“The settlement of the North American continent is just as little the consequence of any claim of right in any democratic or international sense; it was the consequence of a consciousness of right, which was rooted solely in the conviction of the superiority and therefore the right of the white race.”

ADOLF HITLER, Speech to the Industrie-Klub of Düsseldorf (January 27, 1932)

How many Indians were in North and South America before contact?

The shortest and most honest answer to this question is that nobody knows for sure. Genomic and archaeological research is starting to give us more accurate information about how many groupings of people there were and the size of the communities and cities in which they lived. But a deep understanding of the true size of the indigenous population of the Americas at the time of Christopher Columbus is complicated.

Europeans brought diseases to which Indians had little natural immunity, and those diseases, traveling far faster than Europeans, rapidly depleted the native population. By the time Europeans were trying to explore the continental United States, the diseases they had brought to the coast had already ravaged the local settlements. Bartolomé de las Casas estimated that the indigenous population of Española, now known as Hispaniola, island of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, was two million people. Other Spanish chroniclers during Columbus’s first four trips affirm that estimate—all for just one island in the Caribbean. The Spanish also estimated that the indigenous population within the Aztec Empire was more than ten million people. Archaeological evidence confirms that the capital city of the Aztec Empire was three times larger than the largest city in all of Western Europe at the time. Las Casas believed that the Spanish Empire killed between forty and fifty million people in Mesoamerica alone.

The East and West coasts of North and South America were very densely populated, more so than Western Europe. People in desert regions and the Great Plains spread out and competed more intensely for control of land and resources. Conservative estimates of the indigenous population of the Americas range from twenty to fifty million people. Others put the figure between seventy and ninety million or even more. Plenty of conflicting research and writing on the subject exist. A good way to get a handle on the various lines of thinking, to understand the work of prominent scholars, and to arrive at a reasonable conclusion is to read Charles Mann’s book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus.

I find the higher estimates more convincing, but archaeologists have only scratched at about 1 percent of the earth’s surface. Europeans chose many of the same sites as did Indians for their major settlements (Green Bay, St. Paul, Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, Mexico City), making archaeological research in these places more difficult. But archaeological research and new technologies continue to develop, and we will have more and better answers to this question in years to come.

When did Indians really get to North America?

Between 45,000 and 11,000 years ago, the buildup of continental ice sheets lowered sea levels and exposed a shelf of land between Alaska and Siberia.1 Most archaeologists used to believe this was the primary route people took to enter the Americas, and some still do. But the dates and means by which the Americas were populated is a subject of much contemporary scientific debate.

Many American history books assert that Indians became the first Native Americans when they arrived in this hemisphere nine to ten thousand years ago by crossing this land bridge and moving down an “ice-free corridor” into the modern-day United States. Those books point to an archaeological site in Clovis, New Mexico, containing human-made tools used to kill large mammals as the oldest indisputable evidence of humans in the hemisphere.

This theory of human origin in the Americas (usually called the Clovis First Theory) is now widely challenged in the scientific community. Recent research on the Clovis site by Michael Waters, Thomas Stafford, and others has confirmed human evidence there between 10,900 and 11,050 years ago. At Monte Verde in Chile, Mario Pino and Thomas Dillehay found human tool marks on mastodon bones and evidence of human-made structures dating back 13,800 to 14,800 years. At the Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, James M. Adovasio and other archaeologists have found tools, ceramics, lamellar blades, and lanceolate projectiles that are radiocarbon-dated 16,000 to 19,000 years old.

At least fifty other major archaeological sites also suggest evidence of human existence in the Americas anywhere from 19,000 to 50,000 years ago. Some sites show evidence of human beings in the Americas before the last land bridge connected the continents. Archaeologists are still arguing about the dates and the validity of many sites, but increasingly the scientific community is saying that the Clovis First model of human migration to the Americas is simply wrong. Most scientists now favor the theory that people came to the Americas either by land or by traveling along the Pacific Coast in boats long before the Clovis dates.

Why does it matter when Indians got here?

What those books do not always say, but do imply, is that “we are all immigrants here.” That implication, no matter how inadvertent, has sometimes been used to defend or justify the dispossession and genocide of this land’s first inhabitants. It is also important to note that when it comes to ancient civilizations (Egypt, Phoenicia, Greece, China), the earliest records we have are typically four to five thousand years old. There weren’t even human beings anywhere in the British Isles twelve thousand years ago (the entire area was covered with ice). But there were Indians in the Americas then. No matter how one interprets the data, Native Americans are not immigrants. They are indigenous to the Americas.

What do Indians say about their origins?

There are Dakota people who know that Indians came from Spirit Lake. There are Hopi people who know that Indians emerged from the center of the earth in Arizona. There are Christians who know that the story printed in the Bible is an accurate description of humankind’s arrival in the world. Some of those Christians are Indian, including a Pueblo man who told me that Jesus Christ traveled North America two thousand years ago; he was just known by a different name in Pueblo country. It is important to realize how divergent some of the origin beliefs held by native people are, and it is also critical to know that the people who hold these beliefs, like all other people of faith, are firmly convinced of their truth—and they are as deserving of respect.

Although there are significant differences among the origin beliefs of different tribes, there are some commonalities, too. All North American tribal origin stories describe a spiritual creation of humans. Most detail the physical place where humans were put on earth by the Great Spirit, and that place is in North America, albeit different parts of the continent depending on which tribal tradition is being consulted.

Many people deny scientific assertions about evolution in favor of religious explanations. But in addition to the religion/science debate, Indians often resist the dismissal of their understandings of origin, which disregards not only their knowledge but also their wisdom-keepers, elders, spiritual leaders, and very ways of knowing.

Who else made it here before Columbus?

Seafaring Polynesians definitely made it to South America. The sweet potato, indigenous to the Americas, proliferated throughout Polynesia prior to Columbus’s trips to the Caribbean. Words from South American tribal languages traveled to Polynesia, and Polynesian peoples shared styles of watercraft with Indians in Chile. The Vikings also made it to maritime provinces in Canada about five hundred years before Columbus arrived in North America. Archaeological excavation offers evidence of their visits.

Did Native Americans scalp?

Yes. There has been some speculation that Europeans introduced scalping in North America as a form of bounty hunting. The lack of archaeological evidence of scalping prior to contact with Europeans suggests that it may not have happened in the Americas before their arrival. However, many historians do not accept this theory. If scalping originated in Europe, why was it primarily practiced in North America? Also, early seventeenth-century documents clearly show that scalping was an embedded custom when the French first entered the Great Lakes. Samuel de Champlain, for example, reported meeting the Algonquians at Tadoussac in 1603 when they were celebrating a victory over the Iroquois and dancing with about a hundred scalps. Many have argued that Europeans seized upon an older indigenous custom and transformed it into a bounty system during the French and Indian War and other conflicts as a way to encourage Indians to kill one another and to offer proof before being paid. Scalping was an entrenched native custom throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries.2

Scalp Dance, illustration by George Catlin, ca. 1844

Did Indians practice polygamy? Do they now?

Polygamy was a common practice among many tribes, a custom born of necessity. Men went off to war, traveled under dangerous conditions, went fishing on thin ice, and generally had much higher mortality rates than did women. Women had an immense work burden: raising crops, gathering and preserving foods, tanning hides, making clothing, and caring for small children. As a result, in many tribes men could have multiple wives, but women could have only one husband.

Although Native American polygamy evolved because of work and death dynamics rather than sexual power, the concept became culturally ingrained and the practice persisted long after the need for it had disappeared. It was more common for a man to marry two or three sisters rather than women from different families.3 Some leaders, like Ojibwe chief Hole in the Day, used marriage as a way to advance political aspirations, but this was the exception rather than the rule. When mortality rates shifted and missionaries began to gain traction in many tribal communities, the practice of polygamy was abandoned by most tribes. A few tribes in South America still practice polygamy. Observing the dating habits of native teenagers, some North American tribal elders joke that select young people didn’t get the message that the practice has ended.

What are native views about homosexuality?

Native American views on homosexuality are as varied and intense as those of the general population. Homophobia is just as rampant a problem in Indian country as it is anywhere else today. But the record shows that there was a respected and empowered place for homosexuals in historical Indian communities. The writings of George Catlin and Jesuit Relations are loaded with references to the respected and even exalted position held by homosexuals.

Gender identity can be very nuanced and complicated. But in many Indian communities, the most common variations of homosexuality were men who functioned as women in the traditional gendered division of labor and had male sexual partners, and women who functioned as men in all realms of the accepted gender role. The divisions of labor and social duty along gender lines usually left two primary groupings—male and female. A man who functioned as a woman in society usually adopted the customary clothing of women and performed the same duties and work as women. The same was true for women who wore the customary clothing and accepted the work and war duties traditionally reserved for men.

Today, the political and social fabric of Indian communities has changed dramatically. Gender is no longer a determining factor in political position for most tribes. Ceremonial life is the only realm that retains consistent vestigial reminders of the gendered division of labor. And in that realm there are still accepted transgender roles for homosexuals. Despite this history, mainstream media and social views probably have a greater impact on the perspectives of young native people today than the traditional values around gender roles or homosexuality. It is true that many Native Americans have a greater sensitivity to differential treatment based on race and gender and that Native Americans tend to vote for more Democrats than Republicans, which may indicate a somewhat more liberal modern political viewpoint among many, but certainly not all, native people.

George Catlin drew this rendition of a dance honoring a homosexual man while visiting the Sac and Fox Indians in the 1830s.

How was gender configured in native communities?

Each tribe had its own culture and customs around gender, and the degree of variance between customs was significant. For social, political, and ceremonial functions, many tribes had a very strictly gendered division of labor.4 Women and men each had specific duties and rights. They even wore different types of snowshoes.

Indian thinking about gender developed in ways dissimilar to European gender dynamics, where different duties often meant differential and unfair treatment of women. When asked why men and women sat on different sides of a ceremonial lodge, Mary Roberts, an elderly Ojibwe woman, explained that it was “to remind us that women and men each own half the lodge.”5 Usually, indigenous gender roles hinged on balance rather than equality. Often native women owned the home and had much greater power in marriage and divorce than did women in European societies. But not all tribal constructions of gender were beyond reproach. No culture should be romanticized or denigrated: like all others, Indians should be understood and evaluated on their own terms.

Do indigenous people in Canada get treated more fairly by their government than those in the United States?

Canadian Indians have not fared much better than their American relatives. Political and social developments for the indigenous populations of both countries have been parallel though not the same. The U.S. and Canadian governments both have attempted to undermine and diminish the status of tribal communities as sovereign nations. Both governments have actively participated in widespread efforts to assimilate the indigenous population. Native populations faced removal to reservations and had their children taken and sent to boarding schools. Widespread issues of substance abuse and an educational achievement gap plague native communities on both sides of the border.6

There are some differences. Canada is part of the British commonwealth of nations, and its independence was obtained through peaceful means rather than military revolution. For Canadian aboriginal people, this meant suffering through the colonial regimes of the French and British. Indigenous people in the United States had to suffer through—depending on the place—the colonial regimes of the Russian, Spanish, Dutch, French, British, and most importantly American governments. There were many ugly chapters in each of those colonial regimes, but some of the most intense physical violence was directed by the U.S. government and also state and local militias in the early American frontier age—the famous massacres often portrayed in movies.

Furthermore, the U.S. population is much larger than that of Canada, and 80 percent of Canadians live within fifty miles of the U.S. border. As a result, there are many parts of Canada where the indigenous population was and still is a majority. And many aboriginal communities in Canada are isolated, requiring a plane or boat for access. This relative degree of isolation has enabled some of these communities to maintain higher rates of fluency in their tribal languages and to rely more upon traditional lifeways such as hunting, fishing, and trapping to sustain themselves.

The British and Canadian governments have also differed from the United States in their legal configuration of tribal sovereignty. In the United States, the status of tribes as independent nations is verified and affirmed in treaty relationships and many court cases, leaving American Indians with a legally recognized and retained sovereignty. Canadian Indians have struggled to have their status as sovereign nations viewed as such or declared legally in provincial or federal courts. Ongoing efforts to affirm the sovereignty of First Nations in Canada have largely focused on political process and constitutional reform, creating another significant difference between the statuses of tribes in both countries.

It is not the case that Canadian Indians have fared better. There are differences in the two histories. The most essential features that define Indians as distinct groups of people and unique communities or nations—language, cultural practice, and belief—are threatened in both places. Many tribes, such as the Blackfeet and Ojibwe, have tribal communities on both sides of the border. Common geography, unifying cultural movements such as the powwow, and similar struggles serve to unify indigenous people in both places despite the differences in their histories.

What is the real story of Columbus?

The story of Christopher Columbus is one of the best known in our collective history but also one of the most misunderstood and misrepresented in our history books. I will try to separate fact from fiction and provide a different perspective on this deservedly famous figure in history.

In order to discuss the importance of Columbus in Indian history, we first have to lay out some of the background information in European history. In 1492, Spain had a long-standing trade feud with Portugal, and Portugal was winning. In 1486, the Portuguese Bartolomeu Diaz had rounded the Cape of Good Hope. Previously, the only way any European dared travel to India or China was through the Mediterranean and Middle East. In the Mediterranean were numerous pirates and middlemen whose activities raised prices on trade goods. Once Portuguese traders figured out how to get to Asia by going around the southern end of Africa, they could bring their goods to market at far less expense.

As was customary, the first European country to embark on a certain trade route or arrive in a certain “primitive” place claimed possession of that place, that route, and all human inhabitants of the “new” lands. The Portuguese laid claim to traveling around the south end of Africa. By 1498, now several years after Columbus’s first trip to the Americas, Vasco da Gama made it all the way to India via Africa, and the route was exclusively Portuguese. At this time, France and England’s navies were both quite weak compared to those of Spain and Portugal.

Spain was also running out of money, the result of staging an inquisition from 1480 to 1492. The depleted Spanish treasury had a big impact on Columbus and on Indians. In addition, Spain had been busy conquering Muslim towns in southern Spain. Much of Spain had been colonized by powerful nations from northern Africa between 711 and 718. However, by 1492, Spain had finally vanquished its foes and united the Iberian Peninsula. Columbus was funded by the Spanish monarchy not because they believed in him or his mission so much as because the small investment they made was worth the risk just in case Columbus was successful.

Christopher Columbus, as he is known by the Latin spelling of his name, was actually born Cristoforo Columbo, the son of a middle-class Genoese weaver, and became one of the most important figures in modern history. Although it is widely believed that Columbus was a genius for figuring out that the world was round, this information was common knowledge for all educated Europeans of the day. Sophisticated understanding of latitude had been developed by Eratosthenes in the year 300 BC. Eratosthenes also made the first estimate of the circumference of the globe and was accurate to within 2 percent of the correct measure. Sophisticated knowledge of longitude was developed by Ptolemy in the year ad 280. By the year ad 1000, most educated Europeans knew the earth was a sphere.

When Columbus beseeched the Spanish monarchy to fund his voyage, he did so with a boldness that surprises us still today. Even though Columbus was born a common man from Italy, he asked to become a Spanish noble. He also ambitiously requested one-tenth of the gold that was brought back on any trade route he might discover for the Spanish. Amazingly, both of those requests were granted.

He was also very lucky. The Portuguese and the Spanish staged voyages from different locations. If Columbus had sailed for any country other than Spain, he would probably not have been successful. Spain began most of its exploratory expeditions in the Atlantic from the Canary Islands. This launching point enabled Columbus to avoid the westerly trade winds and make it to the Americas. And, while sailors were uncomfortable sailing without the sight of land for many days, there was not a near mutiny on Columbus’s first voyage.

Upon arriving in the Americas, Columbus made many important and interesting observations. All of his original journals, notes, and correspondence survive today in various archives throughout the world. We know a lot about what Columbus said, thought, and wrote. In his first letter to the Spanish monarchs after arriving in the “new world,” he wrote, “Should your Majesty command it all the inhabitants could be taken away to Castile, or made slaves of on the island. With 50 men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”7

Columbus first arrived in the Bahamas. He then traveled to Española, what the Spanish called the present-day island of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, where he spent most of his time during his first voyage. The Spanish estimated the indigenous population of Española to be around two million people. Tribal people there accepted the Spanish as visitors and friends. Communication without a mutually intelligible language must have been extremely difficult, and there were many misunderstandings, including an exchange between Columbus and the principal Taino chief, Guacanagari. Columbus gave the chief a red cape and the chief gave him a tiara. The chief saw this as a fair exchange to cement a friendly trade relationship, but Columbus interpreted the gesture as one of submission—that the chief was surrendering his kingdom to Spanish authorities.

One of Columbus’s three ships was damaged and had to be scuttled. As a result, when Columbus made preparations to return to Europe, he had to leave thirty-nine sailors behind. He brought with him small gold trinkets, food, and a few Indians. The Indians were captured in secret—they did not come willingly.

Upon returning to Spain, Columbus was received with incredible fanfare. He was granted all the primary requests made prior to his voyage. Columbus did not acquire large quantities of gold in the Americas. In fact, most of the gold he collected the Taino (Arawak) Indians had traded for with tribes from mainland Mexico. However, Columbus was sure to point out that there were vast quantities of gold to be had at Española. Columbus also asserted the availability of large quantities of resin, spices, and other valuable trade goods.

On Columbus’s second voyage to North America, Spain sent a military force, numerous scribes, and many other officials and subordinates. The Spanish were surprised when they arrived at Española. The thirty-nine sailors left behind had all been killed. From their writings it soon became clear what happened. Lacking food, provisions, or means of subsistence, they survived by the good graces of their Indian hosts. The Spaniards became increasingly belligerent and took numerous Indians as slaves, using them to obtain food, to provide shelter, and for purposes of sexual gratification. Eventually, the Indian hosts grew tired of their maltreatment by the small number of Spaniards on their island. Remember, there were over two million Indian inhabitants and only thirty-nine Spaniards. Unrelenting, the Spaniards were eventually killed by the Indians. The returning Spanish force, however, saw this history as one of unprovoked Indian aggression. An assault on Spanish men was an assault on the Spanish king: the Indians had to be punished.

The Spanish government at Española immediately instituted a new policy. All Indians were required to bring one hawk’s bell—about a quarter teaspoon—of gold dust to the Spanish four times every year. Chiefs were required to bring ten times that amount. This demand could not be met, however, because there were no large, readily available supplies of gold on Española. Most of the gold items in the Indians’ possession were obtained from other tribes in trade from the Mexican mainland. Very soon the available gold supplies at Española were exhausted. For failing to meet the gold dust tribute, Indians had their hands chopped off by Spanish authorities—literally tens of thousands of Indians were killed this way. The Spanish immediately sent their army into the field to round up renegades and punish those who attempted to escape Spanish authority. The cruelties inflicted upon native people were so severe that many committed suicide by drinking cassava poison rather than submit to maltreatment at the hands of the Spanish.

Bartolomé de las Casas, a Jesuit priest and later bishop in the Catholic Church, accompanied Columbus on his second voyage and wrote several books about his observations in the “new world.” In one of those books he wrote, “The Spanish are treating the Indians not as beasts, for beasts are treated properly at times, but like the excrement in a public square … Columbus was at the beginning of the ill usage inflicted upon them.”8 Las Casas went on to write,

The Spaniards made bets as to who would split a man in two, or cut off his head at one blow; or they opened up his bowels. They tore babies from their mother’s breast by their feet and dashed their heads against the rocks. They speared the bodies of other babes, together with their mothers and all who were before them, on their swords … They hanged Indians, and by thirteens, in honor and reverence for our Redeemer and the 12 apostles, and, with fire, they burned the Indians alive … I saw all the above things … All these did my own eyes witness.9

Why does getting the Columbus story right matter?

I have always been amazed that we know so much about Columbus but say so little about the dark side of his story. Columbus kept copious notes and numerous journals. Las Casas wrote several books on the subject. Those books were based on his firsthand observations of what happened during Columbus’s voyages to the Americas. In spite of all we know, the version of events that we often teach our children is markedly different from what actually happened. This is starting to change: there are more and more revisions to ongoing curriculum and better resources available to those who teach it. However, we still have a long way to go to remedy the divergence between fact and mythology around Columbus. We have a long way to go in education. And we have an even longer way to go in educating our society and changing our politics around the subject. Columbus is seen by most as a hero. There are more places named after Christopher Columbus in the United States of America than anyone else in history except for George Washington. And no wonder he is mythologized as a hero, given what we are teaching our children.

This image is from a curriculum developed by Lifetime Learning Systems, Inc., and employed in the Milwaukee Public Schools system in the 1990s.

This drawing was rendered by Theodore de Bry (1528–98) to accompany the English printing of las Casas’s work In Defense of the Indians.

Grade school curricula often shows an Indian welcoming Columbus and Columbus ready to hug the Indian, with the caption, “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” And frequently the words celebrate and new world are emphasized in this narrative. How can you discover a place when there are already people there? Obviously, Columbus did not discover America. It was a new world to Spaniards, but it was not a new world to Indians. It’s now also clear that Polynesian people and Vikings also made it here long before Columbus.

But let’s be fair. Columbus’s mission established sustained permanent contact and communication between the Americas and the rest of the world. Neither the Vikings nor the Polynesians accomplished that. It was the culture of Spain and the rest of Europe during that time to make claims of discovery and possession. Columbus was, after all, a man of his times.

But consider this line of thinking. As I traveled in Europe some years ago, I wanted to see concentration camps. Outside the town of Munich, Germany, I looked for Dachau. However, there were no road signs until I was only one kilometer away. It seemed like the Germans were hiding that camp, like they were ashamed of it. I then went to Austria, and I looked for Mauthausen concentration camp. I found it, but there, too, I only found road signs about two kilometers away. Austria had joined Germany with the Anschluss and had culpability in the Final Solution—they had something to be ashamed of, too. But if you go to Auschwitz in Poland, you will see signs 200 kilometers away, 150 kilometers away, 100 kilometers away, 50, 25, 10. You can’t miss it. It’s like they were saying, “Look what the Nazis did to us.”

All human beings have dark chapters in their personal histories. And all nations have dark chapters in their histories. Guilt is not a positive emotion. And looking at this history is not intended to make anyone feel guilty. However, it is important for all countries and all individuals to examine dark chapters in order to learn from them and prevent them from reoccurring. The Germans had to mandate instruction about the Holocaust in grades K–12. They had to make formal apologies for the culpability of the German people in the Nazis’ Final Solution. And the German government had to make reparations to Holocaust survivors. These steps and actions in no way made up for everything that happened during the Holocaust. However, they did make it possible to have a conversation about healing and to help mitigate the chance of a holocaust ever happening again in Germany.

Here in the United States, very little effort has been made to voice formal apologies, make reparations, or pass political mandates about education.10 Yet this country was founded in part by genocidal policies directed at Native Americans and the enslavement of black people. Both of those things are morally repugnant. Still, I love my country. In fact, it is because I love my country that I want to make sure that the mistakes of our past, our dark chapters, do not get repeated. We cannot afford to sugarcoat the dark chapters of our history, as we have for decades upon decades. It is time for that to stop.

In 1992, on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage, we had an opportunity to set the record straight and to strive for healing. We know a lot about Columbus. The stories were not hiding; people were hiding the stories. But in 1992, instead of saying, “Let’s make the next 500 years different,” the U.S. government simply established the Quincentenary Jubilee Commission. It is hard for many people to see how much damage is done by pretending there were no ugly chapters in American history.

Then-president George Bush, Sr., received a first-class education in the United States. However, no American president has written his own speeches since Abraham Lincoln. Each has a staff of smart and educated people with a huge amount of resources to craft policy and speech. Bush and his staff could have done so much better. Some of the words that jumped out at me from his statement on Columbus include greatest achievements, discovery, milestone, great navigator, determination, Christopher Columbus Quincentenary Jubilee Commission, commemoration, opened the door to a new world, set an example for us all. Yes, his example was followed, but it is not one I would like my children to emulate.

Like Christopher Columbus, George Bush, Sr., was a man of his times. However, it is important that we do not give our leaders a pass. We have enough information and resources to get this story right. We do not have to sugarcoat our history. On the contrary, we owe it to those who died and suffered to tell the truth, and we owe it to future generations not to lie to them. When teaching high schoolers, it is easy to look at the writings of someone like las Casas and talk about different perspectives on Columbus. At many schools, Columbus is put on trial and students argue both cases—that he was a man of his times and needs to be understood as such, and that his actions were unforgivable. No matter the conclusions, this activity certainly provides a more well-rounded discussion and understanding of Columbus.

I am also well aware that teaching grade schoolers is a different matter. However, there is still no need to glorify what for many people is a day of mourning. Native Americans changed the world with the introduction of many different types of food, medicine, obsidian scalpels still used in modern surgery today—all kinds of things—and the rest of the world changed Indians, and some of those changes were positive. Examining these gifts is a better entry point for discussion of this part of the historical narrative than glorifying the beginning of a colonial regime that killed millions. And make no mistake about it—there is glorification of this conquest.

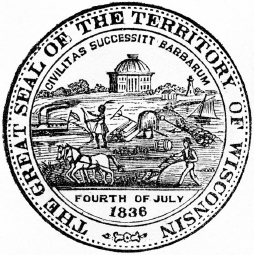

Depicted on the great seal for the Territory of Wisconsin is an image of an Indian facing west, apparently boarding a steamship. The natives of that state, the Ho-Chunk, or Winnebago, were subjected to nine separate removal orders. Some were forcibly relocated from the region by being boarded onto steamships and sent to Santee, Nebraska. On the seal is also a white farmer industriously plowing up the land, plus the emergence of the state capitol building in the background. And the Latin caption says it all: “Civilization Succeeds Barbarism.” There is no way to interpret this seal other than as a glorification of the forcible removal of Indian people from Wisconsin and the land being turned over to whites.11 We sugarcoat our history, which enables us to celebrate even the ugliest chapters. We need to think real hard about why we do that and what message it sends to our children.

The great seal of the Territory of Wisconsin

There are some great resources available for teachers. Rethinking Columbus, by Rethinking Schools, is a practical guide for developing a curriculum. Whether you are teaching kindergartners or high schoolers, there is something here for you. Units about the Columbian Exchange—the transfer of ideas, technologies, and raw materials between Indians and the rest of the world—are a great entry point for younger kids. Appropriate for middle schoolers or high schoolers are more substantive discussions of Columbus and the resource material for teaching about him. I also recommend Columbus: His Enterprise by Hans Koning, which synthesizes much of the available research and writing on Columbus in an easy, user-friendly format.

What is the real story of Thanksgiving?

There are parts of the Wampanoag-Puritan relationship that have been correctly incorporated into the Thanksgiving narrative. But there are many dimensions to Puritan-Indian relations that have been greatly embellished and exaggerated.

Chief Massasoit of the Wampanoag forged a peaceful relationship with the Puritans. A Patuxet Indian named Tisquantum, or Squanto, who had briefly been a captive in England, lived with the Wampanoag in the early 1600s when this relationship developed. Massasoit, Squanto, and many Wampanoag did teach the Puritans how to farm corn, beans, and squash, rotate crops, maintain soil fertility, and survive in the harsh New England climate. So this first part of the Thanksgiving myth bears some truth.

However, there is no evidence of a tribal-white harvest celebration during the first Puritan winter in America in 1621. Although the Wampanoag, Pequot, and other Indians in the region routinely celebrated their fall harvest, the first evidence of a white-tribal harvest celebration appears in 1637. Also, it is an obvious romanticization to assume that the Indian-white relationship was all peace, hugs, and good eating. Metacom, also known as King Philip, was one of Massasoit’s sons. In 1675, a chain of events led to a massive conflict sometimes called King Philip’s War. Around 5 percent of the white population and 40 percent of the native population in the region was killed. Metacom’s wife and children were sold as slaves in the West Indies, and the chief himself was killed by the Puritans. His head was placed on a pike and displayed in the village of Plymouth for more than twenty years.

The real Thanksgiving—it was complicated. Thanksgiving wasn’t established as a holiday until the Civil War era and didn’t become a formal federal holiday until 1941.

What is the real story of Pocahontas?

Soon after the establishment of Jamestown in 1607, Captain John Smith was captured by Opechancanough, the half brother of Wahunsenacawh (principal chief of the Powhatan Confederacy).12 Wahunsenacawh’s daughter, Pocahontas, helped Smith escape. Smith wrote about his captivity in 1608, 1612, and 1624, but only his last account mentioned that he was going to be executed before Pocahontas intervened, a clear embellishment.

In 1609, Captain John Ratcliffe demanded food tribute from the Powhatan, and when they resisted, he waged a sustained war against them from 1610 to 1614. Pocahontas was captured by the English in 1614 and ransomed to her father. The chief agreed to peace for her return, but the English continued to hold her and manipulate him. Pocahontas, still a teenager, was baptized and married to English planter John Rolfe (not John Smith), in spite of the fact that she was already married to a Powhatan man. Though she was never free to choose her relationship, she still wrestled with divided loyalties. She went to England with Rolfe, where her beauty brought her a great deal of attention, but she died, at age twenty-two, before she could return to America. Her son, Thomas Rolfe, survived and settled in Virginia, where some of his proven descendants still live today.

When did the U.S. government stop making treaties with Indians and why?

The United States established the right to make treaties in its earliest official configuration and codified that right in the U.S. constitution. The new country wanted to assert its sovereignty as it strove to become legitimate in the eyes of others. In both the constitution and early American history, treaties with Indians were the same as treaties with any other nation. But in 1871, a power struggle between the House and the Senate terminated the legislative power of the United States to treat with Indian nations.13 Simply put, the House appropriated funds for Indian affairs but had no say in treaty making, while the Senate ratified treaties but did not hold the purse strings. When the Senate refused to engage both legislative houses in the treaty process, the House terminated the right to treat with tribes.

At this point, Indian treaties started to be handled differently from those made with other nations. New treaties to create incentives for removal could no longer be made. Congressional acts and executive orders—which were occasionally negotiated—sought to serve this function in the following decades. It seems counterintuitive that the United States would stop making treaties with Indians when there were still vast stretches of territory that had never been ceded, including more than three million acres around Upper and Lower Red Lakes in Minnesota alone. But there were many ways to get land from Indians, and the U.S. government made abundant use of these alternatives.

Why do some people use the word genocide in discussing the treatment of Indians?

The dictionary defines genocide as “the systematic killing of all the people from a national, ethnic, or religious group, or an attempt to do this.”14 The legal definition of genocide developed by the United Nations in 1948 is “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”15 The reason that some people use the word genocide in discussing the treatment of Indians is that every single part of the dictionary and legal definitions of the word can be used to describe the historical treatment of Indians.

France attempted genocide on the Fox Indians in the 1730s, even refusing to allow women and children to surrender and issuing an official genocidal edict to back up their actions. During the French and Indian War, the British sent blankets infested with smallpox to tribes opposed to their colonization of the Great Lakes. Commander Lord Jeffrey Amherst instructed his subordinates to “inocculate the Indians by means of Blanketts, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race”; a recent outbreak had made blankets available, and by the next spring, tribes in the area were suffering from the disease.16 The Russian, Spanish, and American colonial regimes all engaged in genocide toward the indigenous peoples of the Americas. In the United States, attempts to eradicate entire tribes had the greatest success in California, but other genocidal efforts were carried out across the country against the Apache, Lakota, and numerous other native nations. After the Dakota War of 1862, the tribal population in southern Minnesota was systematically hunted down, harried, relocated, and disrupted to the point where the state was almost completely depopulated of Dakota Indians. The present Dakota communities there have never fully recovered.

Even more recently, Indians have endured policies that fit the legal description of genocide, including the residential boarding school programs of the United States and Canada, the systematic removal of Indian children from their homes via social service practices, the ongoing wanton disregard for conditions of extreme poverty and homelessness in parts of Indian country, and the involuntary sterilization of Indian women by the U.S. Department of Health. (The U.S. government sterilized twenty-five thousand Indian women by tubal ligation without their consent in the 1960s and 1970s.17) Genocide might be the most honest word we have to describe these events.