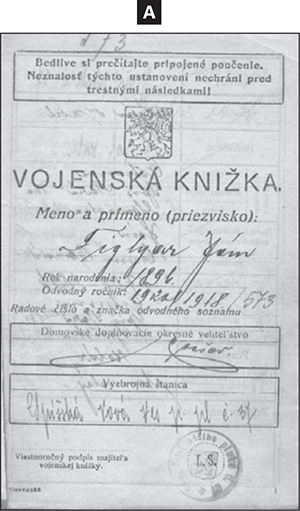

Jan Figlyar’s military book (Vojenska Knizka) provides valuable information about him such as year of birth.

Military records are often considered a secondary resource for genealogical researchers exploring roots in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia. Why? Because they are not easy records to locate. If you can locate these records, however, you could enhance your understanding of both the time period during which he lived as well as insight into his personal and family life.

To find military records for the Austro-Hungarian Army, you first need to determine where and how to look for them, since they were kept at different locations throughout history and were kept differently for the various states within the empire. (Review chapters 4 and 5 to understand the history of the Austrian Empire and the subsequent Austro-Hungarian Empire.) Also consider that the army not only protected the country against external threats, but also maintained control of the various ethnic groups within its borders. There is a useful timeline of historical maps to aid you in further understanding the history of Hungary at <www.zum.de/whkmla/histatlas/eceurope/haxhungary.html>.

There are a few other general principles to keep in mind when searching for military records. The time period in which your ancestors lived is perhaps the most important, as this determines whether your ancestor served during the Partitions of Poland or the Austro-Hungarian rule over the Czech and Slovak republics (see the timeline of War in Eastern Europe). Next, you will need to know how the process of conscription worked and the regiment/military unit your ancestor served in, though finding this information is not always an easy task. Finally, you will need to become familiar with the types of records (e.g., muster sheets, personnel sheets, military citations), which vary by regiment and period. The following is a brief summary of what to expect with military research in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, and some of the key military records you might be able to locate for your ancestors.

The modern Poland, Czech Republic, and Slovakia have been at the crossroads of various conflicts for centuries, and understanding when some of these conflicts occurred can be crucial to identifying and finding military records that your ancestors can be found in. Check out this timeline of major military conflicts that your ancestors may have fought since 1700:

| 1701–1714 | War of the Spanish Succession: Powers collide over the future of the Spanish Empire following the death of King Charles II. |

| 1718–1720 | War of the Quadruple Alliance: Great Britain, France, the Holy Roman Empire (including Austria), and the Dutch Republic curb Spain’s expansionist plans. |

| 1733–1738 | War of the Polish Succession: Hapsburgs and Bourbons struggle over who will rule as the next Polish king. |

| 1740–1748 | War of the Austrian Succession: European states protest the succession of Maria Theresa as empress of the Hapsburg Empire. |

| 1756–1763 | Seven Years’ War: Disputes between France and Great Britain in the New World spill over into Europe, where the major powers collide. |

| 1803–1815 | Napoleonic Wars: European powers unite to defeat France under Napoleon III. |

| 1863–1864 | January Uprising: Poles rebel against the Imperial Russian Army. |

| 1914–1919 | World War I: Allied Powers square off against the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire). Nations (including Poland and Czechoslovakia) battle for independence and over territory from the dissolved Austria-Hungarian Empire. |

| 1917–1922 | Russian Civil War: Revolutionaries overthrow the czarist government and, later, the Communist party takes control. |

| 1939–1945 | World War II: Allied Powers fight to defeat fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. |

| 1968 | Warsaw Pact Invasion: The Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact states invade Czechoslovakia to quash the Prague Spring. |

Poland’s tumultuous history is reflected in the availability of its military records. In his book Going Home: A Guide to Polish-American Family History Research (Language and Lineage Press, 2008), Jonathan D. Shea writes that military records from Poland (if they exist) are most likely to be draft lists, while actual service records will more likely be held by the countries ruling Poland at the time. Shea explains that the latter kinds of records (if extant) will be in Russian or Austrian archives, and that most Prussian military records were destroyed during Allied bombing raids in World War II. To find strictly “Polish” military materials, you will need to look in the Central Military Archives (Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe) in Warsaw <www.wp.mil.pl>. These holdings generally cover Poland’s history from its independence after World War I to the present. You can find details of the archive’s holdings in Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe: 1918–1998; tradycje, historia, współczesność służby archiwalnej Wojska Polskiego by Wanda Krystyna Roman (Marszałek, 1999). A search on WorldCat <www.worldcat.org> will help you find a copy in a library nearest to you. Fragments of pre-induction records containing personal information can sometimes be found in various regional archives. You can search the archives on SEZAM <baza.archiwa.gov.pl/sezam/sezam.php?l=en> (or printed guides) to find the proper record group.

Before you do this, however, you should gain an understanding of the draft system. The partitioning powers began mandatory conscription at different times: Russia in 1874, Prussia in 1816, and Austria in 1868. You can learn more about the draft system in “Russian Military Records from the Kingdom of Poland as a Source for Genealogical Research” by Michal Kopczynski from the University of Warsaw. Contact the Polish Genealogical Society of Connecticut and the Northeast about obtaining a copy <www.pgsctne.org/Publications/Publication Spring 2000 to Fall 2002.aspx>.

According to Shea, it is sometimes also possible to locate draft records from the period of the Second Republic (independent Poland 1918–1939) in the state’s archive system. These registers are in the record groups of the starosta (chief administrative officer). The records deal with individuals over age twenty-one and contain data about the recruit, such as the names of his parents and his place of residence, occupation, level of education, marital status, and condition of health. While only men were drafted, you may find the name of the draftee’s female relatives (e.g., his wife) in these records. Note that in some cases, nobility, government officials, and clergymen were exempt. Use the SEZAM database on the Polish state archives website to learn more. If your family’s origins lie in Galicia, you will also need to examine the military records generated by the Austro-Hungarian Empire (see section below). Learn more at <www.polishroots.com/Resources/austrian_recruit/tabid/204/Default.aspx> or on the FamilySearch Wiki entry on Polish military records <www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Poland_Military_Records>.

Hitler’s campaign to destroy the Polish nation and Soviet atrocities during World War II generated large bodies of records containing personal data of individuals murdered, imprisoned, or deported. These included

In addition, Polish army and air force units joined the British in fighting the Nazis during World War II. Check with the UK national archives <www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-air-force-personnel> for documents from this era if you believe your ancestor may have fought with them. Additionally, after the war, Polish army veterans served with the US Army in Europe, so look for documentation in the appropriate archives. There might be monuments or records in town archives or churches. Also try to connect with historians who specialize in a battle, country, or unit, and check for area war cemeteries.

Don’t forget about the index to Haller’s Army records, available through the Polish Genealogical Society of America <www.pgsa.org>. Named after its commanding general, this Polish army in France comprised nearly twenty thousand Polish immigrants to America that were fighting for Poland’s independence during World War I.

Because the modern Czech and Slovak Republics were once under foreign control (see chapter 5), you’ll have to review Eastern European history to know which country’s armed forces your ancestor might have served in.

After 1802, the term of military service in the Austrian army was reduced to ten years, but many were still exempt from having to serve. In 1868, a universal conscription went into effect, and every male citizen was obligated to serve three years of active military duty.

Military records of Czechs and Slovaks fall under Austria-Hungary until after World War I. In Austria-Hungary, conscription requirements varied over time and national need. In the 1890s, for example, men entered the army at age twenty and were released at age twenty-three with a subsequent nine years in reserves. For later time periods, refer to the resources in the Toolkit: Resources for Military Records sidebar.

In order to successfully research military records for a Czech or Slovak ancestor, you should also understand the administrative and political structure of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Before 1867, the records of soldiers from across the empire (including Galicia, the modern Czech regions, and Hungary/modern Slovakia) resided in the Vienna War Archives. Once the empire formally became a dual Austro-Hungarian government, records were administered and maintained by either the Austrian (Galicia, Czech lands) or the Hungarian (Slovakia) government. The Empire’s successor states (Poland, Czechoslovakia, and other Eastern European countries including Romania, Yugoslavia, and Ukraine) then assumed record-keeping duties following Austria-Hungary’s defeat and disbandment in World War I. Learn more in Carl Kotlarchik’s “A Guide for Locating Austro-Hungarian Military Records” <www.ahmilitary.blogspot.com>. You also can learn more about the army at <www.austro-hungarian-army.co.uk>.

Despite foreign rule for hundreds of years, some records are available in the modern Czech Republic and Slovakia. In the Czech Republic, muster rolls and qualification lists are available from the 1700s through 1915. Military records also have been microfilmed by the FamilySearch. The films are mostly of Austrian records, but some Hungarian records (which, again, include modern Slovakia) are available. These include alphabetically arranged lists of officers and some common soldiers who were not ethnically German. These records are only of value if you know the regiment your ancestor belonged to. Consult Das Österreichische Heer for more information <www.kuk-wehrmacht.de/regiment>.

The search for an ancestor’s military records in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire can be a daunting task. Here is a list of eight essential resources to consult before you begin:

Once you have determined your ancestor’s regiment, you can look for his Grundbuchblätter personnel records, which contain valuable information. From these records, you can learn the soldier’s birth year and location, marital status, civilian occupation, religion, dates of service, description of duties, promotions (if any), and date of discharge.

Military records for soldiers coming from the Czech regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia from 1820 to 1864 are located at the Kriegsarchiv (Austrian State Archives) in Vienna <www.oesta.gv.at>. Each is arranged alphabetically by surname and given name.

Keep in mind that finding copies of later resources can be complicated, if not impossible. According to the director of the Kriegsarchiv, Grundbuchblätter records of soldiers born from 1865 to 1900 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire were scattered among its successor states following World War I. As a result, the Kriegsarchiv only holds records for soldiers born between 1865 and 1900 who lived within the post-WWI Austrian Republic, while records from other parts of the Empire were kept separately. Many of them have been destroyed, though some records of Czech soldiers born between 1887 and 1900 survive in the Czech Historical Military Archives in Prague.

Unfortunately, records for the remaining regions of the Empire are not organized alphabetically by name. To find these records, you must first determine the regimental number using charts showing where infantry regiments recruited in the various regions of the Empire over different time periods. Sources for these charts include

Other records of interest may include the pre-1820 Musterlisten und Standestabellen (Muster Rolls and Formation Tables), records for officers, and information for other types of units within the army beyond those of the infantry, including the Jägers (riflemen), the artillery, the engineers, and the cavalry. Additional types of Czech military records are well described at Czech Census Searchers <www.czechfamilytree.com/military.htm>. For locating the records of individuals who were born before Czechoslovakia became a state but served in the Czechoslovak army, see information from Slovak genealogy professional researcher Peter Nagy at <www.iabsi.com/gen/public/military_records_in_upper_hungar.htm>.

Refer back to <www.ahmilitary.blogspot.com> to learn more about the discrepancies among these different charting resources and for detailed descriptions and sample images of many different types of Austrian and Hungarian military documents. In addition, see the Toolkit: Resources for Military Records sidebar for additional resources.

The FHL has individual soldiers’ records for both Austrian and Hungarian armies until 1870, including military church books for both armies until 1920 and a listing of WWI casualties. WWI records of individual soldiers are only available from the Kriegsarchiv in Vienna.

Records of soldiers who served 1870 to 1914 are more likely to be found in military archives in Prague or Bratislava if the records survived World War II. When the FamilySearch Catalog shows nothing later than 1870, ask the Vienna War Archives if anything is available. The reply will suggest an appropriate national archive when it cannot help.

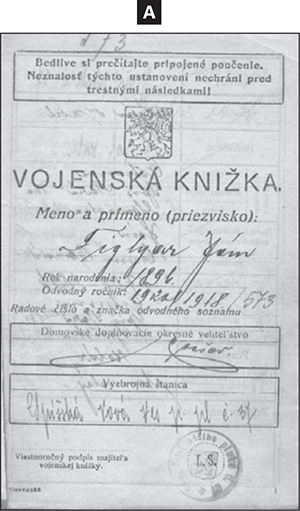

In addition, Bill Tarkulich gives a great overview entitled “Military Records in Upper Hungary (Slovakia)” on his website <www.iabsi.com/gen/public/military_records_in_upper_hungar.htm> that includes images of military documents issued at different time periods including sample muster lists, kmenový (personnel) lists, military citations, and military passports (images A and B).

Jan Figlyar’s military book (Vojenska Knizka) provides valuable information about him such as year of birth.

As this translation depicts, military passports display their subjects’ names, years of birth, and durations of military service.

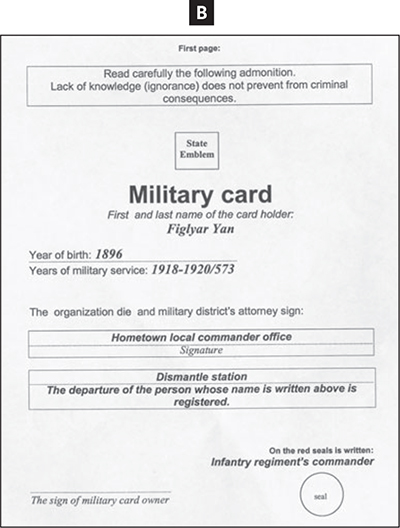

Be sure to scour home and family sources, too. Ask your relatives if they have any similar papers that an immigrant ancestor may have brought with him proving service in the Austro-Hungarian military. For example, I have a book from my grandfather (image C).

This cropped page shows the 1873 entry (second row) for Mihály Fencsák, from Póssa, Slovakia. Details include parents’ first names, height and chest size, religion, and “weak returned” as the decision of the committee for induction or transfer.

There are more than twenty-six hundred titles for Austrian military records in the FamilySearch Catalog. About half of them are personnel and regimental records, and the other half are military church books. These records are accessible on film and online <www.familysearch.org/search/catalog> or via a private search in the archives. All of the records are in German and use German place-names when available (for example, Slowakai for Slovakia). Cities, towns, and villages also may have German place names (refer to gazetteers). Search the FamilySearch Catalog under Austria—Military Records or Hungary—Military Records. If you don’t find the records from Prague in the catalog, you can hire a private researcher to do a search for you.