Conversely, shadows can affect the growth cycle and sustainability of natural features and the architectural significance of built features.’11

Environmental psychologists have spent a long time studying the impact of sunlight and shadow, conclusively showing that more natural light affects the well-being of workers or families within the space. In particular, scientists discuss the importance of sunlight for the body’s cicadian rhythm, or nature’s alarm clock. This is the natural process that regulates the daily biological rhythms, regulated by the hormone melatonin, secreted from a gland in the centre of the brain, which can have an impact on conditions such as Seasonal Affective Disorder. This has encouraged many architects to rethink the importance of sunlight within their design.

It is this kind of experiment that informs environmental psychology, the link between place and behaviour. The power of this connection is also the thinking behind the well-known ‘broken windows theory’ that first appeared in a 1982 article by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling in the Atlantic Monthly. In the essay, the authors reported on the relationship between disorder within a community and crime: a chaotic environment in which vandalism is a reflection of a ‘don’t care’ attitude. There, the authors proposed that it is better to repair broken windows in a run-down block than to wait for vandals to trash the whole building: ‘One broken window is a signal that no one cares, so breaking more windows costs nothing . . . “untended” behaviour also leads to the breakdown of community controls.’12

When Kelling went to work for New York City Hall the policy became part of a wider ‘zero-tolerance’ policing strategy. In his own account, William Bratton, the police chief who adopted Kelling’s ideas, reports: ‘Ten per cent of New Yorkers experienced violent crime. But 100 per cent experienced the city’s disorder: fare-beaters and drunks on the subway, mental patients off their meds wandering the streets, prostitution operating in the open. Long lines, high taxes, poor service. Broken neighbourhoods, broken people, broken windows.’

Bratton felt that while the police spent most of their time responding to crimes, they did nothing to prevent it. He started not with windows but the petty crime of fare-dodging. At the time it was calculated that over 17,000 fares at $1.15 were being avoided every day. Using plain-clothed police and a system of ‘mine sweeps’, he got dramatic results: ‘Fare-beaters tend to have character flaws. One in seven are wanted on warrants or probation violations. One in twenty-one carried an illegal weapon . . . Now it was about making felon collars. And when fare-beating went away, crime fell, and so too did the sense of disorder. And when it did, ridership returned . . . Take care of the small stuff, and you head off the big stuff.’13 The sight of a daisy-chain of offenders being pulled through the station became a highly effective deterrent and recovered nearly $70 million in lost revenue a year.

Some critics believe that the repairing of windows happened to coincide with a falling crime rate in New York, so that small interventions were amplified by wider social changes. Others felt that Bratton was heavyhanded. Nonetheless the results were emphatic: crime rates dropped by 0.3 per cent in 1990; 4.4 per cent in 1991 and 7.8 per cent in 1992. By 1996 serious crime had fallen by 32 per cent, the murder rate dropped by 47 per cent and car theft by 40 per cent.14 It is a powerful example of how changing the environment can influence behaviour; and it does not just work with broken windows. Experiments in Holland concerning graffiti suggest that allowing one tag to remain on a wall often leads in time to the complete surface being covered. The Dutch research team discovered that in some cases, a disorderly environment increased the likelihood of criminal behaviour by nearly 50 per cent.15

Being able to manipulate or manage people through design does not come without concerns. Just as one city can plan for better community, others can use the same scientific principles to reinforce political control. In addition, any project that provides planning solutions in the form of strong medicine, without consultation of the people it is going to affect, is also likely to confront unexpected consequences.

Solutions from planners, developers, architects, politicians and urban bloggers are legion; but what if the community wants to reboot itself rather than have transformation imposed upon it from well-meaning decision-makers? Robert Putnam’s classic study of community, Bowling Alone, offers a disheartening view of modern society. With an abundance of observation material and statistics, he makes the watertight argument that our sense of community and our participation in communal activity has collapsed. Using the image of the lonely bowler throwing his ball down the alley, where once he would be part of a team, our sense of who we are and where we fit in has atomised and become dangerously small. As he calculates, more Americans are bowling than ever before but league bowling has plummeted. This is, however, a symbol of a wider malaise: ‘We spend less time in conversation over meals, we exchange visits less often, we engage less often in leisure activities that encourage casual social interaction, we spend more time watching and less time doing. We know our neighbours less well, and we see our friends less often.’16

Putnam goes on to show how the loss in communal participation has unexpected impacts elsewhere within the city, affecting levels of honesty and trust, attitudes to others within the group, establishing the weak ties that make a city complex and creative, and potentially the foundation of democracy itself. He raises this spectre in order to confront it, to warn against the decline and to show that it is not necessarily inevitable. In particular, he promotes the notion of ‘social capital’, the benefits that come from association and being part of the group, the idea ‘that social networks have value’, that they deliver both private and public good.17 He argues that being a good neighbour makes us better people; conviviality is the tradeable commodity that creates a better place around us.

But this is often very difficult in the hectic modern world. We have become accustomed to our solitary ways: travelling in cars cuts us off from others and we find waiting for a bus or strap-hanging on the tube an unpleasant experience. Work is so all-consuming that we have little time for our families let alone helping out in the community; or even doing things we like, such as going to the theatre or listening to music. Most of us now live in suburbs where there are fewer people and sprawl allows us to live behind fences. We no longer go to church in the same way we did before. We are still interested in sports, but now we are more likely to be a spectator than get involved. It is far easier to run on the treadmill when one has time rather than organise life around weekly practice when others rely on you to turn up. Membership of political parties has plummeted just as voting figures have dropped. Putnam calculates that television itself is responsible for at least a 25 per cent drop in social interaction. Modern life is driving us apart, it seems.

Perhaps it is not surprising, therefore, that although cities are shared spaces, yet we have become increasingly obsessed with privacy. At the end of a hard’s days work there is a certain joy in closing the front door and locking the city out. Even as we use the city in the course of an ordinary day we have become suspicious and unsure of the shared spaces: the public square is often a place that needs to be traversed, head down, at a speedy trot rather than somewhere one might want to linger and kiss. We are often uncertain of who owns these places, what they are for.

It is this lack of sense of ownership that might explain why we feel so uncertain in such open spaces. I remember as a child being told not to go into certain play areas because they were dangerous. One often sees patches of green which should be giving a sense of delight to the neighbourhood but in fact are no more than ignored drifts of garbage. Much social housing is designed around public spaces, but there are often signs prohibiting pets or ball games, and there are regulations that no more than three youths may congregate in a certain place at any time. It is no wonder that these places become the conflicted territorial boundaries between gangs, or between youths and the authorities. It is in these vacuums, designed to enhance the environment, but which discourage sharing or ownership, that the most assaults and robberies occur. In the official reports on the 2011 London riots, much analysis was given to the lack of ‘ownership’ felt by the disaffected generation who rampaged.

In addition to this there are a number of places within the city that are being privatised without our knowledge. In January 2012 the City Corporation of London won a legal battle to evict the Occupy London protesters who had pitched their tents on the north side of St Paul’s churchyard. Before the court case there had been much debate over who actually owned the land. For many it initially seemed obvious that it belonged to the cathedral Chapter and that it was up to the Dean to decide whether to push for eviction. As a result the canon, Reverend Giles Fraser, asked the police to leave the churchyard as he was happy for the protesters to express their legitimate rights. When the Chapter decided that they wanted the protesters out, Fraser resigned, followed later by the Dean, Right Reverend Graeme Knowles. But, in fact, the question of ownership was more complex.

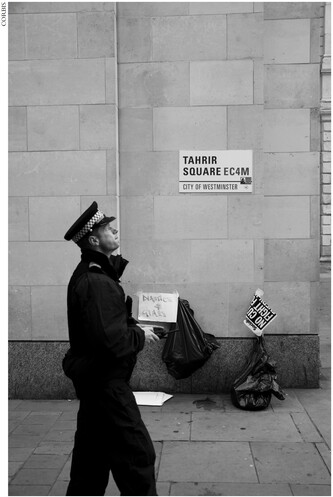

When I first visited the site in November 2011, the sense of energy and diversity of the new settlement was overpowering. I had previously written a book about St Paul’s Cathedral and had visited the churchyard on numerous occasions, but wandering around the camp was an electrifying experience. I was taken aback by how well organised and orderly the community was: there was food, together with recycling bins for all different types of waste; nearby there was a group of musicians thumping bongos and the lowing churn of the didgeridoo. By the statue of Queen Anne a soap-box evangelist was allowed to prophesy the end of the world without interruption while students in Guy Fawkes masks chatted away. There were posters protesting the imprisonment of Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan, while on the pillars of the colonnade were adverts for film-showings, debates, calls to arms, as well as scrawled, hare-brained conspiracy theories. There was a lot of wit in many of the signs, and one even made the connection between St Paul’s Churchyard and Tahrir Square.

Occupy London, St Paul’s churchyard, 2011

There was also what had been named the Tent University, home to a series of talks planned by academics, activists and even some high-profile supporters like the fashion designer Vivienne Westwood. On my first visit I slipped into the back of the marquee and listened as one speaker explained how to use social media to generate protest groups.

When I tried to walk around from the protest site, however, to nearby Paternoster Square, a place I had visited on numerous occasions, I was stopped by security guards and told to turn around. The square, part of a recent regeneration project completed in 2003, was home to a number of large offices including multinational banks Merrill Lynch and Goldman Sachs, as well as the London Stock Exchange, the target of the Occupy protesters. But I was still bemused as to why I was being stopped. My initial reaction was anger; why was I being banned from a part of my city; surely I had the right to go wherever I wanted? Apparently not; the square was not a public space at all but owned by the Mitsubishi Estate Co. It turned out that there was no public right of way and the company could grant me access or not, without explanation, whenever they wanted.

The privatisation of public spaces is more prevalent than I could ever have imagined. Not only are large tranches of the city being sold by the corporation to developers, there are also gated communities who prefer to live their lives behind electric fences. As the architectural campaigner Anna Minton explains:

Who controls the roads and the streets is, as Victorian protesters were well aware, enormously important to how cities function. Today there has been no public debate about the selling of streets at all. Instead, as ownership of British cities goes back to private landlords, the process of removing public rights of way is buried in the arcane language and technical detail of the most obscure parts of planning law . . . there is an adage in highway law which says ‘once a highway, always a highway’ . . . In many British towns and cities, this common-law right is being quietly eroded.18

It is difficult to reboot the community if our public spaces are being closed off. Where shall we meet if everywhere we go is mediated by CCTV or private security guards with hi-vis vests and walkie-talkies? At a recent talk at London’s Southbank Centre, the urban sociologist Richard Sennett, who had supported the Occupy movement since the outset, told the audience that the threat to public spaces is one of the most dangerous attacks on our civil liberties and had to be defended by any means. The audience applauded as he called for ‘more occupation of spaces’, encouraging the listeners to ‘go where you don’t belong’. It is only now, once we have lost these public spaces, that we mourn their passing.

We have become afraid of shared spaces and are inclined to ignore their importance; as a result they are disappearing without a whisper of protest. This is something that we might come to regret when it is too late. To reboot the community we need to find the spaces that we have, ‘the commons’, and make them places worth sharing.

A 2011 survey conducted by the Cooperatives UK group showed that, despite the fact that 80 per cent of people questioned said that sharing makes us happy, ‘except sharing a toothbrush’, sharing has declined over the last generation.19 The will to share exists: one in three said that they would share their garden to grow vegetables; six out of ten claimed that they would car pool if it were possible (filling the 38 million empty car seats every year) and 75 per cent agreed that sharing was good for the environment. Inevitably, however, there is a huge gulf between the will and the actuality.20 What is holding us back?

In 2009 Elinor Ostrom became the first woman economist ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize for her work, sharing the accolade with Oliver E. Williamson. Having made extensive field studies of how Swiss farmers share mountain pasture, as well as how local villages set up water-irrigation systems in the Philippines, Ostrom’s particular arena of expertise is the ‘common pool resources’, in which she has modelled the best ways to organise a local community around a finite set of resources.

It is rare that economists ever go out to observe how people actually behave and this is what made Ostrom’s research so counterintuitive. Previously it was assumed that while people tend their private property with care, they often abuse common resources with the assumption that if they did not take as much as they could, someone else would. What Ostrom observed, was wholly different: in whichever group she studied, however, the commons were looked after with the same care, if not more, as private property. What her studies show is that each community develops long-term strategies and norms of behaviour that preserve the sustainability of the resource better than any institution that can be imposed from above. A sense of ownership does not have to be exclusive in order to be real: the collective or cooperative sharing of communal property can on many occasions be the best way.

Critics might say that while this might work in a village where everybody knows each other’s business, does it work for the city? In 2011 the website Shareable.net, dedicated to promoting the cause of the commons, announced twenty policies for a shareable city by identifying the local places and activities that could have an inspiring impact.21 Working alongside the Sustainable Economies Law Center, the project strove to find the legal framework to underpin the enterprise. For example, in order to promote urban agriculture, it was suggested that the government create property tax incentives for the conversion of vacant plots to farm land; other proposals were the inclusion of ‘community gardening’ and ‘personal gardening’ into the standard zoning code; allowing commercial food farming in all city zones; subsidising water, and finally: ‘De-pave paradise and put a tax on parking lots’.22 All these initiatives could be started from the ground up by groups coming together and campaigning on a single issue in the local area. The only impediments are the will, the time and the places to plan and launch.

In addition to the commons we need places to meet up, kick back and develop the brilliant schemes that will increase our shared enjoyment of the metropolis. The city is filled with such ‘third spaces’, places supercharged to reboot the community, if only we looked harder. As sociologist Ray Oldenburg explains: the café table on the Parisian street, the English pub, the Brooklyn coffee shop where you can sit by the window for the whole day, the secondhand bookshop that offers conversation as well as the unexpected volume, the barbershop where the hours of the day are marked with banter, the candy store at the corner of Jane Jacobs’s Hudson Street, the coffee houses of seventeenth-century Amsterdam where ideas circulated like money – these informal spaces are at the heart of the community; they are the incubators and the forcing ground of society.

When I was in Paris visiting Jim Haynes’s salon, I took the opportunity to go to one of my favourite bookshops, Shakespeare and Co., situated on the Left Bank facing Notre-Dame. The shop was opened by George Whitman, who first came to Paris in 1948 under the GI Bill and soon launched himself in the literary scene. As a younger man he had travelled in South America and when he fell seriously ill, he was nursed back to health by the locals; a kindness that he never forgot.

As a result, Whitman was determined to make his shop something different, driven by the motto: be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise. And as you walk amongst the bookshelves stacked with titles in different languages, secondhand, antiquarian and fresh from the publishers, there are small beds where some of the bookshop staff rest, who have come to Paris to live the bohemian dream and are happy to find a respite where they can. This is more than just a bookstore – it is an idea, a culture, an example of how the world could or should be.

As I picked at titles in an almost random fashion, I overheard snatches of conversation: a flirting couple in the photography section; one of the shelf-stackers was complaining about another of the staff because they spent too much time on their poetry. Outside a small crowd had gathered and a man who looked strangely familiar was playing guitar with two young, grungy tourists. It was only later that I worked out that the man was Lenny Kaye, guitarist with Patti Smith and author of a book on crooners, who was doing an impromptu reading and concert.

Places like Shakespeare and Co. are highly potent spaces that draw people together and turn individuals into groups. The combination of the commons and the third place has found a particularly potent home on the internet, technology bringing larger groups of people together than ever before. While spending all one’s time on Facebook or Second Life is bad for you, technology has the capability of turning observers into actors, of aggregating interests, developing groups and coordinating community.

This mixture of networks, between the real and the digital, is particularly suited to the vast cities that will rise through the coming century. This connectedness does not mean that the electronic community replaces human contact, but the opposite: that technology can nurture a sense of citizenship, the sharing of information and knowledge, which is then taken to the streets.

The gap between the digital protest and actually making it happen in the street is the most difficult to breach. The Arab Spring was not won by people tweeting from their Cairo bedrooms but by the use of technology encouraging people out onto Tahrir Square. This relationship between media and stimulus to action is the source of great debate. For some commentators, such as economist Paul Mason, author of Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere, technology has the potential to be one of the key tools for revolution; on the other hand, writers such as Malcolm Gladwell feel these hopes are unjustified: weaks ties are not strong enough to maintain a protest.

In other spheres, the efficacy of online organising has been clearly successful, as I discovered when I visited Bangalore.

It felt as if I was on a secret mission. I had contacted the Ugly Indian (theuglyindian.com) three times from the UK before I travelled to Bangalore, but it was only once I had arrived that the group contacted me. I had an email waiting for me as I reached the hotel. I was then given a phone number, which did not pick up when I rang. Instead I got an SMS asking me to text them. Finally they gave me an address and directions for their next ‘fix-up’ the following morning. And so at eight the next morning I found myself in the back of an autorickshaw in search of a very unusual type of happening.

The Ugly Indian are an anonymous group of successful Bangalore businessmen from the IT and financial services industry who were fed up with waiting for the local government to make their city clean and liveable. As I got out at my destination, a quiet residential street in one of the toniest neighbourhoods in the city, the first thing they asked was that I not quote any names or give away any identities.

Working with the Ugly Indian in Bangalore

Already there was a group of volunteers, employees of the office block opposite, who with gloves, picks and shovels were starting to move the pile of rubble and rubbish that was overflowing from the pavement onto the road. In the words of one of the office managers, who was taking a cigarette break, for many of these educated desk jobbers, this was the first manual labour they had ever done. But as they scraped away in their weekend gear and business shoes, surgical face masks protecting them from the dust, they were already starting to make a difference. They had cleared and cemented a new, even pavement with a well-crafted kerb. They were now starting to talk about planting some bushes and perhaps flowers.

The Ugly Indian started in frustration. While I was standing there, I got talking to an older gentleman, Dr S. Janardham, dressed in a polo shirt and chinos. As well as being one of the leading IT pioneers in Bangalore, now retired, Janardham was former secretary of the HAL Second Stage Civil Amenities and Cultural Association. He told me about the neighbourhood, which was one of the first to be built as the city rapidly grew in the 1970s. The houses and streets were extremely well kept, yet there were always problems, such as the site where the rubbish was dumped and allowed to fester. As a leading light in the local association, his job was to collate a list of the trouble spots and force the local authorities to act. When I asked him whether there was ever any response, he raised his eyes to the sky and, with an apologetic smile, made it clear that my question was a bad joke. ‘What was one to do?’ he asked.

For the Ugly Indian, the solution ‘starts with the 50 feet in front of your house or your office’. The local authorities were clearly not about to change, but this did not give the ordinary citizen any excuse not to take care of the city themselves, albeit with ‘no lectures, no moralising, no activism, no self-righteous anger. No confrontation, no arguments, no debates, no pamphlets, no advocacy.’23 The project was completely voluntary, and promised nothing more than a morning or two of hard graft. Nonetheless, as one of the group that morning told me as we stopped for a cup of tea poured from a canister on the back of the bike of the chai wallah, the simple act of moving earth, clearing rubble and turning cement ‘sensitises’ the group to their neighbourhood; it showed that the ordinary citizen could organise change and take control of the places around them. Just by doing something, ‘that’ problem had turned into ‘our’ problem, which was eventually transformed into our ‘neighbourhood’.

When I finally asked how the Ugly Indian could expand and spread into other cities, the organiser looked at me and shook his head. ‘Many people ask us how they can set up their own Ugly Indian group,’ he reported. ‘I tell them that they don’t need to, they just need to get on with it.’ It seems that rebooting the community can start with the smallest of things, and the tools to revive the neighbourhood can be found all around.