In complex environments, the successful expert is creating a “simulation” of the system in their head that is populated with information from many different sources. Somehow the diversity of information in their brain creates an emergent solution to the problem.

Norman Johnson1

We try to think about things that are important and knowable. There are important things that are not knowable… and there are things that are knowable but not important—and we don’t want to clutter up our minds with those.

Warren Buffett2

In choosing not to equip Berkshire Hathaway with a strategic plan, Warren Buffett has robbed himself of one of the essential instruments of leadership: a road map. Paradoxically, however, he remains firmly in charge of Berkshire Hathaway’s destiny, confident of meeting the target he has set for the company. That is because he has established a Circle of Competence within which he conducts his capital management.

Inside his Circle of Competence, Buffett understands the laws that apply in the allocation of capital. He is capable of qualifying opportunity. He is also able to pinpoint the origin of his mistakes so that he can amend his decision rules if need be. And it is Buffett’s Circle of Competence that gives him the sense of control that all humans crave in the face of uncertainty, and that most CEOs have “found” in the adoption of their more conventional strategic plans. Buffett reiterates:

We don’t have a master plan. Charlie and I don’t sit around and strategize or talk about the future of various industries or anything of that sort. It just doesn’t happen… We simply try to survey the whole financial field and look for things that we understand, where we think they have a durable competitive advantage, where we like the management and where the price is sensible.3

Buffett is renowned for the objectivity he brings to bear in the judgments with respect to comprehension, competitive advantage, management, and price to which he alludes above. He appears to conduct his analysis and proceed to action, or inaction, without emotion. However, while it is true that Buffett’s competitive edge in the management of capital does come from his objectivity, this is not achieved by being, in some hitherto unexplained way, emotionless. Emotions cannot, should not, be extracted from decision making. They are a necessary input to the process—especially important in the forward-looking, risky decisions at which Warren Buffett excels. It is only when they become too strong that they interfere with the capacity to make effective judgments.

As an allocator of capital—as a human—you have to have balance. Warren Buffett has that balance. Every decision he takes in the allocation of capital is taken from a position of utmost psychological security. His Circle of Competence is indispensable in this regard. But he has also put the groundwork in ahead of time to ensure that he is comfortable with the behavior suggested by managing capital within this circle and according to its dictates. It is Buffett’s emotional balance that, ultimately, gives him the objectivity that elevates and sustains his unusual approach to capital management above the average.

Thomas J. Watson Sr. of IBM followed the same rule: “I’m no genius,” he said. “I’m smart in spots—but I stay around those spots.”

Warren Buffett4

I’ve learned the perimeter of my circle of competence. If you name almost any big company in the US, I can tell you in five seconds whether or not it is within my circle of competence, and if it is I’ve probably got some sort of fix on it.

Warren Buffett5

Unique among allocators of capital, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger do not peer into the socioeconomic future when they make decisions on behalf of their shareholders. “We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts, which are an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen,” Buffett claims.6

Buffett and Munger do not believe that the economy lends itself to forecasting in the sense in which forecasting has come to be practiced. Just like the stock market in which he also allocates capital, the economy is a “complex adaptive system” that is poised in a critical state. One small change within the economy can either lead to a proportional outcome or ignite an avalanche of related effects that generate an outsized result. In the short and medium term, the direction and scale of events are therefore dictated by contingencies that cannot be determined.

In order to produce meaningful forecasts in such systems, says Per Bak, “one would have to measure everything everywhere with absolute accuracy, which is impossible. Then one would have to perform an accurate computation based on this information, which is equally impossible.”7

Warren Buffett concurs. He observes:

Years ago no one could have foreseen the huge expansion of the Vietnam War, wage and price controls, two oil shocks, the resignation of a president, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a one-day drop in the Dow of 508 points, or treasury bill yields fluctuating between 2.8% and 17.4%.8

Nevertheless, the admission of his own inability to predict these kinds of events has not prevented Buffett from rationally managing the capital at his disposal.9

In defining the boundaries of Berkshire Hathaway’s deployment of capital, Buffett refers to a representation of the universe that he carries in his head. This is a meta-model, a synthesis of the array of mental models that he brings to bear in his analysis of the world.

It is a model that does not go for completeness. It is a model that recognizes that some things that are knowable are not important. It also accepts that other things that are important are unknowable. It is a model that, to the exclusion of all else, focuses on the important and knowable.

Buffett prefers to make his capital allocation decisions within the realm of the important and knowable. This is his strike zone, if you will, where he is happy to swing his bat at the pitches thrown his way. It encapsulates a universe in which he can make an objective assessment of the opportunities presenting themselves to him, a universe in which the variables he considers in his decision making are so manifest that he can almost touch them, and where he is so sure of them that he can essentially eradicate uncertainty.

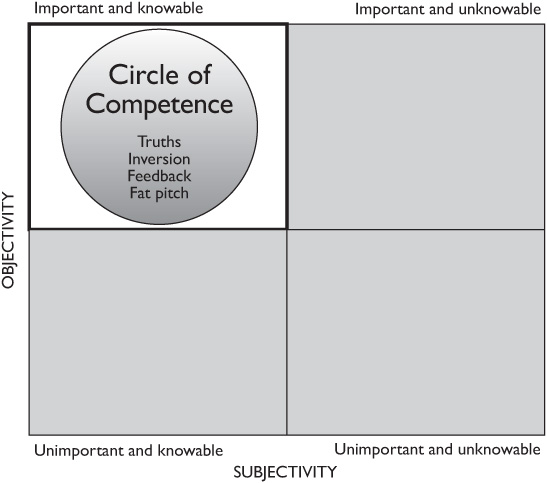

In order to administer this state of cognition, Buffett proscribes for himself the Circle of Competence shown in Figure 2. He draws this according to the following instructions:

1 He establishes what he knows by identifying truths, the dynamics that sit behind them, and their relationships to each other.

2 He ensures that he knows by a process of inversion whereby he seeks to disprove his prior conclusions.

3 He checks that he knows by seeking out feedback from the consequences of his decisions.

Our job really is to focus on things that we can know that make a difference. If something can’t make a difference or if we can’t know it, then we write it off.

Warren Buffett10

I look for what’s permanent, and what is not.

Warren Buffett11

Figure 2 The Circle of Competence

Warren Buffett says that he and Charlie Munger view themselves “as business analysts—not as market analysts, not as macroeconomic analysts, and not even as security analysts.”12

As such, when Buffett embarked on his investment career, he analyzed every company in the United States that had publicly traded securities. In effect, he started at A and worked his way through the alphabet. He says:

As you’re acquiring knowledge about industries in general and companies specifically, there isn’t anything like first doing some reading about them and then getting out and talking to competitors and customers and suppliers and past employees and current employees and whatever it may be. Virtually everything we’ve done has been by reading public reports and then maybe asking questions around and ascertaining trade positions and product strengths or something of that sort.13

Increasingly, as he conducted this research, Buffett developed the mental models that would allow him to create order out of what he was learning.

Thus, while he readily acknowledges that all businesses are subject to change over time, he has established that, in the realm of the business analyst, there exist incontrovertible truths that do apply and can be expected to hold in the long term, even in complex systems.14

Buffett found these truths in the laws of business economics: in the numbers game of capital intensity, in the capital requirements needed to maintain the status quo and those needed to grow the business, in the inevitability of the forces of mean reversion, and in the protection against these afforded by franchises, however these are defined.

He found them in the human proposition: in the hardwiring that governs the behavior of managers and determines the effectiveness of his and their leadership, and in the same hardwiring that governs the interaction between the firm and its customers, and managements and their shareholders.

He found them in the fundamental premise of value creation: that it is dependent on a manager’s ability to generate incremental earnings on capital “equal to, or above, those generally available to investors.”15

He found them in the equation for value: in which he incorporates a combination of business economics and the human proposition into a calculus that allows him to judge price.

And he found them in the essential characteristic of complex adaptive systems, which is that they will deliver opportunities to him: “The fact that people will be full of greed, fear, or folly is predictable. The sequence is not predictable,” says Buffett.16 Therefore, even though he doesn’t know when, where, or how opportunities will present themselves, he does know that “it’s almost certain there will be opportunities from time to time for Berkshire to do well within the circle we’ve staked out.”17

Buffett’s Circle of Competence surrounds those industries and companies in which he feels confident of being able to identify, comprehend and forecast the dynamics contained in his truths. Perhaps not surprisingly, he restricts this universe of the important and knowable to the simple. “The finding may seem unfair,” he says, “but in both business and investments it is usually far more profitable to simply stick with the easy and the obvious than it is to resolve the difficult.”18

Although Buffett will attest that his mental models have improved over time, the size of his Circle of Competence with regard to the businesses he feels capable of valuing has not changed since those early forays. That’s how immutable the laws of business economics are.

However, as befits the explosion of cognition that came later, Buffett has increasingly secured the perimeter of his Circle with regard to his understanding of the way in which human behavior shapes these fundamentals. These were the lessons that Buffett learnt when he transitioned from cigar butt investor to capital manager and, perforce, to leader. He confirms:

Charlie and I have learned a lot about a lot of businesses over 40 or 50 years. However, in terms of the new things that would come to us, we were probably about as good judges of ’em at the end of the second year as we would be today. But I think there’s a little plus to having [been around at it]—more in terms of human behavior and that sort of thing than knowing the specifics of a given business model.19

It is, of course, irritating that extra care in thinking is not all good but also introduces extra error… The best defense is that of the best physicists, who systematically criticize themselves to an extreme degree… as follows: The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you’re the easiest person to fool.

Charlie Munger20

There is a school of thought that humans accept all information they encounter as initially correct, and subsequently recode the information that is found to be false. Warren Buffett’s behavior suggests that he ascribes to this view.21

Buffett believes that transforming an area of knowledge into a Circle of Competence, and keeping it that way, can only be achieved if he constantly stress tests what he believes to be true. Charlie Munger, for instance, says that both he and Buffett “are very good at changing our prior conclusions.”22 The reason is that they are both in the habit of inverting their arguments. Says Charlie:

The mental habit of thinking backward forces objectivity. One of the ways you think a thing through backward is you take your initial assumption and say, Let’s try and disprove it.23

He continues:

For example, if you were hired by the World Bank to help India, it would be very helpful to determine the three best ways to increase man-years of misery in India—and, then, turn around and avoid those ways. So think it backward as well as forward. It’s a trick that works in algebra and it’s a trick that works in life. If you don’t, you’ll never be a really good thinker.24

Thus Buffett and Munger, two like-minded individuals who are inclined to agree on most things, overcome the potential that this has to damage their cognition by constantly trying to knock down their arguments, calling on the use of all of their mental models to do so. If the arguments still stand after they have been run through these—Buffett calls Munger “the abominable no-man”25—then they might, indeed, have some merit.

Part of what you must learn is how to handle mistakes and new facts that change the odds.

Charlie Munger26

The only way that Buffett can validate the decision rules originating within the Circle of Competence is to seek out, and take, feedback from them.

“Agonizing over errors is a mistake,” says Buffett. “But,” he adds “acknowledging them and analyzing them can be useful.”27 In keeping with this philosophy, Buffett conducts his post-decisional analysis, not on the ones he gets right (false positives will not provide him with the information he is looking for), but rather on the ones he gets wrong.

This is why Buffett is so ready to own up to his own mortality. He told his shareholders in 1986 in one of his regular confessionals:

As you can see, what I told you last year about our loss liabilities was far from true—and that makes three years in a row of error. If the physiological rules that applied to Pinocchio were to apply to me, my nose would now draw crowds.28

Buffett keeps a starkly honest internal scorecard of his own performance, in which he leaves his psyche nowhere to hide. Crucially, he counts against him the mistakes that most of us allow ourselves to get away with—his mistakes of omission:

What’s an error is when it’s something we understand and we stand there and stare at it and we don’t do anything. Conventional accounting, of course, does not pick those up at all. But they’re in our scorebook.29

And he considers the way in which his score is put together—flukes do not count.

In settings in which feedback on decisions is unambiguous and timely, such as in meteorology and games of bridge, practitioners have been found to develop a very good sense of their ability to judge relative to those who make decisions in settings in which feedback does not possess these characteristics.30 Buffett—who, not without coincidence, is an excellent bridge player—wants to calibrate his judgmental accuracy in the same way.

He wants to reduce the number of errors he makes. But, more importantly, he wants to be able to produce a forecast range in which he can be relatively certain that the outcome will lie. This is the essence of properly calibrated confidence. It illuminates why Buffett tells his shareholders:

I want to be able to explain my mistakes… If we are going to lose your money, we want to be able to get up there next year and explain how we did it.31

It also explains why Buffett reduces the ambiguity that can be contained in post-decisional feedback by being so honest with himself.

Having established the truths of his Circle of Competence, acquired the habit of inverting his arguments, and sought out feedback on the quality of the decision rules he is using, Buffett’s task in using this model in his management of Berkshire’s capital is to find value. The necessary tool that allows him to do this is, naturally, another incontrovertible truth: the equation for value.

The value of any stock, bond or business today is determined by the cash inflows and outflows—discounted at an appropriate interest rate—that can be estimated to occur during the remaining life of the asset.

Warren Buffett32

We just read the newspapers, think about a few of the big propositions, and go by our own sense of probabilities.

Warren Buffett33

Buffett tells us that the equation for value—described in the first quotation above—was set down nearly 70 years ago by John Burr Williams.34 With some manipulation of the terms used, Buffett deploys this equation in every sphere of his capital allocation at Berkshire:

It applies to outlays for farms, oil royalties, bonds, stocks, lottery tickets, and manufacturing plants. And neither the advent of the steam engine, the harnessing of electricity nor the creation of the automobile [will change] the formula one iota—nor will the Internet. Just insert the correct numbers, and you can rank the attractiveness of all possible uses of capital throughout the universe.35

There are two elements to this catch-all equation: (1) the forecast of future cash flows, and (2) the certainty attached to the production of that forecast cash flow, with the latter determining the rate at which the cash flows are discounted to present value. The greater the risk in an enterprise (for instance), the higher the discount rate that should be used in the equation, and the lower the value of the business for any given production of cash. You do not know a business if you cannot make judgments with respect to (1) and (2). Those that Buffett feels capable of judging define his Circle of Competence.

The risk facing any investor, says Buffett, is that the return on an investment does not protect his or her purchasing power against inflation, plus an opportunity cost that can be measured by the return the investor could have earned elsewhere. The same risk faces any allocator of capital and although, according to Buffett, this cannot be calculated “with engineering precision, it can in some cases be judged with a degree of accuracy that is useful.”36

With one very important exception, which I will delineate in Chapter 9, in pursuing this degree of accuracy Buffett is inexorably drawn to quantifiable, knowable ranges of odds, of the type that manifest themselves in the property casualty insurance industry in which he feels so comfortable setting prices. The universe of the important and the knowable cannot be that unless Buffett can specify the probabilities contained within it. What he looks for are stable frequencies.

A useful analogy in this regard is a game of poker.37 This is a complex process containing a range of possible outcomes, just like the operation of any business. In any particular hand, the probability of a particular combination of cards being a winning hand can only be imprecisely estimated. Yet at the same time, if thousands of hands are dealt, these “hidden” odds—the game’s stable frequencies—reveal themselves. They are knowable quantities.38

The way Buffett sees it, the same is true for companies that are impervious to material change. In those that make essentially the same pitch over and over again, stable frequencies will manifest themselves out of the complexity of the economy within which they operate. Not fixed odds, but a knowable range. Not an immutable range either, but a range in which change can be forecast.

From Buffett’s quoted investments, for instance, Coca-Cola and Gillette offer among the world’s best-known, market-dominant brands to people who wake up thirsty every morning and/or who need a shave. They place their affordable, easy-to-distribute products within arm’s reach of desire, and back this up with constant psychological reinforcement and conditioning through their advertising. Effectively, they play games where draws are always made from the same pack, where the rules remain unchanged, and where the chain of events is kept to a minimum. This allows Buffett to prune the decision tree of his forecast and attach odds that can be calculated with a meaningful degree of certainty.

Businesses such as these could more properly be described as a continuum rather than a branching tree. Buffett himself describes them as The Inevitables.39 He says:

Forecasters may differ a bit in their predictions of exactly how much soft drink or shaving-equipment business these companies will be doing in ten or twenty years. Nor is our talk of inevitability meant to play down the vital work that these companies must continue to carry out, in such areas as manufacturing, distribution, packaging and product innovation. In the end, however, no sensible observer… questions that Coke and Gillette will dominate their fields worldwide for an investment lifetime.40

Buffett’s other, wholly owned franchises present essentially the same fundamentals, albeit in weaker form. There are only a few companies in the world that Buffett feels comfortable describing as Inevitables.

“To the Inevitables in our portfolio, therefore,” he says, “we add a few Highly Probables,” by implication adjusting for the reduced certainty he has in forecasting the timing and quantity of their cash flows and judging the risk attached to these.

“Experience… indicates,” he adds, “that the best business returns are usually achieved by companies that are doing something quite similar today to what they were doing five or ten years ago.”41 In their own way, the Highly Probables—NFM, GEICO, Borsheim’s, Executive Jet, et al.—occupy the continuum that Buffett is looking for. “With the businesses we think about, I think that the moats that I see now seem as sustainable to me as the moats that I saw 30 years ago,” he says.42 Shielded from major change, drawing from the same deck sequentially through time, they throw off the knowable statistics that allow for the proper estimation of the important in the value equation. Their business economics do not present such a robust defense against reversion to the mean, but their human proposition does.

This is the objectivity that Buffett is seeking: business processes that generate statistical backgrounds allowing him to bring calibrated confidence to bear, to produce forecasts that can be made; a range of these that can be specified, containing risks that can be assessed. Thereafter, incorporating the yield on 10-year bonds (normalized for the business cycle), he discounts the weighted average of these forecasts back to a net present value. Then he waits.

We try to exert a Ted Williams kind of discipline. In his book The Science of Hitting, Ted explains that he carved the strike zone into 77 cells, each the size of a baseball. Swinging only at balls in his “best” cell, he knew, would allow him to bat .400; reaching for balls in his “worst” spot, the low outside corner of the strike zone, would reduce him to .230. In other words, waiting for the fat pitch would mean a trip to the Hall of Fame; swinging indiscriminately would mean a ticket to the minors.

Warren Buffett43

Be aware that Buffett runs the equation for value in his head. Charlie Munger says that he’s never actually seen Buffett perform a discounted valuation calculation. In essence, that’s how intelligible it should be.

Buffett has an Excel spreadsheet in his brain, which helps, but there should be so few variables in his equation and so little ambiguity that the math is simple.44 He is not looking for absolute precision. “It is better to be approximately right than precisely wrong,” he maintains.45 He has not reduced this to a numerical science. “Read Ben Graham and Phil Fisher, read annual reports and trade reports, but don’t do equations with Greek letters in them,” he says.46 It’s more a question of knowing the range of possible outcomes. When this is the case, the rest follows.

To Buffett, allocating capital to positive-net-present-value ventures in the strike zone is routine. Says Munger:

I’ve heard Warren say since very early in his life that the difference between a good business and a bad one is that a good business throws up one easy decision after another, whereas a bad one gives you horrible choices—decisions that are extremely hard to make. For example, it’s not hard for us to decide whether or not we want to open a See’s store in a new shopping center in California. It’s going to succeed.47

Indeed, Buffett says that economic goodwill at See’s “has grown, in an irregular but very substantial manner, for 78 years. And, if we run the business right, growth of that kind will probably continue for at least another 78 years.”48

Similarly, at GEICO, Buffett is content to let CEO Tony Nicely expand as he wishes, professing “there is no limit to what Berkshire is willing to invest in GEICO’s new-business activity.”49 The economics of this business are such the cost/value relationship of investing in it sits comfortably in the realm of Figure 2 where Buffett wants to allocate capital. Opportunities to do so are pitches at which Buffett is happy to let his operating managers swing.

However, as important as reinvesting in existing businesses is, the capital management decisions that have really counted at Berkshire Hathaway—the big ideas—have been far less routine. Buffett and Munger recognize that in those capital allocations of sufficient moment to shape the fortunes of an entire corporation, it is much too difficult to gain an edge by making hundreds of smarter-than-the-next-guy decisions. There just aren’t that many large-scale opportunities of value for which Buffett believes it is also possible to make a reliable judgment in respect of value. Comments Munger:

It’s not given to human beings to have such talent that they can just know everything about everything all the time. But it is given to human beings who work hard at it—who look and sift the world for a mispriced bet—that they can occasionally find one.50

“Therefore,” Buffett tells his shareholders, “we adopted a strategy that required our being smart—and not too smart at that—only a very few times.”51

Buffett and Munger differ on how many occasions they have been smart in their joint career—Buffett estimates around 25; Munger closer to 15—but, without being so, Berkshire’s performance would have been merely ordinary.52 Big ideas, such as the initial purchase of See’s and GEICO, are the fat pitches of Figure 2 that Buffett waits for. They should be so obviously in the strike zone that they are “no-brainers.”

“You know when you’ve got a big idea,” says Buffett. Fifty years ago, for instance, when he scanned Moody’s looking for cigar butts, the nobrainers would jump off the pages at him. When value was defined in relation to tangible assets, the tangibility that Buffett looks for was a given. “I’ve got half a dozen xeroxes from those reports… that I keep just because it was so obvious that they were incredible,” he says.53 Although Buffett has displaced the cigar butt equation with the more complex equation for value, his Circle of Competence still allows him to identify the pitch that he can hit to the bleachers.

Buffett knows that these pitches will be thrown every now and then. When they are, he enjoys a considerable advantage over baseball players like Ted Williams. “Unlike Ted,” observes Buffett, “we can’t be called out if we resist three pitches that are barely in the strike zone.”54

Buffett has no compulsion to act. “But,” he adds, “if we let all of today’s balls go by, there can be no assurance that the next ones we see will be more to our liking.”55 Equally, although Buffett is confident that, if he and Charlie were to deal with the evaluation of numerous fat pitches in a short space of time, their judgment would prove to be reasonably satisfactory, he also observes:

We do not get the chance to make 50 or even 5 such decisions in a single year. Even though our long-term results may turn out fine, in any given year we run a risk that we will look extraordinarily foolish.56

Herein lies the rub. The philosophy underpinning Buffett’s capital management, he says, “frequently leads us to unconventional behavior both in investments and general business management.”57

Buffett’s willingness to reject any opportunity when the equation for value does not add up can lead to long periods of torpor. His countervailing eagerness to bet when he knows the odds are with him, quite possibly in enormous size, also induces volatility in Berkshire’s results. In the short term, whether he’s passing up obvious home runs in, say, technology stocks or striking out in General Re, Buffett can quite easily look misguided.

At the same time, he is under no illusions as to the consequences of failing to spot, and connect with, the fat pitch: “If Charlie and I were to draw blanks for a few years in our capital-allocation endeavors, Berkshire’s rate of growth would slow significantly,” he notes.58 The pressure for more normal capital management (don’t just stand there, do something) means that Buffett can be called out by his shareholders if he simply shoulders his bat.

In the face of this intense pressure, he shrewdly observes:

Failing conventionally is the route to go. As a group, lemmings may have a rotten image, but no individual lemming has ever received a bad press.59

The condemnation that Buffett’s unconventional behavior invites, should it fail to produce the results expected to go with it, is suggestive of adverse imaginable outcomes. And this engenders a problem in terms of the accuracy of Buffett’s cognition and his objectivity.

When imaginable outcomes evoke strong emotions, human judgment normally becomes extremely insensitive to differences in probabilities.60 Buffett professes: “Charlie and I… like any proposition that makes compelling mathematical sense,” and he has premised his capital management on an ability to embrace any such proposition.61 If he were unable to cope with the emotional consequences of this approach and lose sight of the probabilities on which his analysis is based, the consequences would be disastrous.

[The] capacity to be made uncomfortable by the mere prospect of traumatic experiences, in advance of their actual occurrence, and to be motivated thereby to take realistic precautions against them, is unquestionably a tremendously important and useful psychological mechanism, and… probably accounts for many of man’s unique accomplishments. But it also accounts for some of his most conspicuous failures.

Joseph LeDoux62

I do only the things I understand.

Warren Buffett63

Experiments revealing the effect of strong emotions on decision making feature subjects who are given painful electric shocks of varying intensity, but with known probability.64 In the countdown period up to its delivery, their physiological responses to the impending shock (the chemistry of their emotions) is measured, and it is found that their emotional responses are correlated with their expectations about the intensity of the shock, not the probability of receiving it.

The reason for this is that we cannot weigh decisions without emotions. For much of the twentieth century the field of psychology denied this. It was dominated by the notion that “cold” cognition and emotion existed in isolation from each other and it was held that where the two did meet, emotions represented “an interruption to an otherwise logical (and preferred) mode of being.”65

Hitherto, it has been maintained that the objectivity that Warren Buffett brings to bear in his decision making can be explained by his ability to extract the emotion from the exercise. This cannot be true. In and of itself, pure cognition is incapable of triggering action. After analysis, we only proceed to action in the light of the affective, or emotional, responses that analysis elicits. We make decisions because their likely outcomes are perceived as good, bad, safe, risky-but-worth-it, smart, dumb-but-what-the-hell, because they feel right or wrong, and so on.66

These are the emotional markers that accompany every decision, the mobilization of a motivational state that precedes action. The capacities to plan cognitively, evaluate the merits and consequences of a decision, and construct imaginable outcomes are inseparable. People in whom the ability to generate anticipatory emotions has become impaired tend to be very poor at making forward-looking decisions. Frontal lobotomy patients, for example, who are unable to evoke emotional responses to unseen but imagined events, become confined to the present, are highly impulsive, and take unjustified risks. In games where they are faced with a choice of drawing cards from a high-risk deck that pays out handsomely but only sparingly, or a low-risk deck that pays out less but more frequently, they normally lose all their money very quickly. In spite of a strong desire to win and a thorough understanding of the game, they are incapable of experiencing the anxiety that should normally accompany risk taking. Thus, they consider the risky draws to be less risky than they are.67

If accurate judgments are to be made in the face of uncertainty, therefore, emotions cannot be removed from the process. However, in order to remain sensitive to the probability distributions contained in uncertainty and assess them reasonably, emotions do have to be kept in balance. Says Buffett:

Plenty of people have higher IQs, and plenty of people work more hours, but I am rational about things. But you have to be able to control yourself; you can’t let your emotions get in the way of your mind.68

Buffett’s Circle of Competence delivers a large part of his emotional balance. Within it he knows the knowable. In here, he is in control of the capital allocation process. More importantly in his Circle of Competence, he feels in control and, emotionally, this is very valuable. “Imagine the cost to us…” he tells his shareholders, “if we had let a fear of unknowns cause us to defer or alter the deployment of capital.”

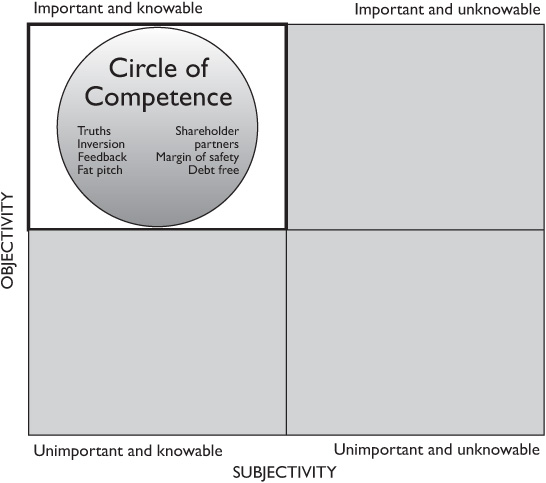

In order to be doubly sure that he retains this feeling of security, Buffett has also prepared the ground ahead of time. He perceives all of the imaginable outcomes of his unconventional behavior as benign: He has shareholders who are also his partners; he incorporates a margin of safety into every decision he takes; and, although Berkshire Hathaway does employ some debt on its balance sheet, from the point of view of this affecting Buffett’s willingness to be aggressive in his capital management, Berkshire is essentially debt free. It’s time to move on to Figure 3.

Eysenck proposed that highly anxious people attend preferentially to threat-related stimuli and interpret ambiguous stimuli and situations as threatening.

George F. Lowenstein69

I really like my life. I arranged my life and so that I can do what I want… I tap dance to work, and when I get there, I think I’m supposed to lie on my back and paint the ceiling.

Warren Buffett70

When Buffett set up his Partnership in 1956 he told those who backed him: “All I want to do is hand in a scorecard when I come off the golf course. I don’t want you following me around and watching me shank a three-iron on this hole and leave a putt short on the next.”71 That’s essentially the way in which he runs Berkshire Hathaway. Buffett wants to be the one who analyzes and puts right his mistakes, not his shareholders. For when people make decisions looking over their shoulders they become anxious and, in that state, are prone to concentrate more on the possible than the probable. In doing this, they tend to make decisions that can be most easily defended after the fact rather than those that are the most appropriate.72 This means that they gravitate toward the conventional. But the conventional is average and Warren Buffett does not want to be average.

Figure 3 Maintaining emotional balance in the strike zone

In managing Berkshire, Buffett treats even the smallest of its shareholders as equal owners in the enterprise. Therefore, if he is to feel comfortable in being unconventional, he has to have their mandate to do the unconventional. Crucially, and not without a design that will be delineated in the next chapter, Buffett is able to attest that “Berkshire probably ranks number one among large American corporations in the percentage of its shares held by owners with a long-term view.”73 These people understand Berkshire’s operations, approve of the policies of its chairman, share his expectations, and allow him to focus on the logical rather than the defensible.

“We are under no pressure to do anything dumb,” says Buffett. “If we do dumb things, it’s because we do dumb things. But it’s not because anybody’s making us do it.”74

Confronted with a challenge to distill the secret of sound investment into three words, we venture the motto Margin of Safety.

Benjamin Graham75

I still think those are the right three words.

Warren Buffett76

In the wake of the General Re acquisition, his biggest mistake to date comprising the largest and most unexpected loss in the history of the insurance industry, Buffett was still able to state: “We are as strong as any insurer in the world and our losses from the attack, though punishing to current earnings, are not significant in relation to Berkshire’s intrinsic business value.”77

By waiting for the premium over the intrinsic value of Berkshire’s stock price to expand in relation to the discount on General Re’s price, Buffett built a cushion into its purchase. He also maintained a cushion against adversity by adhering to underwriting standards in Berkshire Hathaway’s insurance businesses that guarantee its financial security in the face of occasional, exceptionally large losses.

“We had a margin of safety and it turned out we needed it,” Buffett told his shareholders in the wake of September 11. And he employs a margin of safety in every decision he makes, not just in the underwriting of risk or the subdivision of capital management that is investing, Graham’s preoccupation. Nor is Buffett’s current margin of safety principle the same as the one he used when he traded in cigar butts. The protection Buffett looks for between the price he can pay for a stock and its value used to reside in the discount it sold at in relation to the value of the assets on its balance sheet. Now that he buys and invests only in going concerns, this principle has morphed into an objective assessment of intrinsic value. That is, Buffett’s margin of safety is built into his equation for value—into his forecasts and their range—not brought into it after the fact. This explains why he is able to use the risk-free rate on long bonds as his discount rate.78 He doesn’t have to beef this up to incorporate risk, and this is an essential element of identifying the fat pitch.

Crucially, Buffett would not be able to calibrate his margin of safety if he allocated capital to enterprises that are subject to major variance. The introduction of change into the calculation would be analogous to the addition of new cards to the pack in a game of poker. If this were to happen, the previously identifiable probability distribution of possible outcomes on which Buffett relies would vanish—only to become apparent once more if we started the iteration process all over again. However, if sufficient new cards were added to the pack on a regular enough basis, the system would never settle down into one that would lend itself to forecasting in the way Buffett understands the term.

We will reject interesting opportunities rather than over-leverage our balance sheet. This conservatism has penalized our results but it is the only behavior that leaves us comfortable, considering our fiduciary obligations to policyholders, depositors, lenders and the many equity holders who have committed unusually large portions of their net worth to our care.

Warren Buffett79

Stress makes people suggestible.

Charlie Munger80

In conjunction with his margin of safety principle, Buffett also protects himself from anxiety by employing very little debt in his company. “You ought to conduct your affairs so that if the most extraordinary events happen, you’re still around to play the next day,” he says,81 and the concentration of his capital management into 15 to 25 big ideas precludes taking on the type of interest payments that most companies would consider appropriate. Many companies that take on debt that does not fit with their risk profile fail to show up for the next day’s game, not because their fundamental proposition is flawed, but because temporary cash flow problems cause them to default.

Accordingly, Buffett says:

We do not wish it to be only likely that we can meet our obligations; we wish that to be certain. Thus we adhere to policies—both in regard to debt and all other matters—that will allow us to achieve acceptable long-term results under extraordinarily adverse conditions, rather than optimal results under a normal range of conditions.82

This “restriction” has impeded Berkshire’s returns. Buffett told his shareholders in 1989:

In retrospect, it is clear that significantly higher, though still conventional, leverage ratios at Berkshire would have produced considerably better returns on equity than the 23.8% we have actually averaged. Even in 1965, perhaps we could have judged there to be a 99% probability that higher leverage would lead to nothing but good. Correspondingly, we might have seen only a 1% chance that some shock factor, external or internal, would cause a conventional debt ratio to produce a result falling somewhere between temporary anguish and default.83

However, in Buffett’s view he has made no mistake: “We wouldn’t have liked those 99:1 odds—and never will.”84

By chasing the additional return that extra leverage would afford, Buffett would also have had to take on what he describes as “a small chance of distress or disgrace.”85 By ensuring that he is free of this particular imaginable outcome, he grants himself the emotional security to consider swinging at fat pitches without fearing the consequence that he might mis-specify one or two of them as such.

If options aren’t a form of compensation, what are they? If compensation isn’t an expense, what is it? And, if expenses shouldn’t go into the calculation of earnings, where in the world should they go?

Warren Buffett86

References to EBITDA make us shudder—does management think the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?

Warren Buffett87

During the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century, a representation of the universe manifested itself that made sense of cause and effect for the first time in human history. It was a short step from there to the derivation of the forecasting techniques that would allow the calibration of risk and return and facilitate the advent of modern capitalism.88 The “light” in Enlightenment was switched on when intellectuals were able to utilize newly discovered laws of nature to create a simulation of the system in their heads, which was capable of explaining the mechanism that underpinned observable outcomes.

Warren Buffett’s Circle of Competence is such a system. The accuracy of his cognition has been similarly enhanced and his capital management enlightened.

Stan Lipsey, Buffett’s lieutenant at Buffalo Evening News, says that Buffett “can take a complex system and make it simple. I have sent a number of people who have business problems to Warren. They’ve traveled to Omaha; they’ve come back, and said, He just made it so simple.”89

Buffett’s Circle of Competence explains why. He has turned down the noise. He concentrates on the important and knowable. He knows these. Cause and effect are lit bright for him, infused with insights into human behavior that were not available to Renaissance man.

It is this state of enlightenment that grants Buffett—“the sage”—his unerring ability to puncture reality and dispel accepted wisdom on options and EBITDA, for example. It is this enlightenment that has allowed him to translate his Circle of Competence into the decision rules enabling him to act like an owner. In Part III of this book, we will delineate these and make them available to any CEO who would seek to emulate Buffett.