“So you want me to choose between going to powwows and being with you. Well, I made up my mind. Come here pretty darling, give me a kiss goodbye.”

OJIBWE SONG BY PIPESTONE SINGERS

What is a powwow?

The word powwow is actually derived from a term for spiritual leader in the Narragansett and Massachusett languages but was later misapplied to many types of ceremonial and secular events. Although Ojibwe drum ceremonies and traditional Dakota wacipi dances sometimes are referred to as powwows, today’s events are commonly secular, not ceremonial, and are widely practiced all over North America. They usually last anywhere from one to three days, and they are open to people of all tribes, genders, ages, and races. Powwows are primarily dance events, where people wear sometimes elaborate beadwork, feathers, and other regalia and dance to a wide array of songs performed by numerous drum groups, each comprised of anywhere from five to twenty singers. The powwow is a relatively new cultural form, although one of the most vibrant in all of Indian country.1

Many tribes from the Northern Plains and Great Lakes had different types of drum ceremonies and war dances at the time of first contact with Europeans. From these ceremonies evolved a more secular dance that often involved people from many different tribes. It used to be that each eagle feather worn by an Indian represented a deed done in battle—a kill, wound, or scalp—so wearing a feather bonnet, bustle, or dog soldier hat marked one as a fearsome warrior. Often, warriors and chiefs proudly displayed their feathers at treaty signings and diplomatic events, showing their military might, parading into the compounds of U.S. Army forts, for example. This custom evolved into the current grand entry, where Indians of all ages and genders parade into the dance arbor, although it is still veterans who lead. Styles of dance from the Omaha (grass dance), Dakota (war dance), Ojibwe (jingle dress), and other tribes were freely shared across tribal lines.

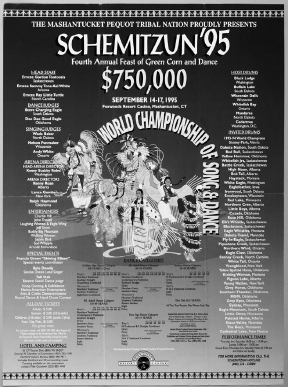

In the 1960s and 1970s, tribal governments in many places began to devote financial resources to support powwows, encouraging participation by providing meals and even money to dancers and singers. The custom grew into sometimes extravagant displays and even competitions with prize purses for best singing and dancing in multiple categories. Some of the wealthiest tribes, such as the Mashantucket Pequot, sponsored powwows with a total prize purse of more than $1 million. Even less well-off tribes like Leech Lake (Minnesota) have devoted hundreds of thousands of dollars to support powwow customs. The practice is vibrant because an overwhelming majority of the tribal population participates in powwows, and the custom transcends lines of religious choice, tribe, and even race. Access is easy, and the creativity of native artists and musicians finds fertile ground in the music and regalia.

Powwows also offer safe, sober environments that bring communities together and usually involve people of all ages, making them a healthy social option. Some tribal members feel that the financial support given to powwows is excessive and eclipses expenditures on other even more important initiatives such as tribal language and culture revitalization. As money motivates participation, some see powwows as part of the rapid cultural change engulfing Indian country. Even though powwow is positive by itself, many say it is not and could never be a substitute for older lifeways and customs.

Northern Wind Singers at Leech Lake Contest Powwow in Cass Lake, Minnesota, September 2009

What do the different styles of dance mean?

There are many different styles of dance. The “men’s traditional” style, which typically includes a feather bustle worn on the back and a feathered roach, dog soldier hat, or headdress, is one of the oldest and one of the most common. It is an evolution of older war regalia, where warriors earned feathers in battle and displayed them at war and scalp dances (but not always in battle). Today, it is not expected that those who wear such regalia have “earned” their feathers, although the feathers are still highly respected. Because in former times each feather represented a human being who was killed or wounded, a feather that is accidentally dropped in the powwow arena is usually picked up only by military veterans, who use a special song to dance around it and retrieve the fallen “comrade.” Traditional dancers mimic the actions of warriors and hunters scouting for enemies or game.

Another common men’s dance is the “grass dance.” Originally a distinct style used only in the Omaha Grass Dance Society, it spread to other tribes and became very popular in the 1970s and remains so today. Dancers do not usually have feather bustles, although they do often have head roaches made of porcupine and deer hair, sometimes with a feather or two. The body of the outfit includes aprons with long fringe that mimics the action of grass blowing in the wind. The dancers themselves spin, turn, and move their feet as if they were moving in tall grass, all to the beat of the drum.

Men’s traditional dancer

Men’s “fancy dance” is a derivation of the older traditional style. It incorporates many elements of traditional regalia, but usually with bright colors and double bustles that are not always made of eagle feathers. The dancers display rapid footwork and even gymnastic moves, spinning, cartwheeling, and jumping. Among the most popular styles to watch, it is much more widely practiced at competition powwows than traditional ones.

There are other styles of men’s dance as well, most of which involve mimicking the actions or motions of birds or animals. There are also many variations in styles of beadwork. The eastern Great Lakes often use more floral designs, while the western Great Lakes and Plains tribes often favor more geometric patterns, but dancers are free to create whatever they wish. Although some purchase their dance regalia, most make their own or have family members help them, incorporating personal colors acquired at their naming ceremonies, from dreams, or while fasting.

In older dance forms that predated powwows, women did not always dance or sing in all tribes. Today, women sing on powwow drums in Washington State and other places but are often forbidden or strongly discouraged from doing so in other parts of Indian country. The same is no longer true for dance. Powwow dancing is as popular and widely practiced among women as it is among men.

The “women’s traditional” dance has many variations in regalia. Southern Plains style often incorporate elk teeth as evidence of the hunting skill of a woman’s mate. Western tribes sometimes make use of the cowry shell, although that item has religious significance for many Great Lakes tribes and is less common there. Typically, the outfits incorporate elaborate beadwork and very long fringe, and gentle dance motions rock the fringe back and forth. Often, women’s traditional dancers ring the outside edge of the dance arbor in a circle around the men.

Men’s grass dancer

Men’s fancy dancer

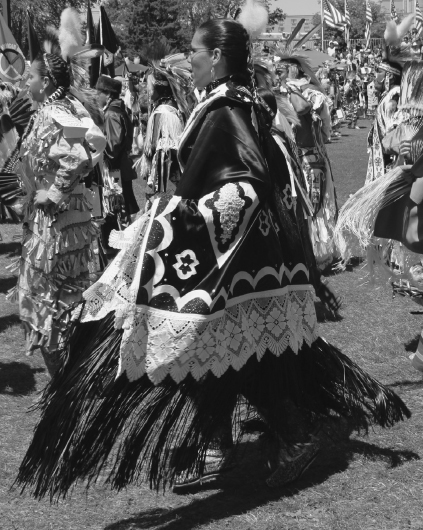

Women’s traditional dancers

Women’s jingle dress dancer

The women’s “jingle dress” style involves a long, tight dress covered in numerous jingles, often constructed from snuff can lids or other metal. The jingles make a swooshing sound. The jingle dress style evolved from an Ojibwe man’s dream of the dress around the time of World War I. The jingle part of the regalia was believed to have healing power. Sometimes jingle dress healing songs are performed at powwows, but usually the secular version of the dance is on display.

Women’s “fancy shawl” is the other popular form of female dance. The attire involves a colorful dress and shawl. The dancer spins and moves her arms to mimic the actions of a butterfly coming out of its cocoon and flitting about the arena.

Women’s fancy shawl dancer

Why are “49” songs sung in English?

The “49” song accompanies one of the few partner dances exhibited at powwows. The music is differentiated from other powwow songs by its slower and syncopated rhythm, to which partners hold hands and move in a long line, twisting and winding around the arena, following the moves of the lead couple. The music uses English in part because this dance is inspired by French and English partner dance customs but also because is it an especially popular form of music among young singers. Over time, it has sought to entertain with wit and even popular culture lines, such as “you got the right one, baby,” and “good ol’ fashioned Indian lovin.’” It’s part of the culture of the music.

How come they have a prize purse at powwows?

Not all Indians are happy about this development, although it is a huge part of the life of many native people. Competition for prize money in various styles of dance and singing derives from the rodeo component of powwow’s origins. As the dances became more rigidly stylized and secular and less ceremonial, this was an easy segue. Today, tribes with significant financial means often offer large prize purses to draw numerous singers, dancers, and spectators. It is seen as a way to show local hospitality, raise the profile of the host community in Indian country, and demonstrate authentic culture to outsiders.

Some Indians oppose the proliferation of contest powwows over traditional powwows and other cultural forms. They say that placing a monetary value on participants’ abilities to sing and dance supplants older cultural ideals of community cohesion, inclusiveness, and respectful generosity.

Powwow is the largest and fastest-growing part of Indian culture today. It is everywhere. Tribes like Leech Lake (Minnesota) spend over a hundred thousand dollars on prize money for Labor Day contest powwows alone; and Leech Lake has at least a dozen powwows a year, ranging in size from its large contest powwow to several smaller community powwows. The powwow budget for Leech Lake completely eclipses tribal expenditures on traditional culture and Ojibwe language revitalization, and that’s what really bothers some tribal members.

Tribes and tribal people are agents of their own cultural change. The modern powwow is a welcome, healthy gathering of people from many communities. It is a joyous social event and source of community pride. But it is not a substitution for traditional religion or ways of life.

Can white people dance at powwows?

Yes. Although there are prohibitions against the participation of outsiders in ceremonial events and customs for some tribes, powwow has no such official barriers. Furthermore, as the number of Indians with light complexions has grown over the past few decades, many nonnative people may even be assumed to be native at powwows. The powwow emcee will announce to the audience if there is a special honor song or exhibition song for a certain style of dance. Otherwise, powwow music is considered and often called intertribal—open to people of all tribes and races.

Schemitzun Powwow poster, Mashantucket Pequot, 1995

Do women sing at powwows?

Yes. Women from all tribes sing in a variety of secular and ceremonial functions, but there are rules and sometimes those rules are gendered. Some types of ceremonial music are exclusively male and other types exclusively female. For most Great Lakes tribes and many others, women do not touch ceremonial big drums or even powwow drums. Men sit around those drums and do the drumming and most of the singing, although women can and often do stand or sit behind the men, singing with them, usually an octave above to the same melody.

The first ceremonial drum that the Dakota gave to the Ojibwe came through the vision of a Dakota woman who “saw” men singing at the drum and women sitting behind the men, singing with them. That practice carried over to secular forms of singing on large drums for the Ojibwe, Menominee, Potawatomi, and others. For those tribes, it is not seen as an exclusion of women but rather as the greatest way to respect the vision of the woman who “gave birth to the drum.” Tribes in the Pacific Northwest do not have the same prohibitions, and women often sing on larger powwow drums there. But tribal people respect the traditions of the host communities, including their varying protocols for gender and singing.

What is the protocol for gifts at powwows?

Visitors are not required to give gifts at powwows, where it is the host community’s responsibility to show generosity to others. Toward the end of the powwow, the host community usually sponsors a giveaway, during which they make large piles of blankets and other goods and distribute them to dancers, helpers, and spectators. Sometimes a family will sponsor a giveaway. Once in a while, a family that is having a hard time might ask for a blanket dance to solicit donations for travel or health care. Contributing money during a blanket dance is a free will donation.