6

On the late afternoon of 26 February 2012, a seventeen-year-old boy called Trayvon Martin was walking back from the local convenience store to the house of his father’s new fiancé, having bought a bag of Skittles and a can of Arizona Iced Tea. The youth, who was around 6 feet tall and in good health, was crossing The Retreat, a gated community in Twin Lakes, Florida, a congregation of 263 elegant town houses, ideally located ten minutes from downtown Sanford and the mall as well as good schools. The community was a symbol of the vagaries of development in the last years of the property boom of the noughties.

Each house – identical to the others – was built as an image of homely paradise, with a porch and a garage for one car. Inside, the future homemakers were promised the best materials and small luxuries for a hard-working middle-class family. The initial cost of an off-plan house in 2004 was $250,000. By that day in February 2012 more than forty houses were empty and over half were rented and advertised on realtors’ websites for $119,000.

The purpose of gated communities was to offer added safety and a sense of belonging but since the recession foreclosures and the rise of rental properties were making it more difficult to pinpoint who lived where in The Retreat and who was an outsider. There was no way of knowing who had the gate passcode or whether it had been handed to the ‘wrong type of visitor’. This sense of anxiety had risen along with the crime rate, which, through 2009–10, included eight burglaries, two bike thefts and three common assaults. In September 2011 the local police had set up a formal neighbourhood watch scheme in response to people’s escalating fears.

At 7.11 pm the neighbourhood watch captain, George Zimmerman, phoned 911 to report a suspicious person: ‘black male, late teens, dark gray hoodie, jeans or sweatpants walking around the area’.1 The suspect was walking with his hand within his waistband. Zimmerman was well known to the police. He had arrived at the community in 2009 along with his wife, and from the start had been an enthusiastic member of the neighbourhood watch. The list of calls he had made to 911 covered twenty-two pages and included reports as diverse as ‘Man driving with no headlights on’2 to his neighbour’s garage door being open.

At 7.13 pm, two minutes after his previous call, Zimmerman rang 911 again to report that the young person was ‘now running towards back entrance of complex’ and that he looked suspicious.3 The dispatch told Zimmerman to stay put and not pursue the suspect. Despite this command, Zimmerman expressed his exasperation that ‘these assholes, they always get away’; there is also some controversy whether he also swore ‘fucking coons’ under his breath as he followed the young man.

In the interim, at 7.12 pm, the young suspect, Martin, was called by his girlfriend. Later in an interview she claimed that he had reported someone was following him and he was scared. He began to run, about the same time as Zimmerman reported this to the police. The girlfriend heard Trayvon call out ‘what do you want?’ to someone, who had just asked ‘what are you doing here?’ She then heard a scuffle and the phone line went dead.

What happened next is contested. One eye witness, ‘John’, saw a young black man hitting another man in a red sweater who was crying out for help. Zimmerman would later claim that it was he who was being attacked. Listening to the 911 calls at the time, Trayvon’s mother attested she could hear that it was her son who was in danger. A young boy also saw a man in a red jumper on the ground, but his mother later claimed the police pressured him to say this. There was a fight, and then there was the sound of a gunshot, leaving Trayvon lying dead on the grass while Zimmerman stood over him, possibly with cuts to the back of his head. The injuries are significant, as Zimmerman later told the police he had shot the unarmed youth at point-blank range with a pistol in the chest, in self-defence.

The gates of The Retreat, Twin Lakes

After initial inquiries Zimmerman was released by the police; his later prosecution and the wider debate of police procedure, race, gun crime and the ‘stand your ground’ laws have all gained a huge amount of space on TV, radio and the news around the world. President Obama himself got involved when he stated, ‘If I had a son, he would look like Trayvon.’4 In the following court case Zimmerman pleaded not guilty for second-degree manslaughter, maintaining his claim of self-defence. Yet this is not just a narrative about gun laws, race and police protocol; it is a story about the city and trust.

It is impossible to divorce the relationship between the events that occurred on that day and the place where it happened. For not all places are the same and this has a powerful impact on how we behave, navigate and feel about the city. In 1973 the American architect and planner Oscar Newman, in a book called Defensible Spaces: People and Design in the Violent City, set out the concept of the gated community, where residents tend to feel a stronger sense of ownership or ‘territoriality’ when there are barriers. In contrast with the Broken Window idea, which sought to repair the violent city by action, Newman argued that the defensible space was a barricade to hide behind.

The idea has been hugely successful around the world, offering security, community and a sense of exclusivity. In many of the most violent and dangerous cities, urban fortresses have appeared where every movement in and out is monitored. ‘Security by design’ has become the bedrock of a securitisation industry that protects our homes using heavily armed private guards, and the latest innovations in surveillance, access control and hardware. Like The Retreat at Twin Lakes, the hi-tech apparatus and image of safety that the modern gated community promises as standard is one of the selling points of the new enclave.

The gated community is the opposite of Jane Jacobs’s exuberant, flowing Hudson Street. The self-organised complexity has been managed into order; the eyes on the street are paranoically focused on invasion. In the US, the number of such communities has grown by 53 per cent between 2001 and 2009 and now are home to nearly 10 million people. They are often built as a response to rises, or the perception of a rise, in crime beyond the fence. But while the railings may give a sense of protection, they make the city a more dangerous and unequal place. They create mental spaces that encourage the anxiety of the George Zimmermans in us all as well as define that space as outside the normal city, patrolled by private security and regulated by private committee.

If Trayvon Martin had been walking on an ordinary street rather than within a privatised neighbourhood, where he was considered a hoodie-wearing ‘outsider’, there would have been no question of invasion or property infringement. There would have been different interpretations of laws concerning carrying guns and self-defence. He would still be alive.

The line between ‘us vs them’ is redrawn within the city. While our communities should be built on a solid foundation of trust, we seem to be living in an age of increasing suspicion, distrust and fear. John Locke said that ‘trust’ was at the heart of any society; and this notion of ‘trust’ has too often been ignored in the discussions of how to make a happy city. For Jane Jacobs, trust comes from the small interactions within the street’s ballet: ‘it grows out of people stopping by the bar for a drink, getting advice from the grocer and giving advice to the newsstand man, comparing opinions with other customers at the bakery and nodding hello to the two boys drinking pop on the stoop’.5 But as the city grows, clearly these interactions can become more impersonal and brief. As our cities get ever larger, the question of trust becomes more urgent. We need to reconsider what trust is and where it fits within the modern metropolis.

You cannot see trust, you can only perceive the consequences of its absence, or the benefits of its influence. It is invisible, but it can be found in many different places: religious experience (‘trust the Lord’), as well as the scientific laboratory (‘trust your eyes’); it is to be hoped for by politicians at the stump (‘trust in me’) and with the handshake to seal the deal (‘my word is my bond’). But it can also be found all around the city, in the small transactions and interactions that we daily navigate: between individuals and amongst groups and institutions, or in the relationship between the city and the citizen. It can come with obligations and strictures on time, behaviour, reciprocity or even threat. Trust assumes an order of things, and a universally agreed norm of behaviour. But how does it work?

For political scientists like Francis Fukuyama, trust forms the bedrock of a market economy: ‘one of the most important lessons we can learn from an examination of economic life is that a nation’s well-being, as well as its ability to compete, is conditioned by a single, pervasive cultural characteristc: the level of trust inherent in the society’.6 This is illustrated by a thought experiment: a buyer and a seller decide to do a deal but agree that they will both bring a closed bag to the meeting and exchange bags without looking inside. What social pressures will encourage the buyer to put the full sum of cash into his bag? Will the merchant risk his reputation by defrauding his customer? Fukuyama suggests that a marketplace without a sufficient level of trust levies a disadvantageous reputation upon itself. In time a bourse that cannot regulate itself or honour transactions will lose its customers or have to pay a higher price to buy loyalty. The lack of trust will eventually cost a city dear.

In Fukuyama’s city, everything has been reduced to the marketplace, everything has a price and can be exchanged; one invests in order to get something out: A trusts B so that X will happen. It is trust, Fukuyama argues, that underpinned the rise of the west and could be found in the development of the rule of law in opposition to absolutism, religious tolerance which allowed every merchant to be equal on the trading floor, as well as the rise of urbanism, which was a refuge of freedom away from the obligations of the ancient regime. It is trust that formed the crucible from which seventeenth-century Amsterdam was born.

Robert Putnam, author of Bowling Alone, proposes an alternative definition of trust. For Putnam trust and sociability are connected: trust grows out of us being together, and is nurtured in the associations, bowling teams and church congregations that bind a community. Trust disappears when we spend less time with each other: ‘people who trust each other are all-round good citizens, and those more engaged in community life are both more trusting and more trustworthy’.7 Trust thus accrues social capital, a form of currency that can be exchanged and put to profit in a number of different ways. In this view, one does not trust solely because of its instant advantages, but also for its long-term benefits.

Alternatively, for the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann trust is a means of controlling the future, a sophisticated symbolic way to mitigate risk. Others believe that trust results from rights, and can only exist in places where the rights of the individual are respected. Therefore, in totalitarian states or dictatorships trust becomes a defiant act, and on occasions can even be an act of revolution. Václav Havel in the face of Czechoslovakian suppression included trust as one arrow in the quiver of the ‘power of the powerless’.

For Eric Uslaner, professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland, trust is not the result of business deals or social interaction; instead it is hardwired into our social selves, based on a basic belief in the goodwill of others. Trust came first. It is not based on a set of relationships at a certain moment – a calculation that trusting will produce benefits – but a general trusting: ‘A trusts B to do X’ is replaced by ‘A trusts’. Trust is therefore connected to optimism, confidence, tolerance and well-being, not just strategic reckoning.

This type of trust, for Uslaner, leads to social engagement rather than the negotiated results of coming together. Better cooperation then leads to the promotion of equality, policies of democracy and a belief in generalised rights. Generalised trusters are ‘happier in their personal lives and believe that they are masters of their own fate. They are tolerant of people who are different from themselves and believe that dealing with strangers opens up opportunities more than it entails risks.’8

But it seems increasingly difficult to expect to find trust within our everyday lives; this generalised trust has, for some reason, plummeted in the past decades. Most of the time the consequences are not as dire as the death of Trayvon Martin but the effects are as invidious. We have become accustomed to expect people to act selfishly, and as a result do so ourselves. This loss of trust has consequences which we can find all around us.

In 2011, following the collapse of the banks in the aftermath of the credit crunch, the revelations of MPs’ expenses in the UK, as well as the phone-hacking scandal that forced News International to admit that it had illegally listened into thousands of private messages, Ipsos MORI conducted a poll on behalf of the UK Office of National Statistics to measure levels of trust within the major professions. As expected, it made for grim reading. In response to the question ‘Would you tell me whether you generally trust them to tell the truth or not?’ here is how each profession polled:

Doctors 88%

Teachers 81%

Professors 74%

Judges 72%

Scientists 71%

Clergy 68%

Police 63%

Television news 62%

Ordinary person in the street 55%

Civil servants 47%

Pollsters 39%

Trade union officials 34%

Business leaders 29%

Journalists 19%

Government ministers 17%

Politicians 14%.9

In a similar poll conducted by Gallup in the US in 2009 there had been a drop in trust in state politicians from 67 per cent to 51 per cent.10 In 2011 the rating for the Supreme Court plummeted to 46 per cent11 while trust in the executive branch hovered at 61 per cent, the legislative branch at 45 per cent, and politicians in general were awarded a meagre 47 per cent. Some 73 per cent of the American people, however, trusted themselves to get the job done right.12 These are sobering statistics, indeed, that suggest that the relationship between the street and city hall, or the even more distant relationship between the street and Parliament, is in tatters and has been so for some time.

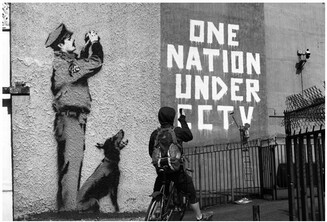

Another reflection of the erosion of trust in our cities can be seen on many street corners and high above the everyday hustle and bustle. Just as we no longer trust government, they no longer trust us. The state’s use of technology to track, watch and enumerate our every movement has become a cause for concern for many who believe that civil liberties are under threat. The most obvious example of this is the ubiquitous presence of CCTV cameras. It is not known how many units are installed in the UK but it is estimated that there are at least 500,000 in London, on average, 68.7 cameras for every 1,000 people in the capital. Thus an individual going about his business in the city is caught on camera at least ‘300 times a day’. Yet it is not just in London: it has been calculated that the remote Shetland Islands to the north of Scotland have more CCTVs than the whole of the San Francisco Police Department.13

The street artist Banksy’s One Nation Under CCTV

In Europe, CCTV is less popular, perhaps because of the legacy of fascism and stronger privacy laws. In 2004 it was estimated that, in contrast to London, there were fifteen open-street surveillance systems throughout Germany, fourteen in former Soviet Budapest, one in Norway and none in Vienna or Copenhagen.14

In the US, things changed somewhat in the aftermath of 9/11, where there was a surge in the demand for surveillance in New York in particular. In 2006 a report by the New York Civil Liberties Union calculated that within the central districts of the city, the number of CCTVs had jumped between 1998 and 2006 from 446 to 1,306 in the Financial District and Tribeca; in Greenwich Village and SoHo the number has leapt from 142 to 2,227; in total an escalation from 769 to 4,468.15 According to the geographer Stephen Graham, the city itself has become the battleground in the War Against Terror, and surveillance has become just one of the ways the state watches the enemy within: ‘Contemporary warfare takes place in supermarkets, tower blocks, subway tunnels and industrial districts rather than open fields, jungles or deserts.’16

Many of these new techniques, learnt from the battlefields and Green Zones of Iraq and the on-going war between Israel and the Palestinian people, were brought to bear in the preparations for the London 2012 Olympics. In the spring months leading up to the Games, the city was put on high alert, with the UK’s greatest mobilisation of troops and hardware since 1945: more soldiers than were stationed in Afghanistan at the same time, with an overall cost of £553 million. With manless drones circling in the air, an aircraft carrier docked in the Thames and undercover, armed FBI agents in the crowd, this sometimes gave the appearance more of a coup than a celebration. The city itself was wired with new CCTV scanners with face-recognition software, and a new central control where 33,000 screens are monitored twenty-four hours a day. Surface-to-air missiles stood on the roofs of council flats near the Olympic Village. During the Games themselves, the media gave up their usual cynical stance and embraced the occasion, even forgetting to report any of the many instances of legitimate protest that occurred. When the police arrested 130 members of the campaign group Critical Mass on the evening of the Olympic opening ceremony, few even noted the story.

The police services will go to any lengths to promise ‘total security’. But even if one agrees that it is imperative that events like the Olympics should go ahead without the risk of attacks or protest, it is sobering to consider the probability that the tight security apparatus is unlikely to go away once the carnival has moved on; as one Whitehall official commented: ‘The Olympics is a tremendous opportunity to showcase what the private sector can do in the security space.’17 In effect, the city had been turned into an emporium for the industry, and while their wares were not as obviously advertised as other sponsors, it was clearly a very important shop window. In addition, it is difficult to believe that after the vast investment made by the city in the latest technology, it will all be turned off now that the Games are over.

For many, the argument that if you are not doing anything wrong then you have nothing to fear is sufficient balm to turn a blind eye to the increased technological intervention of the street by the authorities. Only thieves and terrorists need be nervous. The evidence, however, is not so conclusive. In 2005 a report from the University of Leicester showed that CCTV surveillance had little impact on rates of crime.18 In the case of the neo-Nazi bomber David Copeland, who waged a thirteen-day campaign in 1999, there was so much surveillance around the first bomb outside a supermarket in Brixton that it took fifty detectives over twenty days to go through all the visual evidence; by the time they had finished, Copeland had already been arrested. In the end he was convicted on forensic evidence found in his bag.19

There is also a very high instance of abuse of surveillance equipment, with numerous examples of operatives using cameras to stalk women for voyeuristic purposes and to conduct illegal invasions of privacy. In particular, criminologist Clive Norris found that black youths in the UK were ‘between one-and-a-half and two-and-a-half times more likely to be surveilled than one would expect from their presence in the population’.20

Surprisingly, the evidence shows that surveillance does little to assuage the fear of crime. The 2004 report from the University of Leicester asks where was the inconclusive proof that CCTV makes people feel safer? How do we feel being silently watched by the authorities all the time? Does it change the way people behave? Does it influence our sense of trust?

In 1791, two years after the storming of the Bastille, the Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham developed the notion of the Panopticon, a prison in which the inmates were observed at all times by some unseeing eye. The design of the gaol meant that the prisoner never knew whether he was being watched or not; therefore he was forced to behave himself rather than be disciplined. In effect he became both the jailer and the incarcerated. Does CCTV have the same effect, forcing us to readjust our behaviour where we think we are being watched?

This does not just impact on the relationship between the individual and the state, but also on our relationships with each other, and with the technology companies that have become so central to our social lives. We have become very comfortable with giving our privacy away: on Facebook and Twitter, you can now locate where another poster is; in 2011 a survey by Jiwire reported that 53 per cent of mobile-phone users are willing to give away location information in exchange for content, coupons or product information.21 Smartphones have GPS and while we can use Google Maps to find out where we are, this information can be shared with others. The ubiquity of new technology creates a new layer of surveillance, which raises a series of questions that are perhaps even more urgent than the relationship between the state and the streets. As digital theorist Rob Van Kraneburg warns:

Your movements are watched, not by the use of crude cameras (which, it transpires, were rather poor at fighting crime anyway) but by tags embedded in your gadgets or in your clothes or even under your skin. Transmitted wirelessly and instantly they, connect with satellite systems that record your digital footprint endlessly. Everything you buy, every person you meet, every move you make. They could be watching you.22

Think of the different places in the city where you are not allowed to go. Consider the ‘Do Not Enter’ sign; ‘only authorised personnel allowed’. Recall the places where you need ID or are requested to sign in with security. Add to these the places that you need to pay to be in, and the ones that you have to pay to get to. There are gated communities which make sure that you cannot go inside unless you are known, and then there are the places without gates that still make it clear that you are not invited. Suddenly, the freedom of the city appears to be a maze of restricted places, streets, neighbourhoods. As a 2007 UN-Habitat report concludes:

Significant impacts of gating are seen in the real and potential spatial and social fragmentation of cities, leading to the diminished use and availability of public space and increased socio-economic polarisation . . . even increasing crime and the fear of crime as the middle classes abandon public streets to the vulnerable poor, to street children and families, and to offenders who prey on them.23

Distrust goes hand in hand with the rise of inequality, and becomes ingrained into the very fabric of the city itself. As Uslaner points out, inequality undermines the sense of common purpose and ownership, it attacks optimism and a sense of being in control of one’s fate. This is the same conclusion that Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett came to in The Spirit Level: ‘Think of trust as an important marker of the ways in which greater material equality can help create a cohesive, cooperative community, to the benefit of all.’24

In almost every statistic on the subject, however, society has been growing increasingly unequal since the 1970s, and we are only now starting to audit the consequences. This is particularly true of the city, where the super-rich and the impoverished are crammed together. Today 90 per cent of the world’s wealth is held by the richest 1 per cent. And these divisions are not just between the first and the third worlds but within our very own societies. For example, in 1973 in the US, the richest 1 per cent earned 7.7 times the amount of the average wage; at the same time in the UK, that ratio stood at 5.7. By 2008 this had increased to 17.7 times.25 London is the most unequal place in the UK: today the richest 10 per cent of the city have 273 times more than the bottom 10 per cent.

The economist Branko Milanović has attempted to calculate who was the richest person in history. Taking a measure of what an average income at any given moment and place might be, he was able to compare levels of wealth during the glorious Roman Republic, as well as the age of the nineteenth-century robber barons, early twentieth-century tycoons, to the present-day mega-billionaires.

Marcus Licinius Crassus, the money behind Julius Caesar’s bid for emperor, was said to be worth 12 million sesteres. With the annual wage of an ordinary worker estimated at 380 sesteres, Crassus’s fortune was equivalent to 32,000 people, ‘a crowd that would fill about half of the Colosseum’. In 1901 Andrew Carnegie was worth about $225 million, equivalent of 48,000 people, so was richer than the richest Roman. John Rockefeller, in 1937, had a fortune close to $1.4 billion, equivalent to 116,000 people in the years following the Great Depression and just before the Second World War. Bill Gates, in 2005, was estimated to be worth $50 billion, but despite the vastness of the sum it put him at a lesser footing than Rockefeller, with the equivalent salary of 75,000 people. But the richest man in history is the Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim who, in 2009, was estimated to be worth $53 billion – about the same as 440,000 Mexican workers. Slim’s wealth makes him almost as rich as the seventy-second largest country in the world, Belarus.26

In 2011, as the Occupy Wall Street protesters campaigned against the 1 per cent, it was sobering to note that even within this percentile there was a hierarchy. The top 0.01 per cent, comprising 14,000 families, had an average income of $31 million and accounted for 5 per cent of the total US income. The sector between the top 99.9 per cent and 99.99 per cent wealthiest in the US added another 135,000 families with an average income of $3.9 million, accumulating another 6 per cent of the nation’s total income. The remainder of the top 1 per cent – those between 99 per cent and 99.9 per cent – held another 11 per cent of the total pie, and accounted for 1.35 million families. Therefore the top 1 per cent of the US population owned 22 per cent of the whole economy.27

The city can magnify inequality: it is here that wealth is made and it is also the place that the poor come to; and often they have to live desperately close to each other. In order to measure this many economists use something called the Gini Coefficient. On a scale between 0.0 (being the most equal) and 1.0 (total inequality), one expects a developed country to be somewhere between 0.3 and 0.4, the top figure considered to be the ‘international alert line’ when levels of inequality become a global concern. Very high inequality can be found between 0.5 and 0.6 and includes countries such as Chile, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia and Kenya. Few nations – Namibia, Zambia and South Africa – chart higher than 0.6 ratio.

However, cities offer a more extreme picture than countries. In Asia and Africa, the Gini Coefficient ratios for cities are higher and growing faster than the nation, showing that just because cities are becoming richer, this wealth is not evenly distributed. This same phenomenon can be found in the US: while the national Gini Coefficient is 0.38, more than 40 American cities have a ratio of above 0.5. The most unequal city in the US – Atlanta, Georgia, at 0.57 – is at a similar level of inequality as Nairobi, Kenya, which includes the largest slum in the world, and Mexico City.28

Yet income inequality within the city is more than just a register of varying levels of wealth. The consequences of inequality go to the heart of the city: they define the urban landscape and determine the distribution of opportunities, turning the right to the city that should be available to everyone into a rigged lottery. In an unequal city it is more difficult to get access to housing, healthcare, education and transport. Inequality is connected to higher crime and murder rates, a reduction in social mobility and the decreased likelihood of voting in an election. It also results in increased levels of mental-health problems, teenage pregnancies, obesity, poor exam results, and, most perilous of all, it lowers life expectancy.

When I lived in Santiago de Chile in the 1990s, I only went once to the Pudahuel commune that stands on the outskirts of the city, close to the airport. There seemed to be little reason to go there, one of the city’s forgotten corners. Today hotels and convention centres have been built that are easily accessible from the terminus and highways that take you straight into the centre of town, giving the impression that this is a successful neighbourhood. However, there is another story that is hidden behind the shiny glass and well-tended forecourts of the business zone.

Pudahuel was first a shanty town that grew out of the rapid urbanisation of Santiago in the 1960s, when the government could not cope with the level of migrant workers flooding into the city. During the presidency of the left-wing Allende, places like Pudahuel became centres of radicalism and hope, and were therefore crushed when the military dictator Auguste Pinochet stole power in a coup in 1973. As well as torture, secret police and martial law, Pinochet used the city itself as a means to control the masses: those who supported him were rewarded with lucrative development contracts, as well as the opportunity to make a fortune in the privatised utility markets. For those who opposed the military regime, life became very difficult. Pudahuel was purposefully allowed to rot, denied services and overlooked for any development projects.

As a result, in 1983 the neighbourhood erupted in a series of protests against the lack of housing, including hunger strikes and illegal rallies as well as occupying embassies to gain international attention. Wanting to set an example to the other ‘red’ poblaciónes who dared to complain, the authority’s response was brutal and ten locals were killed. Afterwards the regime continued to use the right to the city as a means to suppress the people: the housing market was opened up to speculators who saw profit in many of the regions of poor housing close to the centre, leading to brutal slum clearances and widespread movement of the poor away from the richer neighbourhoods.

When the regime ended in 1989, the new government continued the existing vision of the city by clearing the poor out of the centre of the metropolis and creating new under-developed communities at the periphery of the city where cheap land was available. There was no will and few funds to improve the poor neighbourhoods where they stood and by 2000 Pudahuel was the third poorest commune in Santiago, with over a third of the population living under the poverty line. One of the key problems that many commentators highlighted was not that there were no jobs, but that access to work was so difficult: people in the población could not travel into the city because there were no reliable services to deliver a ready workforce to the workplace.

In 2006 Marisa Ferrari Ballas conducted a survey into the problems faced by women who live in Pudahuel as they travel by public transport around the city.29 She noted that while there had been improvements to the transit system in Santiago, these had mainly been aimed at servicing the richer parts of the city. Where the need was greatest – amongst the poor who had to travel the furthest and had the least income to pay – improvement had been slow. For some families transport costs to work could account for as much as 30 per cent of the weekly income.

Ferrari Ballas then measured the time spent on transit, revealing that 25 per cent of all women questioned spent over two hours a day riding to work, while nearly 75 per cent lived at least an hour away from the office or workplace. In addition it was revealed that many women felt unsafe on the bus, and were compelled to stand, holding their shopping and their children for long periods of time. From this study alone the case for safe, regular and well-maintained transit is compelling and could have a huge impact on the equality of the city; but it is too easy to overlook the plight of the silent and the invisible.

The problem of access to the city is shown in even more stark contrast when considering the Hukou system in China. In March 2003 Sun Zhigang, a 27-year-old graduate and a worker at the Daqi Garment Factory in Guangzhou, southern China, died suspiciously in the medical clinic attached to one of the city’s detention centres. Sun had arrived in Guangzhou three weeks earlier and on the morning that he went missing had left his flat to visit an internet café. At the door he was stopped by the local authorities who asked to see his papers, including his temporary permit to work in the Hubei province and his ID card. He had not yet applied for residency, and his permit still indicated that he was a resident of his family home in Hubei. He had forgotten his ID but offered to call a friend to bring it to the shop.

After that, nothing was heard of him until a friend called his family to let them know that he had been found dead. The following day, Sun’s father and brother arrived from Wuhan to identify the body, and were told that he had died of a brain haemorrhage and heart attack. At a later autopsy conducted by experts from Zhongshan University, anomalies started to pile up. They reported that Sun had died from injuries and traumatic stress; it turned out that he had been beaten across the back. The family took the controversy to the Southern Metropolitan Daily newspaper, but there was little reaction as the current SARS epidemic was monopolising the front pages. Instead, an internet campaign started, calling for justice for Sun. In the end, twelve employees of the detention centre were convicted for the crime.

However, the issue was not just the story of brutality against a student. As the news started to spread through the internet some academics also began to question the legal issue of the Hukou system, which was the reason for Sun being detained in the first place. The system had a long history in China but had most recently been revived in 1958 as a way to regulate the flow of immigration between the countryside and the city. In that year Chairman Mao had called for a ‘great leap forward’, with the hope of transforming China from an agrarian economy to an industrial giant in an instant.

In Mao’s dream private farms were to be collectivised and the country would benefit from the increase in productivity: this would then feed a policy of rapid urban industrialisation. Except things went desperately wrong. In the cities, steelworks and industrial factories become the property of the state and there was a rapid rise in production in the first year. However, there was not enough grain to feed the workers, as the collective farms failed to fulfil demand; Mao decided that it was the rural farmer who would suffer the most and the ensuing famine and deprivation was widespread. The Hukou system was enforced to keep the rural workers in the countryside, although they could not survive there; only holders of the right papers were given food in the city. In the end, it is estimated that up to 45 million people died of hunger as a result of the policy.

In recent years the Hukou system has been used to restrict movement from the countryside to the city to share in the economic boom of the new economy. It has created a whole class of illegal workers, who have no rights or papers, ready to be exploited by the factories. Today nearly 200 million workers live outside their legally registered territory and therefore cannot expect any government services, healthcare or education. While they earn wages in the factories, they cannot gain resident status. Instead, they remain informal labour, threatened with expulsion. In addition to this illegal workforce there is an added 130 million ‘home-staying children’, as they are called, the next generation of workers whose lives are already blighted by this inequal policy.

There have been numerous calls to reform the system. Following the horrific death of Sun Zhigang, the process of C and R (custody and repatriation) was repealed, so the brutal treatment meted out to illegal workers was no longer possible. In 2005 there were news reports that the system was to be wholly abolished but there has been little more reform than devolving responsibility for regulation from the central authority to local government. This allows Beijing to blame the regional cities when things go wrong, but the cities are not keen to abolish a policy that would force them to provide services to an unknown new population. Instead, at any moment there are 40 million Chinese people flowing between the cities and the countryside, unaccounted for, unprotected. Today, workers don’t fear being picked up by the authorities, they are just ignored.

When the recession hit the globalised markets in 2009, most of the headlines pointed to China’s resilience and the bold new future for the Chinese economy, but this hid the terrible impact that was felt amongst the migrant workers who were not part of the economic boom. They would never become members of the Chinese middle class, sharing the spoils of the nation’s fortunes, because they had been born in the wrong place.

In 2010 the American journalist Leslie T. Chang went to Ghangzhou and spoke to a group of factory girls who had come to the city, having paid a couple of recruiters who promised them jobs, and worked with borrowed ID cards and new names. They all started work on the assembly lines but hoped to move quickly up the factory hierarchy, never to return to the countryside. They slept in dormitories, sometimes twelve to a room. The rules were strict within the factory: no talking, ten-minute bathroom breaks, and numerous systems of fines and punishments. The risks are high but for many worthwhile: one earns enough to send some home to the village, one can also work hard, strike lucky and cross the class divide, get an education and become a member of the middle class. But for most, the threat of discovery, unemployment and desperation remain.

According to Kam Wing Chan, professor of geography at the University of Washington, the Hukou system has made impossible the development of the Chinese middle class. Shenzen, with a population of 14 million, has only 3 million registered urban dwellers. It is this very fluidity and informality of the labour market that has allowed the economy to grow so quickly: ‘This system of official discrimination has enabled China to experience such economic growth – and what makes it unlikely that the second-class citizens will be able to become the sort of consumerist middle class outsiders are predicting.’ In the long term this means that China will remain a nation of home-grown illegal immigrants, and cannot develop the domestic market to consume its own products. For 140 million (over twice the population of the UK), sharing the urban dream is impossible.30

Can we rebuild trust, or is it lost forever once it disappears? Is it a political question or can we design equality into the fabric of the city? Can we organise ourselves to rediscover our sense of community?

Sometimes the most pertinent observations come from unlikely places. More than any other section of the city, taxi drivers understand the way the urban world works. It is for good reason that the test every London black-cab driver must pass is called ‘the Knowledge’. In a recent study amongst taxi drivers in segregated Belfast, blighted by decades of religious violence, the report stressed how important it was for the drivers to understand the human cartography of the city as much as the street map in order to stay safe.

One of the most unexpected taxi drivers in history was the French Marxist philosopher, famed resistance fighter and radical writer on the city, Henri Lefebvre. In his essays, Existentialism, he looked back on the influence that his job had on formulating his ideas. Having come to an impasse in his life, he had stopped working, given up on his latest manuscript, and broken from his philosophical comrades. He continues:

I became (of my own free will, O champions of liberty) a manual worker, and then a taxi driver. And that really was a laugh. A huge volume could not contain the adventures and misadventures of this existential philosopher-taxi driver. The Paris underworld unfolded before him in all its sleazy variety and he began to discover the secrets . . . I want to remember only my contact with the infinitely more precious and more moving reality: the life of the people of Paris.31

David Harvey, one of the leading explicators of Lefebvre’s work, concludes that this period behind the wheel ‘deeply affected his thinking about the nature of space and urban life’.32 Some years later, in 1967, Lefebvre published his essay ‘La Droit de la Ville’ which proposed that while the city was the place where inequality, injustice and exploitation were most apparent, it was also the site of its transformation. The city causes the crisis – the home of neo-liberalism, the banking community, hideous inequality – but also offers the best possible location for its salvation. Only the city could cure the city of its own ills, but this future could only come from the bottom up.

For Lefebvre, the ‘right of the city’ is ‘like a cry, and a demand’.33 In particular, the citizen has a right to participate in as well as to appropriate the city: that is to say, the people should be at the heart of any decision-making process about the creation and management of the city; as well as having the common right to use and occupy the spaces of the city without restriction. The emphasis on the physical spaces of the city being the theatre for everyday life, Lefebvre argues, changes our sense of belonging. Being part of the city is not determined by ownership or wealth but by participation, and in consequence our actions change and refine the city.

Yet Lefebvre’s philosophical observations do not offer a map; rather they are an appeal to study and re-evaluate everyday life and examine how inequality shows its face in many different ways. Rather than policy, he offered the hopes of the city liberated from its shackles. A few months following the publication of his essay, that hoped-for revolution appeared to have exploded in Lefebvre’s own city of Paris. In May 1968 protests broke out in the capital as students, trade unions and political activists took to the streets and demanded change from the conservative rule of Charles de Gaulle. Many felt that this was the moment when Lefebvre’s vision of the city might come true.

But despite the failure of 1968 to deliver on the promise of revolution, the idea of ‘the right to the city’ has remained a potent hope.

The advantages of ‘La Droite de la Ville’ being a philosophical essay rather than a political road map has meant that the concept has been refreshed and refined by subsequent thinkers and campaigners. It was there at the Occupy camps in cities around the world, in the concept of taking public space and transforming it through their actions. As the American legal activist Peter Marcuse blogged, there was a strong connection between 1968 and Occupy: ‘The spirit of 1968 has continued and is part of the DNA of the Occupy movement and the Right to the City movements . . . both reflect the underlying impetus for change, the congealed demands of the exploited, the oppressed, and the discontented.’34

Some cities have already adopted the idea of the right to the city as an expressive part of their constitution. For example, the 2001 statute of São Paulo states that each citizen is guaranteed ‘the right to sustainable cities, understood as the right to urban land, to housing, to environmental sanitation, to urban infrastructure, to public transit and public services, to work and to leisure, for present and future generations’ (although this does not seem to have changed the everyday life of the city, which is one of the most inequal in the world). Similarly, Argentina’s third city, Rosario, has declared itself a ‘Human Rights City’. In 2004 this idea was enshrined at the World Urban Forum in Barcelona in a World Charter of the Rights of the City that hoped to anatomise in articles and clauses the poetry of Lefebvre’s philosophical position.

The fight for the right to the city is perhaps most obviously seen in the issue of housing, which was at the heart of the recent economic boom and subsequent bust in 2008. It was the subprime market and the massive extension of debt that allowed the market to ‘privatise profits and socialise risk’. The basic need for housing was conjured into the dream of a family home obtained by a mortgage that was easy to negotiate and impossible to pay off. When the market was good, driven by spiralling demand as everyone was told that they could share the home-owning utopia, it was possible that your house was earning more than you were. Your house was no longer a home but a speculative commodity that you happened to live in. Inevitably, when thousands found that they could no longer make their monthly payments, this confusion collapsed with hideous consequences.

To take one example of a country affected by the housing market: between 2000 and 2006 house prices in Ireland doubled; and 75,000 new homes were being built every year to supply the demand. Much of this was encouraged by a keen mortgage market that was willing to take greater risks than ever before in order to fill the order books. In 1994 banks and building societies advanced 45,000 loans to a total sum of €1.6 billion; in 2006 lenders were willing to give out 111,000 loans worth €25 billion. In addition, those who applied for loans were changing. In 1997 only 4 per cent of loan applications came from ‘unskilled/manual’ workers; by 2004 this had risen to 12 per cent.

At the height of the boom some houses in Dublin were worth 100 times the owner’s salary. But then, in 2007, the market began to slow and there were rumours of problems on the horizon; yet estate agents, economists and politicians continued to tell people to buy. The crash eventually came in 2009 and by the end of 2010 over 31 per cent of all properties were estimated to be in negative equity. Today there are large areas of Dublin that remain half-finished building sites, while other neighbourhoods and new developments stand empty.

The idea of a home in the suburbs (despite the unserviceable mortgage), of the security of living in a gated community, has long been at the heart of the contemporary dream, and, as events have shown – the empty neighbourhoods of Detroit, the death of Trayvon Martin, the increasing levels of inequality within the city – this dream has turned for many into a nightmare. There are now deserts of empty speculative homes in almost every city that was swept up in the boom years, while nearby thousands of people are desperate for proper housing.

In May 2010 the New York chapter of the Right to the City Alliance produced a report that gathered together the results of an eight-month survey conducted through seven neighbourhoods within the city – South Bronx, Harlem, West Village, Chelsea, Lower East Side, Bushwick and downtown Brooklyn – in order to calculate the number of vacant buildings or lots that could be used for housing low-income families. At that time it was estimated that 400,000 individuals were currently living in homeless shelters, including families and children; elsewhere 500,000 households were in rented accommodation but their housing costs accounted for more than 50 per cent of their monthly income.

The report found that a total of 450 residential buildings were completely empty, offering housing for an estimated 4,092 families. It also found that a further 3,267 units were under construction. Meanwhile, a large proportion of new luxury units being built in these neighbourhoods were being sold at a price outside the reach of the average resident. Many apartments had been for sale for months, empty and without a buyer able to afford the inflated price. In the meantime, the city government was chasing over $3 million in tax arrears from developers who were late or could not pay.

A similar injustice became apparent in April 2012 when Newham Council in the East End of London, the locale of the £9.3 billion Olympic Park, sent out letters to 500 families in local social housing informing them that they had to move out of London and relocate to the city of Stoke over 160 miles away. Months before, as part of the government’s austerity measures, a cap on all housing benefit had been imposed which made it almost impossible for London’s most needy to live in their home city. At the time, London mayor Boris Johnson caused controversy by calling the measure similar to Kosovan-style ‘ethnic cleansing’. When the news was announced, 350,000 were sitting on the housing waiting list for the whole city. Homes for London, the project set up by the charity Shelter, calculates that 1.8 million people will be pushed out of the city as a result of rising rents and the cap.

Homes for London also calculated that 33,100 new homes need to be built every year, but the evidence on the ground is woeful. When he was first elected in 2008, Mayor Johnson called London a ‘first-class city with a third-class housing system’, adopting the policy of his predecessor Ken Livingstone and promising 10,000 new units every year to accommodate the continued rise of demand for assistance within a hyper-inflated market. Yet even at this rate, it is not sufficient. ‘Affordable housing’ itself is a term that can be interpreted in different ways, with the official definition pegging it at 80 per cent of market rate, and therefore still out of reach of the most needy. As rents rise ahead of the inflation rate, increasing by 11 per cent in 2011 alone, homelessness seems the only option for many.

The survey in New York and the news from London both reveal how far our major cities are from adopting the right to the city as one of the cornerstones of a modern metropolis. In the aftermath of the 2008 housing crash, the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University, New York, published The Buell Hypothesis, which investigated the relationship between housing and the American Dream in the face of mass foreclosures. The report pronounced a succinct but radical conclusion: change the dream and you change the city. In this scenario the right to the city is not the right to a suburban house, a car and an impossible mortgage; instead we need to redraft the dream: the right to live and have access to the things that make urban life worthwhile: an affordable home, a reasonable wage, freedom from intrusion, harassment or violence. As we consider these questions we must look at the visible and invisible barriers to the city: for the young, the disabled, the disadvantaged and the poor, the old and infirm, the foreign and unfamiliar.

One possible way of engaging with this question was proposed by David Harvey in a lecture given in 2008 at the City University of New York Grad Center. Here, Harvey suggested that the right to the city offers a way to talk about the neighbourhoods and the communities that have been excluded and exploited by inequality. In particular, he stressed that the right to be part of the city should not solely be determined by the ownership of property alone. During the housing boom, he argued, it was only the desires of homeowners that mattered. As a result, those who do not own property, or those who cannot afford a deposit, have no stake in the city.

In response Harvey offered a simple solution that could be found in the ruins of the housing collapse itself. Following the 2008 credit crunch where so many homes were foreclosed because of the owners’ inability to pay the mortgage, families lost everything and were forced to move away while the bank got little back on their investment. But this makes little sense – it ruins families, destroys communities and weakens cities. If the banks and municipalities were able to rethink this situation, a more hopeful future was possible. For example, the city could buy the property from the banks at a good price, creating manageable housing cooperatives, guaranteeing that families can stay where they are and maintain their participation in the life of the city.35

Consider this scenario in the case of Detroit, which today faces the crisis of ‘right-sizing’ as a result of the death of communities driven away by foreclosures, leaving large tracts of the city empty and ripe for decay. Mayor Bing now finds himself in a situation where he is forced to spend millions to provide services to neighbourhoods that are barely there, and he is not able to collect civic taxes from the absent citizens who have left. If, at the outset, efforts had been made to socialise housing and keep the community together, the bill would probably have been balanced and the neighbourhood strong enough to face the future. In addition, this would have helped to increase the right to the city and equality, and built a city based on trust. For if the city is not good for all, it is not good at all.

But can we design trust, just as we can design and model other behaviour in the city? I asked this question of urban strategist Scott Burnham as we sat on the fifth floor of the Royal Festival Hall, overlooking the south bank of the Thames. Looking northwards towards the heart of London, the impressive skyline was a reminder of the capital’s history, sweeping from the Houses of Parliament in the west towards St Paul’s Cathedral and the City in the east. Many of the most prominent buildings were monuments of past glories, imperial grandeur, as well as the capital’s continuing economic power. The Royal Festival Hall itself tells another story, for in the aftermath of the Second World War it was decided to stage a festival that would bring hope once again to the nation. Thus, in 1951, the Festival of Britain was held in previously ignored industrial wasteground on the south bank, to promote a new post-war future rather than a fanfare for previous national superiority and tarnished pomp.

The whole site was transformed in the hands of a fresh generation of modernist architects who wanted the new style to represent an optimistic future, as designer H.T. Coleman noted: ‘There was a real sense in which the Festival marked an upturn in people’s lives . . . it was an event for a new dawn, for enjoying life on modern terms, with modern technology.’36 The Festival Hall is all that remains of that event, a reminder of former dreams as well as one of the most popular places in the city today for everyone from classical music fans to skateboarders. Looking across the river, it seemed appropriate to talk about whether ideas and stones can help revive a sense of trust in the city, just as it had done with the nation’s sense of hope and renewal five decades ago.

Scott Burnham has travelled around the world working on projects with designers, architects and cities, hoping to make people look at urban spaces differently. In particular he is passionate about exploring ways that city design can enhance and nurture trust. Yet his reading of what trust is is different from that of Uslaner; rather he believes that everyone has a set quantity of trust which is constantly being redistributed according to experience and circumstances. The fact that we no longer trust politicians and the police means not that we have lost trust but that we have placed our trust in other relationships and forms. Rather than signalling the end of trust, instead what we are seeing is its redistribution into other systems such as the proliferation of open source and sharing communities – what Burnham calls a ‘sharing economy’. As a result, as hierarchical trust has declined, a belief in the commons has become more important, as we ‘discover new values, and new ways of creating and extending trust, outside of existing damaged systems’.37

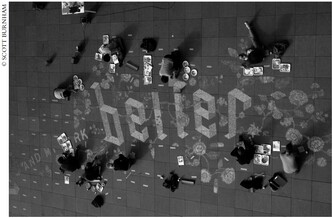

The Sculpt Me Point exhibit by Marti Guixe, Amsterdam, 2008

But, I asked, how does this reflect on the way we build cities? He then told me about some of his previous projects. Between 2003 and 2006 he was the creative director of Urbis, the centre of urban and popular culture in Manchester, where he held exhibitions on street art and the work of leading designers such as Peter Saville and architect Will Alsop, which set out a vision of Manchester as a twenty-first-century mega-city. In 2011 Burnham was also involved in the innovative Urban Guide to Alternative Use project in Berlin that encouraged people to rethink how they used the everyday objects of the city. Therefore, with a simple piece of plywood and some chairs a series of bollards became an outdoor café; a municipal wheelie bin became a pin-hole camera; a rotating billboard transformed into a carnival swing. All these projects reminded the user of the flexible and adaptable nature of the city’s fabric for fun or the joys of civic life, reinventing urban spaces as places of play and the unexpected.

In 2008 Burnham created a specific project for the IJ Waterfront neighbourhood in Amsterdam, which at that time was being converted from a run-down industrial sector into a more lively residential and work zone. Part of this transformation was to encourage people to think about the area differently, to visit and enjoy the improved public spaces. Burnham, alongside the leading Dutch design team Droog, developed a series of features and events that encouraged the visitor to interact with the exhibits; as he describes: ‘The IJ waterfront area of Amsterdam was transformed into a creative playground where people could interact, alter and rework a series of design installations. To use a software analogy, the designs were installed in version 1.0, and it was up to the public to develop them into version 2.0 through individual and collective creative intervention’.38

The variety of events and exhibits came from an international gathering of artists and designers: the Nothing Design group from Korea set a series of fish-shaped wind vanes on poles along the river front. Each pole could be adjusted in height, and turned so that it filled and fluttered in the wind depending on the direction in which it was pointed. The international Office of Subversive Architecture created a sand box so that participants could create their own cities. Ji Lee produced a bubble project allowing users to print off their own blank speech bubbles that they could then fill in and place upon advertisements around the city, thus challenging the corporate message and the commercial dominance of public space. Potentially the most problematic entry in the exhibition was Marti Guixe’s Sculpt Me Point, which saw a large structure of concrete breeze blocks left in the middle of the street, to be used by passers-by any way they wanted.

As Burnham described, his apartment window stood opposite the exhibit and initially he watched as people started by scratching swearwords and rude symbols into the surface of the concrete, as if the shock of being allowed to do whatever one wished forced one to deface and rebel. This is how we expect everyone to behave if we give them the freedom to do what they want, Burnham explained, but almost immediately, there was another impulse and he watched as a group of young skateboarders came along and spent a number of hours working together spontaneously on carving an elegant elephant into one of the faces of the block.

Obsessions make my life worse and my work better by Stefan Sagmeister, before it was tidied up

Perhaps one of the most surprising reactions to the exhibition came from the police, a reminder of the difference between authority and trust. One of the main exhibits, devised by the artist Stefan Sagmeister, was a street collage using 250,000 Euro cent coins, which stretched across a street in a swirl that spelt out the phrase ‘Obsessions make my life worse and my work better’. Both Sagmeister and Burnham had purposefully left the collage open to the public so that they could interact with it as they wanted; if they lost some coins, they concluded, so be it. The police saw it in a different way and within twelve hours of the opening of the exhibition it was reported that there had been a theft. By the early morning they were sweeping up the coins and putting them in bags, informing the organisers that they had ‘secured’ the work.

So where was the trust in all this? Clearly people had come to the exhibition and interacted with the objects and perhaps even started to think about public spaces in the city a bit more. Certainly it encouraged people to think about the space – the IJ Waterfront – in different ways. It may have also allowed people to think differently about the potential for spaces within the city, as well as offering a reminder that sharing and finding common spaces helps people to get along. But does this build trust?

According to Burnham, it does. While Putnam put an emphasis on formal participation and association as the bedrock of trust, Burnham suggested that the simpler and less organised interacting on common ground was a powerful enhancer of togetherness. Events that could have incited and encouraged uncivil behaviour in fact nurtured the very opposite. Trust was allowed to express itself spontaneously. Yet more importantly than this, Burnham reminded me that trust was not a building, it was not bricks and stones; instead it was the sharing of the process of building that created and nurtured trust.

That we no longer trust governments, corporations and police does not mean that we have lost the art of trusting. We are already more trusting than we imagine in a new sharing economy that encompasses car clubs, Airbnb; World Book Night; peer-to-peer platforms; Wikipedia; Instagram; open source software such as the Linux operating system and the Firefox browser, as well as the Creative Commons code of practice.

However, we need to be aware of how the uses of urban spaces can impact on this. We need spaces that allow us to be ourselves. We do not necessarily have to build new places in order to create these trusting spaces, we need to have open, public spaces where we can behave and interact in trusting ways. Gates, surveillance cameras and empty condominiums, at a time when there is such a housing need, a problem with access to work and poor infrastructure, stand in opposition to the open city that is the right of everyone.