8

When the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations opened in May 1853, on Reservoir Square in New York, it caused a tourist boom: over 1 million visitors paid the 50 cents entry fee to wander the crystal halls in which the varied goods and wealth of the modern world were displayed. Inspired by the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, the Palace glistened in the Manhattan sunlight, constructed from 15,000 panes of glass and 1,800 tons of cast iron, and topped by a 100-foot-wide dome which rose 123 feet above the city. Nearby stood the 315-foot-tall tall Latting Observatory from where the crowds could look out across the skyline as far as Staten Island and New Jersey. The whole exhibition showcased the many wonders of the thrusting modern city to awesome effect.

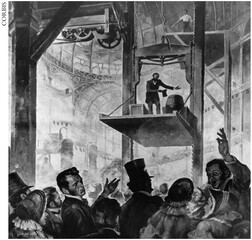

Each day a crowd gathered in one of the main halls, huddling in front of a stage upon which stood a structure that appeared at first glance like a gallows. As workmen took the strain, pulling the ropes taut, a platform rose bearing aloft the inventor Elisha Otis, accompanied by several barrels and heavy boxes, until it reached 30 feet above the heads of the throng. After a dramatic pause an assistant cut the hoists with an axe and the crowds gasped as they anticipated seeing the engineer crash to the floor. But the platform only dropped a few inches and remained there, suspended in the air. It was held by Otis’s patented device, the ‘safety hoister’, a serrated brake that activated in emergencies by gripping the toothed guide rails running the length of the lift shaft. Above the murmur of astonishment, Otis announced to his stunned audience, ‘All safe, gentlemen, all safe.’ It was a spectacle that heralded a new age in the history of the city.

Otis’s story is a forceful reminder of the connection between creativity and the city. He had been born on a farm in Halifax, Vermont, in 1811 and, after leaving home without qualifications at nineteen, had turned his hand to numerous ventures: he had worked as a builder in Troy, he built a gristmill on the Green River, constructed carriages and wagons, but nothing seemed to bear fruit. After a bout of illness he then moved to Albany where he found employment at the Tingley Bedstead Factory as a mechanic and rail turner. It was there that he developed his idea of a ratchet device that could hold a platform in place if the pulley system broke. His new invention made safe the raising of heavy machinery on the workshop floor. After setting up his own office, a few orders started to trickle in, enough to persuade Otis not to leave the east coast and join the Californian gold trail. But his fortunes really changed in 1854, when the impresario P.T. Barnum paid Otis $100 to display his latest invention at the Exhibition in New York.

The elevator was nothing new: it had been in use since the days of the Romans, but what Otis had done was to make it safe. Within a year of the Exhibition, Otis was swamped with orders; in 1854 he turned over $2,975, only to double his profits the following year. It was not until 1857, however, when an elevator was installed in the ‘the greatest china and porcelain house in the city’ – E.V. Haughwout and Co. on Broome Street and Broadway – that the Otis Automatic Safety Device was used for human passengers. As Elisha developed his company with his two sons, Charles and Norton, they continued to improve the design, soon offering a steam-powered lift that rose at a steady 0.2 metres a second (today, the fastest elevator in the world in the Taipei 101 Building travels at 1,010 metres per minute, rising 101 floors in thirty-nine seconds).

Despite Elisha’s death in 1862, the Otis Elevator Company flourished and by 1870 there were 2,000 steam-powered contraptions in operation. That same year it was calculated that the new lifts installed at Lords & Taylor on Broadway had carried over 10,000 shoppers up and down five floors within the first three days of operation. By 1884 the company had opened an office in Europe and was providing elevators for the Eiffel Tower, London’s underground stations, Glasgow Harbour, the Kremlin and even Balmoral Castle. Today, more people in New York travel via an Otis elevator than by any other form of public transport.

A reimagining of Otis’s performance: ‘All safe, gentlemen, all safe’

Before Otis, there were few places where buildings were constructed taller than five storeys. It was as if the world had heard Julius Caesar’s edict that no building in first-century Rome should rise higher than 70 Roman feet (later reduced to 50 feet by the Emperor Nero) and had never wondered what it would be like to build upwards into the air. Only in Sana’a, the capital of the Yemen, did some of the traditional mud tower houses teeter precipitously up to eight or nine storeys.

All that changed in the 1870s, when a combination of steel-frame buildings, stronger than brick or stone, and Otis’s elevators allowed architects to dream of new kinds of cities. So in 1885, the ten-storey Home Insurance Building was opened in Chicago and named the world’s first skyscraper, with its architect, William Le Baron Jenny, proclaiming that ‘we are building to a height to rival the Tower of Babel’. Then, in 1902, the Flatiron Building was opened in New York, containing an Otis steam-powered elevator rising to all twelve floors. Within a decade, the Woolworth Building had scaled fifty-seven storeys; and in 1930 the Chrysler Building topped out at seventy-seven floors. Currently, the tallest building in the world is the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which rises to 160 levels.

New technology, such as Otis’s elevator, offers us the tools to transform the city. Technology drives the way a city works, and the way a city is built; it determines the maximum size that a city can grow and who lives there, the complexion of its human capital. Friedrich Engels gives a vivid portrait of the industrial city, Manchester in the 1840s: ‘The degradation to which the application of steam-power, machinery and the division of labour reduce the working-man, and the attempts of the proletariat to rise above this abasement, must likewise be carried to the highest point and with the fullest consciousness.’1 This was the diagnosis of the city driven by the steam engine; the industrial metropolis of the age of coal that forced workers into factories, and reduced men into mechanical parts.

In a similar fashion the post-war era was an age propelled by the technology of the automobile that delivered a new kind of city, pushing its outer limits ever further, continuing the trends first set by the trains and tramways of the Victorian metropolis. The city had already been divided; the city centre had become the public sphere in opposition to the domestic bliss of the suburbs, and was further divided into business districts, industrial zones and business parks all linked by asphalt so that one could avoid experiencing the city at all. This was the city dreamed by Le Corbusier and Robert Moses: an efficient, rational machine. Today, we are living in the consequences of this vision: empty streets, congestion, obesity and disconnected neighbourhoods.

While the industrial age was transformed by factories and trains, today’s city is redrawn by the mobile phone. Modern technology offers an alternative way to rethink the city where the internet, computing and ubiquitous data transform the places where we live as well as how we work. How can the phone in your pocket improve the world? How have the things that we now take for granted – text messaging, social networks, sat nav – changed the lives of millions? We are at the beginning of a new urban era in which technology can create smart cities, where information can regulate the metropolis. Perhaps this latest era of technology offers the key to the true potential of the city.

In parts of Nigeria, the mobile phone is called oku na iri, ‘the fire that consumes money’; nevertheless this simple piece of equipment has had a huge impact on the developing nations of Africa.2 Since 2000, the rapid escalation of mobile technology across the continent has been extraordinary: in 1999 only 2 per cent of the total population had access to mobile phones; by 2010 this had risen to 28 per cent; adoption has been at twice the speed found elsewhere in the world, growing at approximately 45 per cent a year. For many in sub-Saharan Africa where there is less than one fixed phone line for every 1,000 people, this does not mean that people are choosing one form of technology over another; for some, this is the first time they have ever had access to a phone at all. As a result:

In Mali, residents in Timbuktu are able to call relatives living in the capital city of Bamako – or relatives in France. In Ghana, farmers in Tamales are able to send a text message to learn corn prices and tomato prices in Accra, over 100 kilometres away. In Niger, day labourers are able to call acquaintances in Benin to find out about job opportunities without making the US $40 trip. In Malawi, those affected with HIV and AIDS can receive text messages daily, reminding them to take their medicines on schedule.3

In 1999 there was only mobile coverage for approximately 10 per cent of the continental population, and most of these were in the main cities of the northern African nations and South Africa; by 2008 this had increased to over 60 per cent (95 per cent in north Africa, 60 per cent in the sub-Saharan region), a total area of 11.2 million square kilometres, the combined size of the US and Argentina. Coverage was first rolled out within the major city centres but quickly included many rural regions, connecting the villages with the main regional markets and beyond. In villages in Uganda researchers found that even in places without electricity, many people had fully charged handsets, and had used their phones in the past two days; this revolution encouraged the president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, to comment that: ‘In ten short years, what was once an object of luxury and privilege, the mobile phone has become a basic necessity in Africa.’4 It has also proved to have an impact on economic growth; in a study of twenty-one OECD nations, a 10 per cent rise in telecommunications penetration resulted in a 1.5 per cent rise in productivity.

This productivity comes in many different forms. The business of telephony itself creates a market in handsets and a network of sales agents, from official outlets to the informal economy where card shops and repair workshops proliferate; it also offers new opportunities to the ordinary worker: the connected network saves money and reduces transportation costs, particularly saving the money and time expended searching for employment. It allows for the exchange of market information so that consumer prices are regulated. Within companies information can also be used to coordinate the supply chain, avoiding shortages or overstocks. In certain markets this has clear benefits: in the grain markets of Niger, being connected can have a nearly 29 per cent impact on profits over a year.

Kenya offers an example of how the mobile phone has been transformed from status symbol to vital economic tool. In 1999 Safaricom, the nation’s leading mobile operator, estimated that by 2020 there would be a total of 3 million handset users; by 2009 they were coping with 14 million on their network alone. At first the swift adoption of mobile telephony was a reaction against the old ways of doing things. When many firms could expect an average of thirty-six days a year of interrupted fixed-phone network, often down for more than a day at a time, and when a landline connection could take over a hundred days to arrange and come with a heavy bribe attached, opting for mobile telephony made sense. Because of the initial expense of the handsets, mobiles started as office technology in the hands of the rich, educated and employed. Yet by 2009, the lower prices for handsets and cheaper pay-as-you-go ‘airtime’ tariffs allowed 17 million – 47 per cent of the total population – to own their own private phone.

This is in sharp contrast to access to the internet or banking. In 1999 there were less than 50,000 internet users in Kenya, rising at a rate of about 300 a month; by 2011 this had reached just under 9 million, but with only 85,000 of those users having access to broadband. Some 99 per cent of all this internet traffic actually comes from mobile devices, and as a result Safaricom controls 92 per cent of the market.

There is also limited access to banking: in eastern and southern Africa overall, less than 30 per cent of the population has a formal bank account (ranging from 63 per cent in South Africa to only 9 per cent in Tanzania). In Kenya, as elsewhere, access to services is the main problem: in 2006 there were only 860 bank branches throughout the whole nation, and 600 ATMs. The transfer of money, therefore, is rarely conducted through a traditional bank; instead, the post office or Western Union office is used as an official courier at a price; bus drivers or taxis are also often used to carry money from one location to another with the high risk of theft.

As a result of these two problems, one of the key innovations that has occurred in Kenya is the exponential rise of M-banking: using the mobile phone to transfer money. In 2006 the London-based team within Vodafone UK, led by Nick Hughes and Susie Lonie, and sponsored by the Department for International Development, developed M-Pesa (‘M’ – ‘mobile’, ‘pesa’ – Swahili for money), a micro-banking facility employing the mobile network to transfer funds, pay bills and deposit and withdraw money. The operation, which was then adopted by Safaricom, was intended to be simple: there are no costs to signing up or making a deposit. Once you’re signed in, the facility is also easy to use and launches from the phone’s main menu, asking the user for identification and validation before offering a selection of services; for a money transfer, the user is asked to identify the recipient’s phone number and the sum to be sent, and then to confirm the whole transaction.

M-Pesa offers a new access to banking, but also has an impact on the real economy. In comparison to the sparse distribution of banks, Safaricom now offers M-Pesa from over 23,000 authorised outlets, ranging from dedicated booths painted in the distinct green of the network’s logo to supermarkets, phone shops, petrol stations and other banks.

The other thing to note is the sums of money that are being distributed through the network. In 2010 there was a monthly gross transfer of funds of US $320 million, a factor of approximately 10 per cent of Kenya’s GDP as well as $650 million in deposits and withdrawals. That year seventy-five companies also moved their payment systems onto M-Pesa, including the largest electricity utility company, which now services 20 per cent of its 1 million customers through the network.

An advertisement for M-Pesa

Yet the average M-Pesa user has only $2.30 in their account; only 1 per cent of account holders have more than $13 in total. Despite the fact that the network handles a vast number of transactions, they are usually very small. As well as convenience, therefore, the service offers banking to the ‘unbanked’, those who previously have not had access to saving and deposit facilities. In particular, it is noticeable how many are using the system to send money home. M-Pesa provides the connection for money to pass from the city to the family back in the village; it offers security within a turbulent and precarious economy. It guarantees a simple solution for the poor to save and manage their money, promoting financial inclusion which is, for some, the first foothold in the urban economy.

There are now schemes for even the poorest to get connected. In August 2011 the UN announced a new initiative to help the billion worldwide who live on under $1 a day to have access to telecommunications. Under the Movirtu scheme, communities can share a phone; however, each person is to be given a unique number to make and receive individual calls. Therefore a community can come together to purchase a phone yet with a guarantee of privacy for each individual.

It has often been suggested that the latest technology threatens the city. For the bestselling futurologist Alvin Toffler technology allows one to be connected anywhere in the world and thus we will all live and work remotely in ‘electronic cottages’, far from the city limits. Why tolerate the problems of the city when we no longer have to live on top of one another?

But strangely enough, thanks to new technology – mobiles, the internet, Web 2.0 – we are now more and more likely to embrace the complex density of the city than ever before. For whilst technology makes communication easier, it does not stop us desiring the closeness of other people. In addition, as communication becomes cheaper, the value of human contact rises. Technology does not supersede the things that make the city so unique – creativity, community and diversity – but it can increase the complexity and depth of our connections.

In a 2011 study of Twitter users, the figures showed that, despite the global nature of the social network, usage was predominantly urban, and local. Painstakingly calculating the geography of over 500,000 messages, the results show that while social media is extremely good at collating weak ties, it was also used to enhance real-world connections rather than replace them.5 In effect, technology makes us more social, desiring closer real connections, not less.

This may seem counterintuitive but it has a big impact on making our cities more important as places where we come together. The results, however, are not without consequences. Social media can start a revolution, but it can also drive a riot or reinforce the violence of a brutal regime. Bandwidth is not a panacea that will change the world by itself. Three examples from London, Cairo and Nairobi show the different ways social media can transform a city.

On the night of 6 August 2011, when the riots started in Tottenham, north London, #TottenhamRiots started to be passed around on Twitter. The following morning, a ‘ping’ appeared on the BlackBerry messenger service: ‘Start leaving ur yards n linking up with your niggas. Fuck da feds, bring your ballys and your bags trollys, cars vans, hammers the lot!’ It was then forwarded and spread across the network. Secure, only available to users with a BlackBerry handset and a PIN, the message was a call to arms. Over the next three days, the network became the nervous system of the mob, connecting rioters and looters, sharing images and coordinating the rampage.6

Six months before that, on 8 February, protesters filled Tahrir Square and Twitter began to generate another wave of messages linked by the hashtags #jan25; #tahrir; #egypt. Since 14 January, when the Tunisian president Ben Ali stepped down in the face of widespread anger, people had been using social-media technology to discuss and organise protests against the Mubarak regime. Tuesday 25 January was decided as the ‘Day of Revolts’ and in preparation postings were put up on Facebook; Asmaa Mahfouz placed a video on her page calling for everyone to march: ‘I, a girl, am going down to Tahrir Square, and I will stand alone . . .’7 Her challenge spread like a virus.

Elsewhere, Wael Ghonim, head of marketing for Google in Dubai, returned home and started to coordinate protests through the ‘We Are All Khaled Said’ Facebook page, a site he had created in memory of a young Alexandrian who had been beaten to death by the police the previous year. The day after the first protest, the authorities were so taken aback by the size of the march that the internet was switched off; on 27 February Ghonim was arrested and was not seen for the next twelve days until the Mubarak government was eventually closed down. In later interviews, Wael Ghonim personally thanked Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, for his role in bringing down the government.

On the morning of Friday, 11 February, the atmosphere in Tahrir Square was tense; during the night the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces issued a second communiqué, but no one really understood what they had said. After morning prayers, the crowds began to swell. At 5.20 am nearby Ashraf Khalili tweeted: ‘I can still hear the drumming and chants from tahrir from my balcony. “Not afraid. Not afraid”. You gotta love these guys.’8 As the day continued, social media was used to encourage people to stay strong, to coordinate marches to the TV station and the presidential palace; to circulate information and news; rumours churned through the network but were quickly scorched. There was even time for humour, Sultan Al Qasssemi joking: ‘You know you’re in trouble when: Iraq embassy in Cairo urges Iraqis to return home.’9

At 18.02 Amr El Beleidy announced ‘Omar Suleiman speaking now!’ Just twenty seconds later 3arabawy updates ‘Mubarak has stepped down, says Omar Suleiman’. Two seconds later MennaAmr reacted with ‘WHAT THE FUCK!’ and over the next few minutes the message stream was filled with celebrations. ManarMohsen wrote: ‘Who did this? WE did, the people. Without guns. Without violence. Rather, with principles and persistence. Mabrouk, everyone!’10

In Kenya, three years earlier, people were also in the streets. In December 2007, following the contested elections, violence broke out across the country as Mwai Kibaki was named president for a second term. Many of the opposition, as well as official observers, accused the president of corruption and manipulating the polls. Nonetheless he was sworn in three days later in the face of a number of non-violent protests, urging peace in his New Year’s message. The peace did not last long and the following day the BBC recorded that they had seen forty bodies belonging to demonstrators in the Kisumu mortuary; later, images of police shooting unarmed protesters appeared on YouTube, while stories began to circulate that some thirty people had been herded into a chapel and the building then set alight.

By 2 January the death toll had escalated to 300 and was gaining international attention. This only led to more recriminations, failed mediations between the parties and clashes between protesters and police on the streets; by 28 January the toll had risen to 800.

Ory Okollah had returned home to Kenya from Johannesburg to vote but found herself stuck in the family home with a child and a laptop. While she ran out of supplies, she maintained her blog on Kenya politics until she decided she was no longer safe and left for South Africa. There, she posted updates and blogged on the possibilities of using Google Earth satellite imaging as a means to crowd-source stories. Within days, she had responses from other bloggers and engineers including Erik Hersman, David Kobia and Juliana Rotich and within weeks they had created the Ushahidi (Swahili for testament), and were coordinating reports of violence sent in by text or phone and then mapping them on an interactive Google Earth map.

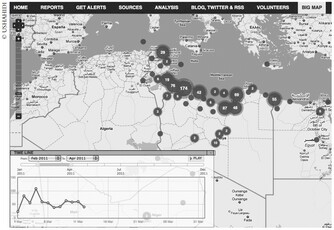

Ushahidi used the same complex network of telecommunications as the rioters in London and the protesters in Cairo to gather together real-time information. Where it was different was that it used mapping and location in order to bring help and also to act as a witness to events. When the UN Commission on Human Rights visited Kenya in February following the resolution of the crisis, they concluded that ‘greater accountability and an end to impunity will be key to addressing the underlying problems and preventing further outbreaks’.11 Ushahidi, despite being a non-governmental group, set up by passionate bloggers, offers a software platform that can be used in any kind of crisis.

Since 2008, the platform has been improved and made freely available for anyone who wishes to download the tools from the Ushahidi website. It has been utilised to collate election data in Liberia, Morocco, Nigeria, Egypt, Tanzania, Brazil, Sudan and the Philippines. In addition, the crowd-map software has been adopted in any number of ways: in Belarus, it is being used on www.crisisby.net to monitor human-rights violations by the regime of the last dictator in Europe. Women Under Siege collects data about atrocities and sexual violence against women in Syria during the uprising.

The applications for crowd-sourcing maps can be almost endless. In Taiwan, Angry Map records reports of bad behaviour in the hope of naming and shaming people into civility. [Im]possible living is a site in Milan, Italy, that discovers abandoned buildings and hopes to connect them with schemes for potential reuse. In New York, crowd-sourcing maps software drives the Future Now NYC programme, which gathers together ideas from local schoolchildren about ways to improve their community, from more trees and a football field to ‘gun free’ teen clubs. The CUNY Grad School of Journalism has also collected data to create a map of danger spots in the Brooklyn neighbourhood of Fort Greene, adding both traffic accidents and street thefts to show how users can avoid them.

A website using Ushahidi software showing reports of human rights violations in Libya during the uprising in 2011

One of the most extraordinary uses of the Ushahidi platform is at moments of natural disaster when infrastructure is often at its most fragile and real-time information from people on the ground, NGOs and emergency services really does mean the difference between life and death. On 12 January 2010, Port au Prince, the capital of Haiti, was hit by a devastating earthquake. Within hours the city was reduced to rubble: hospitals collapsed, infrastructure was torn out at the roots, radios went silent as there was no electricity or broadcasts, while the streets were so strewn with debris that it was difficult to travel anywhere.

There was no way anyone could calculate the level of the damage, the number of people lost or dead, the families torn apart. Within twelve hours a dedicated Ushahidi website had been launched, first reporting on problems at the airport. This was followed by notices of a building collapsed at Delmas 19, Rue Mackendal, and the destruction of the national palace; the next morning, it was announced that a hospital to the north-west of the city was still in operation, fully staffed, while there were calls for food in the Bel Air neighbourhood. Soon there were requests to find lost people, friends, family, a doctor. All the messages were catalogued and then placed on the map to give location, time and specific need.

At the same time, techies, cartography fans and NGOs were looking at other means to help on the ground. Even before the quake, Port au Prince had been a chaotic city; beyond the central neighbourhoods there had been few attempts to map the slums, shanties and informal streets. Many of these were out of bounds to officials; others were in such a state of flux that no map could reasonably keep up to date. However, in this time of desperation, there was a need for accurate maps so that aid could be delivered where necessary. Using Openstreetmap, volunteers pored over Google Earth satellite maps tracing primary and secondary streets, damaged buildings and, as they emerged, refugee camps.12 Within forty-eight hours, volunteers working independently around the world were changing the way aid workers were operating on the ground, giving them accurate locations and data.

Sitting beside my son on the sofa, we often set off around the world. Our journey usually starts at home: we find our street and then our house and imagine that the satellite is picturing us at that very moment. We then decide where to go: this time – the Pyramids. The image zooms outwards; our street becomes part of the cross-hatched urban fabric; then the city fills the screen, then the outline of Great Britain dusted with clouds and encircled by sea. The camera seems to halt, momentarily standing still in space, then begins to swerve right, and down, south-eastwards, across Europe, over mountains, along the length of Italy, skimming the Mediterranean until the screen becomes dusty brown and burnt red as we reach north Africa. Finally, the focus begins to zoom inwards even as we continue to travel: Cairo, indicated by a small yellow star, begins to expand and grow into a city. We are destined for the edge of the metropolis, a place where the desert meets the suburbs: Giza.

And there they are. Initially, the Pyramid of Khafre is almost impossible to see, the stone the same russet colour as the surrounding landscape; only the shadow of the east face makes it clear that this is a vast structure. My son clicks to get a better look and then uses his finger to move around the site. He tells me all that he has learnt in his recent lessons on Ancient Egypt. He finds the Sphinx, close by the Valley Temple of Khafre, and is almost speechless with excitement. He tells me the whole story of the riddle of the Sphinx and how Oedipus was able to outwit the mythic monster. He then wanders through the Eastern Cemetery and goes in search of the Tombs of the Queens.

Later, I return to Google Earth and move from Giza and the historic site of the Pyramids, to go in search of Tahrir Square; and because it does not appear in the search facility, I try to work out from the city plan where it might be. Cairo is so vast and chaotic, even from the air, that it is difficult to tell where the city centre might be. The map is studded with miniature tags that link to Wikipedia, and so I can find information on Boulaq, the Coptic Museum, the 6th October Bridge built in memory of the Yom Kippur War of 1993; I can also find where the metro stations are. From the east side of the bridge I find the Egyptian Museum and then the square. There is little evidence of the crowds from February 2011.

I also look at other cities that have been in the news recently: the Fukushima nuclear plant that was damaged by the earthquake in March 2011; or I peer over Kabira, the slums outside Nairobi, where the shacks are so closely packed together that it is impossible to see where the streets and alleys wind through the neighbourhoods; finally, I click to the High Line in New York, and watch in wonder at how a channel of verdant green snakes through the city.

Google Earth brings joy and fascination, but it can also be used to make a difference. In 2008 Clean Up The World started to use it to highlight places of particular crisis as well as show the impact of the International Clean Up Weekend. It is also being used to track the loss of the Antarctica ice cap, the depletion of the rainforest in Amazonia, measuring the largest oil spills in the world’s oceans13 as well as the extent of urban sprawl in cities like Houston and Phoenix.

Google Earth is already having an unexpected impact on urbanism. In Dubai, islands are being designed to be seen from the air. Palm Jumeirah is a man-made island that spans out into the Gulf in the shape of a palm leaf that can be seen by satellite or aeroplane. Elsewhere the availability of aerial images has changed the way a city is run. In Athens, in the aftermath of the Euro crisis, the Greek government has been using Google Earth to find out who has a swimming pool in their gardens and then checking this apparent wealth with their tax returns. This has resulted in a number of gardens being covered over in the city. During the Olympics, ‘Adizones’, ‘giant multisport outdoor zones’ sponsored by Adidas and offering a selection of gym equipment as well as dance and gymnastics, were built in public parks around London. From the air these projects clearly marked out the shape of the 2012 Games logo.14

The Palm Jumeirah, Dubai – the city designed to be seen from Google Earth

Finally, in my laptop tour of the world, I type in the name of a city that does not even exist yet – Songdo – and am taken to a patch of bare ground to the west of Seoul, South Korea. This new city is to be built on land that has been reclaimed from the Yellow Sea, and is planned to be the most advanced technological city in the world. Songdo has been designed with the network in mind, working alongside the Silicon Valley software giant Cisco’s Smart+Connected systems, which converge technology, architecture, people and urban life into seamless unity.

This is a new generation of metropolis: the smart city, built according to the new rules of the Information Age. It is a connected city in which real-time information monitors and regulates the urban fabric; buildings, objects, traffic lights are both sensors and activators. The new city is no longer a static collection of places but ‘a computer in open air’. It is a sentient place, which can gather information, change, and react to the feedback; in the words of Assaf Biderman, associate director of the SENSEable City Lab at MIT, smart technologies can make ‘cities more human’.15

But how can technology possibly make our cities more ‘human’? One is right be to suspicious of such techno-utopianism; wasn’t Le Corbusier’s dream of the autopia a similar fantasy? What can machines do that people can’t?

The first noticeable change in the smart city is that everything is connected. The first mobile-phone network, NTT, was set up in Japan in 1977; since then handsets and networks have spread across the world. By 2002 there were 1 billion connections, rising to 5 billion within eight years. With a total world population of over 7 billion, even with some people having two mobile phones, this seems an unexpectedly high number. Clearly the figure includes more than the connections between people with mobile phones, ringing and texting each other. In the last few years, there has been a proliferation of machines connecting to each other rather than human connections: the dial-up desktop computer, superseded by broadband, and now by wireless bandwidth, 3 and 4G, tablet technology, and other mobile computing devices. At the same time cloud computing widens the connexity of things, making it easier to access our data from any place.

However, it is not just our phones and computers that are now connected, we will soon live in the ‘Internet of Things’ where the internet enters the real world and collects data from every object around us, so that every aspect of our lives interacts. Data will be collected every time we use the public-transport system, our cars can be connected to the garage to tell them when there has been a fault, traffic lights and road signs will contain sensors that detect congestion and traffic flow, smart buildings will regulate internal temperature or lighting, face-recognition software might be used for everything from banking to security.

The city is becoming not just a collection of places and bodies but a living and connected network in which buildings, signs, users and vehicles communicate with each other in real time. This may sound like science fiction but there is no HAL 2000-style mainframe taking control over the city, nor is this Metropolis, Fritz Lang’s dystopian image of the late-industrial world. The smart city uses technology as a tool to collect vast amounts of information which we can then employ to improve the way things work around us. It is a means of informing the real world, not replacing it, creating what Anthony Townsend of the California-based Institute of the Future calls a ‘blended urban reality’.16

Songdo is a new city being built from the top down. In the 1990s Korea had been hit hard by the global recession and was forced to accept IMF backing, which included as one of its stipulations that the local market had to be opened up to international trade and foreign investment. Initially, there was little interest and as a result the government developed a series of free enterprise zones, FEZs, to tempt new sectors like logistics, financial services and IT. This coincided with a reclamation project on the land near Incheon International Airport which included three small islands, one named Songdo, the Isle of Pines. Most of this work had been contracted by Daewoo, which hoped to create a ‘media city’ to compare with Silicon Valley, but when the corporation got into financial trouble, Songdo was abandoned and the city authorities contacted the Korean-born American businessman Jay Kim, who had previous experience of working on big projects as well as having strong US contacts. From his office in Pasadena, California, Kim started to make enquiries amongst the major American developers.

Over the next few years a team was put together, including John B. Hynes III of Boston-based Gale & Wentworth, and Stan Gale, who quickly started to negotiate with the city office, as well as the Korean steel giants POSCO, and leading urban architects Kohn Pedersen Fox, who developed a plan for what was now being called Songdo International Business District (IBD). By 2002 the masterplan had been formed to include a community of 100,000 residents and workspace for another 300,000. The city was to be broken down into zones: 50 million square feet of office space; 30 million square feet for residential; 10 million square feet for retail; 5 million square feet for hotels.

There was also to be a convention centre, a golf course designed by Jack Nicklaus, a mall, an iconic skyscraper, schools, a central park and water features. It would all be built to the highest sustainability standards and be linked to the international airport by a bridge that ran 7.6 miles across the Yellow Sea to Incheon. As one marketing brochure points out, Songdo takes the best of the world and makes it even better:

Canals were modelled after Venice’s Grand Canal; its skyline after Hong Kong; the cultural centres after Sydney’s Opera House; and the pocket parks in residential areas mimic Savannah, Georgia. Songdo IBD’s Park Avenue and Central Park will create a mix of relaxation and urban sophistication like their namesakes in New York. Finally, the government center’s location at the axis of a hub of spokes draws upon Paris’s Arc de Triomphe.17

Yet it is the technology at the heart of the city that makes it more than the Las Vegas of Asia. By January 2012 it was already home to 22,000 residents, a number expected to rise to 65,000 on completion, in addition to a commuting population of 300,000 who will arrive by transit or from the nearby airport in Incheon for business. The skyscrapers, public spaces and gardens, impressive plazas and feats of engineering herald a bold and confident metropolis, the compliance of the whole city to the highest Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards make it one of the most sustainable environments imaginable, but it is the invisible connections, the city as Internet of Things, that is truly impressive. Songdo is more than the people or the buildings within it, and even more than the infrastructure of roads, water, waste, transit and energy; it is U.Life. As Tom Murcott, executive president of Gale International noted: ‘The enabling technologies need to be baked into the masterplan and initial design and development from the get-go, rather than a follow.’18

U.Life puts new technology at the centre of the city, and since 2008 Gale has been working with Cisco to deliver the intelligence to run the smart metropolis. The whole city will operate from a hub that functions as Songdo’s ‘brain stem’.19 Here, for example, cameras will report on the flow of pedestrians on the street, and brighten or dim the pavement lamps accordingly; ‘radio frequency identification tags’ will be attached to car number plates to watch traffic and reaction to congestion; monitors on buildings and roads will report on conditions to avoid costly works or unnecessary delays; there will be real-time weather forecasts that can prepare the power grid for surges in demand when it gets suddenly cold; at other times, the smart energy grid will monitor usage and flows and predict demand as well as search for efficiencies; there will also be a smart grid for water and waste.

Each home will also become smarter: there will be touchpads in each apartment so that one can control temperature and lighting and track energy use. Smart architecture will help the sustainable city – there will be roof gardens planted with vegetation to reduce the ‘heat island’ effect, and reduce storm-water run-off. There will be no waste collection as everything will be processed by a centralised system that sucks all the rubbish away.

This appears to promise the best of all possible places, inspired by the finest examples of architecture from around the world, smarter than any previous city in order to make the mundane moments of urban living run smoothly: improving traffic congestion; energy efficiency and smart buildings; enhanced security and surveillance. The instant city, super-smart, built from the ground up from a masterplan is, for many, the vision of the future, the latest version of a hi-tech Utopia, and it can be found across Asia.

Songdo is not alone in attempting to find a new urban order, and many of the latest cities sound more like aisles in an electronic store than metropolitan areas: Putrajaya and Cyberjaya form part of the Multimedia Super Corridor in Malaysia, built in the last decade out of land previously covered by rubber plantations. Mentougou Eco Valley has been designed west of Beijing by the Finnish architect Eriksson as a beacon of what a city could be. Elsewhere in southern China there are plans for the self-styled Sino-Singapore Guangzhou Knowledge City. Outside Abu Dhabi, an ambitious new city, Masdar, is being designed by Foster + Partners, which promises to be the smartest zero-carbon city on the planet.

But this vision of the smart city raises many questions and concerns. What happens when the whole city runs on one type of software and you want to use another – will you be thrown off the grid? What if you want to develop your own code, adapting some of the city’s software – will you end up in court for hacking? Who owns the city when it runs on someone else’s software? Can it continue to develop and change when the digital infrastructure is copyrighted? What if, as Anthony Townsend warns, ‘one company comes out on top, cities could see infrastructure end up in the control of a monopoly whose interests are not aligned with the city or its residents.’20

There is lots of money to be made from talking about the smart city. From theorists prophesying their visions, architects with their design innovations, management consultants who wish to sell their solutions, software companies who have developed the proprietary code to run the new world, making and marketing the smart city is big business. Big players such as IBM, Cisco, Siemans, Accenture, McKinsey and BoozAllen are all entering the debate on the intelligent city, the smart-grid, next-generation buildings, developing the tools to bring efficiency, sustainability and a connected metropolis. These big companies are talking to city halls, offering end-to-end solutions, the complete package to retrofit the everyday city for the twenty-first century with a very hard sell.

How Smart Is Your City, produced by the IBM Institute of Business Value, supplies tools for assessing the connectedness of any city and offers a road map:

Develop your city’s long-term strategy and short-term goals

Prioritise and invest in a few select systems that will have the greatest impact

Integrate across systems to improve citizen experiences and efficiencies

Optimise your services and operations

Discover new opportunities for growth and optimisation.21

In a corresponding document from the same team, A Vision of Smarter Cities, the researchers go into more detail on how ‘smartness’ can be achieved. What is clear from this big-business perspective is that change must come from the top down: ‘city administrators should develop an integrated city-planning framework’.22

IBM’s command to ‘think revolution, not evolution’23 needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. Despite the maverick rhetoric, we need to be cautious of these digital Baron Haussmanns of the future. Can there be a more bottom-up solution that offers some form of ‘open-source’ city, where information and knowledge is freely distributed rather than proprietorial, and is developed by those who use it rather than those looking for something to sell? This kind of ‘open-source’ city can adapt and transform as times and demands change; it responds to and reflects the street as much as it does city hall or the marketplace.

Perhaps it is the bottom-up development of technology that is best suited for retrofitting existing cities. Without pulling the whole edifice down and starting again, the cities we live in today need to embrace the latest ways to make them more efficient and sustainable. Technology can be used for inclusion with great impact: M-Pesa offers banking services for the first time to millions who never had an account in Kenya; it is also very good at collecting and gathering data. The smart city is one that integrates the big city-hall projects but allows more open-source involvement to continue. If not, there is every chance that it will be proven once again that we learn nothing from history and the two sides of the digital divide – the cyber Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs – will clash, just as they did in 1961.

The bottom-up ‘info-structure’ will not by its nature be an ‘end-to-end solution’. It will combine a number of devices and platforms, from electronic road signage, mobile phones and GPS, to bikes and maps. It will undoubtedly exhibit some of the most creative and innovative thinking about the metropolis, opening up new ways of navigating our cities, making urban life easier and more diverse. It will integrate the old and the new, weaving together the physical city with the digital grid, offering information as well as the tools for change.

The SENSEable City Lab at MIT, outside Boston, is one of the leading research centres into this potential future of the smart city. In 2009 the director of the lab, the architect and civil engineer Carlo Ratti, proposed that the 2012 London Olympics should be celebrated with the creation of a cloud, a transparent observation deck high above the stadia of Stratford. The floating world would be accessed by a circling ramp that rose from the ground into the air, spiralling for 1 kilometre. The structure was alive ‘with an LED information system which densifies locally into lightweight info-screen hotspots where visitors can navigate information about the immediate surroundings’;24 in effect transforming ordinary citizens into true Olympians, and turning the traditional Olympic monument on its head. It was clearly a dream unlikely to see the light of day; but it is this kind of rethinking the relationship between the city and place that excites Carlo Ratti and informs the work at the SENSEable City Lab.

Cities are vast networks of information, but thus far gathering the data at the levels that make a difference has been very difficult; this is now changing. The smart city is a sensor. Ratti’s team at MIT have looked at a number of projects that help the gathering together of huge sources of information that allow us to understand the city – not how we think it might work but how it actually, empirically, functions. The Lab has invented a number of exciting devices that help this gathering of data.

‘Trash/Track’ are small sensors that the Lab tested to uncover the waste chain, what really happens to our garbage. In an experiment conducted in 2009 in New York, Seattle and London, 3,000 electronic tags were attached to different types of rubbish, and their movements were then mapped, revealing just how far our waste travels, questioning the sustainability of our recycling policies.

The Copenhagen Wheel is one of Ratti’s most ingenious data sensors. Encased in a red plastic disk, it sits on the back wheel of a bicycle and was first used in the Danish capital in 2009. The device is a miniature engine that stores up energy from the bike when it is moving for those moments when you need a little extra push. The shiny red disc also hides sophisticated sensors that help the rider in a number of scenarios: connected to the iPhone via an app, the wheel collects the data for your fitness regime: distance, time, calories. It can also help navigating the city and monitoring levels of congestion and pollution. Thus it can tell you in advance whether there is traffic ahead, the condition of the roads, the best diversion. This information can also then be shared with friends or others in the neighbourhood.

The SENSEable City Lab is also looking at experiments on a city-wide scale. LIVE Singapore is an on-going project to connect all the data from various government departments to offer a real-time data feed of everything that is going on in the city. While developing an open digital platform that can absorb data coming in from every point in the city as well as an interface that can be accessed by everyone from politicians, traffic police and ordinary citizens on multiple devices, the project has already been collecting data on how Singapore works. It now includes an isochronic map, showing the time it takes to move about the city at various times of the day and where the problems occur. There is also a way of improving the distribution of taxis around the city, how big events like the Singapore Formula 1 Grand Prix disrupts the infrastructure, what the measurement of mobile-phone usage reveals about the way people go about their lives.

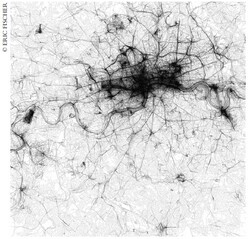

As the LIVE Singapore research shows, valuable data can be found in the most unusual places. Eric Fischer is a self-confessed map geek from the Bay Area and loves to rebuild maps of the city through unexpected data sets to show more than just the geographical or the street plan, but the topography of human activity. For example, in his series of Geotagger’s maps he set integrated maps of the great cities of the world with tagging information from the vast photo-sharing website Flickr. Thus the map of London became a graph of the most photographed places. Fischer was then able to break down the data to show how differently tourists and locals use the city. This type of info-mapping changes the way we look and understand the city, not just as geography but as a living, transforming human landscape.

This real-time data can empower the city. The smart city offers the kind of data that helps us make better decisions about our urban lives; it can also create feedback loops that make the running of the city more efficient. Driving too fast down a city street, often a sign with the number 20 surrounded by a red ring is not enough to make one put on the brakes. Does your behaviour change when a digital sign flashes your speed on a board? This is a very simple example of how feedback loops of real-time information can influence behaviour; what happens if we can integrate feedback loops into every part of the city?

Eric Fischer’s geotagged map of Flickr images of London

Like the Copenhagen bikes, a number of researchers have done similar studies with taxi drivers in Beijing, such as the T-Drive initiative shared between the University of Science and Technology and Microsoft. Today in the capital of China the rapidly expanding population of nearly 20 million makes for congested, polluted roads; amongst the traffic of cars, trucks and carts are 90,000 taxi drivers who have a reputation for being surly and uncommunicative, and often new to the city. For them, the meter continues to run whether they are at a standstill or buzzing down the highway. However, a group of researchers decided to work with 33,000 drivers and, using a combination of dashboard-mounted GPS monitors and cloud-computing technology, were able to create an intelligent, real-time traffic service.

Studying congestion on all 106,579 roads within the city, a distance of over 5,500 kilometres, they created a smart grid forming a digital map of the city. This was also integrated with weather and public-transit information. As a result, in testing, the new smart grid improved 60–70 per cent of all taxi trips and made them significantly faster.

The smart city is being built from a combination of big city-hall projects alongside major software companies as well as more humble schemes that can be found on the 3 or 4G mobile in your pocket or the sat nav on the dashboard. Yet the city of the future, however connected it may be, is only ever going to be as smart as the people who use it. Information is not an end in itself, it is a means to come up with better solutions to the problems of urban life. Yet it is surprising how thinking about the smart city forces us to reconsider other aspects of the city. Does technology help us face the problems of congestion? Can smart building make the city of the future more sustainable?