“Indian time means that we will do your ceremony until it’s done. That’s not an excuse to be late or lazy.”

THOMAS STILLDAY, Red Lake (Minnesota)

Why do Indians have long hair?

There are around five hundred distinct Indian tribes in North America, and their cultural beliefs are diverse. For many Native Americans, hair was viewed as a symbol of spiritual health and strength. Leonard Moose, an Ojibwe elder from Mille Lacs, said that hair was like medicine and if someone’s hair was cut, his or her medicine would leak out. Moose claimed that when he was a child, if someone had a haircut, the parents would usually use a hot rock to cauterize the wound on the child’s hair and prevent his or her medicine from draining away. Hair was a manifestation of spiritual strength or power but also a visible symbol of that power, and thus a source of pride and even vanity. All of these elements combine to provide a distinct cultural perspective about hair.

For most Indians, hair was only cut under certain circumstances. Meskwaki and Mohawk warriors plucked hair on the sides of the head, a developing tradition in wars where scalping was commonly practiced. Many Diné, or Navajo, cut children’s hair on their first birthday and then do not cut it again. They believe that the purity of childhood preserves spiritual strength and that the haircut will enable greater development of that strength as the child grows. Among some tribes, hair was cut as part of tribal mourning customs, but this practice was not universal. You can imagine how it must have felt for many native children to have their hair cut against their will upon entrance into U.S. government–run boarding schools (see page 138). Today, there are still many Native Americans who wear their hair long and carry the cultural belief that the hair is a symbol of spiritual strength.

Do Indians live in teepees?

Not usually. Europeans do not usually live in straw huts or ride horses as their primary means of transportation. And Indians do not usually live in historic dwellings or travel by foot, dogsled, or horse. Questions like these often speak to the mythologized fascination with Plains Indians, as seen in Dances with Wolves and other movies. We cannot hold onto a stereotype of how any people are and use that as the barometer for their authenticity.

Native Americans are diverse, and each group’s practices have changed over time, but that does not diminish their authenticity. Today at sun dances, powwows, and other events, members of some Plains tribes set up tepees. The Iroquois use a longhouse for ceremonial functions. Many tribes in the Great Lakes use wigwams for ceremonies. In parts of the Southwest, hogans and pueblos are used for both ceremonial and everyday shelter.

What is fasting and why do Indians do it?

A fast is a search for a vision that will establish a relationship between the faster and the spiritual world. Many Indians believe the Great Spirit has a plan for everybody, and one never knows what it is, but fasting is a place where one can get a glimpse of it. By giving up food and water, the person who is fasting becomes disconnected from the physical world and more strongly connected to the spiritual world. This enhanced state enables a faster to be approached and “pitied” by spirits with the gift of a song, a medicine, the right to give Indian names, or the company of a guiding spirit.

For many tribes, a woman’s power is her birthright, represented by her ability to bring life into the world through pregnancy and childbirth, and manifests when she comes of age. A man’s spiritual power has to be earned through fasting. Males or females can fast any time of the year, but typically boys and young men are encouraged to fast, usually in the spring.

The process customarily begins by giving tobacco to someone who knows about fasting. That person will provide instructions on how to prepare and when to go. Young people are often given a choice about fasting. For some tribes, that choice might occur when a parent or namesake offers a child charcoal in one hand and breakfast or candy in the other. Children who choose the food are not ready. When they choose the charcoal, they are ready.

There are many differences in the methods of preparation and fasting. Some people might use a sweat lodge. Some fast on a platform, some on the ground, some in a lodge or in a tree. Occasionally people will fast with others, but usually it’s a solitary activity.

It is possible to fast at any time of the year, but spring, a time of new life, is especially strong. Medicines are sprouting, birds and animals are coming back from migration or out of hibernation. Physically and spiritually, the world is coming alive. It’s possible to fast at any age, but fasts are most common in the spring of one’s life, when it is easier to earn pity from the spirits. Adults have to sit out longer to make the same connections.

What are clans and do all Indians have them?

Clans, or totems, are birds, animals, fish, or spiritual beings or places that represent different families in many native communities. Most tribes have clan systems. At Cochiti Pueblo there are two essential groupings—Turquoise and Pumpkin. Those groupings matter a great deal for the organization of some dances but do not function like the clan systems of other tribes. Many, including the Plains tribes, have maintained sophisticated kin networks without clan systems. Others, like the Dakota, used to maintain clan systems and kinship networks but have since lost and discontinued this practice. For most of the tribes in the Algonquian and Iroquoian language families, clans remain a critical part of tribal life. In Iroquoian tribes, tribal members follow their mother’s clan. The clan system is even incorporated into the rights of tribal members to participate in ceremonial longhouse doings. Ojibwe people follow the clan of their fathers. Forest County Potawatomi boys follow the clan of the father and girls follow the clan of the mother.1

For tribes that maintain beliefs in clan, it is customarily taboo to marry someone of the same clan. There are ingrained cultural concepts that vary from tribe to tribe for handling situations where one has a nonnative parent from whom they would normally receive their clan. Some believe there is an automatic adoption into a certain clan or a necessary ceremony or ritual to obtain a clan for the person who needs one.

Where are the real Indians?

Once, when I was lecturing in France, a man in the back of the room raised his hand with great excitement. French guys never get excited at academic talks, so I took his question. And his question was, “Where are the real Indians?” I suppose he was looking for someone who just stepped off the set for Dances with Wolves. I replied, “Where are the real Indians? Where are the real Frenchmen? There is a castle across the street, and there is nobody living in it. In fact, I don’t see anybody riding up and down the street on horses with shining armor. I don’t even see guys with berets and little pipes. Where are the real Frenchmen?”

All cultures change over time. What it meant to be French a thousand years ago, a hundred years ago, and today are all different. But a Frenchman can still be French even if he’s traveling in China because he carries that identity inside of him. It’s the same for Indians, who carry their identity with them. Many different things inform identity, including heredity, connection to tribal communities, traditional lifeways, and tribal languages. Each of those dimensions of identity might be threatened for many Indian people, but what it means to be Indian is both complicated and very real, in spite of the presuppositions engendered by movies and stereotypes.

What does traditional mean?

That’s a loaded question. Defining tradition is a very subjective process. People from Pittsburgh who happen to be of German heritage might have a very different idea of what is traditional compared to the Pennsylvania Amish. Tradition is about much more than biology. Because cultures, languages, technologies, and values shift far faster than most people realize, it is hard to define what is truly traditional.

For Indians, defining what is traditional gets further tied up in a sometimes-contested discussion of identity. For example, the community of Ponemah on the Red Lake Reservation in Minnesota has 100 percent traditional Ojibwe religious belief and funerary practice. No one has ever been baptized in that community. And the fluency rate in the tribal language there is the highest of all Ojibwe communities in the United States. Across the lake, in the community of Red Lake, on the same reservation, the tribal population is predominantly Catholic. People in Ponemah define tradition by religion, traditional lifeways, and language. But people from Red Lake tend to emphasize heredity (blood), hunting and fishing, and reservation affiliation as more central dimensions of identity, Indianness, and tradition.

This example demonstrates how contested political discussions of tradition can be. Personally, I find the customs, practices, language, and beliefs of my ancestors to be defining features of tradition and central to my identity. But I also live in a modern world. I drive a car and wear manufactured clothing. Although my life differs from those of my ancestors of a few hundred years ago, I find much more in common with them in my own religious choices, cultural beliefs and practices, and language. I tried to make that distinction to the Frenchman who asked about where the real Indians were, but it is important to recognize that the tension between old and new, modern and traditional, is ongoing and intense in Indian country.

Aren’t all Indians traditional?

There is incredible diversity in Indian country. There are communities in Canada and remote parts of the Navajo reservation where fluency rates in native languages approach 100 percent. In many other communities, there are no speakers left. Some communities have 100 percent traditional religious and funerary belief. There are also some communities in which all members have converted to Christianity. Each place has its own history. And it is usually through no fault of their own that many Indians do not speak their tribal languages. At the same time, while many forces and realities are beyond the control of any individual human being or community, there are some things Indians can exercise more control over. And, fair or not, it is necessarily up to native people to take steps to stabilize traditional custom, practice, and language.

Billboard on the road to Ponemah (Red Lake Nation)

In the Upper Midwest, almost 30 percent of the nonnative population is of German heritage. But their families have lived in the United States for as long as five generations. They don’t speak the German language and have never lived in Germany. In fact, if you sent them to Germany, they might have a nice vacation, but they would be most comfortable when they came home to the United States. There is a difference between having German heritage and being a Deutschlander. And so too is there a big difference between having native heritage and being Apsáalooke, or Crow. I believe strongly in the importance of tribal language, although I’m not so much of a fundamentalist as to say that non-speakers are not Indian. But the more divorced Indians become from tribal language, culture, religion, and custom, the more unrecognizable we become to our ancestors. How much can a people change before they are no longer the same people?

Why is it called a “traditional Indian fry bread taco”?

That question is as befuddling to me as “Where do the wood ticks go during the wintertime?” There is a traditional fry bread taco stand at every single powwow and many other secular and social events. Frankly, the words traditional, Indian, fry bread, and taco do not have any business even being in the same sentence. Taco? Really? Fry bread was created by resourceful Indians who were trying to subsist upon U.S. government rations of lard and flour. It is certainly not traditional. Indians laugh at the irony, and I know I’m a sucker for one of those once in a while myself. But Indians need to wake up to the harsh realities of the world. Ironic and humorous though it might seem, given that we have the highest rate of diabetes for any racial group in the world, mislabeling this concoction as “traditional” is killing us.

What is Indian time?

“Indian time” is another terrible misconception widely held in Indian country. Today the concept is used as an excuse to be late or lazy. But Native Americans in former times were neither. If you woke up late or took a lazy day, your children often went hungry. People worked hard and were physically fit in order to survive. In former times, Indians also worried a great deal about “bad medicine” and had a level of fear and respect that modified behavior. People did not show up late for social or ceremonial events out of fear that doing so might offend someone who had the power to do spiritual harm to others.

Mille Lacs Ojibwe elder Melvin Eagle once told me that when he was a child, he and a friend were playing and laughing in a road and an old man walking by thought they were laughing at him. He told his mother, who immediately made him take tobacco and gifts to the old man’s residence to apologize and explain that he was not laughing at the old man. This care of relationships, like being on time, is a mark of respect. Today, among some people I see a lack of work ethic and respect that would have horrified any Indian from a couple hundred years ago. According to Red Lake Ojibwe elder Thomas Stillday, Indian time simply means that we will do your ceremony until your ceremony is done, no matter how long it takes, with no shortcuts.2 It is not an excuse to be late or lazy.

What are Indian cars?

Regardless of what may have happened in recent years, when we look back to BC (Before Casinos), most Native Americans shared the experience of impoverishment. The good and bad vestiges of that suffering permeate Indian communities today, even in places where poverty is less of a concern. The Indian car has been viewed by many as a symbolic manifestation of the shared experience of poverty. The Indian car is the one that is falling apart—its bumper is held on with duct tape and bailing wire, and the tires are all brothers from different marriages. I have a couple of cars in my yard that meet this description, but those vehicles are not defining features of who I am. And I make that distinction with purpose.

Today in Indian country, there is an incorrectly but widely held view that to suffer in poverty is to be authentically Indian. While poverty was a common experience, the negative dimensions of the culture of poverty are at odds with older, traditional indigenous views of self. Pictures taken in the nineteenth century show people wearing decent pants and beautiful beadwork. They took pride in their personal appearance. They dressed up, especially for ceremony. Now, many Indians dress down, wearing jeans and t-shirts and leaving their beadwork in the closet when it’s ceremony time, for fear they will be labeled as stuck-up or seen as showing off. While the native talent in artistry and beadwork is proudly on display at the modern powwow, it is absent from almost every other dimension of tribal life.

Ojibwe Indians at White Earth, 1886

People dress down and celebrate their poverty because they mistakenly view an expression of poverty as an expression of Indianness. Our ancestors traditionally sought to improve their standard of living through hard work and personal pride in trade, diplomacy, and trapping. Today’s embrace of the culture of poverty is at odds with the world view of our ancestors.

I thought that Indians have a strong sense of ecological stewardship, so why do I also see a lot of trash in some yards?

If we were all true to the religious and cultural principles of our forebears, there would be many fewer problems in the world. The Bible has a lot of teachings about peace, but many Christians actively participate in war and have done so consistently for two thousand years. It is true that many native value systems and religious beliefs espouse a deep respect for all animate and inanimate things. No matter how modest one’s dwelling might be, traditional belief systems emphasize keeping it clean and treating it with respect. Although the sense of environmental stewardship attributed to Indians is sometimes romanticized, there is an authentic value of respect and reciprocity in native interactions with the natural world.

At the same time, Indians, like all human beings, have sought to advance their position and make life easier for themselves, occasionally resulting in divergence between belief and practice. Pressures on Indian land and livelihoods and European demands for furs all contributed to an indigenous practice of harvesting beaver to extinction in some areas. Native Americans in the southern Great Lakes intentionally set forest fires to extend the range of the woodland buffalo eastward all the way to New Jersey. These actions created easier access to critical food supplies, and while they had a positive impact on the population of buffalo, they worked to the detriment of certain other flora and fauna. Controlled fires also created fire breaks to protect villages from wildfires (and forests from village cooking fires) and to enhance the productivity of certain crops such as blueberries. Changes in the Land by William Cronon and 1491 by Charles Mann do a great job of describing the ways that American Indians made their environments.

Trash bothers me, too, but the issue of trash in people’s yards speaks to a larger concern. There has been a systematic attempt to assimilate Native Americans, and the effects of assimilation, historical trauma, and poverty have served to erode traditional values of respect and pride in personal appearance and residence. Possessing fancy clothes, cars, houses, and other displays of wealth does not mean that one is more respected in Indian country. But in many native communities the traditional value and belief is that, no matter how humble or extravagant the dwelling, good spirits are attracted to clean places and bad spirits hide under clutter and garbage. When I see garbage in someone’s yard, I am more likely to view it as an indication of acculturation than the degree to which traditional Indian values are environmentally sensitive. For me, Indians who do not keep their homes or yards clean are out of touch with these ancient yet important traditional values.

I see this issue as a reflection of the deeper one of poverty in Indian country. All disproportionately poor subsections of the population have a similar issue. Those who do not own their homes take less pride in their residences. Many tribes manage their own garbage and recycling programs and coordinate youth activities to clean up their communities. Tribes are doing their best to address this issue. Cultural values lend great support to that effort. But there’s still plenty of work to do.

Do Indians have a stronger sense of community than non-Indians?

Definitely. For most Americans, living in this country has meant dislocating from motherland and mother tongue. An American can move from the East Coast to the West and shift from being a New Yorker to being a Californian. Identity has become malleable. Native Americans have a stronger tether and bond to community. Even most Native Americans who leave their home reservations to work in cities will frequently travel home for family and community functions. And regardless of personal religious choice, it is exceptionally rare for Indians to have a funeral outside of their home community, even if they’ve spent most of their life living off-reservation.

Some places have an especially strong sense of community. In Ponemah, on the Red Lake Reservation, no individuals own land. All land is held in federal trust for the benefit of all tribal members. Homesteads are established for families that live on the reservation, but those families cannot own the land on which they live. This situation makes it hard to get a loan for a house, but it has maintained a strong sense of community. The rights to homestead in a particular place are passed down through families. Almost all of the families on that reservation are living on plots of land that their parents and grandparents and great-grandparents, going back through generations, have lived on. Further, in Ponemah, the custom is to bury one’s dead relatives in the front yard. There are often many generations buried in every front yard—which makes it a lot harder to sell the family farm and move to California. And although not every single member of every single family attends every funeral, at least someone from every family attends local funerals and brings food. They do this not just because they knew the person, which, given a community numbering one thousand, they usually do. They do it simply because they are members of the same community. The Pueblos also have a remarkably strong sense of community. When there is a dance or feast day, every family participates without question or resistance.

What is Indian religion?

Because there is so much diversity in Indian country, there is no such thing as “Indian religion.” Customs and traditions vary significantly from tribe to tribe. In the Great Lakes and other regions, some tribes have societies that require a religious initiation. Such initiations are conducted entirely according to ancient tribal customs but function much like baptism and confirmation do for Christians. Those ceremonies serve to place the initiates on a particular religious path and are often accompanied by instructions and expectations for a certain code of conduct. Other tribes have societies that are spiritual in nature but do not serve to induct someone into a particular religious belief system. For most tribes, though, religious belief is less focused upon specific ceremonies or induction into specific groups than on a set of values, beliefs, and rituals that are infused into everyday life. As such, Indian religion, spiritual perspective, and custom tend to be organic, somewhat fluid, and integrated rather than exclusive.

Indian religious practices were forbidden by the federal government in 1883, and parts of those regulations were not formally repealed until 1978. Many Indians became Christians of various denominations, and others have adopted aspects of Christianity. An organization called the Native American Church incorporates traditional pre-Columbian use of peyote with Christianity. Other Indian religious rituals have infused ideas, values, or even customs of Christianity with tribal practice.

Why do Indians use tobacco for ceremonies?

Most tribal communities in North America use tobacco. Although customs vary from tribe to tribe, most Indians believe that any spiritual request made of the Creator or one’s fellow human beings must be “paid” for. Tobacco is viewed as an item of not just economic but primarily spiritual value. It is a reciprocal offering. Some tribes, including all of the Pueblos, also use cornmeal with this same view in mind.

Isaac Treuer offering tobacco

Some tribes, such as the Potawatomi and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), cultivate their own tobacco. Other tribes make “tobacco” from other plants and medicines, especially the inner bark of red willow or dogwood. Often red willow tobacco is mixed with other medicines or cultivated tobacco to form kinnickinnick. Indian people who practice traditional religious beliefs and customs differentiate between the use of spiritual tobacco and the abuse of chemical-laden pleasure tobacco. When tobacco is used in ceremony, generally it is the least carcinogenic form and the smoking does not involve inhalation, somewhat mitigating potential health risks.

It seems like Indians have a deeper spiritual connection than in many religious traditions. Is that true?

Most Indian religious traditions are far less hierarchical, structured, or driven by rigid organization than Judeo-Christian religious forms, making association and practice more fluid, natural, and easily obtained for practitioners. For example, Christians rely upon the Bible to acquire moral teachings and religious belief. Someone who is not baptized is often denied or at least discouraged from participating in communion.

For many participants in Indian spirituality, there is no dogmatic set of principles to govern their knowledge of the Creator. It is far more likely that someone would go fasting to obtain a vision and rely upon that vision for their deeper understanding of the Creator and their relationship with the Almighty. There is much less power placed in the hands of a native spiritual leader than in a pope, bishop, priest, or other religious official. Indian religious leaders do have status and often receive a high degree of respect from people in their community. But if somebody does not like what they hear or the substance of any particular religious form in Indian country, they are free to disassociate without significantly diminishing their access to their religion or their status as a religious person among their peers. The same freedom does not exist for Catholics, for example, who would have a hard time practicing their faith without attending mass.

Access to genuine spiritual connection can be a frustrating part of the human experience for all people, including Indians, especially those living in urban communities or places where traditional religious practice has become severely depleted or assimilated. Those frustrations are somewhat mitigated by the fact that for most Indians, prayer is not a weekly event arranged by others but a daily event that is self-orchestrated. Further, access to more complicated ceremonies and free expression at those ceremonies is less regimented for many native people.

What are some of the customs around pregnancy and childbirth?

Customs vary so much from tribe to tribe that it is difficult to give an answer that represents the breadth and depth of belief and practice. It is the prevailing belief of many Indian people that we do not have souls. Rather, we are souls. We have bodies. In fact, our bodies are but temporary houses for our souls. The terms soul and spirit are used interchangeably. The Ojibwe word for body, niiyaw, literally means “my vessel.” The body is a container.

Many tribes believe that when a woman is pregnant, the spirit of her unborn child is hovering around her body. The fetus inside of her does not yet house the baby’s soul; the spirit of the child has not yet fully arrived. For this reason, there are many taboos when a woman is pregnant.

Another commonly held belief in the Great Lakes region is that the spirit of the child actually chooses his or her parents. That spirit then comes to earth to hover around his or her mother while she’s carrying the fetus, the body that he or she will inhabit upon birth. This belief is often strongly impressed upon young people as they themselves become parents, showing them the Indian way of thinking about their spiritual responsibility.

Many Native Americans believe the Great Spirit has a plan for everyone. The Great Spirit’s plan has a profound impact and influence on everyone’s life. We never know what the Great Spirit’s plan is, but we can get glimpses of it through dreams and visions while sleeping or fasting. At the same time, there are also forces of random luck both good and bad. Sometimes people die before their time. Sometimes people live beyond their time. The world is not fair. But it is our belief that when we follow the teachings of our ancestors and tread upon the earth with respect, we have a greater chance of seeing the Great Spirit’s plan realized. Traditional elders often admonish their relatives not to interfere with the Great Spirit’s plan. This is one of the reasons why something like murder is not accepted in many tribal cultures. We do not know better than the Great Spirit when someone’s time should end. Many Indians choose not to have abortions because of this common belief.

In former times, there was a much higher rate of infant mortality. Because a small baby’s hold on life is tenuous, many customs seek to show the spirits that the family is grateful for the arrival of their new child but does not assume that a gift is given before it comes. For example, people in Indian country usually do not have a baby shower before the child is born; doing so would show the spirits that the family assumes the child will arrive and live. Such assumptions are not only out of keeping with traditional teachings; they can also lead to incredible grief should there be misfortune with the pregnancy or childbirth. In keeping with this view, Earl Otchingwanigan (Michigan) and other elders have often said that the cradleboard for a family’s firstborn should not be made until the child is four weeks old. Once the cradleboard has been made, it becomes a family heirloom, and it can be passed from the first to the second to the third child without any fear of negative consequences or assumptions.

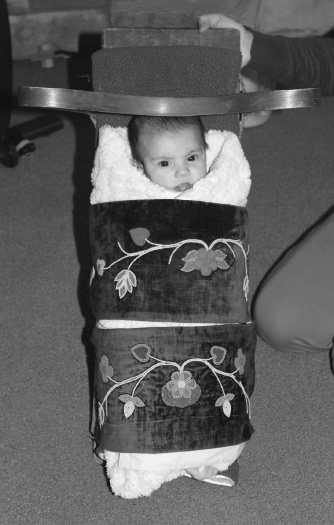

Luella Treuer in a cradleboard, January 2012. The cradleboard entertains an infant while keeping the child safe.

It is widely believed that when a woman is pregnant, the hovering spirit of the baby is very vulnerable. Expectant mothers are told to be careful of what they say, as it can invite good or bad luck. In some tribes, mothers are told not to look at salamanders, snakes, or even cats. Many families instruct expectant mothers not to eat burnt food. Everything an expectant mother consumes affects her baby, including well-known things, such as drugs or alcohol, but also traditional foods. Too many strawberries or blueberries might give the child blue or red marks on his or her body.

Expectant mothers in many tribes are also urged not to attend funerals. The spiritual process for the arrival of her child is the exact opposite of that for the departure of someone who passed away. The two don’t mix. Everybody loves a brand-new baby—even departing souls love brand-new babies. Out of fear that the departing soul at a funeral might want to take a sweet baby with him or her, expectant mothers simply stay away. Even young children are usually kept away from funerals. If a child’s presence at a funeral cannot be avoided, the custom for many tribes is to rub charcoal on his or her forehead. This is a “passover,” so the departing soul will not see or disturb the child. It is believed that failing to mark a passover could cause bad dreams for the child or possibly invite the child’s own departure from the earth.

There is a great deal of variation in regional customs around childbirth. According to Ojibwe spiritual leader Archie Mosay (Wisconsin), the parents made a tea out of catnip, called name-washk in Ojibwe, in order to give the new baby his or her first bath. This plant grows abundantly throughout the region, is picked in the summer, and can be dried. Once the tea is made, the liquid is strained. Some families also lay the baby on a bed of moss. It is believed that in so doing the child will be bonded with Mother Earth.

Many native families save the placenta and bring it home. There are a few different customs around proper treatment of the placenta. According to Ojibwe elder Leonard Moose, the placenta should be put up in the east side of a white pine tree. The white pine is a symbol of wisdom and longevity, and east is the direction from which the sun, the source of all life, rises. According to Ojibwe elder Earl Otchingwanigan, the placenta should be buried on the north side of a maple tree. The maple tree is the tree of life, and north is the direction at the end of the cycle. With all of these customs, tobacco is put out with the placenta.

A week or two after the umbilical cord has been cut, the dried end of the cord falls off of the baby, and it is often placed in a small pouch. If the child is being kept in a cradleboard much of the time, the pouch is hung on the crash bar for the cradleboard. If the child spends more time in an Indian swing, the pouch is tied onto the swing. If the child uses neither a cradleboard nor a swing, the pouch can be hung on the wall near where he or she sleeps. After one year, the spiritual connection between the baby and his or her umbilical cord fades. It can be kept as a memento, but the cord serves no physical or spiritual function. It is said that babies who did not have their cord and belly button saved for a year will spend the rest of their lives “looking for it.” They might want to open cupboards in strangers’ houses or look through other people’s medicine cabinets. It is believed that this habit is derived from the denial of connection to one’s belly button. We become emotionally attached to anything that we see or touch extensively, as in the umbilical cord in the womb. The attachment a child has to his or her cord simply fades over time.

What are naming ceremonies?

Obtaining an Indian name is one of the most basic yet treasured customs in Indian country. Traditions vary from tribe to tribe, but there are some commonalities as well. Indian names are given in tribal languages, with very few exceptions. Many tribal members believe these are the languages of the spirits, who give the names through people. For many tribes, including the Ho-Chunk, Meskwaki, Dakota, Lakota, and others, there is an ancestral connection in the giving of a name. Parents do not usually pick the name for their child; rather, the parents pick a spiritual leader to bestow a name upon their child. For tribes where the ancestral connection is critical, the giving of a name creates a strong and lifelong relationship between the person receiving it and an ancestor who has gone on to the spirit world.

Other tribes, such as the Ojibwe, do not usually have an ancestor connection in the giving of a name. For them, names come from spirits, not from people. Those who officiate at naming ceremonies are more like translators. Name givers speak to the spirits and the people. They translate. The names are usually obtained from fasting or dreams, and each name has a story behind it. Someone might see a vision or have a dream about a giant bear descending through the clouds and give the name “Bear.” Some Ojibwe chiefs have used public names, in addition to their spirit names, that suited their purposes. Bagone-giizhig (Hole in the Day) and some other Minnesota Ojibwe chiefs even used their fathers’ names to capitalize on their recognition and prestige.

Many Ojibwe tribal elders instruct people to have a feast four days after the birth of a child. The purpose of this first feast is to welcome the arrival of a new spirit in the world. In some places, the naming ceremony is performed at this feast. For others, it happens later. Both parents have equal say about choosing a name giver. The only requirement for name givers in most tribal traditions is that they have an Indian name themselves.

However, no matter who is running a naming ceremony, some ideas about traditional Indian names are universal. Indian names are spiritual identification—how spirits know people. The Ojibwe word for body, niiyaw, literally means “my vessel.” The body is a container. This word is reflected in other Ojibwe words, like niiyawe’enh, meaning “my namesake,” a term used interchangeably for both the name giver and the name receiver because the meaning describes the way a name giver puts part of himself into his young namesake and the namesake’s body becomes a housing for part of the name giver’s spirit. The namesake relationship is for life. But a namesake is more than just the person who gives a name. A namesake acts as an adviser, guide, and role model, much like a godparent in other traditions. Namesakes are important in other ceremonies throughout life.

Usually, if someone wants to ask for spiritual help, he or she must personally approach a wise person and give tobacco. But when namesakes take tobacco, they are making a lifetime commitment. Later in life, someone can call his or her namesake and ask for spiritual help, even if the namesake has moved far away. Because namesakes accept tobacco on the day of the naming, they can smoke their pipes and pray for their namesakes.

Can a nonnative person get an Indian name?

In many tribal customs, Indian names can be bestowed upon anyone, regardless of race. The custom is open and widely shared. However, this practice is not universal among all tribal communities. For some, names come from specific ancestors and cannot be given to someone who is not a lineal descendant. For others, names come from ancestors and can go to anyone, but family members are reluctant to give such a special personal honor to an outsider. Some tribes, like the Hopi and Pueblo, used to be more open to outsiders but got overrun by curiosity seekers; they have made many of their cultural displays and practices more exclusive to protect their sanctity and to ease access for their own people.

If a non-Indian person wishes to obtain an Indian name, he or she should simply offer tobacco to a knowledgeable spiritual leader and ask what the custom is in that area. And should the answer be that Indian names are only given to Indian people in that community, he or she should respect the existing traditions.

What are coming-of-age ceremonies?

As in many cultures, adolescence is a special and empowering time in a person’s life. Customs vary from one tribe to another and are also usually very different for boys and girls.

In Indian country, menstruation is universally seen as a representation of the spiritual power of women and their ability to bring life into the world. This view is quite different from common cultural beliefs in mainstream society that often leave adolescent girls feeling dirty or embarrassed when their change of life occurs. For many tribes, a woman’s spiritual power in relation to other spiritual powers is similar to the repelling effect of trying to push together two magnets: it’s not bad, but it needs to be given its own space.

When a girl gets her first “moon,” she is infused with this positive spiritual power. It is a common belief that the power is so great that it could interfere with other beings, other processes that are in the world. In former times throughout the Great Lakes area, when a girl got her first moon, she was sequestered in her own wigwam. It’s difficult to do that today, so tribal members who follow traditional customs make accommodations. A girl might spend more time in her bedroom or another safe, private place. In times past, this separation was enforced in a very strict way—young women were secluded from men, from sacred items, and from many kinds of ceremonies. During this time, grandmothers and female namesakes gave her instructions on how to conduct herself as a woman.

Most Great Lakes tribes instruct girls to use their own dish and spoon every time they get their period for the year after first menses. Some use this dish and spoon throughout the first year. This practice teaches about how powerful they are and how to use restraint, how to be aware of their actions. Most girls store their special dishes in a bundle separate from other household items. Other commonly followed rules for the entire first year as a woman include: don’t go swimming, don’t go in the water, don’t step over anything, don’t handle men’s belongings, don’t touch anything growing—new life, brand-new babies, or puppies.

This is the start of the time when a girl can have a baby. She is instructed about the physical changes to her body and her rights and responsibilities as a woman. During her first year, an Ojibwe girl can’t eat traditional foods until a feast is held where someone feeds her that season’s food as it is harvested. The feast offers protection to the harvests: the woman’s power is so great that if she eats the fresh wild rice, or blueberries, or fish without a feast she could affect the crop in that area.

Once the final food is fed to an Ojibwe girl at the end of her first year as a woman, there is a more elaborate ceremony during which all the women, including her extended family and her female namesakes, come to give teachings. These lessons might include

* * * * *

You are a woman now. So, if you see a bunch of us sitting around, you come sit with us. You are one of us.

You are a woman now, so you have a right and a responsibility to be respected by men. What that means is

No one can hit you;

No one can call you names;

No one can make you do something sexually that you don’t want to do.

Look around at your ceremonies. You’ll see that there are jobs for women and for men. There is a place for women at ceremonies. Those places at those ceremonies show that balance of men and women.

If something cannot avoid being touched, you can use gloves to alleviate the possibility of your power interfering with the spirit power of anything else.

Cedar is a powerful medicine. It can be used as a smudge, as a tea, to sit on, in your shoes, even in your underwear. It acts as a barrier.

Refrain from most ceremonies. Stay back as far as possible. Exceptions are sometimes made for the most important and longest ceremonies, with added cautions.

Use your skirt. It is your spiritual identification as a woman. You should be proud of your womanhood. Just as cedar provides a barrier, if something is going to drop, your skirt provides that barrier and channels it down to the ground.

You will be cautioned to watch your skirt to make sure it doesn’t go over people or food.

After the first year is up, you don’t have to eat on separate dishes anymore, but your spiritual power remains tremendous every time you have your moon.

* * * * *

Sometimes this training is misunderstood by those outside the cultural practice as an assertion of uncleanliness for menstruating women. But the indoctrination of girls into the ranks of womanhood is accompanied by such strong and consistent reinforcements of positive power, right, and responsibility that the perception and practice in Indian country is one of empowerment.

Boys often receive instructions on their transition to manhood as part of a private experience while fasting soon after their voice begins to change. However, the transition to manhood in many tribal customs can also be associated with the assumption of responsibilities as a provider for the people by hunting, fishing, trapping, and snaring.

In most tribes, both boys and girls can harvest wild game. A person’s first successful hunt is usually a time of ceremony marking the transition to adulthood. The Ojibwe call the ceremony oshki-nitaagewin. Boys may be groomed a little more for it, but girls do oshki-nitaagewin too. The word means “to make a kill for the first time,” and the ceremony may be repeated for the first rabbit, fish, partridge, and deer.

When one first kills an animal, there is almost always an offering of tobacco. The hunter will actually speak to the animal killed. An effort is made to show the animal that he wasn’t simply killed for sport. The animal has given up his life so that the people can eat, a self-sacrifice. It is usually taboo to waste one’s kill. There are regional variations, but many animals have a part that is considered special, that houses the animal’s spirit. This part will be put out with tobacco. Some families cook the whole deer and invite the entire village when someone makes a first kill. It is now more common for a family to make accommodations for modern life by cooking some of the deer and then packaging up the rest to give away.

At most first-kill feasts, tobacco is shared. The people smoke. Someone approaches the hunter and takes a spoon of meat and offers the first bite to him, saying his Indian name. But the hunter has to refuse the first bite. Some people will offer it four times, and on the fourth time he can eat.

Ojibwe elder Mary Roberts (Manitoba) instructed young people to say something on the first refusal of the offered food: “No, I’m thinking of the children who have no one to provide for them.” The food is returned to the pot, a new piece of meat is taken and offered, and the hunter refuses again, saying, “No, I’m thinking of elders who can’t get out into the woods to hunt for themselves.” The food is put back and a third spoonful is offered, and again he refuses: “No, I’m thinking of the people who came here today to support me.” When offered a fourth bite of the food, he can eat it. Then the hunter is told, “You just changed your life. You are now a provider for the people. And every time you kill an animal, these are the things you think about: children who have no one providing for them, elders who can’t feed themselves, your family, community, and supporters. And to reinforce this, you now have to give away your entire remaining kill. You are not hunting for glory. You are hunting for food and to provide for your family and community. It’s important that you have respect for your family and the animals.” The young hunter is then thanked with hugs and handshakes and formally acknowledged as having transitioned from dependent to provider.

How come everyone’s laughing at a traditional Indian funeral?

Not everyone is laughing. Grief is real and difficult for people of all cultures. But for many tribes, belief in the afterlife is deeply held. Unlike funerary customs for many Judeo-Christian traditions, a death does not provide an opportunity for a priest to preach at the bereaved so much as it provides the family an opportunity to share with the dead. Food, songs, prayers, and instructions on how to reach the spirit world are given to the deceased. The process is often long and complicated, but it heightens the sense of a departing soul’s arrival in the spirit world, respect for tradition, and celebration of a life lived and an even better destination for the departing soul. People grieve at traditional funerals, too, but the grief is mitigated by the spiritual process and ritual. Community and family support is usually very pronounced. In many native communities, all families, even those not of immediate relation, cook and bring food to wakes and funerals.

The Ojibwe bury their dead in shallow graves, put holes in the rough box and casket, and even add holes to the spirit house which is placed over the burial site, all to enable the soul to visit its body. But after four years all of this fades and the spirit house is allowed to disintegrate and return to earth. Since the spirit of the departed is believed to be emotionally attached to its vessel, this gives time for the attachment to dissipate.

Do they charge for participation in native ceremonies?

For the most part, only charlatans do that. Mille Lacs elder James Clark once told me, “If you give someone a dollar for a ceremony, the spirits will look at it and think that it’s a pretty small blanket.” Most ceremonies involve a ritual gift of tobacco. For more important ceremonies, there is usually a food offering and a cloth item such as a blanket. More elaborate ceremonies may involve other types of gifts, clothing, and sacred items.

Customs vary a lot from ceremony to ceremony and tribe to tribe, but money is a new physical item and cultural concept, so its use in ceremony is usually uncommon. There are some occasions, such as ceremonial drums, where members may give money in lieu of a homemade or store-purchased gift, but that is different from charging others for helping them. Sometimes spiritual leaders travel great distances at personal expense to assist others, and those seeking their help may give them gas money, but that is also different from charging a fee. Most tribal members view charging for ceremony as “bad form,” and some even consider it taboo.

What is a sweat lodge?

A sweat lodge is a small, dome-shaped frame made out of tree saplings that is covered with bark, mats, blankets, or canvas. Rocks are heated in a fire outside of the lodge and brought inside. Water is poured on the rocks similar to the function of a sauna. Many Indians use sweat lodges to pray and sometimes incorporate medicines for healing or use it as a purification ritual in preparation for fasting, Sun Dance, or other ceremonies. The sweat lodge ceremony is one of the most well-known and widely practiced Indian ceremonies today. As a result, there is a great deal of variation in practice.

Sometimes the ceremony has been copied or even abused by outsiders. In October 2009, a white man named James Arthur Ray charged money to nonnative people to participate in an “authentic Indian sweat lodge ceremony” in Sedona, Arizona. He had dozens of people packed into a small lodge and kept it too hot for too long. Three people died: Kirby Brown, James Shore, and Liz Neuman. Ray was convicted on three counts of negligent homicide.3 In this case it seems quite clear that the person running the ceremony was an irresponsible charlatan who preyed on the emotional and spiritual vulnerabilities of nonnative people fascinated with Indian spirituality. I see his actions as criminal and spiritually reprehensible. Sweat lodges are commonly used by true native spiritual leaders from many communities, but the physical experience never endangers human life when done responsibly and when the event is carried out with a true desire to help others rather than profit from their needs.

Do Indians still get persecuted for their religious beliefs?

Yes. In 1883, the U.S. commissioner of Indian Affairs created a “Code of Indian Offenses” that was used to persecute tribal religious practice.4 Until 1933, Circular 1665 instructed Indian agents to ban and break up tribal dances, religious ceremonies, and giveaways, even after Indians became U.S. citizens in 1924. The first amendment to the U.S. constitution was insufficient to provide for the religious freedom of Indians the way it did for Americans of other races. In 1978, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act sought to remedy that.

However, even today, free practice of religious custom is sometimes elusive. In 2008, Damien Bad Boy, an enrolled member and resident of the White Earth Reservation (Minnesota), was continually harassed by the city of Mahnomen, which claimed that his sweat lodge (located on his private property) violated city building codes, fire codes, and noise ordinances. Bad Boy pursued legal action and eventually settled a civil suit out of court. The city has never changed its laws or sought to negotiate with the tribe to allow for traditional sweat lodge use.

His case was not unique. An Indian in Tennessee had his sweat lodge destroyed by the local fire department several times in the 1980s. And many tribes and tribal members cannot access their own sacred sites or sacred items. Peyote use for tribes that incorporate it in ceremonies and for the more modern Native American Church remains a contentious and sometimes restricted practice. Native Americans in federal or state prisons are often only allowed access to Judeo-Christian religious leaders. Tobacco and traditional medicines are not allowed in prisons or most schools. Although conditions have certainly improved over the past century, there are many ways in which free practice of ancient custom remains difficult for Indians.